Abstract

CD10 has been demonstrated to be positive in endometrial stromal sarcoma (ESS) and thus is useful in establishing the diagnosis, but its expression in malignant müllerian mixed tumor (MMMT) and müllerian adenosarcoma remains to be clarified. In this study, 12 cases of MMMT (9 uterine, 2 tubal, and 1 metastatic), 6 cases of müllerian adenosarcoma (three corporeal, two cervical, and one tubal), and 7 cases of primary uterine sarcomas had their tissues examined immunohistochemically for expression of CD10, desmin, myoglobin, α-smooth muscle actin (SMA), and cytokeratin. Of the primary uterine sarcomas, two were primary rhabdomyosarcomas (one cervical and one corporeal), two were ESSs, two were high-grade leiomyosarcomas, and one was a high-grade endometrial sarcoma. Sarcomatous components in all cases of MMMT and müllerian adenosarcoma, as well as all uterine sarcomas, were positive for CD10, showing moderate to marked staining intensity with varying distribution except in one MMMT, which showed weak and very focal staining. In four MMMTs, three adenosarcomas, and one rhabdomyosarcoma, myoglobin- and/or desmin-positive rhabdomyoblastic cells were positive for CD10. The immunoreactivity for CD10 showed the same distribution for α-SMA and myoglobin in three and two MMMTs, respectively. In five cases of MMMT, carcinomatous components were focally positive for CD10, and in two cases small populations of round or short spindle cells in sarcomatous components were positive for CD10, α-SMA, and cytokeratin (CAM5.2). These results indicate that CD10 expression is not restricted to ESS but can be positive in MMMT and müllerian adenosarcoma as well as in a variety of uterine tumors including high-grade leiomyosarcoma and rhabdomyosarcoma. CD10 expression might be one of the characteristics of müllerian system-derived neoplastic mesenchymal cells.

Similar content being viewed by others

INTRODUCTION

CD10 or the common acute lymphoblastic lymphoma antigen (CALLA), a cell surface–neutral endopeptidase (NEP or EC 3.4.24.11) degrading various bioactive peptides, has been used as a diagnostic tool for precursor B-cell and T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia (1, 2), as well as Burkitt lymphoma (3) and follicular lymphoma (4). Recent studies have demonstrated that CD10 is expressed in a variety of nonhematopoietic tumors, including renal cell carcinoma (5, 6, 7, 8), transitional cell carcinoma (8), hepatocellular carcinoma (9, 10), gastric and colonic adenocarcinoma (11), prostatic adenocarcinoma (8), rhabdomyosarcomas (8), pancreatic adenocarcinomas (8), solid-pseudopapillary tumor of the pancreas (12), clear cell sarcoma of the kidney (13), glioma (14, 15 mediastinal germ cell tumors (16), schwannomas (8), malignant melanomas (8, 17), dermatofibroma (17), and dermatofibrosarcoma (17). In addition, CD10 is expressed on endometrial stromal cells (18, 19) and thus has been considered useful in making a diagnosis of endometrial stromal sarcoma (ESS; 8, 20, 21, 22, 23), which should be distinguished from cellular leiomyoma or leiomyosarcoma. However, CD10 expression in malignant müllerian mixed tumors (MMMTs) and müllerian adenosarcomas has remained to be clarified. Both of these tumors, which are considered to possess müllerian system-derived mesenchymal components, could pose potential diagnostic pitfalls, particularly when limited tissue sampling without epithelial components occurs. In this study, we examined MMMTs, adenosarcomas, low-grade ESSs, high-grade uterine leiomyosarcomas, primary uterine rhabdomyosarcomas, and high-grade endometrial sarcoma to demonstrate the utility and pitfall of CD10 paraffin immunohistochemistry, as well as to provide a better understanding of the phenotypic characteristics of müllerian-derived neoplastic mesenchymal cells.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Twelve cases of MMMT (9 uterine, 2 tubal, and 1 metastatic), 6 müllerian adenosarcoma (three corporeal, two cervical, and one tubal), and 7 cases of uterine sarcoma, were retrieved from the files of Kawasaki Medical School Hospital and Jikei University School of Medicine and from consultation files of two of the authors (Y.M. and T.K.). Of the uterine sarcomas, there were two low-grade ESSs, two high-grade leiomyosarcomas, two primary rhabdomyosarcomas (one cervical and one uterine), and one high-grade endometrial sarcoma. All hematoxylin and eosin (H&E)–stained slides were reviewed for confirmation of the diagnoses, and representative blocks were selected and submitted to immunohistochemistry. The antibodies, vendor sources, and working dilutions are listed in Table 1. Sections (4 μm thick) were cut from paraffin blocks of formalin-fixed tissues and were deparaffinized in xylene and rehydrated in graded alcohols. Immunohistochemical studies were performed using a streptavidin–biotin peroxidase complex method with standard protocols (DAKO, Glostrup, Denmark) for CD10, which was incubated with sections after treatment using a microwave antigen retrieval technique with 10 mm citrate buffer, pH 6.0, at high temperature for 5 minutes. Slides were stained with 3,3′-diaminobenzidine as chromogen. For other antibodies, the Envision system (DAKO) was employed without antigen retrieval. The immunostaining results were evaluated in semiquantitative fashion. The distribution of positive cells was expressed as focal (<10%), intermediate (10–50%), or extensive (>50%).

RESULTS

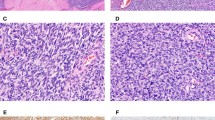

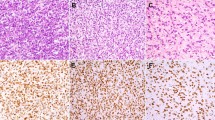

The sarcomatous components in all cases of MMMT (Figs. 1, 2, 3, 4), as well as müllerian adenosarcoma (Fig. 5) and primary rhabdomyosarcoma, were positive for CD10, showing moderate to marked staining intensity with intermediate to extensive distribution, except in one MMMT that showed only focal staining (Table 2). Two low-grade ESSs were diffusely positive with moderate to strong intensity, whereas high-grade endometrial sarcoma showed moderate intensity and intermediate distribution. In general, spindle and ovoid cells in MMMTs and adenosarcomas were positive regardless of the degree of cytologic atypia, showing a distinct cytoplasmic staining pattern (Fig. 2). In four MMMTs (Fig. 3), three adenosarcomas, and one rhabdomyosarcoma, myoglobin and/or desmin-positive rhabdomyoblastic cells with abundant eosinophilic and filamentous cytoplasm were positive for CD10. The immunoreactivity for CD10 showed a similar distribution for α-SMA and myoglobin in three and two MMMTs, respectively, but cells negative for α-SMA and myoglobin were also positive for CD10 in some areas. Chondroid and osteosarcomatous components were negative for CD10. In seven cases of MMMT, carcinomatous components, portions of serous or endometrioid adenocarcinoma, and areas showing squamous differentiation and some poorly differentiated solid carcinoma were focally positive for CD10 with cytoplasmic and/or membranous staining patterns (Fig. 4). Differentiation of carcinomatous components was not correlated with CD10 immunoreactivity. In two cases, small populations of round or short spindle cells in sarcomatous components were positive for CD10 and CAM5.2 and α-SMA. In all cases of müllerian adenosarcomas, hypercellular areas consisting of CD10-positive neoplastic spindle cells with strong staining intensity were accentuated in a concentric fashion around the neoplastic glands or cystic spaces (Fig. 5). Of note, in two high-grade leiomyosarcomas, neoplastic cells with pleomorphic nuclei and abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm showed strong and extensive cytoplasmic staining for CD10 (Fig. 6). Normal endometrial stroma that was evaluated as an internal control was diffusely positive for CD10, whereas myometrium was negative for CD10.

DISCUSSION

Distinction between low-grade ESS and cellular leiomyoma or low-grade leiomyosarcoma can be a problem in the practice of surgical pathology. A constellation of features, that is, resemblance to proliferative-phase endometrial stroma, characterized by closely packed small to medium-sized uniform cells with spindle-shaped or plump ovoid nuclei and numerous small vessels mimicking the spiral arteries and by infiltrative growth in the myometrium, have been considered to be diagnostic. However, occasional smooth muscle differentiation in ESS as represented by expression of α-SMA and/or desmin (24, 25, 26) may lead to an erroneous interpretation of the results of immunohistochemistry. h-Caldesmon is considered to be a specific smooth muscle marker that is positive in well-differentiated smooth muscle cells and negative even in desmin- and/or α-SMA-positive ESS and thus is considered to be useful in distinguishing smooth muscle tumor from ESS (27, 28). Therefore, currently a panel employing a combination of CD10 and h-caldesmon seems contributory in making the distinction between ESS and smooth muscle tumor.

The current study disclosed that MMMTs and adenosarcomas showed distinct cytoplasmic staining for CD10. Recently, four studies have addressed the issue of the utility of CD10 for the diagnosis of ESS, but there has been insufficient information on CD10 expression in MMMTs and adenosarcomas (20, 21, 22, 23). Only one case of uterine MMMT in the series examined by McCluggage et al. had endometrial stromal components positive for CD10, showing focal and weak immunoreactivity (22). In 11 (92%) of 12 cases of MMMTs and all six (100%) cases of adenosarcoma in our series, sarcomatous components were positive for CD10 with moderate to strong staining intensity and intermediate to extensive distribution. These results are considered significant in contrast to a variety of mesenchymal tumors hitherto examined. Chu and Arber (8) demonstrated that rhabdomyosarcoma most frequently expressed CD10 with a positive rate of 60% (3/5), which was followed by liposarcoma (50%), schwannoma (45%), epithelioid sarcoma (28%), and leiomyosarcoma (6%). These observations indicate that CD10 expression in the sarcomatous component of MMMTs and adenosarcomas is more than coincidental.

From the view of tumorigenesis, it seems reasonable that the sarcomatous component in MMMTs and adenosarcoma, both of which are müllerian derived, show differentiation into the endometrial stroma as represented by CD10 expression. Interestingly, one high-grade endometrial sarcoma in our series, predominantly involving the endometrium and inner half of the myometrium, showed immunoreactivity for CD10, which suggests a possible endometrial stromal origin, although in the current view the use of the term high-grade endometrial stromal sarcoma is not preferred to designate such a tumor because of absence of distinct evidence of stromal differentiation in the literature (29, 30, 31).

In general, MMMT can be distinguished from low-grade ESS by high-grade morphology of the sarcomatous component, occasional heterologous components such as cartilage or striated muscle, and the coexistence of malignant epithelial components, which can be serous, endometrioid, mucinous, and/or squamous cell carcinoma, whereas adenosarcoma is distinguished by a mixture of benign-looking müllerian-type epithelium and sarcomatous components. In MMMTs and adenosarcoma, however, sarcomatous components can be prominent and may vary in degree of atypia, ranging from low-grade to high-grade, both of which can be CD10 positive. Therefore, in cases in which only limited sampling has been possible, the distinction between these tumors could be difficult, and in such situations immunohistochemistry for CD10 expression might be misleading.

Other notable findings are the existence of CD10-positive carcinomatous components and rhabdomyoblastic cells in MMMTs. Occasionally both CD10 and keratin-positive spindle cells in sarcomatous components and CD10-positive carcinomatous components link epithelial and nonepithelial components in the histogenesis of MMMT. The origin of MMMT has been a controversial issue, but some investigators favor an epithelial nature of the tumor based on the observation that its biologic behavior is closer to endometrial carcinoma rather than true sarcoma (32, 33) and that both tumors are related to the same etiologic factors (34). Therefore, it seems possible that the CD10-positive sarcomatous component is a derivative of CD10-positive epithelial components through the process of mesenchymal metaplasia. Another explanation is that epithelial and nonepithelial components originate from common stem cells independently. Nevertheless, the significance of CD10 expression in both epithelial and nonepithelial components remains to be defined.

Myoglobin- and/or desmin-positive rhabdomyoblastic cells with abundant eosinophilic and filamentous cytoplasm in MMMTs and adenosarcomas were consistently CD10 positive, as they were in the one primary uterine rhabdomyosarcoma. Chu and Arber (8) demonstrated that 3 (60%) of 5 extrauterine rhabdomyosarcomas were also positive for CD10, suggesting CD10 expression is not restricted to rhabdomyoblastic cells in uterine tumors. On the other hand, the intimate relationship between endometrial stroma and skeletal muscle differentiation is suggested by the rare examples of stromal nodule with skeletal muscle differentiation (35), ESS with rhabdoid differentiation (36), and adenomyofibroma with skeletal muscle differentiation (37). Therefore, CD10 expression might be a common phenotypic characteristic suggesting müllerian derivation of rhabdomyoblastic cells, although this subject requires further studies and assessment.

In our series, high-grade leiomyosarcomas showed distinct and extensive immunoreactivity for CD10 in areas. Recent studies have also shown that a small population of leiomyoma and leiomyosarcoma are focally positive for CD10 (20, 21, 22). Although CD10 expression in smooth muscle tumors seems an uncommon event, high-grade leiomyosarcomas still need to be examined because our data suggest that CD10 expression is not contributory in distinguishing between ESS and high-grade leiomyosarcoma. The significance of CD10 expression in smooth muscle tumors also remains unclear, but it is possible that CD10 expression represents true endometrial stromal differentiation.

In summary, the current study has disclosed that the sarcomatous components of MMMTs as well as adenosarcoma are almost always positive for CD10. In addition, high-grade endometrial sarcoma and leiomyosarcoma can also be positive. Therefore, distinction between these tumors should rely on a constellation of morphologic features combined with CD10 immunohistochemistry. CD10 expression might be a common immunophenotypic characteristic of neoplastic mesenchymal cells of müllerian origin, which is shared by ESS, MMMT, adenosarcoma, rhabdomyosarcoma, and leiomyosarcoma. The significance of CD10 expression still needs to be pursued by further studies.

References

Greaves MF, Hariri G, Newman RA, Sutherland DR, Ritter MA, Ritz J . Selective expression of the common acute lymphoblastic leukemia (gp 100) antigen on immature lymphoid cells and their malignant counterparts. Blood 1983; 61: 628–639.

Weiss LM, Bindl JM, Picozzi VJ, Link MP, Warnke RA . Lymphoblastic lymphoma: an immunophenotype study of 26 cases with comparison to T cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Blood 1986; 67: 474–478.

Gregory CD, Tursz T, Edwards CF, Tetaud C, Talbot M, Caillou B, et al. Identification of a subset of normal B cells with a Burkitt's lymphoma (BL)-like phenotype. J Immunol 1987; 139: 313–318.

Stein H, Lennert K, Feller AC, Mason DY . Immunohistological analysis of human lymphoma: correlation of histological and immunological categories. Adv Cancer Res 1984; 42: 67–147.

Holm-Nielsen P, Pallesen G . Expression of segment-specific antigens in the human nephron and in renal epithelial tumors. APMIS Suppl 1988; 4: 48–55.

Droz D, Zachar D, Charbit L, Gogusev J, Chretein Y, Iris L . Expression of the human nephron differentiation molecules in renal cell carcinomas. Am J Pathol 1990; 137: 895–905.

Avery AK, Beckstead J, Renshaw AA, Corless CL . Use of antibodies to RCC and CD10 in the differential diagnosis of renal neoplasms. Am J Surg Pathol 2000; 24: 203–210.

Chu P, Arber DA . Paraffin-section detection of CD10 in 505 nonhematopoietic neoplasms. Frequent expression in renal cell carcinoma and endometrial stromal sarcoma. Am J Clin Pathol 2000; 113: 374–382.

Dragovic T, Sekosan M, Becker RP, Erdos EG . Detection of neutral endopeptidase 24.11 (neprilysin) in human hepatocellular carcinomas by immunocytochemistry. Anticancer Res 1997; 17: 3233–3238.

Xiao SY, Wang HL, Hart J, Fleming D, Beard MR . cDNA arrays and immunohistochemistry identification of CD10/CALLA expression in hepatocellular carcinoma. Am J Pathol 2001; 159(4): 1415–1421.

Sato Y, Itoh F, Hinoda Y, Ohe Y, Nakagawa N, Ueda R, et al. Expression of CD10/neutral endopeptidase in normal and malignant tissues of the human stomach and colon. J Gastroenterol 1996; 31: 12–17.

Notohara K, Hamazaki S, Tsukayama C, Nakamoto S, Kawabata K, Mizobuchi K, et al. Solid-pseudopapillary tumor of the pancreas: immunohistochemical localization of neuroendocrine markers and CD10. Am J Surg Pathol 2000; 24: 1361–1371.

Satoh F, Tsutsumi Y, Yokoyama S, Osamura RY . Comparative immunohistochemical analysis of developing kidneys, nephroblastomas and related tumors: considerations on their histogenesis. Pathol Int 2000; 50: 458–471.

Carrel S, de Tribolet N, Gross N . Expression of HLA-DR and common acute lymphoblastic leukemia antigens on glioma cells. Eur J Immunol 1982; 12: 354–357.

Monod L, Hamou MF, Ronco P, Verroust P, de Tribolet N . Expression of cALLa/NEP on gliomas: a possible marker of malignancy. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 1992; 114: 3–7.

Brox AG, Lavallee MC, Arseneau J, Langleben A, Major PP . Expression of common acute lymphoblastic leukemia-associated antigen on germ cell tumor. Am J Med 1986; 80: 1249–1252.

Kanitakis J, Bourchany D, Claudy A . Expression of the CD10 antigen (neutral endopeptidase) by mesenchymal tumors of the skin. Anticancer Res 2000; 20: 3539–3544.

Imai K, Kanzaki H, Fujiwara H, Kariya M, Okamoto N, Takakura K, et al. Expression of aminopeptidase N and neutral endopeptidase on the endometrial stromal cells in endometriosis and adenomyosis. Hum Reprod 1992; 7: 1326–1328.

Imai K, Maeda M, Fujiwara H, Okamoto N, Kariya M, Emi N, et al. Human endometrial stromal cells and decidual cells express cluster of differentiation (CD) 13 antigen/aminopeptidase N and CD10 antigen/neutral endopeptidase. Biol Reprod 1992; 46: 328–334.

Chu PG, Arber DA, Weiss LM, Chang KL . Utility of CD10 in distinguishing between endometrial stromal sarcoma and uterine smooth muscle tumors: an immunohistochemical comparison of 34 cases. Mod Pathol 2001; 14: 465–471.

Agoff SN, Grieco VS, Garcia R, Gown AM . Immunohistochemical distinction of endometrial stromal sarcoma and cellular leiomyoma. Appl Immunohistochem Mol Morphol 2001; 9: 164–169.

McCluggage WG, Sumathi VP, Maxwell P . CD10 is a sensitive and diagnostically useful immunohistochemical marker of normal endometrial stroma and of endometrial stromal neoplasms. Histopathology 2001; 39: 273–278.

Toki T, Shimizu M, Takagi Y, Ashida T, Konishi I . CD10 is a marker for normal and neoplastic endometrial stromal cells. Int J Gynecol Pathol 2002; 21: 41–47.

Franquemont DW, Frierson HF Jr, Mills SE . An immunohistochemical study of normal endometrial stroma and endometrial stromal neoplasms. Evidence for smooth muscle differentiation. Am J Surg Pathol 1991; 15: 861–870.

Lillemoe TJ, Perrone T, Norris HJ, Dehner LP . Myogenous phenotype of epithelial-like areas in endometrial stromal sarcomas. Arch Pathol Lab Med 1991; 115: 215–219.

Farhood AI, Abrams J . Immunohistochemistry of endometrial stromal sarcoma. Hum Pathol 1991; 22: 224–230.

Nucci MR, O'Connell JT, Huettner PC, Cviko A, Sun D, Quade BJ . h-Caldesmon expression effectively distinguishes endometrial stromal tumors from uterine smooth muscle tumors. Am J Surg Pathol 2001; 25: 455–463.

Rush DS, Tan J, Baergen RN, Soslow RA . h-Caldesmon, a novel smooth muscle-specific antibody, distinguishes between cellular leiomyoma and endometrial stromal sarcoma. Am J Surg Pathol 2001; 25: 253–258.

Evans HL . Endometrial stromal sarcoma and poorly differentiated endometrial sarcoma. Cancer 1982; 50: 2170–2182.

Chang KL, Crabtree GS, Lim-Tan SK, Kempson RL, Hendrickson MR . Primary uterine endometrial stromal neoplasms. A clinicopathologic study of 117 cases. Am J Surg Pathol 1990; 14: 415–438.

Kempson RL, Hendrickson MR . Smooth muscle, endometrial stromal, and mixed Mullerian tumors of the uterus. Mod Pathol 2000; 13: 328–342.

Silverberg SG, Major FJ, Blessing JA, Fetter B, Askin FB, Liao SY, et al. Carcinosarcoma (malignant mixed mesodermal tumor) of the uterus. A Gynecologic Oncology Group pathologic study of 203 cases. Int J Gynecol Pathol 1990; 9: 1–19.

Bitterman P, Chun B, Kurman RJ . The significance of epithelial differentiation in mixed mesodermal tumors of the uterus. A clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical study. Am J Surg Pathol 1990; 14: 317–328.

Zelmanowicz A, Hildesheim A, Sherman ME, Sturgeon SR, Kurman RJ, Barrett RJ, et al. Evidence for a common etiology for endometrial carcinomas and malignant mixed mullerian tumors. Gynecol Oncol 1998; 69: 253–257.

Lloreta J, Prat J . Endometrial stromal nodule with smooth and skeletal muscle components simulating stromal sarcoma. Int J Gynecol Pathol 1992; 11: 293–298.

Kim YH, Cho H, Kyeom-Kim H, Kim I . Uterine endometrial stromal sarcoma with rhabdoid and smooth muscle differentiation. J Korean Med Sci 1996; 11: 88–93.

Sinkre P, Miller DS, Milchgrub S, Hameed A . Adenomyofibroma of the endometrium with skeletal muscle differentiation. Int J Gynecol Pathol 2000; 19: 280–283.

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr. Yasuo Nakata at Hyogo Medical School Hospital, Dr. Yasumasa Monobe at Kawasaki Hospital, Okayama, and the Laboratory of Pathology, Tokyo Health Service Association, Tokyo, Japan for contributing a portion of the materials for the current study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Mikami, Y., Hata, S., Kiyokawa, T. et al. Expression of CD10 in Malignant Müllerian Mixed Tumors and Adenosarcomas: An Immunohistochemical Study. Mod Pathol 15, 923–930 (2002). https://doi.org/10.1097/01.MP.0000026058.33869.DB

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1097/01.MP.0000026058.33869.DB

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Pleomorphic Rhabdomyosarcoma of Uterus in an Adult Female: A Rare Entity

Indian Journal of Gynecologic Oncology (2023)

-

The values of Transgelin, Stathmin, BCOR and Cyclin-D1 expression in differentiation between Uterine Leiomyosarcoma (ULMS) and Endometrial Stromal Sarcoma (ESS); diagnostic and prognostic implications

Surgical and Experimental Pathology (2020)

-

IFITM1 is a Novel, Highly Sensitive Marker for Endometriotic Stromal Cells in Ovarian and Extragenital Endometriosis

Reproductive Sciences (2020)

-

Uterine Adenosarcoma: a Review

Current Oncology Reports (2016)

-

Small cell carcinoma in endometrium on the base of extensive adenomyosis: differential diagnosis with immunochemistry

International Cancer Conference Journal (2012)