Abstract

The cell of origin and direction of differentiation of the clear cell tumor of the lung (the so-called sugar tumor) remains enigmatic. Recognition of HMB-45 immunoreactivity and identification of melanosomes have suggested a relationship to angiomyolipoma of kidney or liver and lymphangiomyoma. This has given rise to the concept that clear cell tumors are neoplasms of so-called perivascular epithelioid cells—PEComas. Herein we report the existence of four similar tumors occurring in extrapulmonary sites, one of which had malignant features. The three benign tumors occurred in females ages 9, 20, and 40 years; two were located in the rectum and one in the vulva. The malignant tumor occurred in the inter-atrial cardiac septum of a 29-year-old man. Common histologic features were a richly vascular organoid architecture, tumor cells with clear to pale eosinophilic cytoplasm, abundant glycogen, and immunoreactivity for HMB 45, but not S100, multiple keratin, neuroendocrine, or muscle markers. Benign tumors demonstrated low mitotic activity, no necrosis, and good circumscription; the malignant tumor showed considerable mitotic activity, necrosis, and an infiltrative growth pattern. Ultrastructurally, glycogen was present, mitochondria were abundant, and membrane-bound lamellated bodies consistent with premelanosomes were present in two cases, and equivocal in one.

Because these tumors have light microscopic, immunohistochemical, and electron microscopic features similar to pulmonary sugar tumors, we propose the name primary extrapulmonary sugar tumor (PEST) for them. Although most PEST’s are probably benign, malignant forms appear to exist. These cases further support the concept of a family of systemic HMB-45 positive tumors that include sugar tumors, angiomyolipoma of kidney or liver, lymphangiomyomas, and clear-cell myomelanocytic tumors of the falciform ligament/ligamentum teres.

Similar content being viewed by others

INTRODUCTION

The benign clear cell tumor of the lung, also known as “sugar” tumor of the lung, is a very rare and somewhat controversial entity. The tumor was initially described by Liebow and Castleman in 1963 (1) as “benign ‘clear cell tumor’” of the lung. Subsequently, the same authors reported 12 examples of this tumor, using the modified term “benign clear cell (‘sugar’) tumor” of the lung (2). In a 1985 review, Andrion et al. (3)had only identified an additional 10 tumors in the world literature.

The origin of “sugar” tumors of the lung has been debated. Although early studies suggested origin from smooth muscle or pericytes (4), neuroendocrine (Kulchitsky) cells (5, 6), and epithelial nonciliated bronchiolar (Clara) or serous cells (3), more recent studies have noted reactivity for HMB-45 (7, 8, 9) and have shown ultrastructural evidence of melanocytic differentiation (9). Expanding on the latter concepts, Bonetti et al. proposed that clear cell tumors of the lung arise from the “perivascular epithelioid cell” or “PEC” and noted that similar cells have been identified in angiomyolipomas and lymphangiomyomas (7). In reporting a pancreatic sugar tumor, the same authors propose the term “PEComa” to describe these lesions (10).

Herein we report four additional extrapulmonary clear cell tumors, one apparently malignant, having light microscopic, immunohistochemical, and ultrastructural features similar to “sugar” tumors of the lung.

METHODS AND MATERIALS

Putative cases of extrapulmonary sugar tumors were identified from the consultation files of the authors based on the histologic, immunohistochemical, and ultrastructural findings described below. One case has been previously reported (11). All tumors had been formalin-fixed, processed routinely, and stained with hematoxylin and eosin, and Periodic Acid Schiff (PAS) with and without diastase predigestion. Immunoperoxidase stains were performed on paraffin-embedded tissue using the antibodies and dilutions shown in Table 1. Transmission electron microscopy was performed in a routine fashion by retrieval of tissue from the paraffin block or from glutaraldehyde-fixed tissue as available. Pertinent clinical history and follow-up were obtained from referring physicians.

Case Histories

A summary of the pertinent clinical findings is presented in Table 2. The case histories follow.

Case 1: An otherwise healthy 9-year-old girl presented with a prolapsing rectal tumor, which was excised transanally. The tumor measured 3.0 cm in greatest dimension and showed a glistening pale tan appearance. Without additional therapy, the patient is alive and well 14 months postoperatively.

Case 2: A 20-year-old otherwise healthy woman was noted to have a 2 cm in diameter partially cystic perineal perineum tumor, which was excised in three fragments. She has received no further therapy and is well four years later with no evidence of recurrence or metastasis.

Case 3: A 29-year-old man with a seven-year history of atrial fibrillation presented with symptoms of mitral stenosis. After work-up, he underwent a thoracotomy that revealed a left atrial tumor growing through the interatrial septum to involve right atrium and extending throughout the left lateral wall into the pericardial sac. Grossly, the tumor appeared to extend very near the pulmonary veins. Because of its infiltrative nature, only incisional biopsies were taken at initial operation. Grossly, the tumor appeared pale yellow. Subsequently, the tumor was resected and left atrial reconstruction performed with a bovine graft and reimplantation of pulmonary veins. The patient died shortly thereafter of cardiac failure thought to be due to nontumorous coronary artery thromboemboli. At postmortem examination, no residual primary or metastatic tumor was found.

Case 4: A 40-year-old woman, who was otherwise healthy, presented with a recent history of profuse rectal bleeding. At colonoscopy, a lesion was noted on the anterior wall of the rectum at 8–10 cm, which was snared and brought down to near the anal opening. Upon mucosal incision, the lesion “popped out.” Grossly, the tumor was centrally cystic and had a friable, red to yellow appearance. Computed tomography of the pelvis, abdomen, and retroperitoneum were negative. Vaginal exam showed no apparent connection to the rectal lesion. The patient is alive and well at 6 months without further treatment.

Pathologic Findings

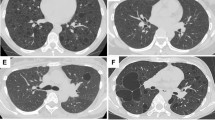

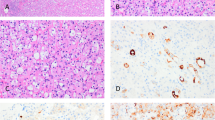

The tumors were comprised of the following: 1) plump, epithelioid cells with abundant clear to lightly eosinophilic cytoplasm with 2) round, medium-sized nuclei with occasional moderately sized nucleoli, and 3) a zellballen type architecture with small tumor nests separated by thin fibrous septa containing capillaries (Fig. 1). In the benign cases (Cases 1, 2, and 4), the tumor borders were fairly well circumscribed but nonencapsulated. Mitotic figures were rare, and there was no necrosis, frank anaplasia, or vascular invasion. In contrast, the presumed malignant tumor from Case 3 demonstrated extensive necrosis, locally infiltrative growth, and probable vascular invasion (Fig. 2), had scattered pleomorphic nuclei, moderately sized nucleoli, a high mitotic rate, (45/10 high powered fields), and scattered atypical mitotic figures.

Cardiac PEST, likely malignant (Case 3). Epithelioid cells with clear cytoplasm and an organoid growth pattern. Numerous mitotic figures are present, some of which are atypical (A). Features further suggesting malignancy are tumor necrosis (B), locally infiltrative growth (C), and probable vascular invasion (D; all hematoxylin-eosin).

In Case 1, the tumor was predominantly submucosal, although the mucosa was involved focally. The neoplasm was adjacent to a prominent mucosal vessel, possibly lymphatic (Fig. 3). In Case 4, moderate amounts of hemosiderin and lesser amounts of hematoidin pigment were present but melanin was not identified. Focally, dilated racemose spaces suggestive of lymphatic structures were evident (Fig. 4).

All tumors demonstrated PAS-positive granules which were abolished with diastase digestion, consistent with significant cytoplasmic glycogen (Table 3). Immunohistochemical analysis revealed positive staining with antibody against HMB-45 in all cases (Fig. 5), weak vimentin reactivity in Case 1, and a lack of reactivity with S-100 protein and the remainder of the antibodies shown in Table 1.

Ultrastructural features are summarized in Table 3. In case 1, there were scattered premelanosomes (Fig. 6) and prominent cytoplasmic glycogen but no neurosecretory granules, junctions or desmosomes. Case 4 contained clustered cytoplasmic structures highly suspicious for premelanosomes, however sufficient internal structures was not present for a definitive determination. In Case 3, rare structures equivocal for premelanosomes were noted, however, cytoplasmic microtubular aggregates were present. Case 2 was similar to the others, but premelanosomes were not demonstrated.

DISCUSSION

The common features of the tumors described herein are an organoid, paraganglioma-like architecture, clear glycogen-rich cytoplasm, lack of immunohistochemical or ultrastructural evidence of epithelial origin, and immunoreactivity for HMB-45. In addition, premelanosomes or premelanosome-like structures were identified in three of four cases. Because these features have all been described in so-called clear cell (“sugar”) tumors of the lung, we have proposed the name primary extrapulmonary sugar tumors, or “PEST’s,” to describe this entity. The acronym is apropos, since the tumors reported herein have been difficult to diagnose and classify, and it retains the historical connection to clear cell ‘sugar’ tumors.

Although similar lesions may have been reported under other names, to our knowledge, only four previous reports of primary, extrapulmonary sugar tumors exist - a benign tracheal lesion (12), a presumed benign pancreas tumor (10), a rectal lesion (reported previously in Ref. 11, but presented in more detail here), and a uterine lesion (14). Similar tumors which have evidence of smooth muscle differentiation as well as melanocytic differentiation and which have a particular predilection for the ligamentum teres and falciform ligament in children have also been report (15, 16).

The majority of pulmonary sugar tumors have been benign, hence the oft-used synonym “benign clear cell tumors.” However, Sale et al. have reported one that metastasized to the liver ten years after resection of the primary lesion (17). A case recently reported by Ribalta et al. (18) may also represent another malignant example as is the case mentioned by Bonetti et al. in a review (13). The presence of columnar cells in some cases and necrosis in others has led Dail to caution that generalizations about the behavior of these tumors might not be wise (19). Three of our cases have shown no clinical or histologic evidence of malignancy and the patients remain healthy 8, 14, and 48 months postoperatively. We regard our Case 3, however, as malignant by virtue of the locally infiltrative growth pattern, probable vascular invasion, high mitotic rate, and necrosis. Of note, the putative malignant pulmonary sugar tumor reported by Sale et al. also showed necrosis, similar to our case.

HMB-45 is a monoclonal antibody developed by Gown et al. in 1985 from an extract of metastatic melanoma which showed absolute specificity for melanocytic tumors in their hands (20) and is now known to react with gp100 (21). Despite some problems with contamination in a commercially available source (22, 23, 24, 25, 26) recent experience suggests that HMB-45 very rarely stains non-melanocytic tumors.

Reproducible HMB-45 staining has been identified in tuberous-sclerosis associated hamartomatous lesions not traditionally thought to be melanocytic in origin. Nearly all renal and hepatic angiomyolipomas (27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33) and cases of lymphangioleiomyomatosis (27, 29, 34) have shown HMB-45 reactivity. The occasional ultrastructural identification of melanosomes or premelanosomes (29, 31) suggests the reactivity is not spurious.

A putative association between angiomyolipomas and sugar tumors of the lung was initially proposed by Bonetti et al. (7). They noted HMB-45 reactivity in 3 of 3 sugar tumors of the lung, as had been noted by others previously (8), and suggested that this immunoreactivity, coupled with the resemblance of the glycogen-rich cells of the sugar tumor to the perivascular epithelioid component of angiomyolipoma and lymphangioleiomyomatosis (30, 35), and the finding of intratumoral mature adipose tissue in one pulmonary sugar tumor, suggests that these tumors are members of the same family. Unlike our cases, angiomyolipoma and lymphangioleiomyomatosis also typically show light microscopic, immunohistochemical, and ultrastructural evidence of smooth muscle differentiation. Interestingly, two of our cases (1 and 4) had some aberrant, dilated vascular channels which may represent abnormal lymphatic spaces, further supporting a connection between PEST lesions and lymphangioleiomyomatosis. Our patients did not have known stigmata of tuberous sclerosis.

For the sugar tumor/angiomyolipoma/lymphangiomyoma family of tumors, Zamboni and colleagues (10) propose the term PEComa, meant to describe a tumor composed purely of the perivascular epithelioid cell component of this family of tumors. We agree with their concept, although the term “PEComa” may inappropriately imply that all tumors are benign. Hence, we suggest the term PEST as described above.

The major differential diagnosis for PEST’s includes paraganglioma, malignant melanoma, and clear cell sarcoma. Although the “zellballen” architecture closely resembles that seen in paraganglioma, the lack of neuron specific enolase, chromogranin, and synaptophysin reactivity, or S-100 positive sustentacular cells, but reactivity for HMB-45 and the presence of premelanosomes ultrastructurally in the absence of neurosecretory granules, should allow distinction from paraganglioma. Using an Enzo HMB-45 antibody, focal (<5% of cells) HMB-45 reactivity has been noted in a minority of pheochromocytomas (36), although others, also using an Enzo product, have failed to detect HMB-45 in any of 19 pheochromocytomas and paragangliomas (37). A single pigmented pulmonary carcinoid tumor has also been reported to show rare melanosomes in heavily pigmented S-100 protein and HMB-45 positive sustentacular cells (38).

The distinction between PEST, and malignant melanoma and clear cell sarcoma may be a bit more difficult, particularly when significant mitotic activity and necrosis are seen, as in our Case 3. The majority of malignant melanomas will show both S-100 protein and vimentin reactivity (39) whereas PEST’s appear to be uniformly S-100 protein negative and are generally vimentin negative. In histologically benign PEST’s, the low mitotic activity and lack of necrosis are helpful. The presence of a neoplasm in a primary site unusual for malignant melanoma, particularly when no other lesions are found, is also helpful supportive clinical evidence for a PEST. This diagnostic dilemma may occasionally be insoluble as highlighted by the recently reported case of Ribalta et al. (18). Clear cell sarcoma is a reasonable diagnostic consideration in our Case 3. We feel this likely represents a malignant form of PEST, however, since the heart would be an unusual site for primary clear cell sarcoma, no other putative primary sites or synchronous lesions were noted at autopsy, and the majority of clear cell sarcomas are vimentin positive and S-100 protein positive (40).

One final neoplasm which could be confused with PEST’s is the recently described melanocytic clear cell neoplasm of the kidney (41). These tumors also have a richly vascular alveolar growth pattern and are composed of cells with abundant clear cytoplasm. But, in addition to showing reactivity for HMB-45, tyrosinase and melan A, they show focal reactivity with antibodies to keratin and EMA, unlike PEST’s

A reasonable approach for PEST’s without significant mitotic activity, necrosis, local or angiolymphatic invasion is conservative local excision and periodic follow-up. Case 3 represents a presumably malignant form of PEST which may be analogous to the malignant form of clear cell tumor of the lung reported by Sale et al. (17) and Bonetti et al. (13). Additional cases of putative aggressive forms of PEST will need to be studied in order to gain more insight into their behavior.

References

Liebow AA, Castleman B . Benign “clear cell tumors” of the lung [abstract]. Am J Pathol 1963; 43: 13a–14a.

Liebow AA, Castleman B . Benign clear cell (“sugar”) tumors of the lung. Yale J Biol Med 1971; 43: 213–222.

Andrion A, Mazzucco G, Gugliotta P, Monga G . Benign clear cell (sugar) tumor of the lung. A light microscopic, histochemical, and ultrastructural study with a review of the literature. Cancer 1985; 56: 2657–2663.

Hoch WS, Patchefsky AS, Takeda M, Gordon G . Benign clear cell tumor of the lung. An ultrastructural study. Cancer 1974; 33: 1328–1336.

Becker NH, Soifer I . Benign clear cell tumor (“sugar tumor”) of the lung. Cancer 1971; 27: 712–719.

Harbin WP, Mark GJ, Greene RE . Benign clear-cell tumor (“sugar” tumor) of the lung: a case report and review of the literature. Radiology 1978; 129: 595–596.

Bonetti F, Pea M, Martignoni G, Doglioni C, Zamboni G, Capelli P, et al. Clear cell (“sugar”) tumor of the lung is a lesion strictly related to angiomyolipoma–the concept of a family of lesions characterized by the presence of the perivascular epithelioid cells (PEC). Pathology 1994; 26 (3): 230–236.

Gal AA, Koss MN, Hochholzer L, Chejfec G . An immunohistochemical study of benign clear cell (“sugar”) tumor of the lung. Arch Pathol Lab Med 1991; 115: 1034–1038.

Gaffey MJ, Mills SE, Zarbo RJ, Weiss LM, Gown AM . Clear cell tumor of the lung. Immunohistochemical and ultrastructural evidence of melanogenesis. Am J Surg Pathol 1991; 15: 644–653.

Zamboni G, Pea M, Martignoni G, Zancanaro C, Faccioli G, et al. Clear cell “sugar” tumor of the pancreas. A novel member of the family of lesions characterized by the presence of perivascular epithelioid cells. Am J Surg Pathol 1996; 20: 722–730.

Fetsch PA, Fetsch JF, Marincola FM, Travis W, Batts KP, Abati A . Comparison of melanoma antigen recognized by T cells (MART-1) to HMB-45: additional evidence to support a common lineage for angiomyolipoma, lymphangiomyomatosis, and clear cell sugar tumor. Mod Pathol 1998; 11: 699–703.

Kung M, Landa JF, Lubin J . Benign clear cell tumor (“sugar tumor”) of the trachea. Cancer 1984; 54: 517–519.

Bonetti F, Pea M, Martignoni G, Zamboni G, Manfrin E, Colombari R, et al. The perivascular epithelioid cell and related lesions. Adv Anat Pathol 1997; 4: 343–358.

Pea M, Martignoni G, Zamboni G, Bonetti F . Perivascular epithelioid cell [letter]. Am J Surg Pathol 1996; 20: 1149–1153.

Tanaka Y, Ijiri R, Kato K, Kato Y, Misugi K, Nakatani Y, et al. HBM-45/Melan-A and smooth muscle actin-positive clear-cell epithelioid tumor arising in the ligamentum teres hepatis. Am J Surg Pathol 2000; 24: 1295–2000.

Folpe AL, Goodman ZD, Ishak KG, Paulino AFG, Taboada EM, Meehan SA, et al. Clear cell myomelanocytic tumor of the falciform ligament/ligamentum teres. Am J Surg Pathol 2000; 24: 1239–1246.

Sale GE, Kulander BG . ’Benign’ clear-cell tumor (sugar tumor) of the lung with hepatic metastases ten years after resection of pulmonary primary tumor [letter]. Arch Pathol Lab Med 1988; 112: 1177–1178.

Ribalta T, Lloreta J, Munne A, Serrano S, Cardesa A . Malignant pigmented clear cell epithelioid tumor of the kidney: Clear cell (“sugar”) tumor versus malignant melanoma. Hum Pathol 2000; 31: 516–519.

Dail DH . Benign clear cell (“sugar”) tumor of lung [letter]. Arch Pathol Lab Med 1989; 113: 573–574.

Gown AM, Vogel AM, Hoak D, Gough F, McNutt MA . Monoclonal antibodies specific for melanocytic tumors distinguish subpopulations of melanocytes. Am J Pathol 1986; 123: 195–203.

Adema GJ, Bakker AB, de Boer AJ, Hohenstein P, Figdor CG . pMel17 is recognized by monoclonal antibodies NKI-beteb, HMB-45 and HMB-50 and by anti-melanoma CTL. Br J Cancer 1996; 73: 1044–1048.

Kornstein MJ, Franco AP . Specificity of HMB-45 [letter]. Arch Pathol Lab Med 1990; 114: 450.

Bacchi CE, Gown AM . Letter to the editor. Arch Pathol Lab Med 1992; 116: 899–900.

Bonetti F, Pea M, Martignoni G, Mombello A, Colombari R, Zamboni G, et al. False-positive immunostaining of normal epithelia and carcinomas with ascites fluid preparations of antimelanoma monoclonal antibody HMB-45. Am J Clin Pathol 1991; 95: 454–459.

Tatum AH, Friedman HD . Letter to the editor. Arch Pathol Lab Med 1992; 116: 900.

Litman DA, Cochran AJ, Hirshowitz SL . False positive HMB-45 staining of axillary apocrine cells [letter]. Acta Cytol 1994; 38: 489–490.

Ashfaq R, Weinberg AG, Albores-Saavedra J . Renal angiomyolipomas and HMB-45 reactivity. Cancer 1993; 71: 3091–3097.

Hoon V, Thung SN, Kaneko M, Unger PD . HMB-45 reactivity in renal angiomyolipoma and lymphangioleiomyomatosis. Arch Pathol Lab Med 1994; 118: 732–734.

Liwnicz BH, Weeks DA, Zuppan CW . Extrarenal angiomyolipoma with melanocytic and hibernoma-like features. Ultrastruct Pathol 1994; 18: 443–448.

Bonzanini M, Pea M, Martignoni G, Zamboni G, Capelli P, Bernardello F, et al. Preoperative diagnosis of renal angiomyolipoma: fine needle aspiration cytology and immunocytochemical characterization. Pathology 1994; 26: 170–175.

Kaiserling E, Krober S, Xiao JC, Schaumberg-Lever G . Angiomyolipoma of the kidney. Immunoreactivity with HMB-45. Light- and electron-microscopic findings. Histopathology 1994; 25: 41–48.

Kimura N, Kubota M, Nagura H . A hepatic tumor associated with bilateral renal angiomyolipomas: a variant of angiomyolipoma? Pathol Int 1994; 44: 540–547.

Tsui WM, Yuen AKT, Ma KF, Tse CCH . Hepatic angiomyolipomas with a deceptive trabecular pattern and HMB-45 reactivity. Histopathology 1992; 21: 569–573.

Guinee DG, Feuerstein I, Koss MN, Travis WD . Pulmonary lymphangioleiomyomatosis. Diagnosis based on results of transbronchial biopsy and immunohistochemical studies and correlation with high-resolution computed tomography findings. Arch Pathol Lab Med 1994; 118: 846–849.

Bonetti F, Pea M, Martignoni G, Zamboni G . PEC and sugar [letter]. Am J Surg Pathol 1992; 16: 307–308.

Unger PD, Hoffman K, Thung SN, Pertsimlides D, Wolfe D, Kaneko M . HMB-45 reactivity in adrenal pheochromocytomas. Arch Pathol Lab Med 1992; 116: 151–153.

Fraga M, Garcia-Caballero T, Antunez J, Couce M, Beiras A, Forteza J . A comparative immunohistochemical study of pheochromocytomas and paragangliomas. Histol Histopathol 1993; 8: 429–436.

Gal AA, Koss MN, Hochholzer L, DeRose PB, Cohen C . Pigmented pulmonary carcinoid tumor. An immunohistochemical and ultrastructural study. Arch Pathol Lab Med 1993; 117: 832–836.

King R, Busam K, Rosai J . Metastatic malignant melanoma resembling malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor. Am J Surg Pathol 1999; 23: 1499–1505.

Swanson PE, Wick MR . Clear cell sarcoma. An immunohistochemical analysis of six cases and comparison with other epithelioid neoplasms of soft tissue. Arch Pathol Lab Med 1989; 113: 55–60.

Davis CJ, Sesterhenn IA, Brinska R, Mastofi K . Melanocytic clear cell neoplasms of the kidney [abstract]. Mod Pathol 1999; 12: 93A.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Drs. John Casey, R. Bruce Wellman, Ronald Schuen, and Jarmila Fiser for contributing the cases for this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Tazelaar, H., Batts, K. & Srigley, J. Primary Extrapulmonary Sugar Tumor (PEST): A Report of Four Cases. Mod Pathol 14, 615–622 (2001). https://doi.org/10.1038/modpathol.3880360

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/modpathol.3880360

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Perivascular epithelioid cell tumor of the rectum: report of a case and review of the literature

World Journal of Surgical Oncology (2014)

-

Perivascular Epithelioid Cell Tumors (PEComas) of the Head and Neck: Report of Three Cases and Review of the Literature

Head and Neck Pathology (2011)

-

PEComas: the past, the present and the future

Virchows Archiv (2008)

-

Perivascular epithelioid cell tumor of the rib

Virchows Archiv (2008)