Abstract

Study design:

Case report.

Objective:

To present a patient with spinal brucellosis, which was initially presented with sciatica and misdiagnosed as a lumbar disc herniation owing to nonspecific neurological and radiological findings. The delay in diagnosis led to rapid progression of the disease and complications.

Setting:

Department of Neurosurgery at a tertiary university teaching hospital (Sutcu Imam University Medical Center in Turkey).

Case report:

A 57-year-old woman with a history of low-back pain for 6 months, fatigue, and severe left-sided sciatica for the last 3 months presented to our hospital. Three months earlier, at another hospital, she had had a negative Rose-Bengal test for brucellosis and a lumbar computed tomography performed at that time showed only minimal L4–5 annular bulging. For 2 months, she was treated with analgesics for ‘lumbar disc herniation’ without relief of pain. On presentation to our department, her magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) examination showed edema and minimal annular bulging at L3–4 and L4–5. When her Rose-Bengal test returned positive, she was started on triple antibiotics for presumed Brucella infection. When symptoms and neurologic signs worsened while taking antibiotics, repeat MRI scan showed a spinal epidural abscess at the L4–5 level. Emergent surgery and 8 weeks of antibiotics resulted in cure.

Conclusion:

In areas endemic for brucellosis, subtle historical and exam features should be sought to exclude an infection such as brucellar sponylo-discitis. Appropriate serological tests should be readily available to confirm or exclude this diagnosis in selected patients, to avoid delays in antibiotic treatment.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Brucellosis is caused by Gram-negative intracellular bacteria of the genus Brucella. Brucellosis is endemic in the Mediterranean basin1, 2, 3 and occurs in 0.59 per 100 000 per annum in Turkey.4 Infection from Brucella species can affect multiple systems, musculoskeletal system being the most common, and thus health-care providers from a variety of medical specialities may be involved in the care of these patients.5, 6 Spondylitis secondary to brucellosis was first described by Kulowski and Vinke in 19327 and is present in 9–12% of brucellosis patients.8, 9 Spinal brucellosis mainly affects the end plates of lumbar vertebrae, and can cause formation of granulation tissue with resulting sciatica. The patient presentation may mimic that of lumbar disc herniation.4 The purpose of this case report is to highlight the need to consider this diagnosis in endemic areas in patients who present with low-back pain and/or sciatica, in order to minimize diagnostic delays and treatment errors.

Case report

A 57-year-old housewife was referred to our tertiary care university hospital (serving a surrounding population of approximately two million) with a history of low-back pain for 6 months and severe left-sided sciatica for the past 3 months. By history, her laboratory studies were normal and Rose-Bengal test for brucellosis was negative 3 months earlier. A lumbar computed tomography (CT), which was obtained in the previous hospital, showed minimal L4–5 annular bulging (no surgical indication was present). She was treated for ‘lumbar disc herniation’ with analgesics for 2 months without any relief in her pain.

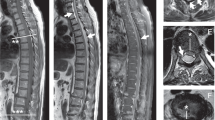

When the patient presented to our clinic, constant and severe midline low-back pain radiating to the left leg and fatigue were the main symptoms. Vital signs were as follows: temperature 37.8°C, pulse 86/min, BP 140/90 mm Hg, and respiration rate. 32/min. She had noticeable paravertebral muscle spasm and moderate tenderness to palpation in the L4–5 area. Neurological examination revealed hypoesthesia in the left L5 and S1 dermatomes and 4/5 muscle strength in the left extensor hallucis longus muscle. The erythrocyte sedimentation rate was 56 mm and C-reactive protein 72 mg/l. Plain films of the lumbar area revealed only L4–5 disc space narrowing. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the low-back area showed acute edema of the body of L5 and minimal annular bulging at L3–4 and L4–5 (Figure 1). Because her excruciating pain and neurological deficits were inconsistent with the imaging results and diagnosis of ‘lumbar disc herniation’, a technetium bone scintigraphy was performed. This showed increased uptake at the affected L4 and L5 lumbar spinal segments, consistent with infection (Figure 2). Serological studies were carried out in order to ascertain the causative organism and this time the Rose-Bengal test was positive. The Wright sero-agglutination titer was over 1/160 (Brucella abortus M101, Cromatest®, Linear Chemicals, Spain) and the Brucella anti-human globulin titer was 1/640. Blood cultures were negative for Brucella species.

The patient was diagnosed with spondylo-discitis due to Brucella and was treated with oral doxycycline 100 mg b.i.d., rifampicin 600 mg/day, and ciprofloxacin 500 mg b.i.d. In spite of triple antibiotic therapy, her pain worsened, which led us to obtain a multislice CT in order to evaluate the bone lesions in a more detailed manner. Irregular bone defects were observed on end plates bordering the L4–5 intervertebral disc space (Figure 3). On the 15th day of the medical antibiotic therapy in the hospital, the patient exhibited sudden progression of her neurological deficits (now 1/5 motor weakness of the left EHL and 3/5 of the left tibialis posterior (TP) muscle) and intractable pain radiating down her left leg. Repeat MRI showed a spinal epidural abscess at the level of L4–5 (Figure 4). She was taken to the operating room immediately and the spinal epidural abscess was drained by open surgery. The same antibiotic therapy was continued for 8 weeks post-operatively, and resulted in complete pain relief and improvement in her motor strength to 4/5 for both the EHL and TP muscles. Hypoesthesia was present at the time of discharge and 8 weeks later. Blood and surgical specimens failed to grow Brucella organisms.

Discussion

Osteoarticular complications of brucellosis are common.10 Brucellar spondylitis occurs most commonly in the lumbar region, and may require operative intervention in case of paravertebral and/or epidural mass lesions, spinal cord or radicular compression, or spinal instability.8, 10, 11, 12 Spinal epidural abscess, occurring in 15% of brucellar spondylitis cases, may cause nonspecific clinical and radiological findings.13 As occurred in our patient, initial misdiagnosis of brucellar spondylitis as lumbar disc herniation commonly leads to delays in the initiation of antibiotic therapy. This delay accounts for progression to epidural abscess in a significant proportion of patients.

In brucellosis patients, an average of 3 months passes between the onset of spinal symptoms and visualization of destructive changes on plain films, resulting in low sensitivity and specificity for lumbosacral X-rays to confirm the diagnosis of brucellar spondylitis.7 Computerized tomography of the spine can visualize osseous lesions, the spinal canal, and neural structures.4 As in our patient though, CT images can be nonspecific for Brucella infection, necessitating other diagnostic studies to make a certain diagnosis. Although bone scintigraphy has low specificity for many diseases, it is very sensitive for infectious processes, including osteoarticular complications of brucellosis.14, 15, 16 We utilized bone scan to rule out malignancy and infection, and the positive result helped us focus on ruling out an infectious condition with serological tests.

The most specific diagnostic tool for the evaluation of brucellar spondylitis is MRI.8, 11, 17 Common findings are epiphysitis, narrowing of the disc space, erosion, sclerosis, collapse of the vertebral body, and osteomyelitis. In our patient though, MRI exams were nonspecific until after dramatic progression in pain and neurological deficits, when it showed a spinal epidural abscess.

Unequivocal diagnosis of brucellosis can be achieved by isolating the bacillus from blood, bone marrow, or other tissues. However, detection of this intracellular pathogen by cultures is very difficult and requires special techniques and incubation for 30 days or longer.18 Newly devised radiometric culturing techniques for blood have decreased the isolation time to less than 10 days, but these were not available to our microbiologists. Our patient was typical in that her blood and surgical specimen cultures were all negative. When the cultures are negative, this should not rule out the possibility of spinal brusellosis. The establishment of the diagnosis can be based upon the specific signs, symptoms, and imaging studies in the presence of a high antibody titer.

Currently, the diagnosis of brucellosis with or without spinal involvement is made by detecting serum antibodies with Rose-Bengal, Wright's seroagglutination test, and Coombs' test.19, 20, 21 The Coombs' test becomes positive in the late stages of the disease when antigenic stimulation is high.13 Our patient had a negative Rose-Bengal test at the beginning of her symptoms. As the sensitivity of these tests varies over the course of the disease, one should not rely on just one test when brucellosis is considered in the differential diagnosis. Especially in endemic areas, all three serological tests should be performed in order to avoid false negative results and diagnostic delays.

Epidural mass lesions in the spine may irritate spinal roots and mimic lumbar disc disease.22 If operations are performed without the brucellosis patient being on antibiotics, widespread dissemination of the organism can result.23 Spinal brucellosis cases without fever and fatigue have also been reported in the literature.4, 24 Therefore, especially in areas endemic for brucellosis, spinal surgeons must be very careful to rule out infections such as brucellosis when planning operative therapy for patients with low-back pain and/or sciatica.

Conclusion

Spinal complications of brucellosis can mimic disc disease of the lumbar spine. Nonspecific neurological or radiological findings of this rare condition may lead to diagnostic dilemmas and delays in treatment, allowing further progression of the disease. In endemic areas, brucellosis should be considered and ruled out with serologic tests in patients with sciatica and/or low-back pain.

References

Al-Deeb SM, Yaqub BA, Sharif HS, Phadke JG . Neurobrucellosis: clinical characteristics, diagnosis and outcome. Neurology 1989; 39: 498–501.

Bahemuka M, Shemena AR, Panayiotopoulos CP, Al-Aska AK, Obeid T, Daif AK . Neurological syndromes of brucellosis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatr 1988; 51: 1017–1021.

Basaranoglu M, Mert A, Tabak F, Kanberoǧlu K, Aktuglu Y . A case of cervical brucella spondylitis with paravertebral abscess and neurological deficits. Scand J Infect Dis 1999; 31: 214–215.

Tekkök IH, Berker M, Özcan OE, Özgen T, Akalın E . Brucellosis of the spine. Neurosurgery 1993; 33: 838–844.

Gotuzzo E et al. Articular involvement in human brucellosis: a retrospective analysis of 304 cases. Semin Arthritis Rheum 1982; 12: 245–255.

Zaks N, Suhenik S, Alkan M . Musculoskeletal manifestations of brucellosis: a study of 90 cases in Israel. Semin Arthritis Rheum 1995; 25: 95–97.

Keenan JD, Metz Jr CW . Brucella spondylitis. Clin Orthop 1972; 82: 87–91.

Colmenero JD et al. Clinical course and prognosis of Brucella spondylitis. Infection 1992; 20: 38–42.

Solera J, Lozano E, Martinez-Alfaro E, Espinosa A, Castillejos ML, Abad L . Brucella spondylitis: review of 35 cases and literature survey. Clin Infect Dis 1999; 29: 1440–1449.

Colmenero JD et al. Complications associated with Brucella melitensis infection: a study of 530 cases. Medicine (Baltimore) 1996; 75: 195–211.

Lifeso RM, Harder E, McCorkell SJ . Spinal brucellosis. J Bone Joint Surg Br 1985; 67: 345–351.

Ugarriza LF, Porras LF, Lorenzana LM, Rodriguez-Sanchez JA, Garcia-Yague LM, Cabezudo JM . Brucellar spinal epidural abscesses. Analysis of eleven cases. Br J Neurosurg 2005; 19: 235–240.

Pina MA, Modrego PJ, Uroz JJ, Cobeta JC, Lerin FJ, Baiges JJ . Brucellar spinal epidural abscess of cervical location: report of four cases. Eur Neurol 2001; 45: 249–253.

Cordero-Sanchez M, Alverez-Ruiz S, Lopez Ochoa J, Garcia-Talavera R . Scintigraphic evaluation of lumbosacral pain in brucellosis. Arthritis Rheum 1990; 33: 1052–1055.

Elgazzar AH, Abdel-Dayem HM, Shible O . Brucellosis simulating metastases on Tc 99m MDP bone scan. Clin Nucl Med 1991; 16: 189–191.

Madkour MM, Sharif SS, Abed MY . Osteoarthricular brucellosis: results of bone scintigraphy in 140 patients. Am J Roentgenol 1988; 150: 1101–1105.

Sharif HS, Aideyan OA, Clark DC . Brucellar and tuberculous spondylitis:comparative imaging features. Radiology 1989; 171: 419–425.

Young EJ . An overview of human brucellosis. Clin Infect Dis 1995; 21: 283–290.

Serra J, Vinas M . Laboratory diagnosis of brucellosis in a rural endemic area in northeastern Spain. Int Microbiol 2004; 7: 53–58.

Young EJ . Serologic diagnosis of human brucellosis: analysis of 214 cases by agglutination tests and review of the literature. Rev Infect Dis 1991; 13: 359–372.

Young EJ . Brucella species. In: Mandell GL, Bennett JE, Dolin R (eds). Mandell, Douglas and Bennett's Principles and Practice of Infectious Diseases, 5th edn. Churchill Livingstone: New York 2000, pp 2386–2393.

Özgöçmen S, Yılmaz N, Ardicoglu O, Erdem HR . Brucella disc infection mimicking lumbar disc herniation: a case report. Kaohsiung J Med Sci 1999; 15: 710–714.

Nas K, Gür A, Kemaloǧlu MS . Management of spinal brucellosis and outcome of rehabilitation. Spinal Cord 2001; 39: 223–227.

Mousa AM et al. Neurological complications of brucella spondylitis. Acta Neurol Scand 1990; 81: 16–23.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Yuksel, K., Senoglu, M., Yuksel, M. et al. Brucellar spondylo-discitis with rapidly progressive spinal epidural abscess presenting with sciatica. Spinal Cord 44, 805–808 (2006). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.sc.3101938

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.sc.3101938

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Brucellar spondylodiscitis: comparison of patients with and without abscesses

Rheumatology International (2013)