Abstract

Neuroanatomical and pharmacological evidence implicates glutamate transmission in drug-environment conditioning that partly controls drug seeking and relapse. Glutamate receptors could be targets for pharmacological attenuation of the motivational properties of drug-paired cues and for relapse prevention. The purpose of the present study was therefore to investigate the involvement of ionotropic and metabotropic glutamate receptor subtypes in cue-induced reinstatement of cocaine-seeking behavior. Rats were trained to self-administer cocaine using a second-order schedule of reinforcement (FR4(FR5:S)) under which a compound stimulus (light and tone) associated with cocaine infusions was presented contingently. Following extinction, the effects of the competitive NMDA receptor antagonist CGP 39551 (0, 2.5, 5, 10 mg/kg intraperitoneally (i.p.)), two competitive AMPA/kainate antagonists, CNQX (0, 0.75, 1.5, 3 mg/kg i.p.) and NBQX (0, 1.25, 2.5, 5 mg/kg i.p.), the NMDA/glycine site antagonist L-701,324 (0, 0.63, 1.25, 2.5 mg/kg i.p.), and the mGluR5 antagonist MPEP (0, 1.25, 2.5, 5 mg/kg i.p.) on cue-induced reinstatement of cocaine seeking were examined. The AMPA/kainate receptor antagonists CNQX and NBQX, the NMDA/glycine site antagonist L-701,324, and the mGluR5 antagonist MPEP attenuated significantly cue-induced reinstatement. The NMDA antagonist CGP 39551 failed to affect reinstatement. Additional control experiments indicated that attenuation of cue-induced reinstatement by CNQX, NBQX, L-701,324, and MPEP was not accompanied by significant suppression of spontaneous locomotor activity. These results suggest that conditioned influences on cocaine seeking depend on glutamate transmission. Accordingly, drugs with antagonist properties at various glutamate receptor subtypes could be useful in prevention of relapse induced by conditioned stimuli.

Similar content being viewed by others

INTRODUCTION

Environmental stimuli present during drug taking can acquire incentive-motivational power through classical conditioning. Thereby, they can elicit craving and relapse in abstinent drug users, even after years of abstinence, and thus contribute to the compulsive nature of drug addiction (Carter and Tiffany, 1999). In laboratory animals, cue-induced reinstatement of drug seeking models some aspects of relapse in human addicts, and may have good predictive validity in testing drugs that could decrease the motivational properties of drug-associated cues. Moreover, this model has been demonstrated to be sensitive to manipulation of the limbic cortical–ventral striatopallidal circuits that control drug seeking (Everitt and Wolf, 2002). In the reinstatement model, environmental cues are paired either with drug infusions or with drug availability during self-administration training. After extinction, the power of the drug-associated stimuli to control behavior is revealed by reintroduction of the stimuli, which reinstates responding on the previously active lever.

Both neuroanatomical and pharmacological evidence suggests that glutamate transmission is involved in the conditioning processes underlying drug seeking. Neuroimaging studies in abstinent drug users demonstrated that the nucleus accumbens, and regions of the prefrontal cortex and the amygdala that send convergent glutamatergic projections to the nucleus accumbens, were all activated by cocaine-associated cues that induced subjective feelings of craving (Grant et al, 1996; Kilts et al, 2001). Similarly, exposure to cocaine self-administration environment enhanced Fos protein expression, a marker of neuronal activation, in these brain regions in rats (Neisewander et al, 2000). In accordance with these findings, animal studies showed that inactivation of regions of the nucleus accumbens, prefrontal cortex, and amygdala attenuated the ability of drug-associated cues to trigger drug-seeking behavior (McLaughlin and See, 2003; Fuchs et al, 2004). Conversely, electrical or pharmacological stimulation of these anatomical sites induced drug seeking in rats (Cornish and Kalivas, 2000; McFarland and Kalivas, 2001; Hayes et al, 2003).

The nucleus accumbens has a central role in controlling stimulus-reward associations, and one of the key neurotransmitters is dopamine (Di Chiara et al, 1999; Weiss et al, 2000). However, there are many lines of evidence showing that the nucleus accumbens glutamate transmission also contributes to the associative mechanisms controlling drug seeking. For example, discrete cocaine-associated stimuli increased nucleus accumbens glutamate levels in rats (Hotsenpiller et al, 2001). In line with this finding, both AMPA and NMDA type glutamate agonists injected into the nucleus accumbens reinstated extinguished cocaine seeking (Cornish et al, 1999). In contrast, both reinstatement of cocaine seeking induced by cocaine priming and cocaine seeking under a second-order schedule of reinforcement were attenuated by an intra-accumbal AMPA/kainate receptor antagonist injection (Cornish and Kalivas, 2000; Di Ciano and Everitt, 2001).

Supporting the contribution of AMPA/kainate receptors in cocaine-environment conditioning, AMPA/kainate receptor antagonists have been reported to diminish cocaine-conditioned locomotion, cocaine-induced place preference, and cocaine seeking under a second-order schedule of reinforcement (Cervo and Samanin, 1995; Jackson et al, 1998; Bäckström and Hyytiä, 2003), whereas evidence for the involvement of NMDA receptors in cocaine-seeking behavior is less consistent (De Vries et al, 1998; Kotlinska and Biala, 2000). In addition to the suggested role of ionotropic AMPA/kainate and NMDA glutamate receptors in conditioned influences on drug seeking, evidence is accumulating that the metabotropic glutamate receptors (mGluRs) may also be implicated. mGluRs are G protein-coupled receptors that are classified into three main groups (groups I–III), including eight subtypes (mGluR1–8) (Schoepp, 2001). The mGluR2/3 agonist LY379268 was reported to attenuate cue-induced cocaine seeking in rats (Baptista et al, 2004), and the mGluR5 antagonist MPEP decreased conditioned place preference to morphine and cocaine and cue-induced alcohol-seeking behavior (Popik and Wrobel, 2002; McGeehan and Olive, 2003; Bäckström et al, 2004).

The importance of the glutamate receptor subtypes in cocaine-seeking behavior has not been systematically explored. Therefore, the purpose of the present study was to investigate the effects of various ionotropic and mGluR antagonists on cocaine seeking using the cue-induced reinstatement model. During cocaine self-administration training and reinstatement, we used a second-order schedule of reinforcement because second-order schedules have been suggested to facilitate the development of response-outcome associations and amplify the significance of the conditioned stimuli in maintaining responding (Everitt and Robbins, 2000). Thus, robust reinstatement of responding by drug-paired stimuli has been observed following training under such schedules (Arroyo et al, 1998; Kantak et al, 2002). The ionotropic glutamate antagonists included the competitive NMDA receptor antagonist CGP 39551, the competitive AMPA/kainate antagonists CNQX and NBQX, and the NMDA/glycine site antagonist L-701,324. CNQX has also activity at the glycine binding site on the NMDA receptors, whereas NBQX is a more selective AMPA/kainate antagonist (Sheardown et al, 1990). The mGluR5 antagonist MPEP was chosen to represent the mGluR antagonists, because it has previously been shown to antagonize many drug-related behaviors.

METHODS

Animals

Male Wistar rats (HsdCpb:Wu, Harlan, The Netherlands) weighing 180–200 g upon arrival were housed in pairs in Eurostandard Type IV cages (transparent polycarbonate, dimensions 595 × 380 × 200 mm3) in a temperature and humidity controlled room under a reversed 12-h light–dark cycle (lights off at 0600). Water and pellet food (RM1, SDS, Witham, UK) were available ad libitum in the home cage except during food training (see subsequent description). All behavioral testing was carried out during the dark phase of the light–dark cycle between 0800 and 1400, 5 days a week. All experimental procedures using animals were carried out in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the National Public Health Institute and the Chief Veterinarian of the County Administrative Board.

Drugs

CGP 39551, L-701,324, CNQX, NBQX and MPEP were obtained from Tocris Cookson Ltd (Bristol, UK). CGP 39551 was dissolved in saline. L-701,324 and MPEP were suspended in propylene glycol, Tween-80, and saline (ratio 1 : 1 : 18). CNQX and NBQX were dissolved in distilled water. All drugs were administered i.p. in a volume of 1 ml/kg.

Apparatus

Self-administration experiments took place in operant chambers (Model ENV-112B, MED Associates, Georgia, VT, USA) enclosed in ventilated sound-attenuating cubicles. For self-administration training with food, the chambers were equipped with a food hopper in the middle of the front panel. A food dispenser located behind the front panel delivered 45-mg Noyes pellets to the food hopper. Two retractable levers were located on both sides of the food hopper. A white stimulus light was mounted above each lever. Auditory stimuli were delivered from a speaker positioned on the front panel. Intravenous infusions were delivered at the volume of 0.1 ml by activating an infusion pump outside the sound-attenuating cubicle. The infusion pump was attached to a counterbalanced liquid swivel with Tygon tubing. From the swivel, Tygon tubing protected by a steel spring passed through a hole in the operant chamber and was connected to the catheter base at the midscapular region of the animal. A computer using MED-PC behavioral software (MED Associates) controlled schedule contingencies and data collection.

Surgery

Rats were anesthetized with an isoflurane–air mixture and implanted with a chronic jugular catheter, as described previously (Caine et al, 1993). Briefly, the catheter assembly made in-house consisted of a 13-cm length of silastic tubing (inside diameter 0.31 mm; outside diameter 0.64 mm), attached to a guide cannula that was bent at a right angle. The cannula was embedded into a dental cement base and anchored with surgical polypropylene mesh. The catheters were implanted with the proximal end reaching the heart through the right jugular vein, continuing subcutaneously over the shoulder, and exiting between the scapulae. After surgery, catheters were flushed once a day for the next 10 days with a 0.05 ml infusion of an antibiotic (Oriprim, Orion Pharma, Espoo, Finland) to prevent infection and a 0.1 ml infusion of 0.9% saline containing heparin (30 IU/ml). Thereafter, the catheters were flushed daily with heparinized saline at the end of each self-administration session. If an abrupt increase or decrease was observed in the number of cocaine infusions earned by an individual animal during a session, catheter patency was tested by infusing the short-acting anesthetic methohexital (Brietal, Eli Lilly and Co., Indianapolis, IN, USA) through the catheter. Animals with patent catheters exhibited a rapid loss of muscle tone within 2 s of the methohexital infusion. In the present study, 4% of catheters lost patency during the self-administration phase.

Food Training

To facilitate acquisition of cocaine self-administration, rats were trained to lever press for food reinforcement before catheter implantation. During training, rats were restricted to 4 g of standard pellet food per day, and trained to respond for a delivery of a 45-mg Noyes pellet under a fixed ratio 1 (FR1) schedule with a time-out (TO) duration of 1 s on both response levers until they earned 100 pellets during the 60-min session. Once rats had reached this criterion (2–4 sessions), they were returned to ad libitum food and implanted with i.v. catheters. The cocaine-paired stimulus complex (see below) was not presented during food training.

Cocaine Self-Administration: Conditioning and Extinction Phases

At 1 week after surgery, rats were allowed to respond for a 0.1 ml infusion of cocaine (0.25 mg/infusion, dissolved in 0.9% physiological saline) under an FR1 TO 20-s schedule during daily 2-h sessions. At the beginning of each session, the house light was turned off and the two response levers were extended. Responding on the active lever resulted in an infusion that was signaled by a 20-s illumination of the stimulus light and a 3.5-s tone. Responses on the inactive lever were recorded but had no programmed consequences. Once animals had acquired reliable responding under the FR1 TO 20-s schedule, a second-order schedule of reinforcement of the type FRx(FRy:S) was introduced, where x was the number of conditioned stimulus (CS) presentations (1-s stimulus light and tone) required for the delivery of a cocaine infusion and y was the number of lever presses required for each CS presentation. Therefore, rats were presented a 1-s stimulus light and tone after y responses, and a 20-s stimulus light and a 3.5-s tone after completion of x, that is, during each cocaine infusion. The schedule requirements were gradually increased as follows: FR1(FR2:S), FR1(FR3:S), FR1(FR5:S), FR1(FR7:S), FR2(FR5:S), FR3(FR5:S), FR4(FR5:S).

Extinction training began after 4–6 days of cocaine self-administration under the FR4(FR5:S) schedule. During the extinction phase, responding had no programmed consequences. Extinction sessions continued until no further trend for either increased or decreased responding was seen in the group mean for at least five consecutive sessions.

Cue-Induced Reinstatement of Cocaine-Seeking Behavior

Reinstatement testing began on day 1 postextinction. During the first minute of the 2-h reinstatement session, the CS was presented six times noncontingently (once every 10 s) (Arroyo et al, 1998). Then the response levers were extended into the operant chamber and the cocaine-associated stimulus (CS) complex was contingently available under the FR4(FR5:S) schedule that was used during the conditioning phase, but no cocaine was available. Reinstatement sessions were conducted twice a week, with at least two intervening days during which the rats remained in their home cages.

Persistent cue-induced reinstatement of cocaine seeking has previously been shown across multiple tests that were not separated by extinction sessions (Weiss et al, 2001; Kantak et al, 2002). However, in order to exclude the possibility that responding during reinstatement sessions was induced by the testing schedule and not by presentation of the CS, a group of rats (n=7) with reliable reinstatement baselines was tested during seven consecutive twice-a-week reinstatement sessions under extinction conditions.

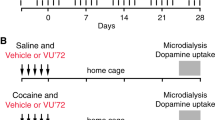

Experiment 1: Effects of Glutamate Receptor Antagonism on Cocaine-Seeking Behavior

A total of three cohorts, each consisting of 16 rats were trained for the experiments. Assignment of rats to drug treatment groups was random, except that only rats that showed stable performance both during cocaine self-administration sessions and three baseline reinstatement sessions with saline pretreatment (1 ml/kg intraperitoneally (i.p.) 20 min before testing) were included in the experiments. Stable self-administration was defined as less than 15% variation in the mean number of infusions over four days. For reinstatement sessions, responding was considered stable when the number of responses showed no trend towards an increase or decrease and the variation was less than 25% over three consecutive sessions.

The effects of the NMDA antagonist CGP 39551 (0, 2.5, 5, 10 mg/kg, n=8), the NMDA/glycine antagonist L-701,324 (0, 0.63, 1.25, 2.5 mg/kg, n=10), the AMPA/kainate antagonists CNQX (0, 0.75, 1.5, 3 mg/kg, n=8) and NBQX (0, 1.25, 2.5, 5 mg/kg, n=7), and the mGluR5 antagonist MPEP (0, 1.25, 2.5, 5 mg/kg, n=10) on cue-induced reinstatement of cocaine seeking were examined. The drugs were administered i.p. 20 min before behavioral testing in a within-subjects Latin square design.

Experiment 2: Effects of Glutamate Receptor Antagonism on Spontaneous Locomotor Activity

To clarify whether the changes in reinstatement responding observed after pretreatment with glutamate receptor antagonists were caused by effects on motor performance, spontaneous locomotor activity was measured after antagonist pretreatment.

Locomotor activity was measured in transparent Eurostandard Type III cages (transparent polycarbonate, dimensions 18 × 33 × 15 cm3) that were placed inside photocell frames (Cage Rack Activity System, San Diego Instruments, CA, USA). The frames were equipped with seven pairs of photocells (5 cm off the cage floor) for measuring horizontal activity and eight pairs of photocells (12 cm off the floor) for measuring vertical activity. The number of photocell interruptions was recorded by a computer at 5-min intervals for 2 h. During the first three sessions, rats were habituated to the test cages, and, on the third day, also administered with a habituation saline injection (1 ml/kg, i.p.). Thereafter, testing sessions were carried out twice a week. Glutamate antagonists CGP 39551, L-701,324, CNQX, NBQX, and MPEP (n=8 for each drug, doses as above) were injected i.p. in a within-subjects Latin square design 20 min before testing.

Statistical Analysis

During each operant session, the following data were recorded: the total number of active and inactive lever responses, the latency to initiate responding, the latency to the first CS presentation, inter-infusion intervals (for self-administration sessions), and inter-response intervals (for extinction and reinstatement sessions).

In order to confirm reinstatement of responding by the CS after extinction, the mean number of active and inactive lever responses over a 3-day extinction baseline was compared to the mean number of responses emitted during the first reinstatement session using a paired t-test. The stability of reinstatement responding across the repeated drug injections included in the Latin square was demonstrated by comparing the 0 mg/kg injection with the mean of three vehicle injection sessions preceding drug pretreatment with paired t-tests.

The significance of the CS in maintaining responding during reinstatement sessions conducted twice a week was shown by comparing responding during the seven consecutive extinction sessions (twice a week) with a 3-day reinstatement baseline using a within-subjects one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with repeated measures on session, followed by individual comparisons between extinction sessions and the reinstatement baseline.

In the reinstatement experiments, ANOVA indicated that there were significant differences in the baseline number of active lever responses between groups assigned to different drug treatments (F(4,38)=4.91, p<0.01). Therefore, responding on the active lever during drug pretreatment sessions was expressed as a percentage of the mean number of responses during three vehicle injection sessions that preceded drug pretreatment sessions. The effects of glutamate receptor antagonists on cocaine seeking and locomotor activity were analyzed with a within-subjects one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with repeated measures on dose. Following a significant main effect of dose, each individual drug dose was compared with the 0 mg/kg condition using a post hoc means comparison with Bonferroni correction. In all statistical analyses, criterion for significance was set at the 0.05 level.

RESULTS

Conditioning, Extinction and Reinstatement

Rats reached the FR4(FR5:S) schedule of cocaine self-administration in approximately 7 weeks. For all subjects included in the final data analysis, the mean (±SEM) number of responses averaged over the last three sessions was 409.0±29.4 on the active and 10.0±7.0 on the inactive lever. Under extinction conditions, rats reached the extinction criteria within 15 sessions. The mean (±SEM) number of responses over the last three extinction sessions (later referred to as extinction baseline) was 14.8±1.3 on the previously active lever and 4.7±0.8 on the previously inactive lever.

Reintroduction of the CS reinstated responding selectively on the active lever (mean±SEM number of responses 74.8±10.7, p<0.05 compared to extinction baseline), with no effects on inactive lever responses. The levels of reinstated responding were clearly lower than those during cocaine self-administration, during which responding was maintained by both the CS and the reinforcing effects of cocaine. Across repeated test sessions conducted twice per week, responding was maintained reliably above the extinction baseline. Figure 1 demonstrates that when the CS was omitted in a separate group of subjects, responding decreased rapidly to 14% of the baseline level over the seven consecutive extinction sessions (F(7,42)=15.12, p<0.0001), suggesting that the CS had a major role in maintenance of reinstatement responding. Responding was significantly decreased from the first extinction session.

Effect of omission of the CS on reinstatement responding. Shown is the mean (±SEM) number of active lever responses during the reinstatement baseline (‘Reinst’) and seven consecutive extinction sessions, conducted on every second or third day. During the extinction sessions, the cocaine-associated CS was not presented. *p<0.05, significantly different from the reinstatement baseline.

Experiment 1: Effects of Glutamate Receptor Antagonism on Cocaine-Seeking Behavior

With all ionotropic glutamate receptor antagonists, responding during reinstatement sessions remained stable during the period of testing as confirmed by paired t-tests conducted separately for each antagonist between the 0 mg/kg dose and a 3-day reinstatement baseline (responding averaged over three saline pretreatment sessions preceding drug treatments) (p's>0.05). However, in the MPEP treatment group, responding during the 0 mg/kg session was decreased compared to baseline reinstatement sessions (p<0.05). Paired t-tests comparing the 0 mg/kg session with the extinction baseline indicated significant reinstatement of responding in all antagonist groups (p's<0.05). The mean (±SEM) number of responses during the baseline reinstatement sessions for the treatment groups were as follows: CGP 39551, 62±13; L-701,324, 107±14; CNQX, 56±7; NBQX, 121±21; and MPEP 115±21.

Figure 2 shows the effects of glutamate receptor antagonism on cue-induced cocaine seeking. The NMDA/glycine antagonist L-701,324 (F(3,27)=9.46, p<0.001), the AMPA/kainate antagonists CNQX (F(3,21)=5.87, p<0.01) and NBQX (F(3,18)=9.53, p<0.001), and the mGluR5 antagonist MPEP (F(3,27)=13.26, p<0.0001) decreased significantly responding for the CS complex. In contrast, the NMDA antagonist CGP 39551 failed to affect responding (F(3,21)=0.27, NS). Inactive lever responding (data not shown) was not affected by antagonist pretreatment, with the exception of MPEP that decreased responding also on the inactive lever (F(3,27)=3.59, p<0.05).

Effects of pretreatment with CGP 39551 (n=8), L-701,324 (n=10), CNQX (n=8), NBQX (n=7), and MPEP (n=10) on CS-induced reinstatement responding during the 2-h session. Responses are expressed as the percentage (mean±SEM) of the mean number of responses during three vehicle injection sessions that preceded the drug pretreatment sessions. *p<0.05, significantly different from the vehicle condition.

Cumulative response patterns shown in Figure 3 indicate that rats responded at stable rates throughout the 2-h sessions. The response-attenuating effects of L-701,324, CNQX and NBQX emerged gradually during the session, whereas MPEP pretreatment tended to suppress the initiation of responding during the first 40 min of the session. Response patterns of individual rats were characterized by bursts of responding, often in stacks of five to 10 responses reflecting the response requirement for the CS, and followed by a period of no responding after the CS presentation (data not shown). Pretreatment with glutamate receptor antagonists did not disrupt the pattern of responding but increased the intervals between bursts and decreased the number of responses in a burst.

Analysis of the latencies to the first CS under the FR4(FR5:S) reinstatement schedule revealed that the latency was increased by L-701,324 (F(3,27)=3.07, p<0.05), although this effect was not detected by the post hoc test, and the highest dose of MPEP (F(3,27)=10.02, p<0.001) (data not shown). Latencies were not altered by the other pretreatments. Also, the latencies to emit the first response did not differ from the saline condition with any of the antagonists tested (data not shown).

Experiment 2: Effects of Glutamate Receptor Antagonism on Spontaneous Locomotor Activity

Although CGP39551 tended to decrease and L-701,324 and MPEP tended to increase spontaneous ambulatory activity, these effects did not reach significance (Figure 4). Vertical activity was decreased only by CGP39551 (F(3,12)=3.08, p<0.05), but this effect was not significant in the Bonferroni post hoc test.

DISCUSSION

In the present study, we examined the involvement of glutamate receptors in cue-induced reinstatement of cocaine seeking. The subjects were trained to self-administer cocaine using a second-order schedule of reinforcement under which a compound stimulus (light and tone) associated with cocaine infusions was presented contingently. After extinction, noncontingent presentations of the CS, followed by contingent access to the CS, reinstated and maintained responding above the extinction baseline at a level that was not diminished during the period of pharmacological testing. The significance of the CS in maintaining responding was verified further in a separate test, in which omission of the CS caused a rapid extinction of responding. Moreover, the importance of these stimuli in exerting control over behavior could be seen in the individual response patterns of rats, which were characterized by bursts of responding, often corresponding to the number of responses required for a stimulus presentation, and followed by a period with no responding. These results are in accordance with previous studies showing that cocaine-paired stimuli can reinstate extinguished cocaine-seeking behavior (Meil and See, 1996; Arroyo et al, 1998; Alleweireldt et al, 2002).

Responding for the CS was decreased by pretreatment with the NMDA/glycine site antagonist L-701,324, the AMPA/kainate antagonists CNQX and NBQX, and the mGluR5 antagonist MPEP. In contrast, the competitive NMDA antagonist CGP 39551 did not modify reinstatement responding. Reductions by L-701,324, CNQX and NBQX were not accompanied by delayed initiation of responding or decreased number of inactive lever responses. Cumulative response patterns showed that rats responded at a stable level throughout the session, and the effects of antagonist pretreatments became visible slowly during the session. These findings suggested that the observed decreases were not due to nonspecific effects by the antagonists. In order to analyze further the possible nonspecific effects, we examined the effects of all antagonists on spontaneous locomotor activity. These tests indicated that effects on locomotion and reinstatement responding could be dissociated: the NMDA antagonist CGP 39551 decreased vertical activity with no effects on reinstatement responding, whereas antagonists that attenuated cue-induced reinstatement, L-701,324, CNQX, NBQX, and MPEP, tended to increase ambulation. Together, these data suggest that generalized disruption of motor function most likely did not contribute to decreased reinstatement. These findings are in agreement with previous data on the effects of these drugs on locomotion (Dalia and Wallace, 1995; Bristow et al, 1996; Mead and Stephens, 1999; Ossowska et al, 2001). Measurement of spontaneous locomotor activity may, however, have only limited value as control of drug-induced changes in reinstatement behavior, because habituated animals have relatively low basal activity levels. Moreover, it is possible that the effects of glutamate antagonists in naïve rats could differ from those in cocaine-experienced rats.

The present results parallel our earlier findings that systemically administered CNQX and L-701,324, but not CGP 39551, attenuated cue-induced reinstatement of alcohol-seeking behavior (Bäckström and Hyytiä, 2004). In addition, CNQX attenuated cocaine seeking during the first 15-min interval under an FI 15 min (FR7:S) second-order schedule with no effects on cocaine self-administration (Bäckström and Hyytiä, 2003). AMPA and NMDA receptor antagonists have been shown to attenuate also the expression of other conditioned and drug-related behaviors. For example, AMPA antagonists such as CNQX, DNQX, NBQX, and GYKI52466 reduced the expression of conditioned place preference and behavioral sensitization (Cervo and Samanin, 1995; Tzschentke and Schmidt, 1997; Jackson et al, 1998; Mead and Stephens, 1998, 1999; but see Li et al, 1997). NMDA antagonists, however, seem to differ in their ability to modulate these behaviors. The channel-blocker memantine and the competitive antagonist CPP were capable of blocking the expression of place preference to several drugs (Bespalov, 1996; Kotlinska and Biala, 2000; Popik et al, 2003), whereas the effects by ACPC, a partial agonist of the glycine site on the NMDA receptors (a functional NMDA antagonist), and by the NMDA/glycine antagonist L-701,324 were mixed (Kotlinska and Biala, 1999; Mead and Stephens, 1999; Kotlinska and Biala, 2000; Papp et al, 2002). In the present study, the lack of effects on reinstatement by CGP 39551 could not be explained by insufficient dosing, because it affected motor behavior and the dose range used has previously been reported to produce behavioral effects (De Sarro et al, 1996; Kosowski et al, 2004). However, we cannot dismiss the role of the NMDA receptor complex in cue-induced reinstatement because functional NMDA antagonism by the NMDA/glycine antagonist attenuated reinstatement.

In this study, the pattern of suppression of cue-induced reinstatement of cocaine seeking by the mGluR5 antagonist MPEP differed from that by the other glutamate receptor antagonists tested. MPEP doses that affected active lever responses decreased also inactive lever responding significantly, and reduction of lever pressing was accompanied by an increase in the latency to obtain the first stimulus presentation. Therefore, MPEP pretreatment effectively suppressed responding during the first 40 min of the session, as shown by the cumulative response pattern. However, it would be very difficult to explain these effects by motor impairment, because MPEP tended to increase ambulatory locomotor activity. This finding is in agreement with previous reports, showing no decrease in spontaneous locomotion by the MPEP dose range used here (Ossowska et al, 2001; Henry et al, 2002). Unlike the other subjects, the group of rats given MPEP injections also decreased their reinstatement baseline during injections, suggesting that MPEP might have had long-term effects on this behavior. MPEP has previously been shown to modulate a wide variety of drug-related behaviors. MPEP reduced cocaine, nicotine, and ethanol self-administration, as well as cocaine and nicotine seeking induced by a priming injection (Sharko et al, 2002; Paterson et al, 2003; Tessari et al, 2004; Lee et al, 2005). In addition, MPEP was shown to attenuate conditioned drug effects, such as morphine- and cocaine-induced place preference and cue-induced ethanol seeking (Popik and Wrobel, 2002; McGeehan and Olive, 2003; Bäckström et al, 2004). In contrast to decreases produced by MPEP on both drug-seeking and drug-taking behavior, the AMPA/kainate antagonist CNQX attenuated cocaine seeking under a second-order schedule with no effects on cocaine self-administration (Bäckström and Hyytiä, 2003). Similarly, the doses of the NMDA/glycine antagonist L-701,324 that suppressed cue-induced reinstatement of cocaine seeking in the present study did not modulate cocaine self-administration (Hyytiä et al, 1999). These data suggest that the mGluR5 antagonist MPEP may have qualitatively different effects on cocaine-related behaviors compared with glutamate antagonists acting at the ionotropic receptors.

Our results are compatible with the hypothesis that environmental stimuli can acquire control over drug-seeking behavior in a glutamate-dependent manner. Pharmacological blockade of glutamate receptors by systematically administered antagonists leading to attenuation of cue-induced reinstatement does not reveal any specific neuroanatomical systems through which glutamate transmission may control drug seeking. Previous work has elegantly demonstrated the involvement of the limbic cortical–ventral striatopallidal systems in conditioned drug seeking (Everitt and Wolf, 2002). Glutamatergic projections from the prefrontal cortex, amygdala, and hippocampus may interact at the level of the nucleus accumbens in a way that facilitates dopamine release (Blaha et al, 1997; Floresco et al, 1998). Interestingly, exposure to discrete stimuli paired repeatedly with cocaine increased extracellular glutamate release in the nucleus accumbens, and this increase occurred against a reduced basal glutamate level (Hotsenpiller et al, 2001). These findings indicate that conditioned processes have clear effects on glutamate transmission. It is possible that one of the factors precipitating relapse could be cue-induced glutamate release in the nucleus accumbens, and that ionotropic glutamate receptor antagonism could attenuate cue-induced reinstatement by blunting the accumbal glutamate transmission postsynaptically. There is evidence that in addition to its postsynaptic actions, the mGluR5 antagonist MPEP could also inhibit glutamate release presynaptically (Thomas et al, 2001), which may explain partly the modulation of the wide range of drug-related behaviors by MPEP.

In summary, we showed that contingently delivered cues associated with cocaine infusions under a second-order schedule of reinforcement during self-administration training reliably reinstated active lever responding after extinction. Systemic administration of the AMPA/kainate receptor antagonists CNQX and NBQX, the NMDA/glycine site antagonist L-701,324, and the mGluR5 antagonist MPEP attenuated significantly cue-induced reinstatement, but the NMDA antagonist CGP 39551 had no effect. Measurement of spontaneous locomotor activity after glutamate antagonist administration indicated that significant decreases in reinstatement could not be attributed to a general suppression of behavior. Our results extend the body of evidence implicating glutamate transmission in conditioned influences on cocaine seeking and suggest that various glutamate receptors may be promising targets for pharmacological treatment of relapse.

References

Alleweireldt AT, Weber SM, Kirschner KF, Bullock BL, Neisewander JL (2002). Blockade or stimulation of D1 dopamine receptors attenuates cue reinstatement of extinguished cocaine-seeking behavior in rats. Psychopharmacology 159: 284–293.

Arroyo M, Markou A, Robbins TW, Everitt BJ (1998). Acquisition, maintenance and reinstatement of intravenous cocaine self-administration under a second-order schedule of reinforcement in rat: effects of conditioned cues and continuous access to cocaine. Psychopharmacology 140: 331–344.

Baptista MA, Martin-Fardon R, Weiss F (2004). Preferential effects of the metabotropic glutamate 2/3 receptor agonist LY379268 on conditioned reinstatement versus primary reinforcement: comparison between cocaine and a potent conventional reinforcer. J Neurosci 24: 4723–4727.

Bespalov A (1996). The expression of both amphetamine-conditioned place preference and pentylenetetrazol-conditioned place aversion is attenuated by the NMDA receptor antagonist (+/−)-CPP. Drug Alcocol Depend 41: 85–88.

Blaha CD, Yang CR, Floresco SB, Barr AM, Phillips AG (1997). Stimulation of the ventral subiculum of the hippocampus evokes glutamate receptor-mediated changes in dopamine efflux in the rat nucleus accumbens. Eur J Neurosci 9: 902–911.

Bristow LJ, Flatman KL, Hutson PH, Kulagowski JJ, Leeson PD, Young L et al (1996). The atypical neuroleptic profile of the glycine/N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor antagonist, L-701,324, in rodents. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 277: 578–585.

Bäckström P, Bachteler D, Koch S, Hyytiä P, Spanagel R (2004). mGluR5 antagonist MPEP reduces ethanol-seeking and relapse behavior. Neuropsychopharmacology 29: 921–928.

Bäckström P, Hyytiä P (2003). Attenuation of cocaine-seeking behaviour by the AMPA/kainate receptor antagonist CNQX in rats. Psychopharmacology 166: 69–76.

Bäckström P, Hyytiä P (2004). Ionotropic glutamate receptor antagonists modulate cue-induced reinstatement of ethanol-seeking behavior. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 28: 558–565.

Caine SB, Lintz R, Koob GF (1993). Intravenous drug self-administration techniques in animals. In: Sahgal A (ed). Behavioral Neuroscience: A Practical Approach. University Press: Oxford. pp 117–143.

Carter BL, Tiffany ST (1999). Meta-analysis of cue-reactivity in addiction research. Addiction 94: 327–340.

Cervo L, Samanin R (1995). Effects of dopaminergic and glutamatergic receptor antagonists on the acquisition and expression of cocaine conditioning place preference. Brain Res 673: 242–250.

Cornish JL, Duffy P, Kalivas PW (1999). A role for nucleus accumbens glutamate transmission in the relapse to cocaine-seeking behavior. Neuroscience 93: 1359–1367.

Cornish JL, Kalivas PW (2000). Glutamate transmission in the nucleus accumbens mediates relapse in cocaine addiction. J Neurosci 20: 1–5.

Dalia A, Wallace LJ (1995). Amphetamine induction of c-fos in the nucleus accumbens is not inhibited by glutamate antagonists. Brain Res 694: 299–307.

De Sarro G, De Sarro A, Ammendola D, Patel S (1996). Lack of development of tolerance to anticonvulsant effects of two excitatory amino acid antagonists, CGP 37849 and CGP 39551 in genetically epilepsy-prone rats. Brain Res 734: 91–97.

De Vries TJ, Schoffelmeer ANM, Binnekade R, Mulder AH, Vanderschuren LJMJ (1998). MK-801 reinstates drug-seeking behaviour in cocaine-trained rats. NeuroReport 9: 637–640.

Di Chiara G, Tanda G, Bassareo V, Pontieri F, Acquas E, Fenu S et al (1999). Drug addiction as a disorder of associative learning. Role of nucleus accumbens shell/extended amygdala dopamine. Ann NY Acad Sci 877: 461–485.

Di Ciano P, Everitt BJ (2001). Dissociable effects of antagonism of NMDA and AMPA/KA receptors in the nucleus accumbens core and shell on cocaine-seeking behavior. Neuropsychopharmacology 25: 341–360.

Everitt BJ, Robbins TW (2000). Second-order schedules of drug reinforcement in rats and monkeys: measurement of reinforcing efficacy and drug-seeking behaviour. Psychopharmacology 153: 17–30.

Everitt BJ, Wolf ME (2002). Psychomotor stimulant addiction: a neural systems perspective. J Neurosci 22: 3312–3320.

Floresco SB, Yang CR, Phillips AG, Blaha CD (1998). Basolateral amygdala stimulation evokes glutamate receptor-dependent dopamine efflux in the nucleus accumbens of the anaesthetized rat. Eur J Neurosci 10: 1241–1251.

Fuchs RA, Evans KA, Parker MC, See RE (2004). Differential involvement of the core and shell subregions of the nucleus accumbens in conditioned cue-induced reinstatement of cocaine seeking in rats. Psychopharmacology 176: 459–465.

Grant S, London ED, Newlin DB, Villemagne VL, Liu X, Contoreggi C et al (1996). Activation of memory circuits during cue-elicited cocaine craving. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 93: 12040–12045.

Hayes RJ, Vorel SR, Spector J, Liu X, Gardner EL (2003). Electrical and chemical stimulation of the basolateral complex of the amygdala reinstates cocaine-seeking behavior in the rat. Psychopharmacology 168: 75–83.

Henry SA, Lehmann-Masten V, Gasparini F, Geyer MA, Markou A (2002). The mGluR5 antagonist MPEP, but not the mGluR2/3 agonist LY314582, augments PCP effects on prepulse inhibition and locomotor activity. Neuropharmacology 43: 1199–1209.

Hotsenpiller G, Giorgetti M, Wolf ME (2001). Alterations in behaviour and glutamate transmission following presentation of stimuli previously associated with cocaine exposure. Eur J Neurosci 14: 1843–1855.

Hyytiä P, Bäckström P, Liljequist S (1999). Site-specific NMDA receptor antagonists produce differential effects on cocaine self-administration in rats. Eur J Pharmacol 378: 9–16.

Jackson A, Mead AN, Rocha BA, Stephens DN (1998). AMPA receptors and motivation for drug: effect of the selective antagonist NBQX on behavioural sensitization and on self-administration in mice. Behav Pharmacol 9: 457–467.

Kantak KM, Black Y, Valencia E, Green-Jordan K, Eichenbaum HB (2002). Dissociable effects of lidocaine inactivation of the rostral and caudal basolateral amygdala on the maintenance and reinstatement of cocaine-seeking behavior in rats. J Neurosci 22: 1126–1136.

Kilts CD, Schweitzer JB, Quinn CK, Gross RE, Faber TL, Muhammad F et al (2001). Neural activity related to drug craving in cocaine addiction. Arch Gen Psychiatry 58: 334–341.

Kosowski AR, Cebers G, Cebere A, Swanhagen AC, Liljequist S (2004). Nicotine-induced dopamine release in the nucleus accumbens is inhibited by the novel AMPA antagonist ZK200775 and the NMDA antagonist CGP39551. Psychopharmacology 175: 114–123.

Kotlinska J, Biala G (1999). Effects of the NMDA/glycine receptor antagonist, L-701,324, on morphine- and cocaine-induced place preference. Pol J Pharmacol 51: 323–330.

Kotlinska J, Biala G (2000). Memantine and ACPC affect conditioned place preference induced by cocaine in rats. Pol J Pharmacol 52: 179–185.

Lee B, Platt DM, Rowlett JK, Adewale AS, Spealman RD (2005). Attenuation of behavioral effects of cocaine by the metabotropic glutamate receptor 5 antagonist 2-methyl-6-(phenylethynyl)-pyridine in squirrel monkeys: comparison with dizocilpine. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 312: 1232–1240.

Li Y, Vartanian AJ, White FJ, Xue CJ, Wolf ME (1997). Effects of the AMPA receptor antagonist NBQX on the development and expression of behavioral sensitization to cocaine and amphetamine. Psychopharmacology 134: 266–276.

McFarland K, Kalivas PW (2001). The circuitry mediating cocaine-induced reinstatement of drug-seeking behavior. J Neurosci 21: 8655–8663.

McGeehan AJ, Olive MF (2003). The mGluR5 antagonist MPEP reduces the conditioned rewarding effects of cocaine but not other drugs of abuse. Synapse 47: 240–242.

McLaughlin J, See RE (2003). Selective inactivation of the dorsomedial prefrontal cortex and the basolateral amygdala attenuates conditioned-cued reinstatement of extinguished cocaine-seeking behavior in rats. Psychopharmacology 168: 57–65.

Mead AN, Stephens DN (1998). AMPA-receptors are involved in the expression of amphetamine-induced behavioural sensitisation, but not in the expression of amphetamine-induced conditioned activity in mice. Neuropharmacology 37: 1131–1138.

Mead AN, Stephens DN (1999). CNQX but not NBQX prevents expression of amphetamine-induced place preference conditioning: a role for the glycine site of the NMDA receptor, but not AMPA receptors. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 290: 9–15.

Meil WM, See RE (1996). Conditioned cued recovery of responding following prolonged withdrawal from self-administered cocaine in rats: an animal model of relapse. Behav Pharmacol 7: 754–763.

Neisewander JL, Baker DA, Fuchs RA, Tran-Nguyen LTL, Palmer A, Marshall JF (2000). Fos protein expression and cocaine-seeking behavior in rats after exposure to a cocaine-self-administration environment. J Neurosci 20: 798–805.

Ossowska K, Konieczny J, Wolfarth S, Wieronska J, Pilc A (2001). Blockade of the metabotropic glutamate receptor subtype 5 (mGluR5) produces antiparkinsonian-like effects in rats. Neuropharmacology 41: 413–420.

Papp M, Gruca P, Willner P (2002). Selective blockade of drug-induced place preference conditioning by ACPC, a functional NDMA-receptor antagonist. Neuropsychopharmacology 27: 727–743.

Paterson NE, Semenova S, Gasparini F, Markou A (2003). The mGluR5 antagonist MPEP decreased nicotine self-administration in rats and mice. Psychopharmacology 167: 257–264.

Popik P, Wrobel M (2002). Morphine conditioned reward is inhibited by MPEP, the mGluR5 antagonist. Neuropharmacology 43: 1210–1217.

Popik P, Wrobel M, Rygula R, Bisaga A, Bespalov AY (2003). Effects of memantine, an NMDA receptor antagonist, on place preference conditioned with drug and nondrug reinforcers in mice. Behav Pharmacol 14: 237–244.

Schoepp DD (2001). Unveiling the functions of presynaptic metabotropic glutamate receptors in the central nervous system. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 299: 12–20.

Sharko AC, Hodge CW, Iller K, Koenig H, Lau K, Ou CJ et al (2002). Involvement of metabotropic glutamate receptor subtype 5 (mGlu5) in alcohol self-administration and sedation. Program No. 783.1 Abstract Viewer/Itinerary Planner. Washington, DC: Society for Neuroscience, 2002 (online).

Sheardown MJ, Nielsen EO, Hansen AJ, Jacobsen P, Honore T (1990). 2,3-Dihydroxy-6-nitro-7-sulfamoyl-benzo(F)quinoxaline: a neuroprotectant for cerebral ischemia. Science 247: 571–574.

Tessari M, Pilla M, Andreoli M, Hutcheson DM, Heidbreder CA (2004). Antagonism at metabotropic glutamate 5 receptors inhibits nicotine- and cocaine-taking behaviours and prevents nicotine-triggered relapse to nicotine-seeking. Eur J Pharmacol 499: 121–133.

Thomas LS, Jane DE, Gasparini F, Croucher MJ (2001). Glutamate release inhibiting properties of the novel mGlu(5) receptor antagonist 2-methyl-6-(phenylethynyl)-pyridine (MPEP): complementary in vitro and in vivo evidence. Neuropharmacology 41: 523–527.

Tzschentke TM, Schmidt WJ (1997). Interactions of MK-801 and GYKI 52466 with morphine and amphetamine in place preference conditioning and behavioural sensitization. Behav Brain Res 84: 99–107.

Weiss F, Maldonado-Vlaar CS, Parsons LH, Kerr TM, Smith DL, Ben-Shahar O (2000). Control of cocaine-seeking behavior by drug-associated stimuli in rats: effects on recovery of extinguished operant-responding and extracellular dopamine levels in amygdala and nucleus accumbens. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 97: 4321–4326.

Weiss F, Martin-Fardon R, Ciccocioppo R, Kerr TM, Smith DL, Ben-Shahar O (2001). Enduring resistance to extinction of cocaine-seeking behavior induced by drug-related cues. Neuropsychopharmacology 25: 361–372.

Acknowledgements

Supported by a grant from the Finnish Foundation for Alcohol Studies to P Bäckström.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Bäckström, P., Hyytiä, P. Ionotropic and Metabotropic Glutamate Receptor Antagonism Attenuates Cue-Induced Cocaine Seeking. Neuropsychopharmacol 31, 778–786 (2006). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.npp.1300845

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.npp.1300845