« Prev Next »

How are Endangered Species Identified?

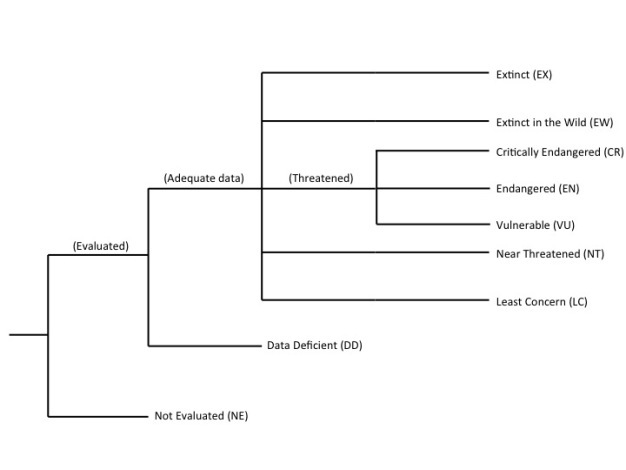

The International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources (IUCN) Red List uses a hierarchical structure of nine categories for assigning threat levels for each species or subspecies. These categories range from 'Extinct' to 'Least Concern' (Figure 1). At the highest levels of threat, taxa are listed as 'Critically Endangered,' 'Endangered,' or 'Vulnerable,' all of which are given 'Threatened' status. A series of quantitative criteria is measured for inclusion in these categories, including: reduction in population size, geographic range size and occupancy of area, total population size, and probability of extinction. The evaluation of these criteria includes analyses regarding the number of mature individuals, generation time, and population fragmentation. Each taxon is appraised using all criteria. However, since not all criteria are appropriate for assessing all taxa, satisfying any one criterion qualifies listing at that designated threat level.

There are a variety of human activities that contribute to species becoming threatened, including habitat destruction, fragmentation, and degradation, pollution, introduction of non-native species, disease, climate change, and over-exploitation. In many cases, multiple causes act in concert to threaten populations. Though the causes underlying population declines are numerous, some traits serve as predictors of whether species are likely to be more vulnerable to the causes listed. For example, many species that have become endangered exhibit large body size, specialized diet and/or habitat requirements, small population size, low reproductive output, limited geographic distribution, and great economic value (McKinney 1997).

How to Save Endangered Species

There are a variety of methods currently being implemented to save endangered species. The most common are creation of protected areas, captive breeding and reintroduction, conservation legislation, and increased public awareness.

Protected areas

An effective and internationally recognized strategy for conserving species and ecosystems is to designate protected areas. The United Nations Environment Programme World Conservation Monitoring Center (UNEP-WCMC) defines a protected area as "an area of land and/or sea especially dedicated to the protection of biological diversity and of natural and associated cultural resources, managed through legal or other effective means." Worldwide, extensive systems of protected areas have been developed and include national parks, state/provincial parks, wildlife refuges, and nature reserves, all of which differ in their management objectives and degree of protection. The IUCN has defined six protected area management categories, based on primary management objective (Table 1). These categories are defined in detail in the Guidelines for Protected Areas Management Categories published by IUCN in 1994.

|

Category Ia

Strict Nature Reserve: protected area managed mainly for science Definition: Area of land and/or sea possessing some outstanding or representative ecosystems, geological or physiological features and/or species, available primarily for scientific research and/or environmental monitoring. |

|

Category Ib

Wilderness Area: protected area managed mainly for wilderness protection Definition: Large area of unmodified or slightly modified land, and/or sea, retaining its natural character and influence, without permanent or significant habitation, which is protected and managed so as to preserve its natural condition. |

|

Category II

National Park: protected area managed mainly for ecosystem protection and recreation Definition: Natural area of land and/or sea, designated to (a) protect the ecological integrity of one or more ecosystems for present and future generations, (b) exclude exploitation or occupation inimical to the purposes of designation of the area and (c) provide a foundation for spiritual, scientific, educational, recreational and visitor opportunities, all of which must be environmentally and culturally compatible. |

|

Category III

Natural Monument: protected area managed mainly for conservation of specific natural features Definition: Area containing one or more specific natural or natural/cultural feature which is of outstanding or unique value because of its inherent rarity, representative or aesthetic qualities or cultural significance. |

|

Category IV

Habitat/Species Management Area: protected area managed mainly for conservation through management intervention Definition: Area of land and/or sea subject to active intervention for management purposes so as to ensure the maintenance of habitats and/or to meet the requirements of specific species. |

|

Category V

Protected Landscape/Seascape: protected area managed mainly for landscape/seascape conservation and recreation Definition: Area of land, with coast and sea as appropriate, where the interaction of people and nature over time has produced an area of distinct character with significant aesthetic, ecological and/or cultural value, and often with high biological diversity. Safeguarding the integrity of this traditional interaction is vital to the protection, maintenance and evolution of such an area. |

|

Category VI

Managed Resource Protected Area: protected area managed mainly for the sustainable use of natural ecosystems Definition: Area containing predominantly unmodified natural systems, managed to ensure long term protection and maintenance of biological diversity, while providing at the same time a sustainable flow of natural products and services to meet community needs. |

|

Table 1. Primary management objectives for the six protected area management categories as defined by the IUCN.

|

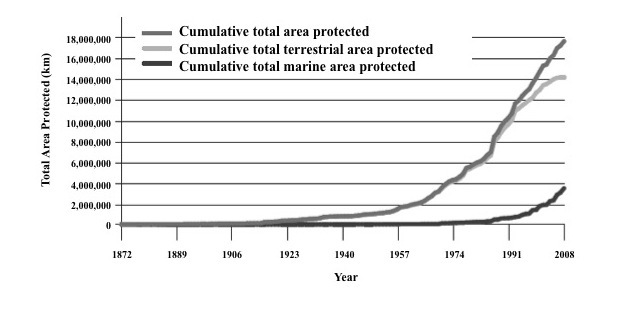

The World Database on Protected Areas (WDPA) records all nationally designated terrestrial and marine protected areas whose extent is known. These data are collected from national and regional governing bodies and non-governmental organizations. Currently, there are over 120,000 protected areas (2008 estimate, UNEP-WCMC), covering about 21 million square kilometers of land and sea. Since 1872, there has been a dramatic increase in the global number and extent of nationally designated protected areas (Figure 2). Well-planned and -managed protected areas not only benefit species at risk, but other species associated with them, thereby increasing the overall amount of biodiversity conserved. Despite increases in the size and number of protected areas, however, the overall area constitutes a small percentage of the earth's surface. Because these areas are critical to the conservation of biodiversity, the designation of more areas for protection and increases in the sizes of those areas already in existence are necessary.

2008 represented by cumulative total area, total terrestrial area, and

total marine area protected. Figure excludes protected areas with

unknown year of establishment. http://www.twentyten.net/pacoverage;

UNEP-WCMC 2009

Another opportunity for creating protected areas is the Alliance for Zero Extinction (AZE), an international consortium of conservation organizations that specifically targets protection of key sites that represent sanctuaries of one or more Endangered or Critically Endangered species. The AZE focuses on species whose habitats have been degraded or whose ranges are exceptionally small, making them susceptible to outside threats. Three criteria must be met in order to prioritize a site for protection (Table 2). To date, 588 sites encompassing 920 threatened species of mammals, birds, reptiles, amphibians, conifers and corals have been identified. The goal of such efforts is to prevent the most imminent species extinctions by increasing global awareness of these key areas.

| Category | Criteria |

| Endangerment | An AZE site must contain at least one Endangered or Critically Endangered species, as listed on the IUCN Red List. |

| Irreplaceability | An AZE site should only be designated if it is the sole area where and Endangered or Critically Endangered species occurs, contains the overwhelmingly significant known resident population (>95%) of the Endangered or Critically Endangered species, or contains the overwhelmingly significant known population (>95%) for one life history segment (e.g. breeding or wintering) of the Endangered or Critically Endangered species. |

| Discreteness | The area must have a definable boundary within the character of habitats, biological communities, and/or management issues have more in common with each other than they do with those in adjacent areas. |

| Table 2. Criteria for identifying sites for protection of Endangered or Critically Endangered species as defined by the AZE. | |

Captive breeding and reintroduction

Some species in danger of extinction in the wild are brought into captivity to either safeguard against imminent extinction or to increase population numbers. The primary goals of captive breeding programs are to establish populations via controlled breeding that are: a) large enough to be demographically stable; and b) genetically healthy (Ebenhard 1995). These objectives ensure that populations will exhibit a healthy age structure, resistance to disease, consistent reproduction, and preservation of the gene pool to minimize and/or avoid problems associated with inbreeding. Successful captive breeding programs include those for the Guam rail, scimitar-horned oryx, and Przewalski's horse. (See iucnredlist.org for details.)

Establishing captive populations is an important contribution of zoos and aquariums to the conservation of endangered species. Zoos and aquariums have limited space, however, so to maintain healthy populations, they cooperate in managing their collections as breeding populations from international to regional levels. The World Association of Zoos and Aquariums (WAZA) is the organization that unites the world's zoos and aquariums in cooperative breeding programs. Perhaps the most important tools in managing these programs are studbooks, which ensure that captive populations maintain a sufficient size, demographic stability, and ample genetic diversity. All information pertinent to management of the species in question is included (e.g., animal registration number, birth date, parentage, behavioral traits that may affect breeding). These studbooks are used to make recommendations regarding which individuals should be bred, how often, and with whom in order to minimize inbreeding and, thus, enhance the demographic and genetic security of the captive population.

Another goal of some captive breeding programs is to reintroduce animals to the wild to reestablish populations. Examples of successful introductions using captive-bred stock include California condors (Ralls & Ballou 2004) and black-footed ferrets (Russell et al. 1994). Reintroductions can also utilize individuals from healthy wild populations, meaning individuals that are thriving in one part of the range are introduced to an area where the species was extirpated. Reintroduction programs involve the release of individuals back into portions of their historic range, where they are monitored and either roam freely (e.g., gray wolves released in Yellowstone National Park) or are contained within an enclosed area (e.g., elk in Land Between the Lakes National Recreation Area in western Kentucky; Figure 3). However, reintroduction is only feasible if survival can be assured. Biologists must ascertain whether: a) the original threats persist and/or can be mitigated; and b) sufficient habitat remains, or else survival will be low upon release.

Laws and regulations

Biodiversity is protected by laws at state/provincial, national, and international levels. Arguably the most influential law is the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES) which is an agreement between governments (i.e., countries) that controls international trade in wild animals, plants, and their parts to ensure continued survival. International trade in wildlife is a multi-billion dollar industry that affects millions of plants and animals. As a result, CITES lists species in three Appendices according to the level of protection they require to avoid over-exploitation; species listed in Appendix I require the most protection and, thus, trade limitations (Table 3). Currently, approximately 30,000 species are protected under CITES (Table 4).

| Appendix | Level of Protection | Trade |

| Appendix I | Species threatened with extinction | Permitted only in exceptional circumstances |

| Appendix II | Species might be threatened with extinction but not required | Trade is controlled to ensure survival |

| Appendix III | Species are protected in at least one country | Trade is controlled after a member country has indicated that assistance is needed in this capacity |

| Table 3. Species and level of trade permitted depending on listing in CITES Appendix. | ||

| Appendix I | Appendix II | Appendix III | |

| Mammals | 297 spp. + 23 sspp. | 492 spp. + 5 sspp. | 44 spp. + 10 sspp. |

| Birds | 156 spp + 11 sspp. | 1275 spp. + 2 sspp. | 24 spp. |

| Reptiles | 76 spp. + 5 sspp. | 582 spp. | 56 spp. |

| Amphibians | 17 spp. | 113 spp. | 1 sp. |

| Fish | 15 spp. | 81 spp. | - |

| Invertebrates | 64 spp. + 5 sspp. | 2142 spp. + 1 sspp. | 22 spp. + 3 sspp. |

| Plants | 301 spp. + 4 sspp. | 29105 spp. | 119 spp. + 1 sspp. |

| Total | 926 spp. + 48 sspp. | 33790 spp. + 8 sspp. | 266 spp. + 14 sspp. |

| Table 4. Approximate number of species (spp.) and subspecies (sspp.) included in the CITES appendices since December 2011. | |||

The trade in wildlife is an international issue and, as such, cooperation between countries is required to regulate trade under CITES. However, member countries adhere to regulations voluntarily and, consequently, they must implement them. Most important, CITES does not take the place of national laws; member countries must also have their own domestic legislation in place to execute the Convention.

Public awareness

In general, the public is unaware about the current extinction crisis. Public awareness can be increased through education and citizen science programs. Conservation education often begins in elementary school and may be enhanced through summer camps or family vacations that are nature oriented (e.g., involve visiting national or state parks). Early positive experiences with nature are essential for children to gain an appreciation for wildlife and the problems species face. In high school, this education is continued through formal science education and extra-curricular activities. Other means of increasing public awareness involve internet websites where subscribers can receive emails from conservation organizations like Defenders of Wildlife, Environmental Defense, and World Wildlife Fund. In many cases, these organizations provide updates on the status of endangered species and promote letter writing to elected officials in requesting protection for endangered species and their habitats.

Citizen science refers to the actions of non-specialist volunteers who collect data to contribute to ongoing research. An example is the multinational Christmas Bird Count organized by the National Audubon Society. Through this program, volunteers have observed birds in their local communities for over a century, providing abundance data on wintering bird populations. Citizen science has also evolved to include the use of mobile technology. For instance, WildLab is an iPhone application used to quantify biodiversity (in this case, birds and marine life), with information sent via phone to Cornell University.

CASE STUDY IN CONSERVATION: Global declines in amphibian populations

Amphibians are one of the earth's most imperiled vertebrate groups, with approximately one-third of all species facing extinction (Stuart et al. 2004). Causes of amphibian population declines and extinctions echo those listed in the introductory paragraphs but primarily consist of drainage and development of wetland habitats and surrounding uplands, contamination of aquatic habitats, predation by or hybridization with introduced species, climate change, and over-harvesting (Collins & Storfer 2003). In addition, the recent declines observed in relatively pristine areas, such as state, provincial, and national parks worldwide have brought to light the tremendous impact of pathogens on amphibian populations, most notably that of the amphibian-killing fungus Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis (Bd). So what is being done to preserve amphibian diversity?

To address the historic sources of amphibian population declines, such as overexploitation and habitat loss, national and international legislation exists to monitor the trade in amphibians and prevent further reductions in available habitat. Although international trade in amphibians is less common relative to trade in other vertebrate groups, CITES currently lists 131 species in Appendices I-III. Furthermore, IUCN currently lists 509, 767, and 657 amphibian species as Critically Endangered, Endangered, or Vulnerable (Figure 4), respectively. These species' native habitats are afforded protection at various levels of organization. The AZE has identified 588 sites worldwide exhibiting at least one criterion for protection (Table 2), and these sites are home to hundreds of amphibian species listed by IUCN as between Vulnerable and Critically Endangered. In addition, IUCN's Amphibian Specialist Group (ASG) has partnered with governmental and non-governmental organizations and individuals to create new protected areas and minimize further population declines due to habitat fragmentation and loss. In addition to designation of new protected areas, efforts of the ASG include habitat restoration, promotion of ecotourism, and extended amphibian-monitoring programs.

Despite efforts to preserve suitable habitat, biologists became increasingly aware of catastrophic population declines associated with Bd, and more urgent action became necessary when declines were detected in protected areas with minimal risks of habitat loss and overexploitation. Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis is a parasitic fungus that disrupts the bodily processes of its amphibian hosts, resulting in lethargy and ultimately death. Although the exact origins of this pathogen are currently debated, Bd has been detected throughout the world and linked to dramatic amphibian population declines and extinctions (Skerratt et al. 2007).

Due to the rapidity with which Bd invades amphibian communities, swift conservation action was deemed necessary to prevent extinctions; consequently, many institutions realized the necessity of collecting wild individuals prior to the arrival of Bd with the hopes of establishing captive populations. The Amphibian Ark, for example, represents a joint effort between the ASG, the World Association of Zoos and Aquariums, and the IUCN/SSC Conservation Breeding Specialist Group. Members of these organizations worldwide participate in captive amphibian husbandry and breeding programs using wild-caught individuals (Figure 5-6). In concert with such activities, some facilities are also addressing the possibility of 'biobanking' activities, such as cryogenically preserving the sperm and eggs of imperiled species or maintaining living cell lines for future use. While some researchers are dedicated to maintaining captive populations, others are actively investigating potential treatments for Bd or preventative measures. Treatment methods are currently being investigated for amphibians already infected with Bd (Berger et al. 2010), and findings that certain bacteria confer Bd resistance have led some researchers to examine the viability of 'seeding' amphibians with protective bacterial coatings prior to reintroduction efforts (Becker and Harris 2010). Also, biologists are increasingly advocating for more rigorous chytrid monitoring protocols to prevent further spread of this pathogen, such as efforts in the United States to incorporate amphibians into the Lacey Act (1900), a federal mandate that would require them to be certified as disease-free prior to importation.

Throughout the current amphibian extinction crisis, increasing public awareness has been a critical component of conservation efforts. Amphibians typically do not receive the attention bestowed upon more charismatic megafauna, such as pandas and tigers, despite their significant economic, ecological, and aesthetic values. In a worldwide effort to bring amphibian population declines to the forefront, the Amphibian Ark declared 2008 as the "Year of the Frog," a time in which conservationists showcased amphibian diversity in zoos and aquaria while detailing their current plight. In addition, some conservation efforts, such as Project Golden Frog, utilize attractive or otherwise conspicuous amphibians as flagship species with which to garner public interest and local pride in endangered species and promote local activism (Figure 7). The ASG's 'Metamorphosis' initiative utilizes artistry to promote increase public recognition of connections between the plight of amphibians and that of humanity. Biologists have also solicited direct public involvement through citizen science programs wherein non-scientists can participate in crucial amphibian population monitoring efforts; examples of these efforts include ASG's Global Amphibian BioBlitz, Nature Canada, and Environment Canada's FrogWatch, the United States Geological Survey's North American Amphibian Monitoring Program, and the AZA's FrogWatch USA. Finally, continued research highlighting the critical ecological and economic roles amphibians play in ecosystems, such as transferring energy through food webs and reducing insect populations (Davic & Welsh 2004), has been important in cultivating popular interest in the current extinction crisis.

References and Recommended Reading

Berger, L., Speare R. et al. Treatment of chtridiomycosis requires urgent clinical trials. Diseases of Aquatic Organisms 92, 165-174 (2010).

Collins, J. P. & Storfer, A. Global amphibian declines: sorting the hypotheses. Diversity and Distributions 9, 89-98 (2003).

Davic, R. D. & Welsh, H. H. On the ecological roles of salamanders. Annual Review of Ecology, Evolution, and Systematics 35, 404-434 (2004).

Ebenhard, T. Conservation breeding as a tool for saving animal species from extinction. Trends in Ecology and Evolution 10, 438-443 (1995).

McKinney, M. L. Extinction vulnerability and selectivity: combining ecological and paleontological views. Annual Review of Ecology and Evolution 28, 495-516 (1997).

Ralls, K. & Ballou, J. D. Genetic status and management of California condors. Condor 106, 215-228 (2004).

Russell, W. C., Thorne, E. T. et al. The genetic basis of black-footed ferret reintroduction. Conservation Biology 8, 163-266 (1994).

Skerratt, L. F., Berger, L. et al. Spread of chytridiomycosis has caused the rapid global decline and extinction of frogs. Ecohealth 4, 125-134 (2007).

Stuart, S. N., Chanson, J. S. et al. Status and trends of amphibian declines and extinctions worldwide. Science 306, 1783-1786 (2004).