« Prev Next »

For the past thirteen years, I've lived and worked in Central Africa, studying primates and other large mammals such as forest elephants. My family and friends often ask questions about my work, such as "How do you avoid all the snakes?" "What do you do when you are attacked by leopards?" and "What about malaria?" It seems that the work of a field primatologist is widely perceived to be difficult, often dangerous, and, more than anything else, very exciting. I'm going to explain a little about what I, and others, actually do in the field, and hopefully give you an insight as to why impressions of excitement and danger might be both true and false.

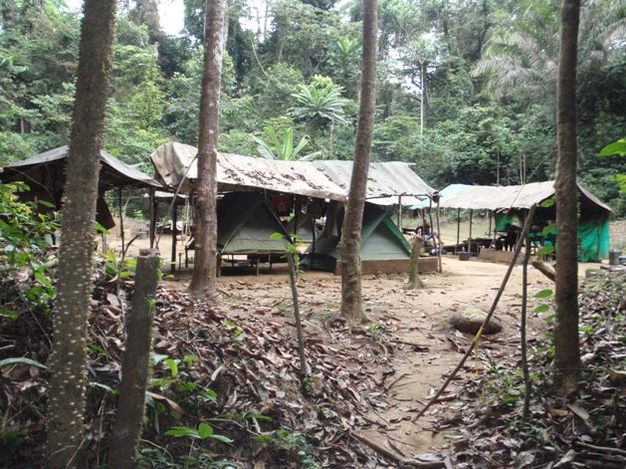

Our simian cousins live in a wide variety of wet, dry, lowland, mountainous, hot and cold environments across all continents straddling the equator. Most field primatological research is conducted from what I will call a research station. This could be a building, or series of buildings, with a laboratory and library, such as the Smithsonian's Barro Colorado Research Station in Panama, which hosts around 900 scientists annually. Some primatological pioneers have left a legacy of research stations that have evolved from what were originally basic camps to comfortable surroundings in which to live, such as at the Gombe Stream Research Centre, in Tanzania, and the Station D'Etudes des Gorilles et Chimpanzés in the Lope National Park, Gabon. Such sites usually have buildings constructed of local materials and access to running water and electricity (often generated through solar and/or hydroelectric power). Other research stations are more basically outfitted. At the Cocha Cashu Biological Station in Peru, after more than 25 years of continuous research work, the research station remains basic, with researchers sleeping in tents, and no running water or electricity. Other researchers base their operations from local communities — sometimes sharing someone's home. This has the obvious advantage of becoming part of the community over time, essential if understanding the relationship between the study primates and local human populations is one of the research goals. The research station in the proposed Ebo National Park, Cameroon, where I work is around eight hours' trek from the nearest village (Figure 1). There are no buildings, and any after-dark activities require oil lamps. Overall, the prospective primatologist shouldn't expect luxury-the goal of most research stations is to limit the amount of time needed to fulfill the most basic of human needs so that time for data collection can be maximised.

Let me try and give you a flavour of life at our ‘research station' in Cameroon. Since Ebo has not yet been officially designated as a National Park by the Government of Cameroon, we keep things basic, and sleep in tents covered by thick waterproof tarpaulins (Figure 2). The cooking area is modeled on a local village kitchen, with one main open fire used to cook the food and boil the drinking water. The latrine is a deep pit downstream from where we collect drinking water (Figure 3). We usually wash in the river, or take bucket baths, and clothes are also washed in the river. Drying clothes is very difficult during the rainy season, when the persistently high humidity means that mould flourishes, and the distinct fungal aroma is impossible to eliminate from our clothes.

We rise at around 05:30h, before dawn, and eat breakfast as the sun is about to rise. Our breakfast usually consists of ‘puffpuff' — deep fried dough balls — with mayonnaise or chocolate spread, and hyper-sweet coffee or tea. The breakfast menu is certainly an acquired taste, and underlines what I'll stress later-the ability to adapt to different conditions, or at least accept differences with a sense of humour! After breakfast, climate data are recorded for the previous 24-hour period, before teams of two people enter the forest for the day's work, carrying, at the very least, a compass, secateurs (the forest can be very thick in parts, but we strive to minimise disturbance to vegetation), notebooks/sheets and pencils, sample collection bags (for faeces, shed hairs, fruits or seeds), a camera, and lunch.

Whether the research stations are relatively luxurious or basic, life in the field itself is intense. Time spent away from the research station collecting data (for all daylight hours at most sites) is often arduous; in many regions, primates remain only in areas inaccessible to hunters and/or logging interests, which may mean high mountains and deep valleys to traverse. The types of data to be collected obviously depend on the research questions being addressed. I constantly bear in mind that data collection is the main reason for me being in the field, and whether those data are hand-written notes, photographs, videos, or biological samples for genetic and botanical studies, they are all as costly as the time and effort and funds it has taken me to get there — so I treat them as more valuable than gold dust.

One of the biggest differences between field sites depends on whether the study animals are habituated. Habituated animals are neither afraid of, nor very interested in their human observers — a state reached after a considerable amount of time and effort. Chloe Cipolletta and colleagues spent well over five years habituating a group of gorillas at Bai Hokou, Central Africa Republic — which was only possible due to a long-term commitment to the region by the Wordwide Fund for Nature (WWF). The ape habituation process relies on gradually increasing encounter rates with the species in question, as well as excellent tracking skills. In Ebo, several male individuals from two guenon species have self-habituated since 2005 — we believe this has happened because they are attracted to fruit trees around our research station, and their desire for the fruit has gradually triumphed over their fear of us.

Habituation renders animals vulnerable to poaching and other threats, since they lose their fear of humans, and hence ethical questions are paramount when deciding whether to habituate wild animals for research purposes. Habituated primates, however, offer unparalleled opportunities for behavioural research. Once habituated study animals are located, research might consist of detailing the behaviour of one individual animal (the focal animal) constantly throughout the day. These data might be supplemented by scanning the whole group and recording each individual's activity at a fixed time — perhaps every ten minutes. This kind of behavioural research will eventually necessitate statistical analyses, and it is extremely satisfying to know that the hours of recording what, at the time, appeared to be meaningless data, will eventually lead to answers to your original research questions.

On the other hand, studying non-habituated animals may lead to the frustration of not being able to glimpse your study species during the entire time in the field. Good planning should allow prediction of the likelihood of detecting the study species, and will likely lead to developing indirect methods of addressing research questions. Studying unhabituated animals can be frustrating, especially for rare reclusive animals such as the endangered drill. Drills are large, sexually dimorphic, semi-terrestrial primates that often move around the forest in large groups (Figure 4). Their elusive nature is legendary, and gathering even basic data on group sizes and sex/age composition is very difficult. Thus studies of unhabituated animals usually rely on indirect methods to address research questions (such as measuring the diameter of faeces in drills, as a proxy for the body size of the animal that deposited it) and often excellent tracking skills of both the species and the signs of its presence.

At Ebo, our research team also studies a population of gorillas using several indirect methods, such as recording detailed information on sleeping nests that does not require us to observe the gorillas directly. This information allows us to assess population size (since adults usually build fresh nests every night), social group sizes (individuals nest with their family members and/or friends), day range, and ultimately home range (by tracking groups from nest site to nest site). It is even possible to identify individual gorillas (through genetic analyses of shed hairs or faeces)-and all this in addition to documenting the characteristics of nests themselves.

Biologists may choose to study primates to answer theoretical research questions about, for example, aspects of behaviour or ecology. For example, the distribution and characteristics of nut-cracking behaviour of certain chimpanzee populations has been used as a ‘model' for understanding the development of tool use behaviour in human evolution. The Ebo chimpanzees share this behaviour with chimpanzees in the Tai forest, Ivory Coast, and westwards, whereas intermediate chimpanzee populations either have never ‘invented' this behaviour, or have ‘forgotten' it at some point in the past. Field primatologists also study primates to primarily improve their conservation status, perhaps by conducting regular monitoring surveys to inform management strategies, or engaging more closely with local communities to sensitise them on the threats to endangered species. An important part of our work is conserving the many elusive species in the proposed Ebo National Park, and we can use our monitoring records to track changes in population size and the overall ‘health' of primate populations. The majority of field sites, however, engage collaborators to accomplish both research and conservation goals, since they are, ultimately, both complementary and mutually dependent.

On returning to the research station with our hard-earned data, whether they are written on old-fashioned paper and pen, or in some electronic format (for example, using a voice recorder for behavioural data, or ‘Cybertracker' (software on a hand-held computer with built-in GPS logger), logging and archiving results is a priority — anecdotes about losing data abound. It is also advisable to regularly review data, to make sure that the research questions will be able to be answered with the data that are being collected. And, sooner or later, the data will leave the field and arrive at an office, where data analysis can begin in earnest. Ultimately, these data will provide the world with the answers to the original research questions. It is all too easy for field primatologists to get waylaid by the day-to-day logistical issues of life in the tropics. ‘Publish or perish' is not only a threat to the field primatologist, but also to our study animals. If we do not give the outside world the information needed to show how fascinatingly fast/slow/peaceful/violent/kind/selfish our study animals are, we can hardly expect the general public to empathise with our desire to preserve the habitat for that species over the desire for a new timber concession, or to attract funding for further primatological studies. This includes ensuring that results are lodged with the relevant national wildlife authorities — this is usually a legal requirement, and is absolutely vital to ensure that we do not jeopardise the research possibilities of future field primatologists.

At the end of a hard field day, we usually take it in turns to cook (Figure 5). The staple food at our research station is some form of dried tuber, such as cassava, or yams, rice, or plantains. This is served with a sauce based on peanuts (ground nuts), pumpkin seeds, okra, or more rarely tinned tomato paste, with onions, perhaps cabbage, and usually dried fish. All these foods last for several weeks with the correct care, and are relatively easy to transport. After our impossibly-sized meals, we play cards or continue our ongoing ludo championship by lamp-light, and are snoring contentedly well before 21:00h.

In addition to the day-to-day activities I've outlined, I've found two other aspects of life in the field that need particular attention if you are to succeed as a field primatologist. First, physical health and personal safety need to be taken seriously, otherwise not only you but also the entire research team and wider community can suffer. I have witnessed the speed and devastation that malaria and other tropical diseases can wreak. Knowing what do before you are affected, and making sure others around you are equally aware, must be a priority. Basic sanitation is vital in tropical areas of the world, as is minimising risk while travelling, since road safety is woefully inadequate in most developing countries. Do not take unnecessary risks (we do not travel at night, for example) and do not be afraid to constantly reassess behaviour and risks, and err on the safe side where there is a conflict. Additionally, be aware that our close evolutionary relationship with non-human primates raises serious concerns in terms of spreading contagious diseases. Detailed IUCN Primate Specialist Group guidelines for disease monitoring of apes are currently being written, but staying away from the forest when unwell, wearing a surgical mask when in close contact with primates, and burying urine and faeces when away from the research station are sensible precautions that should at taken in the majority of field sites, and constitutes part of our duty as field primatologists.

Second, I've found it essential to regularly reflect on my behaviour and interaction with others. Living in a foreign culture inevitably results in ignorance of some intricacies of the cultural norms. Even within one country, the difference between acceptable behaviours in cities and villages or between cultures can be enormous. It is very important to realise that data collection is only possible through collaboration with field assistants, cooks, porters, drivers, village chiefs, and so on. Experienced field primatologists realise that their work would be impossible without good working relationships, and treat their colleagues and the culture in which they are working with deserved respect.

So how do I respond to the questions I'm so often asked? Snakes: I see them perhaps once a week, and have never known a colleague to be bitten. Leopards: I'd give my right arm to see one — they have already become extinct in many Central African forests. Malaria: well worth being scared of. This terrible disease hits hard and fast, and all field workers in malaria-affected areas should have emergency protocols, shared with others, for starting treatment within hours of symptoms appearing — often characterised by rapid changes in body temperature, headaches, and body aches. In remote locations, this may mean carrying a thermometer and anti-malarials permanently.

But overall, the joy I get from simply being in the forest in which (mostly unhabituated) study primates live, more than compensates for the down sides to my work (Figure 6). I now try and see these questions as an opportunity to share some of the wonders of studying and conserving our primate cousins.