Abstract

Intrinsic ripples in freestanding graphene have been exceedingly difficult to study. Individual ripple geometry was recently imaged using scanning tunnelling microscopy, but these measurements are limited to static configurations. Thermally-activated flexural phonon modes should generate dynamic changes in curvature. Here we show how to track the vertical movement of a one-square-angstrom region of freestanding graphene using scanning tunnelling microscopy, thereby allowing measurement of the out-of-plane time trajectory and fluctuations over long time periods. We also present a model from elasticity theory to explain the very-low-frequency oscillations. Unexpectedly, we sometimes detect a sudden colossal jump, which we interpret as due to mirror buckling. This innovative technique provides a much needed atomic-scale probe for the time-dependent behaviours of intrinsic ripples. The discovery of this novel progenitor represents a fundamental advance in the use of scanning tunnelling microscopy, which together with the application of a thermal load provides a low-frequency nano-resonator.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Tracking the movement of individual atoms has its origins in field ion microscopy1. The invention of scanning tunnelling microscopy (STM), however, marked the birth of a new era, famously allowing Mo et al.2, for instance, to observe the migration of Si atoms on the Si(001) surface and extract the activation energy for diffusion. Swartzentruber went a step further by programming the STM tip to physically follow each step of a single diffusing atom, thereby recording its site-to-site movement3. In this tradition, but for freestanding graphene, it would be ideal to monitor the out-of-plane motions of the carbon atoms. These fluctuations4 are linked to the flexural phonon modes, which are critical to many of graphene’s amazing properties, such as its previously unpredicted stability5,6, anomalous negative coefficient of thermal expansion7 and efficient thermal conductivity8,9. The ripples that form10,11 are also important for understanding transport properties in graphene, as they decrease the carrier mobility in freestanding membranes12, cause disruptive charge puddling13 and induce strong pseudo-magnetic fields14. The ability to locally measure the thermal fluctuations as a function of time will open the door to directly testing their role in these and other important processes.

Here, we report the utilization of STM to precisely monitor the out-of-plane motions of a one-square-angstrom region in freestanding graphene for the first time. The observed fluctuations are found to exhibit random, periodic or mirror-buckling behaviour. The periodic oscillations have current-dependent characteristics, which are shown to be consistent with the predictions of elasticity theory under the influence of thermal stress. No other technique has demonstrated the ability to probe such low-frequency flexural phonon modes at the atomic scale, permitting direct investigation of the dynamic ripples that affect almost every property of graphene. We expect that the new technique will lead to new experiments in graphene, ranging from fundamental to thermal load applications.

Results

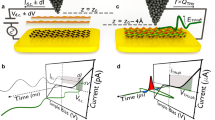

STM tip interaction with freestanding graphene

Increasingly, STM is becoming the tool of choice to manipulate and map suspended graphene15,16,17,18. As the STM tip approaches a roughened, freestanding graphene layer, depicted in Fig. 1a, it may have two significant effects on the sample. (For full system and sample descriptions, see Methods and Supplementary Fig. 1) The first depends on the potential difference V between the positively biased tip and the grounded sample, as demonstrated in the inset of Fig. 1b. When the voltage is increased from 0.1 to 3.0 V at a constant tunnelling current of 1.00 nA, the tip height increases 20 nm. From the size of this displacement and the requirement of constant current, we can conclude that the flexible graphene has also moved about 20 nm locally due to electrostatic attraction19. Since the electrostatic force depends quadratically20 on the bias voltage (∝V2), we re-plot V2 as a function of tip height in the main graph of Fig. 1b. The main plot is divided into four regions for discussion purposes: (I) low-bias voltages where V2<0.1 V2, (II) voltages between 0.1 V2 and 1 V2, (III) voltages between 1 V2 and 4 V2 and (IV) voltages beyond 4 V2. In region (I) where the film has not been pulled very high, we believe the thermal contribution to the energy is much larger than the electrostatic one. After that, in region (II) where most of the height change happens, the electrostatic force (Fe∝V2) is proportional to the height variation (ΔZ), and the system obeys Hooke’s law (linear region). Next, in region (III) the electrostatic force is no longer proportional to the height variation, and the nonlinear effects become important. Finally, in region (IV) there is no further increase in the height with increasing voltage, meaning the graphene sheet is fully pulled up (that is, tense membrane boundary condition) and becomes inflexible.

(a) Depiction of a biased scanning tunnelling microscopy (STM) tip as it is brought near a suspended, grounded graphene sample with intrinsic roughening. As in our STM system, the tip approaches from below, but the measured tip height increases as it moves away from the sample. (b) The change in STM tip height at one location on freestanding graphene as a function of bias voltage. It increases by 20 nm as the voltage is ramped from 0.1 to 3.0 V at 1.00 nA, as shown in the inset (see Supplementary Fig. 3). The main plot is rescaled to show V2 as a function of height because V2 is proportional to the electrostatic force. The four regimes present in the data are: (I) thermal fluctuations, (II) linear elasticity, (III) nonlinear elasticity and (IV) boundary effects. (c) The change in STM tip height at one location on freestanding graphene as a function of tunnelling current. The experimental height decreases by 20 nm as the current is raised from 0.01 to 1.00 nA at 0.1 V, and this behaviour can be replicated by equation (1). The error bars in Fig. 1b,c represent the s.d. of 10 repeated measurements taken consecutively at the same location of the sample.

The second important effect caused by the STM tip is heating of the sample by passing current through it, as evidenced in Fig. 1c. Here the tunnelling current is ramped from 0.01 to 1.00 nA at a constant tip bias of 0.1 V, and the displacement is −20 nm. Note this behaviour cannot be due to an electrostatic effect. The tunnelling gap will be slightly reduced to accommodate the slightly larger setpoint current, but this would increase the electrostatic force, resulting in a height increase rather than a decrease. However, increasing the current does locally heat the graphene21. Thus, this behaviour can be attributed to the negative thermal expansion coefficient of graphene, which causes it to contract as the temperature of the graphene under the tip is increased. We assume that, in the steady state, the temperature rise under the tip is proportional to the power of the Joule heating at the junction (∝I2). Then the local height of the graphene under the tip decreases as  due to contraction, where h0=h(I=0) depends on V, while the constant k depends on graphene’s thermal conductivity and expansion coefficient, as well as on the tip-sample separation

due to contraction, where h0=h(I=0) depends on V, while the constant k depends on graphene’s thermal conductivity and expansion coefficient, as well as on the tip-sample separation  (see Supplementary Note 1). A typical value of the decay constant c is 1 Å−1, and the contact resistance R0 is typically 13 kΩ. However, at constant V we can let D=a In(I) and determine the unknown parameters by fitting the total tip height

(see Supplementary Note 1). A typical value of the decay constant c is 1 Å−1, and the contact resistance R0 is typically 13 kΩ. However, at constant V we can let D=a In(I) and determine the unknown parameters by fitting the total tip height

to the experimental data, as shown by the red curve in Fig. 1c, which is in good agreement with our experimental results. Note that the offset is necessary because the absolute starting height is unknown; it is set to zero for convenience. Although our fluctuation measurements take place at a constant voltage V0 and constant current I0, the two simple experiments above clearly indicate that the chosen tunnelling parameters may have a significant impact on our results.

Fluctuation behaviours of graphene and theoretical analysis

Three different qualitative categories of behaviour can be distinguished among the collected fluctuation information. We call the first and most common type, featured in Fig. 2, ‘random’ because no pattern or special feature is apparent. All data were recorded by taking a 0.1 nm × 0.1 nm STM image on freestanding graphene, such as the example shown in Fig. 2a (lower image). To understand the size of this scan relative to the lattice of atoms in graphene, refer to the 0.1 × 0.1 nm2 outlined in the upper STM image, which was acquired separately from a stabilized region of the same freestanding graphene sample. The lower image (400 × 400 data points) shows the height of the tip in a black-to-orange-to-white colour scale and is oriented such that the slow scan direction is horizontal and the fast scan is vertical. Note that significant changes in height rarely occur within a single vertical line. Therefore, a height-time signal was extracted along the slow scan direction by averaging the 400 points in each vertical line, resulting in a sampling frequency of 1 Hz over 400 s, as shown in Fig. 2b. The unique power of this technique is that it effectively monitors the vertical position of a one-atom sized region for a long period of time. Normal imaging covers too large an area to determine how any one location changes on a short timescale, and spectroscopy measurements like those in Fig. 1 happen too quickly to observe these fluctuations, though focused in one spot.

(a) A 1 nm × 1 nm filled-state scanning tunnelling microscopy (STM) image of freestanding graphene with a box highlighting the size of a one-square-angstrom region. A one-square-angstrom STM image taken at constant current (0.20 nA) and voltage (0.01 V) on freestanding graphene, showing the height fluctuations over a time of 400 s. The slow scan direction is oriented horizontally. Scale bar, 0.02 nm. (b) Height fluctuations as a function of time, taken by averaging the points in each vertical line of the lower STM image. For comparison, the same data were collected from a sample of gold. The error bar represents the s.d. of the 400 data points in the fast scan direction. (c) Actual tunnelling current measured concurrently with the height fluctuations. (d) Autocovariance of the height data, with an exponential decay constant of 8 s.

The result on freestanding graphene is that the height displacements greatly exceed the scale of the scan area. In this low bias regime (0.01 V), thermal energy is dominant22. The graphene height in Fig. 2b fluctuates around zero (average height was subtracted from the raw data) with a s.d. of 1.47 nm, an indication of the amplitude of wrinkles present in graphene (see Supplementary Fig. 2). For comparison, data taken in exactly the same manner on a sample of gold are also plotted, showing only the smallest changes in height over the entire scan. In addition, we always verify that graphene is indeed moving with the tip by measuring the tunnelling current as a function of time, displayed in Fig. 2c. It is almost constant at the setpoint value (0.2 nA), and the variations that do occur are not large enough to account for 3 nm fluctuations in the tip height without the sample also moving. We further characterize each height-time data set by calculating its autocovariance function A(t), which is plotted in Fig. 2d. A(t) decays exponentially for random fluctuations, indicating that they are only correlated for short periods of time. In this example, the decay constant is 8 s.

When we increase the tunnelling current, freestanding graphene exhibits noticeable periodic oscillations as represented in Fig. 3. Two samples of height-time data, taken at different currents but at the same location and the same low voltage (to avoid stretching), are displayed in Fig. 3a. The most noticeable difference is in the peak-to-peak amplitude; however, the fluctuations in both appear to have a roughly repeated character, which was confirmed by calculating A(t) for each curve, plotted in Fig. 3b. Its peaks share the periodicity of the signal, which is clearly around 100 s at 3 nA and 50 s at 5 nA. Conveniently, the linear susceptibility χ(t) can also be obtained from A(t) according to

(a) Four line profiles taken in the same manner as those in Fig. 2b. All were acquired at a tip bias of 0.01 V, but the tunnelling current was 3.00 nA for the top set and 5.00 nA for the bottom set. The error bars represent the s.d. of the 400 data points in the fast scan direction. (b) Associated A(t) for each graphene curve in part a. This function shares the periodicity of the signal. Smoothed first derivatives (related to the linear response) were calculated using the Savitzky-Golay algorithm and are plotted as insets. (c) Power spectral density for each graphene curve in part a, revealing the primary oscillation frequencies. (d) The primary frequency as a function of I2 for four images taken with a tip bias of 0.01 V. A trend line has been added to demonstrate the linear relationship of the data. (e) The height variance as a function of I−4 for four images taken with a tip bias of 0.01 V.

where kB is the Boltzmann constant and T is the absolute temperature23. dA/dt is therefore plotted as an inset for each curve in Fig. 3b and gives a maximum susceptibility of 5 nm2 s−1. Furthermore,  , the Fourier transform of χ(t), can in turn be related to the power spectral density S(ω) by the fluctuation-dissipation theorem, which states

, the Fourier transform of χ(t), can in turn be related to the power spectral density S(ω) by the fluctuation-dissipation theorem, which states

where ω is the frequency. The periodogram, an estimate of S(ω), was computed for the periodic results and plotted in Fig. 3c. The 3 nA spectrum has a prominent maximum near a frequency of 0.01 Hz, and gives a maximum power spectral density of 9,000 nm2 Hz−1. Meanwhile, the 5 nA spectrum peaks around 0.02 Hz and gives a smaller maximum power spectral density of 1,500 nm2 Hz−1. These low-frequency peaks represent the dissipation of thermal energy through flexural acoustic modes near the Brillouin zone centre24,25,26.

However, if we model the freestanding graphene sample as a doubly clamped resonator with length L=7.5 μm (see Methods) and mass density ρ subjected to an initial strain ε, plate theory predicts a resonance frequency given by  , where Y=340 Nm−1 is the Young’s modulus. This results in frequencies in the GHz range27, which is much too large. Therefore, to explain the experimental data using elasticity theory, we must invoke a different mechanism. Since the measurements in Fig. 3a are performed in the limit of high electric current (that is, temperature) and low bias voltage (but it is not negligible, see Supplementary Note 2), there are additional terms in the stress tensor28:

, where Y=340 Nm−1 is the Young’s modulus. This results in frequencies in the GHz range27, which is much too large. Therefore, to explain the experimental data using elasticity theory, we must invoke a different mechanism. Since the measurements in Fig. 3a are performed in the limit of high electric current (that is, temperature) and low bias voltage (but it is not negligible, see Supplementary Note 2), there are additional terms in the stress tensor28:

where the Lamé coefficient μ characterizes the shear rigidity of graphene,  is the bulk modulus29 and α≈5 × 10−6 K−1 is the absolute value of the thermal expansion coefficient at room temperature. The last term represents the thermal stress due to the temperature gradient near the tip region and the supports. In the steady state, ΔT is constant for a given electric current. In the presence of thermal stress, using equation (4) and the corresponding equation of motion for the graphene membrane results in the following flexural phonon frequency (see Supplementary Notes 3,4):

is the bulk modulus29 and α≈5 × 10−6 K−1 is the absolute value of the thermal expansion coefficient at room temperature. The last term represents the thermal stress due to the temperature gradient near the tip region and the supports. In the steady state, ΔT is constant for a given electric current. In the presence of thermal stress, using equation (4) and the corresponding equation of motion for the graphene membrane results in the following flexural phonon frequency (see Supplementary Notes 3,4):

where κ is the bending rigidity of graphene, ρ≅7.6 × 10−7 kg m−2 is the mass density and τ=−BαΔT is the effective negative surface tension. Since ΔT>0, equation (5) can result in low frequencies. The critical wave vector is determined as

Using typical values12 of κ=1.1 eV and B=208 Nm−1, we can estimate the critical wave vector, which attains realistic values for low ΔT. For example, at ΔT≃10 K, ΔT≃20 K and ΔT≃100 K the corresponding wavelengths are around 26, 18 and 8 nm, respectively. Note that longer critical wavelengths would be expected when other external stress sources exist; for example, when scanning close to the boundary or in the presence of a strong asymmetry.

By defining  , we can rewrite equation (5) as

, we can rewrite equation (5) as

and for q near to qc equation (7) results in small frequencies and  . Therefore, the larger the electric current, the larger the frequency when q is very close to qc. We confirm this prediction in Fig. 3d by plotting the primary oscillation frequency as a function of I2 and a linear trend line for four different scans obtained at the same low bias voltage. Furthermore, we can deduce based on the aforementioned theory that the bottom panel in Fig. 3a is more affected by thermal stress than the top panel. Also, the height variance should approximately obey ‹h2›∝I−4, which is in agreement with these four different electric currents as shown in Fig. 3e. In fact, these results are evidence for the softening of flexural phonons in the case of compressive strain in graphene. This result has been theoretically predicted using density functional theory calculations combined with non-linear classical elasticity theory7,30.

. Therefore, the larger the electric current, the larger the frequency when q is very close to qc. We confirm this prediction in Fig. 3d by plotting the primary oscillation frequency as a function of I2 and a linear trend line for four different scans obtained at the same low bias voltage. Furthermore, we can deduce based on the aforementioned theory that the bottom panel in Fig. 3a is more affected by thermal stress than the top panel. Also, the height variance should approximately obey ‹h2›∝I−4, which is in agreement with these four different electric currents as shown in Fig. 3e. In fact, these results are evidence for the softening of flexural phonons in the case of compressive strain in graphene. This result has been theoretically predicted using density functional theory calculations combined with non-linear classical elasticity theory7,30.

The last category of fluctuations discovered appears to exhibit a ‘mirror buckling’ effect and is explored in Fig. 4. The example STM image shown in Fig. 4a is very dark for the first fourth of the image and nearly white for the rest, signalling that a sudden jump has occurred, which is much larger than the variations before or after. A height-time profile, extracted in the manner previously described, is plotted in Fig. 4b to reveal that the membrane surprisingly undergoes an enormous 60 nm displacement around t=100 s but oscillates relatively little after the jump, somewhat similar to a critical transition. Examining the tunnelling current as a function of time as provided in Fig. 4c verifies that the sudden displacement is a real effect. Because the current is reasonably constant at 4 nA except for a spike coinciding with the jump in height, and since the spike is well below the system’s saturation current of 50 nA, tunnelling was never compromised. Height profiles such as this yield an unusual A(t), plotted in Fig. 4d. It takes a much longer time to decay, and its value at t=0 (equivalent to the variance ‹h2›) is anomalously large. The snap-through behaviour can typically be produced by performing a series of scans at progressively larger currents, keeping the voltage constant. The Fig. 4 data were part of such a series, and the variance from each successive scan is recorded in Fig. 4e. The large peak at 4 nA corresponds to the critical-like transition, which normally only occurs once as the current is increased within these limits, but not always at the same current.

(a) scanning tunnelling microscopy (STM) image of freestanding graphene, acquired in the same manner as that in Fig. 2a, but at a current of 4.00 nA and voltage of 0.1 V. Scale bar, 0.02 nm. (b) Height profile extracted from the STM image and showing a jump of nearly 60 nm at t=100 s, mimicking a critical transition. Corresponding data from a gold sample are provided for comparison. The error bars represent the s.d. of the 400 data points in the fast scan direction. (c) The measured tunnelling current, which shows a large but unsaturated spike coinciding with the large, sudden displacement. (d) A(t) for the graphene data. (e) The variance of the height-time graphs from images collected as the setpoint current was increased at a constant tip bias of 0.1 V. It is anomalously large when the mirror buckling effect occurs. (f) Series of illustrations depicting the stages of mirror buckling for a hemispherical shell. Corresponding labels are applied to the data in b. A sudden inversion in the curvature occurs at the critical pressure, just before Stage 3.

This unusual and unexpected event is a result of heating the sample in the presence of an attractive force. We can interpret this effect as due to mirror buckling of a thin shell. For example, for a spherical shell with radius R, the critical pressure that causes mirror buckling is estimated as31,32

where  , and both κ and Y will be modified by heating and the presence of an electrostatic force. By increasing temperature (electric current), Y is reduced, and a lower bias voltage is required to invert the buckled structure. Also, a larger radius lowers the voltage that leads to a flip. At this specific current and voltage, a large buckled region below the tip is heated for 100 s and then suddenly changes its curvature from negative to positive, that is, it switches from a bowl-like to a bump-like shape. This process is illustrated in Fig. 4f. During Stage 1 (also labelled in Fig. 4b), the height increases as the tip begins to deform the bowl. A metastable state is reached at Stage 2 where the force is not large enough to keep altering the local graphene configuration. However, the critical pressure is finally reached as the temperature continues to rise, leading the system to suddenly switch to the more stable bump shape shown in Stage 3.

, and both κ and Y will be modified by heating and the presence of an electrostatic force. By increasing temperature (electric current), Y is reduced, and a lower bias voltage is required to invert the buckled structure. Also, a larger radius lowers the voltage that leads to a flip. At this specific current and voltage, a large buckled region below the tip is heated for 100 s and then suddenly changes its curvature from negative to positive, that is, it switches from a bowl-like to a bump-like shape. This process is illustrated in Fig. 4f. During Stage 1 (also labelled in Fig. 4b), the height increases as the tip begins to deform the bowl. A metastable state is reached at Stage 2 where the force is not large enough to keep altering the local graphene configuration. However, the critical pressure is finally reached as the temperature continues to rise, leading the system to suddenly switch to the more stable bump shape shown in Stage 3.

The ripples of freestanding graphene were first imaged using STM in the pioneering work of Zan et al.15 They were able to establish the general topography of the ripples, which is the critical link to the general stability of 2D systems. What they found, using a STM set-up similar to ours, was that the height of the ripples is on the order of 1 nm and that the wavelength is on the order of 5 to 10 nm. The researchers also report that the ripple structure is static in time and is stable enough to repeatedly image the surface topography. At first, this seems to contradict our results. However, Zan et al.15 also report that the freestanding graphene sheet has regions that are too unstable to image with the STM (that is, when they look in a region far from the copper bar supports). This is also what we found. The surface of the graphene fluctuates too quickly for the STM to acquire constant-current images of the surface topography. However, we have been able to tunnel into the graphene sheet at that one spot, maintain a constant current and record the height changes occurring in time. Sometimes the surface will spontaneously stabilize as shown in Fig. 4b, and then, if it stays that way, it can be imaged with the STM.

Discussion

We have here demonstrated a way to gain unprecedented insight into the dynamics of ripples of freestanding graphene using the versatility of STM. While imaging an area corresponding to a single carbon atom, the vertical movement of the graphene is easily monitored with unparalleled precision. A degree of control over the shape and temperature of the membrane is applied through changing the tunnelling parameters. The observed fluctuations are generally large and can be sorted based on exhibiting random, periodic or mirror-buckling behaviour. In particular, the periodic oscillations and their current-dependent characteristics were shown to be consistent with the predictions of elasticity theory under the influence of thermal stress. No other technique has demonstrated the ability to probe such low-frequency flexural phonon modes at the atomic scale, permitting direct investigation of the dynamic ripples that affect almost every property of graphene. Furthermore, the biological timescale of the fluctuations (50 and 100 s) observed here advanced our fundamental understanding of membrane dynamics. We expect that the new technique will lead to new experiments in graphene, ranging from fundamental to advanced quantum charge control and thermal load application.

Methods

Scanning tunnelling microscopy

An Omicron ultrahigh-vacuum (base pressure is 10−10 mbar), low-temperature model STM, operated at room temperature, was used to obtain constant-current STM images of gold and freestanding graphene, as well as feedback-on measurements of tip height as a function of either bias voltage or setpoint current. In this system, the tip points upwards at the downward-facing sample surface. All images were collected at a scale of 0.1 nm × 0.1 nm, at a scan rate of 0.2 nm s−1 and had 400 data points per line with 400 lines per image. For each line, the topographical data were collected simultaneously with the tunnelling current in both the forward and backward scanning directions. In this way, each line took 1 s to complete for a total of 400 s per image. All STM images presented are 400 × 400 pixels and have a black-to-orange-to-white colour scale.

The electronics (cabling and preamplification in particular) used for these experiments effectively act as a low-pass filter with a bandwidth (−3 dB) of approximately 800 Hz. In addition, the speed at which we acquire digital data is 800 points per second, so we have a maximum frequency of 800 Hz that we can measure. Finally, for the height-time data presented in Figs 2, 3, 4 we collect digital data for 400 s, giving us a minimum detectable frequency of 0.0025 Hz. The error bars added to Fig. 1b,c represent the s.d. of 10 repeated measurements taken consecutively at the same location of the sample. The error bars added to Figs 2b, 3a and 4b represent the s.d. of the 400 data points in the fast scan direction of the acquired 400 by 400 data point STM image. The results presented here are typical examples. We have collected numerous data sets from each location we studied; we have studied numerous locations on each sample and we have studied many different samples.

The graphene was grown using chemical vapour deposition33, then transferred onto a 2000-mesh, ultrafine copper grid—a lattice of square holes 7.5 μm wide and bar supports 5 μm wide—by the commercial provider. At the STM facility, this grid was mounted on a flat tantalum sample plate using silver paint and transferred through a load-lock into the STM chamber, where it was electrically grounded for all experiments. Data were acquired using tips manufactured in-house by electrochemical etching of polycrystalline tungsten wire, using a custom double-lamella set-up with automatic gravity-switch cutoff. After etching, the tips were gently rinsed with distilled water, briefly dipped in a concentrated hydrofluoric acid solution to remove surface oxides and loaded into the STM chamber. A positive bias voltage was applied to the tip in all experiments.

These are difficult STM measurements, so we are adding some extra details here about our effort. First, the freestanding graphene is attached to only one side of the Cu grid. From our scanning electron microscope and energy dispersive X-ray analysis experiments (not reported here), we have confirmed that the freestanding graphene covers 90% of the surface and is free of detectable contamination. We have successfully done the experiments reported here with the freestanding graphene side of the sample facing up as well as facing down. When the sample is facing down, the Cu grid is supported on a stand-off support so the graphene cannot come into contact with the STM sample holder. The STM tip monitors the freestanding graphene through the holes of the Cu grid, and we have had fewer problems with stability in the downward-facing configuration. When the sample is loaded into the STM load-lock chamber, only lamp-type heating is applied, and no other heating or annealing is done to the sample. We are concerned that excessive annealing may cause macroscopic texturing due to the Cu grid expanding and the graphene contracting during the heating process11. About 10% of the time, after approaching the freestanding graphene surface, the STM cannot establish stable constant-current tunnelling and we move to a new location. Most of the time, we can establish stable constant-current tunnelling, but once we attempt to acquire an STM image of any appreciable size the constant-current tunnelling cannot be maintained. Consequently, we reduced the scan size to a single spot and then recorded the movement of the surface in time while maintaining a constant tunnelling current.

Additional information

How to cite this article: Xu, P. et al. Unusual ultra-low frequency fluctuations in freestanding graphene. Nat. Commun. 5:3720 doi: 10.1038/ncomms4720 (2014).

References

Ehrlich, G. & Hudda, F. G. Atomic view of surface self-diffusion: tungsten on tungsten. J. Chem. Phys. 44, 1039–1049 (1966).

Mo, Y. W., Kleiner, J., Webb, M. B. & Lagally, M. G. Activation energy for surface diffusion of Si on Si(001): a scanning-tunneling-microscopy study. Phys. Rev. Lett. 66, 1998–2001 (1991).

Swartzentruber, B. S. Direct measurement of surface diffusion using atom-tracking scanning tunneling microscopy. Phys. Rev. Lett. 76, 459–462 (1996).

Smolyanitsky, A. & Tewary, V. K. Manipulation of graphene's dynamic ripples by local harmonic out-of-plane excitation. Nanotechnology 24, 055701 (2013).

Fasolino, A., Los, J. H. & Katsnelson, M. I. Intrinsic ripples in graphene. Nat. Mater. 6, 858–861 (2007).

Meyer, J. C. et al. On the roughness of single- and bi-layer graphene membranes. Solid State Commun. 143, 101–109 (2007).

de Andres, P. L., Guinea, F. & Katsnelson, M. I. Bending modes, anharmonic effects, and thermal expansion coefficient in single-layer and multilayer graphene. Phys. Rev. B 86, 144103 (2012).

Lindsay, L., Broido, D. A. & Mingo, N. Flexural phonons and thermal transport in graphene. Phys. Rev. B 82, 115427 (2010).

Balandin, A. A. et al. Superior thermal conductivity of single-layer graphene. Nano Lett. 8, 902–907 (2008).

Meyer, J. C. et al. The structure of suspended graphene sheets. Nature 446, 60–63 (2007).

Bao, W. et al. Controlled ripple texturing of suspended graphene and ultrathin graphite membranes. Nat. Nanotech. 4, 562–566 (2009).

Castro, E. V. et al. Limits on charge carrier mobility in suspended graphene due to flexural phonons. Phys. Rev. Lett. 105, 266601 (2010).

Partovi-Azar, P., Nafari, N. & Tabar, M. R. R. Interplay between geometrical structure and electronic properties in rippled free-standing graphene. Phys. Rev. B 83, 165434 (2011).

Castro Neto, A. H., Guinea, F., Peres, N. M. R., Novoselov, K. S. & Geim, A. K. The electronic properties of graphene. Rev. Mod. Phys. 81, 109–162 (2009).

Zan, R. et al. Scanning tunnelling microscopy of suspended graphene. Nanoscale 4, 3065–3068 (2012).

Eder, F. R. et al. Probing from both sides: reshaping the graphene landscape via face-to-face dual-probe microscopy. Nano Lett. 13, 1934–1940 (2013).

Klimov, N. N. et al. Electromechanical properties of graphene drumheads. Science 336, 1557–1561 (2012).

Mashoff, T. et al. Bistability and oscillatory motion of natural nanomembranes appearing within monolayer graphene on silicon dioxide. Nano Lett. 10, 461–465 (2010).

Xu, P. et al. Atomic control of strain in freestanding graphene. Phys. Rev. B 85, 121406(R) (2012).

Sadeghi, A. et al. Multiscale approach for simulations of Kelvin probe force microscopy with atomic resolution. Phys. Rev. B 86, 075407 (2012).

Flores, F., Echenique, P. M. & Ritchie, R. H. Energy dissipation processes in scanning tunneling microscopy. Phys. Rev. B 34, 2899–2902 (1986).

Los, J. H., Katsnelson, M. I., Yazyev, O. V., Zakharchenko, K. V. & Fasolino, A. Scaling properties of flexible membranes from atomistic simulations: application to graphene. Phys. Rev. B 80, 121405(R) (2009).

Marconi, U. M. B., Puglisi, A., Rondoni, L. & Vulpiani, A. Fluctuation-dissipation: response theory in statistical physics. Phys. Rep. 461, 111–195 (2008).

Seol, J. H. et al. Two-dimensional phonon transport in supported graphene. Science 328, 213–216 (2010).

Mariani, E. & von Oppen, F. Flexural phonons in free-standing graphene. Phys. Rev. Lett. 100, 076801 (2008).

Bonini, N., Lazzeri, M., Marzari, N. & Mauri, F. Phonon anharmonicities in graphite and graphene. Phys. Rev. Lett. 99, 176802 (2007).

Chen, C. Graphene NanoElectroMechanical Resonators and Oscillators Ph.D. Thesis. Columbia University (2013).

Landau, L. D. & Lifshitz, E. M. Theory of Elasticity Pergamon Press: Oxford, (1970).

Zakharchenko, K. V., Katsnelson, M. I. & Fasolino, A. Finite temperature lattice properties of graphene beyond the quasiharmonic approximation. Phys. Rev. Lett. 102, 046808 (2009).

de Andres, P. L., Guinea, F. & Katsnelson, M. I. Density functional theory analysis of flexural modes, elastic constants, and corrugations in strained graphene. Phys. Rev. B 86, 245409 (2012).

Pogorelov, A. V. Bendings of Surfaces and Stability of Shells American Mathematical Society (1988).

Lindahl, N. et al. Determination of the bending rigidity of graphene via electrostatic actuation of buckled membranes. Nano Lett. 12, 3526–3531 (2012).

Reina, A. et al. Large area, few-layer graphene films on arbitrary substrates by chemical vapor deposition. Nano Lett. 9, 30–35 (2009).

Acknowledgements

This work was financially supported , in part, by the Office of Naval Research under grant N00014-10-1-0181, the National Science Foundation under grant DMR-0855358, the EU-Marie Curie IIF postdoc Fellowship/299855 (for M.N.-A.), the ESF-EuroGRAPHENE project CONGRAN, the Flemish Science Foundation (FWO-Vl) and the Methusalem Foundation of the Flemish Government.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

P.M.T. and P.X. devised the experiments. J.K.S., M.L.A., S.D.B., P.M.T. and P.X. performed the experiments and carried out data analysis. S.D.B. and M.L.A. made the figures. F.M.P, M.N.-A. and A.S. provided the theoretical work and supplementary material. All authors discussed the results and co-wrote the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Figures 1-3, Supplementary Notes 1-4 and Supplementary References (PDF 465 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Xu, P., Neek-Amal, M., Barber, S. et al. Unusual ultra-low-frequency fluctuations in freestanding graphene. Nat Commun 5, 3720 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms4720

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms4720

This article is cited by

-

Disorders in graphene: types, effects and control techniques—a review

Carbon Letters (2022)

-

Locomotion of the C60-based nanomachines on graphene surfaces

Scientific Reports (2021)

-

Three-dimensional surface topography of graphene by divergent beam electron diffraction

Nature Communications (2017)

-

Critical slowing down in purely elastic ‘snap-through’ instabilities

Nature Physics (2017)

-

Visualising the strain distribution in suspended two-dimensional materials under local deformation

Scientific Reports (2016)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.