Key Points

-

Describes the social and anthropological significance of intentional dental modifications.

-

Outlines an example of dental mutilation in India.

-

Facilitates anthropological comparison with classical' typologies.

Abstract

Intentional mutilation or modifications to human teeth hold anthropological and social significance. Studying them helps to understand past and present human behaviour from a geographic, cultural, religious and aesthetic perspective. Presented herein is the case of the skull of a male aged 20-25 years from Madurai (Tamil Nadu, India) with aesthetic dental mutilation on the two upper central incisors, originating from the Skull Collection of the Museum of Forensic Anthropology, Paleopathology and Criminal Studies of the School of Legal Medicine of Madrid. The mutilation consists of both an alteration of the contour of the crown and the inclusion of decorative elements on the labial surface of both teeth. Performed in this study is a radiographic analysis of the dental modifications as well as a paleopathological study of the mutilated teeth.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Although aesthetic odontology is a part of odontostomatology of relatively modern development, the concept of aesthetics in dentistry is quite ancient. The search for bodily beauty is as old as time. Polykleitos, Galen, Vitruvius and Leonardo da Vinci established their own ideals: these somatic evaluations have had the purpose of creating ideal types of man for both artistic and medical purposes.

Leon Bautista Alberti (1404-1472) and Vincenzo Danti (1530-1576) refused a standard. Emerging from these observations is the principle of variability which will come to replace the principle of constancy: the ideal shifts in its function as a rule, for creating a normal if not ideal – man, with individual features and expressions that have a beauty of their own. The ideals are thereby transformed from artistic to scientific, oriented by anatomical observations through a quantitative assessment of somatic features.

In today's world – so conscious of the importance of aesthetics and image – white, properly shaped, well-aligned teeth constitute the standard for beauty. In this ideal, those teeth which fit the standards for beauty are not only considered to be aesthetically pleasant, but are also an indicator of health, hygiene, and economic and cultural status, in addition to playing a clear role in self-esteem, social relations and the individual's sexuality.

Dental mutilation

The word 'mutilation' comes from the Latin mutilus, deformed, transformed. Mutilation or disfigurement of the body is traditionally associated with certain cultural or religious practices. Mutilations have an anthropological and social value, and studying them helps us to understand past and present human behaviour from a geographic, cultural, religious and aesthetic perspective.

Of all bodily mutilations, perhaps one of the most frequent is the mutilation of teeth. The authors prefer to refer to this as dental transformation or dental decoration, due to the pejorative connotation implicit in the term mutilation.1 In those societies where it is practised, dental mutilation is a distinguishing mark of high status, of belonging to a tribe or clan, or of beauty. Non-therapeutic dental mutilation is extremely common and varied. It consists of breaking, filing, sharpening, inlays, crown removal, avulsion, dyeing, colouring, changing position, piercing the teeth, etc.2,3,4 Alt, Rösing and Teschler-Nicola (1998) as well as Alt and Pichler (1998) have performed a complete classification of artificial modifications to human teeth, including sharpening, chipping, dental decoration (inlays or incrustations), ablation, whitening, dyeing, changes in position, amputation and germenectomy among these intentional dental mutilations.4,5

Dental mutilations are generally located on the six teeth in the antero-superior group, though cases have been documented of mutilation on the antero-inferior teeth, as well as on teeth in the premolar set.3,6,7 Dental mutilations on teeth in the molar set are truly uncommon. No dental mutilations have been documented on deciduous teeth.

Researchers have given various explanations for performing intentional modifications of teeth. Some authors claim that dental mutilation is a form of ornamentation (Rubín de la Borbolla, 1940; Romero, 1958; Fastlich, 1976); others point out that they are identifying marks for tribes (van Reenen, 1978 and 1986; Handler, 1994) or indicators of social status (Fastlich, 1948 and 1976).4,5,8,9,10 Religious or ritual reasons behind them also appear among the causes which authors attribute to the practice of dental mutilation.1,5,10,11

Dental mutilation has been studied extensively among populations – both current and primitive – in Sub-Saharan Africa and Mesoamerica6,7 due to their frequency, but they have also been observed to a lesser degree in populations of North America, South America, India, Southeast Asia, the Malaysian Archipelago, the Philippines, New Guinea, Japan, Australia and the Pacific Islands.1,2,12,13,14

Authors have classified the different types of dental mutilation in accordance with modification patterns. The classifications by Saville (1913) and Rubín de la Borbolla (1944) are classics, but the classification par excellence is that performed by Romero (1970, 1986), which defined seven basic types of dental mutilation based on the study of a collection of 1,212 teeth from the National Institute of Anthropology and History of Mexico. Romero divided each type of dental mutilation into at least five variants, resulting in a total of 59 different types of dental mutilation, classified in accordance with the nature of the alteration of the coronal contour, the inclusion of decorative details on the vestibular surfaces or a combination of both.2,3,12,13,15

These three classifications refer to dental mutilations in pre-Hispanic Mesoamerica. Tables of dental mutilation types have not been documented for populations in Sub-Saharan Africa or Southeast Asia or for aboriginal populations in Australia. In the existing bibliography, the classifications by Saville, Rubín de la Borbolla and Romero are used by the authors as a reference when defining the type of dental mutilation that affects the teeth of those specimens and populations for which no tables of mutilation types exist.1

Dental mutilation in India

Dental mutilation is unusual and uncommon in India. Among these populations, one can find techniques of dental sharpening and carving in the form of grooves on the labial faces, which are later dyed using various colouring substances or inlays. These patterns can also be found with some frequency among the Sunda populations of the Pacific.8,14

No tables of dental mutilation types have been documented for populations in India. In general, dental mutilation in Southeast Asia is of a notably aesthetic nature. Some populations consider the anterior teeth of human beings to be too similar to those of dogs, and therefore they are filed, sharpened, dyed or removed15,16 as a reaffirmation of the human essence and appearance. All of these beliefs in some way condition the practice of dental decoration; the evolution of the cosmogonic and spiritual explanation is reflected in the aesthetics of the smile, in the same way as occurred in art or literature; shifting from more primitive theriomorphism or zoomorphism (sharpening, polishing, avulsion, etc) to anthropomorphism (inlays, dyeing, colouring, etc).14,16,17

Bibliographically, the only described example of dental mutilation in India is that of Skeleton IIB- 33 from Burial Site no. 4 at Bimbethka, in the hills of Vindhya, India. It is also one of the few archaeological examples of dental mutilation described in South Asia.14 The specimen was discovered by V. M. Misra in 1977, and it was found with five other human burials attributed to the Indian Mesolithic (Late Stone Age) with an age of 10,000 to 2,500 years. The stratigraphic studies and those of the artefacts in Burial Site no. 4 suggest an approximate age of 8,000 years.12 Dental mutilation is still practised today in India, with transformation patterns in which grooves, cuts and chipping are performed on the labial and occlusal surfaces, as well as piercing and inlays of incrustations on the labial surface of the antero-superior set.12

Study of dental mutilation in a Tamil skull from the Museum of Forensic Anthropology (UCM)

Skull 254 from the Collection of the Museum of Forensic Anthropology, Paleopathology and Criminal Studies is the skull of a young male (20-25 years old) originating from Madurai, with unknown dating, but before the nineteenth century, the date when the original collection was created (Fig. 1).

Skull 254 belongs to the former Velasco Collection, which later came to form part of the museum's collection. The skulls from the Velasco Collection and a part of the skulls from the Olóriz Collection, as well as those contributed by Dr Reverte Coma, make up the current Collection of Skulls of the Museum of Forensic Anthropology, Paleopathology and Criminal Studies at the School of Medicine of the Universidad Complutense de Madrid. The remaining skulls in the Olóriz Collection belong to the collection of the Museum of Anatomy of the School of Medicine of the Universidad Complutense de Madrid.

a) Dental mutilations of Skull 254

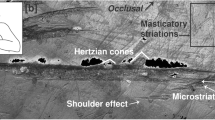

Skull 254 of the Collection of the Museum of Forensic Anthropology, Paleopathology and Criminal Studies displays combined mutilation11 consisting of dental sharpening and mesial and distal margins of the incisal edge and the carving of converging grooves in a triangular pattern, with polishing of the rhomboid surface created using these two techniques.

The dental sharpening affects the margins of both incisors from the medial-incisal third of the crown. From the bisector of the margins of the sharpenings, two grooves of little depth emerge, with a width of 1-1.5 mm (wedge-shaped), converging at the medial-cervical third of the crown. The combination of these two techniques gives rise to an area with a rhomboid shape that has been carefully polished (Figs 2-3). The enamel in the proximity of the carved grooves has been lost, possibly due to the force exerted during the dental transformation process or due to wear and tear as a result of weakening after the mutilation (Figs 2-3). The dental sharpening affects the dentine of the mesial and distal marginal crests of both teeth, which is exposed (Fig. 4). As can be inferred from the bibliographic studies, in general tooth fracturing is performed by applying a cutting object thereupon, which is hit with an object in the manner of a hammer. In order to carve or produce small fractures on a tooth, pieces of stone sharpened like a chisel are also used.11 Filing or polishing of teeth is performed using stones or abrasive powders.11

Up to now, the only known specimen representing dental mutilation in India was that described by Kennedy et al. in 1981.12

The dental mutilations present in Skull 254 cannot be encompassed into any of the mutilation type classifications existing in the literature.

b) Paleopathology of Skull 254

With a certain frequency, intentional dental modifications are associated with pathologies such as dental pulp resorption or periapical abscesses.1,15

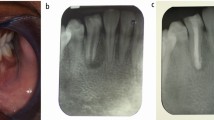

A radiological study has been performed on Skull 254 to study the status of the dental pulp in the mutilated teeth, as well as a study of the supporting bone tissue and apical bone. The radiological study consisted of frontal radiography (Fig. 5) and orthopantomography (Fig. 6), and show pulpar and periodontal involvement.

The radiographies show a retraction of pulp measuring 1.5 mm in tooth 1.1. In tooth 2.1, one can also see a retraction of pulp measuring approximately 2-3 mm and a periapical radiolucid area compatible with an abscess or periapical granuloma. The alveolar bone of 1.1 is normal. Tooth 2.1 displays vertical wedge-shaped reabsorption of the alveolar distal bone to the tooth of approximately 2 mm.

Conclusion

Dental mutilation is a very widespread practice which is associated with certain cultures, beliefs and aesthetic ideals. Tamil skull no. 254 from the Museum of Forensic Anthropology, Paleopathology and Criminal Studies at the School of Medicine of the Universidad Complutense de Madrid constitutes a unique piece among those with dental mutilation, due to the rarity of the casuistics of these intentional alterations in India, as well as the pattern of transformation, which cannot be defined using any of the classifications existing in the literature.

References

Milner G R, Larsen C S . Teeth as artefacts of human behaviour: intentional mutilation and accidental modification. In: Advances in dental anthropology, 1st ed. pp 357–378. New York: Wiley-Liss Inc, 1991.

Tiesler V, Ramírez M, Oliva I . Técnicas de decoración dental en México. Actual Arqueol 2005; 2: 18–24.

Tiesler V. Head shaping and dental decoration among the ancient Maya: archaeological and cultural aspects. Paper presented at 64th Meeting of the Society of American Archaeology. Chicago, 1999.

Alt K W, Rösing F W, Teschler-Nicola M. Dental anthropology: fundamentals, limits and prospects, 1st ed. New York: Springer-Verlag Wien, 1998.

Alt K W, Pichler S L . Artificial modifications of human teeth. In: Dental anthropology: fundamentals, limits and prospects, 1st ed. pp 386–415. New York: Springer-Verlag Wien, 1998.

Bautista J. Huellas de alteraciones culturales en el hombre prehispánico. Canindé 2003; 3: 37–58.

Del Río R B Las mutilaciones dentarias en Mesoamérica. Rev Asoc Dent Mex 2002; 59: 28–33.

Herrman N D, Benedix D C, Scott A M, Haskins V A . A brief comment of functional use of intentional filed teeth. Cueva de las Arañas Tooth Paper, 2007.

Handler J S, Corruccini R S . Dental mutilation in slaves of Barbados. J Interdiscipl Hist 1983; 14: 65–90.

Fitting W. Les mutilations dentaires dans le cadre des mutilations rituelles. Actual Odontostomatol 1989; 166: 191–203.

Dembo A, Imbelloni J . Deformaciones intencionales del cuerpo humano de carácter étnico, 1st ed. Buenos Aires: Ed. Humanior, 1938.

Kennedy K A R, Misra V N, Burrow C B . Dental mutilation in prehistoric India. Curr Anthropol 1981; 22: 285–286.

Saville M H. Precolumbian decoration of the teeth in Ecuador. With some account of the occurrence of the custom in other parts of North and South America. Am Anthropol 1913; 15: 377–394.

Jones A. Dental transfigurements in Borneo. Br Dent J 2001; 191: 98–102.

Fastlich S. Dental inlays and fillings among the ancient Mayas. J Hist Med 1962; 17: 392–401.

Fitton J S. A tooth ablation custom occurring in the Maldives. Br Dent J 1993; 23: 299–300.

Jones A. Kubangwa. Br Dent J 1988; 164: 225.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Refereed paper

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

González, E., Pérez, B., Sánchez, J. et al. Dental aesthetics as an expression of culture and ritual. Br Dent J 208, 77–80 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.2010.53

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.2010.53

This article is cited by

-

The dental complications of canine tooth bud removal in 2–12 years old children in Northwest Ethiopia

BMC Research Notes (2019)

-

Prevalence and impact of infant oral mutilation on dental occlusion and oral health-related quality of life among Kenyan adolescents from Maasai Mara

BMC Oral Health (2018)