Abstract

The neuregulin-1 (NRG1) gene is one of the best-validated risk genes for schizophrenia, and psychotic and bipolar disorders. The rs6994992 variant in the NRG1 promoter (SNP8NRG243177) is associated with altered frontal and temporal brain macrostructures and/or altered white matter density and integrity in schizophrenic adults, as well as healthy adults and neonates. However, the ages when these changes begin and whether neuroimaging phenotypes are associated with cognitive performance are not fully understood. Therefore, we investigated the association of the rs6994992 variant on developmental trajectories of brain macro- and microstructures, and their relationship with cognitive performance. A total of 972 healthy children aged 3–20 years had the genotype available for the NRG1-rs6994992 variant, and were evaluated with magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and neuropsychological tests. Age-by-NRG1-rs6994992 interactions and genotype effects were assessed using a general additive model regression methodology, covaried for scanner type, socioeconomic status, sex and genetic ancestry factors. Compared with the C-carriers, children with the TT-risk-alleles had subtle microscopic and macroscopic changes in brain development that emerge or reverse during adolescence, a period when many psychiatric disorders are manifested. TT-children at late adolescence showed a lower age-dependent forniceal volume and lower fractional anisotropy; however, both measures were associated with better episodic memory performance. To our knowledge, we provide the first multimodal imaging evidence that genetic variation in NRG1 is associated with age-related changes on brain development during typical childhood and adolescence, and delineated the altered patterns of development in multiple brain regions in children with the T-risk allele(s).

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The neuregulin-1 gene (NRG1) encodes many structural and functional isoforms through alternative promoter usage (type I–IV).1,2 These isoforms are involved in neuronal and glial development and synaptic plasticity.3, 4, 5, 6 Variants in NRG1 are associated with the diagnoses of schizophrenia and psychiatric disorders,7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17 and contribute to impaired brain functions in those patients.18,19 The rs6994992 (SNP8NRG243177) is one of the most studied genes associated with increased risk for schizophrenic and psychotic symptoms, as well as cognitive deficits in schizophrenics.20, 21, 22 This specific variant was also suggested to predict transition to psychosis in three independent cohorts with very high risk for psychosis.20,23,24 Moreover, genetic variations at rs6994992 altered the promoter activity of the type IV NRG1 isoform, which is expressed specifically in the brain and especially during the fetal period.25 Higher transcript levels of type IV NRG1 were also found in post-mortem brains of both healthy and schizophrenic adults with the TT-risk alleles.2 Variation at rs6994992 in the type IV NRG1 results in differential expression that may have a critical role in the schizophrenia and psychosis pathology.

Several magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) studies reported that NRG1-rs6994992 is associated with alterations in brain volumes and white matter integrity. In healthy adults, the T-risk allele is associated with smaller gray matter volumes in several gyri,26 higher white matter density in the right anterior internal capsule27 and lower white matter integrity in the left anterior thalamic radiation.22,26 Furthermore, adults with first-onset schizophrenia had T-allele dose-dependent increases in lateral ventricle volumes.28 Similar enlargements of the lateral ventricles along with altered developmental trajectories of gray and white matter were observed in TT-children (age 8–20 years) with childhood-onset schizophrenia compared with the C-carriers.29 In contrast, healthy neonates with the rs6994992-TT and parental psychiatric history (that is, bipolar disorder, depression, drug dependence/abuse) showed greater gray matter volumes in the frontal and temporal lobes than the C-carriers.30

Genetic influences on brain development can change with age31 and be modified by the environment.32 Therefore, we propose that modulation of the NRG1 expression through genetic variation at the rs6694992 influences brain development and may show a pleiotropic effect in different brain structures, as well as an antagonistic pleiotropic effect at different age during normal brain development. To our knowledge, no study evaluated whether the functional rs6994992 variant influences age-related brain development from early childhood to late adolescence in a large population and at micro- and macrostructural levels.

Cross-sectional studies across a large age span make it possible to evaluate age-dependent trajectories of brain development in relation to this particular genetic variation, and may improve our understanding of when these gene-related brain changes occur. The period of brain maturation in adolescence and early adulthood is a vulnerable time during which many mental illnesses are first expressed. Therefore, we investigated macro- and microstructural brain changes, using MRI, in a large cohort of healthy children aged 3–20 years. We focused on brain regions known to be associated with schizophrenia pathology, and reportedly affected by the rs6994992 variant (that is, mainly in the temporal, frontal and parietal lobes). Specifically, we hypothesized that compared with CC-alleles children, those with TT-alleles have differential age-dependent trajectories of micro- and macro-brain structures in these regions.

Furthermore, a recent meta-analysis found that schizophrenic patients consistently showed slower processing speed and poorer episodic memory than healthy controls.33 Therefore, we further evaluated whether the brain changes identified in the TT-children correlate with performance in these two domains.

Materials and methods

Data were obtained from the Pediatric Imaging Neurocognition and Genetic (PING) study database (http://ping.chd.ucsd.edu). PING is a cross-sectional normative data set from 1400 typically developing children aged 3–20 years that was collected across ten academic institutions in the United States. The data set includes whole genome single-nucleotide polymorphism genotype, developmental and neuropsychological assessments (NIH Toolbox) and high-resolution brain MRI. The human research protection programs and institutional review boards of the participating institutions approved the design, experiments and consents (oral and written) used for the PING study.

Subjects

A total of 972 children from the PING database were included in this study. Details on recruitment and subject characteristics were reported previously.34, 35, 36, 37 Informed consent was obtained either from the participants (⩾18 years old), or from their parents (<18 years of age) with child assent (7–17 years of age). Healthy children were screened to ensure that they had no self-reported or parent-reported history of major developmental, psychiatric or neurological disorders, brain injury or other medical conditions that would affect their brain development. Of the total, 250 children were additionally examined by a physician to ensure their healthy status before enrollment. Individuals born prematurely (<36 weeks gestational age), with significant prenatal drug or alcohol exposure or with contraindications for MRI (for example, metallic or electronic implants, claustrophobia, dental braces or pregnancy) were also excluded.

Genotyping, genotype imputation and genetic ancestry factor

Genomic DNA was extracted from saliva for genotyping using the Illumina Human660W-Quad BeadChip. Replication and quality control filters (that is, sample call rate >99%, call rates >95%, minor allele frequency >5%) were performed.38 To assess reproducibility, about 1% of the samples were genotyped in duplicates to compare genotypes. The rs6994992 variant located on chromosome 8 in the promoter region of the neuregulin-1 gene was imputed using MACH1.039 with the default settings and a quality control (R>0.5) for all individuals from the PING database as of 6 April 2013. To control for race/ethnicity on the outcome measures, genetic ancestry factors (GAFs) were estimated using a standard method that includes multidimensional scaling analysis and actual estimates of local ancestry in admixed populations (LAMP)40 as previously described.37

Image acquisition and image processing

The neuroimaging techniques, data acquisition and analyses were reported previously34, 35, 36 and are available on the PING website (http://ping.chd.ucsd.edu). Briefly, MRI was performed on ten 3 Tesla scanners from three manufacturers (Siemens, Erlangen, Germany; General Electric Medical, Milwaukee, WI, USA; two Philips Medical, Andover, MA, USA). On the Siemens scanners, MRI included a three-dimensional T1-weighted structural scan (TR/TE/TI=2170/2.78/1100 ms, 7-degree flip angle, 1.0 × 1.0 × 1.2 mm3 resolution, 8 min acquisition time), a T2-weighted volume and a set of diffusion-weighted scans (dual spin-echo echo-planar imaging, TR/TE=9500/91 s, 2 averages, 2.5 mm isotropic resolution, b-values=1000 s mm−2, 30 diffusion directions, 10 min acquisition time). Imaging protocols for the other scanner platforms closely matched those for the Siemens scanners. Prospective motion compensation41 was used for 74% of the T1-weighted scans at UCSD34 and 10.5% of those in Hawaii. After transferring the MRI data to the central processing site (UCSD) in DICOM format, all the images were automatically checked for protocol compliance on the basis of DICOM header information, and visually inspected for artifacts, including motion artifacts, signal inhomogeneities and ghosting. Scans rated as unacceptable on any rating were excluded from the study.

Image analyses were performed using a modified Freesurfer software suite (http://surfer.nmr.mgh.harvard.edu/) that is based on routine three-dimensional T1-weighted MRI volumes. FreeSurfer provides a method for automatic parcellation of the cortical surface, by which each location on the surface is assigned a neuroanatomical label on the basis of probabilistic information estimated from a manually labeled training set. Details on surface-based cortical reconstruction and subcortical volumetric segmentation were reported previously.34 Delineation and labeling of the white matter tracts were performed with the atlas-based method, AtlasTrack, using diffusion tensor images (DTIs), T1-weighted images and a probabilistic atlas of fiber tract locations and orientations.42 Validated for use in pediatric populations, AtlasTrack provides estimates for each tract the average mean diffusion, transverse and longitudinal diffusivity (TD and LD, respectively) and fractional anisotropy (FA).

Fiber tract volumes were calculated as the number of voxels with fiber probability estimates greater than 0.08.

Of the 972 children with rs6994992 imputed, all met quality criteria for cortical and subcortical measurements (thickness, area, volume), and 891 for DTI measures (81 children had DTI scans that did not meet the quality criteria, and were excluded from our analysis. Out of the 81 children, 43 TC/28 CC/10 TT, Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium χ2=0.48, P=0.49). However, as we controlled for socioeconomic status, sex, device number and GAF in all the statistical models, only 897 children were included in the cortical and subcortical analysis and 822 for the DTI analysis.

Episodic memory and processing speed

The NIH Toolbox Cognition Battery evaluates six major cognitive domains.37,43 We analyzed data from two tasks that represent the two domains implicated previously in schizophrenia: episodic memory (picture sequence memory test) and processing speed (pattern comparison processing speed test).33 The picture sequence memory test first presents a sequence of thematically related pictures to the child on a computer screen, and then requires the child to sort a sequence of reshuffled pictures back to the order that was shown previously. Six to 18 items in each sequence over three trials were presented depending on the child’s age (outcome: cumulative correct responses from a maximum of 18–48). For the pattern comparison processing speed task, the child has to determine whether two side-by-side pictures are similar by touching the smiley face or a sad face icon (ages 3–7 years), or a ‘yes’ or ‘no’ button (>7 years old), response on the screen (outcome: correct responses within the 90 s time limit).

Statistics

Statistical analyses were performed using a customized user interface for the PING database, called ‘Data Portal’ (https://ping-dataportal.ucsd.edu/). The ‘Data Portal’ enables statistical analysis of genotype- and genotype-by-age effects on neural architectural phenotypes (from the imaging data), and on relationships between neural phenotypes and neuropsychological measures using a general additive model44 as implemented by the R program (http://www.r-project.org/). General additive model is a multiple linear regression model that allows smooth functions of the predictor variables or covariates where the degree of smoothness is data-driven rather than pre-specified.44 Each statistical model used age as a smooth independent variable, and included a linear term for the genotype and a smooth interaction between age and genotype. Also, all models accounted for group differences in socioeconomic status (reflecting the highest parental education and household income), sex, GAF37 and study site. Cohen’s ƒ2 effect sizes were calculated to estimate the contribution of smooth age-by-genotype interactions. Cortical area and thickness were additionally adjusted for the total mean45 and subcortical volumes for intracranial volume. As cortical volumes are derived from regional areas and thickness, cortical volumes will not be reported to minimize multiple comparisons. For the vertex-based models, significance maps for cortical area and thickness were thresholded using the false discovery rate to correct for multiple comparisons at the 5% level.46 For the region of interest (ROI)-based models, 44 cortical structures (22 for each hemisphere) were considered in this study, including mainly the temporal, frontal and parietal lobes. To correct for multiple comparisons we used Holm-Bonferroni sequential correction that involved a stepwise rejective multiple test procedure, testing the most extreme P-value against the strictest criterion, and the others against progressively less strict criteria.47,48 Results on the areas or thickness of the cortical structures were then considered significant when adjusted P-values were<0.003 (α=0.05). Five subcortical ROIs and lateral ventricles showed no hemispheric differences and were averaged before evaluating genotype and age-by-genotype effects. The subcortical ROI results were considered significant when adjusted P-values<0.01 (α=0.05). Likewise, as the measures for the six white matter tracts that were shown to be abnormal in patients with schizophrenia or altered in those with the T-risk allele (ALIC, ATR, fornix, corpus callosum, superior longitudinal fasciculus, uncinate)20,27 showed no hemispheric differences, the values were averaged and adjusted P-values<0.01 (α=0.05) were considered significant.

Results

Participant characteristics

This study involved 972 children (mean age 12.07±4.97 years; 462 girls and 510 boys; Table 1). The genotype distribution for the rs6994992 variant across all subjects did not deviate from the Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium (P=0.38). Children in the three allele groups were similar in age, sex proportion, household income and parents/guardians’ highest level of occupation. However, the genotype groups differed by GAFs and the highest level of education of the parents/guardians. As expected, the frequency of TT genotype was lower than TC or CC genotypes in children with European and American Indian GAF and higher in children with East-Asia or with Central-Asia GAF. Hence, GAF was controlled for in each statistical model.

The rs6994992-T- allele is associated with altered development of subcortical structures

Consistent with prior reports,49,50 the volumes of pallidum, putamen, hippocampus and thalamus increased with age, but no genotype effects were found for these structures (Supplementary Table 1). On DTI, FA increased with age in basal ganglia structures (pallidum, caudate, putamen) and thalamus, but not in the hippocampus. Conversely, diffusivity (mean diffusion, LD and TD) generally showed age-related decreases in these subcortical structures. Age-by-genotype interactions were primarily found on FA in the basal ganglia. The age-related trajectories were significantly altered in the T-carriers for LD in the thalamus (Figure 1) and for TD in the putamen (Supplementary Figure 1) and pallidum (Figure 1). Furthermore, T-carriers had a higher FA in the pallidum than CC-carriers during adolescence but lower FA during younger childhood (Figure 1). Similar patterns were also found for the caudate and putamen (Supplementary Figure 1). Conversely, TD in these regions was higher in T-carriers than CC-carriers at younger ages, but showed a lower age-related TD during adolescence (Figure 1). Similar to schizophrenic adults,28 healthy TT-adolescents (>14 years of age) showed a trend for larger and steeper age-dependent increase in the lateral ventricles compared with C-carriers, leading to 37% larger estimated volumes at 20 years of age (Figure 1). Our statistical model explained 23.4% of the variance of the lateral ventricle volumes (age-by-genotype interaction, P=0.02, R2 (adjusted)=0.21, effect size (ƒ2) =0.266, power >0.90, α=0.05; a model excluding genotype explained only 11% of the variance).

Age-related differences in DTI metrics of subcortical structures (top row) and in lateral ventricle volume (bottom row). Percentages are expressed as increases (sign +) or decreases (sign −) in values between the TT-children (green) and the CC-children (blue). Black vertical arrows indicate when the age-by-genotype interactions emerge or reverse. The bottom right panel illustrates the location of subcortical structures of interest, as well as a statistical P-value map for FA generated with the ROI-based model. DTI, diffusion tensor image; FA, fractional anisotropy; LD, longitudinal diffusivity; ROI, region of interest; TD, transverse diffusivity.

The rs6994992-T-risk allele alters development of cortical morphometry

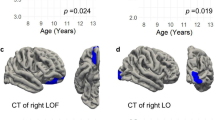

Figure 2 summarizes age-by-genotype interactions and genotype effects on developmental trajectories of the cortex using both vertex-based (Figure 2a) and ROI-based (Figure 2b) models. On both models, age-by-genotype interactions were found predominantly in the temporal, parietal and frontal lobes. For instance, the vertex-based model showed age-by-genotype interactions in thickness for the right supramarginal gyrus, the right superior temporal gyrus and the left fusiform, and in area for the middle frontal, inferior parietal right caudal anterior cingulate and left precuneus (Figure 2a). Most of the cortical phenotypes affected by the NRG1 variant emerged or reversed during adolescence (Supplementary Figures 2–5).

Summary of NRG1 genotype main effects and age-by-genotype interactions in cortical measures. (a) Statistical P-value maps showing significant interactions between smooth age and the three NRG1 genotypes (TT, TC and CC) in healthy children. The maps were generated from general additive models with cortical area and thickness as the dependent variable at each location (vertex) across the surface. Sex, device, GAF, SES were included as covariates, and findings were corrected for multiple comparisons with false discovery rate (FDR; α=0.05). The FDR threshold was obtained for left and right hemispheres combined and based on the cortical structures maps. (b) Table of NRG1-rs6994992 genotype differences and genotype-by-age interactions on cortical structures. The P-values (two-way analysis of covariance) of regions showing statistical differences with both the ROI-based and the vertex-based models are indicated in italic. The P-values that survived Holm–Bonferroni correction are in bold. GAF, genetic ancestry factor; ROI, region of interest; SES, socioeconomic status.

Three general patterns of age-by-genotype interaction were observed with the ROI-based models (Figure 3). The first pattern is exemplified by the rostral middle frontal gyrus surface area. Young TT-children did not exhibit genotype differences, but TT-adolescents showed a lesser age-related decline in area (Figure 3a) relative to C-carriers. This pattern was also observed for the area of the right frontal pole (Supplementary Figure 2).

Examples illustrating the different patterns of the age-by-genotype interactions on cortical area (obtained from the ROI-based model). The graphs exemplify age-related effects of NRG1 that emerge (a) or reverse (b and c) at adolescence, and a more complex age-by genotype interaction (d). Percentages are expressed as increases (sign +) or decreases (sign −) in values between the TT-children (green) and the CC-children (blue). Black vertical arrows indicate when the age-by-genotype interactions emerge or reverse. ROI, region of interest.

The second pattern involved a reversal of neuroimaging phenotypes with age, commonly with a crossing of trajectories during adolescence. For instance, in the right caudal middle frontal gyrus, young TT-children had a larger area than C-carriers, whereas TT-adolescents had a smaller area (Figure 3b). Similar interactions were found for the area of the lateral orbitofrontal cortex and the thickness of the left supramarginal gyrus (Supplementary Figures 3). Conversely, in the left caudal anterior cingulate, younger TT-children had smaller area (Figure 3c) and thickness (Supplementary Figure 3) than C-carriers, whereas the differences were reversed in adolescents. The right superior frontal gyrus exhibited this pattern on thickness, and the right inferior temporal gyrus on area (Supplementary Figure 3).

The third pattern was found for the right superior temporal gyrus, where the age-related curve of the TT-carriers for area followed a U-shape with a trough at 12.5 years of age, whereas a slightly inverted U-shape was observed in the C-carriers (Figure 3d). This pattern was also found for the thickness of the right inferior parietal cortex (Supplementary Figure 4).

Independent of age and compared with CC-carriers, TT-children had larger area of the right inferior parietal cortex (Supplementary Figure 5) and showed a steeper decrease in area of the left precuneus (Supplementary Figure 5).

The rs6994992-T-risk allele is associated with alterations in forniceal white matter

Among the white matter tracts evaluated (ALIC, ATR, Fornix, Corpus callosum, SLF), an age-by-genotype interaction was found only in the fornix volume and DTI metrics (Figure 4). TT-children showed inverted U-shapes in the growth of the volume (peaking at 11.5 years) and FA (peaking at 14 years) of the fornix. Conversely, CC-carriers showed continued growth or a plateau in both metrics during their second half of adolescence (Figures 4a and b). These differential developmental trajectories resulted in smaller volume (−6.1%) and lower FA (−3.4%) in TT-children compared with CC-children by age 20.

Associations between rs6994992-NRG1 genotype and fornix measures over age. The fornix tract showed age and NRG1 genotype dependent trajectories in volume (a) and FA (b). (c) Correlation between episodic memory task performance and forniceal metrics as a function of the NRG1 genotype. The center panel illustrates the location of the fornix. Percentages in the graphs are expressed as increases (sign +) or decreases (sign −) in values between the TT-children (green) and the CC-children (blue). Black vertical arrows indicate when the age-by-genotype interactions emerge or reverse. The P-values that survived Holm–Bonferroni correction are in bold. FA, fractional anisotropy; PSMT, picture sequence memory test.

Paradoxically, these TT-children with smaller volumes and lower FA of the fornix actually had higher picture sequence memory test scores (better episodic memory; Figure 4c). No significant correlations were found between pattern comparison processing speed test scores (processing speed) and brain imaging measures in the fornix.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first demonstration that the functional genetic variant rs6994992 in the NRG1 gene is associated with both microscopic and macroscopic alterations in brain development of typically developing healthy children and adolescents. Although the changes are subtle, some of our findings on cortical structures are consistent with those reported in neonates with high familial risk for psychosis30 and in schizophrenic adults and adolescents.26, 27, 28 This is also the first report to show that most of the NRG1-rs6994992 effects on neuroimaging phenotypes emerge or reverse during adolescence. Therefore, the neuroimaging phenotypes associated with this risk gene appear to evolve coincidentally with mental disorders that often emerge during adolescence, most likely due to the differential expression of the type IV NRG1 mediated by variation at rs6994992.

The NRG1-rs6994992 variant is located in the alternative promoter region of type IV NRG1, and those with the TT-alleles produce higher transcript levels (up to 40% higher) of the type IV NRG1 than those with the CC-alleles, as shown in the post-mortem brains of both healthy and schizophrenic individuals.2 Likewise, the NRG1 promoter of the T-alleles is 65% more active than that of C-alleles in cell cultures.25 Therefore, rs6994992-TT children might produce more type IV NRG1 during brain development, which could lead to structural changes that ultimately increase the risk for mental disorders. However, the associated cellular mediators on structural MRI measures are unknown, and thus the molecular mechanism implicating type IV NRG1 remains speculative. Nevertheless, assessing how this variant affects brain development and whether the expression of type IV NRG1 through this variation is involved in this process may lead to new therapeutic targets.

On cortical structures, both vertex- and ROI-based analyses showed that genetic variation at rs6994992 is associated primarily with alterations in the growth trajectories of the cortical area, and hence volume, in the frontal, temporal and parietal lobes. Our findings are consistent with a prior study that showed TT-allele children with childhood-onset schizophrenia had greater total gray matter volume and changes in shapes and forms of the frontal, temporal and parietal lobes.29 Similar to our study, TT-neonates with high familial risk for psychosis had larger volumes than C-carriers primarily in the frontal and temporal lobes, and smaller volumes in several smaller regions across the brain.30 In addition, our study demonstrates that variation at rs6994992 affects regions that are often associated with volume loss in adolescents with ultra-high risk for psychosis, such as that in the left caudal anterior cingulate51 and left precuneus.52 Replicating findings of rs6994992 effects on cortical structures in such a large cohort of typically developing children strongly supports the biological relevance of the gene’s effects on newly identified regions involved in psychosis, such as the right inferior parietal gyrus or the supramarginal gyrus. However, these prior studies did not investigate age-by-NRG1 genotype interactions, perhaps due to the smaller sample size and narrower age ranges.

Larger ventricular volume in TT-carriers compared with C-carriers started in adolescence. Although the statistical significance for this trait is borderline (P=0.02), similar ventricular enlargement associated with the rs6994992 variant was reported in schizophrenic adults and unaffected relatives,28 as well as in children with childhood-onset schizophrenia (8–20 years of age).29

On subcortical structures, we did not find smaller basal ganglia and thalamus volumes as reported in TT-neonates.30 However, NRG1-related alterations were observed on striatal FA, an indicator of white matter coherence and axonal organization,53 and on TD, which may reflect myelination or glial cell morphology.54, 55, 56 Therefore, the rs6994992 variant may affect white matter through myelination rather than axonal integrity, since the LD was normal.55,57 In contrast, the rs6994992 variant may affect the axonal integrity or extracellular space of the thalamus, as indicated by changes in both the LD and FA. Again, these subcortical changes typically emerged at adolescence. These results highlight the pleiotropic role of the rs6994992-NRG1 T-risk allele on brain development, and suggest that peripubertal factors, such as hormones or environment, might further impact the gene expression.

The developmental trajectories of FA, mean diffusion and volume of the fornix in the PING cohort resemble those in another smaller healthy cohort (5–83 years of age) that showed inverted U-shaped curves on forniceal FA and volumes, peaking near age 20 years.58 The magnitude of declines in forniceal volume and FA in our TT-children is also comparable with the findings in that cohort,58 suggesting an accelerated aging effect of NRG1-rs6994992 T-allele on fornix metrics.

As reduced fornix volume was found in both schizophrenic adolescents59 and adults,60 our finding of smaller fornix in TT-risk children suggests a presymptomatic endophenotype. The emergence of these alterations during adolescence suggests a possible association with hormonal changes that occur during puberty. However, longitudinal follow-up studies are required to assess whether these children will develop psychiatric symptoms or what factors might trigger the onset of symptoms.

Finally, smaller fornix volume in our TT-children was associated with better episodic memory (picture sequence memory test), which is opposite to the poorer episodic memory found in schizophrenics.33 In contrast, our findings suggest a positive impact of the rs6994992 variant on neuropsychological performance and are consistent with those reported by Keri.61 The author described that the TT-carriers had the highest creative-thinking scores in healthy adults with high intellectual and academic performance. Creative thinking and episodic memory were previously reported to be related to psychosis.20,23,24 The better performance in the healthy subjects may reflect an antagonistic pleiotropy effect, with better performance at younger age and poorer performance with aging, in these individuals with the T-risk allele. Nevertheless, abnormalities in fornix volume and diffusivity often precede the clinical deterioration of cognitive function and episodic memory in schizophrenics.62, 63, 64 Therefore, our results further support the hypothesis that NRG1-TT alleles confer risk for the schizophrenia phenotype via lesser myelination and atrophy of the white matter, especially the fornix.

Limitations

A potential limitation with a large scale study is the wide diversity in genetic backgrounds of the participants. However, a major strength of the PING data set is that the study was designed to detect a genetic variant effect size of 0.1 with a power >0.99 and a sample size of at least 800 children, assuming a total of seven independent variables and a type I error rate of 1 × 10−7. However, findings from the PING study are somewhat limited by the cross-sectional study design. For instance, outcome measures reflect changes in neurophenotypes of the children at the time of the scan, although the phenotype could have been present earlier. Future longitudinal studies are needed to validate the role of the type IV NRG1 in neurodevelopmental trajectories, aging and pathology. To minimize erroneous conclusions about the effects of age and the NRG1-rs6994992rs6994992 variant on changes in brain structures over time, all analyses included fixed traits such as sex, ethnicity and socioeconomic status as covariates. Another potential limitation is the possible influence of subclinical disease on brain measures in some of these children, despite our efforts to include only healthy children by careful screening and evaluations. As schizophrenia and psychosis may develop subclinically years before clinical symptoms are detectable, long-term follow-up examinations are needed to determine whether some of these individuals will develop these clinical disorders.

Conclusion

The rs6994992-polymorphism in the NRG1 gene is associated with divergent age-related changes in gray and white matter regions. Those changes are expressed during adolescence, a period when symptoms for neuropsychiatric disorder commonly arise. Our study bridges the existing gaps and validates prior smaller studies on the effects of rs6994992-NRG1 on developmental trajectories during childhood and adolescence, and ties in with prior findings from neonates through adulthood. Future research on the molecular mechanism underlying the roles of NRG1 and the genes involved in its pathway, such as ERBB4, on brain development and cognitive performance may ultimately lead to early detection and improved treatment of schizophrenia and psychotic disorders.

References

Steinthorsdottir V, Stefansson H, Ghosh S, Birgisdottir B, Bjornsdottir S, Fasquel AC et al. Multiple novel transcription initiation sites for NRG1. Gene 2004; 342: 97–105.

Law AJ, Lipska BK, Weickert CS, Hyde TM, Straub RE, Hashimoto R et al. Neuregulin 1 transcripts are differentially expressed in schizophrenia and regulated by 5' SNPs associated with the disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2006; 103: 6747–6752.

Chen S, Velardez MO, Warot X, Yu ZX, Miller SJ, Cros D et al. Neuregulin 1-erbB signaling is necessary for normal myelination and sensory function. J Neurosci 2006; 26: 3079–3086.

Kwon OB, Paredes D, Gonzalez CM, Neddens J, Hernandez L, Vullhorst D et al. Neuregulin-1 regulates LTP at CA1 hippocampal synapses through activation of dopamine D4 receptors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2008; 105: 15587–15592.

Mei L, Xiong WC . Neuregulin 1 in neural development, synaptic plasticity and schizophrenia. Nat Rev Neurosci 2008; 9: 437–452.

Shamir A, Kwon OB, Karavanova I, Vullhorst D, Leiva-Salcedo E, Janssen MJ et al. The importance of the NRG-1/ErbB4 pathway for synaptic plasticity and behaviors associated with psychiatric disorders. J Neurosci 2012; 32: 2988–2997.

Stefansson H, Sigurdsson E, Steinthorsdottir V, Bjornsdottir S, Sigmundsson T, Ghosh S et al. Neuregulin 1 and susceptibility to schizophrenia. Am J Hum Genet 2002; 71: 877–892.

Stefansson H, Sarginson J, Kong A, Yates P, Steinthorsdottir V, Gudfinnsson E et al. Association of neuregulin 1 with schizophrenia confirmed in a Scottish population. Am J Hum Genet 2003; 72: 83–87.

Williams NM, Preece A, Spurlock G, Norton N, Williams HJ, Zammit S et al. Support for genetic variation in neuregulin 1 and susceptibility to schizophrenia. Mol Psychiatry 2003; 8: 485–487.

Yang JZ, Si TM, Ruan Y, Ling YS, Han YH, Wang XL et al. Association study of neuregulin 1 gene with schizophrenia. Mol Psychiatry 2003; 8: 706–709.

Bakker SC, Hoogendoorn ML, Selten JP, Verduijn W, Pearson PL, Sinke RJ et al. Neuregulin 1: genetic support for schizophrenia subtypes. Mol Psychiatry 2004; 9: 1061–1063.

Tang JX, Chen WY, He G, Zhou J, Gu NF, Feng GY et al. Polymorphisms within 5' end of the Neuregulin 1 gene are genetically associated with schizophrenia in the Chinese population. Mol Psychiatry 2004; 9: 11–12.

Corvin AP, Morris DW, McGhee K, Schwaiger S, Scully P, Quinn J et al. Confirmation and refinement of an 'at-risk' haplotype for schizophrenia suggests the EST cluster, Hs.97362, as a potential susceptibility gene at the Neuregulin-1 locus. Mol Psychiatry 2004; 9: 208–213.

Li T, Stefansson H, Gudfinnsson E, Cai G, Liu X, Murray RM et al. Identification of a novel neuregulin 1 at-risk haplotype in Han schizophrenia Chinese patients, but no association with the Icelandic/Scottish risk haplotype. Mol Psychiatry 2004; 9: 698–704.

Munafo MR, Thiselton DL, Clark TG, Flint J . Association of the NRG1 gene and schizophrenia: a meta-analysis. Mol Psychiatry 2006; 11: 539–546.

Georgieva L, Dimitrova A, Ivanov D, Nikolov I, Williams NM, Grozeva D et al. Support for neuregulin 1 as a susceptibility gene for bipolar disorder and schizophrenia. Biol Psychiatry 2008; 64: 419–427.

Walker RM, Christoforou A, Thomson PA, McGhee KA, Maclean A, Muhleisen TW et al. Association analysis of Neuregulin 1 candidate regions in schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. Neurosci Lett 2010; 478: 9–13.

Stephan KE, Baldeweg T, Friston KJ . Synaptic plasticity and dysconnection in schizophrenia. Biol Psychiatry 2006; 59: 929–939.

Shamir A, Buonanno A . Molecular and cellular characterization of Neuregulin-1 type IV isoforms. J Neurochem 2010; 113: 1163–1176.

Hall J, Whalley HC, Job DE, Baig BJ, McIntosh AM, Evans KL et al. A neuregulin 1 variant associated with abnormal cortical function and psychotic symptoms. Nat Neurosci 2006; 9: 1477–1478.

Stefanis NC, Trikalinos TA, Avramopoulos D, Smyrnis N, Evdokimidis I, Ntzani EE et al. Impact of schizophrenia candidate genes on schizotypy and cognitive endophenotypes at the population level. Biol Psychiatry 2007; 62: 784–792.

Sprooten E, Lymer GK, Munoz Maniega S, McKirdy J, Clayden JD, Bastin ME et al. The relationship of anterior thalamic radiation integrity to psychosis risk associated neuregulin-1 variants. Mol Psychiatry 2009; 14 3: 233.

Keri S, Kiss I, Seres I, Kelemen O . A polymorphism of the neuregulin 1 gene (SNP8NRG243177/rs6994992) affects reactivity to expressed emotion in schizophrenia. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet 2009; 150B: 418–420.

Bousman CA, Yung AR, Pantelis C, Ellis JA, Chavez RA, Nelson B et al. Effects of NRG1 and DAOA genetic variation on transition to psychosis in individuals at ultra-high risk for psychosis. Transl Psychiatry 2013; 3: e251.

Tan W, Wang Y, Gold B, Chen J, Dean M, Harrison PJ et al. Molecular cloning of a brain-specific, developmentally regulated neuregulin 1 (NRG1) isoform and identification of a functional promoter variant associated with schizophrenia. J Biol Chem 2007; 282: 24343–24351.

Barnes A, Isohanni M, Barnett JH, Pietilainen O, Veijola J, Miettunen J et al. Neuregulin-1 genotype is associated with structural differences in the normal human brain. Neuroimage 2012; 59: 2057–2061.

McIntosh AM, Moorhead TW, Job D, Lymer GK, Munoz Maniega S, McKirdy J et al. The effects of a neuregulin 1 variant on white matter density and integrity. Mol Psychiatry 2008; 13: 1054–1059.

Mata I, Perez-Iglesias R, Roiz-Santianez R, Tordesillas-Gutierrez D, Gonzalez-Mandly A, Vazquez-Barquero JL et al. A neuregulin 1 variant is associated with increased lateral ventricle volume in patients with first-episode schizophrenia. Biol Psychiatry 2009; 65: 535–540.

Addington AM, Gornick MC, Shaw P, Seal J, Gogtay N, Greenstein D et al. Neuregulin 1 (8p12) and childhood-onset schizophrenia: susceptibility haplotypes for diagnosis and brain developmental trajectories. Mol Psychiatry 2007; 12: 195–205.

Knickmeyer RC, Wang J, Zhu H, Geng X, Woolson S, Hamer RM et al. Common variants in psychiatric risk genes predict brain structure at birth. Cereb Cortex 2013; 24: 1230–1246.

Douet V, Chang L, Cloak C, Ernst T . Genetic influences on brain developmental trajectories on neuroimaging studies: from infancy to young adulthood. Brain Imaging Behav 2014; 8: 234–250.

Lenroot RK, Giedd JN . The changing impact of genes and environment on brain development during childhood and adolescence: initial findings from a neuroimaging study of pediatric twins. Dev Psychopathol 2008; 20: 1161–1175.

Schaefer J, Giangrande E, Weinberger DR, Dickinson D . The global cognitive impairment in schizophrenia: consistent over decades and around the world. Schizophr Res 2013; 150: 42–50.

Brown TT, Kuperman JM, Chung Y, Erhart M, McCabe C, Hagler DJ Jr et al. Neuroanatomical assessment of biological maturity. Curr Biol 2012; 22: 1693–1698.

Fjell AM, Walhovd KB, Brown TT, Kuperman JM, Chung Y, Hagler DJ Jr et al. Multimodal imaging of the self-regulating developing brain. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2012; 109: 19620–19625.

Walhovd KB, Fjell AM, Brown TT, Kuperman JM, Chung Y, Hagler DJ Jr et al. Long-term influence of normal variation in neonatal characteristics on human brain development. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2012; 109: 20089–20094.

Akshoomoff N, Newman E, Thompson WK, McCabe C, Bloss CS, Chang L, Amaral DG et al. The NIH toolbox cognition battery:results from a large normative developmental sample (PING). Neuropsychology 2013; 28: 1–10.

Bakken TE, Roddey JC, Djurovic S, Akshoomoff N, Amaral DG, Bloss CS et al. Association of common genetic variants in GPCPD1 with scaling of visual cortical surface area in humans. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2012; 109: 3985–3990.

Zaitlen N, Kang HM, Eskin E, Halperin E . Leveraging the HapMap correlation structure in association studies. Am J Hum Genet 2007; 80: 683–691.

Sankararaman S, Sridhar S, Kimmel G, Halperin E . Estimating local ancestry in admixed populations. Am J Hum Genet 2008; 82: 290–303.

White N, Roddey C, Shankaranarayanan A, Han E, Rettmann D, Santos J et al. PROMO: Real-time prospective motion correction in MRI using image-based tracking. Magn Reson Med 2010; 63: 91–105.

Fischl B, Dale AM . Measuring the thickness of the human cerebral cortex from magnetic resonance images. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2000; 97: 11050–11055.

Weintraub S, Dikmen SS, Heaton RK, Tulsky DS, Zelazo PD, Bauer PJ et al. Cognition assessment using the NIH Toolbox. Neurology 2013; 80: S54–S64.

Tibshirani RJ, Hastie TJ . Generalized additive model. Stat Sci 1986; 1: 297–318.

Eyler LT, Chen CH, Panizzon MS, Fennema-Notestine C, Neale MC, Jak A et al. A comparison of heritability maps of cortical surface area and thickness and the influence of adjustment for whole brain measures: a magnetic resonance imaging twin study. Twin Res Hum Genet 2012; 15: 304–314.

Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y . Controlling the false discovery rate: a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J R Statist Soc 1995; 57: 289–300.

Sture H . A simple sequentially rejective multiple test procedure. Scand J Stat Theory Appl 1979; 6: 65–70.

Aickin M, Gensler H . Adjusting for multiple testing when reporting research results: the Bonferroni vs Holm methods. Am J Public Health 1996; 86: 726–728.

Giedd JN, Vaituzis AC, Hamburger SD, Lange N, Rajapakse JC, Kaysen D et al. Quantitative MRI of the temporal lobe, amygdala, and hippocampus in normal human development: ages 4-18 years. J Comp Neurol 1996; 366: 223–230.

Lenroot RK, Giedd JN . Brain development in children and adolescents: insights from anatomical magnetic resonance imaging. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 2006; 30: 718–729.

Rothlisberger M, Riecher-Rossler A, Aston J, Fusar-Poli P, Radu EW, Borgwardt S . Cingulate volume abnormalities in emerging psychosis. Curr Pharm Des 2012; 18: 495–504.

Ziermans TB, Schothorst PF, Schnack HG, Koolschijn PC, Kahn RS, van Engeland H et al. Progressive structural brain changes during development of psychosis. Schizophr Bull 2012; 38: 519–530.

Pierpaoli C, Basser PJ . Toward a quantitative assessment of diffusion anisotropy. Magn Reson Med 1996; 36: 893–906.

Song SK, Sun SW, Ramsbottom MJ, Chang C, Russell J, Cross AH . Dysmyelination revealed through MRI as increased radial (but unchanged axial) diffusion of water. Neuroimage 2002; 17: 1429–1436.

Song SK, Sun SW, Ju WK, Lin SJ, Cross AH, Neufeld AH . Diffusion tensor imaging detects and differentiates axon and myelin degeneration in mouse optic nerve after retinal ischemia. Neuroimage 2003; 20: 1714–1722.

Song SK, Yoshino J, Le TQ, Lin SJ, Sun SW, Cross AH et al. Demyelination increases radial diffusivity in corpus callosum of mouse brain. Neuroimage 2005; 26: 132–140.

Budde MD, Kim JH, Liang HF, Schmidt RE, Russell JH, Cross AH et al. Toward accurate diagnosis of white matter pathology using diffusion tensor imaging. Magn Reson Med 2007; 57: 688–695.

Lebel C, Gee M, Camicioli R, Wieler M, Martin W, Beaulieu C . Diffusion tensor imaging of white matter tract evolution over the lifespan. Neuroimage 2012; 60: 340–352.

Kendi M, Kendi AT, Lehericy S, Ducros M, Lim KO, Ugurbil K et al. Structural and diffusion tensor imaging of the fornix in childhood- and adolescent-onset schizophrenia. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2008; 47: 826–832.

Kuroki N, Shenton ME, Salisbury DF, Hirayasu Y, Onitsuka T, Ersner-Hershfield H et al. Middle and inferior temporal gyrus gray matter volume abnormalities in first-episode schizophrenia: an MRI study. Am J Psychiatry 2006; 163: 2103–2110.

Keri S . Genes for psychosis and creativity: a promoter polymorphism of the neuregulin 1 gene is related to creativity in people with high intellectual achievement. Psychol Sci 2009; 20: 1070–1073.

Fletcher E, Raman M, Huebner P, Liu A, Mungas D, Carmichael O et al. Loss of Fornix White Matter Volume as a Predictor of Cognitive Impairment in Cognitively Normal Elderly Individuals. JAMA Neurol 2013; 70: 1389–1395.

Koenig KA, Sakaie KE, Lowe MJ, Lin J, Stone L, Bermel RA et al. High spatial and angular resolution diffusion-weighted imaging reveals forniceal damage related to memory impairment. Magn Reson Imaging 2013; 31: 695–699.

Zhuang L, Sachdev PS, Trollor JN, Reppermund S, Kochan NA, Brodaty H et al. Microstructural white matter changes, not hippocampal atrophy, detect early amnestic mild cognitive impairment. PloS One 2013; 8: e58887.

Acknowledgements

We thank all of the children and their families that have participated in our study, the physicians who referred some of the participants and all the technical staff from the research teams in the PING consortium. A particular thanks to Dr TT Brown for his assistance with the manuscript revision. This study was supported by the grants RC2-DA29475, 2K24-DA016170, U54NS56883, G12-MD007601.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Supplementary Information accompanies the paper on the Translational Psychiatry website

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Douet, V., Chang, L., Pritchett, A. et al. Schizophrenia-risk variant rs6994992 in the neuregulin-1 gene on brain developmental trajectories in typically developing children. Transl Psychiatry 4, e392 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1038/tp.2014.41

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/tp.2014.41

This article is cited by

-

Disruptions in white matter microstructure associated with impaired visual associative memory in schizophrenia-spectrum illness

European Archives of Psychiatry and Clinical Neuroscience (2021)

-

Dyslexia and language impairment associated genetic markers influence cortical thickness and white matter in typically developing children

Brain Imaging and Behavior (2016)

-

ERBB4 polymorphism and family history of psychiatric disorders on age-related cortical changes in healthy children

Brain Imaging and Behavior (2015)