Abstract

Internet psychological interventions are efficacious and may reduce traditional access barriers. No studies have evaluated whether any sampling bias exists in these trials that may limit the translation of the results of these trials into real-world application. We identified 7999 potentially eligible trial participants from a community-based health cohort study and invited them to participate in a randomized controlled trial of an online cognitive behavioural therapy programme for people with depression. We compared those who consented to being assessed for trial inclusion with nonconsenters on demographic, clinical and behavioural indicators captured in the health study. Any potentially biasing factors were then assessed for their association with depression outcome among trial participants to evaluate the existence of sampling bias. Of the 35 health survey variables explored, only 4 were independently associated with higher likelihood of consenting—female sex (odds ratio (OR) 1.11, 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.05–1.19), speaking English at home (OR 1.48, 95% CI 1.15–1.90) higher education (OR 1.67, 95% CI 1.46–1.92) and a prior diagnosis of depression (OR 1.37, 95% CI 1.22–1.55). The multivariate model accounted for limited variance (C-statistic 0.6) in explaining participation. These four factors were not significantly associated with either the primary trial outcome measure or any differential impact by intervention arm. This demonstrates that, among eligible trial participants, few factors were associated with the consent to participate. There was no indication that such self-selection biased the trial results or would limit the generalizability and translation into a public or clinical setting.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

An increasing number of studies have demonstrated that internet-delivered, or online, health interventions for depression and anxiety are both efficacious,1, 2, 3, 4, 5 and can be delivered to a population on a large scale.1, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10 These interventions have the potential to overcome traditional access barriers as they can be available anytime to individuals at low cost, and without waiting lists that are common for traditional face-to-face interventions. The relative user anonymity of these interventions may also appeal to people who may not otherwise access help and thus may increase help seeking.11

The value of online interventions or internet interventions has been recognized at policy level internationally. For instance, guidelines from the United Kingdom’s National Health Service (NHS),12, 13 the Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN)14 and the Department of Veteran’s Affairs in the United States15 have endorsed online interventions as part of stepped care management of depression. It seems likely that other countries will follow in the near future as further studies become available.

However, a limitation of randomized controlled trials upon which evidence is based is the potential for sampling bias to arise from the inclusion of only a minority of the intended population participating. This bias may systematically limit the generalizability of the trial results and translational into clinical use. This raises uncertainty regarding the impact of the intervention on the more diverse or complex population seen in clinical practice.

The two main sources of sampling bias are the selection biases arising from rigorously defined inclusion and exclusion criteria and those from self-selection into the study. In terms of the former, Wisniewski et al.16 found that only 22.2% of people likely to be prescribed antidepressants would have met the inclusion criteria for an antidepressant phase III trial. More recently, Van der Lem et al.17 found that of patients deemed to have a major depressive disorder, suitable for antidepressant treatment in clinical practice, only 17–25% would have met inclusion criteria for efficacy trials. When explored further, those who did meet trial inclusion criteria were more likely to be younger, more educated, employed and earning a higher income, married and of Caucasian descent. Their illness was also likely to be less severe with a shorter average duration, fewer anxiety or atypical symptoms and a lower number of prior suicide attempts,16 indicating that selection may bias participants to those more likely to recover.

Participation may be prone to self-selection bias that can threaten both the internal18 and external validity of the study.19 Self-selection can generate a difficult to mitigate bias, as there is often little or no information upon those not volunteering to participate in the study. In observational studies, previous work has indicated that those who choose not to participate in research surveys are more likely to have poorer psychological20, 21 and physical health20, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26 than those who participate. Conversely, those who do participate are more likely to be younger,20, 24, 27 more educated,22, 24, 26 female,22, 23, 27 of higher socioeconomic status26, 27 and married.23, 26, 28, 29 Such demographic factors significantly affect depression treatment outcome: lower levels of baseline dysfunction and illness duration,30, 31, 32 being younger,32 having higher levels of education33, 34 and income,33, 34, 35 not living alone,30, 31, 34 having a ‘good’ employment status30, 34 and having higher expectations of improvement32 are all associated with better outcomes across treatment modalities.32

The aim of this study was to (1) identify the factors associated with self-selection of eligible trial participants recruited from a large community health cohort study into a randomized controlled trial of an online depression treatment trial and (2) evaluate whether these factors were associated with outcome and thus potentially a source of sampling bias.

Materials and methods

Cardiovascular Risk E-couch Depression Outcome (CREDO) is a randomized, double-blind, parallel, attention-controlled, internet-delivered trial targeting depressive symptoms in those with cardiovascular disease or risk factors. The trial protocol been described in detail elsewhere.36

Participants

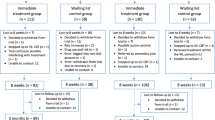

Participants were recruited from the 45 and Up Study,37 a longitudinal study of health and ageing, which has been shown to be reasonably representative of the state of New South Wales, Australia, on a number of key indices.38 Potential participants from the 45 and Up Study population pool were selected for invitation to be assessed for trial eligibility if they were aged between 45 and 75 years, had provided a valid email address, had self-reported significant risk factors for, or a history of, cardiovascular disease and had screened positive for at least ‘moderate’ psychological distress on the Kessler 10 scale (K10)39, 40 during the 45 and Up Study baseline data collection. These 7999 potential participants identified were approached via email. If the individuals consented to be assessed for trial inclusion they were directed to the CREDO trial website where a more rigorous evaluation took place to ascertain full trial inclusion and exclusion criteria including the presence of current depressive symptomology. Reminder emails were sent to participants who did not respond to the initial emailed invitation. Where participants failed to open either of these email invitations, as indicated by an electronic notification, a written invitation to participate was posted to them. Those whose emails ‘bounced back’ indicating no current email address were excluded from this study as they were ineligible to participate in the trial. From the initial and reminder emailed invitations to participate, 2914 (41.1%) emails were unopened and had not bounced back. Postal addresses were obtained for these potential participants and written invitations for participation were posted. This process identified 7086 participants who received a verified invitation to participate. The flow diagram for participant selection and recruitment can be viewed in Figure 1. Of the 7086 potential participants, 1885 (26.6%) provided consent to be assessed for trial inclusion and exclusion criteria.

We compared those who consented with nonconsenters (n=5201) on a range of a priori demographic, health and behavioural indices based on the predictors found in the self-selection bias literature and variables thought to be predictive of help-seeking behaviours. These data were obtained from the 45 and Up Study baseline health survey from which these participants were selected.

Potential sampling bias measures in health survey

Data analyses were completed using PASW computer software package version 18.0 (SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL, USA). Several variables were recoded for ease of analysis. For all potential participants (n=7086), ‘Country of birth’ was recoded into ‘born in Australia’ versus ‘other’. Similarly, ‘Language spoken at home’ was recoded into ‘English’ versus ‘Other’. Level of education was recoded into a two-option variable of ‘School only’ (those who had completed ‘No school certificate or other qualification’, ‘School or intermediate certificate’ or ‘Higher school or leaving certificate’) versus any ‘Further education’. Marital status was combined to create a three-option variable of ‘currently in relationship’ (containing de facto or married), ‘previously in relationship’ (divorced, separated, or widowed) or single. Employment status was recoded to a variable with three options consisting of working (full-time or part-time paid employment), not working (disabled, retired or unemployed) or other (student or in unpaid work). Income, initially recorded in bands, was dichotomized at a median split of $70 000 per year. A further variable was created indicating whether or not the participant engaged in health protective behaviours, defined as self-reported screening for either prostate or breast cancer (yes/no).

The distributions of continuous variables were then checked graphically and for skewness, with those not normally distributed being converted to dichotomized categorical variables using a median split. These consisted of: perceived availability of social support, number of social contacts per week and number of social telephone calls per week.

Variables that were not recoded were: age, body mass index, total physical functioning score (SF-36),41 psychological distress (K10),39 number of times engaged in moderate and vigorous physical activity per week, having private health insurance (yes/no), requiring help for a disability (yes/no), being a carer for a sick or disabled person (yes/no), having a self-reported history of heart disease (yes/no), has had treatment for heart disease in the past month (yes/no), has a family history of heart disease (yes/no), ever being diagnosed with depression (yes/no), ever having been treated for depression in the past month (yes/no), ever having been diagnose with anxiety (yes/no), being treated for anxiety in the past month (yes/no), having a family history for depression (yes/no), is a current smoker (yes/no) and self-rated health (with 1 being poor and 5 being excellent). Any variable with >10% of the total data set missing was excluded from further analysis.

The univariate association of each variable with consent status was evaluated using independent sample t-test, Mann–Whitney U-test and χ2 test as appropriate. A multivariable binary logistic regression analysis was then completed using the enter method to assess the ability of these data to predict consent to participate in the research. Variables were included in the regression model on an empirical basis: those that had a statistical difference between the two groups of P=<0.10. Autocorrelations, considered to be a correlation of r>0.30, were assessed before modelling, and variables identified a priori as being more relevant (for example, depression versus anxiety) were entered into the model.

Trial outcome measure and sampling bias

The primary outcome measure of the study was depressive symptoms as assessed by the Primary Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9), a widely used 9-item, self-report tool designed for community samples. Items are scored on a 0–3 scale and are provided with a summary score ranging from 0 to 27. The PHQ-9 has shown to have sufficient sensitivity and specificity for major depressive disorder,42, 43 and an indicator of minimal clinically important change for individuals.44

In order to determine if any factors associated with consent to participation biased outcome, logistic regression models were completed using the data from the 487 participants who met inclusion and exclusion criteria and finally entered the trial and had outcome data available postintervention. The regression used the enter method to determine the association between the variables that were found to be associated with consenting to participate and the outcome—a clinically significant change in depressive symptoms as determined by a reduction in the PHQ score of ≥5. Sequential interactions between treatment arm and each of these variables were then examined.

Ethical approval

Written informed consent was obtained from all the participants and the ethics approval for the 45 and Up Study was provided by the University of New South Wales Human Research Ethics Committee. Ethics approval for the CREDO trial was obtained from the University of Sydney Human Research Ethics Committee.

Results

Factors associated with consent to be assessed for trial inclusion: univariate analyses

Compared with nonconsenters (n=5201), those who consented (n=1885) to be assessed for trial inclusion were significantly more likely to be younger, female, born in Australia and speak English at home (Tables 1 and 2). They were significantly more socioeconomically advantaged on a number of indices, being more likely to have completed some form of education after school and to have private health insurance (which is not compulsory in Australia but encouraged through taxation breaks). They also lived in more socioeconomically advantaged areas as indicated by the SEIFA (Socio-Economics Indexes for Areas) Index of relative socioeconomic advantage, which was derived from the participant’s postcode45 at initial data collection. They were less likely than nonconsenters to be a carer for someone with an illness or disability, and were more commonly engaging in ‘moderate’ physical activity per week. Consenters were also more likely to have been previously diagnosed with depression or anxiety, and to have been treated for either of these in the month before completing the 45 and Up Study baseline survey. There were however, no significant differences between consenters and nonconsenters in any self-reported cardiovascular risk factors: having received treatment for heart attack/angina, other heart disease, hypertension or high blood cholesterol in the past month; taking medications for heart disease, hypertension or high blood cholesterol in the past month; previous doctor’s diagnosis of heart disease, stroke or hypertension; previous doctor’s diagnosis of diabetes and report taking glucose-lowering therapy in the past month; two or more of the following risk factors: current smoker, obese, aged ≥65 years, family history of heart disease or stroke in two or more first-degree relatives.

There were no difference in marital status (married, single or separated) or any other measure of social support, overall physical functioning (SF-36 score), needing assistance for a disability (yes/no) or current level of psychological distress (K10 score).

Results: autocorrelations between significant variables related to consenting to be assessed for trial inclusion

Significant and expected autocorrelations were found between several variables. Where significant correlations were found, the variable that was considered a priori and/or more likely to induce self-selection bias based on the literature was retained for the final analyses. In the final multivariable model, those variables that were retained for further analysis consisted of language spoken at home (over country of birth), having a private health insurance (over having no private health insurance) and having ever been diagnosed with depression (over a family history of depression or anxiety or a personal history of anxiety).

Factors associated with consenting to assessment for trial inclusion: multivariate analysis

A total of 6396 cases were analysed in the final model (Table 3). A significance level of P<0.01 was selected in order to reduce the probability of Type I errors in the statistical analyses because of the large N of the study. Of the 13 variables included in the fully entered model, only 4 made such statistically significant contributions to the final model predicting consent status. These were female sex (odds ratio (OR) 1.11, 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.05–1.19), speaking English at home (OR 1.48, 95% CI 1.15–1.90), having completed further education (OR 1.67, 95% CI 1.46–1.92) and having a prior diagnosis of depression (OR 1.37, 95% CI 1.22–1.55).

The fully entered model accounted for only 3.5% of the variance in consent status. The C-statistic for the model, which is not dependent upon the frequency of the outcome, was only a little greater than chance at 0.6.

A backwards binary logistic regression was modelled using the likelihood ratio method to test the sensitivity of the above model’s results and produced a similar result accounting for 3.7% of the variance in consent status with a C-statistic of 0.598.

Sampling bias with respect to depression outcome among trial completers

A binary logistic regression was completed to determine if the variables found to predict participation influenced the outcome of the trial in the 487 trial participants who had outcome data. None of the four variables included in the model were found to be significantly related to the outcome, a clinically significant improvement in depressive scores, over the trial (Table 4). There was also no interaction of these factors with outcome by treatment arm.

Discussion

Sampling, and specifically a self-selection, bias in the consent to take part in trials may limit the translation of trial results into real-world effects. This is the first study to have been able to evaluate the presence and impact of such a bias. Of the 35 potential sociodemographic, health and behavioural factors assessed, only 4 were independently associated with an increased likelihood of consenting to participate in an internet-delivered randomized controlled trial treating depression in people aged ≥45 years who had high risk of cardiovascular disease: female sex, speaking English, having engaged in further education after school and prior depression diagnosis were consistently associated in all models. The important issue is whether these factors that may influence consent bias the results of the trials by differentially influencing outcome. None of the factors identified in this study did so, either overall or were associated with the proportional effect of the intervention in the active arm.

These four factors identified are partly consistent with previous literature from observational studies that have commonly found that those who are more educated,22, 24 speak English, as opposed to another language in an English-predominant country,46, 47, 48 and are female22, 23, 27 are more likely to participate in research. However, unlike previous research, marital status23, 28, 29 and socioeconomic status27 were not related to consent to participate in this study. Also, contradictory to other findings,20, 21 greater psychological distress at baseline in the health survey did not reduce participation. In fact, a prior diagnosis of depression was associated with a higher likelihood of consenting.

Higher levels of education and speaking English in Australia may lead to individuals doing better in interventional studies because of their socioeconomic advantages,16 through lower rates of attrition from trials49 and/or being more likely to engage in help seeking outside of interventional studies.50 Any undetected effect of this may be that the trial results could overestimate the real-world effect in less educated or minority groups who do not speak English. Women are generally more likely to engage in both help seeking,51, 52, 53, 54 and research studies, as confirmed here. Most55, 56, 57 but not all50 research also tends to indicate that women respond more favourably to treatment for depression in trials. Similarly, in naturalistic studies, women were more likely to achieve better treatment outcomes than men regardless of therapy prescribed.58 Thus, the increased likelihood of women participating in this study may have led to potential overestimation of the benefits that men may receive from the online intervention.

Those consenting to be assessed for trial participation were more likely to have had a prior diagnosis of depression, but did not display a greater level of baseline psychological distress. This may indicate that consenters were more likely either to have a recurrent illness or one with other factors that had warranted prior medical help seeking. Although this may reflect the greater salience of the proposed intervention to this group, recurrent and or more severe episodes have been associated with a poorer outcome.59 However, in our study we found that there was no evidence that the participants with prior depression had poorer outcomes. As shown by Rogge et al.,60 those who think they may be most able to benefit may self-select into the study.

Limitations

A limitation of this study is that it recruited from a population who had already agreed to participate in a longitudinal study of health. As such, they may be more likely to engage in health care, research and/or interventions. The base sample had a high number of unopened, but valid, emails likely to represent less frequent users of the internet, particularly given that a significant number of this group was contactable via postal letter. It is probable that, despite a working email address, these people may be more difficult to engage in an online intervention, potentially needing more technical assistance and frequent reminders to access the programme. This could limit the cost efficiencies of such interventions in the wider population but does not necessarily indicate a bias.

The participation rate (27%) within the CREDO trial appears to be similar, if not better, than that expected from community-recruited internet trials.27, 61, 62 Response rates are likely to be different from trials recruiting directly from clinical centres or intervention waitlists, as community-based studies do not recruit participants actively engaging in help seeking. Therefore, our potential participants may not have previously recognized a need for intervention, or may be less motivated to engage in treatment. Given this, participants who consent to participate may be more motivated or may participate because of interest in research, rather than wanting help per se. However, there was no suggestion that consenters differed on other help-seeking variables such as previous cancer screening. The variables available and their coding were dependent upon the 45 and Up Study baseline data. The use of such categorical variables may have reduced the sensitivity of our analyses and we missed subtle effects. Furthermore, we could not assess potentially more pertinent variables such as psychological attitudes or values about research63, 64 that might have better determined consent status and potentially bias results. It is also important to note that the study population is an older group of individuals who, although self-identified as internet users, are clearly a generation who is not brought up with such technology. Therefore, findings might be limited in their ability to generalize to a younger population.

Finally, this study’s participants had consented to participate in an unguided internet-based intervention for depression. People have different motivations for participating in and persisting with internet interventions65, 66, 67 and the perception of a relationship is often important.66 Given that this was an unguided internet intervention where there was little contact with the research team, those people who believe the relationship to be important may not consent. Therefore, generalizing these results to guided interventions should be done so with caution and further research needs to be completed to determine the difference in consenters and nonconsenters in both guided and unguided interventions.

Future direction

Future research would benefit from prospectively exploring the reasons why people choose to participate in interventional trials and how, and whether, trial participants differ from those accessing open-access interventions. Understanding why people choose to participate in trials might help to increase recruitment and improve the translation of trial results within a health-care model. A difficult, but more fruitful, task will be understanding why nonparticipants did not choose to participate despite experiencing a level of distress. Such research may be best implemented using interviews of people who declined to participate, thereby providing a more in-depth understanding about these barriers and how nonconsenters may differ from those who consent. However, recruitment of this group is likely to be difficult and it may take some time to build up an adequate picture of these barriers to participation.

In summary, although there were some individual factors associated with consent status, the ability of these factors to predict consent was poor, accounting for <3.5% of the variance. Furthermore, and importantly for translating research into real-world outcomes, we were unable to show that any of the self-selection sampling differences between consenters and nonconsenters biased the trial results. This supports the evidence base for the more routine and wider translation of ehealth interventions into effective clinical practice and public health applications.

References

Meyer B, Berger T, Caspar F, Beevers CG, Andersson G, Weiss M . Effectiveness of a novel integrative online treatment for depression (Deprexis): randomized controlled trial. J Med Internet Res 2009; 11: e15.

Webb TL, Joseph J, Yardley L, Michie S . Using the internet to promote health behavior change: a systematic review and meta-analysis of the impact of theoretical basis, use of behavior change techniques, and mode of delivery on efficacy. J Med Internet Res 2010; 12: e4.

Reger MA, Gahm GA . A meta-analysis of the effects of internet- and computer-based cognitive-behavioral treatments for anxiety. J Clin Psychol 2009; 65: 53–75.

Spek V, Cuijpers P, Nyklicek I, Riper H, Keyzer J, Pop V . Internet-based cognitive behaviour therapy for symptoms of depression and anxiety: a meta-analysis. Psychol Med 2007; 37: 319–328.

Cuijpers P, Donker T, Johansson R, Mohr DC, van Straten A, Andersson G . Self-guided psychological treatment for depressive symptoms: a meta-analysis. PLoS One 2011; 6: e21274.

de Graff LE, Gerhards SA, Arntz A, Riper H, Metsemakers JF, Evers SM et al. Clinical effectiveness of online computerised cognitive-behavioural therapy without support for depression in primary care: randomised trial. Br J Psychiatry 2009; 195: 73–80.

Spek V, Cuijpers P, Nyklicek I, Smits N, Riper H, Keyzer J et al. One-year follow-up results of a randomized controlled clinical trial on internet-based cognitive behavioural therapy for subthreshold depression in people over 50 years. Psychol Med 2008; 38: 635–639.

Warmerdam L, van Straten A, Twisk J, Riper H, Cuijpers P . Internet-based treatment for adults with depressive symptoms: randomized controlled trial. J Med Internet Res 2008; 10: e44.

van Straten A, Cuijpers P, Smits N . Effectiveness of a web-based self-help intervention for symptoms of depression, anxiety, and stress: randomized controlled trial. J Med Internet Res 2008; 10: e7.

Christensen H, Griffiths KM, Mackinnon AJ, Brittliffe K . Online randomized controlled trial of brief and full cognitive behaviour therapy for depression. Psychol Med 2006; 36: 1737–1746.

Ryan ML, Shochet IM, Stallman HM . Universal online interventions might engage psychologically distressed university students who are unlikely to seek formal help. Adv Mental Health 2008; 9: 73–83.

National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health.. Depression. The treatment and management of depression in adults. National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE): London (UK), 2009.

National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Common mental health disorders: identification and pathways to care, 2011, [cited 26/09/11]: Available fromhttp://www.nice.org.uk/nicemedia/live/13476/54520/54520.pdf.

Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN). Non-pharmaceutical management of depression in adults. A national clinical guideline. Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN): Edinburgh,Scotland, 2010.

Department of Veteran Affairs. VA/DoD Clinical Practice Guideline for Management of Major Depressive Disorder (MDD). Department of Veteran Affairs, Department of Defense: Washington (DC), 2009.

Wisniewski SR, Rush AJ, Nierenberg AA, Gaynes BN, Warden D, Luther JF et al. Can phase III trial results of antidepressant medications be generalized to clinical practice? A STAR*D report. Am J Psychiatry 2009; 166: 599–607.

van der Lem R, van der Wee NJ, van Veen T, Zitman FG . The generalizability of antidepressant efficacy trials to routine psychiatric out-patient practice. Psychol Med 2011; 41: 1353–1363.

Rothman KJ, Greenland S . Precision and validity in epidemiologic studies. In: Rothman KJ, Greenland S, (eds). Modern Epidemiology. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins: Philadelphia, PA, 1998 pp 115–134.

Eysenbach G, Wyatt J . Using the Internet for surveys and health research. J Med Internet Res 2002; 4: E13.

van Heuvelen MJG, Hochstenbach JBM, Brouwer WH, de Greef MHG, Zijlstra GAR, van Jaarsveld E et al. Differences between participants and non-participants in an RCT on physical activity and psychosocial interventions for older persons. Aging Clin Exp Res 2005; 17: 236–245.

Almeida L, Kashdan TB, Nunes T, Coelho R, Albino-Teixeira A, Soares-da-Silva P . Who volunteers for phase I clinical trials? Influences of anxiety, social anxiety and depressive symptoms on self-selection and the reporting of adverse events. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 2008; 64: 575–582.

Ganguli M, Lytle ME, Reynolds MD, Dodge HH . Random versus volunteer selection for a community-based study. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 1998; 53: M39–M46.

Korkeila K, Suominen S, Ahvenainen J, Ojanlatva A, Rautava P, Helenius H et al. Non-response and related factors in a nation-wide health survey. Eur J Epidemiol 2001; 17: 991–999.

Martinson BC, Crain AL, Sherwood NE, Hayes MG, Pronk NP, O’Connor PJ . Population reach and recruitment bias in a maintenance RCT in physically active older adults. J Phys Act Health 2010; 7: 127–135.

Knudsen AK, Hotopf M, Skogen JC, Overland S, Mykletun A . The health status of nonparticipants in a population-based health study: the Hordaland Health Study. Am J Epidemiol 2010; 172: 1306–1314.

Tolonen H, Laatikainen T, Helakorpi S, Talala K, Martelin T, Prattala R . Marital status, educational level and household income explain part of the excess mortality of survey non-respondents. Eur J Epidemiol 2010; 25: 69–76.

Stopponi MA, Alexander GL, McClure JB, Carroll NM, Divine GW, Calvi JH et al. Recruitment to a randomized web-based nutritional intervention trial: characteristics of participants compared to non-participants. J Med Internet Res 2009; 11: e38.

Goodman A, Gatward R . Who are we missing? Area deprivation and survey participation. Eur J Epidemiol 2008; 23: 379–387.

Harald K, Salomaa V, Jousilahti P, Koskinen S, Vartiainen E . Non-participation and mortality in different socioeconomic groups: the FINRISK population surveys in 1972-92. J Epidemiol Community Health 2007; 61: 449–454.

Rush J, Wisniewski SR, Warden D, Luther JF, Davis LL, Fava M et al. Selecting among second-step antidepressant medication monotherapies: predictive value of clinical demographic, or first-step treatment features. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2008; 65: 870–880.

Van HL, Schoevers RA, Dekker J . Predicting the outcome of antidepressants and psychotherapy for depression: a qualitative, systematic review. Harv Rev Psychiatry 2008; 16: 225–234.

Sotsky SM, Glass DR, Shea MT, Pilkonis PA, Collins JF, Elkin I et al. Patient predictors of response to psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy: findings in the NIMH Treatment of Depression Collaborative Research Program. Am J Psychiatry 1991; 148: 997–1008.

Trivedi MH, Rush AJ, Wisniewski SR, Nierenberg AA, Warden D, Ritz L et al. Evaluation of outcomes with citalopram for depression using measurement-based care in STAR*D: implications for clinical practice. Am J Psychiatry 2006; 163: 28–40.

Drago A, Serretti A . Sociodemographic features predict antidepressant trajectories of response in diverse antidepressant pharmacotreatment environments: a comparison between the STAR*D study and an independent trial. J Clin Psychopharmacol 2011; 31: 345–348.

Cohen A, Houck PR, Szanto K, Dew MA, Gilman SE, Reynolds CF . Social inequalities in response to antidepressant treatment in older adults. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2006; 63: 50–56.

Cockayne NL, Glozier N, Naismith SL, Christensen H, Neal B, Hickie IB . Internet-based treatment for older adults with depression and co-morbid cardiovascular disease: protocol for a randomised, double-blind, placebo controlled trial. BMC Psychiatry 2011; 11: 10.

Banks E, Redman S, Jorm L, Armstrong B, Bauman A, Beard J et al. Cohort profile: the 45 and up study. Int J Epidemiol 2008; 37: 941–947.

Mealing NM, Banks E, Jorm LR, Steel DG, Clements MS, Rogers KD . Investigation of relative risk estimates from studies of the same population with contrasting response rates and designs. BMC Med Res Methodol 2010; 10: 26.

Kessler RC, Andrews G, Colpe LJ, Hiripi E, Mroczek DK, Normand SL et al. Short screening scales to monitor population prevalences and trends in non-specific psychological distress. Psychol Med 2002; 32: 959–976.

Andrews G, Slade T . Interpreting scores on the Kessler Psychological Distress Scale (K10). Aust N Z J Public Health 2001; 25: 494–497.

Ware JE, Kosinski M, Gandek. B . SF-36 Health Survey: Manual & Interpretation Guide. Health Assessment Lab: Boston, Massachusetts, 2000.

Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB . The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med 2001; 16: 606–613.

Gilbody S, Richards D, Brealey S, Hewitt C . Screening for depression in medical settings with the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ): a diagnostic meta-analysis. J Gen Intern Med 2007; 22: 1596–1602.

Lowe B, Unutzer J, Callahan CM, Perkins AJ, Kroenke K . Monitoring depression treatment outcomes with the patient health questionnaire-9. Med Care 2004; 42: 1194–1201.

Australian Bureau of Statistics. SEIFA: Socio-Economic Indexes for Areas 2008 Available fromhttp://www.abs.gov.au/websitedbs/D3310114.nsf/home/Seifa_entry_page.

Hunt S, Bhopal R . Self reports in research with non-English speakers. BMJ 2003 16; 327: 352–353.

Bartlett C, Davey P, Dieppe P, Doyal L, Ebrahim S, Egger M . Women older persons, and ethnic minorities: factors associated with their inclusion in randomised trials of statins 1990 to 2001. Heart. 2003; 89: 327–328.

Sheikh A, Halani L, Bhopal R, Netuveli G, Partridge MR, Car J et al. Facilitating the recruitment of minority ethnic people into research: qualitative case study of South Asians and asthma. PLoS Med 2009; 6: e1000148.

Warden D, Trivedi MH, Wisniewski SR, Davis L, Nierenberg AA, Gaynes BN et al. Predictors of attrition during initial (citalopram) treatment for depression: a STAR*D report. Am J Psychiatry 2007; 164: 1189–1197.

Cotten SR, Gupta SS . Characteristics of online and offline health information seekers and factors that discriminate between them. Soc Sci Med 2004; 59: 1795–1806.

LeongFTLZ P . Gender and opinions about mental illness as predictors of attitudes toward seeking professional psychological help. Br J Guid Counc 1999; 27: 123–132.

Mackenzie CS, Gekoski WL, Knox VJ . Age, gender, and the underutilization of mental health services: the influence of help-seeking attitudes. Aging Ment Health 2006; 10: 574–582.

Steffens DC, Skoog I, Norton MC, Hart AD, Tschanz JT, Plassman BL et al. Prevalence of depression and its treatment in an elderly population: the Cache County study. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2000; 57: 601–607.

Moller-Leimkuhler AM . Barriers to help-seeking by men: a review of sociocultural and clinical literature with particular reference to depression. J Affect Disord 2002; 71: 1–9.

Young EA, Kornstein SG, Marcus SM, Harvey AT, Warden D, Wisniewski SR et al. Sex differences in response to citalopram: a STAR*D report. J Psychiatr Res 2009; 43: 503–511.

Berlanga C, Flores-Ramos M . Different gender response to serotonergic and noradrenergic antidepressants. A comparative study of the efficacy of citalopram and reboxetine. J Affect Disord 2006; 95: 119–123.

Khan A, Brodhead AE, Schwartz KA, Kolts RL, Brown WA . Sex differences in antidepressant response in recent antidepressant clinical trials. J Clin Psychopharmacol 2005; 25: 318–324.

Yang SJ, Kim SY, Stewart R, Kim JM, Shin IS, Jung SW et al. Gender differences in 12-week antidepressant treatment outcomes for a naturalistic secondary care cohort: the CRESCEND study. Psychiatry Res 2011 30; 189: 82–90.

Conradi HJ, de Jonge P, Ormel J . Prediction of the three-year course of recurrent depression in primary care patients: different risk factors for different outcomes. J Affect Disord 2008; 105: 267–271.

Rogge RD, Cobb RJ, Story LB, Johnson MD, Lawrence EE, Rothman AD et al. Recruitment and selection of couples for intervention research: achieving developmental homogeneity at the cost of demographic diversity. J Consult Clin Psychol 2006; 74: 777–784.

Oenema A, Brug J, Dijkstra A, De Weerdt I, De Vries H . Efficacy and use of an internet-delivered computer-tailored lifestyle intervention, targeting saturated fat intake, physical activity and smoking cessation: a randomized controlled trial. Ann Behav Med 2008; 35: 125–135.

Spittaels H, De Bourdeaudhuij I, Brug J, Vandelanotte C . Effectiveness of an online computer-tailored physical activity intervention in a real-life setting. Health Educ Res 2007; 22: 385–396.

Willis KF, Robinson A, Wood-Baker R, Turner P, Walters EH . Participating in research: exploring participation and engagement in a study of self-management for people with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Qual Health Res 2011; 21: 1273–1282.

Fearn P, Avenell A, McCann S, Milne AC, Maclennan G . Factors influencing the participation of older people in clinical trials - data analysis from the MAVIS trial. J Nutr Health Aging 2010; 14: 51–56.

Bendelin N, Hesser H, Dahl J, Carlbring P, Nelson KZ, Andersson G . Experiences of guided Internet-based cognitive-behavioural treatment for depression: a qualitative study. BMC Psychiatry 2011; 11: 107.

Donkin L, Glozier N . Motivators and motivations to persist with online psychological interventions: a qualitative study of treatment completers. J Med Internet Res 2012; 14: e91.

Gerhards SA, Abma TA, Arntz A, de Graaf LE, Evers SM, Huibers MJ et al. Improving adherence and effectiveness of computerised cognitive behavioural therapy without support for depression: a qualitative study on patient experiences. J Affect Disord 2011; 129: 117–125.

Acknowledgements

This CREDO research trial is supported by the Cardiovascular Disease and Depression Strategic Research Program (Award Reference No. G08S 4048) funded by the National Heart Foundation of Australia and beyondblue: the national depression initiative. The 45 and Up Study is managed by The Sax Institute in collaboration with major partner, Cancer Council New South Wales, and partners the National Heart Foundation of Australia (NSW Division); NSW Health; beyondblue: the national depression initiative; Ageing, Disability and Home Care, Department of Human Services NSW; and UnitingCare Ageing.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

HC was a co-developer of the free ehealth intervention e-couch (www.ecouch.anu.edu.au/). The other authors declare no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 Unported License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Donkin, L., Hickie, I., Christensen, H. et al. Sampling bias in an internet treatment trial for depression. Transl Psychiatry 2, e174 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1038/tp.2012.100

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/tp.2012.100

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Reasons for dropping out of internet-based problem gambling treatment, and the process of recovery – a qualitative assessment

Current Psychology (2023)

-

A randomized controlled trial on a self-guided Internet-based intervention for gambling problems

Scientific Reports (2021)

-

Internet-based treatment for Romanian adults with panic disorder: protocol of a randomized controlled trial comparing a Skype-guided with an unguided self-help intervention (the PAXPD study)

BMC Psychiatry (2016)

-

A randomised control trial of an Internet-based cognitive behaviour treatment for mood disorder in adults with chronic spinal cord injury

Spinal Cord (2016)

-

The EVIDENT-trial: protocol and rationale of a multicenter randomized controlled trial testing the effectiveness of an online-based psychological intervention

BMC Psychiatry (2013)