Abstract

Dynamic global vegetation models (DGVM) exhibit high uncertainty about how climate change, elevated atmospheric CO2 (atm. CO2) concentration, and atmospheric pollutants will impact carbon sequestration in forested ecosystems. Although the individual roles of these environmental factors on tree growth are understood, analyses examining their simultaneous effects are lacking. We used tree-ring isotopic data and structural equation modeling to examine the concurrent and interacting effects of water availability, atm. CO2 concentration, and SO4 and nitrogen deposition on two broadleaf tree species in a temperate mesic forest in the northeastern US. Water availability was the strongest driver of gas exchange and tree growth. Wetter conditions since the 1980s have enhanced stomatal conductance, photosynthetic assimilation rates and, to a lesser extent, tree radial growth. Increased water availability seemingly overrides responses to reduced acid deposition, CO2 fertilization, and nitrogen deposition. Our results indicate that water availability as a driver of ecosystem productivity in mesic temperate forests is not adequately represented in DGVMs, while CO2 fertilization is likely overrepresented. This study emphasizes the importance to simultaneously consider interacting climatic and biogeochemical drivers when assessing forest responses to global environmental changes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Long-term changes in tree growth and forest productivity have been attributed to multiple climatic and biogeochemical drivers including regional changes in temperature and precipitation regimes, elevated atm. CO2 concentration, nitrogen deposition, and atmospheric pollution1,2. Still, a critical question remains “What are the simultaneous impacts of divergent and interacting environmental drivers of forest productivity?” Although moderate warming, higher atm. CO2 concentration, and nitrogen deposition can enhance forest productivity and carbon sequestration3,4, increased heat5, drought6, and atmospheric pollution2 could counteract these positive effects. Disentangling the impact of these drivers on forest productivity is crucial for better anticipating future changes in biogeochemical cycles and ecosystem services.

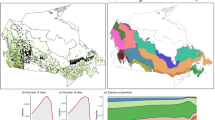

One region where the simultaneous influence of multiple environmental drivers on forest productivity can be tested is the northeastern United States (US). Over the last decades, this region has experienced simultaneous and significant shifts in moisture availability7, increases in atm. CO2 concentration, and reductions in acid and nitrogen deposition4,8 (Fig. 1). While there has been a substantial reduction in acid deposition in northeastern US, there is still not a consensus that reduced pollutant loads have enhanced tree growth in temperate mesic forests9,10,11. The simultaneous increase in water availability and decrease in acid deposition complicate our understanding of the potential benefits of reduced acid deposition. At the same time, the divergent influences between moisture stress and potential CO2 fertilization have led to significant disagreement between remotely sensed (satellite) and modeled (DGVM) productivity of temperate mesic forests12. Investigating the concurrent effects of varying environmental drivers on growth and gas exchange of trees is critical to improve DGVM and better understand the rates, magnitude, and trajectory of terrestrial carbon budgets.

(a) Location of Black Rock Forest and distribution range of Liriodendron tulipifera L. and Quercus rubra L. in North America. Data source: https://gec.cr.usgs.gov/data/little/. (b) Total SO4 and inorganic N wet deposition per hectare for the water year (previous October to current September) at Black Rock Forest, NY. Deposition data were obtained from the National Acid Deposition Program (http://nadp.sws.uiuc.edu); 1981 to 1983 data are from Station NY51, located 6 km from Black Rock Forest, while 1984–2014 data are from Station NY99, located at Black Rock Forest. (c) Standardized climatic water balance during the summer (June–August) calculated as the difference between precipitation and potential evapotranspiration. Positive values in blue indicate wet conditions and negative values in red show dry conditions. Estimated atmospheric CO2 concentrations from ice core data for the period 1895–1958 (dashed black line) and measured data from 1958 to 2014 (black line), CO2 data source: http://www.columbia.edu/~mhs119/GHGs/CO2.1850-2015.txt. Figure created with R version 3.2.261.

Trees acclimate to environmental changes at the leaf level by adjusting their stomatal conductance (gs) and photosynthetic assimilation rates (A). These adjustments translate into changes in allocation and growth13,14. Concurrent adjustments at the tree level interact and influence transpiration and carbon assimilation rates from stand to landscape scales15. Long-term information on physiological and environmental processes at annual and seasonal time-scales can be gained through stable isotopic analysis of tree rings16,17. Stable isotopic analysis can be used to assess how stomatal conductance and photosynthesis respond to shifts in moisture availability18, increasing CO2 concentration19, and reductions in acid deposition20.

Here, we assess the simultaneous effects of changes in key environmental factors on gas exchange and tree growth in a temperate mesic forest of northeastern US using isotopic records from tree rings of two dominant and widely distributed tree species in eastern North America, Liriodendron tulipifera L. and Quercus rubra L. (see Methods, Fig. 1, Supplementary Table S1). Under dry conditions, L. tulipifera has an isohydric behavior and constrains its stomatal conductance so that mid-day water potential minima is kept below a critical threshold21. In contrast, Q. rubra shows an anisohydric behavior and maintains constant levels of stomatal conductance during drought at the risk of incurring xylem cavitation21. Contrasting physiological behavior and habitats of our study trees make them ideal for isolating growth and physiological responses to concurrent but divergent changes in key environmental factors. We first assess the simultaneous influences of changes in atmospheric CO2 concentration, climatic water balance, and SO4 and N deposition on tree growth and physiological mechanisms with structural equation models (SEM, Fig. 2). Second, we analyze the growth, carbon isotope discrimination (Δ13C), intrinsic water-use efficiency (iWUE), and oxygen isotopic ratio (δ18O) responses of trees to shifting moisture conditions, from the extreme 1960s drought to repeated pluvial periods since the 1980s (Fig. 1c).

Results and Discussion

Hypothetically, broadleaf trees in temperate mesic forests are sensitive to moisture availability because of poor stomatal regulation, low hydraulic conductance, high leaf area, and the high radiation and evaporative demands experienced by their large crowns22. We found support for this hypothesis through the high sensitivity of mature (>100 yrs old) L. tulipifera and Q. rubra to moisture availability irrespective of their physiological behavior (isohydric vs anisohydric) and site conditions (moist lowland vs shallow-soiled ridge site). Particularly, we observed a strong coupling between moisture availability and gas exchange of trees as indicated by the strong correlations between the isotopic tree-ring data and summer climatic water balance (Δ13C, r = 0.73 and 0.65; δ18O, r = −0.71 and −0.55) and maximum vapor pressure deficit (Δ13C, r = −0.70 and −0.70; δ18O, r = 0.71 and 0.56) (Table 1). Such high correlations indicate an even greater sensitivity of temperate broadleaf trees to drought than a recent analysis over the eastern US23. Given that our period of study covers one of the wettest periods of the last 500 years7, if not the last 3000–5000 years24, the strong sensitivity of tree gas exchange and to a lower degree of growth to moisture availability in this mesic region is particularly striking.

Elevated atm. CO2 concentration has been found to stimulate tree growth by indirectly enhancing photosynthetic rates and iWUE25,26. When simultaneously analyzing tree sensitivity to summer climatic water balance, atm. CO2 concentration, and SO4 and N deposition, however, we found that water availability was the most important factor. Climatic water balance during the summer (June, July, August) was the strongest driver of BAI, Δ13C, iWUE, and δ18O in both species (Fig. 3). In contrast, atm. CO2 concentration, SO4, and N deposition, which showed significant covariation, exhibited negligible effects. Even if elevated atm. CO2 concentration directly improved iWUE (although this is partly due to the inclusion of CO2 in iWUE calculation, Supplementary Methods S1, eqn. 3), the inexistent or negative associations found between iWUE and BAI, as well as between atm. CO2 concentration and BAI indicate little to no stimulation of growth to CO2. These findings match experiments in mature forests where elevated atm. CO2 concentration and increases in iWUE do not necessarily translate into enhanced radial tree growth27. In those settings, heat and drought stress16,28,29 or limited nutrient availability30 override CO2 effect. The lack of evidence of CO2 fertilization effect on tree growth in our study cannot be attributed to moisture deficit or warming-induced drought stress because the period of the SEM analysis (1981–2014) is the wettest period of the instrumental period that began in 1895. Therefore, our results indicate that CO2-induced growth enhancement25 is unlikely for mature trees under natural conditions when the effects of the concomitant and significant covariation in climatic water balance, SO4 deposition, and N deposition are considered.

Fitted piecewise structural equation models showing the relative influence of the summer climatic water balance, atmospheric CO2 concentration, and SO4 and N wet deposition on tree growth inferred from basal area increment (BAI), Δ13C (a,b), iWUE (c,d), and δ18O. Period of analysis 1981–2014. The random tree identity effect (5 trees per species) was considered by fitting each response variable to a linear mixed effects model within the structural equation models. Single-headed arrows indicate causal relationships and double-headed arrows denote covariation between variables. The width of arrows is proportional to the strength of path coefficients. Numbers next to the paths indicate standardized path coefficients. Coefficients with ns are not significant, but improved the model fit. Solid and dashed paths indicate positive and negative effects, respectively. Grey paths indicate covariation between explanatory variables. Amount of variance explained by the model (R2) is listed for each response variable. The chi-square (Χ2) p-value, degree of freedom (df), and number of observations (n) are shown in the lower left.

Acid deposition can alter leaf physiology and stomatal conductance, indirectly modify isotope ratios in tree rings20, and influence tree growth9. When we simultaneously analyzed the effects of the climatic water balance, atm. CO2 concentration, and atmospheric deposition on trees, we did not detect any direct effect of SO4 and N deposition on BAI and only found some direct but small effects of SO4 and N deposition on Δ13C, iWUE, and δ18O (Fig. 3). However, these direct effects on tree-ring isotopic ratios were not translated into changes in growth. Inexistent or negative correlations were found between Δ13C or iWUE and BAI. L. tulipifera, a species with arbuscular mycorrhizal association, may show higher growth to increased availability of inorganic N from atmospheric deposition4,31. However, the SEM indicated no direct positive association between N deposition and BAI of L. tulipifera. Similarly, the BAI of Q. rubra did not show any direct association with SO4 and N deposition despite the presence of some minor correlations between tree-ring Δ13C and δ18O with N and SO4, respectively. These results do not support previous findings that showed a high sensitivity of this species to S and N deposition32 and N-induced growth enhancement under natural conditions4,33. The absence of growth response to N deposition found for both species agrees with the results of an N-addition experiment done in the Catskill Mountains of southeastern New York State where N addition had no significant effects on aboveground biomass production34.

Our SEM analysis indicates that moisture is the primary driver of gas exchange and growth for both species, even during an anomalously wet period. From these analyses, the increase in forest growth recently observed in the northeastern US4,9,35 is likely less related to rising atm. CO2 concentration and changes in acid/nitrogen deposition and more likely driven by regional wetting7,35. Supporting this inference, change-point detection analysis of the climatic water balance time-series identified a tipping point in moisture availability with drier conditions prior to 1983 and wetter after (Fig. 4a,b). Concurrent to this water availability increase, L. tulipifera and Q. rubra exhibited a simultaneous shift in BAI, Δ13C, iWUE, and δ18O (Fig. 4) indicating a strong coupling between growth, gas exchange, and moisture conditions. A similar increase in tree-ring Δ13C and enhancement in growth was found in the Q. rubra Harvard Forest eddy-flux tower forest following the regional increased in water availability35.

Climatic water balance (a,b), basal area increment (c,d), Δ13C (e,f), iWUE (g,h), and δ18O (i,j) of Liriodendron tulipifera and Quercus rubra for the dry 1950–1983 (light orange fill) and wet 1984–2014 (light blue fill) period. The dry and wet period were identified in the climatic water balance time series applying change-point detection test. Significance levels of the slopes from Mann-Kendall trend tests and Theil-Sen trend estimates: *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001. P-values from the Kolmogorov–Smirnov tests between the dry and wet period are shown. Variables were standardized (z-score) before.

While BAI, Δ13C, and iWUE mainly increased as the climate became wetter, tree-ring δ18O started to decrease (Fig. 4) because of changes in isotopic composition of water sources and stomatal response to lower evaporative demand of the atmosphere. Variation in tree-ring δ18O is primarily due to evaporative enrichment at the leaf level, biochemical fractionation during oxygen incorporation, and isotopic signature of tree source water, which is mainly influenced by the δ18O of precipitation and soil evaporative enrichment36,37. The δ18O value of precipitation is essentially influenced by air temperature, precipitation amount, moisture sources, air mass trajectory, and seasonality38.

In our study region, the δ18O of precipitation has changed through time (Supplementary Methods S2, Fig. S1). Between 1968 and 2010, a significant reduction in δ18O of precipitation (−0.089‰ yr−1) was recorded in northeastern US due in large part to the increase in the proportion of Arctic precipitation sources which are more depleted in δ18O ratios38. This decrease in δ18O of precipitation may have potentially influenced the isotopic signature of the source water of our trees and caused a gradual reduction in tree-ring δ18O values through time (Fig. 4i). However, the strong coupling between tree-ring δ18O and moisture availability (Table 1) indicates that the decrease in tree-ring δ18O was also due to a reduction in transpiration at the leaf level in response to the lower evaporative demand of the atmosphere as the climate became wetter.

Synchronically to the decrease in δ18O tree-ring values, rising Δ13C and BAI (Fig. 4e,c) suggest that C-assimilation and stomatal conductance also increased. Taken together, the concurrent depletion of δ18O and increase in Δ13C indicate that, despite the reduction in δ18O of precipitation over the study region, changes in transpiration, stomatal conductance, and photosynthetic assimilation rates occurred simultaneously and tracked the abrupt shift in climatic water balance that began in the early 1980s. The long-term trends recorded in our tree-ring δ18O time series, however, should be interpret with caution as changes in the isotopic signature of source water in time and the reduction in evaporative enrichment at the leaf level driven by the increase in water availability have likely occurred at the same time.

Overall, we found that moisture is the main driver of increased gas exchange and, to a lesser degree, increased radial growth of two broadleaf trees in a mesic temperate forest in the northeastern US during the period of opposing trajectories of acid and N deposition, atm. CO2 concentration, and water availability. Simultaneous analysis of these drivers on tree-ring isotopic composition and growth indicates that the reported growth recovery from reduced acid deposition9 and N-induced growth enhancement in northeastern US forests33 might be the result of a possible omission of the concurrent shift in water availability and atm. CO2 concentration. Additionally, results here do not find support for atm. CO2 fertilization on broadleaf tree growth in mature temperate mesic forests of northeastern US25, a region where greening trends have been mainly attributed to increased atm. CO2 concentration and land cover change1. Our work emphasizes the need to simultaneously consider changes in water availability, atm. CO2 concentration, and acid/nitrogen deposition at large spatial scales to gain a more complete understanding of future changes in forest productivity.

As the climate is getting warmer and wetter in northeastern US (Supplementary Fig. S2), our observed sensitivity of broadleaf trees to moisture availability is important. The expected increases in severity, frequency and duration of drought periods would likely have a significant impact on tree growth, mortality rates, and forest composition39. Although the temperate mesic forests of the northeastern US have not experienced severe and long-lasting drought since the 1960s7, the strong and persistent response of trees to water availability reported here as well as in recent studies35,39 reveals a vulnerability of mesic forests to drought.

Methods

Study sites and dendrochronological analysis

We conducted this study at Black Rock Forest (41°24′N, 74°01′W), a 1550 ha forest preserve in southeastern New York State40. We sampled L. tulipifera in a lowland site located on a south-facing slope at 170 m a.s.l. on loamy soils and Q. rubra at the ridge of an upper slope site at 400 m a.s.l., situated 2 km away from the lowland site, and characterized by shallow soils with abundant rock outcrops. We extracted two 5 mm diameter increment cores from 15 dominant and healthy L. tulipifera and Q. rubra trees for tree-ring width measurements (Supplementary Table S1). The increment cores were air dried, glued on wood mounts, and successively sanded with finer grades of sandpaper until the xylem structure and ring boundaries were clearly visible. We measured ring widths to the nearest 0.001 mm. Individual tree-ring width series were crossdated and statistically checked with the program COFECHA41. To ensure that the number of trees sampled was sufficient and representative of the sampled population, we calculated the express population signal (EPS). All tree-ring chronologies showed EPS values ≥ 0.85, which is considered the threshold value for adequately reflecting a common signal among trees (Supplementary Table S1)42. To detect long-term changes in growth, we converted the individual raw tree-ring width series to basal area increments (BAI) and removed the potential age related trends that can bias long-term growth changes with a Regional Curve Standardization (RCS) approach (Supplementary Fig. S3)43. We calculated an average ontogenetic growth curve for each species (i.e., the regional curve) by aligning the raw BAI measurements of each tree to the biological age of the rings. We then divided each raw individual BAI series by this average curve to produce RCS residual BAI series44,45. RCS residual BAI series were used in further analyses.

Isotopic analysis

Tree-ring δ13C was used to calculate carbon isotope discrimination (Δ13C, Supplementary Methods S1). Δ13C in tree rings provides an integrated record between intercellular and atm. CO2 concentration during the period when the carbon was fixed by the enzyme Ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase (RuBisCO) in chloroplasts46. With further calculations, iWUE, i.e., the ratio between A and gs, can be determined from Δ13C (Supplementary Methods S1)47. By contrast, the oxygen isotopic ratios in tree rings integrate the isotopic composition of source water and the stomatal response to changes in vapor pressure deficit36,37. Thus, the δ18O ratio contains an indirect record of gs and can help understanding the influence of A and gs on Δ13C and iWUE18. Therefore, by examining concurrent variations in both Δ13C and δ18O, insights can be gained on how stomatal conductance and photosynthesis respond to shifts in climatic water balance, increasing atm. CO2 concentration, and reductions in acid deposition.

For the isotopic analysis, we selected the five trees per species with the highest correlations with the tree-ring width master chronology and took an extra 12 mm diameter core per tree. We analyzed the isotopic ratios in each tree and each annual ring individually for the period 1950–2014. From each core, we split off the latewood of each annual ring with a scalpel under a stereomicroscope, chopped the material, and stored each latewood sample individually in centrifugal tubes before cellulose extraction. We extracted the α-cellulose following standard procedures48,49 and homogenized the cellulose using an ultrasound treatment50. For each sample, 200 μg of cellulose were weighted and put in silver capsules. δ13C and δ18O were measured simultaneously using high-temperature pyrolysis in a Costech elemental analyzer interfaced with an Elementar Isoprime mass spectrometer at the Department of Geology at the University of Maryland, USA51. The analytical precision for the in-house α-cellulose standards was ±0.17‰ for δ13C and ±0.34‰ for δ18O.

Climate and atmospheric deposition data

Modeled mean monthly minimum and maximum temperature, total monthly precipitation and maximum vapor pressure deficit for the period 1895–2014 were obtained from the PRISM Climate Group, Oregon State University (http://prism.oregonstate.edu). We used the mean monthly minimum and maximum temperature and total precipitation to compute a monthly climatic water balance, i.e., precipitation minus potential evapotranspiration. Evapotranspiration was calculated according to Hargreaves52.

To assess the potential effect of atm. CO2 concentration and pollutants on tree growth and physiology, we used historical SO4 and total inorganic N wet deposition data (kg/ha) for the water year (previous October to current September) from two measuring stations from the National Acid Deposition Program (Fig. 1, http://nadp.sws.uiuc.edu), and annual global average CO2 mixing ratio values available online (http://www.columbia.edu/~mhs119/GHGs/CO2.1850-2015.txt).

Data analysis

We first explored the relationships of tree-ring chronologies (BAI, Δ13C, δ18O) with monthly climate variables with bootstrapped correlation functions using the R package treeclim53. We identified the months (i.e., June, July, and August) that have the strongest and significant influence on tree-ring chronologies (Supplementary Figs S4, S5) and further averaged the climate variables over these months and calculated correlation coefficients between summer climate and tree-ring variables (Table 1). Tree-ring and climate time series were prewhitened (removal of the first order autocorrelations) before correlation analysis. The summer climatic water balance was used in further analyses since it showed the strongest correlations with the tree-ring variables.

We performed piecewise structural equation modeling (SEM) using the R package piecewise SEM54 to account for concomitant changes in atm. CO2 concentration, SO4 and N deposition, and climatic water balance, which may be masking the influence of a single environmental variable on the growth and gas exchange of trees (Fig. 2). Piecewise SEMs use advanced multivariate statistical techniques better suited for small sample sizes and allow the simultaneous implementation of non-normal distributions, random effects, and different correlation structures within a traditional SEM framework54,55,56. We developed piecewise SEMs for each species to address the joint effects of changing climatic water balance, atm. CO2 concentration, and SO4 and N deposition on BAI, Δ13C and δ18O of trees. We considered the random tree identity effect (individual tree series) by fitting each response variable to a linear mixed effects model57 using the function lme from the NLME package58. The SEMs were fit for the period 1981–2014, i.e. the time window with available deposition data, and raw tree-ring and environmental data to account for effects of the trends in environmental variables. We assessed the models fits using chi-square p-value and Akaike’s information criterion corrected for small sample size54.

We used the change-point detection test of Pettitt59 to test the shift in the central tendency of the climatic water balance time series. Based on this test, we identified two significant periods with contrasting climatic water balance, i.e., the dry period 1950–1983 and the wet period 1984–2014. We assessed the significance of the changes in BAI, Δ13C, iWUE and δ18O in the dry vs. wet period with probability density functions and Kolmogorov–Smirnov tests. We estimated the temporal trends of the climatic water balance, BAI, Δ13C, iWUE and δ18O time series, and their significance with Mann-Kendall trend tests and Theil-Sen trend estimates60. All data analyses were conducted in R version 3.2.261.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Levesque, M. et al. Water availability drives gas exchange and growth of trees in northeastern US, not elevated CO2 and reduced acid deposition. Sci. Rep. 7, 46158; doi: 10.1038/srep46158 (2017).

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

Zhu, Z. et al. Greening of the Earth and its drivers. Nature Clim. Change 6, 791–795, doi: 10.1038/nclimate3004 (2016).

Ollinger, S. V., Aber, J. D., Reich, P. B. & Freuder, R. J. Interactive effects of nitrogen deposition, tropospheric ozone, elevated CO2 and land use history on the carbon dynamics of northern hardwood forests. Glob. Change Biol. 8, 545–562, doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2486.2002.00482.x (2002).

Keenan, T. F. et al. Net carbon uptake has increased through warming-induced changes in temperate forest phenology. Nature Clim. Change 4, 598–604, doi: 10.1038/nclimate2253 (2014).

Thomas, R. Q., Canham, C. D., Weathers, K. C. & Goodale, C. L. Increased tree carbon storage in response to nitrogen deposition in the US. Nature Geosci. 3, 13–17, doi: 10.1038/ngeo721 (2010).

Ciais, P. et al. Europe-wide reduction in primary productivity caused by the heat and drought in 2003. Nature 437, 529–533, doi: 10.1038/nature03972 (2005).

Allen, C. D., Breshears, D. D. & McDowell, N. G. On underestimation of global vulnerability to tree mortality and forest die-off from hotter drought in the Anthropocene. Ecosphere 6, art129, doi: 10.1890/ES15-00203.1 (2015).

Pederson, N. et al. Is an epic pluvial masking the water insecurity of the greater New York City region? J. Climate 26, 1339–1354, doi: 10.1175/jcli-d-11-00723.1 (2013).

Lawrence, G. B. et al. Declining acidic deposition begins reversal of forest-soil acidification in the northeastern U.S. and eastern Canada. Environ. Sci. Technol. 49, 13103–13111, doi: 10.1021/acs.est.5b02904 (2015).

Thomas, R. B., Spal, S. E., Smith, K. R. & Nippert, J. B. Evidence of recovery of Juniperus virginiana trees from sulfur pollution after the Clean Air Act. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 110, 15319–15324, doi: 10.1073/pnas.1308115110 (2013).

Schaberg, P. G., Hawley, G. J., Rayback, S. A., Halman, J. M. & Kosiba, A. M. Inconclusive evidence of Juniperus virginiana recovery following sulfur pollution reductions. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 111, E1, doi: 10.1073/pnas.1320526111 (2014).

Bishop, D. A. et al. Regional growth decline of sugar maple (Acer saccharum) and its potential causes. Ecosphere 6, 1–14, doi: 10.1890/ES15-00260.1 (2015).

Smith, W. K. et al. Large divergence of satellite and Earth system model estimates of global terrestrial CO2 fertilization. Nature Clim. Change 6, 306–310, doi: 10.1038/nclimate2879 (2016).

Bréda, N., Huc, R., Granier, A. & Dreyer, E. Temperate forest trees and stands under severe drought: a review of ecophysiological responses, adaptation processes and long-term consequences. Annals of Forest Science 63, 625–644, doi: 10.1051/forest:2006042 (2006).

Hartmann, H. & Trumbore, S. Understanding the roles of nonstructural carbohydrates in forest trees – from what we can measure to what we want to know. New Phytol 211, 386–403, doi: 10.1111/nph.13955 (2016).

Frank, D. C. et al. Water-use efficiency and transpiration across European forests during the Anthropocene. Nature Clim. Change 5, 579–583, doi: 10.1038/nclimate2614 (2015).

Lévesque, M., Siegwolf, R., Saurer, M., Eilmann, B. & Rigling, A. Increased water-use efficiency does not lead to enhanced tree growth under xeric and mesic conditions. New Phytol 203, 94–109, doi: 10.1111/nph.12772 (2014).

McCarroll, D. & Loader, N. J. Stable isotopes in tree rings. Quat. Sci. Rev. 23, 771–801, doi: 10.1016/j.quascirev.2003.06.017 (2004).

Scheidegger, Y., Saurer, M., Bahn, M. & Siegwolf, R. T. W. Linking stable oxygen and carbon isotopes with stomatal conductance and photosynthetic capacity: a conceptual model. Oecologia 125, 350–357 (2000).

Waterhouse, J. S. et al. Northern European trees show a progressively diminishing response to increasing atmospheric carbon dioxide concentrations. Quat. Sci. Rev. 23, 803–810 (2004).

Savard, M. M. Tree-ring stable isotopes and historical perspectives on pollution – An overview. Environ. Pollut. 158, 2007–2013, doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2009.11.031 (2010).

Meinzer, F. C. et al. Above- and belowground controls on water use by trees of different wood types in an eastern US deciduous forest. Tree Physiol 33, 345–356, doi: 10.1093/treephys/tpt012 (2013).

McDowell, N. G. & Allen, C. D. Darcy’s law predicts widespread forest mortality under climate warming. Nature Clim. Change 5, 669–672, doi: 10.1038/nclimate2641 (2015).

Martin-Benito, D. & Pederson, N. Convergence in drought stress, but divergence in heat stress across a latitudinal gradient in a temperate broadleaf forest. J. Biogeogr. 42, 925–937, doi: 10.1111/jbi.12462 (2015).

Shuman, B. N. & Marsicek, J. The structure of Holocene climate change in mid-latitude North America. Quat. Sci. Rev. 141, 38–51, doi: 10.1016/j.quascirev.2016.03.009 (2016).

Keenan, T. F. et al. Increase in forest water-use efficiency as atmospheric carbon dioxide concentrations rise. Nature 499, 324–327, doi: 10.1038/nature12291 (2013).

Voelker, S. L. et al. A dynamic leaf gas-exchange strategy is conserved in woody plants under changing ambient CO2: evidence from carbon isotope discrimination in paleo and CO2 enrichment studies. Glob. Change Biol. 22, 889–902, doi: 10.1111/gcb.13102 (2016).

Bader, M. K. F. et al. Central European hardwood trees in a high-CO2 future: synthesis of an 8-year forest canopy CO2 enrichment project. Journal of Ecology 101, 1509–1519, doi: 10.1111/1365-2745.12149 (2013).

Peñuelas, J., Canadell, J. G. & Ogaya, R. Increased water-use efficiency during the 20th century did not translate into enhanced tree growth. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 20, 597–608, doi: 10.1111/j.1466-8238.2010.00608.x (2011).

Andreu-Hayles, L. et al. Long tree-ring chronologies reveal 20th century increases in water-use efficiency but no enhancement of tree growth at five Iberian pine forests. Glob. Change Biol. 17, 2095–2112, doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2486.2010.02373.x (2011).

Norby, R. J. & Zak, D. R. Ecological lessons from free-air CO2 enrichment (FACE) experiments. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst. 42, 181–203, doi: 10.1146/annurev-ecolsys-102209-144647 (2011).

Terrer, C., Vicca, S., Hungate, B. A., Phillips, R. P. & Prentice, I. C. Mycorrhizal association as a primary control of the CO2 fertilization effect. Science 353, 72–74, doi: 10.1126/science.aaf4610 (2016).

Bukata, A. R. & Kyser, T. K. Carbon and nitrogen isotope variations in tree-rings as records of perturbations in regional carbon and nitrogen cycles. Environ. Sci. Technol. 41, 1331–1338, doi: 10.1021/es061414g (2007).

Jennings, K. A., Guerrieri, R., Vadeboncoeur, M. A. & Asbjornsen, H. Response of Quercus velutina growth and water use efficiency to climate variability and nitrogen fertilization in a temperate deciduous forest in the northeastern USA. Tree Physiol 36, 428–443, doi: 10.1093/treephys/tpw003 (2016).

Lovett, G. M., Arthur, M. A., Weathers, K. C., Fitzhugh, R. D. & Templer, P. H. Nitrogen addition increases carbon storage in soils, but not in trees, in an eastern U.S. deciduous forest. Ecosystems 16, 980–1001, doi: 10.1007/s10021-013-9662-3 (2013).

Belmecheri, S. et al. Tree-ring δ13C tracks flux tower ecosystem productivity estimates in a NE temperate forest. Environmental Research Letters 9, 074011, 10.1088/1748-9326/9/7/074011 (2014).

Barbour, M. M. Stable oxygen isotope composition of plant tissue: a review. Functional Plant Biology 34, 83–94, doi: 10.1071/fp06228 (2007).

Roden, J. S., Lin, G. & Ehleringer, J. R. A mechanistic model for interpretation of hydrogen and oxygen isotope ratios in tree-ring cellulose. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta 64, 21–35 (2000).

Puntsag, T. et al. Arctic Vortex changes alter the sources and isotopic values of precipitation in northeastern US. Scientific Reports 6, 22647, doi: 10.1038/srep22647 (2016).

Clark, J. S. et al. The impacts of increasing drought on forest dynamics, structure, and biodiversity in the United States. Glob. Change Biol., doi: 10.1111/gcb.13160 (2016).

Schuster, W. S. F. et al. Changes in composition, structure and aboveground biomass over seventy-six years (1930–2006) in the Black Rock Forest, Hudson Highlands, southeastern New York State. Tree Physiol 28, 537–549, doi: 10.1093/treephys/28.4.537 (2008).

Holmes, R. L. Computer-assisted quality control in tree-ring dating and measurement. Tree-Ring Bull. 43, 69–78 (1983).

Wigley, T. M. L., Briffa, K. R. & Jones, P. D. On the average value of correlated time series, with applications in dendroclimatology and hydrometeorology. Journal of Climate and Applied Meteorology 23, 201–213 (1984).

Peters, R. L., Groenendijk, P., Vlam, M. & Zuidema, P. A. Detecting long-term growth trends using tree rings: a critical evaluation of methods. Glob. Change Biol. 21, 2040–2054, doi: 10.1111/gcb.12826 (2015).

Cook, E. R. & Briffa, K. R. In Methods of Dendrochronology. Applications in the Environmental Sciences(eds Cook, E. R. & Kairiukstis, L. A. ) 97–162 (Kluwer Academic Publishers, 1990).

Briffa, K. R. et al. Fennoscandian summers from ad 500: temperature changes on short and long timescales. Clim. Dynam. 7, 111–119, doi: 10.1007/bf00211153 (1992).

Farquhar, G. D., O’leary, M. & Berry, J. On the relationship between carbon isotope discrimination and the intercellular carbon dioxide concentration in leaves. Aust. J. Plant Physiol. 9, 121–137 (1982).

Farquhar, G. & Richards, R. Isotopic composition of plant carbon correlates with water-use efficiency of wheat genotypes. Aust. J. Plant Physiol. 11, 539–552 (1984).

Loader, N. J., Robertson, I., Barker, A. C., Switsur, V. R. & Waterhouse, J. S. An improved technique for the batch processing of small wholewood samples to α-cellulose. Chem. Geol. 136, 313–317, http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0009-2541(96)00133-7 (1997).

Loader, N. J., Robertson, I. & McCarroll, D. Comparison of stable carbon isotope ratios in the whole wood, cellulose and lignin of oak tree-rings. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 196, 395–407 (2003).

Laumer, W. et al. A novel approach for the homogenization of cellulose to use micro-amounts for stable isotope analyses. Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom. 23, 1934–1940, doi: 10.1002/rcm.4105 (2009).

Evans, M. N., Selmer, K. J., Breeden, B. T., Lopatka, A. S. & Plummer, R. E. Correction algorithm for online continuous flow δ13C and δ18O carbonate and cellulose stable isotope analyses. Geochemistry, Geophysics, Geosystems 17, 3580–3588, doi: 10.1002/2016GC006469 (2016).

Hargreaves, G. Defining and using reference evapotranspiration. J. Irrig. Drain. Eng. 120, 1132–1139, doi: 10.1061/(ASCE)0733-9437(1994)120:6(1132) (1994).

Zang, C. & Biondi, F. treeclim: an R package for the numerical calibration of proxy-climate relationships. Ecography 38, 431–436, doi: 10.1111/ecog.01335 (2015).

Lefcheck, J. S. piecewiseSEM: Piecewise structural equation modelling in R for ecology, evolution, and systematics. Methods in Ecology and Evolution 7, 573–579, doi: 10.1111/2041-210X.12512 (2016).

Shipley, B. Confirmatory path analysis in a generalized multilevel context. Ecology 90, 363–368, doi: 10.1890/08-1034.1 (2009).

Grace, J. B. Structural Equation Modeling and Natural Systems. (Cambridge University Press, 2006).

Zuur, A. F ., Ieno, E. N ., Walker, N ., Saveliev, A. A. & Smith, G. M. Mixed effects models and extensions in ecology with R. (Springer, 2009).

Pinheiro, J., Bates, D., DebRoy, S. & Sarkar, D. Linear and Nonlinear Mixed Effects Models. nlme R package version 3.1-113. (2013).

Pettitt, A. N. A non-parametric approach to the change-point problem. J. R. Stat. Soc. 28, 126–135, doi: 10.2307/2346729 (1979).

Yue, S., Pilon, P., Phinney, B. & Cavadias, G. The influence of autocorrelation on the ability to detect trend in hydrological series. Hydrol. Process. 16, 1807–1829, doi: 10.1002/hyp.1095 (2002).

R. Core Team . R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria. https://www.R-project.org/. (2015).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by a Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory Climate Center grant and by the National Science Foundation grant no. PLR 15-04134. M.L. was supported by an Early and Advanced Postdoc Mobility Fellowships from the Swiss National Science Foundation (project numbers: P2EZP2_152213 and P300P2_164637). L.A.H. was supported by Columbia University’s Center for Climate and Life. We thank Kevin Griffin and Angelica Patterson for help with site selection, William Schuster and the Black Rock Forest Consortium for sampling authorization, and Marc Macias Fauria, Caroline Leland, and Steve Voelker for helpful comments. We acknowledge the National Atmospheric Deposition Program and the PRISM Climate Group for providing deposition and climate data. This paper is Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory contribution no. 8097.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.L., L.A.H. and N.P. designed the study. M.L. generated the tree-ring width and isotopic data, carried out data analyses, and wrote the manuscript. All authors contributed to analysis interpretation and manuscript development.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Levesque, M., Andreu-Hayles, L. & Pederson, N. Water availability drives gas exchange and growth of trees in northeastern US, not elevated CO2 and reduced acid deposition. Sci Rep 7, 46158 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep46158

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/srep46158

This article is cited by

-

Scots pine responses to drought investigated with eddy covariance and sap flow methods

European Journal of Forest Research (2023)

-

Tree-ring cellulose δ18O records similar large-scale climate influences as precipitation δ18O in the Northwest Territories of Canada

Climate Dynamics (2022)

-

Increased water use efficiency leads to decreased precipitation sensitivity of tree growth, but is offset by high temperatures

Oecologia (2021)

-

Climate and atmospheric deposition effects on forest water-use efficiency and nitrogen availability across Britain

Scientific Reports (2020)

-

Tree-ring isotopes capture interannual vegetation productivity dynamics at the biome scale

Nature Communications (2019)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.