Abstract

Methylation has frequently been implicated in gender determination in plants. The recent discovery of the sex determining region (SDR) of balsam poplar, Populus balsamifera, pinpointed 13 genes with differentiated X and Y copies. We tested these genes for differential methylation using whole methylome sequencing of xylem tissue of multiple individuals grown under field conditions in two common gardens. The only SDR gene to show a marked pattern of gender-specific methylation is PbRR9, a member of the two component response regulator (type-A) gene family, involved in cytokinin signalling. It is an ortholog of Arabidopsis genes ARR16 and ARR17. The strongest patterns of differential methylation (mostly male-biased) are found in the putative promoter and the first intron. The 4th intron is strongly methylated in both sexes and the 5th intron is unmethylated in both sexes. Using a statistical learning algorithm we find that it is possible accurately to assign trees to gender using genome-wide methylation patterns alone. The strongest predictor is the region coincident with PbRR9, showing that this gene stands out against all genes in the genome in having the strongest sex-specific methylation pattern. We propose the hypothesis that PbRR9 has a direct, epigenetically mediated, role in poplar sex determination.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The majority of flowering plants are cosexual (hermaphrodite or monoecious), in marked contrast to animals, which tend to have unisexual individuals. However some 6–7% of flowering plants do have separate sexes (i.e. are dioecious)1. These instances of dioecy are scattered across flowering plant clades, and dioecy in plants has many separate origins from an ancestral cosexual condition. Flowering plants are therefore a promising group in which to study the origin and mechanisms of sex determination and the development of sex chromosomes2,3,4,5. Some recent progress has been made recently in understanding the diverse molecular mechanisms of sex determination in flowering plants. In monoecious plants a single factor can be key in the development of unisexual flowers, as in melon (Cucumis melo), where an ethylene biosynthesis gene is the key determinant6. In monoecy, flowers of different sexes are present on the same individual. When dioecy evolves from monoecy, as in Diospyros and Populus, the determinant of floral sex must become associated with a segregating genomic region, thus becoming a sex locus. In Diospyros a small RNA is a likely candidate for the key determinant7. In Populus the functional molecular basis has yet to be elucidated.

Sexually specific patterns of methylation have frequently been implicated in plant sex determination8,9,10,11. In the genus Populus (poplars and aspens) methylation has also been implicated in work using the Chinese white poplar (an aspen relative), Populus tomentosa Carrière12.

The first detailed characterization of the sex-determining region (SDR) in Populus13 pinpointed 13 genes in a compact non-recombining region with a XX/XY architecture. This SDR has the same genomic architecture in P. trichocarpa Torr. & Gray, P. balsamifera L. and P. deltoides W. Bartram ex Marshall, but is different in aspen (P. tremuloides Michx)13,14.

To test the hypothesis that sex-specific methylation patterns may be involved in the vegetative-phase establishment of sexual differentiation in Populus, we wished to examine whole genome methylation patterns of vegetative tissue (xylem) in relation to sex and in particular the methylation status of all the genes identified at the Populus sex-locus by Geraldes et al.13. Xylem was chosen as it is a consistent tissue type with very little phenotypic plasticity (unlike leaves).

Results

PbRR9 is the only gene in the P. balsamifera genome to show strong sex-specific methylation patterns

Overall we detected expected amounts of DNA methylation across the genome. Taking all the samples (Table 1, S1) together we studied over 49 trillion potential cytosine methylation contexts (CG,CHG, CHH) of which 16.7% were methylated (Table S2). Of the methylated positions genome-wide, roughly equal numbers were in CG, CHG and CHH contexts (30.5, 32.3% and 36.7% respectively; Table S3).

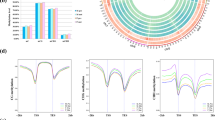

We next examined all the genes identified at the sex locus by Geraldes et al.13 for patterns of sex-specific methylation (Figs S1–3). Only one of these genes showed a distinct pattern of sex-specific DNA methylation: the two component response regulator 9 (PbRR9, Potri.019G133600). PbRR9 is the apparent ortholog of the two Arabidopsis genes ARR16 (AT2G40670) and ARR17 (AT3G56380). All these genes are members of the type-A subfamily, which is generally considered to form part of the network transducing cytokinin signals15,16. We determined that PbRR9 has a marked and significant pattern of differential DNA methylation between the sexes for all methylation contexts (Figs 1, 2 and 3). Figure 2 gives a more detailed breakdown specifically for the example of the CG context. The sex-specific methylation patterns were consistent across the two different environments (northern and southern common gardens) and thus appears to be constitutive.

Pink = female; blue = male. There is strong sex-specific methylation in the putative promoter region and in intron 1. In addition there is strong non-sex-specific methylation in intron 4. Asterisks indicate a significant difference between male and female samples (Q < 0.001, logistic regression test (Akalin et al.42), n = 18–24, methylation difference >20%).

We also surveyed sex-specific DNA methylation genome-wide both directly (data not shown) and by using machine learning (see below) to predict gender from genome-wide methylation patterns. We performed this analysis separately for all DNA methylation contexts. Although relatively weak signals of sex-specific methylation are detectable from across the genome (1376 features) the region of the genome coincident with PbRR9 gives by far the most prevalent contribution to the predictive signal (Fig. 4, right). This clearly indicates that PbRR9 is the gene that shows the strongest signal of sex-specific methylation pattern under our experimental conditions.

Left: Using statistical learning, gender (red: female, black: male) of test individuals (triangles) was assigned accurately on the basis of a training set (circles). The two-dimensional projection of the DNA methylome data shows group centroids of the predictors 1 and 2 for the discrimination of male and female samples on the x- and y axes. Right: To assess robustness and stability of the gender classification, the statistical learning algorithm (PLR) was run multiple times (5 fold cross validation, 50 iterations). Genomic regions whose methylation signatures were selected for modelling are visualized in the graphical representation of the genome (19 chromosomes of the poplar genome, all scaffolds were concatenated into a single unit). The shade of the color indicates the frequency with which features were repeatedly included in the PLR model for gender prediction (F4 > 80%: F3: ≤80%, F2: ≤20%, F1: ≤10% of all meta-features). The darker the marker, the greater the utility in prediction. The only marker in black is the one marking the region of the genome coincident with the PbRR9 gene. This plot shows the results for CG methylation: CHG and CHH contexts show nearly identical results.

Strong sex-biased DNA methylation is characteristic of the promoter and intron 1 regions

Looking at DNA methylation across the PbRR9 gene, some striking patterns are immediately evident (Figs 1, 2 and 3). First, this gene is apparently both “promoter methylated” and “gene body methylated” (i.e. the methylation is in sites of the potential promoter region and in transcribed parts of the gene, mostly the introns), Methylation can be strong in the proximal region close to the transcription start site showing up to 90% methylation (Figs 1, 2 and 3). In addition, methylation occurs in the first and the fourth introns to an extent that is higher than the genome average for intron regions17,18. Secondly, in general the males are more heavily methylated than the females (Figs 1, 2 and 3), although there is one cytosine of the putative promoter region where this pattern is reversed. The regions of greatest sex-specific methylation bias are the putative promoter region and intron 1 (the latter has strong male-specific methylation). The concentration of methylation at the 5-prime end of the gene is consistent with control regions generally being found in the first intron19 and 5-prime to the gene (promoter region). In Arabidopsis only about 5% of expressed genes are methylated at the proximal promoter20,21, but promoter methylation is well known to influence transcription22.

DNA Methylation patterns can be used to assign genders by machine learning algorithms

Knowing the sex of individual poplar trees has allowed us to determine a strong sex bias in methylation at a single locus. Now we ask the question, can knowing the genome-wide pattern of methylation allow us to determine tree gender? Using 70% of the samples as a training set (Tables S1 and S4), the methylation patterns of pseudo-unknown trees were then used to predict gender. With over 200,000 input features (see Methods), a set of meta-features, i.e. feature groups whose collective methylation patterns are highly informative, were useful as predictors and comprised ca. 60 individual features (Table 2). Figure 4 (left) shows that accurate assignment to the correct gender cluster was easily achieved from genome wide methylation pattern. A large number of genome regions were weakly predictive of gender from their methylation, although some of these may represent random effects or small partial contributions due to the large number of genome regions tested. However, one region was very strongly predictive of gender: the sex-determining region on chromosome 19. On this chromosome the number of recurrent predictive features, is considerably higher than on other chromosomes, especially when taking chromosome length and cluster prevalence (37 vs. 3–9, Table 3) into account. This is where gene PbRR9 is located (Fig. 4, right), and PbRR9 has the strongest differential methylation signal of all genes in this region. This confirms PtRR9 as a standout gene, among all the c. 45,000 poplar genes, whose methylation is strongly predictive of gender.

Discussion

Is sex in poplar controlled epigenetically?

As the SDR on chromosome 19 is the only part of the genome that segregates with gender, a gene or genes in this region must ultimately control gender. Geraldes et al.13 first characterized this region, and on the basis of a genome-wide association study (GWAS) using version 2.2 of the genome (the version of the genome that assembles the sex locus least poorly) determined 13 genes at the SDR. One of these genes was methyltransferase 1 (MET1), a cytosine methyltransferase. The presence of this gene at the SDR raises the possibility that sex-specific DNA methylation mediated, in some unknown way, by the male (Y) allele of met1 might be responsible for sex-specific methylation of genes in any part of the genome. However now that sex-specific methylation has been examined we know that the strongest signal of such methylation is at the SDR itself, PbRR9. We therefore have an SDR with a sexually differentiated methyltransferase and a sexually differentiated methylation target, raising the possibility that sex-biased methylation of PbRR9 might be controlled in cis or trans or both.

Our study was highly targeted in that it looked for sex-specific DNA methylation in a vegetative tissue (xylem) with no sexual phenotype. This is to test the hypothesis that sex-specific methylation patterns may be involved in the pre-reproductive establishment of sexual development. It would be of interest to examine sex-specific methylation in other tissues including reproductive ones. However, the problem of using reproductive tissue is that they differ in physiology, biochemistry and morphology between sexes, so differences in methylation may be due to the sex of the individual, or merely to tissue differences between the tested organs. Testing a non-sexually differentiated tissue allows determination of constitutive sex differences and establishes that DNA methylation is a marker of sex in tissues that have no phenotypic indications of sex, i.e. the methylome precedes the phenotype as a marker of sex.

PbRR9 is potentially a master regulator of poplar gender

The sex-specific methylation patterns of PbRR9 could be coincidental or responsible merely for secondary sexual characteristics of little relevance to sex determination. However, this gene has a number of features that make a direct role in sex-determination plausible. Type-A two component response regulators are a moderately-sized family of transcriptional activators with a variety of developmental effects23,24,25,26,27 and so could plausibly trigger a developmental cascade leading to alterations in inflorescences. A previous study in poplar have shown that PbRR9 is only weakly expressed in vegetative tissue but is strongly expressed in catkins25 but only female catkins were tested in that study. Many RR genes are known to be part of cytokinin signal transduction. Cytokinins are involved in early inflorescence development28 and may thus be part of the inflorescence-specific activation of PbRR9.

The hypothesis that PbRR9 is directly involved in poplar gender determination clearly deserves to be tested further, especially by detailed expression studies of this gene against the background of reproductive development. A fine-scale study of differential expression against the trajectory of inflorescence development, involving microdissection of inflorescence primordia, would be ideal. It is however, beyond the scope of the present paper. Identifying downstream targets of this gene and assessing the phenotype of plants in which this gene has been misregulated, for instance by VIGS or CRISPR/Cas9 genome editing, would also be obvious possibilities.

Could tree sex be reversed by demethylation?

The finding of sex-specific patterns of DNA methylation raises the possibility that inflorescence sex could be altered by hypomethylating chemical treatment, such as by 5-azacytidine29 or zebularine30. Such an approach has been applied in Silene9 in which application of 5-azacytidine (5-azaC) induced a sex change in a number of male plants, while having no effect in females. Such induced sex changes, even if limited to single inflorescences, have some significance for plant genetics and breeding as they potentially allow selfing, which is not normally possible in dioecious trees. It has long been known that sex is labile in poplars: a number of cases of naturally occurring intersexes have been observed31,32,33. Given the results reported here, the possibility arises that some of these intersexes may result from hypomethylation mutations. As far as we are aware, as yet no attempts have been made to induce sexual abnormalities in poplar with chemical hypomethylation, but the idea is open to test.

Methods

Source of P. balsamifera tissue samples

DNA methylation patterns can vary according to genotype and environmental conditions and so careful replication was used in the experiemntal design, with multiple genetic individuals and multiple sites. The material sequenced consisted of genomic DNA from xylem tissue collected from multiple genotypes in replicate from two environmentally divergent common gardens34. The common gardens are located at Prince Albert (PA - 53.62°N 106.43°W; elevation 461 m) and Indian Head (IH - 50.52°N 103.68°W; elevation 605 m), Saskatchewan, Canada and comprise provenances of P. balsamifera that were collected throughout the natural range of this species. Two common gardens were used to ascertain the effect of between-site differences in environment on the methylation patterns observed. A fully randomised design was used for the common gardens to eliminate any within-site systematic environmental effects on phenotype or epigenome. The collection of P. balsamifera genotypes used here, the AgCanBaP collection of the Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada (AAFC), has been previously described35. Genotypes were sexed phenotypically at flowering, or by using genetic sex-tests as described in Geraldes et al.13. The list of genotypes (and environment of origin) used is given in Table 1 (and further details in Table S1).

Tissue was harvested in the field from small branches of P. balsamifera (c. 1–2 cm diam.) from the north-exposed side of the tree. The bark was peeled, and the soft tissue inside (the external layer of the wood cylinder, developing xylem) was scraped off with a razor blade and immediately stored on dry ice. Tissue was harvested on five consecutive days in the field at the end of July in 2013 (PA: July 25th and 26th; IH: July 27–29). For consistency, tissue was harvested only during the first half of the day (10 am–2 pm). Xylem was chosen as it is a consistent and homogeneous tissue that has little phenotypic plasticity with environment (unlike leaves).

P. balsamifera is the sister species of the fully sequenced P. trichocarpa which has been the subject of extensive variation studies36,37. There is very little difference between the species at the molecular level and there is no difference in the architecture of the sex determining region13. Therefore P. trichocarpa gene annotations are used throughout.

Bisulphite sequencing

Genomic DNA was extracted according to Doyle and Doyle38 and subjected to whole genome bisulfite sequencing (WGBS). WGBS was performed essentially as described in Lister et al.39. Libraries were generated using a target insert size of 300 bp and original Illumina adapters. Paired-end sequencing was performed on a HiSeq2500 (Illumina) at 125 cycles per end and by multiplexing 2 samples per lane at the Genome Science Centre, Vancouver British Columbia, Canada.

Analysis of DNA methylation patterns

Quality and adapter trimmed reads40 were mapped to the P. trichocarpa reference genome (v3.0, http://phytozome.net) using the three-letter aligner Bismark v0.12.541. Reads were mapped against in silico bisulfite converted and non-converted genome sequences, and methylation ratios for each cytosine position were determined as #Cs/(#Cs + #Ts). Downstream processing and calculation of differential methylation was done in R for CG, CHG, and CHH contexts separately42,43. Pre-filtering included coverage-based selection for bases with coverage >10×. Differential methylation between male and female samples was calculated, and in CG context features with differential methylation of at least 25% and q < 0.001 were selected42.

Sex prediction from DNA methylation by machine-learning

For statistical modeling of methylation patterns on gender, methylation information was summarized across the genome for tiles (features) of 500 bp length. Filtering for statistical learning included selection of variable features with higher than median inter-quartile range that were detected in 80% of the samples, i.e. features with little variation across samples were excluded. This retained a total of 243197 features for use in supervised classification. Penalized logistic regression (PLR) implemented in program pelora44 has been developed as an effective means of classification in microarray analyses and was shown to demonstrate excellent predictive potential44,45,46. The pelora classifier integrates feature selection, supervision and sample classification using a forward selection approach with recurrent pruning steps and a l2-penalized negative log-likelihood function44. Importantly, it identifies groups of features, i.e. clusters or meta-features that collectively contribute to robust outcome variable prediction. Here, PLR was employed to model gender on DNA methylation data. The predictive potential was evaluated using 5 fold cross validation with 50 iterations across 30 randomly selected xylem samples that comprised the training set (random selection by genotype, split1, Table S1). An alternative training set selection (completely random, split2) yielded comparable results. Suitable parameters were selected to identify the most parsimonious model with accurate prediction potential (Table S4). Independent model evaluation was done using separate sets of test samples (Table S1). Leading meta-features were then merged for detailed downstream analyses.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Bräutigam, K. et al. Sexual epigenetics: gender-specific methylation of a gene in the sex determining region of Populus balsamifera. Sci. Rep. 7, 45388; doi: 10.1038/srep45388 (2017).

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

Renner, S. S. & Ricklefs, R. E. Dioecy and its correlates in the flowering plants. American Journal of Botany 82, 596–606 (1995).

Charlesworth, D. Plant contributions to our understanding of sex chromosome evolution. New Phytologist 208, 52–65 (2015).

Charlesworth, D. Plant sex chromosomes. Annual Review of Plant Biology 67, 397–420 (2016).

Filatov, D. A. Homomorphic plant sex chromosomes are coming of age. Molecular Ecology 24, 3217–3219 (2015).

Harkess, A. & Leebens-Mack, J. A century of sex determination in flowering plants. Journal of Heredity, esw060 (2016).

Boualem, A. et al. A conserved mutation in an ethylene biosynthesis enzyme leads to andromonoecy in melons. Science 321, 836–838 (2008).

Akagi, T., Henry, I. M., Tao, R. & Comai, L. A Y-chromosome–encoded small RNA acts as a sex determinant in persimmons. Science 346, 646–650 (2014).

Gorelick, R. Evolution of dioecy and sex chromosomes via methylation driving Muller’s ratchet. Biological Journal of the Linnean Society 80, 353–368 (2003).

Janoušek, B., Široký, J. & Vyskot, B. Epigenetic control of sexual phenotype in a dioecious plant, Melandrium album. Molecular and General Genetics [MGG] 250, 483–490 (1996).

Zhang, W., Wang, X., Yu, Q., Ming, R. & Jiang, J. DNA methylation and heterochromatinization in the male-specific region of the primitive Y chromosome of papaya. Genome Research 18, 1938–1943 (2008).

Martin, A. et al. A transposon-induced epigenetic change leads to sex determination in melon. Nature 461, 1135–1138 (2009).

Song, Y. et al. Sexual dimorphic floral development in dioecious plants revealed by transcriptome, phytohormone, and DNA methylation analysis in Populus tomentosa. Plant Molecular Biology 83, 559–576 (2013).

Geraldes, A. et al. Recent Y chromosome divergence despite ancient origin of dioecy in poplars (Populus). Molecular Ecology 24, 3243–3256 (2015).

Pakull, B., Kersten, B., Lüneburg, J. & Fladung, M. A simple PCR‐based marker to determine sex in aspen. Plant Biology 17, 256–261 (2015).

To, J. P. et al. Cytokinin regulates type-A Arabidopsis response regulator activity and protein stability via two-component phosphorelay. The Plant Cell 19, 3901–3914 (2007).

Ren, B. et al. Genome-wide comparative analysis of type-A Arabidopsis response regulator genes by overexpression studies reveals their diverse roles and regulatory mechanisms in cytokinin signaling. Cell Research 19, 1178–1190 (2009).

Feng, S. et al. Conservation and divergence of methylation patterning in plants and animals. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 107, 8689–8694 (2010).

Liang, D. et al. Single-base-resolution methylomes of Populus trichocarpa reveal the association between DNA methylation and drought stress. BMC Genetics 15, S9 (2014).

Rose, A. B. In Nuclear pre-mRNA processing in plants 277–290 (Springer, 2008).

Zhang, X. et al. Genome-wide high-resolution mapping and functional analysis of DNA methylation in Arabidopsis. Cell 126, 1189–1201 (2006).

Cokus, S. J. et al. Shotgun bisulphite sequencing of the Arabidopsis genome reveals DNA methylation patterning. Nature 452, 215–219 (2008).

Lou, S. et al. Whole-genome bisulfite sequencing of multiple individuals reveals complementary roles of promoter and gene body methylation in transcriptional regulation. Genome biology 15, 1 (2014).

Immanen, J. et al. Characterization of cytokinin signaling and homeostasis gene families in two hardwood tree species: Populus trichocarpa and Prunus persica. BMC genomics 14, 885 (2013).

Immanen, J. et al. Cytokinin and auxin display distinct but interconnected distribution and signaling profiles to stimulate cambial activity. Current Biology 26, 1990–1997 (2016).

Ramírez-Carvajal, G. A., Morse, A. M. & Davis, J. M. Transcript profiles of the cytokinin response regulator gene family in Populus imply diverse roles in plant development. New Phytologist 177, 77–89 (2008).

Hellmann, E., Gruhn, N. & Heyl, A. The more, the merrier: cytokinin signaling beyond Arabidopsis. Plant Signaling & Behavior 5, 1384–1390 (2010).

Pils, B. & Heyl, A. Unraveling the evolution of cytokinin signaling. Plant Physiology 151, 782–791 (2009).

Han, Y., Yang, H. & Jiao, Y. Regulation of inflorescence architecture by cytokinins. Frontiers in Plant Science 5, 669–669 (2013).

Jones, P. A. & Taylor, S. M. Cellular differentiation, cytidine analogs and DNA methylation. Cell 20, 85–93 (1980).

Baubec, T., Pecinka, A., Rozhon, W. & Mittelsten Scheid, O. Effective, homogeneous and transient interference with cytosine methylation in plant genomic DNA by zebularine. The Plant Journal 57, 542–554 (2009).

Song, Y., Ma, K., Ci, D., Zhang, Z. & Zhang, D. Sexual dimorphism floral microRNA profiling and target gene expression in andromonoecious poplar (Populus tomentosa). PLoS One 8, e62681 (2013).

Stettler, R. F. Variation in sex expression of black cottonwood and related hybrids. Silvae Geneticae 20, 42–46 (1971).

Lester, D. T. Variation in sex expression in Populus tremuloides Mich. Silvae Geneticae 12, 141–151 (1963).

Soolanayakanahally, R. Y., Guy, R. D., Silim, S. N. & Song, M. Timing of photoperiodic competency causes phenological mismatch in balsam poplar (Populus balsamifera L.). Plant, Cell and Environment 36, 116–127 (2013).

Soolanayakanahally, R. Y., Guy, R. D., Silim, S. N., Drewes, E. C. & Schroeder, W. R. Enhanced assimilation rate and water use efficiency with latitude through increased photosynthetic capacity and internal conductance in balsam poplar (Populus balsamifera L.). Plant, Cell and Environment 32, 1821–1832 (2009).

Geraldes, A. et al. Landscape genomics of Populus trichocarpa: the role of hybridization, limited gene flow, and natural selection in shaping patterns of population structure. Evolution 68, 3260–3280 (2014).

McKown, A. D. et al. Geographical and environmental gradients shape phenotypic trait variation and genetic structure in Populus trichocarpa. New Phytologist 201, 1263–1276 (2014).

Doyle, J. J. & Doyle, J. L. Isolation of plant DNA from fresh tissue. Focus 12, 13–15 (1990).

Lister, R. et al. Highly integrated singe-base resolution maps of the epigenome in Arabidopsis. Cell 133, 523–536 (2008).

Bolger, A. M., Lohse, M. & Usadel, B. Trimmomatic: a flexible trimmer for Illumina sequence data. Bioinformatics 30, 2114–2120 (2014).

Krueger, F. & Andrew, S. R. Bismark, a flexible aligner and methylation caller for Bisulfit-Seq applications. Bioinformatics 27, 1571–1572 (2011).

Akalin, A. et al. methylKit: a comprehensive R package for the analysis of genome-wide DNA methylation profiles. Genome Biology 13, R87 (2012).

R Core Team . R: A language and environment for statistical computing, https://www.R-project.org/ (2016).

Dettling, M. & Bühlmann, P. Finding predictive gene groups from microarray data. Journal of Multivariate Analysis 90, 106–131 (2004).

Wachtel, M. et al. Gene expression signatures identify rhabdomyosarcoma subtypes and detect a novel t (2; 2) (q35; p23) translocation fusing PAX3 to NCOA1. Cancer Research 64, 5539–5545 (2004).

Yang, X., Lee, Y., Fan, H., Sun, X. & Lussier, Y. A. Identification of common microRNA-mRNA regulatory biomodules in human epithelial cancer. Chinese Science Bulletin 55, 3576–3589 (2010).

Acknowledgements

Funding for this work was provided from the Genome Canada Large-Scale Applied Research Project (POPCAN: Project 168BIO to MMC, SDM, CJD and QC) and the University of Toronto. RS was funded by Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada. We thank Dr Armando Geraldes for insightful comments and helpful discussion.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

K.B. performed the analyses, contributed to the planning of the study, collected samples and co-wrote the paper; M.M.C. contributed to the analysis of data; R.S. provided access to poplar genetic material and information on field-sexing of individuals; S.D.M. provided scientific leadership, contributed to the choice of material for sequencing and secured funding; C.J.D. contributed to the planning of the study and secured funding; M.M.C. provided scientific leadership, contributed to the planning of the study and secured funding; Q.C. contributed to data interpretation, co-wrote the paper and secured funding for the study.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Bräutigam, K., Soolanayakanahally, R., Champigny, M. et al. Sexual epigenetics: gender-specific methylation of a gene in the sex determining region of Populus balsamifera. Sci Rep 7, 45388 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep45388

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/srep45388

This article is cited by

-

Reciprocal expression of MADS-box genes and DNA methylation reconfiguration initiate bisexual cones in spruce

Communications Biology (2024)

-

Gender specific SNP markers in Coscinium fenestratum (Gaertn.) Colebr. for resource augmentation

Molecular Biology Reports (2024)

-

Comparative transcriptomic analysis of male and females in the dioecious weeds Amaranthus palmeri and Amaranthus tuberculatus

BMC Plant Biology (2023)

-

Sex-specific DNA methylation: impact on human health and development

Molecular Genetics and Genomics (2022)

-

Genome-wide association mapping uncovers sex-associated copy number variation markers and female hemizygous regions on the W chromosome in Salix viminalis

BMC Genomics (2021)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.