Abstract

Nowadays, the multi-crystalline silicon (mc-Si) solar cells dominate the photovoltaic industry. However, the current acid etching method on mc-Si surface used by firms can hardly suppress the average reflectance value below 25% in the visible light spectrum. Meanwhile, the nitric acid and the hydrofluoric contained in the etching solution is both environmental unfriendly and highly toxic to human. Here, a mc-Si solar cell based on ZnO nanostructures and an Al2O3 spacer layer is demonstrated. The eco-friendly fabrication is realized by low temperature atomic layer deposition of Al2O3 layer as well as ZnO seed layer. Moreover, the ZnO nanostructures are prepared by nontoxic and low cost hydro-thermal growth process. Results show that the best passivation quality of the n+ -type mc-Si surface can be achieved by balancing the Si dangling bond saturation level and the negative charge concentration in the Al2O3 film. Moreover, the average reflectance on cell surface can be suppressed to 8.2% in 400–900 nm range by controlling the thickness of ZnO seed layer. With these two combined refinements, a maximum solar cell efficiency of 15.8% is obtained eventually. This work offer a facile way to realize the environmental friendly fabrication of high performance mc-Si solar cells.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Since year 2002, the multi-crystalline silicon (mc-Si) solar cells have become the mainstream products in most photovoltaic (PV) industrial production lines1,2. Recently, mc-Si solar cells have dominated more than 70% of the PV industry3. However, the average conversion efficiency (CE) of the mc-Si solar cells is still ~2% lower than that of the single crystalline silicon (sc-Si) based solar cell4. One main obstacle is the poor light trapping ability of the mc-Si based solar cells in the photo-active layers5. For the further CE improvement of the mc-Si solar cells, the front texture and antireflection coating play an important role by increasing light coupling into the active region of the devices. It is known that a pyramid texture is not applicable to the mc-Si wafer, although it can be formed on sc-Si wafer based on anisotropic alkali etching to minimize the optical reflection losses. The current texturing way for reducing surface reflectance on the mc-Si wafer used in industry is generally utilizing isotropic texturing in acidic solution containing nitric acid (HNO3) and hydrofluoric acid (HF) to form randomly overlapping hemispherical pits. However, this kind of etching method can hardly suppress the average reflectance (R) value below 25% in visible light spectrum5. That is much higher than the ~12% R value of the alkaline etched sc-Si surface. In addition, the HNO3 and HF contained in the texturing solution for mc-Si is both not eco-friendly as well as highly toxic to human skin and bone.

To efficiently suppress the optical reflection losses, the Si nanostructures (NS) formed by metal-catalyzed-etching (MCE)6,7,8, laser ablation9,10 and reactive-ion-etching (RIE)5,11,12,13,14 on mc-Si substrates have been proposed, which can achieve <5% reflectance over a wide spectral range (400–1100 nm) in combination with an SiNx anti-reflection coating. Based on these methods, the obtained mc-Si solar cells with highest conversion efficiency (CE) of 18%3, 19.1%10 and 20.3%12 have been reported. Unfortunately, the MCE technique is [001] oriented silicon preferred15,16,17,18, which is not very effective on the mc-Si surface. Because the formed Si NS is unable to distribute homogeneously on the surface owning to the random crystalline characteristic of the mc-Si, the light trapping ability will be degrade19. Meanwhile, the AgNO3 contained in the etching solution is not cost effective. On the other hand, although the laser ablation and RIE method can be performed on both sc-Si and mc-Si surface, the high cost and low production rate makes them hard to be suitable for industrial production. More seriously, the required etching gas of SF6/Cl25 is a threat to cause ozone hole or highly toxic to human. In recent years, the ZnO NS has aroused increasing attention for anti-reflection applications due to its low cost, good transparency, appropriate refractive index20,21,22,23,24. In contrast to Si NS, Green et al. reported that the ZnO NS can be grown on arbitrary substrates, regardless of the substrate crystallinit25. Lee et al. systematically investigated the light trapping ability of the ZnO NS with different morphologies26. Their results show that the optimized ZnO NSs as the anti-reflection layer for Si solar cell exhibit a superior light harvesting ability to that of the conventional SiNx coating. More importantly, the ZnO NS can be grown in large scale by a simple and low cost hydro-thermal method27. In addition, the utilized reagents including zinc nitrate and hexamethylene tetraamine (HMT) to grow ZnO NS are nontoxic and at a very low concentration of 1–100 mM. The merits of the fabricating ZnO NS mentioned above pave a way for its environmental-friendly application on the mc-Si solar cells.

In the past decade, there have been application of ZnO NS on amorphous-Si (a-Si)28,29,30, mc-Si31,32, sc-Si33,34,35, GaAs36 and heterojunction37 solar cells, with CE ranges from 5.2% to 16.4%. In 2010, Chen et al. firstly utilized the vertically aligned ZnO nano-rod arrays as the anti-reflection layer in a mc-Si solar cell application31. Although an improved CE from 10.4% to 12.8% was obtained. It was still much lower than the ~18% CE value of the commercial available mc-Si solar cells. The main problem is the relatively low Voc of ~550 mV Chen’s cell compared to those of SiNx coated commercial cells (typically ~620 mV). This was mainly due to the high surface recombination rate on Si surface when ZnO NS grow directly on the Si wafer. To improve the Si surface passivation quality, Liu et al. prepared a thermal oxidation layer on the micro-pyramid sc-Si wafers before the formation of the ZnO NS34. This novel hierarchical structure shows a broadband reflection suppression in the 300–1200 nm rage, with an average weighted reflectance of 3.2%. An enhanced CE of 16% was achieved for the screen-printed sc-Si based solar cell. But the required SiO2 passivation layer formation temperature of 900 °C would led to huge energy consumption. Lin et al. reported an efficient broadband and omnidirectional light-harvesting scheme employing a ZnO nanorod/Si3N4-coated Si microgroove on 5-inch sc-Si solar cells. The processing temperature for the growth of the passivation layer was then decreased to ~450 °C through replacing the thermal grown SiO2 layer by plasma-enhanced-chemical-deposition (PECVD) grown SiNx layer35. Unfortunately, the Si surface passivation quality was sacrificed, leading to a reduced solar cell conversion efficiency of 14.04%. It should be also noted that the preparations of the passivation layer and the ZnO seed layer were accomplished by the different machines for the above two mentioned solar cells. This would apparently increase the process complexity at the mass production level.

Encouragingly, the atomic-layer-deposition (ALD) technique has recently received great attention in the PV industry, which can be a potential solution to the problems. Taking the advantage of its relatively low growth temperate (around 200 °C)38,39, the heat budget to prepare the passivation layer by ALD can be reduced accordingly. It is reported that the ALD grown Al2O3 film exhibits the excellent passivation quality on the surface of the p-type Si solar cell owing to the fixed charge inside the prepared film40,41,42,43,44,45,46. Furthermore, the investigations reveal that the Al2O3 film also show good passivation ability on the n+ emitter of the p-Si solar cells47,48. But the ALD processing parameters including the Al2O3 film thickness as well as the followed annealing temperature have not been optimized. On the other hand, the seed layer of the ZnO NS can also be grown by ALD in the same reactor, which can simplify the fabrication process significantly. The hierarchical structure based on ZnO NS/Al2O3 passivation layer is then proposed to enhance the light trapping ability and improve the CE of the mc-Si solar cells.

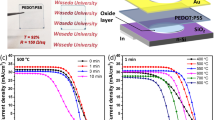

In this work, a mc-Si solar cell based on ZnO NS and an Al2O3 passivation layer is demonstrated. As illustrated in Fig. 1, the ZnO NS are utilized to promote the light absorption into the mc-Si substrate. Meanwhile, the poor passivation ability of ZnO NS on the silicon surface is compensated by adding an Al2O3 passivation layer between the ZnO NS and the mc-Si. To realize the eco-friendly fabrication, the Al2O3 passivation layer as well as the seed layer for the growth of ZnO NS are all prepared by the low temperature ALD growth technique. After that, the ZnO NS are prepared by a conventional hydro-thermal growth method utilizing the nontoxic reagents. Both the Al2O3 layer passivation mechanism and the spectra absorption character of the ZnO NS are investigated deeply to achieve an optimized processing condition for the subsequent application in the mc-Si solar cell. It is found that there is a tradeoff between the Si surface dangling bond saturation level and the negative charge concentration in the Al2O3 passivation layer on the n+ -type mc-Si surface. The obtained solar cell with an optimized 12 nm-thick Al2O3 layer show an increment of 4.9% in the open circuit voltage (Voc) than that of the one with only ZnO NS. Furthermore, it is observed that the surface morphology as well as the antireflection character of the ZnO NS can be controlled by altering the thickness of the ZnO seed layer. A lowest average reflectance of 8.5% in 400~900 nm range can be achieved, leading to an increased solar cell performance in Jsc of 4.2 mA/cm2. Based on this hierarchical structure, a maximum CE value of 15.8% is obtained for the optimized mc-Si solar cell, which has a comparable performance to the previously reported sc-Si cell based on ZnO NS with a highest CE of 16.0%34. As a result, the findings of this work pave a facile way for realizing the eco-friendly fabrication and potential application of the high performance silicon solar cells in the future.

Results and Discussion

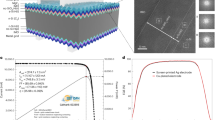

Optimization of the Al2O3 Passivation Layer

To realize the best passivation quality of the Al2O3 film, the minority carrier lifetime (τ) on the 70 Ω per square n+ doped mc-Si surface are investigated as a function of the Al2O3 film thickness (determined by the ALD growth cycles) as well as the annealing duration of the Al2O3/mc-Si stacks. The results are shown in Fig. 2. As is evidently shown in Fig. 2, the unannealed mc-Si/Al2O3 stacks and the annealed ones exhibit quite different variation tendency in τ. The τ of the unannealed stack exhibit a low τ of 40 μs. Then the τ value increases monotonically to 352 μs as the growth cycle of the Al2O3 reaches 800. While for the annealed stacks, the value of the Al2O3 growth cycle determines three different regions of the τ performance. For a given annealing duration, the τ increases (Region I) as the Al2O3 growth cycle increases from 0 to 75. A peak value of 425 μs is obtained by the 300 s annealed sample as the growth cycle reaches 75. Then the τ value decreases (Region II) as the growth cycle further increases from 75 to 200. Finally, a slight increase trend in τ is observed again at highest growth cycle (Region III). At each value of the growth cycle, the prolonged annealing time leads to a higher τ value in Region I and II. In contrast, the opposite trend is observed in Region III. For example, at the growth cycle of 75, the τ value of the samples increases from 193 μs to 425 μs as the annealing duration increases from 0 to 300 s. Oppositely, at the growth cycle of 800, the τ value decreases from 352 μs to 238 μs as the annealing duration increases. Furthermore, the passivation effect of the structure of Si/Al2O3/ZnO NS with 100 s Al2O3 annealing time is further checked by measuring its minority carrier lifetime. As shown in the violet line of Fig. 2, the minority carrier lifetime changes little after the formation of the ZnO NS on the mc-Si/Al2O3 sample. It indicated that the subsequent ZnO NS preparation has little effect on the passivation quality of the Al2O3 on the Si surface. As a result, the subsequent ellipsometry and C-V tests are just conduct on the substrates with only Al2O3 coating for obtaining more accurate SiO2 thickness and flat band voltages. Given consideration to both passivation quality as well as the heat budget, the 100 s annealed stack with 75 cycle Al2O3 growth (~12 nm thick and with a relatively high τ of 407 μs) is selected as the optimum process conditions for the following solar cell fabrication.

Further investigations are made to understand the passivation mechanism of the Al2O3 film with different thickness on the n+ doped mc-Si surface. During the annealing treatment on Si/Al2O3 stack, the excess oxygen inside the Al2O3 layer will diffuse to the Al2O3/Si interface and forms a SiO2 interlayer49. The SiO2 layer brings chemical passivation effect by saturating the dangling Si bonds on mc-Si surface41,45,49. As a result, the thickness of the SiO2 interfacial layer is analyzed. Before the annealing treatment, owning to the low growth temperature (200 °C) of the ALD-Al2O3, the SiO2 layer is unable to be recognized by the ellipsometer. Table 1 shows the thickness evolution of the SiO2 interfacial layer of the annealed Al2O3 samples with growth cycles increased from 50 to 200. After the annealing procedure, the thickness of the SiO2 layer evidently increases. As the Al2O3 growth cycles increases from 50 to 100, the thickness of the SiO2 increased by 57% (1.84 to 2.81 nm). At this moment, the increment of SiO2 (8.84 to 12.98 nm) coordinates with that of the Al2O3 film. However, as the growth cycles increased from 150 to 200 cycles, the thickness increment of the SiO2 greatly reduced to 7%, and 1%, respectively. It can be predicted that the thickness of the SiO2 layer will stand-still at ~3.1 nm at higher growth cycles. This phenomenon can be explained by the annealing condition of the all the Al2O3 samples are the same. So, the amount of the oxygen which can diffuse to the Si/Al2O3 interface is limited. Thus, the chemical passivation effect due to the formation of SiO2 layer is most effective at a relative low Al2O3 growth cycle ranging from 0 to 100. After that, the negative charge concentration of the Al2O3 films are investigated. Because the negative charges can lead to field passivation effect, which can impact the electron density at the mc-Si surface40,46,50. Figure 3a,b describes the C-V characteristics of the Mo/Al2O3/n+ -type mc-Si capacitor, in which the Al2O3 growth cycles ranges from 50 to 200. As shown in Fig. 3a, before annealing, the 50 cycles grown Al2O3 film exhibit electric break-down in accumulation capacitance owning to the relatively low film thickness. The C-V curves of the samples with 100–200 growth cycles exhibit a wide flat band hysteresis window, indicating a high interface trap density. We speculate this phenomenon is mainly caused by the existence of the Si dangling bonds at the mc-Si/Al2O3 interface. This observation corresponds with the poor τ performance of the unannealed Al2O3 samples shown in Fig. 2. After the annealing treatment, the forged SiO2 interfacial layer saturated most of the dangling Si bonds. In sequence, the flat band hysteresis windows of the samples are greatly narrowed in Fig. 3b. More importantly, as the Al2O3 growth cycles increases, their corresponding flat band voltage shifts toward positive direction, indicating a gradually increased negative charge concentration. One part of the negative charges come from the formation of the tetrahedrally coordinated Al site in the Al2O3 film after the annealing. Another part of the negative charges comes from the SiO2 interfacial layer45. For the p+ type silicon passivation, electrons are the minority carriers. The negative charges inside the Al2O3 film plays a positive role as it can prevent the electrons from diffusing to the surface of the p+ type Si surface. In our case, the negative charges plays a negative role, because it will accelerate the diffusion of the holes to the n+ type Si surface. The τ evolution in the three regions of Fig. 2 can be explained by the combined affection of the two passivation effects mentioned above. In region I, the chemical passivation by the formation of SiO2 layer dominates the passivation mechanism. Because at this moment, the thickness of the SiO2 increases quickly. Thus, more and more Si dangling bonds are saturated. Meanwhile, the negative charge concentration inside the passivation layer is low, the corresponding negative influence is minimized. As a result, the τ value increases quickly in region I. While in region II, the growth of the SiO2 layer stops, but the negative charge inside the Al2O3 layer continue to increase. In this situation, the field passivation effect plays the main role. Unfortunately, as is mentioned above, the negative charge concentration will accelerated the recombination rate on the n+ Si surface, the τ value decreases. At even higher Al2O3 growth cycles in region III, the increment of negative charge concentration is mainly contributed by the formation of Al2O3 at outer side film, which can hardly influence the holes inside the n+ type mc-Si. In consequence, the τ value gradually increases as a result of the increased thickness of the passivation layer. Results show that a thin Al2O3 layer can saturate most of the Si dangling bonds while eliminating the negative influence of negative charges on n+ doped Si. As a result, the best passivation quality is obtained.

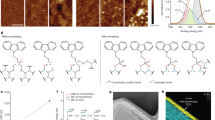

Optical Optimization of the ZnO NS

There have been many investments on anti-reflection character of the ZnO NS synthesized from spin-coated seed layer25,26,27. However, the film thickness cannot be controlled precisely by spin-coating. To overcome this difficulty, the precise film thickness control of the ZnO seed layer is achieved by ALD growth in this work, taking the advantage of the layer-by-layer growth mechanism of the ALD. The anti-reflection character of the ZnO NS synthesized from ALD grown seed layer with different thickness is systematically investigated in this work. At first, the crystallization behavior of the ALD grown ZnO seed layer is investigated because it will greatly affect the surface morphology of the later grown ZnO NS25. Figure 4 shows the XRD patterns of the ALD-ZnO seed layers with different growth cycles (ranging from 50 to 200) prepared on the surface of the optimized mc-Si/Al2O3 stack. The seed layer based on 50 growth cycles exhibit a weak ZnO (002) peak at 2θ = 34.4°, which shows that the as-deposited seed layer is mainly amorphous. As the seed layer growth cycle reaches 100, the ZnO (002) peak become stronger, indicating some small ZnO crystal grains started to form inside the seed layer. The calculated ZnO crystal grains size inside the seed layer using the Scherrer formula51 are summarized in Table S1 in the supporting information. The full-width half-maximum (FWHM) of the ZnO (100) peak decreases as the growth cycle increases, demonstrating a gradually increased grain size of the ZnO crystal form 14.2 to 31.7 nm in the seed layer. Figure 5a–d show the morphology evolution of the ZnO NS synthesized from the seed layers demonstrated in Fig. 4. As shown in Fig. 5a, the ZnO NS prepared on the 50 cycles grown seed layer exhibit a disordered morphology and distribution. One reason is the poor crystalline degree of the seed layer as indicated in Fig. 4. Another reason is that the seed layer is relatively thin, which is unable to efficiently avoid the inhibiting effect of the Al3+ (contained beneath the Al2O3 layer) on the growth of the ZnO NS52. The ZnO NS started to exhibit an ordered morphology after the seed layer growth cycle reaches 100. The TEM image of one ZnO NS shown in Fig. S1 in the supporting information exhibit that the as-grown ZnO NS are single crystalline. As the seed layer growth cycle increases from 100 to 200, the obtained ZnO NS exhibit an increase in diameter and length. On the contrary, the density of the ZnO NS is reduced. The increased diameter is owning to the increased grain size of the ZnO crystal in the seed layer. Because the single crystal epitaxial growth of the ZnO NS are most likely to start from the crystal grains inside the seed layer. We speculate that the increased ZnO crystal grain size is achieved by linking the nearby small grains together. Thus, the number of the grains reduces, leading to the reduced density of the ZnO NS. As fewer NS can be grown within a certain area, the growth of each wire-shaped NS is accelerated, leading to the increased length of the NS. Results show that the surface morphology of the ZnO NS can be controlled by altering the thickness of the ALD grown ZnO seed layer.

(a–d) Morphology evolution of the ZnO NS synthesized from the ZnO seed layers indicated in Fig. 4.

To evaluate the light trapping ability, the reflectance spectra of the bare mc-Si, the optimized mc-Si/Al2O3 stack, the mc-Si/Al2O3/ZnO NS stack prepared in Fig. 5a–d are shown in Fig. 6. Significantly, more than 35% of the incident light is reflected away from the bare mc-Si surface. Deposition of the Al2O3 layer only helps a little, the reflectance loss still excess 30%. It is encouraged that the reflectance is largely suppressed after the growth of the ZnO NS. It is not surprising that the ZnO NS synthesized from the 50 cycles grown seed layer show the highest reflection, because the distribution of the ZnO NS is inhomogeneous (indicated in Fig. 5a). As the seed layer growth cycle increases from 100 to 200, the lowest reflectance value of each mc-Si/Al2O3/ZnO NS stack gradually decreases (from 7.6% of 100 cycles seed layer growth to 4.3% of 200 cycles seed layer growth). Meanwhile, the lowest reflectance value point shifts from the short wavelength toward the long wavelength (from 7.6% of 100 cycles seed layer growth to 4.3% of 200 cycles seed layer growth). The reduced lowest reflectance value is owing to the increased length of the NS, which enhances the multiple reflections of the incident light. We speculate that the spectrum shift of the lowest reflectance value point is as a result of the increased thickness of the ZnO seed layer. For single anti-reflection layer, the relationship between the film thickness (d) and the lowest reflectance wavelength can be explained as:

where N is the refractive index of the film, d is the film thickness, θ is the angle of the incident light, m is any natural number. From this equation, it is evident that the increased film thickness will lead to the “red shift” of λ. This trend corresponds with our observations. The calculated solar energy weighted (AM 1.5) reflectance (Rw) of the nanostructured surface with seed layer growth cycle ranges from 100 to 200 are 9.3%, 8.5% and 8.7% respectively. Results show that the seed layer growth cycle of 150 is the optimum value for the fabrication of the solar cells.

Two dimensional (2D) finite difference time domain (FDTD) analysis is carried out to gain insight into the light harvesting mechanism of the optimized mc-Si/Al2O3/ZnO NS stack. The bare mc-Si surface as well as the optimized mc-Si/Al2O3 stack are also added for comparison. In the simulation, the wavelength of the incident light is chosen to be 550 nm, which is close to the peak irradiance in solar spectrum. The dimension of the Al2O3 layer (12 nm thick, n = 1.65 at 550 nm), the ZnO seed layer (30.5 nm, n = 2.05 at 550 nm) are obtained from ellipsometry measurement. The dimension of the ZnO NS (1 μm in length, 60 nm in diameter, 70 nm in period) are averaged from the SEM image show in Fig. 5c. The light intensity distribution (|Ey|) for the three structures mentioned above are shown in Fig. 7a1–c1. The strong |Ey| on both of the mc-Si (Region A1) and the mc-Si/Al2O3 stack (Region B1) indicates a high surface reflectance, confirming with the reflectance results shown in Fig. 6. It is evidently shown in Region C1 that the the intensity of reflected light is greatly reduced after the formation of the ZnO NS. The strong |Ey| distribution at the Region C3 indicating the ZnO NS play a crucial role in suppressing light reflection. One reason is that ZnO has a relatively appropriate refractive index of ~2 in visible light spectrum53. Meanwhile, the NS morphology provides a density-graded interference between the air and the substrate26,54. Moreover, the effective path length of the incident light is prolonged by multiple reflection effect between the NS. These three effects further boost the light trapping ability of the ZnO NS. As shown in Region C3, the bright field inside each ZnO NS reveals that most of the incident light couples into the cylinder-shaped NS. The red field shown in region C3 suggest that another part of the incident light as well as the escaped light from the NS undergo multiple bounces between the nearby NS. At each bounce, more light is coupled into the ZnO NS. Owing to the wide bandgap character of both ZnO and Al2O3, these two materials are highly transparent in visible light spectrum. Thus, the light couples into the ZnO NS are then transmitted to the ZnO seed layer and the beneath Al2O3 layer, eventually absorbed by the mc-Si. Benefited from the excellent anti-reflection ability of the ZnO NS, the |Ey| distribution in region C2 is obviously stronger than that in Region A2 and B2, demonstrating an enhanced light absorption of the mc-Si substrate. Figure 7a2–c2 show the vision image of the mc-Si solar cells based on the three surfaces mentioned above. Comparing with the cells in Fig. 7a2,b2, the cell in Fig. 7c2 is black in color, reconfirming the wide-band photon capturing ability of the ZnO NS in visible light spectrum.

Simulated cross-sectional light intensity |Ey| distribution at 550 nm wavelength on (a1) bare mc-Si surface, (b1) optimized mc-Si/Al2O3 stack, (c1) optimized mc-Si/Al2O3/ZnO NS stack. (a2–c2) photographs of the fabricated mc-Si solar cells based on the bare mc-Si surface, the optimized mc-Si/Al2O3 stack, the optimized mc-Si/Al2O3/ZnO NS stack, respectively.

Photovoltaic Performance

To verify the effectiveness of the optimized mc-Si/Al2O3/ZnO NS stack for photovoltaic applications, the corresponding solar cells are subsequently fabricated. The detected J-V curves are shown in Fig. 8a, the obtained cell parameters are summarized in Table 2. The bare mc-Si solar cell exhibit a poor Voc and Jsc performance, which is related to the high surface recombination rate and consistent with its low τ of ~43 μs shown in Fig. 2. The cell based on the optimized mc-Si/Al2O3 stack exhibit a simultaneous increase in Voc and Jsc, leading to an evidently improved CE. Our previous work indicate that the improvement is as a result of suppressed surface recombination rate on mc-Si by Al2O3 passivation (echo with the τ increment in Region I of Fig. 2). A further increment in Jsc of ~6.1% is observed by the cell based on the optimized mc-Si/Al2O3/ZnO NS stack. The improvement in Jsc is mainly contributed by the significantly lowered surface reflectance on mc-Si/Al2O3 stack after the formation ZnO NS (indicated in Fig. 6), leading to an increase in photon generated carriers. A maximum conversion efficiency of 15.8% is achieved by the optimized mc-Si solar cell with two functional layers. Meanwhile, the Voc performance of the solar cell with mc-Si/Al2O3/ZnO NS and mc-Si/Al2O3/ZnO NS stack are identical. It indicated that the passivation quality of the Al2O3 on Si surface has not degraded very much after the ZnO NS growth, which agrees with the minority carrier lifetimes shown in Fig. 2. Moreover, the cell based on mc-Si/ZnO NS is also fabricated for comparison. Although an improved Jsc of the cell is also observed, the CE is limited by the low Voc value. It can be concluded that the Al2O3 layer and the ZnO NS can compensate for each other in surface passivation and light trapping. Both of them are indispensable for achieving the maximum CE of the mc-Si solar cell in this work.

The external quantum efficiency (EQE) analyzation is performed on the representative cells listed in Table 2. The obtained results are shown in Fig. 8b. Comparing with the solar cell based on bare mc-Si, the Al2O3 passivated cell exhibit an enhanced photon conversion ability in the whole 300–1100 range owning to the suppressed surface recombination rate. After the ZnO NS are further added on the Al2O3 film, the obtained cell exhibit a reduced photon conversion rate in the range of 300–400 nm. This can be explained by the band edge absorption of the ZnO for short wavelength photons. Therefore, less photons in that range can be absorbed by the mc-Si substrate. It is encouraged that the EQE of the cell based on the Al2O3/ZnO NS stack show an evident increase in 450–700 nm range. The increase is owing to the improved anti-reflection ability in the visible spectrum by the application of the ZnO NS. Fortunately, the solar irradiation mainly concentrates in that range55, leading to a net increase in Jsc performance of 1.9 mA/cm2 of the obtained cell. Comparing with the cell with the bare mc-Si surface, the cell based on the mc-Si/ZnO NS also exhibit an improved EQE performance. However, the improvement is limited by the high surface recombination rate owing to the poor passivation quality of the ZnO. Therefore, the cell based on the mc-Si/ZnO NS show lower EQE in high solar energy range (450–700 nm) than the Al2O3 passivated cell, leading to the overall poor Jsc performance shown in Table 2. Results show that if the Al2O3 layer is removed away from the mc-Si/Al2O3/ZnO NS stack, the merit in photon capturing of the ZnO NS will be overwhelmed by the poor passivation quality of the ZnO seed layer on the mc-Si surface.

To further prove the effectiveness of the mc-Si solar cell based on the Al2O3/ZnO NS stack demonstrated in this work, comparisons are made among the a-Si, sc-Si and mc-Si solar cells based on the ZnO NS reported in recent years. The photovoltaic performance of these cells are listed in Table 3. Although the a-Si solar cells developed by Nowak et al.28,29 exhibit relatively low CEs below 10%, the fabrication procedure was simple and cost-effective. For the mc-Si solar cells, the CE of the mc-Si solar cell with ZnO NS anti-reflection surface demonstrated by Chen et al.31 was limited by its relatively low Voc of ~500 mV (typically >610 mV for commercial sc-Si cells). The identical results were also obtained by Aurang et al. in sc-Si solar cell applications33. This was owing to the poor passivation quality of the ZnO on Si surface as mentioned above. In the current work, this problem was settled by adding an Al2O3 interfacial layer between the mc-Si and the ZnO NS as described in Table 2, which is similar to those demonstrated in refs 34 and 35. The ALD-Al2O3 passivation layer have shown several merits over the thermal-SiO234 and the PECVD-SiNx35 films. As compared to the thermal-SiO2, the deposition temperature of the passivation layer can be reduced greatly from 850 °C to 200 °C by utilizing the ALD-Al2O3. Moreover, the Al2O3/ZnO seed layer stacks can be prepared in an ALD chamber. On the other hand, the ALD-Al2O3 layer was pin-hole free. Comparing with the PECVD-SiNx thin film. During the hydro-thermal growth procedure of the ZnO NS, the pin-hole free passivation layer can prevent the reaction solution from reaching the Si/front electrode area more efficiently. This is beneficial for obtaining high quality solar cells with good Voc and FF performance. However, The Jsc of the cell demonstrated in this work was not as high as that of the others. Because there is no surface texturing process on mc-Si in this work. On the positive side, the usage of highly toxic or corrosive chemicals such as HNO3 and HF was avoided, which is very important for realizing the eco-friendly production. Fortunately, the Jsc loss of the cells in this work was largely compensate by a relatively high FF value, which is as a result of improved ohmic contact formation quality of the front electrodes. This is realized by changing the front electrode screening and firing steps prior to the Al2O3 passivation. Eventually, a maximized conversion efficiency of 15.8% is achieved by the multi-crystalline solar cell with the optimized Al2O3/ZnO nanostructures stack, which exhibit comparable performance to the previously reported sc-Si cell based on ZnO nanostructures with highest conversion efficiency of 16.0%34. It is noted that the Al2O3/ZnO NS stack demonstrated in this work offers a potential way for realizing the eco-friendly fabrication of high performance mc-Si solar cells.

Conclusion

In summary, a multi-crystalline solar cell with two functional layers is demonstrated by introducing ZnO nanostructures and an Al2O3 spacer layer. The eco-friendly fabrication is achieved by the low temperature deposition of an Al2O3 and a ZnO seed layer utilizing the atomic-layer-deposition technic. The ZnO nanostructures are prepared by and nontoxic hydro-thermal growth. For passivating the n+ -type multi-crystalline Si, most of the dangling bonds on the multi-crystalline Si surface can be saturated by a 12 nm thick Al2O3 film. Meanwhile, the adverse impact of the negative charge concentration inside the Al2O3 film is minimized. The imperfectness of the Al2O3 layer in anti-reflection is conquered by a further growth of ZnO nanostructures. Results show that the ZnO nanostructures synthesized from the seed layer with optimized thickness exhibit excellent photon harvesting ability in the visible light range, leading to an evident increase in short circuit current of the solar cells. Eventually, a maximized conversion efficiency of 15.8% is achieved by the multi-crystalline solar cell with the optimized Al2O3/ZnO nanostructures stack, which exhibit comparable performance to the previously reported single-crystalline Si cell based on ZnO nanostructures with highest conversion efficiency of 16.0%. Consequently, the proposed hierarchical nano structure in this work pave a facile way for realizing the eco-friendly fabrication and potential application of the high performance silicon solar cells in the future.

Methods

Preparation of the Al2O3/ZnO NS stack

The Al2O3 passivation layer and the ZnO seed layer were deposited by thermal ALD (Beneq TFS-200) at 200 °C. For the Al2O3 growth, the precursors were trimethylaluminium (TMA) and H2O. Then, the as-deposited Al2O3 films were annealed under a N2 environment at 425 °C in a rapid thermal annealing (RTA) furnace (Annealsys AS-ONE). After that, the ZnO seed layer was deposited, utilizing diethylzinc (DEZ) and H2O as the precursors. Finally, the ZnO NS were grown by hydro-thermal method at 80 °C. The utilized reactors were zinc nitrate and hexamethylene HMT, with equal concentration of 25 mM. The growth duration was 8 hours.

Fabrication of the solar cell

Commercial grade p-type mc-Si wafers with a resistivity of 1–3 Ω∙cm were used as the starting substrate. At first, the wafers are immersed in 20 wt. %, 80 °C NaOH solution for 5 min for removing saw damages. Then, an n+ emitter with a sheet resistance of 70 Ω per square was formed using liquid POCl3 diffusion. The formed phosphor silicon glass was removed by immersing the wafers in diluted HF solution. After that, the front/back electrode was formed by screen- printing of silver/aluminum paste. The area-fraction on the surface was ~9% (the power loss induced by grid shadow was not excluded in the Jsc and CE calculation), the active area of each cell was 3.24 cm2. The front/rear electrode metallization were realized by annealing the samples in the RTA furnace in air with an peak temperature of ~720 °C. The samples were then shortly immersed into diluted HF to remove the oxide layer and contaminant formed on the front surface of the samples during the formation/annealing step of the electrodes. Then, the Al2O3/ZnO NS stack were prepared on the front surface of the cells.

Sample characterization

The minority carrier lifetime on the mc-Si surface was obtained using a life time tester (Semilab WT-1000). The C-V curves were measured by a semiconductor device analyzer (Agilent B1500A). The XRD measurement was carried out in Bruker D8 system. The surface morphologies were characterized by a SEM (Hitachi SU1510). The reflectance spectra were measured using a spectrometer (Shimadzu UV3600) equipped with an integrating sphere. The solar cell performance was obtained under a standard 1-sun illumination with a sun simulator (Oriel-940401A) and a sourcemeter (Keithley-2400). The data obtained was based on an average of about 6 wafers/cells.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Chen, H.-Y. et al. Realizing a facile and environmental-friendly fabrication of high-performance multi-crystalline silicon solar cells by employing ZnO nanostructures and an Al2O3 passivation layer. Sci. Rep. 6, 38486; doi: 10.1038/srep38486 (2016).

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

Sarti, D. & Einhaus, R. Silicon feedstock for the multi-crystalline photovoltaic industry. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 72, 27–40 (2002).

Pizzini, S. Bulk solar grade silicon: how chemistry and physics play to get a benevolent microstructured material. Appl. Phys. A: Mater. Sci. Process. 96, 171–188 (2009).

Ye, X. et al. 18.45%-Efficient Multi-Crystalline Silicon Solar Cells with Novel Nanoscale Pseudo-Pyramid Texture. Adv. Funct. Mater. 24, 6708–6716 (2014).

Lee, E. et al. Improved LDSE processing for the avoidance of overplating yielding 19.2% efficiency on commercial grade crystalline Si solar cell. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 95, 3592–3595 (2011).

Park, K. M., Lee, M. B., Shin, J. W. & Choi, S. Y. Investigation of surface features using reactive ion etching method for the enhanced performance of multi-crystalline silicon solar cells. Sol. Energy 91, 37–47 (2013).

Zhong, S. et al. Influence of the texturing structure on the properties of black silicon solar cell. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 108, 200–204 (2013).

Yue, Z. et al. Large-scale black multi-crystalline silicon solar cell with conversion efficiency over 18%. Appl. Phys. A: Mater. Sci. Process. 116, 683–688 (2014).

Oh, J., Yuan, H. C. & Branz, H. M. An 18.2%-efficient black-silicon solar cell achieved through control of carrier recombination in nanostructures. Nat. Nanotechnol. 7, 743–748 (2012).

Morikawa, H., Niinobe, D., Nishimura, K., Matsuno, S. & Arimoto, S. Processes for over 18.5% high-efficiency multi-crystalline silicon solar cell. Curr. Appl. Phys. 10, S210–S214 (2010).

Niinobe, D. et al. Large-size multi-crystalline silicon solar cells with honeycomb textured surface and point-contacted rear toward industrial production. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 95, 49–52 (2011).

Inomata, Y., Fukui, K. & Shirasawa, K. Surface texturing of large area multicrystalline silicon solar cells using reactive ion etching method. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 48, 237–242 (1997).

Schultz, O., Glunz, S. W. & Willeke, G. P. Multicrystalline silicon solar cells exceeding 20% efficiency. Prog. Photovolt: Res. Appl. 12, 553–558 (2004).

Park, K. M., Lee, M. B. & Choi, S. Y. Investigation of surface features for 17.2% efficiency multi-crystalline silicon solar cells. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 132, 356–362 (2015).

Chen, W. H., Lin, H. H. & Hong, F. C. N. Improvement of conversion efficiency of multi-crystalline silicon solar cells using reactive ion etching with surface pre-etching. Thin Solid Films 597, 50–56 (2015).

Dai, Y. A. et al. Subwavelength Si nanowire arrays for self-cleaning antireflection coatings. J. Mater. Chem. 20, 10924–10930 (2010).

Lin, X. X., Hua, X., Huang, Z. G. & Shen, W. Z. Realization of high performance silicon nanowire based solar cells with large size. Nanotechnology 24, 235402 (2013).

Chen, H. Y. et al. Enhanced photovoltaic performance of inverted pyramid-based nanostructured black-silicon solar cells passivated by an atomic-layer-deposited Al2O3 layer. Nanoscale 7, 15142–15148 (2015).

Srivastava, S. K. et al. Antireflective ultra-fast nano scale texturing for efficient multi-crystalline silicon solar cells. Sol. Energy 115, 656–666 (2015).

Liu, Y. et al. Nanostructure Formation and Passivation of Large-Area Black Silicon for Solar Cell Applications. Small 8, 1392–1397 (2012).

Yu, M., Long, Y. Z., Sun, B. & Fan, Z. Recent advances in solar cells based on one-dimensional nanostructure arrays. Nanoscale 4, 2783–2796 (2012).

Qi, D. et al. Bio-inspired antireflective hetero-nanojunctions with enhanced photoactivity. Nanoscale 5, 12383–12387 (2013).

Leung, S. F. et al. Light Management with Nanostructures for Optoelectronic Devices. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 5, 1479–1495 (2014).

Choudhury, B. D., Abedin, A., Dev, A., Sanatinia, R. & Anand, S. Silicon micro-structure and ZnO nanowire hierarchical assortments for light management. Opt. Mater. Express 3, 1039–1048 (2013).

Cai, J. & Qi, L. Recent advances in antireflective surfaces based on nanostructure arrays. Mater. Horiz. 2, 37–53 (2015).

Greene, L. E. et al. General route to vertical ZnO nanowire arrays using textured ZnO seeds. Nano Lett. 5, 1231–1236 (2005).

Lee, Y. J., Ruby, D. S., Peters, D. W., McKenzie, B. B. & Hsu, J. W. P. ZnO nanostructures as efficient antireflection layers in solar cells. Nano Lett. 8, 1501–1505 (2008).

Soleimanzadeh, R. et al. Sequential microwave-assisted ultra-fast ZnO nanorod growth on optimized sol-gelseedlayers. J. Cryst. Growth 426, 228–233 (2015).

Nowak, R. E., Vehse, M., Sergeev, O., von Maydell, K. & Agert, C. ZnO nanorod arrays as light trapping structures in amorphous silicon thin-film solar cells. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 125, 305–309 (2014).

Nowak, R. E. et al. ZnO Nanorods with Broadband Antireflective Properties for Improved Light Management in Silicon Thin-Film Solar Cells. Adv. Opt. Mater. 2, 94–99 (2014).

Geissendoerfer, S. et al. Integration of n-doped ZnO nanorod structures as novel light-trapping concept in amorphous thin film silicon solar cells. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 111, 153–159 (2013).

Chen, J. Y. & Sun, K. W. Growth of vertically aligned ZnO nanorod arrays as antireflection layer on silicon solar cells. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 94, 930–934 (2010).

Wang, W. C. et al. Efficiency Enhancement and Anti-Corrosion Protection on Silicon Solar Cells by Atomic-Layer-Deposited Al2O3 Conformal Shell Layer on Antireflective ZnO Nanorod Array. ECS J. Solid State Sci. Technol. 3, Q221–Q226 (2014).

Aurang, P., Demircioglu, O., Es, F., Turan, R. & Unalan, H. E. ZnO Nanorods as Antireflective Coatings for Industrial-Scale Single-Crystalline Silicon Solar Cells. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 96, 1253–1257 (2013).

Liu, Y. et al. Hybridizing ZnO Nanowires with Micropyramid Silicon Wafers as Superhydrophobic High-Efficiency Solar Cells. Adv. Energy Mater. 2, 47–51 (2012).

Lin, C. A., Lai, K. Y., Lien, W. C. & He, J. H. An efficient broadband and omnidirectional light-harvesting scheme employing a hierarchical structure based on a ZnO nanorod/Si3N4-coated Si microgroove on 5-inch single crystalline Si solar cells. Nanoscale 4, 6520–6526 (2012).

Yeh, L. K. et al. Giant Efficiency Enhancement of GaAs Solar Cells with Graded Antireflection Layers Based on Syringelike ZnO Nanorod Arrays. Adv. Energy Mater. 1, 506–510 (2011).

Pietruszka, R. et al. New efficient solar cell structures based on zinc oxide nanorods. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 143, 99–104 (2015).

Groner, M. D., Fabreguette, F. H., Elam, J. W. & George, S. M. Low-temperature Al2O3 atomic layer deposition. Chem. Mater. 16, 639–645 (2004).

George, S. M. Atomic Layer Deposition: An Overview. Chem. Rev. 110, 111–131 (2010).

Agostinelli, G. et al. Very low surface recombination velocities on p-type silicon wafers passivated with a dielectric with fixed negative charge. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 90, 3438–3443 (2006).

Hoex, B., Heil, S. B. S., Langereis, E., van de Sanden, M. C. M. & Kessels, W. M. M. Ultralow surface recombination of c-Si substrates passivated by plasma-assisted atomic layer deposited Al2O3 . Appl. Phys. Lett. 89, 042112 (2006).

Schmidt, J. et al. Surface passivation of high-efficiency silicon solar cells by atomic-layer-deposited Al2O3 . Prog. Photovoltaics: Res. Appl. 16, 461–466 (2008).

Benick, J. et al. High efficiency n-type Si solar cells on Al2O3-passivated boron emitters. Appl. Phys. Lett. 92, 253504 (2008).

Hoex, B., Schmidt, J., Pohl, P., van de Sanden, M. C. M. & Kessels, W. M. M. Silicon surface passivation by atomic layer deposited Al2O3 . J. Appl. Phys. 104, 044903 (2008).

Lei, D. et al. Modulation of atomic-layer-deposited Al2O3 film passivation of silicon surface by rapid thermal processing. Appl. Phys. Lett. 99, 052103 (2011).

Otto, M. et al. Extremely low surface recombination velocities in black silicon passivated by atomic layer deposition. Appl. Phys. Lett. 100, 191603 (2012).

Hoex, B., van de Sanden, M. C. M., Schmidt, J., Brendel, R. & Kessels, W. M. M. Surface passivation of phosphorus-diffused n+ -type emitters by plasma-assisted atomic-layer deposited Al2O3 . Phys. Status Solidi RRL 6, 4–6 (2012).

Richter, A., Benick, J., Kimmerle, A., Hermle, M. & Glunz, S. W. Passivation of phosphorus diffused silicon surfaces with Al2O3: Influence of surface doping concentration and thermal activation treatments. J. Appl. Phys. 116, 243501 (2014).

Naumann, V., Otto, M., Wehrspohn, R. B. & Hagendorf, C. Chemical and structural study of electrically passivating Al2O3/Si interfaces prepared by atomic layer deposition. J. Vac. Sci. Technol., A 30, 04D106 (2012).

Dingemans, G., Einsele, F., Beyer, W., van de Sanden, M. C. M. & Kessels, W. M. M. Influence of annealing and Al2O3 properties on the hydrogen-induced passivation of the Si/SiO2 interface. J. Appl. Phys. 111, 093713 (2012).

Gu, Y. Z. et al. Effects of ZnO seed layer annealing temperature on the properties of n-ZnO NWs/Al2O3/p-Si heterojunction. Opt. Express 23, 24456–24463 (2015).

Liu, J. et al. One-step hydrothermal synthesis and optical properties of aluminium doped ZnO hexagonal nanoplates on a zinc substrate. Crystengcomm 13, 1283–1286 (2011).

Yoshikawa, H. & Adachi, S. Optical constants of ZnO. Jpn. J. Appl. Phys. 36, 6237–6243 (1997).

Branz, H. M. et al. Nanostructured black silicon and the optical reflectance of graded-density surfaces. Appl. Phys. Lett. 94, 231121 (2009).

Polman, A., Knight, M., Garnett, E. C., Ehrler, B. & Sinke, W. C. Photovoltaic materials: Present efficiencies and future challenges. Science 352, aad4424 (2016).

Acknowledgements

This work is supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 51102048, 61376008, 61376119), SRFDP (No. 20110071120017), the Science Foundation of State Key Lab of Silicon Materials (Grant no. SKL2015-01), and the Innovation Program of Shanghai Municipal Education Commission (14ZZ004).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

H.Y.C. fabricated the samples and performed the measurements. H.Y.C., L.S. and Q.H.R. analyzed the data with H.L.L. and wrote the manuscript. L.S. and Y.Z. conceived and supervised the experiments. H.Z., X.M.J., W.J.L., S.J.D. and X.F.Y. participated in drafting the manuscript. D.W.Z. was involved in planning of study and headed the project. All authors discussed the results and commented on the manuscript.

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Chen, HY., Lu, HL., Sun, L. et al. Realizing a facile and environmental-friendly fabrication of high-performance multi-crystalline silicon solar cells by employing ZnO nanostructures and an Al2O3 passivation layer. Sci Rep 6, 38486 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep38486

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/srep38486

This article is cited by

-

An n-ZnO/i-MoS2/p-Si heterojunction solar cell with an enhanced photoswitching response

Journal of Computational Electronics (2021)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.