Abstract

Clinicopathological features and prognosis of omental GISTs are limited due to the extremely rare incidence. Therefore, the aim of the present study was to investigate the clinicopathological features and prognosis of omental GISTs. Omental GISTs cases were obtained from our center and from case reports and clinical studies extracted from MEDLINE. Clinicopathological features and survivals were analyzed. A total of 99 cases of omental GISTs were enrolled in the present study. Omental GISTs occurred predominantly in greater omentum (78/99, 78.8%). The majority of tumors exceeded 10 cm in diameter (67/98, 68.3%) and were high risk (88/96, 91.7%). Histological type was correlated with tumor location and mutational status. The five year DFS and DSS was 86.3% and 80.6%, respectively. Mitotic index was risk factor for prognosis of omental GISTs. Prognosis of omental GISTs was worse than that of gastric GISTs by Kaplan-Meier analysis. However, multivariate analysis showed that the prognosis was comparable between the two groups. The majority of omental GISTs were large and high risk. Mitotic index was risk factor for prognosis of omental GISTs. The prognosis was comparable between omental and gastric GISTs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GISTs) are the most common mesenchymal tumor of the gastrointestinal tract1. GISTs are believed to originate from the interstitial cells of Cajal, the pacemaker cells of gastrointestinal tract2. GISTs can occur anywhere throughout the gastrointestinal tract. The most common locations are the stomach (40 to 70%), followed by small intestine (20 to 40%) and colorectum (5 to 15%)3. GISTs that arise outside the gastrointestinal tract as primary tumor are designated as extra-gastrointestinal stromal tumors (EGISTs). The EGISTs are located in the omentum, mesentery, liver, pancreas and retroperitoneum, etc4.

Studies involving large numbers of omental GISTs are extremely rare. To date, there was only one study contained a relatively large cases of omental GISTs5. Thus, various questions remain unanswered with respect to the clinicopathological features and prognosis. Therefore, the aim of the present study was to investigate the clinicopathological features and prognosis of omental GISTs.

Results

The clinicopathological features were summarized in Table 1. There were 55 male (59.1%) and 38 female (40.9%). The patient age ranged from 22–99 years (median, 60 years; mean, 59.2 years). The most common symptom was abdominal pain (25/51, 49.0%), followed by abdominal mass (10/51, 19.6%) and abdominal distension (8/51, 15.7%). Twenty-one tumors located in the lesser omentum (21.2%), 78 tumors located in the greater omentum (78.8%). Eighty-six patients underwent complete surgical resection (86/95, 90.5%), 4 patients underwent palliative surgical resection (4/95, 4.2%) and 5 patients did not receive surgical resection (5/95, 5.3%).

The tumors ranged from 0.7 to 40 cm in maximum diameter (median, 13.0 cm; mean, 14.1 cm). Forty-two patients displayed spindle cell morphology (42/87, 48.3%), 29 patients displayed epithelioid morphology (29/87, 33.3%) and 16 patients displayed mixed morphology (16/87, 18.4%). The mitotic index of 32 patients exceeded 5/50 HPF (32/85, 37.6%). CD117 positivity was detected in 49 patients (49/58, 84.5%), CD34 positivity was detected in 36 patients (36/43, 83.7%) and DOG-1 positivity was detected in 8 patients (8/9, 88.9%). Twenty-seven patients were analyzed for gene mutation status. Nine patients carried KIT mutation (9/27, 33.3%), 14 patients carried PDGFRA mutation (14/27, 51.9%), the remaining 5 patients were wild type (5/27, 18.5%). According to NIH risk classification, 2 patients were very low risk (2/96, 2.1%), 5 patients were low risk (5/96, 5.2%), 1 patient was intermediate risk (1/96, 1.0%) and 88 patients were high risk (88/96, 91.7%). Information of adjuvant imatinib therapy were recorded in 58 patients and 15 patients (25.9%) received imatinib therapy.

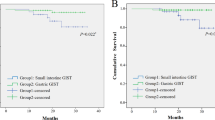

Survival data of omental GISTs were summarized in Table 1. Survival data of 63 patients were eventually selected for analysis using exclusion criteria described in the materials and methods. The follow up time ranged from 2 to 134 months (mean, 36.6 months; median, 21.1 months). Seven patients showed recurrence or metastasis, 6 patients suffered from GIST related deaths. The 1-, 3- and 5-year DFS was 90.8%, 86.3% and 86.3%, respectively. The 1-, 3- and 5-year DSS was 100.0%, 87.9% and 80.6%, respectively. The DFS and DSS of omental GISTs were analyzed using Kaplan-Meier survival analyses and shown in Fig. 1.

The relationship between clinicopathological features were analyzed (data not shown). The histological type was correlated with tumor location and mutational status. The ratio of epithelioid and mixed morphology of greater omental GISTs were significantly higher than that of lesser omental GISTs (P = 0.036). The epithelioid and mixed morphology were significantly correlated with PDGFRA mutation (P < 0.001).

Prognostic factors for DFS and DSS of omental GISTs according to univariate analysis were shown in Table 2. The results showed that the tumor size and mitotic index were risk factors for DFS of omental GISTs and mitotic index was the only risk factor for DSS of omental GISTs. The DFS and DSS of omental GISTs according to tumor size and mitotic index were shown in Figs 2 and 3.

The clinicopathological features of 99 omental GISTs including age, gender, tumor size, histological type, mitotic index and NIH risk category were compared with 297 gastric GISTs in our institution (Table 3). The results showed that the distribution of tumor size, histological type and NIH risk category were significantly different between omental and gastric GISTs (all with P < 0.001).

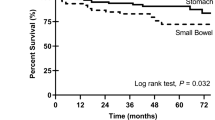

In order to compare the prognosis of omental GISTs with gastric GISTs, survivals of 63 cases of omental GISTs and 217 cases of gastric GISTs with follow up data were analyzed. The results showed that the DFS and DSS of omental GISTs were significantly worse than that of gastric GISTs (Fig. 4). Further, multivariate analysis was performed to evaluate the prognostic value of locations (Table 4). The results showed that location was not an independent risk factor for prognosis of omental and gastric GISTs.

Discussion

Clinicopathological features and prognosis of omental GISTs are limited due to the extremely rare incidence. Therefore, the aim of the present study was to investigate the clinicopathological features and prognosis of omental GISTs from our center and from literatures in MEDLINE. The present study represents the largest analysis of omental GISTs and indicates some features significantly associated with omental GISTs.

To date, the largest cases of omental GISTs was reported by Miettinen et al.5. The study contained 95 cases. However, it mainly focused on clinicopathological features of omental GISTs. The distribution of age, gender, tumor size and mitotic index were similar to our present study. However, a few highlights with respect to clinicopathological features were revealed and the prognosis of omental GISTs were analyzed in depth in our present study.

The precise etiology of omental GISTs remains to be clarified. In the study reported by Miettinen et al.5, over half of the solitary omental GISTs were attached to or involved the gastrointestinal tract and the histologic features were similar to gastric or small intestinal GISTs. Thus, they believed that solitary omental GISTs are actually externally extending gastric or small intestinal GISTs and many others may have lost their original connection to the stomach or small intestine and become parasitically attached into the omentum. For multiple omental GISTs, they were believed to be metastatic tumors from an overlooked primary tumor.

However, it has been reported that GISTs in the omentum are derived from mesenchymal cells that are less differentiated than ICCs6. These may be ICC precursors straying into the abdominal cavity7. Moreover, Sakurai et al. found that KIT positive bipolar cells were present just beneath the mesothelial cells of the omentum. Thus, the identification of an ICC-counterpart in the omentum is the evidence that omental GISTs may also originate from ICC. They also demonstrated the existence of ICC-like cells focally in the omentum at 21 weeks of human gestation8. However, it is unknown whether they develop in situ or migrate from the ICC of the tubular GI tract at particular point in fetal development. Dedemadi et al. reported that there is no difference in the incidence between lesser and greater omentum9. However, the incidence of GISTs in the greater omentum was approximately four times as much as that of lesser omentum in our present study. The difference in the incidence between lesser and greater omentum needs further investigation.

In our present study, the majority of omental GISTs exceeded 10 cm in diameter and approximately ninety percent of the tumors were classified as high risk category. The spectrum of tumor size and NIH risk category of omental GISTs were significantly different from that of gastric GISTs in our institution. This may attribute to the absence of specific symptoms when the tumor was not large enough in the omentum or tumors did not invade adjacent gastrointestinal tract. Once the GISTs of the omentum reached a significant size, symptoms will appears including abdominal pain, mass, distension, fatigue and discomfort. Thus, early diagnosis of omental GISTs is very difficult.

Histologically, most GISTs display spindle cell morphology (70%), whereas a minority is of epithelioid (20%) or mixed phenotypes (10%)10. However, in the study reported by Miettinen et al.5, 53 out of 89 tumors showed spindle cell morphology (59.6%), 28 tumors were epithelioid (31.5%) and 8 tumors were mixed (8.9%). In our present study, 29 tumors displayed epithelioid morphology (33.3%) and 16 tumors displayed mixed morphology (18.4%). The proportion of epithelioid and mixed morphology of omental GISTs were significantly higher than that of gastric GISTs in our center and previous report. This indicated that the constituent ratio of epithelioid and mixed morphology could be various from each other depending on the location of GISTs. Further, we found that the incidence of epithelioid and mixed cell morphology was higher in greater omental GISTs than in lesser omental tumors. This may indicate that the origins of tumors in lesser omentum and greater omentum were different from each other, which needed further investigation.

In 1998, Hirota et al. reported their groundbreaking discovery of KIT mutations in GISTs. It is now established that 70% to 80% of GISTs harbor a KIT gene mutation11 and PDGFRA mutations occur in approximately 8% to 10% of gastric GISTs12. In the study reported by Miettinen et al.5, KIT mutation was detected in 15/36 tumors (41.7%) and PDGFRA mutation was detected in 11/36 tumors (30.6%). However, in our present study, only 9/27 tumors (33.3%) harbored KIT mutation but 14/27 tumors (51.9%) harbored PDGFRA mutation. Although the incidence of PDGFRA mutation in Miettinen’s and our report were higher than previous report, the results in our present study was even higher than that in Miettinen’s report. It was reported that spindle cell morphology correlates with KIT mutations13 and epithelioid and mixed cell morphology correlates with PDGFRA mutations14. This has also been demonstrated in our present study, the KIT mutations almost exclusively occurred in spindle cell morphology and PDGFRA mutations almost exclusively occurred in epithelioid cell morphology. This indicated that KIT and PDGFRA mutant GISTs probably represent two distinct clinicopathological and molecular genetic disease entities. However, this needs further investigations in depth. It must be pointed out that the data of mutational analysis is only available in too few cases (27/99, 27.3%) in our present study, which are extremely too low to characterize the mutation spectrum of omental GISTs. The limited data could also result in bias during analyzing the association between cell morphology and mutational status. This was one limitation in our present study.

Besides tumor size and mitotic index, tumor location is also one important risk factor for the prognosis of GISTs15 and it was considered that extra-gastrointestinal stromal tumors were more aggressive than gastric GISTs in clinical course. However, the modified NIH risk classification system distinguishes only gastric from non-gastric GISTs and the prognosis of omental GISTs are not discussed. Thus, we compared the prognosis of omental GISTs with gastric GISTs in our center. We found that the prognosis of omental GISTs was significantly worse than that of gastric GISTs. However, multivariate analysis showed that the prognosis was comparable between omental and gastric GISTs. This indicated that the prognosis of omental GISTs was as considerable as gastric GISTs. The significantly lower survival of omental GISTs than gastric GISTs in Kaplan-Meier survival analysis may attribute to the larger tumor size and higher NIH risk category of omental GISTs compared with gastric GISTs. However, it was inevitable that the extremely low incidence of imatinib therapy in our present study would result in bias during analysis of prognosis of omental GISTs. Thus, the actual disease free survival and disease specific survival of omental GISTs may be more favorable than that in our present study.

There are a few limitations in our present study. Firstly, the present study is a retrospective analysis and the completeness of data is limited. This will influence the analysis of clinicopathological features and prognosis. Secondly, the sample size of omental GISTs was not large enough, which will result in statistical bias. Thirdly, due to the limited sample size of duodenal and small intestinal GISTs in our center, the prognosis of omental GISTs were only compared to that of gastric GISTs.

Conclusions

The majority of omental GISTs occurred in greater omentum, exceeded 10 cm in diameter and were high risk. The incidence of epithelioid cell morphology and PDGFRA mutation were relatively high in omental GISTs. The histological type was correlated with location and mutational status. Mitotic index was risk factor for prognosis of omental GISTs. Omental GISTs differ significantly from gastric GISTs in respect to clinicopathologic features. The prognosis was comparable between omental and gastric GISTs.

Methods

GISTs cases of the omentum were from our institution and in addition from the literature. From May 2010 to March 2015, 2 cases of omental GISTs were diagnosed and treated in our institution. Literature search of MEDLINE was performed for all articles in English published from 1998 through 2015. MEDLINE search resulted in 47 case reports8,9,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60 including 57 patients and 6 case series61,62,63,64,65,66 including 40 cases. As a result, a total of 99 omental GISTs patients were identified. In addition, the clinicopathological features and prognosis of 297 cases of gastric GISTs were compared with omental GISTs. This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Xijing Hospital according to the provisions of the Declaration of Helsinki in 1995 (as revised in Edinburgh 2000)67 and written informed consent was obtained from the two patients in our center.

Data including age, gender, accompanied tumor, symptoms, location, tumor size, surgical intervention, histological type, immunohistochemical features, mutational status, mitotic index, NIH risk category, adjuvant therapy, tumor progression and survival data were recorded. The tumors were categorized into very low, low, intermediate and high risk groups according to the modified NIH risk classification criteria reported by Joensuu et al.68. For survival analysis, the inclusion criteria were listed as follows: 1. R0 resection, 2. without distant metastasis, 3. without GIST in other locations, 4. without other malignant tumors, 5. without neoadjuvant imatinib therapy, 6. with follow up data. Due to data acquisition, completeness of data is limited.

Data were processed using SPSS 22.0 for Windows (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Discrete variables were analyzed using the Chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test. Numerical variables were expressed as the mean ± SD unless. Significant predictors for survival identified by univariate analysis were further assessed by multivariate analysis. Evaluation of disease-free-survival (DFS) and disease-specific-survival (DSS) were obtained by the Kaplan-Meier method. The P values were considered to be statistically significant at the 5% level.

Ethical approval and informed consent. This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Xijing Hospital and written informed consent was obtained from the two patients in our center.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Feng, F. et al. Clinicopathological features and prognosis of omental gastrointestinal stromal tumor: evaluation of a pooled case series. Sci. Rep. 6, 30748; doi: 10.1038/srep30748 (2016).

References

Yang, J. et al. Surgical resection should be taken into consideration for the treatment of small gastric gastrointestinal stromal tumors. World J. Surg. Oncol. 11, 273 (2013).

Feng, F. et al. Comparison of Endoscopic and Open Resection for Small Gastric Gastrointestinal Stromal Tumor. Transl. Oncol. 8, 504–508 (2015).

Feng, F. et al. Clinicopathologic Features and Clinical Outcomes of Esophageal Gastrointestinal Stromal Tumor: Evaluation of a Pooled Case Series. Medicine (Baltimore) 95, e2446 (2016).

Joensuu, H. et al. Risk of recurrence of gastrointestinal stromal tumour after surgery: an analysis of pooled population-based cohorts. Lancet Oncol. 13, 265–274 (2012).

Miettinen, M., Sobin, L. H. & Lasota, J. Gastrointestinal stromal tumors presenting as omental masses–a clinicopathologic analysis of 95 cases. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 33, 1267–1275 (2009).

Miettinen, M. & Lasota, J. Gastrointestinal stromal tumors: review on morphology, molecular pathology, prognosis and differential diagnosis. Arch. Pathol. Lab. Med. 130, 1466–1478 (2006).

Kindblom, L. G., Remotti, H. E., Aldenborg, F. & Meis-Kindblom, J. M. Gastrointestinal pacemaker cell tumor (GIPACT): gastrointestinal stromal tumors show phenotypic characteristics of the interstitial cells of Cajal. Am. J. Pathol. 152, 1259–1269 (1998).

Sakurai, S. et al. Gastrointestinal stromal tumors and KIT-positive mesenchymal cells in the omentum. Pathol. Int. 51, 524–531 (2001).

Dedemadi, G. et al. Extragastrointestinal stromal tumors of the omentum: review apropos of a case with a novel gain-of-function KIT mutation. J Gastrointest Cancer 40, 73–78 (2009).

Agaimy, A., Wang, L. M., Eck, M., Haller, F. & Chetty, R. Loss of DOG-1 expression associated with shift from spindled to epithelioid morphology in gastric gastrointestinal stromal tumors with KIT and platelet-derived growth factor receptor alpha mutations. Ann. Diagn. Pathol. 17, 187–191 (2013).

Corless, C. L., Barnett, C. M. & Heinrich, M. C. Gastrointestinal stromal tumours: origin and molecular oncology. Nat. Rev. Cancer 11, 865–878 (2011).

Heinrich, M. C. et al. PDGFRA activating mutations in gastrointestinal stromal tumors. Science 299, 708–710 (2003).

Miettinen, M. & Lasota, J. Gastrointestinal stromal tumors: pathology and prognosis at different sites. Semin. Diagn. Pathol. 23, 70–83 (2006).

Wardelmann, E. et al. Association of platelet-derived growth factor receptor alpha mutations with gastric primary site and epithelioid or mixed cell morphology in gastrointestinal stromal tumors. J. Mol. Diagn. 6, 197–204 (2004).

Rutkowski, P. et al. Risk criteria and prognostic factors for predicting recurrences after resection of primary gastrointestinal stromal tumor. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 14, 2018–2027 (2007).

Tarchouli, M. et al. Extra-Gastrointestinal Stromal Tumor of the Greater Omentum: Unusual Case Report. J Gastrointest Cancer (2015).

Trombatore, C. et al. Extragastrointestinal stromal tumor of lesser omentum: a challenging radiological and histological diagnosis. Clin Imaging 39, 1123–1127 (2015).

Seow-En, I., Seow-Choen, F., Lim, T. K. & Leow, W. Q. Primary omental gastrointestinal stromal tumour (GIST) presenting with a large abdominal mass and spontaneous haemoperitoneum. BMJ Case Rep 2014 (2014).

Amendolara, M. et al. Rare cases reports of gastrointestinal stromal tumour (GIST). G Chir 35, 129–133 (2014).

Kang, J., Jeon, T. J., Yoon, S. O., Lee, K. Y. & Sohn, S. K. An extragastrointestinal stromal tumor in the omentum with peritoneal seeding mimicking an appendiceal mucinous cancer with carcinomatosis. Ann Coloproctol 30, 93–96 (2014).

Iqbal, A., Veerankutty, F. H., Sulfekar, M. S. & Culas, T. B., Multicentric Jejunal and Omental GIST with an Unusual Clinical Presentation-A Case Report. Indian J Surg Oncol 5, 78–80 (2014).

Skandalos, I. K., Hotzoglou, N. F., Matsi, K., Pitta, X. A. & Kamas, A. I., Giant extra gastrointestinal stromal tumor of lesser omentum obscuring the diagnosis of a choloperitoneum. Int J Surg Case Rep 4, 818–821 (2013).

Patnayak, R. et al. Primary extragastrointestinal stromal tumors: a clinicopathological and immunohistochemical study - a tertiary care center experience. Indian J. Cancer 50, 41–45 (2013).

Divakaran, J. & Chander, B. Primary extra-gastrointestinal stromal tumor of the omentum. J. Cancer Res. Ther. 8, 433–435 (2012).

Fagkrezos, D. et al. Extra-gastrointestinal stromal tumor of the omentum: a rare case report and review of the literature. Rare Tumors 4, e44 (2012).

Ogawa, H. et al. A Case of KIT-Negative Extra-Gastrointestinal Stromal Tumor of the Lesser Omentum. Case Rep Gastroenterol 6, 375–380 (2012).

Murayama, Y. et al. Greater omentum gastrointestinal stromal tumor with PDGFRA-mutation and hemoperitoneum. World J Gastrointest Oncol 4, 119–124 (2012).

Gowrishankar, S. Epithelioid omental extra-gastrointestinal stromal tumor: report of a case. Indian J Pathol Microbiol 54, 618–619 (2011).

Medeiros, F. et al. KIT-negative gastrointestinal stromal tumors: proof of concept and therapeutic implications. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 28, 889–894 (2004).

Mouaqit, O. et al. Primary omental gastrointestinal stromal tumors. Clin Res Hepatol Gastroenterol 35, 590–593 (2011).

Jindal, G., Rastogi, R., Kachhawa, S. & Meena, G. L. CT findings of primary extra-intestinal gastrointestinal stromal tumor of greater omentum with extensive peritoneal and bilateral ovarian metastases. Indian J. Cancer 48, 135–137 (2011).

Minegishi, S., Shigemasa, T., Kobayashi, S. & Kasuya, F. A case of a primary gastrointestinal stromal tumor (GIST) found in the greater omentum of a 99-year-old woman. Nihon Ronen Igakkai Zasshi 46, 179–183 (2009).

Aihara, R. et al. Gastrointestinal stromal tumor of the lesser omentum in a young adult patient with a history of hepatoblastoma: report of a case. Surg. Today 39, 349–352 (2009).

Terada, T. Primary multiple extragastrointestinal stromal tumors of the omentum with different mutations of c-kit gene. World J Gastroenterol 14, 7256–7259 (2008).

Liu, H., Li, W. & Zhu, S. Clinical images. Extragastrointestinal stromal tumor of lesser omentum mimicking a liver tumor. Am. J. Surg. 197, e7–e8 (2009).

Felekouras, E. et al. Coexistence of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) and c-Kit negative gastrointestinal stromal tumor (GIST): a case report. South. Med. J. 101, 948–951 (2008).

Llenas-Garcia, J. et al. Primary extragastrointestinal stromal tumors in the omentum and mesentery: a clinicopathological and immunohistochemical study. Hepatogastroenterology 55, 1002–1005 (2008).

Kobayashi, Y. et al. Positron emission tomography image on evaluating intraperitoneal dissemination of malignant gastrointestinal stromal tumor. Hepatogastroenterology 55, 895–897 (2008).

Yoshimura, N. et al. A case of gastrointestinal stromal tumor with spontaneous rupture in the greater omentum. Int Semin Surg Oncol 5, 19 (2008).

Ouazzani, A. et al. Electronic clinical challenges and images in GI. Cystic GIST of the lesser omentum. Gastroenterology 134, e1–e2 (2008).

Castillo-Sang, M. et al. A malignant omental extra-gastrointestinal stromal tumor on a young man: a case report and review of the literature. World J. Surg. Oncol. 6, 50 (2008).

Franzini, C. et al. Extra-gastrointestinal stromal tumor of the greater omentum: report of a case and review of the literature. World J. Surg. Oncol. 6, 25 (2008).

Koshariya, M. et al. Gastrointestinal stromal tumor of gastrohepatic omentum in a patient with von Recklinghausen’s disease (neurofibromatosis type 1). Hepatogastroenterology 54, 2230–2231 (2007).

Kim, J. H. et al. Multiple malignant extragastrointestinal stromal tumors of the greater omentum and results of immunohistochemistry and mutation analysis: a case report. World J Gastroenterol 13, 3392–3395 (2007).

Todoroki, T. et al. Primary omental gastrointestinal stromal tumor (GIST). World J. Surg. Oncol. 5, 66 (2007).

Kaiser, A. M., Kang, J. C., Tolazzi, A. R., Sherrod, A. E. & Beart, R. J. Primary solitary extragastrointestinal stromal tumor of the greater omentum coexisting with ulcerative colitis. Dig Dis Sci 51, 1850–1852 (2006).

Darnell, A. et al. Gastrointestinal stromal tumors. Abdom. Imaging 31, 387–399 (2006).

Nakaya, I. et al. Malignant gastrointestinal stromal tumor originating in the lesser omentum, complicated by rapidly progressive glomerulonephritis and gastric carcinoma. Intern Med 43, 102–105 (2004).

Fukuda, H. et al. Gastrointestinal stromal tumor of the lesser omentum: report of a case. Surg. Today 31, 715–718 (2001).

Suzuki, K. et al. Malignant tumor, of the gastrointestinal stromal tumor type, in the greater omentum. J. Gastroenterol. 38, 985–988 (2003).

Nakagawa, M. et al. Extragastrointestinal stromal tumor of the greater omentum: case report and review of the literature. Hepatogastroenterology 50, 691–695 (2003).

Ortiz-Rey, J. A. et al. Fine needle aspiration appearance of extragastrointestinal stromal tumor. A case report. Acta Cytol. 47, 490–494 (2003).

Cai, N., Morgenstern, N. & Wasserman, P. A case of omental gastrointestinal stromal tumor and association with history of melanoma. Diagn. Cytopathol. 28, 342–344 (2003).

Tajima, K. et al. Expression of embryonic-form smooth muscle myosin heavy chain in a gastrointestinal stromal tumor of the greater omentum. Dig Dis Sci 46, 1629–1632 (2001).

Takahashi, T., Kuwao, S., Yanagihara, M. & Kakita, A. A primary solitary tumor of the lesser omentum with immunohistochemical features of gastrointestinal stromal tumors. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 93, 2269–2273 (1998).

Behammane, H. et al. Stromal tumor of the lesser omentum: a case report. Pan Afr Med J 17, 236 (2014).

Yamamoto, H. et al. c-kit and PDGFRA mutations in extragastrointestinal stromal tumor (gastrointestinal stromal tumor of the soft tissue). Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 28, 479–488 (2004).

Sakurai, S. et al. Myxoid epithelioid gastrointestinal stromal tumor (GIST) with mast cell infiltrations: a subtype of GIST with mutations of platelet-derived growth factor receptor alpha gene. Hum. Pathol. 35, 1223–1230 (2004).

Caricato, M. et al. An omental mass: any hypothesis? Colorectal Dis. 7, 417–418 (2005).

Hou, Y. Y. et al. [Clinicopathological, immunohistochemical and molecular genetic study of intra-abdomen extra-gastrointestinal stromal tumors]. Zhonghua Bing Li Xue Za Zhi 32, 422–426 (2003).

Zhu, J., Yang, Z., Tang, G. & Wang, Z. Extragastrointestinal stromal tumors: Computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging findings. Oncol. Lett. 9, 201–208 (2015).

Kim, K. H. et al. Diagnostic relevance of overexpressions of PKC-theta and DOG-1 and KIT/PDGFRA gene mutations in extragastrointestinal stromal tumors: a Korean six-centers study of 28 cases. Anticancer Res. 32, 923–937 (2012).

Goh, B. K. et al. A single-institution experience with eight CD117-positive primary extragastrointestinal stromal tumors: critical appraisal and a comparison with their gastrointestinal counterparts. J. Gastrointest. Surg. 13, 1094–1098 (2009).

Miettinen, M. et al. Gastrointestinal stromal tumors/smooth muscle tumors (GISTs) primary in the omentum and mesentery: clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical study of 26 cases. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 23, 1109–1118 (1999).

Yamamoto, H. et al. KIT-negative gastrointestinal stromal tumor of the abdominal soft tissue: a clinicopathologic and genetic study of 10 cases. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 35, 1287–1295 (2011).

Li, Z. Y., Huan, X. Q., Liang, X. J., Li, Z. S. & Tan, A. Z. Clinicopathological and immunohistochemical study of extra-gastrointestinal stromal tumors arising from the omentum and mesentery. Zhonghua Bing Li Xue Za Zhi 34, 11–14 (2005).

World Medical Association, Revising the Declaration of Helsinki. Bull Med Ethics. 158, 9–11 (2000).

Joensuu, H. Risk stratification of patients diagnosed with gastrointestinal stromal tumor. Hum. Pathol. 39, 1411–1419 (2008).

Acknowledgements

This study was supported in part by grants from the National Natural Scientific Foundation of China [NO. 31100643, 31570907, 81572306, 81502403, XJZT12Z03].

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

H.Z. and F.F. designed and instructed this study. F.F. drafted manuscript. F.F., Y.T. and Z.L. searched literatures. Y.T., Z.L., S.L. and G.X. input the data; F.F., Z.L., M.G. and X.L. analyzed the data. Daiming Fan revised manuscript.

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Feng, F., Tian, Y., Liu, Z. et al. Clinicopathological features and prognosis of omental gastrointestinal stromal tumor: evaluation of a pooled case series. Sci Rep 6, 30748 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep30748

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/srep30748

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.