Abstract

Magnetic proximity effect between two magnetic layers is an important focus of research for discovering new physical properties of magnetic systems. Antiferromagnets (AFMs) are fundamental systems with magnetic ordering and promising candidate materials in the emerging field of antiferromagnetic spintronics. However, the magnetic proximity effect between antiferromagnetic bilayers is rarely studied because detecting the spin orientation of AFMs is challenging. Using X-ray linear dichroism and magneto-optical Kerr effect measurements, we investigated antiferromagnetic proximity effects in epitaxial CoO/NiO/MgO(001) systems. We found the antiferromagnetic spin of the NiO underwent a spin reorientation transition from in-plane to out-of-plane with increasing NiO thickness, with the existence of vertical exchange spring spin alignment in thick NiO. More interestingly, the Néel temperature of the CoO layer was greatly enhanced by the adjacent NiO layer, with the extent of the enhancement closely dependent on the spin orientation of NiO layer. This phenomenon was attributed to different exchange coupling strengths at the AFM/AFM interface depending on the relative spin directions. Our results indicate a new route for modifying the spin configuration and ordering temperature of AFMs through the magnetic proximity effect near room temperature, which should further benefit the design of AFM spintronic devices.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Contact between materials with different magnetic orderings can modify their properties near the interface owing to exchange coupling. This phenomenon is usually called magnetic proximity effect. Investigation of the magnetic proximity effect has resulted in the discovery of many new rich physical phenomena1, such as the moments induced in heavy non-magnetic metals by proximity to ferromagnets (FMs) reported in a recent magneto-transport study2,3, and the enhancement of the Curie temperature (Tc) of diluted magnetic semiconductors due to the magnetic proximity effect of FMs1,4,5. The modification of magnetic properties influenced by magnetic proximity effect with FMs has been widely studied. For example, the Tc of FM has been found to be significantly enhanced in FM/FM bilayers6,7, which could be exploited to optimize magnetic properties in spintronic devices. Another well-known example is the manifestation of a shifted hysteresis loop (i.e., exchange bias)8,9 combined with enhanced coercivity, stronger magnetic anisotropy10,11 and spin reorientation transition12,13 for FMs in ferromagnet/antiferromagnet (AFM) bilayers owing to exchange coupling.

Antiferromagnetic materials, the other class of fundamental magnetic systems, have been widely used in advanced magnetic storage and sensor devices8. Recently, spintronic devices based on AFMs have been proposed14,15,16, which are predicted to realize stable high-density memory integration due to their zero moment and other nontrivial properties. However, tuning AFM magnetic properties is considered a great challenge due to its zero moment. Using exchange coupling with neighbor spins in FM/AFM bilayers, the Néel temperature (TN) of AFMs can be greatly enhanced17,18,19,20, and their spin orientation can be modulated through the formation of a lateral exchange spring spin structure14,15,21,22. Nevertheless, the tuning of the magnetic properties of AFMs without FM layer has drawn little attention. So far, there have only been few studies on the modulation of AFM magnetic properties using the AFM magnetic proximity effect in AFM/AFM bilayers. In AFM superlattices comprising two AFM materials with different TN, such as [CoO/NiO]n23,24,25,26 or [FeF2/CoF2]n27,28, the ordering temperature of the AFM layer with lower TN can be enhanced by the other AFM layer, and the AFM order has a long propagation length of several nanometers. Zhu et al. reported that interface coupling can induce AFM spin reorientation transition in the NiO/CoO/MgO(001) system29. However, how the spin orientation can be influenced by exchange coupling between AFM spins remains an unsettled question. It is also unclear whether the spin orientation of one AFM layer can affect the TN of the proximate AFM layer.

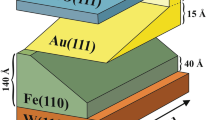

In this work, in order to detect the AFM properties of top CoO layers, we fabricated a single-crystalline CoO/NiO bilayer on MgO(001) substrate. NiO on MgO(001) substrate has out-of-plane AFM spin orientation owing to tensile strain30, whereas CoO on MgO(001) has in-plane AFM spin orientation owing to compressive strain31,32. Bulk NiO has a TN of ~523 K, and bulk CoO has a lower TN of ~293 K. These distinct spin orientations and TNs enable us to study the AFM proximity effect on AFM spin orientation and TN in this system. Using the element-specific X-ray magnetic linear dichroism (XMLD) effect, we demonstrate that the AFM spin orientation of NiO changes from in-plane to out-of-plane with increasing NiO thickness, and the existence of a vertical exchange spring alignment in thick NiO. The spin reorientation transition (SRT) in NiO layer dramatically lowers the TN of the adjacent CoO layer. Further confirmed by systematical magneto-optical Kerr effect (MOKE) measurements of the Fe/CoO/NiO/MgO(001) system, this phenomenon of spin-orientation-dependent TN was attributed to the exchange coupling strength dependent on the spin orientation. The AFM order propagation length was explored by studying the CoO-thickness dependent TN. Our results provide clear evidence that the magnetic proximity effect in AFM/AFM bilayers can influence the spin direction and ordering temperature within 2–3 nm of the interface, which is crucial for designing AFM spintronic devices.

Results

Antiferromagnetic spin orientation transition in CoO/NiO bilayer

We applied XMLD measurements to determine the AFM spin orientation in a single-crystalline CoO/NiO bilayer on a MgO(001) surface using the total electron yield (TEY) mode. In XMLD measurements, the obtained X-ray absorption spectrum (XAS) is strongly dependent on the relative orientation of the AFM spin axis and the linear polarization vector of the X-rays used29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36. Thus, to determine whether the AFM spin was in-plane or out-of-plane, XAS was measured as a function of the incident angle ( ), defined as the angle between the propagation direction of the X-rays and the direction normal to the sample surface, as shown in Fig. 1(a). To investigate the magnetic properties of the CoO layer, CoO L3 edge spectra were measured with X-rays at normal incidence (

), defined as the angle between the propagation direction of the X-rays and the direction normal to the sample surface, as shown in Fig. 1(a). To investigate the magnetic properties of the CoO layer, CoO L3 edge spectra were measured with X-rays at normal incidence ( ) and grazing incidence (

) and grazing incidence ( or

or  ). Figure 1 shows the results of XMLD measurements performed at 78 K, which is much lower than the TN of both NiO and CoO films in our samples13,29,35. As shown in Fig. 1(e), the XAS spectra observed for 2 nm CoO proximate to 2 nm and 12 nm NiO were similar to that of CoO/MgO, which exhibits in-plane spin orientation29,32. Thus, at low temperature, the CoO AFM spin was aligned in-plane on top of both 2 nm and 12 nm NiO. Figure 1(f) shows the typical XAS measured at the Ni2+ L2 edge, in which the doublet spectra have been normalized to the intensity of the lower energy peak. The second peak of the XAS obtained from the 2 nm NiO in the CoO/NiO bilayer exhibited a clearly reversed intensity for

). Figure 1 shows the results of XMLD measurements performed at 78 K, which is much lower than the TN of both NiO and CoO films in our samples13,29,35. As shown in Fig. 1(e), the XAS spectra observed for 2 nm CoO proximate to 2 nm and 12 nm NiO were similar to that of CoO/MgO, which exhibits in-plane spin orientation29,32. Thus, at low temperature, the CoO AFM spin was aligned in-plane on top of both 2 nm and 12 nm NiO. Figure 1(f) shows the typical XAS measured at the Ni2+ L2 edge, in which the doublet spectra have been normalized to the intensity of the lower energy peak. The second peak of the XAS obtained from the 2 nm NiO in the CoO/NiO bilayer exhibited a clearly reversed intensity for  and

and  compared with those from the NiO film grown on MgO substrate, which indicates that AFM spin of 2 nm NiO was aligned out of plane on MgO substrate29,30 [Fig. 1(b)] and in plane in AFM bilayer [Fig. 1(c)]. However, the second peak in the NiO XAS spectrum of the CoO (2 nm)/NiO (12 nm) bilayer showed similar intensity at

compared with those from the NiO film grown on MgO substrate, which indicates that AFM spin of 2 nm NiO was aligned out of plane on MgO substrate29,30 [Fig. 1(b)] and in plane in AFM bilayer [Fig. 1(c)]. However, the second peak in the NiO XAS spectrum of the CoO (2 nm)/NiO (12 nm) bilayer showed similar intensity at  and

and  . Thus, we can conclude that the AFM spins of the 12 nm NiO were in the canting state with comparable in-plane and out-of-plane components. This result is significantly different from that reported for a reversed growth order in NiO (12 nm)/CoO bilayer on MgO(001) substrate, which showed out-of-plane AFM spin orientation of the NiO29. Due to the limited electron escape length in NiO35, the observed intensity of the XAS measurements in TEY mode mostly came from a several nanometer thickness of the NiO films. Thus, the XAS from the 12-nm NiO layer shown in Fig. 1(f) reflects the properties of the NiO near the CoO/NiO interface, whereas previous measurements on NiO/CoO bilayers only revealed the information for the NiO away from the NiO/CoO interface29.

. Thus, we can conclude that the AFM spins of the 12 nm NiO were in the canting state with comparable in-plane and out-of-plane components. This result is significantly different from that reported for a reversed growth order in NiO (12 nm)/CoO bilayer on MgO(001) substrate, which showed out-of-plane AFM spin orientation of the NiO29. Due to the limited electron escape length in NiO35, the observed intensity of the XAS measurements in TEY mode mostly came from a several nanometer thickness of the NiO films. Thus, the XAS from the 12-nm NiO layer shown in Fig. 1(f) reflects the properties of the NiO near the CoO/NiO interface, whereas previous measurements on NiO/CoO bilayers only revealed the information for the NiO away from the NiO/CoO interface29.

(a) Schematic of XMLD measurement geometry. (b–d) Schematics of AFM spin configurations with arrows representing the AFM spin alignments. In (d),  is defined as the spin canting angle between the film surface and spin orientation and z is the depth from the CoO/NiO interface. XAS spectra with

is defined as the spin canting angle between the film surface and spin orientation and z is the depth from the CoO/NiO interface. XAS spectra with  and

and  or

or  of (e) Co2+ L3 edge and (f) Ni2+ L2 edge in NiO(CoO)/MgO(001) and CoO/NiO/MgO(001) samples at 78 K. The unit of the thickness in (e,f) is nm. The XMLD measurements of NiO, CoO, and CoO/NiO were performed on different samples.

of (e) Co2+ L3 edge and (f) Ni2+ L2 edge in NiO(CoO)/MgO(001) and CoO/NiO/MgO(001) samples at 78 K. The unit of the thickness in (e,f) is nm. The XMLD measurements of NiO, CoO, and CoO/NiO were performed on different samples.

The XMLD effect of CoO can be quantified by the L3 ratio  , which is defined as the ratio of the intensities of the XAS peaks at 777 eV and 779.6 eV [marked as A and B in Fig. 1(e), respectively]32. For NiO, the XMLD effect is quantitatively described by the NiO L2 ratio

, which is defined as the ratio of the intensities of the XAS peaks at 777 eV and 779.6 eV [marked as A and B in Fig. 1(e), respectively]32. For NiO, the XMLD effect is quantitatively described by the NiO L2 ratio  , which is defined as the ratio of the intensity of the lower energy peak divided by that of the higher energy peak30,35. Figure 2(a,c) respectively show the NiO-thickness-dependent CoO L3 ratio

, which is defined as the ratio of the intensity of the lower energy peak divided by that of the higher energy peak30,35. Figure 2(a,c) respectively show the NiO-thickness-dependent CoO L3 ratio  and NiO L2 ratio

and NiO L2 ratio  measured at incidence angles of 0o and 70o at 78 K. In Fig. 2(a), the CoO

measured at incidence angles of 0o and 70o at 78 K. In Fig. 2(a), the CoO  is always larger than

is always larger than  at various NiO thicknesses. Consequently, the difference of the CoO L3 ratio

at various NiO thicknesses. Consequently, the difference of the CoO L3 ratio

is positive for all NiO thicknesses in Fig. 2(b). This result indicates that the CoO spin aligns in plane irrespective of the NiO thickness, which may be attributed to the large anisotropy of the CoO layer37,38. The XMLD of the NiO film showed a more complicated behavior. In Fig. 2(c),

is positive for all NiO thicknesses in Fig. 2(b). This result indicates that the CoO spin aligns in plane irrespective of the NiO thickness, which may be attributed to the large anisotropy of the CoO layer37,38. The XMLD of the NiO film showed a more complicated behavior. In Fig. 2(c),  was smaller than

was smaller than  for NiO thicknesses smaller than 4 nm, after which

for NiO thicknesses smaller than 4 nm, after which  began to increase while

began to increase while  began to decrease, and they crossed over at dNiO~7.0 nm. Correspondingly, in Fig. 2(d), the difference of NiO L2 ratio,

began to decrease, and they crossed over at dNiO~7.0 nm. Correspondingly, in Fig. 2(d), the difference of NiO L2 ratio,  , changed from a negative value to a small positive value at 78 K. It has been shown that the NiO L2 ratio

, changed from a negative value to a small positive value at 78 K. It has been shown that the NiO L2 ratio  should be smaller for

should be smaller for  than

than  when the NiO spin is aligned along the <100> direction29,30,34. Thus, the data in Fig. 2(c,d) indicate that the NiO spin orientation switched from in-plane to a canting orientation at 78 K. NiO-thickness-dependent experiments were also performed at 300 K and 400 K. As shown in Fig. 2(d), the NiO

when the NiO spin is aligned along the <100> direction29,30,34. Thus, the data in Fig. 2(c,d) indicate that the NiO spin orientation switched from in-plane to a canting orientation at 78 K. NiO-thickness-dependent experiments were also performed at 300 K and 400 K. As shown in Fig. 2(d), the NiO  at 300 K changed from negative to positive, indicating that the NiO spin switched from in-plane to out-of-plane. The NiO

at 300 K changed from negative to positive, indicating that the NiO spin switched from in-plane to out-of-plane. The NiO  at 400 K showed a rapid increase at dNiO~2.0 nm, which was related to the establishment of NiO AFM order29.

at 400 K showed a rapid increase at dNiO~2.0 nm, which was related to the establishment of NiO AFM order29.

NiO-spin-orientation-dependent enhancement of CoO TN

The XMLD effect observed at the Co2+ L3 edge and Ni2+ L2 edge can generally be attributed to AFM ordering and the crystal-field effect33,39. While the AFM contribution decreases with increasing temperature and vanishes above TN, the contribution of the crystal field only slightly decreases at higher temperature. Thus, the TN of the AFM layer could be identified from the transition point of the CoO  curve and NiO

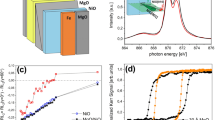

curve and NiO  curve29. Temperature-dependent XMLD measurements were performed as shown in Fig. 3. In Fig. 3(a–c), the Co2+

curve29. Temperature-dependent XMLD measurements were performed as shown in Fig. 3. In Fig. 3(a–c), the Co2+  was always positive, indicating in-plane aligned Co2+ AFM spins. The different CoO

was always positive, indicating in-plane aligned Co2+ AFM spins. The different CoO  value at high temperature could be attributed to a change of the crystal field influenced by different strain in the CoO layer. The single 2-nm CoO layer exhibited a TN of 230 K [Fig. 3(a)]. When the CoO layer was proximate to 2 nm NiO, its TN was dramatically enhanced to 400 K [Fig. 3(b)], whereas the TN of the CoO layer on top of 12 nm NiO was only enhanced to 300 K [Fig. 3(c)]. This result seems unexpected because the Néel temperature of 12 nm NiO is evidently higher than that of 2 nm NiO owing to the finite-size scaling13.

value at high temperature could be attributed to a change of the crystal field influenced by different strain in the CoO layer. The single 2-nm CoO layer exhibited a TN of 230 K [Fig. 3(a)]. When the CoO layer was proximate to 2 nm NiO, its TN was dramatically enhanced to 400 K [Fig. 3(b)], whereas the TN of the CoO layer on top of 12 nm NiO was only enhanced to 300 K [Fig. 3(c)]. This result seems unexpected because the Néel temperature of 12 nm NiO is evidently higher than that of 2 nm NiO owing to the finite-size scaling13.

Using the advantages of XMLD with elementary specification, we also measured the temperature-dependent  of the NiO layer in CoO/NiO bilayer as shown in Fig. 3(d–f). Our measurements indicated that the 2 nm NiO had a TN of ~400 K, which coincides with the changes in the NiO

of the NiO layer in CoO/NiO bilayer as shown in Fig. 3(d–f). Our measurements indicated that the 2 nm NiO had a TN of ~400 K, which coincides with the changes in the NiO  seen in Fig. 2(d). Owing to the temperature-dependent crystal field effect31,33, the

seen in Fig. 2(d). Owing to the temperature-dependent crystal field effect31,33, the  of the 2 nm NiO still decreased above its TN. The

of the 2 nm NiO still decreased above its TN. The  of 2 nm NiO in the AFM bilayer was negative at low temperature and became positive approaching 400 K, which indicates that the NiO spin had in-plane orientation at low temperature, and then switched to out-of-plane at high temperature [Fig. 3(e)]. In Fig. 3(f), the

of 2 nm NiO in the AFM bilayer was negative at low temperature and became positive approaching 400 K, which indicates that the NiO spin had in-plane orientation at low temperature, and then switched to out-of-plane at high temperature [Fig. 3(e)]. In Fig. 3(f), the  of 12 nm NiO had a small positive value at low temperature, and started to increase when the temperature approached 300 K. This indicates that the NiO spin at the CoO/NiO interface changed from the canting state to an out-of-plane oriented state. Note that the SRT of the NiO layer occurred exactly at the TN of the proximate CoO layer, which could be ascribed to the decreased interfacial coupling strength in the AFM bilayer related to the weakened CoO AFM order. Based on these results, we can conclude that the NiO layer with in-plane aligned spin orientation largely enhanced the TN of the adjacent CoO layer by 170 K whereas the NiO layer with out-of-plane spin orientation only enhanced the TN of the CoO layer by 70 K. It should be pointed out that, as a result of thickness dependent lattice relaxation, the strain of the film grown on thick NiO may be different to that of the film grown on thin NiO. However, the observed different TNs are unlikely to be attributable to the different strains of the two systems. High energy electron diffraction (RHEED) patterns of the 2- and 12-nm NiO films showed that the difference in lattice constant was less than 0.6%. However, as reported in ref. 31, while the difference in lattice constant between bulk MnO and Ag can be 8.2%, the TN of CoO film grown on Ag(001) substrate is only 20 K higher than that grown on MnO(001) film.

of 12 nm NiO had a small positive value at low temperature, and started to increase when the temperature approached 300 K. This indicates that the NiO spin at the CoO/NiO interface changed from the canting state to an out-of-plane oriented state. Note that the SRT of the NiO layer occurred exactly at the TN of the proximate CoO layer, which could be ascribed to the decreased interfacial coupling strength in the AFM bilayer related to the weakened CoO AFM order. Based on these results, we can conclude that the NiO layer with in-plane aligned spin orientation largely enhanced the TN of the adjacent CoO layer by 170 K whereas the NiO layer with out-of-plane spin orientation only enhanced the TN of the CoO layer by 70 K. It should be pointed out that, as a result of thickness dependent lattice relaxation, the strain of the film grown on thick NiO may be different to that of the film grown on thin NiO. However, the observed different TNs are unlikely to be attributable to the different strains of the two systems. High energy electron diffraction (RHEED) patterns of the 2- and 12-nm NiO films showed that the difference in lattice constant was less than 0.6%. However, as reported in ref. 31, while the difference in lattice constant between bulk MnO and Ag can be 8.2%, the TN of CoO film grown on Ag(001) substrate is only 20 K higher than that grown on MnO(001) film.

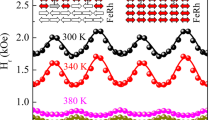

In order to systematically investigate how the TN of the CoO film changed with NiO thickness, a sample of Fe (2 nm)/CoO(1.5 nm)/NiO/MgO(001) was prepared with a wedge-shaped NiO layer. It is well known that below the TN, the antiferromagnetic spins in a FM/AFM bilayer can dramatically increase the coercivity (Hc) of FM layer through the exchange coupling between the FM layer and AFM layer. Thus, the TN of the CoO layer could be determined from temperature-dependent behavior of its Hc8,20. Figure 4(a–c) show typical hysteresis loops obtained at different temperatures for Fe/CoO, Fe/CoO/NiO (2 nm), and Fe/CoO/NiO (12 nm), respectively. The samples exhibited easy hysteresis loops with negligible exchange bias field under a sweeping field H parallel to the cooling field  along the CoO<110> directions11,32. The temperature-dependent Hc is plotted in Fig. 4(d), the inset of which shows the enlarged region around the TN of the CoO layer, which is defined as the discontinuity point of the slope of the Hc(T) curve. From this plot, the TN of the 1.5-nm CoO single layer can be judged to be about 175 K. For CoO on top of 2 nm NiO, the TN was enhanced to 415 K, while that of CoO on top of 12 nm NiO was enhanced to 343 K.

along the CoO<110> directions11,32. The temperature-dependent Hc is plotted in Fig. 4(d), the inset of which shows the enlarged region around the TN of the CoO layer, which is defined as the discontinuity point of the slope of the Hc(T) curve. From this plot, the TN of the 1.5-nm CoO single layer can be judged to be about 175 K. For CoO on top of 2 nm NiO, the TN was enhanced to 415 K, while that of CoO on top of 12 nm NiO was enhanced to 343 K.

Typical hysteresis loops for the systems (a) Fe/CoO/MgO(001) and (b,c) Fe/CoO/NiO/MgO(001) with indicated layer thicknesses at different temperatures. (d) Temperature-dependent Hc of Fe/CoO/NiO/MgO(001) with different NiO thickness. Inset shows an enlargement of the Hc around TN. Arrows denote the CoO TN evaluated from the discontinuity of the slopes of the Hc(T) curves. (e) CoO TN as a function of NiO thickness for the Fe/CoO/NiO(wedge)/MgO(001) sample. Inset in (e) shows the structure of the sample.

Figure 4(e) shows the results of the systematical measurement of CoO TN as a function of NiO thickness. The TN of the 1.5-nm CoO layer first increased to ~400 K with NiO thickness, began to decrease for NiO thicker than 4 nm, and finally saturated to ~340 K for NiO thicker than 8 nm. The TN of CoO decreased by ~80 K on thicker NiO, which is consistent with the XMLD results. Recalling the fact that the SRT of NiO occurred at a thickness range of 4–8 nm at temperatures of 300–400 K in Fig. 2(d), the results here further confirm that the TN of the CoO layer was closely related to the spin orientation of the proximate NiO layer. Therefore, in Fig. 2(b), for the CoO layer on top of thick NiO film, the  for CoO at 300 K is similar to that observed at 400 K, indicating the paramagnetic state of CoO at 300 K. However, for CoO layers proximate to NiO layers thinner than 6 nm, we found a small difference in the CoO

for CoO at 300 K is similar to that observed at 400 K, indicating the paramagnetic state of CoO at 300 K. However, for CoO layers proximate to NiO layers thinner than 6 nm, we found a small difference in the CoO  measured at 300 K and 400 K, which indicates that the AFM order of the CoO layer on top of thin NiO film persisted above 300 K.

measured at 300 K and 400 K, which indicates that the AFM order of the CoO layer on top of thin NiO film persisted above 300 K.

Propagation of CoO AFM order in CoO/NiO bilayer

We have shown that exchange coupling in the CoO/NiO bilayer enhanced the CoO TN. This enhancement of the CoO ordering temperature was expected to be at a maximum near the CoO/NiO interface owing to the interfacial nature of exchange coupling. Thus, the ordering temperature of the CoO should gradually change along the thickness direction, as indicated by the schematic in Fig. 5(a). For a sufficiently thick CoO film, the ordering temperature of the outer part of the CoO layer is expected to be close to that of bulk CoO. However, this theory is hard to prove using XMLD measurements. Figure 4(b) shows the temperature-dependent  of 2 nm CoO in the CoO/NiO bilayer had a clear transition which indicated a TN of ~400 K. In contrast, it only gradually decreased with temperature for 4 nm CoO, and no obvious transition could be distinguished. Thus, it was difficult to determine the ordering temperature of 4 nm CoO using XMLD measurements. As indicated in Fig. 5(a), different parts of the 4-nm CoO layer had different ordering temperature; thus, the XMLD measurements detected all the AFM information, and did not show the single phase transition.

of 2 nm CoO in the CoO/NiO bilayer had a clear transition which indicated a TN of ~400 K. In contrast, it only gradually decreased with temperature for 4 nm CoO, and no obvious transition could be distinguished. Thus, it was difficult to determine the ordering temperature of 4 nm CoO using XMLD measurements. As indicated in Fig. 5(a), different parts of the 4-nm CoO layer had different ordering temperature; thus, the XMLD measurements detected all the AFM information, and did not show the single phase transition.

(a) Schematic of AFM order in the AFM bilayer. (b) CoO L3 ratio difference  as a function of temperature for CoO/NiO (2 nm)/MgO(001) with a different CoO thickness. (c) Temperature dependence of Hc for Fe/CoO/NiO (2 nm)/MgO(001) with a different CoO thickness. Inset shows an enlargement of the Hc around TN. (d) TN of CoO layer as a function of CoO thickness with and without a proximate 2-nm NiO layer. Inset in (d) shows the structure of the sample.

as a function of temperature for CoO/NiO (2 nm)/MgO(001) with a different CoO thickness. (c) Temperature dependence of Hc for Fe/CoO/NiO (2 nm)/MgO(001) with a different CoO thickness. Inset shows an enlargement of the Hc around TN. (d) TN of CoO layer as a function of CoO thickness with and without a proximate 2-nm NiO layer. Inset in (d) shows the structure of the sample.

To determine the CoO AFM order away from the AFM interface, we grew 2 nm Fe on top of CoO/NiO (2 nm)/MgO(001) with the CoO grown into a wedge shape, and used MOKE measurements to determine the ordering temperature of the CoO spins at the Fe/CoO interface through the interfacial exchange coupling. As shown in Fig. 5(c), the temperature-dependent Hc obtained from the magnetic hysteresis loops showed a clear transition. The TN of 1.5 nm, 2 nm, and 5 nm CoO was determined to be 430 K, 380 K, and 330 K, respectively. Half of the sample was grown as Fe (2 nm)/CoO(wedge) without the NiO underlayer, as indicated by the inset in Fig. 5(d), thus both the Fe/CoO/NiO and Fe/CoO samples had identical growth conditions. Figure 5(d) shows the TN at the Fe/CoO interface as a function of CoO thickness for both Fe/CoO/NiO and Fe/CoO samples. The TN of CoO in the AFM bilayer was always higher than that without the NiO layer. Therefore, our results demonstrate that the exchange coupling at the CoO/NiO interface can significantly enhance the ordering temperature of CoO. Without the NiO underlayer, the TN of the CoO layer followed the finite size scaling law well, as previously reported13. However, with the NiO layer, the TN of the CoO first increased with thickness and then decreased exponentially when the CoO thickness was larger than 1.5 nm. In both Fe/CoO/NiO and Fe/CoO samples, the determined TN for thick CoO saturated at ~300 K, which is close to the bulk TN of CoO. The TN measured for the CoO/NiO bilayer first increased with CoO thickness owing to the finite size effect. However, the induced AFM order of the CoO in CoO/NiO bilayer should not have a higher ordering temperature than the NiO layer, and the AFM order of the CoO spins in the outer layer weakens in thick CoO film, so the measured TN decreased for CoO thicknesses above 1.5 nm. By fitting TN(dCoO) with an exponential decay function for dCoO > 1.5 nm, we obtained a characteristic decaying thickness of ~0.7 nm. Our results indicate that the propagation length of AFM order in CoO is about 2–3 nm.

Discussion

The anisotropy of CoO is about two orders of magnitude stronger than that of NiO38, thus the CoO spins in the CoO/NiO bilayer were always in-plane, whereas the spin orientation of the NiO layer was influenced by the competition between interfacial exchange coupling and lattice-strain-induced out-of-plane anisotropy29. The interfacial exchange coupling should be collinear coupling, because the thin NiO spins were driven to align along the film plane by the in-plane CoO spins. However, in the AFM bilayer with thick NiO, the AFM proximity effect weakened with distance from the CoO/NiO interface24,25,26, while the strain-induced anisotropy in the NiO persisted above 20 nm in our experiment. Thus, for NiO far from the CoO/NiO interface, the AFM NiO spin was aligned out of plane, while near the interface the AFM spin was in the canting state [Fig. 1(f)]. In this case, it is natural to suppose a vertical exchange spring spin alignment existed in the thicker NiO layers, as shown in Fig. 1(d), which has never been reported before. Within the detection length of the XMLD measurements, the NiO AFM spins were found to change from in-plane to the canting orientation with increasing NiO thickness at low temperature.

Figure 3(e,f) show that the NiO spins changed from in-plane (canting state) to out-of-plane with increasing temperature; this can be understood by the weakened exchange coupling strength at the NiO/CoO interface at high temperature. The AFM exchange coupling strength was also related to the AFM spin orientation, as described by  , where

, where  and

and  represent CoO and NiO spin, and

represent CoO and NiO spin, and  is the interfacial exchange coupling constant. Because the CoO spin was aligned in-plane, the AFM exchange coupling strength should have become smaller when the NiO spin rotated from in-plane to out-of-plane. It is therefore reasonable that a drop in CoO TN was observed when the spin orientation of the proximate NiO layer changed from in-plane to out-of-plane. Monte Carlo simulation with some typical parameters qualitatively confirmed our experimental results (see Supplementary Fig. S2). The length of AFM order propagation in the CoO layer of the CoO/NiO bilayer was estimated to be 2–3 nm. In terms of previous reports on CoO/NiO superlattices, this value is similar to that in ref. 26 and smaller than that in ref. 25, which can be attributed to different film qualities resulting from the use of different growth methods. Moreover, such AFM order propagation in the AFM bilayer was also confirmed qualitatively by Monte Carlo simulation (see Supplementary Fig. S3).

is the interfacial exchange coupling constant. Because the CoO spin was aligned in-plane, the AFM exchange coupling strength should have become smaller when the NiO spin rotated from in-plane to out-of-plane. It is therefore reasonable that a drop in CoO TN was observed when the spin orientation of the proximate NiO layer changed from in-plane to out-of-plane. Monte Carlo simulation with some typical parameters qualitatively confirmed our experimental results (see Supplementary Fig. S2). The length of AFM order propagation in the CoO layer of the CoO/NiO bilayer was estimated to be 2–3 nm. In terms of previous reports on CoO/NiO superlattices, this value is similar to that in ref. 26 and smaller than that in ref. 25, which can be attributed to different film qualities resulting from the use of different growth methods. Moreover, such AFM order propagation in the AFM bilayer was also confirmed qualitatively by Monte Carlo simulation (see Supplementary Fig. S3).

In general, the XMLD signal should reflect the AFM spin alignment, so if the spin configuration in the NiO film is known, the NiO-thickness dependent XMLD signal in Fig. 2 can be quantitatively simulated. The NiO XMLD signal could be expressed as  40, where

40, where  is the electron escape depth and

is the electron escape depth and  is the XMLD signal of the NiO layer at the position with depth

is the XMLD signal of the NiO layer at the position with depth  away from the CoO/NiO interface, and depends on the local spin canting angle

away from the CoO/NiO interface, and depends on the local spin canting angle  at

at  , i.e.

, i.e.  , as defined in Fig. 1(d).

, as defined in Fig. 1(d).  may be reasonably expressed as

may be reasonably expressed as  33. In Fig. 2(d),

33. In Fig. 2(d),  for in-plane aligned NiO spin, and

for in-plane aligned NiO spin, and  for out-of-plane aligned NiO spin at a higher temperature. Thus, we can determine B = 0.3 and A = −0.51. The

for out-of-plane aligned NiO spin at a higher temperature. Thus, we can determine B = 0.3 and A = −0.51. The  -dependent spin profile was calculated by Monte Carlo simulation (see Supplementary part 2), and the

-dependent spin profile was calculated by Monte Carlo simulation (see Supplementary part 2), and the  -dependent

-dependent  was then calculated by choosing a suitable value for

was then calculated by choosing a suitable value for  . The green line in Fig. 2(d) shows the calculated

. The green line in Fig. 2(d) shows the calculated  with

with  = 4.0 nm, which agrees well with the experimental result observed at low temperature. Our calculations further verified the model with the AFM exchange spring structure shown in Fig. 1(d). Based on the XMLD transition thickness in Fig. 2(d), the length scale of the AFM exchange spring was estimated to be ~6 nm at 78 K, and became smaller at higher temperature owing to the weakening of the exchange coupling.

= 4.0 nm, which agrees well with the experimental result observed at low temperature. Our calculations further verified the model with the AFM exchange spring structure shown in Fig. 1(d). Based on the XMLD transition thickness in Fig. 2(d), the length scale of the AFM exchange spring was estimated to be ~6 nm at 78 K, and became smaller at higher temperature owing to the weakening of the exchange coupling.

It should be noted that the  of thick NiO film depends on the vertical spin profile, which could be different in the systems with different NiO thickness. In our Monte Carlo simulations, the

of thick NiO film depends on the vertical spin profile, which could be different in the systems with different NiO thickness. In our Monte Carlo simulations, the  -dependent spin profile was strongly dependent on the exchange coupling constants and AFM magnetic anisotropies, and these parameters are difficult to determine experimentally. XMLD measurements can only indicate the average AFM properties, and quantitatively determining the AFM spin profile across the film requires other techniques with layer specification. We note that the FM magnetization profile of magnetic heterostructures can be investigated by X-ray resonant magnetic reflectometry based on the X-ray magnetic circular dichroism effect41. Thus, the study of non-uniform AFM spin alignment in AFM films is likely to be possible using X-ray resonant magnetic reflectometry based on the XMLD effect.

-dependent spin profile was strongly dependent on the exchange coupling constants and AFM magnetic anisotropies, and these parameters are difficult to determine experimentally. XMLD measurements can only indicate the average AFM properties, and quantitatively determining the AFM spin profile across the film requires other techniques with layer specification. We note that the FM magnetization profile of magnetic heterostructures can be investigated by X-ray resonant magnetic reflectometry based on the X-ray magnetic circular dichroism effect41. Thus, the study of non-uniform AFM spin alignment in AFM films is likely to be possible using X-ray resonant magnetic reflectometry based on the XMLD effect.

In summary, we investigated the AFM proximity effect in a CoO/NiO/MgO(001) system on the basis of AFM spin orientation, Néel temperature, and AFM order propagation length. Owing to AFM interfacial exchange coupling, the NiO AFM spin underwent SRT from in-plane to out-of-plane with increasing NiO thickness, with the existence of a vertical exchange spring structure in thick NiO. The SRT had a great influence on the TN of the CoO layer, and influenced the AFM order of the CoO within a limited depth of about 2–3 nm from the interface. The present work is expected to allow new designs for AFM-based devices that exploit the AFM proximity effect in AFM/AFM bilayers, where the AFM spin orientation and AFM ordering temperature can be manipulated without involving any FM layer.

Methods

Sample preparation

CoO/NiO/MgO(001) films were prepared by molecular beam epitaxy (MBE) in an ultra-high vacuum (UHV) chamber with a base pressure of 2 × 10−10 Torr. The single-crystal MgO(001) substrate was first annealed at 600 °C for 30 min in the UHV chamber, followed by the growth of a 10-nm MgO seed layer at 500 °C by e-beam evaporation. Subsequently, the NiO and CoO layers were prepared by reactive deposition of Ni and Co at an oxygen pressure of 1 × 10−6 Torr at room temperature (RT)11,29,32. A smooth surface was confirmed by the sharp reflection RHEED patterns. Film thickness was determined by the deposition rate (~1.0–2.0 Å/min), and was measured using a calibrated quartz thickness monitor. For thickness-dependence measurements, the CoO(NiO) film was grown in a wedge shape by moving the substrate behind a knife-edge shutter. To study the exchange coupling between CoO AFM spins and Fe FM spins, Fe film was grown on the bilayers by MBE at RT. In situ RHEED patterns indicated high quality epitaxial growth of both the fcc structured CoO (NiO) films and the bcc Fe film with an epitaxial relationship of Fe[100]//CoO[110]//NiO[110]//MgO[110] (see Supplementary Fig. S1). Finally, the sample was capped with a 3-nm MgO layer as a protective layer for MOKE measurements. For the samples subjected to XMLD measurements, a Al (4-nm)/MgO (1-nm) bilayer was capped on top of the CoO layer to prevent charging effects, and a 1-nm MgO layer was used to prevent a chemical reaction between the Al and CoO.

XMLD measurements

XMLD measurements were performed at the bending-magnet Beamline 08B of the National Synchrotron Radiation Research Center (NSRRC) in Taiwan. The X-ray polarization was fixed along the horizontal direction and spectra were collected in total electron yield mode. The absorption spectra were collected for both normal ( ) and grazing (

) and grazing ( or 70°) X-ray incidence29,31,32. The linear background has been subtracted for all of the XAS spectra shown in this paper. Samples were mounted with the slope of the NiO wedge along the vertical direction so that the NiO thickness could be easily varied by moving the sample up and down to illuminate the sample at different positions. The X-ray beam size was estimated to be 100 μm along the vertical direction and 300 μm along the horizontal direction. Accordingly, the thickness variation in the vertical direction within the X-ray beam caused by the wedge shape was less than 0.2 nm. The sample temperature was adjustable in the range of 78–460 K with a precision of less than 0.1 K.

or 70°) X-ray incidence29,31,32. The linear background has been subtracted for all of the XAS spectra shown in this paper. Samples were mounted with the slope of the NiO wedge along the vertical direction so that the NiO thickness could be easily varied by moving the sample up and down to illuminate the sample at different positions. The X-ray beam size was estimated to be 100 μm along the vertical direction and 300 μm along the horizontal direction. Accordingly, the thickness variation in the vertical direction within the X-ray beam caused by the wedge shape was less than 0.2 nm. The sample temperature was adjustable in the range of 78–460 K with a precision of less than 0.1 K.

MOKE measurements

The magnetic properties of the films were determined by MOKE measurement using a laser diode with a wavelength of 670 nm. By taking advantage of the small laser beam size (below 0.2 mm) of the MOKE apparatus, we were able to systematically perform thickness-dependent studies on the same wedge-shaped sample as that used in XMLD measurements. The sample temperature for the MOKE measurements was adjustable in the range of 80–500 K.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Li, Q. et al. Antiferromagnetic proximity effect in epitaxial CoO/NiO/MgO(001) systems. Sci. Rep. 6, 22355; doi: 10.1038/srep22355 (2016).

References

Manna, P. K. & Yusuf, S. M. Two interface effects: Exchange bias and magnetic proximity. Phy. Rep. 535, 61–99 (2014).

Huang, S. Y. et al. Transport magnetic proximity effects in platinum. Phys. Rev. Lett. 109, 107204 (2012).

Yu, Y. M. et al. Pt magnetic polarization on Y3Fe5O12 and magnetotransport characteristics. Phys. Rev. Lett. 110, 147207 (2013).

Maccherozzi, F. et al. Evidence for a magnetic proximity effect up to room temperature at Fe/(Ga,Mn)As interfaces. Phys. Rev. Lett. 101, 267201 (2008).

Olejnik, K. et al. Exchange bias in a ferromagnetic semiconductor induced by a ferromagnetic metal: Fe/(Ga,Mn)As bilayer films studied by XMCD measurements and SQUID magnetometry. Phys. Rev. B 81, 104402 (2010).

Choi, H. J. et al. Curie temperature enhancement and induced Pd magnetic moments for ultrathin Fe films grown on stepped Pd(001). Phys. Rev. Lett. 82, 1947 (1999).

Vargas, J. M., Gomez, J., Zysler, R. D. & Butera, A. Thermal stabilization of magnetic nanoparticles embedded in a ferromagnetic matrix, Nanotechnology 18, 115714 (2007).

Nogués, J. & Shuller, I. K. Exchange bias. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 192, 203–232 (1999).

Kiwi, M. J. Exchange bias theory. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 234, 584–595 (2001).

Grimsditch, M., Hoffman, A., Vavassori, P., Shi, H. T. & Lederman, D. Exchange-induced anisotropies at ferromagnetic-antiferromagnetic interfaces above and below the Néel Temperature. Phys. Rev. Lett. 90, 257201 (2003).

Cao, W. N. et al. Temperature-dependent magnetic anisotropies in epitaxial Fe/CoO/MgO(001) system studied by the planar Hall effect. Appl. Phys. Lett. 98, 262506 (2011).

Wang, B. Y. et al. Driving magnetization perpendicular by antiferromagnetic-ferromagnetic exchange coupling, Phys. Rev. B 83, 104417 (2011).

Li, Q. et al. Multiple in-plane spin reorientation transitions in Fe/CoO bilayers grown on vicinal MgO(001), Phys. Rev. B 91, 104424 (2015).

Park, B. G. et al. A spin-valve-like magnetoresistance of an antiferromagnet-based tunnel junction. Nat. Mater. 10, 347–351 (2011).

Wang, Y. Y. et al. Room-temperature perpendicular exchange coupling and tunneling anisotropic magnetoresistance in an antiferromagnet-based tunnel junction. Phys. Rev. Lett. 109, 137201 (2012).

Marti, X. et al. Room-temperature antiferromagnetic memory resistor. Nat. Mater. 13, 367–374 (2014).

Borchers, J. A. et al. Long-range magnetic order in Fe3O4/NiO superlattices, Phy. Rev. B 51, 8276 (1995).

Zaag, P. J. V. D. et al. Difference between blocking and Néel temperatures in the exchange biased Fe3O4/CoO System. Phys. Rev. Lett. 84, 6102 (2000).

Lierop, J. V., Lin, K.-W., Guo, J.-Y., Ouyang, H. & Southern, B. W. Proximity effects in an exchange-biased Ni80Fe20/Co3O4 thin film. Phys. Rev. B 75, 134409 (2007).

Lenz, K., Zander, S. & Kuch, W. Magnetic proximity effects in antiferromagnet/ferromagnet bilayers: The impact on the Néel temperature. Phys. Rev. Lett. 98, 237201 (2007).

Scholl, A., Liberati, M., Arenholz, E., Ohldag, H. & Stöhr, J. Creation of an antiferromagnetic exchange spring, Phys. Rev. Lett. 92, 247201 (2004).

Li, J. et al. Chirality switching and winding or unwinding of the antiferromagnetic NiO domain Walls in Fe/NiO/Fe/CoO/Ag(001). Phys. Rev. Lett. 113, 147207 (2014).

Takano, M., Terashima, T., Bando, Y. & Ikeda, H. Neutron diffraction study of artificial CoO/NiO superlattices. Appl. Phys. Lett. 51, 205 (1987).

Carey, M. J., Berkowitz, A. E., Borchers, J. A. & Erwin, R. W. Strong interlayer coupling in CoO/NiO antiferromagnetic superlattices. Phys. Rev. B 47, 9952 (1993).

Borchers, J. A. et al. Spatially modulated antiferromagnetic order in CoO/NiO Superlattices. Phys. Rev. Lett. 70, 1878 (1993).

Abarra, E. N., Takano, K., Hellman, F. & Berkowitz, A. E. Thermodynamic measurements of magnetic ordering in antiferromagnetic superlattices. Phys. Rev. Lett. 77, 3451 (1996).

Ramos, C. A., Lederman, D., King, A. R. & Jaccarino, V. New antiferromagnetic insulator superlattices: structural and magnetic characterization of (FeF2)m(CoF2)n. Phys. Rev. Lett. 65, 2913 (1990).

Carrigo, A. S. & Camley, R. E. Phase transitions in antiferromagnetic superlattices. Phys. Rev. B 45, 13117 (1992).

Zhu, J. et al. Antiferromagnetic spin reorientation transition in epitaxial NiO/CoO/MgO(001) systems. Phys. Rev. B 90, 054403 (2014).

Kim, W. et al. Effect of NiO spin orientation on the magnetic anisotropy of the Fe film in epitaxially grown Fe/NiO/Ag(001) and Fe/NiO/MgO(001). Phys. Rev. B 81, 174416 (2010).

Csiszar, S. I. et al. Controlling orbital moment and spin orientation in CoO layers by strain. Phys. Rev. Lett. 95, 187205 (2005).

Zhu, J. et al. Strain-modulated antiferromagnetic spin orientation and exchange coupling in Fe/CoO(001). J. Appl. Phys. 115, 193903 (2014).

Alders, D. et al. Temperature and thickness dependence of magnetic moments in NiO epitaxial films. Phys. Rev. B 57, 11623 (1998).

Arenholz, E., Laan, G. V. D., Chopdekar, R. V. & Suzuki, Y. Angle-dependent Ni2+ x-ray magnetic linear dichroism: interfacial coupling revisited. Phys. Rev. Lett. 98, 197201 (2007).

Wu, Y. Z. et al. Analysis of x-ray linear dichroism spectra for NiO thin films grown on vicinal Ag(001). Phys. Rev. B 78, 064413 (2008).

Laan, G. V. D., Arenholz, E., Chopdekar, R. V. & Suzuki, Y. Influence of crystal field on anisotropic x-ray magnetic linear dichroism at the Co2+L2,3 edges. Phys. Rev. B 77, 064407 (2008).

Schulthess, T. C. & Butler, W. H. Consequences of spin-flop coupling in exchange biased films. Phys. Rev. Lett. 81, 4516 (1998).

Schrön, A. et al. Crystalline and magnetic anisotropy of the 3d-transition metal monoxides MnO, FeO, CoO, and NiO, Phys. Rev. B 86, 115134 (2014).

Haverkort, M. W. et al. Magnetic versus crystal-field linear dichroism in NiO thin films. Phys. Rev. B 69, 020408(R) (2004).

Nakajima, R., Stöhr, J. & Idzerda, Y. U. Electron-yield saturation effects in L-edge x-ray magnetic circular dichroism spectra of Fe, Co, and Ni, Phys. Rev. B 59, 6421 (1999).

Macke, S. & Goering, E. Magnetic reflectometry of heterostructures, J. Phys.: Condens. Matter 26, 363201 (2014).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Key Basic Research Program of China (Grants No. 2015CB921401 and No. 3172011CB921801), the National Science Foundation of China (Grants No. 11274074, No. 11434003, and No. 11474066), and a National Research Foundation of Korea Grant funded by the Korean Government (Grant No. 2012R1A1A2007524).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

W.Y.Z. designed the experiments. L.Q. and D.Z. prepared the sample. L.Q., L.J.H., L.Y.M. and D.Z. carried out the XMLD measurement helped by H.Z., H.C.Y., L.H.-J., P.T.W., L.Q. and G.T. performed the MOKE measurement. K.S.P. and W.C. made the simulation program and L.Q. did the simulation. W.Y.Z. and L.Q. analyzed the results. L.Q. and W.Y.Z. wrote the paper and all the co-authors commented on it.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Li, Q., Liang, J., Luo, Y. et al. Antiferromagnetic proximity effect in epitaxial CoO/NiO/MgO(001) systems. Sci Rep 6, 22355 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep22355

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/srep22355

This article is cited by

-

Tunable magnetic anisotropy of antiferromagnetic NiO in (Fe)/NiO/MgO/Cr/MgO(001) epitaxial multilayers

Scientific Reports (2023)

-

Tuning the Néel temperature in an antiferromagnet: the case of NixCo1−xO microstructures

Scientific Reports (2019)

-

Structural Confinement Assisted a Robust Superparamagnetic State in MgNi2O3 and MgNi1.5Co0.5O3 Nanoparticles at Room Temperature

Journal of Superconductivity and Novel Magnetism (2018)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.

and

and  as a function of NiO thickness at 78 K. Difference in (b) CoO L3 ratio and (d) NiO L2 ratio as a function of NiO thickness at 80 K, 300 K, and 400 K. The green line in (d) was calculated based on Monte Carlo simulation results.

as a function of NiO thickness at 78 K. Difference in (b) CoO L3 ratio and (d) NiO L2 ratio as a function of NiO thickness at 80 K, 300 K, and 400 K. The green line in (d) was calculated based on Monte Carlo simulation results.

and (d–f) NiO L2 ratio difference

and (d–f) NiO L2 ratio difference  for the systems CoO/MgO(001), NiO/MgO(001), and CoO/NiO/MgO(001) with layer thicknesses indicated on the top of each panel. Arrows indicate the AFM ordering temperature TN.

for the systems CoO/MgO(001), NiO/MgO(001), and CoO/NiO/MgO(001) with layer thicknesses indicated on the top of each panel. Arrows indicate the AFM ordering temperature TN.