Abstract

Developing efficient framework for quantum measurements is of essential importance to quantum science and technology. In this work, for the important superconducting circuit-QED setup, we present a rigorous and analytic solution for the effective quantum trajectory equation (QTE) after polaron transformation and converted to the form of Stratonovich calculus. We find that the solution is a generalization of the elegant quantum Bayesian approach developed in arXiv:1111.4016 by Korotokov and currently applied to circuit-QED measurements. The new result improves both the diagonal and off-diagonal elements of the qubit density matrix, via amending the distribution probabilities of the output currents and several important phase factors. Compared to numerical integration of the QTE, the resultant quantum Bayesian rule promises higher efficiency to update the measured state and allows more efficient and analytical studies for some interesting problems such as quantum weak values, past quantum state and quantum state smoothing. The method of this work opens also a new way to obtain quantum Bayesian formulas for other systems and in more complicated cases.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Continuous quantum weak measurement, which stretches the “process” of the Copenhagen’s instantaneous projective measurement, offers special opportunities to control and steer quantum state1,2. This type of measurement is essentially a process of real-time monitoring of environment with stochastic measurement records and causing back-action onto the measured state. However, remarkably, the stochastic change of the measured state can be faithfully tracked. Because of this unique feature, quantum continuous weak measurement can be used, for instance, for quantum feedback of error correction and state stabilization, generating pre- and post-selected (PPS) quantum ensembles to improve quantum state preparation, smoothing and high-fidelity readout and developing novel schemes of quantum metrology1,2.

On the other aspect, the superconducting circuit quantum electrodynamics (cQED) system3,4,5 is currently an important platform for quantum measurement and control studies6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15. In particular, the continuous weak measurements in this system, as schematically shown in Fig. 1(a), have been demonstrated in experiments12,13,14, together with feedback control15.

Qubit measurement in circuit QED and the idea of one-step Bayesian state inference.

(a) Schematic plot for the circuit QED setup and measurement principle of qubit states via measuring the quadrature of the cavity field. The superconducting qubit couples dispersively to the cavity through Hamiltonian χa†aσz which, under the interplay of cavity driving and damping, forms cavity fields α1(t) and α2(t) corresponding to qubit states  and

and  . The leaked photon (with rate κ) is detected using the homodyne technique by mixing it with a local oscillator (LO). (b) Illustrative explanation for the advantage of the one-step Bayesian rule (BR) over the continuous (multi-step) integration of the quantum trajectory equation (QTE). That is, using the known functions α1,2(t) and the detected current I(t) of the homodyne measurement, the BR allows a one-step inference for the qubit state.

. The leaked photon (with rate κ) is detected using the homodyne technique by mixing it with a local oscillator (LO). (b) Illustrative explanation for the advantage of the one-step Bayesian rule (BR) over the continuous (multi-step) integration of the quantum trajectory equation (QTE). That is, using the known functions α1,2(t) and the detected current I(t) of the homodyne measurement, the BR allows a one-step inference for the qubit state.

For continuous weak measurements, the most celebrated formulation is the quantum trajectory equation (QTE) theory, which has been broadly applied in quantum optics and quantum control studies1,2. However, in some cases of real experiment, numerical integration of the QTE is not efficient and alternatively, the one-step quantum Bayesian approach has been employed to update the quantum state based on the integrated output currents12,13,14,15, as illustrated in Fig. 1(b). Meanwhile, one may notice that the Bayes’ formula is the fundamental tool for classical noisy measurements2. In this work we carry out the analytic and exact solution of the effective QTE of the cQED system. Desirably, we find that the solution is a generalization of the elegant quantum Bayesian approach developed in ref. 16 by Korotokov and currently applied to circuit-QED experiments13,14,15. The new result is not bounded by the “bad”-cavity and weak-response limits as in ref. 16 and promises higher efficiency than numerically integrating the QTE. The Bayesian rule also allows more efficient and analytical studies for some interesting problems such as quantum weak values17,18, past quantum state19,20,21 and quantum state smoothing22,23, etc.

Results

Exact Bayesian rule for cQED measurement

We consider the cQED architecture consisting of a superconducting transmon qubit dispersively coupled to a waveguide cavity, see Fig. 1(a). The qubit-cavity interaction is given by the Hamiltonian3,4,5, Hint = χa†aσz, where χ is the dispersive coupling rate, a† and a are respectively the creation and annihilation operators of the cavity mode and σz is the qubit Pauli operator. This interaction Hamiltonian characterizes a qubit-state-dependent frequency shift of the cavity which is used to perform quantum state measurement. After a qubit-state-dependent displacement transformation (called also “polaron” transformation) to eliminate the cavity degrees of freedom24, the single quadrature homodyne current can be reexpressed as

In this result, ξ(t), originated from the fundamental quantum-jumps, is a Gaussian white noise and satisfies the ensemble-average properties of E[ξ(t)] = 0 and E[ξ(t)ξ(t′)] = δ(t − t′). Γci(t) is the coherent information gain rate which, together with the other two, say, the no-information back-action rate Γba(t) and the overall measurement decoherence rate Γd(t), is given by24

Here we have denoted the local oscillator’s (LO) phase in the homodyne measurement by φ, the cavity photon leaky rate by κ and  with α1(t) and α2(t) the cavity fields associated with the respective qubit states

with α1(t) and α2(t) the cavity fields associated with the respective qubit states  and

and  .

.

In this work, for brevity, we directly quote the transformed QTE results from ref. 24 where the derivation and explanation of the above rates can be found with details. Briefly speaking, the coherent information gain rate, Γci, describes the backaction of information gain during the measurement, which corresponds to the “spooky” backaction rate termed in ref. 16 by Korotkov. Γba, corresponding to the “realistic” backaction rate in ref. 16, characterizes the backaction of the measurement device not associated with information gain of the qubit state. And the overall decoherence rate, Γd, describes the ensemble average effect of the measurement on the qubit state, over large number of quantum trajectories.

Within the framework of “polaron” transformation, the effective quantum trajectory equation (QTE) for qubit state alone can be expressed as24

for the diagonal and off-diagonal elements of the density matrix, respectively. Here we have also absorbed a generalized dynamic ac-Stark shift,  into the effective frequency of the qubit,

into the effective frequency of the qubit,  .

.

Eqs.(5) and (6) are defined on the basis of Itó calculus and is the form for numerical simulations25,26. However, as to be clear in the following, in order to get the correct result of the quantum Bayesian rule, one needs to convert it into the Stratonovich-type form. We thus have

We see that, compared to the Itó type Eqs. (5) and (6), the Gaussian noise ξ(t) in all the noisy terms has been replaced now by the homodyne current I(t) which is given by Eq. (1).

Now we are ready to integrate Eqs. (7) and (8). For the first equation of ρ11(t), perform  on both sides. Noting that

on both sides. Noting that  , we obtain

, we obtain  , where

, where  . In deriving, we have used the property ρ11 + ρ22 = 1. Using this property again, we may split the solution into two equations

. In deriving, we have used the property ρ11 + ρ22 = 1. Using this property again, we may split the solution into two equations

where  . Further, integrating the second equation for ρ12(t), we obtain

. Further, integrating the second equation for ρ12(t), we obtain

In this solution, we introduced the measurement rate Γm = Γba + Γci; and all the factors except the last one have been in explicit forms of integration with known integrands. For the last factor, since  , substituting the explicit solution of ρ11(t) to complete the integration yields

, substituting the explicit solution of ρ11(t) to complete the integration yields

Then we reexpress the solution of the off-diagonal element ρ12(tm) in a compact form as

where we have introduced

Desirably, these factors recover those proposed in ref. 27 from different insight and analysis. As demonstrated in ref. 27, these factors have important effects to correct the “bare” Bayesian rule for the off-diagonal elements. As to be seen soon (after simple algebra), the above treatment provides also a reliable method allowing us to obtain new and precise expressions for the prior distribution knowledge of the output currents which are of essential importance to the Bayesian inference for the cQED measurement.

To make the results derived above in the standard form of Bayesian rule, let us rewrite  and

and  , where N(tm) = ρ11(0)P1(tm) + ρ22(0)P2(tm) and the current distribution probabilities read

, where N(tm) = ρ11(0)P1(tm) + ρ22(0)P2(tm) and the current distribution probabilities read

where  and

and  and V = 1/tm characterizes the distribution variance. For Bayesian inference, the “prior” knowledge of the distribution probabilities P1(2)(tm) associated with qubit state

and V = 1/tm characterizes the distribution variance. For Bayesian inference, the “prior” knowledge of the distribution probabilities P1(2)(tm) associated with qubit state

, should be known in advance. Then, one utilizes them to update the measured state based on the collected output currents, using the following exact quantum Bayesian rule. First, for the off-diagonal element,

, should be known in advance. Then, one utilizes them to update the measured state based on the collected output currents, using the following exact quantum Bayesian rule. First, for the off-diagonal element,

Second, for the diagonal elements,

where j = 1, 2. The results of Eq. (14)–(19), constitute the main contribution of this work.

Result of simpler case

The original work of quantum Bayesian approach considered a charge qubit  measured by point-contact detector28. This problem can be described by the following QTE which has been applied broadly in quantum optics1,2

measured by point-contact detector28. This problem can be described by the following QTE which has been applied broadly in quantum optics1,2

In this equation the Lindblad term takes D[σz]ρ = σzρσz − ρ and the information-gain backaction term reads H[σz]ρ = σzρ + ρσz − 2Tr[σzρ]ρ. γ′ and γ are respectively the measurement decoherence and information-gain rates (constants). And, this equation is conditioned on the measurement current  , since both share the same stochastic noise ξ(t).

, since both share the same stochastic noise ξ(t).

Following precisely the same procedures of solving the above cQED system, one can arrive to similar results as Eqs. (9)(10) and (13) with, however, simpler X(tm) which is now given by  , owing to the constant γ. Also, now the dephasing factor simply reads

, owing to the constant γ. Also, now the dephasing factor simply reads  where

where  . For this simpler setup, the phase factor Φ1 takes the trivial result Φ1(tm) = ωqtm and the factor Φ2 vanishes. The simpler result of X(tm) allows us to introduce, from the factors

. For this simpler setup, the phase factor Φ1 takes the trivial result Φ1(tm) = ωqtm and the factor Φ2 vanishes. The simpler result of X(tm) allows us to introduce, from the factors  in Eqs. (9)(10) and (13), the distribution probabilities of the standard Gaussian form

in Eqs. (9)(10) and (13), the distribution probabilities of the standard Gaussian form

where  and

and  . With these identifications, one recovers the quantum Bayesian rule proposed by Korotkov in ref. 28.

. With these identifications, one recovers the quantum Bayesian rule proposed by Korotkov in ref. 28.

Similarly, for the cQED setup, from  , simple experience likely tells us that, corresponding to the qubit states

, simple experience likely tells us that, corresponding to the qubit states  and

and  , the stochastic current Im (average of the stochastic I(t) over tm) should be respectively centered at

, the stochastic current Im (average of the stochastic I(t) over tm) should be respectively centered at  , in terms of the Gaussian distribution as given by Eq. (21). However, out of our expectation, this is not true. Below we display numerical results to show the exactness of the Bayesian rule Eqs. (18) and (19) when associated with (16), rather than with the Gaussian formula (20).

, in terms of the Gaussian distribution as given by Eq. (21). However, out of our expectation, this is not true. Below we display numerical results to show the exactness of the Bayesian rule Eqs. (18) and (19) when associated with (16), rather than with the Gaussian formula (20).

Numerical results

To implement the above exact Bayesian rule for state inference in practice, we should carry out in advance the rates Γci(t), Γba(t), Γd(t) and as well the ac-Stark shift B(t). From the expressions of these quantities, we know that the key knowledge required is the coherent-state parameters α1(t) and α2(t) which are, respectively, the consequence of the interplay of external driving and cavity damping for qubit states  and

and  , satisfying

, satisfying  , where

, where  . The simple analytic solutions read

. The simple analytic solutions read

In this solution,  are the steady-state cavity fields; and α0 is the initial cavity field before measurement which is zero if we start with a vacuum.

are the steady-state cavity fields; and α0 is the initial cavity field before measurement which is zero if we start with a vacuum.

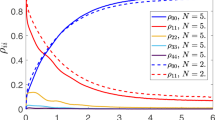

In Fig. 2, taking a specific trajectory for each case as an example, we compare the results from different approaches. In this plot we adopt a reduced system of units by scaling energy and frequency with the microwave drive strength (εm). We have assumed two types of parameters in the simulation: for the upper row (weaker response) we assumed χ = 0.1 while for the lower one (stronger response) we assumed χ = 0.5, both violating the joint condition of “bad”-cavity and weak-response since we commonly used κ = 2. (Other parameters are referred to the figure caption). The basic requirement of the “bad”-cavity and weak response limits is κ ≫ χ. This has a couple of consequences: (i) The time-dependent factor in Eq. (22), e±iχte−κt/2, would become less important so that we can neglect the transient dynamics of the cavity field and all the rates (Γd, Γba and Γci) can be treated as (steady state) constants16. (ii) It makes the measurement rate (Γm) much smaller than κ and the purity factor D(tm) almost unity. This means that, with respect to the cavity photon’s leakage, the (gradual collapse) measurement process is slow and the qubit state remains almost pure in the ideal case (in the absence of photon loss and amplification noise). One can check that the parameters used in Fig. 2 (especially the case χ = 0.5) violate these criteria.

Accuracy demonstration of the Bayesian rule against the quantum trajectory equation.

(a,d) Stochastic currents in the homodyne detection for dispersive coupling χ = 0.1 and 0.5. The black curves denote the coarse-grained results for visual purpose, while the original currents (blue ones) are actually used for state estimate (inference). (b,c) State (density matrix) evolution under continuous measurement for a relatively weak qubit-cavity coupling, χ = 0.1. (e,f) State evolution under continuous measurement for a strong qubit-cavity coupling, χ = 0.5. (b,c,e,f) The curves “E” (red), “G” (green) and “K” (blue) denote, respectively, our exact Bayesian rule, Eqs. (18) and (19) together with (17), the approximate one involving instead the usual Gaussian distribution of Eq. (21) and that proposed by Korotkov16 under the bad-cavity and weak-response limits. In each figure, the lower panel plots also the difference from the quantum trajectory equation result, indicating that the BR proposed in this work is indeed exact. In all these numerical simulations, we chose the LO’s phase φ = π/4 and adopted a system of reduced units with parameters Δr = 0, εm = 1.0 and κ = 2.0.

We find that for both cases the results from our exact Bayesian rule, Eqs. (18) and (19) together with (16), precisely coincides with those from simulating the QTE. As a comparison, in Fig. 2 we plot also the results from other two approximate Bayesian approaches. One is the Bayesian approach constructed by Korotkov in ref. 16 under the bad-cavity and weak-response limits, which is labeled in Fig. 2 by “K”. Another is the Bayesian rule obtained in ref. 27, which holds the same factors as shown in Eqs. (14)–(16), but involves the usual Gaussian distribution of the type of Eq. (21). The results are labeled by “G” in Fig. 2. We find from this plot that, for the modest violation of the bad-cavity and weak-response limits, the “G” results are better than the “K” ones. However, for strong violation, the “G” results will become unreliable as well. In contrast, as we observe here and have checked for many more trajectories in the case of violating the bad-cavity and weak-response limits, the exact Bayesian rule can always work precisely while both the “K” and “G” approaches failed.

Discussion

To summarize, for continuous weak measurements in circuit-QED, we carry out the analytic and exact solution of the effective QTE which generalizes the quantum Bayesian approach developed in ref. 16 and applied in circuit-QED experiments13,14,15. The new result is not bounded by the “bad”-cavity and weak-response limits as in ref. 16 and improves the quantum Bayesian rule via amending the distribution probabilities of the output currents and several important phase factors16,27.

The efficiency of quantum Bayesian approach can be understood with the illustrative Fig. 1. Instead of the successive step-by-step state estimations (over many infinitesimal time intervals of dt) using QTE, the Bayesian rule offers the great advantage of one-step estimation, with a major job by inserting the continuous measurement outcomes (currents) into the simple expressions of the prior knowledge P1,2(tm) given by Eq. (17) and the phase correction factor Φ2(tm). Other α1,2(t)-dependent factors are independent of the measurement outcomes and can be carried out in advance. The time integration in P1,2(tm) and Φ2(tm) can be completed as soon as the continuous measurement over (0, tm) is finished. Therefore, the state estimation can be accomplished using Eqs. (18) and (19), with similar efficiency as using the usual simple Gaussian distribution Eq. (21).

In this work we have focused on the single quadrature measurement. For the so-called (I, Q) two quadrature measurement, following the same procedures of this work or even simply based on the characteristic structure of the final results, Eqs. (14)–(19), one can obtain the associated quantum Bayesian rule as well16,27.

We finally remark that, just as Bayesian formalism is the central theory for noisy measurements in classical control and information processing problems, quantum Bayesian approach can be taken as an efficient theoretical framework for continuous quantum weak measurements. Compared to the “construction” method16, the present work provides a direct and more reliable route to formulate the quantum Bayesian rule. Applying similar method to more complicated cases such as joint measurement of multiple qubits or to other systems is of interest for further studies.

Methods

Circuit-QED setup and measurements

Under reasonable approximations, the circuit-QED system resembles the conventional atomic cavity-QED system which has been extensively studied in quantum optics. Both can be well described by the Jaynes-Cummings Hamiltonian. In dispersive regime3,4,5, i.e., the detuning between the cavity frequency (ωr) and qubit energy (ωq), Δ = ωr − ωq, being much larger than the coupling strength g, the system Hamiltonian (in the rotating frame with the microwave driving frequency ωm) reads3,4,5

where Δr = ωr − ωm and  , with χ = g2/Δ the dispersive shift of the qubit energy. In Eq. (23), a† (a) and σz are respectively the creation (annihilation) operator of cavity photon and the quasi-spin operator (Pauli matrix) for the qubit. εm is the microwave drive amplitude for continuous measurements. For single-quadrature (with reference local oscillator phase φ) homodyne detection of the cavity photons, the measurement output can be expressed as

, with χ = g2/Δ the dispersive shift of the qubit energy. In Eq. (23), a† (a) and σz are respectively the creation (annihilation) operator of cavity photon and the quasi-spin operator (Pauli matrix) for the qubit. εm is the microwave drive amplitude for continuous measurements. For single-quadrature (with reference local oscillator phase φ) homodyne detection of the cavity photons, the measurement output can be expressed as  . After eliminating the cavity degrees of freedom via the “polaron”-transformation, this output current turns to Eq. (1). Moreover, the conditional qubit-cavity joint state ρ(t), which originally satisfies the standard optical quantum trajectory equation1,2, becomes now after eliminating the cavity states24:

. After eliminating the cavity degrees of freedom via the “polaron”-transformation, this output current turns to Eq. (1). Moreover, the conditional qubit-cavity joint state ρ(t), which originally satisfies the standard optical quantum trajectory equation1,2, becomes now after eliminating the cavity states24:

In addition to the Lindblad term (the second one on the r.h.s), the other superoperator is introduced through  , where 〈σz〉 = Tr[σzρ]. In this result, B(t) is the dynamic ac-Stark shift and Γd, Γci and Γba are, respectively, the overall measurement decoherence, information gain and no-information back-action rates (with explicit expressions given by Eqs. (2)–(4). In the qubit-state basis, Eq. (24) gives Eqs. (5) and (6).

, where 〈σz〉 = Tr[σzρ]. In this result, B(t) is the dynamic ac-Stark shift and Γd, Γci and Γba are, respectively, the overall measurement decoherence, information gain and no-information back-action rates (with explicit expressions given by Eqs. (2)–(4). In the qubit-state basis, Eq. (24) gives Eqs. (5) and (6).

Conversion rule

In order to convert Eqs. (5) and (6) to Eqs. (7) and (8), in this Appendix we specify the conversion rule from Itó to Stratonovich stochastic equations25,26. Suppose for instance we have a set of Itó-type stochastic equations

with j = 1, 2, ···, K. The corresponding Stratonovich-type equations read

Comparing Eq. (25) with Eqs.(5) and (6), we identify Y1 = ρ11 and Y2 = ρ12. Then we have  and

and  . Applying the conversion rule Eq. (26), one can convert Eqs. (5) and (6) to Eqs. (7) and (8) by completing the following algebraic manipulations:

. Applying the conversion rule Eq. (26), one can convert Eqs. (5) and (6) to Eqs. (7) and (8) by completing the following algebraic manipulations:

and

In the above manipulations, we have used 〈σz〉 = ρ11 − ρ22 = 2ρ11 − 1, 1 − 〈σz〉2 = 4ρ11ρ22 and Γm = Γci + Γba.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Feng, W. et al. Exact quantum Bayesian rule for qubit measurements in circuit QED. Sci. Rep. 6, 20492; doi: 10.1038/srep20492 (2016).

References

Wiseman, H. M. & Milburn, G. J. Quantum Measurement and Control (Cambridge Univ. Press, Cambridge, 2009).

Jacobs, K. Quantum Measurement Theory and Its Applications (Cambridge Univ. Press, Cambridge, 2014).

Blais, A. et al. Cavity quantum electrodynamics for superconducting electrical circuits: An architecture for quantum computation. Phys. Rev. A 69, 062320 (2004).

Wallraff, A. et al. Strong coupling of a single photon to a superconducting qubit using circuit quantum electrodynamics. Nature (London) 431, 162 (2004).

Chiorescu, I. et al. Coherent dynamics of a flux qubit coupled to a harmonic oscillator. Nature (London) 431, 159 (2004).

Schoelkopf, R. J. & Girvin, S. M. Wiring up quantum systems. Nature 451, 664 (2008).

Palacios-Laloy, A. et al. Experimental violation of a Bell’s inequality in time with weak measurement. Nat. Phys. 6, 442 (2010).

Groen, J. P. et al. Partial-measurement back-action and non-classical weak values in a superconducting circuit. Phys. Rev. Lett. 111, 090506 (2013).

Mariantoni, M. et al. Photon shell game in three-resonator circuit quantum electrodynamics. Nat. Phys. 7, 287 (2011).

Campagne-Ibarcq, P. et al. Persistent control of a superconducting qubit by stroboscopic measurement feedback. Phys. Rev. X 3, 021008 (2013).

Risté, D. et al. Initialization by Measurement of a Superconducting Quantum Bit Circuit. Phys. Rev. Lett. 109, 050507 (2012).

Hatridge, M. et al. Quantum Back-Action of an Individual Variable-Strength Measurement. Science 339, 178 (2013).

Murch, K. W., Weber, S. J., Macklin, C. & Siddiqi, I. Observing single quantum trajectories of a superconducting quantum bit. Nature 502, 211 (2013).

Tan, D., Weber, S. J., Siddiqi, I., Molmer, K. & Murch, K. W. Prediction and Retrodiction for a Continuously Monitored Superconducting Qubit. Phys. Rev. Lett. 114, 090403 (2015).

Vijay, R. et al. Stabilizing Rabi oscillations in a superconducting qubit using quantum feedback. Nature 490, 77 (2012).

Korotkov, A. N. Quantum Bayesian approach to circuit QED measurement. arXiv:1111.4016 (2011).

Williams, N. S. & Jordan, A. N. Weak values and the Leggett-Garg inequality in solid-state qubits. Phys. Rev. Lett. 100, 026804 (2008).

Qin, L., Liang, P. & Li, X. Q. Weak values in continuous weak measurement of qubits. Phys. Rev. A 92, 012119 (2015).

Gammelmark, S., Julsgaard, B. & Molmer, K. Past Quantum States of a Monitored System. Phys. Rev. Lett. 111, 160401 (2013).

Tan, D., Weber, S. J., Siddiqi, I., Molmer, K. & Murch, K. W. Prediction and Retrodiction for a Continuously Monitored Superconducting Qubit. Phys. Rev. Lett. 114, 090403 (2015).

Rybarczyk, T. et al. Past quantum state analysis of the photon number evolution in a cavity. arXiv:1409.0958 (2014).

Tsang, M. Optimal waveform estimation for classical and quantum systems via time-symmetric smoothing. Phys. Rev. A 80, 033840 (2009).

Guevara, I. & Wiseman, H. Quantum State Smoothing. arXiv:1503.02799v2 (2015).

Gambetta, J. et al. Quantum trajectory approach to circuit QED: Quantum jumps and the Zeno effect. Phys. Rev. A 77, 012112 (2008).

Kloeden, P. E. & Platen, E. Numerical Solution of Stochastic Differential Equations (Springer-Verlag, Berlin, 1992).

Goan, H. S., Milburn, G. J., Wiseman, H. M. & Sun, H. B. Continuous quantum measurement of two coupled quantum dots using a point contact: A quantum trajectory approach. Phys. Rev. B 63, 125326 (2001).

Wang, P., Qin, L. & Li, X. Q. Quantum Bayesian rule for weak measurements of qubits in superconducting circuit QED. New J. Phys. 16, 123047 (2014); Corrigendum: Quantum Bayesian rule for weak measurements of qubits in superconducting circuit QED. ibid.17, 059501 (2015).

Korotkov, A. N. Continuous quantum measurement of a double dot. Phys. Rev. B 60, 5737 (1999).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the NNSF of China under grants No. 101202101 & 10874176 and the State “973” Project under grants No. 2011CB808502 & 2012CB932704.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

X.Q.L. supervised the work; W.F., P.F.L. and L.P.Q. carried out the calculations; X.Q.L. wrote the paper and all authors reviewed it. W.F. and P.F.L. equally contributed to this work.

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Feng, W., Liang, P., Qin, L. et al. Exact quantum Bayesian rule for qubit measurements in circuit QED. Sci Rep 6, 20492 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep20492

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/srep20492

This article is cited by

-

Quantum parameter estimation via dispersive measurement in circuit QED

Quantum Information Processing (2018)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.