Abstract

Using molecular dynamics simulations, we have studied the atomic correlations characterizing the second peak in the radial distribution function (RDF) of metallic glasses and liquids. The analysis was conducted from the perspective of different connection schemes of atomic packing motifs, based on the number of shared atoms between two linked coordination polyhedra. The results demonstrate that the cluster connections by face-sharing, specifically with three common atoms, are most favored when transitioning from the liquid to glassy state and exhibit the stiffest elastic response during shear deformation. These properties of the connections and the resultant atomic correlations are generally the same for different types of packing motifs in different alloys. Splitting of the second RDF peak was observed for the inherent structure of the equilibrium liquid, originating solely from cluster connections; this trait can then be inherited in the metallic glass formed via subsequent quenching of the parent liquid through the glass transition, in the absence of any additional type of local structural order. Increasing ordering and cluster connection during cooling, however, may tune the position and intensity of the split peaks.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Metallic glasses (MGs) were first discovered some five decades ago but are still of significant current interest because of their unique structure and properties1,2,3,4. Indeed, many fundamental materials science issues remain unresolved for MGs, as well as for supercooled liquids (SLs) which are their parent phase above the glass transition temperature1,2,3,4,5,6. However, compared to crystalline materials, the lack of long-range translational order presents inherent challenges to characterizing the atomic-level structure and to discerning the salient structure-property relationships in amorphous alloys7,8. These issues involving the atomic-level structure in MGs and SLs have been under extensive study in recent years7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15. Notably, their short-range order (SRO) has been characterized in terms of atomic packing motifs. These motifs are the common coordination polyhedra in each MG (each coordination polyhedron is for an atom at center with surrounding nearest neighbors, NNs). For example, some MGs are characterized by full icosahedra as the dominant motif, which are coordination polyhedra with Voronoi index <0, 0, 12, 0> and five-fold bonds only. In these alloys a variety of thermodynamic, kinetic and mechanical properties have been correlated with the degree of icosahedral SRO16,17,18,19. In general, the SRO has a diverse range in terms of the preferable motifs, as summarized for different MGs in Refs. 7 and 8.

At length scales longer than that typically described by this SRO, i.e., beyond the first NNs corresponding to the first peak in the radial distribution function (RDF), characterizing the atomic structure of these materials becomes even more complex9,10,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30. For example, efficient packing of quasi-equivalent “clusters”9,10 (the motifs) has been proposed, where the packing of the polyhedra in three-dimensional space is pictured to follow an icosahedral or face-centered cubic (F.C.C) pattern. There is also the notion of possible self-similar packing of atomic clusters with the characteristics of a fractal network of dimension 2.31 or 2.5020,21. Additionally, the concept of spherical-periodic order, derived from the resonance between static order and the electronic system, was modified to involve additional local crystal-like translational symmetry to describe atomic order up to the long-range scale22,23,24,27. However, before one can establish the nature of extended order (such as those postulated in these models, which most likely vary from one alloy system to another), a useful step is to first understand the atomic correlations with atoms in the second nearest neighbor shell. These latter correlations are reflected by the second peak in the RDFs of MGs and their parent SLs. As the distances characteristic of the second peak are just beyond the short-range scale, i.e., the packing of atoms in the NN shell constituting the motif/cluster above, the second-NN correlations can be a useful starting point for the characterization of medium-range order.

A commonly used method to illustrate how one atom correlates with atoms in its second nearest-neighbor shell is using an analysis of connection schemes of the coordination polyhedra, where previous work has shown that the coordination polyhedra can connect with each other by sharing one, two, three or four atoms31,32,33,34,35,36. As such, the pair correlations giving rise to the second peak and its splitting in many observations, may have a universal origin in the specific ways each motif can connect with the next, see for example, Ref. 35. The purpose of this article is to perform a systematic analysis of such connection schemes across a broader range of MG systems than has been considered previously. We will address questions including: (i) do cluster connection schemes vary across different MG systems with differing compositions and SRO (NN packing motifs); ii) how cluster connection schemes evolve as a function of temperature during cooling, in particular the difference between the liquid state and the glass; (iii) can the various connection schemes account for the split second RDF peak, across systems with differing packing motifs and for the same system in the MG versus SL state; and (iv) how the different cluster connection schemes affect mechanical performance, i.e., which cluster connections are stiffer or more flexible.

To address these issues, we have conducted a systematic study using molecular dynamics (MD) simulations37 of a number of representative model metallic-glass systems with different constituents and prepared at different cooling rates (see Methods). These systems were modeled by embedded-atom-method potentials optimized for the following MG systems: Cu64Zr36, Ni80P20, Al90La10, Mg65Cu25Y10 and Zr46Cu46Al834,38,39 (Table 1). The SRO motifs in these samples have been characterized before: the topological packing of NN atoms (i.e., within the first peak of the RDF) has been well documented7.

Results and Discussions

General properties of polyhedra connections

To illustrate how the second-NN pair correlation distance is related to the cluster connection, Fig. 1(a) shows schematically two representative atoms that are second nearest neighbors. Each of these two atoms is of course the center of its own coordination polyhedron (cluster)31,32,33,34,35,36. The two clusters are represented by the two color-shaded regions in Fig. 1(a). They are connected together, by the atoms at the locations where the two clusters overlap (the shared atoms). For any arbitrary reference atom, its second NN shell can be pictured as composed of atoms each at the center of a cluster connected to that of the reference atom (see the example depicted in the inset in Fig. 1(a)). For all the atoms in the second NN shell, their spatial correlations with the reference atom superimpose into the second peak in the RDF, g(r), as indicated in Fig. 1(a).

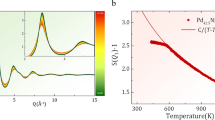

(a) Radial distribution functions g(r) of Ta liquids at 3300 K (orange line) and the inherent structures of Ta liquids at 3300 K (cyan line) as well Ta glass at 300 K (blue dashed line). The inset schematically illustrates the atomic order at the second nearest-neighbor shell as the correlation between two central atoms (as marked), which also corresponds to the second peak in g(r). (b) Shown schematically are four different schemes of coordination polyhedra connections with the number of shared atoms from one to four, which are denoted as 1-atom, 2-atom, 3-atom and 4-atom cluster connections, respectively.

In Fig. 1(a) the RDF shown by the thick solid line is for a Ta equilibrium liquid at 3300 K (following the same simulation procedure in40), while the thinner cyan line reflects the corresponding inherent structure obtained by conjugate-gradient energy minimization (see Methods) to remove the vibrational thermal contributions. The inherent structure of a liquid, with these vibrational contributions excluded, represents the local minimum of the potential energy basin the liquid is in5,6,41 and has been widely utilized to study the liquid structure42,43,44,45. The second peak in g(r) of the inherent structure of Ta liquids is split, similar to the Ta glass (see blue dashed line in Fig. 1(a)) obtained by quenching the same liquid at 1013 K/s to room temperature. Such peak splitting has been observed in numerous amorphous metals and alloys, see for example, refs. 22,25,31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36 and will be discussed in more detail later.

The cluster connection can have multiple possible schemes, as shown schematically in Fig. 1(b). Here the neighboring polyhedra share one, two, three and four atoms, respectively, which are denoted hereafter as 1-atom, 2-atom, 3-atom and 4-atom connections, respectively. The first three categories refer to the connections by sharing a vertex, an edge and a face of polyhedra, while the last category (i.e., 4-atom) refers to sharing distorted quadrilateral or squashed tetrahedra (i.e., with 4 atoms almost in the same plane, but not necessarily forming a perfect quadrangle face). The latter category is different from the previous definition of interpenetrating polyhedra16,34, where the two central atoms inside are nearest neighbor atoms instead of second nearest neighbors, which is the focus of this paper. The cluster connections beyond 4-atom (sharing more than 4 atoms) are neglected due to their very low fraction (e.g., <0.018 per atom in sample #8). Each of these different connection schemes in Fig. 1(b) leads to a different most-probable distance between the two center atoms, thus giving rise to peaks at different correlation distances in the RDF. In other words, for any given MG, the broad second peak in the RDF is a result of the superimposition of the contributions from the four connection schemes and would likely show sub-peaks.

In Fig. 2, the g(r) for Ni80P20 (sample #5) and Zr46Cu46Al8 (sample #8) MGs at 300 K are evaluated up to large atomic separations (20 Å). The red arrows in Fig. 2(a) indicate the splitting of the second peak for Ni80P20, similar to that observed in Fig. 1(a) and in previous experiments and simulations in the literature22,25,31,36. Note that not all MGs exhibit split second peaks, e.g., see the Zr46Cu46Al8 case in Fig. 2(b) and further discussions below.

Radial distribution functions g(r) for (a) Ni80P20 and (b) Zr46Cu46Al8 MGs at 300 K obtained by MD simulation with a cooling rate of 1010 K/s (Samples #5 and 8, respectively, in Table 1).

The decomposed radial distribution functions for nearest-neighbors (NN), second nearest neighbor atoms via 1-atom, 2-atom, 3-atom and 4-atom cluster connections, are also included. The insets show a magnified RDF at large distances.

The decomposed components of the RDFs, specifically for the NN atoms and four cluster connection schemes for atoms in the second-NN shell, can be defined as:

where i and j atoms are linked by α type of connection (NN, or one of the four atomic cluster connection schemes for the second NNs), rij is their interatomic distance; Nα are the number of atoms with α type of connection; V is the volume of the entire sample. For comparison, the decomposed RDF components for each of the connection schemes for Ni80P20 and Zr46Cu46Al8 MGs are also plotted in Fig. 2. These decomposed g(r) curves resemble those reported previously33, but with a stronger intensity for 1-atom and 3-atom and a weaker intensity for 2-atom and 4-atom connections.

From the geometry seen in Fig. 1(b) for cluster connection schemes corresponding to 1-atom, 2-atom, 3-atom and 4-atom, the most-probable distance ( ) between the two second-NN atoms (the centers of the two connected coordination polyhedra) can be calculated to be31

) between the two second-NN atoms (the centers of the two connected coordination polyhedra) can be calculated to be31  , respectively, where R1 is the average bond length. These are therefore the predicted second peak positions from the decomposed g(r). To make a comparison between the MD simulations and these calculated

, respectively, where R1 is the average bond length. These are therefore the predicted second peak positions from the decomposed g(r). To make a comparison between the MD simulations and these calculated  , for each of the four types of cluster connections we evaluated the second-NN distance (peak position), averaged over all the partial RDFs for each MD glass sample, for each species, using:

, for each of the four types of cluster connections we evaluated the second-NN distance (peak position), averaged over all the partial RDFs for each MD glass sample, for each species, using:

The results are plotted in Fig. 3(a), where each data point represents one species for a sample listed in Table 1 and the solid lines represent the  predictions. As can be seen in Fig. 3(a), the MD simulation results closely match the calculated

predictions. As can be seen in Fig. 3(a), the MD simulation results closely match the calculated  . This supports the notion that the atomic cluster connection is primarily responsible for the second-peak locations in the RDF.

. This supports the notion that the atomic cluster connection is primarily responsible for the second-peak locations in the RDF.

(a) The correlation between average bond length R1 and average distance (R2*) of the second nearest-neighbors, for the four cluster connection schemes. Each data point is from each species in the samples listed in Table 1. The solid lines are from a geometric calculation, as described in the text. (b) The average number of connected clusters versus NN coordination number for each species of the studied samples (in Table 1) at their corresponding liquidus temperatures. We calculate R1 and CN for each species, in each sample. For example, Cu in Cu64Zr36 and Zr46Cu46Al8 have different measured R1 and CN and they are all used in Fig. 3.

Another important issue is if and how the cluster connections depend on the nearest-neighbor coordination number (CN). The CN varies with the local SRO, reflecting different atomic size ratio and cluster topological order for each amorphous system. In other words, the packing motif is different from alloy to alloy. This issue is examined in Fig. 3(b), where we plot the average number of cluster connections against the average CN surrounding each species, in various alloys (Table 1) at the corresponding experimental liquidus temperatures (Tl)46. The largest NN coordination number is for La atoms in Al90La10, since La atoms are much larger than Al. Although the experimental value of Tl may not correspond exactly with the liquidus predicted by the EAM potential, we have also tested the temperature range between (Tl − 100) K and (Tl + 100) K and the results in Fig. 3(b) are largely unaffected. Analysis at the liquidus temperatures undertaken here avoids the complexity associated with cluster connection development by structural ordering during cooling through the glass transition (illustrated in detail below in Fig. 4).

(a) The number of connected clusters per atom, N, for four cluster connection schemes (1-atom, 2-atom, 3-atom and 4-atom) at room temperature (T=300 K) for samples #1 to 8 in Table 1. (b) The difference in N for each of the four cluster connection schemes (1-atom, 2-atom, 3-atom and 4-atom) between T = 300 K and the liquidus temperature for sample #1 to 8 in Table 1. The first four samples as marked, are Cu64Zr36 MGs prepared at increasing cooling rates.

We observe that the dependence of 1-atom and 2-atom cluster connections on CN is weak, while the 3-atom and 4-atom cluster connections scale almost linearly with CN (apart from small fluctuations about linear behavior), as seen in Fig. 3(b). In other words, at the liquidus temperature, the larger the coordination number of a central atom, the more 3-atom and 4-atom cluster connections exist, while the number of 1-atom and 2-atom connections remain essentially unchanged. This observation likely results from the closer distance between the first nearest-neighbor shell and 3-atom or 4-atom connected clusters, which implies that the CN (and hence different motif) exerts an influence on the number of the clusters connected. Nevertheless, in all cases the connection schemes and associated characteristic  values are universally the same. This is not surprising; as all the characteristic motifs tend towards polytetrahedral packing inside7,8, for all MGs the cluster connection ultimately is the connection of tetrahedral units.

values are universally the same. This is not surprising; as all the characteristic motifs tend towards polytetrahedral packing inside7,8, for all MGs the cluster connection ultimately is the connection of tetrahedral units.

It should be noted that all the data in Fig. 3(b) were evaluated within equilibrium liquids rather than in the glassy state. The structural ordering during supercooling, especially close to the glass transition, will alter the preference for certain connection schemes, in particular of the 2-atom and 3-atom clusters, as described in the following section; the correlations in Fig. 3(b) in liquids will therefore not be necessarily the same for the glassy state. More discussion of the difference follows in the next section.

Influence of structural ordering during cooling on cluster connections

In Fig. 4(a), we show the cluster connection number per atom for the four schemes (1-atom, 2-atom, 3-atom and 4-atom) at room temperature (300 K) for sample #1 to 8 in Table 1. The number of 1-atom and 4-atom cluster connections are the highest and lowest respectively among all the MG samples studied in this work. The relative fractions of the four connection schemes obviously determine the make-up (constitution ratio) of the second peak in RDF, affecting its shape and sometimes causing its splitting (see next section). Meanwhile, in Fig. 4(b) the development of cluster connections (1-atom to 4-atom) among all the samples listed in Table 1 are illustrated. Specifically, each data point plotted is defined as the difference between the glassy state (at 300 K) and the liquid state (at the liquidus temperature). The results in Fig. 4(b) demonstrate firstly that the number of 2-atom, 3-atom and 4-atom connections in an alloy changes as one cools from the equilibrium liquid into a glassy state with increased structural ordering. Specifically, the number of 3-atom connections increases while the number of 2-atom and 4-atom connections is reduced in the glassy state relative to the liquid, similar with other observations16,33,38. In contrast, the average number of 1-atom connections per atom remains almost unchanged when going from the equilibrium liquid to the glassy state. Secondly, the development of 2-atom, 3-atom and 4-atom cluster connections depends on the cooling rate, as illustrated for Cu64Zr36 subjected to different quenching procedures (marked in Fig. 4). Specifically, a sample experiencing a slower cooling rate undergoes more structural ordering, exhibits a more pronounced increase in 3-atom connections and a decrease of the 2-atom and 4-atom connections upon cooling into a glass. Thirdly, examination of the total number of cluster connections in the equilibrium liquids and glassy states in Fig. 4(b) indicates that the increase in 3-atom connections is roughly compensated by a decrease in the number of 2-atom and 4-atom connections such that the total number of connections remains essentially unchanged. What this implies is that the 3-atom cluster connections are the most favored; their number is increased with structural ordering during cooling through the glass transition at the expense of two of the other cluster connections, specifically the 2-atom and 4-atom connections. In other words, two neighboring coordination polyhedra prefer to link together via face sharing rather than edge or squashed-tetrahedra sharing. This can be regarded as a characteristic structural feature of atomic order, for correlations with the second nearest-neighbor shell in amorphous alloys. The increased fraction of 3-atom connections leads to a higher intensity at first sub-peak, which is indeed observed in the RDFs of all the samples we studied.

Splitting of second peak in the radial distribution functions

The split second peak in the RDF and structure factor is often the most eminent observation for some MGs, see Fig. 2(a) and refs. 22,25,31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36. However, this is not a universal phenomenon for all MGs, e.g., Zr46Cu46Al8 samples in Fig. 2(b) lack the splitting in the second peak in the RDF (also see ref. 49). The origin of the split second peak for MGs has been the subject of some debate22,25,33,47,48. Since the splitting is not observed in the data for liquids, most explanations attribute the phenomenon to structural ordering during the transition from the liquid to the glassy state (the SRO develops at increasing rate deep inside the supercooled liquid regime before the glass transition7). Various mechanisms have been proposed to account for the splitting, such as the intensified icosahedral order13, appearance of local translational symmetry22,47, the enhanced unevenness of the connection scheme of the atomic cluster33,35, or “Bergman triacontahedron” packing25 during the glass transition. These explanations all appear to be self-consistent, but there still remains the fundamental question as to whether the splitting of the second peak has to originate intrinsically from the structural ordering near the glass transition. The answer is negative: earlier in Fig. 1(a), we have examined both instantaneous and inherent structure (IS) for an equilibrium Ta liquid at 3300 K and we pointed out that their RDFs are significantly different as the second peak in g(r) is already split for the inherent structure.

In other words, this splitting feature in the RDF appears to be intrinsic even for an equilibrium liquid, where extended icosahedral order or crystalline topological order is absent. This supports the proposition that its origin is cluster connection schemes, because the equilibrium liquid already has a tendency to develop certain type of preferable coordination polyhedra, which connect via the four types of connection schemes. In the instantaneous liquid, with deviations away from the inherent structure and smearing by thermal vibration, the splitting feature is not observed at high temperatures. One thus concludes that the splitting second peak in g(r) for MGs can be inherited from the inherent structure of liquids and not fundamentally determined by the appearance (or not) of new local structure order developed towards glass transition22,25,33,47. As illustrated in Fig. 2 for the four cluster connection schemes, the contributions from 1-atom and 3-atom connections are much stronger in intensity while the 2-atom and 4-atom connections are weaker. Their uneven contributions can cause the splitting of second peak in g(r), as shown in Fig. 2(a) and discussed in ref. 33,35. Usually, the splitting of second peak is more pronounced for monoatomic MGs27, or when the system contains elements of similar atomic sizes27, or at low temperatures. Conversely, when there are multiple constituents, large atomic size difference and strong chemical order or vibrational contributions, the g(r) decomposed for each of the cluster connection schemes would get broadened and their superposition tends to smear out the split second peak in g(r) (see Fig. 1(a) and Fig. 2(b)).

However, the structural ordering during cooling through the glass transition does also have influence on the second peak in g(r), in that the enhancement of 3-atom connections at the expense of both 2-atom and 4-atom connections (see Fig. 4) is expected to cause a shift and intensity changes of the sub-peaks. For instance, Fig. 1(a) compares the g(r) of the inherent structure of Ta liquid and that of Ta MG; in the latter the first sub-peak is more pronounced.

Cluster connection dependence of elastic deformation

Unlike crystalline metals, the elastic deformation of MGs is intrinsically inhomogeneous due to the wide variation in the local structural arrangements28,29,50,51,52,53. Consequently, it is interesting to examine the elastic response with respect to different atomic cluster connections within amorphous solids. Here we use MD simulations to examine the athermal quasi-static shear (AQS)54 deformation of samples #1 to 8 in Table 1 in the nominally elastic regime; we further calculate elastic strains generated between connected coordination polyhedra (calculations are described in the Methods section). In Fig. 5, we plot the average elastic shear strain for each group of cluster connection schemes (colored arrows) in comparison to the imposed macroscopic shear strain; the dashed line in the figure represents where cluster strain equals the imposed macroscopic strain. We observe that i) the elastic strain experienced by clusters connected via the 1-atom classification is almost equivalent to that of the macroscopic deformation; ii) the elastic responses of clusters with both the 2-atom and 4-atom connections behave in a more flexible manner (i.e., they show deformation larger than the macroscopic strain) while clusters with 3-atom connections are the stiffest (i.e., they show the smallest local shear strain). Sharing of triangulated faces between tetrahedra is likely to result in higher energy barrier W of basins in the potential energy landscape, which is known to increase shear modulus G55,56.

The relation between cluster shear strains, γcluster, of different cluster connection schemes in terms of the imposed macroscopic shear strain γimposed for samples #1 to 8 in Table 1.

The dashed line indicates where the cluster strains are equal to the imposed macroscopic shear strains.

Interestingly, the variations in elastic deformation for clusters with the different connections correlate with the observed evolution in the population of these different connection schemes upon cooling. Specifically, as discussed above, the fraction of 3-atom cluster connections (stiffest elastic response among atomic cluster connections) grows during the structural ordering, while the number of 2-atom and 4-atom connections (more flexible elastic response) is reduced. Meanwhile, 1-atom cluster connections, which exhibit an insensitivity to structure ordering, have elastic response equivalent to the macroscopic deformation.

Methods

Sample preparation by MD simulation

Molecular dynamics simulations using the LAMMPS package57 were implemented to study eight metallic glass models, including the metallic glasses Cu64Zr36, Ni80P20, Al90La10, Mg65Cu25Y10 and Zr46Cu46Al8 (Table 1), with the optimized embedded atom method (EAM) potentials, adopted from34,38,39. Each model contained 128,000 atoms with a simulation box length in excess of 10 nm, i.e., large enough to overcome possible issues from periodic boundary conditions for longer length-scale order in metallic glasses and liquids. The liquids for the MD samples were equilibrated for sufficient times at high temperature to assure that the equilibrium state was reached before being quenched to room temperature (300 K) with each specific cooling rate controlled by a Nose-Hoover thermostat (the volume of the sample was controlled through the use of a barostat set to zero pressure)37. Periodic boundary conditions were applied in all three directions. The Voronoi tessellation analysis was employed to investigate the short range order (SRO) according to nearest neighbor atoms from their inherent structures7. The inherent structure was obtained by conjugate-gradient energy minimization with energy threshold of 10−6 eV and force threshold of 10−6 eV/ . The structure analysis of liquids were averaged over 100 configurations for each sample with running time of 1 ns.

. The structure analysis of liquids were averaged over 100 configurations for each sample with running time of 1 ns.

Elastic deformation of metallic glasses

Athermal quasi-static shear (AQS)54 was applied to the metallic glasses under study to avoid any strain rate effects and thermal fluctuations in the MD simulations; a simple shear was applied in the y-z direction in the nominal elastic regime with the strain range of zero to 0.05. To investigate the atomic cluster strain for four different cluster connection schemes, we modified a previous approach for atomic strain proposed by Falk58 and Li59, which was determined by minimizing the mean-square difference between previous and present configuration of atomic clusters. Here the first step was to seek a locally affine transformation matrix Jcluster,α, which can be best used to map:

where  and ΔRji are the separation between central i atom and surrounding j atom at the second nearest-neighbor shell for previous and present configurations, respectively, while α refers to each cluster connection schemes of 1-atom to 4-atom. The Lagrangian strain matrix for α cluster connection schemes can then be calculated as:

and ΔRji are the separation between central i atom and surrounding j atom at the second nearest-neighbor shell for previous and present configurations, respectively, while α refers to each cluster connection schemes of 1-atom to 4-atom. The Lagrangian strain matrix for α cluster connection schemes can then be calculated as:

such that its component in the y-z direction is the atomic cluster strain for a specific cluster connection.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Ding, J. et al. Second-Nearest-Neighbor Correlations from Connection of Atomic Packing Motifs in Metallic Glasses and Liquids. Sci. Rep. 5, 17429; doi: 10.1038/srep17429 (2015).

References

Na, J. H. et al. Compositional landscape for glass formation in metal alloys. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 111, 9031–9036 (2014).

Inoue, A. Stabilization of metallic supercooled liquid and bulk amorphous alloys. Acta Mater. 48, 279–306 (2000).

Greer, A. L. & Ma, E. Bulk metallic glasses: at the cutting edge of metals research. MRS Bull. 32, 611–619 (2007).

Demetriou, M. D. et al. A damage-tolerant glass. Nat. Mater. 10, 123–128 (2011).

Stillinger, F. H. A topographic view of supercooled liquids and glass formation. Science 267, 1935–1939 (1995).

Debenedetti, P. G. & Stillinger, F. H. Supercooled liquids and the glass transition. Nature 410, 259–267 (2001).

Cheng, Y. Q. & Ma, E. Atomic-level structure and structure-property relationship in metallic glasses. Prog. Mater. Sci. 56, 379–473 (2011).

Ma, E. Tuning order in disorder, Nat. Mater. 14, 547–552 (2015).

Sheng, H. W., Luo, W. K., Alamgir, F. M., Bai, J. M. & Ma, E. Atomic packing and short-to-medium-range order in metallic glasses. Nature. 439, 419–425 (2006).

Miracle, D. B. A structural model for metallic glasses. Nat. Mater. 3, 697–702 (2004).

Egami, T. Atomic level stresses. Prog. Mater. Sci. 56, 637–653 (2011).

Nelson, D. R. & Spaepen, F. Polytetrahedral order in condensed matter. Solid State Phys. 42, 1–90 (1989).

Shen, Y. T., Kim, T. H., Gangopadhyay, A. K. & Kelton, K. F. Icosahedral order, frustration and the glass transition: Evidence from time-dependent nucleation and supercooled liquid structure studies. Phys. Rev. Lett. 102, 057801 (2009)..

Hirata, A. et al. Direct observation of local atomic order in a metallic glass. Nat. Mater. 10, 28–33 (2011).

Hirata, A. et al. Geometric Frustration of Icosahedron in Metallic Glasses. Science 341, 376–379 (2013).

Ding, J., Cheng, Y. Q. & Ma, E. Full icosahedra dominate local order in Cu64Zr34 metallic glass and supercooled liquid. Acta Mater. 69, 343–354. (2014).

Ding, J., Cheng, Y. Q., Sheng, H. W. & Ma, E. Short-range structural signature of excess specific heat and fragility of metallic-glass-forming supercooled liquids. Phys. Rev. B. 85, 060201 (2012).

Ding, J., Cheng, Y. Q. & Ma, E. Quantitative measure of local solidity/liquidity in metallic glasses. Acta Mater. 61, 4474–4480 (2013).

Ding, J., Patinet, S., Falk, M. L., Cheng, Y. Q. & Ma, E. Soft spots and their structural signature in a metallic glass. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 111, 14052–14056 (2014).

Ma, D., Stoica, A. D. & Wang, X. L. Power-law scaling and fractal nature of medium-range order in metallic glasses. Nat. Mater. 8, 30–34 (2009).

Zeng, Q. et al. Universal fractional noncubic power law for density of metallic glasses. Phys. Rev. Lett. 112, 185502 (2014).

Liu, X. J. et al. Metallic liquids and glasses: atomic order and global packing. Phys. Rev. Lett. 105, 155501 (2010).

Häussler, P. Analogies and differences between the crystalline and the disordered state. Phys. Status. Solid (c). 1, 2879–2883 (2004).

Häussler, P. Interrelations between atomic and electronic structures—liquid and amorphous metals as model systems. Phys. Rep. 222, 65–143 (1992).

Fang, X. W. et al. Spatially resolved distribution function and the medium-range order in metallic liquid and glass. Sci. Rep. 1, 194 (2011).

Li, M., Wang, C. Z., Hao, S. G., Kramer, M. J. & Ho, K. M. Structural heterogeneity and medium-range order in ZrxCu100−x metallic glasses. Phys. Rev. B. 80, 184201 (2009).

Wu, Z. W., Li, M. Z., Wang, W. H. & Liu, K. X. Hidden topological order and its correlation with glass-forming ability in metallic glasses. Nat. Comm. 6, 6035 (2015).

Wakeda, M. & Shibutani. Y. Icosahedral clustering with medium-range order and local elastic properties of amorphous metals. Acta Mater. 58, 3963–3969 (2010).

Wu, Z. W., Li, M. Z., Wang, W. H. & Liu, K. X. Correlation between structural relaxation and connectivity of icosahedral clusters in CuZr metallic glass-forming liquids. Phys. Rev. B. 88, 054202 (2013).

Zhang, Y. et al. Cooling rates dependence of medium-range order development in Cu64.5Zr35.5 metallic glass. Phys. Rev. B. 91, 064105 (2015).

Bennett, C. H. Serially deposited amorphous aggregates of hard spheres. J. Appl. Phys. 43, 2727–2734 (1972).

Lee, M., Lee, C. M., Lee, K. R., Ma, E. & Lee, J. C. Networked interpenetrating connections of icosahedra: Effects on shear transformations in metallic glass. Acta Mater. 59, 159–170 (2011).

Pan, S. P., Qin, J. Y., Wang, W. M. & Gu, T. K. Origin of splitting of the second peak in the pair-distribution function for metallic glasses. Phys. Rev. B. 84, 092201 (2011).

Cheng, Y. Q., Ma, E. & Sheng, H. W. Atomic level structure in multicomponent bulk metallic glass. Phys. Rev. Lett. 102, 245501 (2009).

Luo, W. K., Sheng, H. W. & Ma, E. Pair correlation functions and structural building schemes in amorphous alloys. Appl. Phys. Lett. 89, 131927 (2006).

van de Waal, B. W. On the origin of second-peak splitting in the static structure factor of metallic glasses. J. Non-Cryst. Solids. 189, 118–128 (1995).

Allen, M. P. & Tildesley, D. J. Computer Simulation of Liquids (Clarendon Press, 1987).

Ding, J., Cheng, Y. Q. & Ma, E. Charge-transfer-enhanced prism-type local order in amorphous Mg65Cu25Y10: Short-to-medium-range structural evolution underlying liquid fragility and heat capacity. Acta Mater. 61, 3130–3140 (2013).

Ding, J. & Cheng, Y. Q. Charge transfer and atomic-level pressure in metallic glasses. Appl. Phys. Lett. 104, 051903 (2014).

Zhong, L., Wang, J., Sheng, H., Zhang, Z. & Mao, S. X. Formation of monatomic metallic glasses through ultrafast liquid quenching. Nature 512, 177–180 (2014).

Stillinger, F. H. & Weber, T. A. Packing structures and transitions in liquids and solids. Science 225, 983–9 (1984).

Jonsson, H. & Andersen, H. C. Icosahedral ordering in the Lennard-Jones liquid and glass. Phys. Rev. Lett. 60, 2295–2298 (1988).

Jakse, N. & Pasturel, A. Local order of liquid and supercooled zirconium by ab initio molecular dynamics. Phys. Rev. Lett. 91, 195501 (2003).

Stillinger, F. H. & Weber, T. A. Computer simulation of local order in condensed phases of silicon. Phys. Rev. B. 31, 5262 (1985).

Ding, J. et al. Temperature effects on atomic pair distribution functions of melts. J. Chem. Phys. 140, 064501 (2014).

Smithells, C. J. Smithells Metals Reference Book 7th edn (eds E. A. Brandes & G. B. Brook ) (Butterworth-Heinemann, 1992).

Liu, X. J. et al. (2011). Atomic packing symmetry in the metallic liquid and glass states. Acta Mater. 59, 6480–6488 (2011).

Gardner, P. P., Cowlam, N. & Davies, H. A. Measurements of metallic glass structures under conditions of high spatial resolution. J. Phys. F. Metal. Phys. 15, 769 (1985).

Fang, H. Z., Hui, X., Chen, G. L. & Liu, Z. K. Al-centered icosahedral ordering in Cu46Zr46Al8 bulk metallic glass. Appl. Phys. Lett. 94, 1904 (2009).

Dmowski, W., Iwashita, T., Chuang, C.-P., Almer, J. & Egami, T. Elastic heterogeneity in metallic glasses. Phys. Rev. Lett. 105, 205502 (2010).

Poulsen, H. F., Wert, J. A., Neuefeind, J., Honkimäki, V. & Daymond, M. Measuring strain distributions in amorphous materials. Nat. Mater. 4, 33–36 (2005).

Hufnagel, T. C., Ott, R. T. & Almer, J. Structural aspects of elastic deformation of a metallic glass. Phys. Rev. B. 73, 064204 (2006).

Ding, J., Cheng, Y. Q. & Ma, E. Correlating local structure with inhomogeneous elastic deformation in a metallic glass. Appl. Phys. Lett. 101, 121917 (2012).

Maloney, C. E. & Lemaitre, A. Amorphous systems in athermal, quasistatic shear. Phys. Rev. E. 74, 016118 (2006).

Johnson, W. L. & Samwer, K. A universal criterion for plastic yielding of metallic glasses with a (T/T g) 2/3 temperature dependence. Phys. Rev. Lett. 95, 195501 (2005).

Johnson, W. L., Demetriou, M. D., Harmon, J. S., Lind, M. L. & Samwer, K. Rheology and ultrasonic properties of metallic glass-forming liquids: A potential energy landscape perspective. MRS Bull. 32, 644–650 (2007).

Plimpton, S. Fast parallel algorithms for short-range molecular dynamics. J. Comput. Phys. 117, 1–19 (1995).

Falk, M. L. & Langer, J. S. Dynamics of viscoplastic deformation in amorphous solids. Phys. Rev. E. 57, 7192 (1998).

Li, J. AtomEye: an efficient atomistic configuration viewer. Model. Simul. Mater. Sci. Eng. 11, 173 (2003).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Mechanical Behavior of Materials Program at the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, funded by the U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Science, Office of Basic Energy Sciences, Materials Sciences and Engineering Division, under Contract No. DE-AC02-05CH11231. E.M. has been supported at JHU by National Science Foundation, DMR-1505621. This work made use of resources of the National Energy Research Scientific Computing Center, supported by the Office of Basic Energy Sciences of the U.S. Department of Energy under Contract No. DE-AC02-05CH11231. We thank Y.Q. Cheng for thoughtful discussion.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.D. conceived and designed the research and analysis and performed the molecular dynamics simulations. J.D., E.M. M.A. and R.R. wrote the paper. All authors discussed the results and revised the manuscript.

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Ding, J., Ma, E., Asta, M. et al. Second-Nearest-Neighbor Correlations from Connection of Atomic Packing Motifs in Metallic Glasses and Liquids. Sci Rep 5, 17429 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep17429

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/srep17429

This article is cited by

-

Unveiling the local structure of the amorphous metal \(\text {Fe}_{(1-x)}\text {Zr}_x\) combining first-principles-based simulations and modelling of EXAFS spectra

Scientific Reports (2023)

-

Plasticity in diamond nanoparticles: dislocations and amorphization during loading and dislocation multiplication during unloading

Journal of Materials Science (2023)

-

Developing novel amorphous alloys from the perspectives of entropy and shear bands

Science China Materials (2023)

-

Phase transformation behavior of a dual-phase nanostructured Fe-Ni-B-Si-P-Nb metallic glass and its correlation with stress-impedance properties

Rare Metals (2023)

-

Effect of composition and thermal history on deformation behavior and cluster connections in model bulk metallic glasses

Scientific Reports (2022)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.