Abstract

Plutonium isotopes have primarily been injected to the stratosphere by the atmospheric nuclear weapon tests and the burn-up of the SNAP-9A satellite. Here we show by using published data that the stratospheric plutonium exponentially decreased with apparent residence time of 1.5 ± 0.5 years and that the temporal variations of plutonium in surface air followed the stratospheric trends until the early 1980s. In the 2000s, plutonium and its isotope ratios in the atmosphere varied dynamically and sporadic high concentrations of 239,240Pu reported for the lower stratospheric and upper tropospheric aerosols may be due to environmental events such as the global dust outbreaks and biomass burning.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Atmospheric behavior of anthropogenic radionuclides, which originated from atmospheric nuclear weapons tests, satellite accidents and nuclear reactor accidents has been frequently studied both in terrestrial and marine environment during the past 50 years1,2. Large quantities of radionuclides were released into the atmosphere during atmospheric tests of nuclear weapons conducted by USA and former Soviet Union, mainly during the 1950s and early 1960s. During the large-scale nuclear weapons tests of hydrogen bombs, most of the radioactive debris reached the stratosphere, which became then the main reservoir of bomb-produced radionuclides. Exchange processes between the stratosphere and the troposphere, especially during the late spring when rising hot air provokes the descent of cold air masses from the lower stratosphere, enhanced concentrations of radionuclides in the troposphere (global fallout), producing regularly observed spring maxima in radionuclide concentrations in the mid-latitude regions.

After the moratorium on the atmospheric nuclear weapons tests signed in 1963, the new supply of bomb-produced radionuclides to the stratosphere was limited because of only minor contributions from atmospheric nuclear weapons tests conducted by France and China up to 1980. Therefore maxima in concentrations of bomb-produced radionuclides (e.g. 14C with a half life of 5,730 years; 90Sr with a half-life of 28 years; 137Cs with a half life of 30 years; 238Pu with a half life of 87.74 years; 239Pu with a half life of 24,100 years; 240Pu with a half life of 6,560 years and 241Pu with a half life of 14.4 years) in the lower troposphere were observed in 1963 (ref. 1, 2, 3). The typical spring maxima in the ground-level air caused by the stratosphere-troposphere inputs were observed till the 1990s. Later, the observed radionuclide variations have been mostly due to their resuspension from soil2,4,5,6,7,8. It has been believed therefore that there have not been significant amounts of these radionuclides left in the stratosphere because most of the radionuclides derived from the atmospheric nuclear testing conducted from 1945 to 1980 had already been transported to the lower troposphere and deposited on land and ocean surface2,9.

Stratospheric residence time of radioactive aerosols is an important concept characterizing stratospheric behavior of particles. In the 1960s, longer mean residence times of the order of 1–4 years were specified to bomb-derived radioactive aerosols in the stratosphere10,11,12. After 1970, a shorter stratospheric residence time (1–2 y) was determined from temporal changes of stratospheric distributions of bomb-derived radionuclides13, as well as from long-term continuous monitoring of their concentrations in ground-level air3,14. Models related to stratospheric transport were developed and the stratospheric residence time of gaseous chemical components such as CO2 and SF6, were calculated. The obtained residence time of gaseous chemicals in the mid-latitude stratosphere was in the range of 1.1 to 2.1 y (ref. 15).

Recently Corcho Alvarado et al.16 reported interesting results of investigations of plutonium isotopes and 137Cs in stratospheric and tropospheric aerosols, which included new data observed during the period of 2007 to 2011. They found higher 239,240Pu and 137Cs concentrations and higher 238Pu/239,240Pu activity ratios in the lower stratosphere and lower troposphere than expected. The observed levels of 239,240Pu in stratospheric aerosols were from two to four orders of magnitude higher than that in the ground-level air. They also suggested that the stratospheric mean residence time of plutonium and 137Cs should be 2.5–5 y, arguing that radionuclides attached to fine aerosol particles (<0.02 μm in diameter) could have a longer stay in the stratosphere and therefore radionuclides injected there mainly during the early 1960s have still been present during the 2000s in the stratosphere. However, studying long-term variations (1964–2010) of plutonium isotopes in the stratosphere and surface air of the Northern Hemisphere we have found that the dominant processes affecting plutonium concentrations in the upper troposphere should be global dust events and biomass burning and that its apparent residence time in the atmosphere did not change from 1.5 ± 0.5 years.

Results

Sources of plutonium in the atmosphere

The 238Pu, 239Pu, 240Pu and 241Pu represent the major plutonium isotopes released to the atmosphere during the atmospheric nuclear test1. Their isotope ratios (238Pu/239,240Pu, 240Pu/239Pu, 241Pu/239,240Pu) are powerful tools to elucidate sources of plutonium in the environment. For nuclear bomb-derived plutonium (global fallout), the 238Pu/239,240Pu activity ratio has been 0.03, the 241Pu/239,240Pu activity ratio in 1963 was 13–15 (ref. 17,18) and the 240Pu/239Pu atom ratio has been 0.18 (ref. 19, 20, 21). The plutonium isotope ratios derived from the nuclear weapons tests depend on explosion yields and the plutonium isotope composition of fissile materials. High 241Pu/239,240Pu activity ratios (27–30; ref. 20,22), high 240Pu/239Pu atom ratios (0.3; ref. 20,23, 24, 25, 26) and lower 238Pu/239,240Pu activity ratios (<0.01; ref. 20) were observed after high-yield thermonuclear tests carried out by US in the 1950s, whereas lower 240Pu/239Pu atom ratios (0.036–0.063) appeared in low yield tests carried out by US (Nevada test site)27,28 and former USSR (Semipalatinsk test site)29.

Nuclear power plant accidents such as Chernobyl and Fukushima were also sources of plutonium in the environment, although they were much lower scale events. Plutonium isotopes released from these accidents were characterized by higher 238Pu/239,240Pu, 241Pu/239,240Pu activity ratios and higher 240Pu/239Pu atom ratios than those ratios derived from nuclear tests6. The 238Pu/239,240Pu, 241Pu/239,240Pu activity ratios and 240Pu/239Pu atom ratio for the Chernobyl accident were 0.5, 85 and 0.41, respectively17,30,31, while for the Fukushima accident these ratios were 1.2, 108 and 0.30–33, respectively32,33. The plutonium isotopic signature may help therefore to better understand sources of anthropogenic radionuclides and their behavior in the upper and lower atmosphere.

For better understanding of plutonium levels in the stratosphere it is therefore important to elucidate sources of the bomb-derived plutonium and other radionuclides observed in stratospheric aerosols in the 2000s. Possible radionuclide sources are the large-scale nuclear tests carried out in 1961–62, the Chinese nuclear tests (especially those conducted in 1976 and 1980), resuspension of plutonium from deserts and biomass burning. To achieve this aim, we collected data of plutonium isotope concentrations in stratospheric air and in surface air in the Northern Hemisphere. Unfortunately, a continuous data set of both stratospheric and ground-level plutonium levels during the period of 1960–2010 has not been possible to construct. We describe here long-term variations (1964–2010) of plutonium isotopes in the stratosphere and surface air of the Northern Hemisphere using available data.

Temporal variations of 239,240Pu in the stratosphere and surface air

Large data sets on plutonium isotopes in stratospheric and ground-level aerosols is available from the Environmental Measurements Laboratory (EML, USA)34, which conducted high-altitude aerosol monitoring programs from the early 1960s to the early 1980s (ref. 35). We used 238Pu and 239,240Pu activity concentrations in the Northern Hemisphere stratospheric air (20–40 km altitude), in which unreliable results with high measuring uncertainties were removed (Fig. 1). The data obtained by Corcho Alvarado et al.16 from 1973 to 2009 for the lower stratosphere (10.1–14.2 km altitude) were included in Fig. 1 as well. Further, plutonium isotopes results obtained for surface air at mid-latitude region of the Northern Hemisphere were also included in Fig. 1: New York (USA, 40° 45′N, 74° 00′W), Beaverton Oregon (USA, 45° 32′N, 122° 53′W)34, Tsukuba (Japan, 36° 03′N, 140° 08′E)36,37, Prague (Czech Republic, 50° 04′N, 14° 26′E)7, Braunschweig (Germany, 52° 17′N, 10° 33′E)38, Vilnius (Lithuania, 54° 42′N, 25° 30′E)6 and Milford Haven (UK, 51° 43′N, 5° 02′W)39. All plutonium isotope concentrations in surface air were determined at monthly or quarterly basis.

Temporal variations of 239,240Pu concentrations in stratospheric and surface air of the Northern Hemisphere.

Closed red circles: the upper stratosphere (20–40 km height; data from ref. 34); open blue circles: the lower stratosphere (10.1–14.2 km height; data from ref. 16); closed black squares: the surface air (New York; data from ref. 34); brown closed rhombic: the surface air (Beaverton Oregon; data from ref. 34); green closed rhombic: the surface air (Milford Haven; data from ref. 39); purple squares: the surface air (Tsukuba; data from ref. 36,37); brown closed squares: the surface air (Braunschweig; data from ref. 38); green closed circles: the surface air (Prague; data from ref. 7); blue closed rhombic: the surface air (Vilnius; data from ref. 6).

The stratospheric 239,240Pu levels showed a maximum in 1963 (Fig. 1) associated with large-scale atmospheric nuclear weapons tests conducted mainly during 1961-62. There were several peaks of the stratospheric 239,240Pu in the 1970 s, which correspond to Chinese thermonuclear explosions (total yield of 6.5 Mt in 14 October 1970, 2.5 Mt in 27 June 1973 and 4 Mt in 17 November 1976)9. After the 1976 Chinese thermonuclear explosion, the stratospheric 239,240Pu concentrations decreased with an apparent stratospheric residence time of 1.3 ± 0.3 y. The apparent residence time of the stratospheric 239,240Pu of 2.5–5 y suggested in ref. 16, which is based on the data from 1965 to 2010, is difficult to accept because there are no data available for more than one decade (1987–2003).

A pronounced peak of 239,240Pu concentration in surface air of New York occurred at delay of about 17 months after the 1976 Chinese thermonuclear test (Fig. 1). The surface 239,240Pu concentration decreased then with the apparent residence time of 1.3 ± 0.3 y (similar to that observed for stratospheric aerosols) until the end of 1980. The surface 239,240Pu concentrations showed seasonal variations - a late spring maximum and a winter minimum, in contrast of the stratospheric 239,240Pu levels40. After the 1980 Chinese nuclear test (total yield of 0.6 Mt in 16 October 1980), a small peak of 239,240Pu occurred in the upper stratosphere, which is consistent with the result that most of plutonium from the 1980 Chinese nuclear test was injected into the lower stratosphere and the AME layer just above tropopause14. Irrespective of location of surface monitoring sites (New York, Beaverton, Tsukuba, Milford Haven), the surface 239,240Pu levels showed marked increase in spring 1981. After 1982, a decrease with the apparent stratospheric residence time of about 1.3 ± 0.3 y was observed until 1984, which means that the surface plutonium until the early 1980s was controlled by the stratospheric inputs. These findings confirm therefore that significant amounts of 239,240Pu and fission products in the upper stratospheric air in the 1970s and in the early 1980s were derived from the series of the Chinese nuclear weapons tests.

The 239,240Pu levels observed in the lower stratosphere during 2007–2008 were by about two orders of magnitude larger than those observed in surface air6,16,31. The 239,240Pu concentrations are expressed per standard cubic meter (15 °C, 101.325 kPa), however, the pressure at 10 km of altitude is about one order of magnitude lower than that in ground-level air. The thermodynamics indicates that sampling volumes in high altitudes are greater than the SCM, therefore it is difficult exactly compare radionuclide concentrations measured at high altitudes with those measured at ground-level air. Another point is a difference of sampling periods between surface and high altitudes measurements. High altitude sampling was usually carried out only for hours, whereas sampling periods of surface air were one to three months. Therefore short-term sporadic events occurring at high altitudes need not be visible in monthly or three months mean values observed at ground-level air.

There are no data available on plutonium concentrations in stratospheric aerosols during the period from June 1986 to October 2004 (Fig. 1). On the other hand, the plutonium isotope levels in surface air were measured in several monitoring sites, most of which were located in Europe. The plutonium concentrations in surface air were as follows: <2.5 to 9.5 nBq m−3 during the period from 1986 to 1989 (as quarterly means) at Milford Haven39; 0.53 to 8.1 nBq m−3 during the period from 1987 to 1998 (as annual means) at Neuherberg41; 0.39 to 4.5 nBq m−3 during the period from 1990 to 2003 (as quarterly means) at Braunschweig38; 0.53 to 217 nBq m−3 during the period from 1997 to 2006 (as quarterly means) at Prague7; 2.2 to 49 nBq m−3 during the period from 2005 to 2006 (as monthly means) at Vilnius (54° 42′N, 25° 30′E)6; and 1.7 to 15 nBq m−3 during the period from 2001 to 2002 (as monthly means) at Seville (37° 22′N, 5° 59′W)42. The results suggest that most of the 239,240Pu concentrations in surface air during the period from 1986 to 2006 were in the range of 1 to 10 nBq m−3 in the mid-latitude region of the Northern Hemisphere, except of specific events such as a local contamination7, Chernobyl accident6 and dust events4,5. The 239,240Pu concentrations in surface air did not show decreasing rates and similar trends were observed for the 239,240Pu deposition4,41. These findings revealed that the 239,240Pu concentrations in surface air since 1986 were not under a stratospheric control.

New 239,240Pu data for a lower stratosphere are available from October 2004, when they decreased from 0.5 μBq m−3 to 0.12 μBq m−3 measured in November 2006, in agreement with data obtained during 1986 (ref. 16). Later on, elevated 239,240Pu levels were observed in May 2007 (3.9 μBq m−3), July 2007 (5.6 μBq m−3) and October 2008 (9.7 μBq m−3). The last value re-measured in the same day16 was, however, only 0.35 μBq m−3, indicating a large heterogeneity in the distribution of 239,240Pu in the lower stratosphere. Figure 1 clearly shows that the data obtained during 2007–2008 are outside of the 239,240Pu stratospheric trend. A new source of plutonium in the stratosphere should be therefore considered.

Temporal variations of stratospheric 238Pu

It has been suggested16 that higher 238Pu/239,240Pu activity ratios observed in stratospheric aerosols in the 2000s may be due to 238Pu from burn-up of the US satellite SNAP-9A, which occurred in 1964 at about 50 km altitude over the Southern Hemisphere. The stratospheric behavior of 238Pu differed thus from that of 239,240Pu because most of the 238Pu in the stratosphere after 1964 originated from the burn-up of the SNAP-9A satellite, as the stratospheric inventory of the bomb-derived 238Pu was estimated to be only about 2% of its total inventory in 19661,43. On the other hand, the stratospheric 239,240Pu in the mid 1960s originated mainly from the 1961–62 nuclear weapons testing. In order to trace SNAP-9A satellite-derived 238Pu in the stratosphere, it is therefore more appropriate to examine temporal variations of 238Pu concentrations in the stratospheric aerosols rather than 238Pu/239,240Pu activity ratios. The stratospheric 238Pu was a good indicator of fine particles injected into the upper stratosphere because 238Pu-bearing particles had a physical size distribution with a median at about 0.01 μm of oxide spheres (PuO2)44.

The observed temporal variations of the 238Pu concentrations in stratospheric air in the period from 1965 to 1986 showed an exponential decrease (Fig. 2), with an apparent stratospheric residence time of 1.7±0.4 y, consistent with previous results43. The result reveals that stratospheric 238Pu concentrations showed altitude-depended distribution: higher 238Pu concentrations occurred in the upper stratosphere (20–40 km altitude), whereas lower 238Pu levels were observed in the lower stratosphere (10.1–14.2 km altitude), which suggests that temporal variations of atmospheric 238Pu were controlled by the upper stratospheric 238Pu derived from the SNAP-9A burn-up and partly due to the Chinese nuclear explosions. The 238Pu concentrations measured in the stratospheric air in the 2000s were, however, of the same order of magnitude as that during the 1970s and 1980s. It has been suggested16 that the high 238Pu levels observed during the 2000s were still due to the SNAP-9A burn-up. It is difficult to consider, however, that the supply of the SNAP-9A-derived 238Pu from the upper stratosphere in the 2000s was the same level as that during the 1970s, i.e. two orders of magnitude higher than levels observed in 1986 and when between 1986 and 2007 typical global fallout 238Pu levels were observed in the lower stratosphere16. In fact, most of the SNAP-9A-derived 238Pu was deposited on the land surface until the end of 1970s (ref. 14). The decreasing trend in the 238Pu levels in the stratosphere up to the mid of the 1980s is also clearly visible in Fig. 2. The elevated 238Pu levels observed in the lower stratosphere in the mid of 2000s (ref. 16) should come therefore from other sources than the burn-up of the SNAP-9A satellite.

Plutonium isotope ratios signatures

The 1961–62 large-scale nuclear tests of the former USSR included a 50 megaton nuclear bomb at Novaya Zemlya9, in which a significant amount of nuclear debris was injected into the upper stratosphere. The total explosion yields of the Chinese 1976 and 1980 atmospheric nuclear tests were only 4 and 0.6 megatons9, respectively, in which the nuclear debris was injected into the lower stratosphere14 only. If the high yield tests in 1961–62 caused higher 239,240Pu concentrations in stratospheric aerosols observed in the 2000s, it is expected that stratospheric aerosol plutonium collected in the 2000s would show lower 238Pu/239,240Pu activity ratios (<0.01) and higher 240Pu/239Pu atom ratios (>0.3). The 240Pu/239Pu atom ratios in aerosols observed in the 2010s at 3 km height were, however, near that of soil samples (0.18; ref. 19,26), suggesting thus that a source of plutonium should be a resuspension of global fallout deposited plutonium from the earth surface. Higher 238Pu/239,240Pu activity ratios and higher 240Pu/239Pu atom ratios observed in European surface air suggest that source of plutonium should be a resuspension of the Chernobyl-derived plutonium6.

The 241Pu/239,240Pu activity ratio is also a good indicator of plutonium sources in the environment because 241Pu has a relatively short half-life (14.4 years). The 241Pu/239,240Pu activity ratios observed in stratospheric aerosols in the 1970s (12–14) coincided with that observed in deposition samples in 1977 (11; ref. 45). If a major contribution of the stratospheric plutonium was only global fallout, expected 241Pu/239,240Pu ratios in 1977 and 2005 would be 6 and 2, respectively, assuming that the initial 241Pu/239,240Pu activity ratios in global fallout was 12.8 (ref. 18). Most of the stratospheric plutonium observed in the 1970s was derived from the Chinese atmospheric nuclear tests, which were conducted in the 1970s. The lower 241Pu/239,240Pu ratios (ranging from 1.5 to 3.2) observed during the 2000s (ref. 16) in the troposphere (3–13 km altitude), represent therefore aged plutonium derived from global fallout.

The 239,240Pu/137Cs activity ratios observed in stratospheric aerosols during the 2000s showed a larger variability16 than the ratios observed in deposition samples during 2000–2006 (from 0.64 to 8.9 % with a median of 2.5 %; ref. 46). This finding suggests that there are more than two sources of radionuclides in the upper atmosphere, because it is likely that radionuclide composition in the stratospheric aerosols is homogenized throughout a long-time mixing.

Discussion

Redistribution of plutonium in the atmosphere

Corcho Alvarado et al.16 revealed that significant amounts of plutonium isotopes and 137Cs existed in the lower stratosphere during the 2000s, which could be transported to the lower troposphere. The recent observations of 239,240Pu, 14C and 137Cs concentrations in surface air8,38 did not show, however, typical spring maxima, which were observed until the late 1980s when stratosphere-troposphere radionuclide transport was dominant (see also Fig. 1 for 239,240Pu). These maxima occurred due to the transport of lower stratospheric air masses containing high radionuclide levels to the upper troposphere. Similar variations have been observed for cosmogenic 7Be produced by interactions of cosmic ray particles with nitrogen and oxygen atoms mainly in the lower stratosphere and the upper troposphere. Higher 137Cs concentrations in winter months and lower concentrations in summer months are apparent for the last decade, which are more similar to variations of terrigenic 210Pb (a decay product of 222Rn) than for the 7Be variations of the stratospheric origin8,47,48,49,50. Clearly, there is no more stratospheric influence on the 137Cs concentration in surface air, otherwise the 137Cs maxima would be observed in the late spring, similarly as the 7Be spring maxima, which are still observed in the ground-level air. This change in the 137Cs record in the atmosphere is connected with the fact that resuspended 137Cs has become important source of tropospheric radioactivity. Similarly 14C variations observed in the troposphere after 1990s have been due to 14C decreases during winter caused by the Suess effect8,51. Therefore the absence of spring maxima in 239,240Pu, 137Cs and 14C records during the 2000s suggests that the stratospheric transport does not play anymore a dominant role, but a resuspension from soil or other processes may be responsible for observed radionuclide variations in the atmosphere.

Global desert dust events

Desert dust events, well known as Saharan dust and Asian dust (Kosa), have been loading large amounts of soil particles into the atmosphere. Saharan dust transport has been known as the biggest global event redistributing aerosols in the atmosphere52. The Asian dust clouds and similarly the Saharan dust clouds were transported in the mid-latitude region around the globe53. Since soil particles contain anthropogenic radionuclides primarily derived from global fallout and the Chernobyl accident, Saharan and Asian dusts could cause sporadically increasing anthropogenic radionuclide levels in the atmosphere. Asian dusts were characterized by temporal variations of 239,240Pu and 137Cs deposition4,46,54,55. Similarly, the Saharan dusts cause enhancements of 137Cs and 239,240Pu concentrations in the atmosphere and in the deposition, which were observed in Monaco47,50,56,57,58 and south of France49. The Saharan dust is characterized by specific isotope ratios (238Pu/239,240Pu: 0.028, 241Pu/239,240Pu: 3.1, 240Pu/239Pu (atom ratio): 0.192, 241Am/239,240Pu: 0.44, 239,240Pu/137Cs: 0.027; ref. 49).

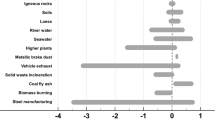

It has been shown that during Saharan dust events aerosols can reach 10 km altitude59 and thus they can influence radionuclide concentrations in the upper troposphere. Many Saharan dust events were observed by Lidars during the 2000s at altitudes around 10 km (ref. 60, 61, 62). A special year was 2008 when the number of Saharan events exceeded 1000 events/month, with maximum of 2500 events observed in March63. The Asian dust clouds generated during the storm in China′s Taklimakan Desert (April 2008) were also lofted to the upper troposphere, to around 8–10 km altitude60. Global dust maps ( http://earthobservatory.nasa.gov/GlobalMaps/?eocn=topnav&eoci=globalmaps), which cover events originating not only over Sahara and Asia, but also over North America, Middle East, etc. showed large-scale dust events during 2007 and 2008. The dust outbreaks may thus cause sporadic high 239,240Pu levels in the upper troposphere due to high load of surface soil dusts (~mg m−3; ref. 49,58) and 239,240Pu concentrations in soil (several Bq kg−1; ref. 5) and they are therefore possible candidates of observed enhanced plutonium and 137Cs levels in the upper and lower troposphere.

Biomass burning

Other strong candidates of anthropogenic radionuclide variations in the troposphere are forest and grassland fires when huge amounts of particles of submicrometer size are released to the air64. The radionuclides derived from the Chernobyl accident as did global fallout had been contaminated in wide areas of Eurasia9, which could be lifted back to the atmosphere. The wildfire events could be enhanced by specific meteorological conditions, such as temperature inversions and/or rain events at remote places, causing secondary deposition of 137Cs (ref. 65,66). Smoke plumes from biomass fires, could reach several kilometers height and they can travel distances as long as several thousand of kilometers. They could even penetrate the tropopause and reach the lower stratosphere67,68. The biomass burning events could be under specific conditions combined with Saharan dust events causing thus global aerosol impact on the atmosphere. Under specific meteorological conditions they could stay in the atmosphere for several weeks. As around 50 Mha of forest and roughly ten times more grassland are burnt annually, the biomass burning represents important way of radionuclide transport in the environment69. The biomass burning plumes originating in Eurasia may redistribute global fallout and Chernobyl deposited sources of anthropogenic radionuclides (e.g. 137Cs and 239,240Pu) in the atmosphere, which could change concentrations, as well as isotope ratios of these radionuclides in the atmosphere6,31. An intense biomass burning observed during 2010 in western Russia released around 1 TBq of 137Cs to the atmosphere, which enhanced airborne 137Cs concentrations up to ~30 μBq m−3 at Moscow region, which coincided with aerosol optical measurements70.

Large-scale volcanic eruptions

It has been suggested16 that by about three orders of magnitude higher 239,240Pu (from 8 to 24 μBq m−3) and 137Cs (around 1 mBq m−3) levels observed in 20 April 2010 in lower troposphere aerosols (altitude 1–3 km) were due to eruption of the Eyjafjallajökull volcano. Sampling carried out the following date showed, however, only global fallout values, as did the sampling carried one year later (30 March 2011) at the altitude of 5.2 and 7.9 km. Elevated radionuclide levels were also reported in 2007 and 2008 in lower stratosphere aerosols (altitude 10.7–12.5 km). On the other hand, no increase in the 239,240Pu and 137Cs concentrations was observed during 2007–2010 in ground-level aerosols16.

A much bigger volcano eruption than the Eyjafjallajökull one was the Mt. Pinatubo (15°08′N, 120°21′E) eruption, which occurred on June 12–16, 1991 and was one of the 20th century′s greatest volcanic eruptions71. As a result of this powerful eruption, 15–20 megatons of SO2 were injected into the stratosphere, as the eruption columns reached 40 km in altitude. Sulfuric acid and/or sulfate aerosols transformed from SO2 can effectively attach radionuclide-bearing particles and remove them from the stratosphere by a residence time of about 13 months for the Pinatubo aerosol cloud72. Unfortunately, there are no stratospheric/tropospheric data available during the 1990s to confirm/discard the volcano hypothesis. As shown in Fig. 1, no enhanced 239,240Pu concentration after the Pinatubo eruption, as did 239,240Pu deposition4,46 was observed in surface air. It is likely therefore that remnants of radionuclides derived from the nuclear tests from 1950 to 1980 and from the satellite burn-up in 1964 were already removed from the stratosphere before injection of the Pinatubo aerosol cloud. This has been supported by observations of 7Be and 137Cs concentrations in summer of 1991 (ref. 47). Therefore there is no obvious evidence of enhanced removal of stratospheric anthropogenic radionuclides due to stratospheric injection of sulfate and ash by large-scale volcanic eruptions.

Sea-spray effects

It has been pointed out that sea spray may be another potential source of plutonium in the atmosphere73,74. However, the contribution of plutonium from sea salt to atmospheric plutonium deposition is much lower than that from soil (<0.3%)4. It was estimated that a contribution of plutonium from major constituent in sea salt (chloride) in surface air of Tsukuba was below 1 μBq m−3. The plutonium/chloride ratio in seawater was 0.5 μBq of Pu per gram of Cl (assuming that plutonium in seawater is homogeneously attached on sea-salt particles)75. The calculated maximum contribution of sea-spray plutonium in the atmosphere is less than 0.006 nBq m−3, which is by 2–3 orders of magnitude lower than from other potential plutonium sources.

We may conclude that our studies of long-term variations (1964–2010) of plutonium isotopes in the stratosphere and troposphere of the Northern Hemisphere suggest that plutonium levels in ground-level air followed the stratospheric trends until the early 1980s. In the 2000s, plutonium and its isotope ratios in the atmosphere varied dynamically and sporadic high concentrations of 239,240Pu reported for the lower stratospheric and upper tropospheric aerosols may be due to environmental events such as the global dust outbreaks and biomass burning. Long-term measurements of plutonium isotopes in the stratosphere and troposphere revealed that the plutonium concentrations in the stratosphere and the troposphere decreased with apparent residence time of 1.5 ± 0.5 y. The plutonium concentrations in surface air, irrespective of sampling sites in the mid-latitude regions, decreased following the changes in the stratospheric plutonium concentrations.

Anthropogenic radionuclides in the troposphere and the lower stratosphere have been useful tools for better understanding of dynamical processes of aerosols in the atmosphere. Knowledge of their temporal variations has also been important pre-requisites for climate change studies and assessment of radioecological impacts of nuclear facilities accidents on the atmospheric and terrestrial environments76.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Hirose, K. and Povinec, P. P. Sources of plutonium in the atmosphere and stratosphere-troposphere mixing. Sci. Rep. 5, 15707; doi: 10.1038/srep15707 (2015).

References

Harley, J. H. Plutonium in the environment - a review. J. Radiat. Res. 21, 83–104 (1980).

Livingston, H. D. & Povinec, P. P. Millennium perspective on the contribution of global fallout radionuclides to ocean science. Health Phys. 82, 656–668 (2002).

Katsuragi, Y. A study of 90Sr fallout in Japan. Pap. Meteor. Geophys. 37, 15–36 (1983).

Hirose, K. et al. Recent trends of plutonium fallout observed in Japan: plutonium as a proxy for desertification. J Environ. Monit. 5, 1–7 (2003).

Hirose, K. et al. Depositional behaviors of plutonium and thorium at Tsukuba and Mt. Haruna in Japan indicate the sources of atmospheric dust. J. Environ. Radioact. 101, 106–112 (2010).

Lujaniené, G. et al. Plutonium isotopes and 241Am in the atmosphere of Lithuania: A comparison of different source terms. Atmos. Environ. 61, 419–427 (2012).

Hölgye, Z. Plutonium isotopes in surface air of Prague in 1986 – 2006. J. Environ. Radioact. 99, 1653–1655 (2008).

Povinec, P. P. et al. Long-term variations of 14C and 137Cs in the Bratislava air - implications of different atmospheric transport processes. J. Environ. Radioact. 108, 33–40 (2012).

United Nations Scientific Committee on the Effects of Atomic Radiation, UNSCEAR, Sources and Effects of Ionising Radiation (UNSCEAR, Vienna, 2000).

Feely, H. W. et al. Transport and fallout of stratospheric radioactive debris. Tellus 18, 316–328 (1966).

Martell, E. A. The size distribution and interaction of radioactive and natural aerosols in the stratosphere. Tellus 18, 486–498 (1966).

Telegadas, K. The seasonal stratospheric distribution of plutonium-238 and strontium-90, March through November 1967. Report HASL-204 (US Atomic Energy Commission, Washington, 1969).

Krey, P. W. & Krajewksi, B. T. Comparison of atmospheric transport model calculations with observations of radioactive debris. J. Geophys. Res. 75, 2901–2908 (1970).

Hirose, K. et al. Annual deposition of Sr-90, Cs-137 and Pu-239,240 from the 1961-1980 nuclear explosions: a simple model. J. Meteor. Soc. Japan 65, 259–277 (1987).

Hall, T. M. & Waugh, D. W. Stratospheric residence time and its relationship of mean age. J. Geophys. Res. 105, 6773–8782 (2000).

Corcho Alvarado, J. A. et al. Anthropogenic radionuclides in atmospheric air over Switzerland during the last few decades. Nature Com. 5, 3030 doi: 10.1038/ncomms4030 (2014).

Holm, E., Rioseco, J. & Pettersson, H. Fallout of transuranium elements following the Chernobyl accident. J. Radioanal. Nucl. Chem. 156, 183–200 (1992).

Livingston, H. D., Schneider, D. L. & Bowen, V. T. 241Pu in the marine environment by a radiochemical procedure. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 25, 361–367 (1975).

Kelley, J. M., Bond, L. A. & Beasley, T. M. Global distribution of Pu isotopes and 237Np. Sci. Total Environ. 237/238, 483–500 (1999).

Koide, M. et al. The 240Pu/239Pu ratio, a potential geochronometer. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 72, 1–8 (1985).

Krey, P. W. et al. [Mass isotopic composition of global fall-out plutonium in soil]. Transuranium Nuclides in the Environment [671–678] (IAEA, Vienna, 1976).

Hisamatsu, S. & Sakanoue, M. Determination of transuranium elements in a so-called “Bikini Ash” sample and in marine sediment samples collected near Bikini atoll. Health Phys. 35, 301–307 (1978).

Diamond, H. et al. Heavy isotope abundances in “Mike” thermonuclear device. Phys. Rev. 119, 2000–2004 (1961).

Koide, M. & Goldberg, E. D. 241Pu/239+240Pu ratios in polar glaciers. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 54, 239–247 (1981).

Komura, K., Sakanoue, M. & Yamamoto, M. Determination of 240Pu/239Pu ratio in environmental samples based on the measurement of LX/X-ray activity ratio. Health Phys. 46, 1213–1219 (1984).

Muramatsu, Y. et al. Measurement of 240Pu/239Pu isotopic ratios in soils from the Marshall islands using ICP-MS. Sci. Total. Environ. 278, 151–159 (2001).

Hardy, E. P. Plutonium in soil northwest of the Nevada test site. Report HASL-306 (US Atomic Energy Commission, Washington, 1976).

Hicks, H. G. & Barr, D. W. Nevada test site fallout atom ratios: 240Pu/239Pu and 241Pu/239Pu. Report UCRL-53499/1 (Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory,Livermore, 1984).

Yamamoto, M., Tsumura, A., Katayama, Y. & Tsukatani, T. Plutonium isotopic composition in soil from the former Semipalatinsk nuclear test site. Radiochim. Acta 72, 209–215 (1996).

International Atomic Energy Agency, IAEA, Summary Report on the Post-accident Review Meeting on the Chernobyl Accident. Safety Series No. 75-INSAG-I (IAEA, Vienna, 1986).

Lujaniené, G., Aninkevicious, V. & Lujanas, V. Artificial radionuclides in the atmosphere over Lithuania. J. Environ. Radioact. 100, 108–119 (2009).

Povinec, P. P., Hirose, K. & Aoyama, M. Fukushima Accident: Radioactivity Impact on the Environment (Elsevier, New York, 2013).

Zheng, J. et al. Isotopic evidence of plutonium release into the environment from the Fukushima DNPP accident. Sci. Rep. 2, 304 (2012).

Environmental Measurements Laboratory, EML, EML Databases and Sample Archives. (1999) Available at: http://www.wipp.energy.gov/NAMP/EMLLegacy/databases.htm. (Accessed: 5th May 2015).

Leifer, R. & Juzdan, Z. R. The High Altitude Sampling Program: Radioactivity in the Stratosphere. Final Report EML-458 (US Department of Energy, New York, 1986).

Hirose, K. & Sugimura, Y. Plutonium in the surface air in Japan. Health Phys. 46, 1281–1285 (1984).

Hirose, K. & Sugimura, Y. Plutonium isotopes in the surface air in Japan: Effect of Chernobyl accident. J. Radioanal. Nucl. Chem. Articles 138, 127–138 (1990).

Wershofen, H. & Arnold, D. Radionuclides in ground-level air in Braunschweig – report of the PTB trace survey station from 1998 to 2003. Radioaktivität PTB-Ra-45 (Physikalische - Technische Bundesanstalt, Braunschweig, 2005).

Playford, K., Toole, J. & Adsley, I. Radioactive fallout in air and rain: results to the end of 1991. Report DOE/RAS/93.003 (Department of the Environment, London, 1993).

Pan, V. & Stevenson, K. A. Temporal variation analysis of plutonium baseline concentration in surface air from selected sites in continental US. J. Environ. Radioact. 32, 239–257 (1996).

Rosner, G. & Winkler, R. Long-term variation (1986-1998) of post-Chernobyl 90Sr, 137Cs, 238Pu and 239,240Pu concentrations in air, depositions to ground, resuspension factors and resuspension rates in south Germany. Sci. Total Environ. 273, 11–25 (2001).

Chamizo, E. et al. Measurement of plutonium isotopes, 239Pu and 240Pu, in air-filter samples from Seville (2001–2002). Atmos. Environ. 44, 1851–1858 (2010).

Krey, P. W. Atmospheric burnup of a plutonium-238 generator. Science 156, 769–771 (1968).

Holland, W. D. Final report of studies of Pu-238 debris particles from the SNAP-9A satellite failure of 1964. Tracerlab Report 6006 (US Atomic Energy Commission, New York, 1968).

Hirose, K. et al. [Long-term trends of plutonium fallout observed in Japan]. Plutonium in the Environment [ Kudo, A. (ed.)] [251-256] (Elsevier, : New York,, 2001).

Hirose, K. et al. Analysis of 50 years records of atmospheric deposition of long-lived radionuclides in Japan. Appl. Radiat. Isot. 66, 1675–1678 (2008).

Pham, M. K. et al. Dry and wet deposition of 7Be, 210Pb and 137Cs in Monaco air during 1998-2010: Seasonal variations of deposition fluxes. J. Environ. Radioact. 120, 45–57 (2013).

Sýkora, I. et al. Resuspension processes control variations of 137Cs activity concentrations in the ground-level air. J. Radioanal. Nucl. Chem. 293, 595–599 (2012).

Masson, O., Piga, D., Gurriaran, R. & D’Amico, D. Impact of an exceptional Saharan dust outbreak in France: PM10 and artificial radionuclides concentrations in air and in dust deposit. Atmos. Environ. 44, 2478–2486 (2010).

Pham, M. K. et al. Temporal changes of 7Be, 137Cs and 210Pb activity concentrations in surface air at Monaco and their correlation with meteorological parameters. J. Environ. Radioact. 102, 1045–1054 (2011).

Levin, I., Kromer, B. & Hammer, S. Atmospheric Δ14CO2 trend in Western European background air from 2000 to 2012. Tellus B,65, 20092 (2013).

Knippertz, P. & Todd, M. C. Mineral dust aerosols over the Sahara: Meteorological controls on emission and transport and implications for modeling. Rev. Geophys. 50, RG1007 (2012).

Lee, H. N. et al. Global model simulations of the transport of Asian and Sahara dust: total deposition of dust mass in Japan. Water, Air and Soil Pollution 169, 137–166 (2006).

Igarashi, Y. et al. What anthropogenic radionuclides (90Sr and 137Cs) in atmospheric deposition, surface soils and Aeolian dusts suggest for dust transport over Japan. Water, Air and Soil Pollution: Focus 5, 51–69 (2005).

Fujiwara, H. et al. Deposition of atmospheric 137Cs in Japan associated with the Asian dust event of March 2002. Sci. Total Environ. 384, 306–315 (2007).

Lee, S. H. et al. Recent inputs and budgets of 90Sr, 137Cs, 239,240Pu and 241Am in the northwest Mediterranean Sea. Deep-Sea Res. II 50, 2817–2834 (2003).

Lee, S. H. et al. Radionuclides in the air over Monaco. J. Radioanal. Nucl. Chem. 254, 445–453 (2002).

Pham, M. K. et al. Deposition of Saharan dust in Monaco rain 2001-2002: radionuclides and elemental compositions. Physica Scripta T118, 14–17 (2005).

Gobbi, G. P., Barnaba, F. & Ammannato, L. The vertical distribution of aerosols, Saharan dust and cirrus clouds at Rome (Italy) in the year 2001. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 4, 351–359 (2004).

Uno, I. et al. Asian dust transported one full circuit around the globe. Nature Geosci. 2, 557–560 (2009).

Ansmann, A. et al. Long-range transport of Saharan dust to northern Europe: The 11 – 16 October 2001 outbreak observed with EARLINET. J. Geophy. Res. 108, D24, 4783 (2003).

Kishcha, P. et al. Vertical distribution of Saharan dust over Rome (Italy): Comparison between 3-year model predictions and lidar soundings. J. Geophys. Res. 110, D06208 (2005).

Tegen, I., Schepanski, K. & Heinold, B. Comparing two years of Saharan dust source activation obtained by regional modelling and satellite observations. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 13, 2381–2390 (2013).

Amiro, B. D., MacPherson, J. I. & Desjardins, R. L. BOREAS flight measurements of forest-fire effects on carbon dioxide and energy fluxes. Agric. For. Meteorol. 96, 199–208 (1999).

Johansen, M. P., Hakonson, T. E., Ward-Whicker, F. & Breshears, D. D. Pulsed redistribution of a contaminant following forest fire. J. Environ. Quality 32, 2150–2157 (2003).

Lujaniené, G. et al. An investigation of changes in radionuclide carrier properties. J. Environ. Radioact. 35, 71–90 (1997).

Wotawa, G. et al. Inter- and intra-continental transport of radioactive cesium released by boreal forest fires. Geophys. Res. Lett. 33, L12806, doi: 10.1029/2006GL026206 (2006).

Guan, H. et al. A multi-decadal history of biomass burning plume heights identified using aerosol index measurements. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 10, 6461–6469 (2010).

Bourcier, L. et al. Experimental evidence of biomass burning as a source of atmospheric 137Cs at Puy de Dome (1465 m a.s.l.), France. Atmos. Environ. 44, 2280–2286 (2010).

Strode, S. A. et al. Emission and transport of cesium-137 from boreal biomass burning in the summer of 2010. J. Geophys. Res. 117, D09302, doi: 10.1029/2011JD017382 (2012).

Self, S., Zhao, J. X., Holasek, R. E., Torres, R. C. & King, A. J. The atmospheric impact of the 1991 Mount Pinatubo eruption. (1999) Available at: http://pubs.usgs.gov/pinatubo/self/. (Accessed: 4th May 2015).

Stone, R. S., Keys, J. & Dutton, E. G. Properties and decay of stratospheric aerosols in the Arctic following the 1991 eruptions of Mount Pinatubo. Geophys. Res. Lett. 20, 2539–2362 (1993).

Kierepko, R. et al. Plutonium traces in atmospheric precipitation and in aerosols from Krakow and Bialystok. Radiochim. Acta 4-5, 253–255 (2009).

Kierepko, R. et al. Plutonium isotopes in the atmosphere of Central Europe: isotopic composition and time evolution vs. circulation factors. INP Preprint (Institute of Nuclear Physics, Krakow, 2015).

Hirose, K., Dokiya, Y. & Sugimura, Y. Concentration and behavior of particulate chloride in the surface air at Tsukuba. Japan. Pap. Meteor. Geophys. 34, 31–38 (1983).

Masson, O. et al. Tracking of airborne radionuclides from the damaged Fukushima Dai-Ichi Nuclear Reactors by European Networks. Environ. Sci. Technol. 45, 7670–7677 (2011).

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge a long-term collaboration with colleagues from Sophia University (Tokyo), Meteorological Research Institute (Tsukuba), Comenius University (Bratislava) and International Atomic Energy Agency (Monaco). PPP acknowledges the financial support of the International Atomic Energy Agency (project #SLR0/008) and the EU Research and Development Operational Program funded by the ERDF (Project #26240220004).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

K.H. wrote the first draft of the text and prepared figures. P.P.P. contributed to the data interpretation and finalization of the paper. Both authors reviewed the final version of the manuscript.

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Hirose, K., Povinec, P. Sources of plutonium in the atmosphere and stratosphere-troposphere mixing. Sci Rep 5, 15707 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep15707

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/srep15707

This article is cited by

-

Natural and anthropogenic radionuclides on aerosols in Bratislava air

Journal of Radioanalytical and Nuclear Chemistry (2020)

-

New ultra-sensitive radioanalytical technologies for new science

Journal of Radioanalytical and Nuclear Chemistry (2018)

-

Can 129I track 135Cs, 236U, 239Pu, and 240Pu apart from 131I in soil samples from Fukushima Prefecture, Japan?

Scientific Reports (2017)

-

Source and long-term behavior of transuranic aerosols in the WIPP environment

Environmental Science and Pollution Research (2016)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.