Abstract

Rechargeable ion-batteries, in which ions such as Li+ carry charges between electrodes, have been contributing to the improvement of power-source performance in a wide variety of mobile electronic devices. Among them, Mg-ion batteries are recently attracting attention due to possible low cost and safety, which are realized by abundant natural resources and stability of Mg in the atmosphere. However, only a few materials have been known to work as rechargeable cathodes for Mg-ion batteries, owing to strong electrostatic interaction between Mg2+ and the host lattice. Here we demonstrate rechargeable performance of Mg-ion batteries at ambient temperature by selecting TiSe2 as a model cathode by focusing on electronic structure. Charge delocalization of electrons in a metal-ligand unit through d-p orbital hybridization is suggested as a possible key factor to realize reversible intercalation of Mg2+ into TiSe2. The viewpoint from the electronic structure proposed in this study might pave a new way to design electrode materials for multivalent-ion batteries.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

At present, rechargeable ion batteries have become one of the key systems for energy storage. In particular, lithium-ion batteries have been widely applied for most portable electronic devices as power sources. However, rechargeable batteries of further safety and low cost are recently being required for large scale applications, such as power sources of smart power grids and electric vehicles. Rechargeable magnesium-ion batteries are considered as one potential solution1,2,3,4,5. Mg-metal, which might be used as a dendrite-free anode6,7, is stable in ambient atmosphere and abundant in the earth crust compared with Li-metal. In addition, the specific volumetric capacity of Mg reaches 3833 mAh/cm3, which is higher than that of Li (2046 mAh/cm3), due to the bivalency of Mg-ion.

On the other hand, the development of Mg-ion batteries has been limited because of difficulties in selecting suitable cathode materials. The strong electrostatic interaction between bivalent Mg-ions and host lattices often causes slow solid state diffusion of Mg2+ within the local crystal structure and prevents reversible insertion/extraction of Mg2+. In the past years, various kinds of materials have been proposed as candidates for cathodes of Mg-ion batteries, such as Chevrel phases Mo6X8 (X = S, Se)8,9, o-Mo9Se1110, TiS2 nanotube11, graphene-like MoS212, WSe2 nanowire13, MgMSiO4 (M = Fe, Mn, Co)14,15,16,17,18,19,20, MgFePO4F21, FePO422, MnO223,24, V2O5 xerogel/thin film25,26,27, organic compounds28,29,30, Prusian Blue analogues31,32. However, in most cases, Mg-ion batteries could only function by assistance of nanoscale morphology of electrode materials11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,23,24,25 or screening of the electrostatic interaction by solvent species such as aqueous ions31,32. One exception is Chevrel phases, Mo6X8 (X = S, Se). Electrochemical performance of micro-crystal Mo6X8-electrodes is reported to be comparable with that of nano-crystal at ambient temperature9. In the Chevrel phases, delocalized electronic orbitals of Mo6X8, in which two electrons are accommodated by cluster units of Mo6 and the variation of formal charge on individual Mo atom are suppressed to only 1/3e, are suggested to possibly moderate local structural deformation induced by the electrostatic interaction between Mg2+ and the local lattice, in which extra electrons are accommodated4,33. As a consequence of charge distribution over multiple atoms, the charge imbalance during the insertion of bivalent ions is supposed to be easily relieved in the Chevrel phase. In the recent studies, other compounds with clustered structures, such as o-Mo9Se11 and C60, are also reported to display reversible Mg-ion insertion reactions10,30. Thus, systems with delocalized electrons over multiple atoms might be expected as good candidates for rechargeable cathodes of Mg-ion batteries.

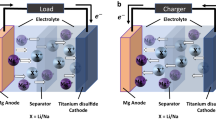

In this study, we have focused on the possible effect of electronic delocalization in metal-ligand units through orbital hybridization in transition-metal chalcogenides. When the atomic orbitals hybridize strongly between transition-metals and chalcogens, the electronic wave function of transition-metal chalcogenide spreads on both constituent atoms34 (See Figure S1a); The charge density of the introduced electrons should distribute over metal-ligand units as schematically shown in Fig. 1a. On the other hand, in a system with weak orbital hybridization, the electrons should be accommodated only in the transition metal orbitals as displayed in Fig. 1b (See also Figure S1b). In this study, taking into account that the degree of orbital hybridization is enhanced in the case that the difference between energy levels of atomic orbitals is small35, layered TiSe2 (Fig. 1c) has been selected as a candidate material based on the energy diagram for atomic d-orbitals of transition metals and p-orbitals of chalcogens (Fig. 1d)36. As displayed in Fig. 1d, since the energy levels of valence atomic orbitals in TiSe2, 3d-orbital of Ti and 4p-orbital of Se, are close to each other, the hybridized electronic structure is expected around Fermi energy. In fact, the conducting properties, which could be ascribed to the delocalized electronic structure by orbital hybridization, have been confirmed in TiSe2 around room temperature37. Here, we report the rechargeable performance of TiSe2 with d-p orbital hybridization as a cathode of Mg-ion batteries.

(a) A schematic illustration of charge distribution in the electronic state with strong d-p hybridization. Electrons are accommodated in the delocalized state, which extends over transition metal and ligand atoms as schematically shown by the red framework. (b) A schematic drawing of charge distribution in the electronic state with weak d-p hybridization. Electrons are accommodated only in the localized state of transition metal. (c) The crystal structure of 1T-TiSe2. (d) Energy diagram of atomic orbitals (Appendix A in Ref. 36). Red circles, blue squares and orange triangles represent the energy levels of 3d-, 4d- and 5d-orbitals of each transition metal, respectively. The horizontal lines display the energy level position of O 2p-orbital, S 3p-orbital and Se 4p-orbital, respectively. (e) The powder X-ray diffraction pattern (XRD) of the TiSe2 sample. The inset shows the image of scanning electronic microscopy (SEM) of the TiSe2 sample.

Results

The powder X-ray diffraction (XRD) result indicates that TiSe2 used in this study takes a 1T-type structure (a = 3.5393(2) Å and c = 6.0103(3) Å) with a space group P3-m1 (Fig. 1e) as reported in the previous study38. As shown in Fig. 1c, the 1T-type structure consists of successive Se-Ti-Se sandwich slabs, which are separated by the van der Waals gap. The sample was also checked by Scanning Electronic Microscopy (SEM), showing that TiSe2 has a particle size around 10 μm (Fig. 1e).

The orbital hybridization in TiSe2 was confirmed by first principle calculation. The energy band dispersion and density of states (DOS) are shown in Fig. 2a,b, respectively. The calculated electronic band structure indicates that 1T-TiSe2 is a semimetal with a small overlap between the valence band maximum at the Brillouin zone (BZ) center, Γ-point and the conduction band minimum at the BZ boundary, L-point (Fig. 2a). This electronic band structure is consistent with the previous studies by Ab initio band structure calculation39 and angle resolved photoemission measurements40,41. The orbital components of valence and conduction bands indicate the existence of d-p orbital hybridization. As shown in the partial DOS of TiSe2 (see Fig. 2b), the electronic states around the Fermi level (EF) consist of both 3d-orbital of Ti and 4p-orbital of Se. In this situation, since the wave function spreads over both Ti- and Se-atoms as shown in Fig. 1a, introduced electrons in the discharge process of TiSe2 are expected to be accommodated into a “cluster-like” electronic state.

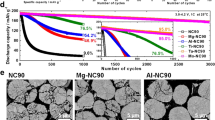

The Mg-ion battery with a TiSe2 cathode shows reversible electrochemical charge/discharge performance at ambient temperature. Figure 3a displays a typical voltage profile of the coin cell at 25 °C, which consists of a TiSe2-based cathode, a magnesium metal anode and 0.25 M Mg(AlCl2EtBu)2/THF electrolyte solution, in which formation of the passivation film is suppressed thus Mg is reversibly deposited/dissolved on the anode8. The derivative of the capacity (Q) with respect to the voltage (V), dQ/dV, is plotted in Fig. 3b. The redox peaks are observed in the cathodic process (at 0.9 V vs. Mg/Mg2+) and anodic process (at 1.2 V vs. Mg/Mg2+), respectively. This result indicates that TiSe2 can work as a rechargeable electrode material in the Mg-ion-battery system.

(a) The charge/discharge curve (on the second cycle) of the Mg-ion battery cell with TiSe2 measured at 25 °C. (b) The derivative of the capacity (Q) in Fig. 3(a) with respect to the voltage (V), dQ/dV. (c) Cycle performance of the Mg-ion battery cell with TiSe2 for capacity. The inset shows the charge/discharge curves on each cycle.

Figure 3c shows cyclability of the TiSe2 cathode in the first 50 cycles at 25 °C. The specific capacity is kept at the values around 110 mAh/g during the whole cycling. Assuming that the redox species is Ti4+/Ti3+, the average specific capacity observed, 108 mAh/g, is about 83% of the theoretical capacity (130 mAh/g). The specific capacity of TiSe2 is comparable with that of Mo6S8 (~100 mAh/g9, Chevrel phase), which is the prototype cathode material of Mg-ion batteries.

Structural variation after the discharge process was traced by measuring ex situ XRD patterns of MgxTiSe2. XRD measurements were performed for selected compositions (x = 0, 0.2, 0.4, 0.5). As shown in Fig. 4a, the XRD pattern of TiSe2 is maintained after the discharge process. In the XRD pattern of discharged cathode, a small broad peak appears around 47°, which are likely to be assigned to those of Se. Selenium phase seems to be produced by some decomposition of partial cathode, which might be the reason of capacity fading during the cycling. Focusing on the 00l peaks (l = 1, 2, 3 and 4), all of them gradually shift to the lower angles. This result indicates that Mg2+ is intercalated into the van der Waals gap between TiSe2 layers in the crystal lattice. During the Mg-ion intercalation, the lattice constant of c-axis, which was estimated from the XRD patterns in Fig. 4a, increases from 6.0103(3) Å (x = 0) to 6.072(3) Å (x = 0.5) (Fig. 4b). The structural reversibility was also confirmed by the ex situ XRD measurements. Figure 4c displays the XRD patterns after discharge/charge process. The 004 peak shifts to a lower angle in the discharged state (x = 0.48) from its angle in the initial state (x = 0), while it shifts back around the initial angle in the charged state (x = 0.05). Mg concentrations in TiSe2 cathode are confirmed to be x = 0.46 for the discharged state (x = 0.48 from the electrochemical test) and x = 0.12 for the charged state (x = 0.05 from the electrochemical test) by inductively coupled plasma atomic emission spectrometry (ICP-AES), respectively. The concomitant variation of Mg concentrations in the discharge/charge process seems to support reversible expansion/contraction picture of the crystal lattice along c-axis in TiSe2 by intercalation/deintercalation of Mg2+ into/from the van der Waals gap.

(a) Powder XRD of MgxTiSe2 (x = 0, 0.2, 0.4 and 0.5). The ex situ XRD measurements were carried out after the discharging processes. (b) Mg-content (x) dependence of unit cell parameter of c-axis. (c) 004 peak shift after discharging (x = 0.48; orange line) and charging processes (x = 0.05; red line). The peak in the initial state (x = 0) is represented by the blue line.

Discussion

So far, materials research on cathodes of Mg-ion batteries has been independently performed with emphasis on the crystal structure of each target material in most cases. On the other hand, by introducing the viewpoint based on electronic structures as in this study on TiSe2, a common feature seems to appear in the previously reported cathode materials of Mg-ion batteries, such as Mo6X8 (X = S, Se)8,9, TiS211, MoS212 and WSe213. The common feature is that orbital hybridization is expected between the valence atomic orbitals of constituent atoms in these materials, which are d-orbital of transition metal atoms and p-orbital of chalcogen atoms, due to the close energy levels (Fig. 1d). Intriguingly, such small energy difference between transition metal’s d-orbital and ligand’s p-orbital can be found not only in the cathodes of Mg-ion batteries but also in the representative ones of Li-ion batteries; LixTiS242, LixCoO243 and Li1-xMn2O444 (see Fig. 1d). In these cathode materials of Li-ion batteries, d-p orbital hybridization can be confirmed in the electronic structures reported by first principle calculations45,46,47. These facts seem to support the efficacy of electron delocalization in metal-ligand units for improving ion-battery performance through d-p orbital hybridization. In fact, the charge distribution over transition metal and oxygen atoms are pointed out for Li(Co, Al)O2 by first principle calculation48 and are confirmed in LixCoO2 and LixMn2O4 by X-ray spectroscopy49,50.

In the case of selenides, d-p orbital hybridization should be enhanced by high orbitals overlap due to the large 4p-orbital size of Se, compared with oxides or sulfides. Additionally, in TiSe2, the two-dimensionality of ion conducting channels in the van der Waals gap might contribute to suppress the effect of Coulomb repulsion between Mg-ions10. These factors in the TiSe2 cathode might contribute to its reversibility on electrochemical cycling and high specific capacity close to the theoretical value in the Mg-ion battery even with micro-sized electrode. In fact, the Mg-ion battery with another cathode material, 1T-VSe2, where the electronic and crystal structures are similar with those of 1T-TiSe2, also shows rechargeable cathode performance over 60 cycles with kept relatively high capacity of ~110 mAh/g at ambient temperature (Figure S2a, b). In these materials (TiSe2 and VSe2) that can work as reversible Mg-ion battery cathodes in the form of micro-sized particles, further improvement in cyclability and rate capability might be expected by downsizing cathode materials to the nanometric scale as done in graphene-like MoS212 and WSe2 nanowire13.

The viewpoint from electronic structure of cathode materials could draw a guideline for developing high voltage Mg-ion batteries. In general, open circuit voltage of an ion-battery (Voc) is given by difference in electrochemical potentials of electrons between anode (μAe) and cathode (μCe); eVoc = μAe – μCe, where e is magnitude of electron charge51,52. Taking into account that the electrochemical potential of electrons is defined by Fermi level in vacuum and inner-potential, trend of ion-battery voltage could be assessed by difference in Fermi levels between two electrodes in first approximation. Since the Fermi level of cathode is determined by the electronic structure of valence/conduction band, the voltage of battery using same anodes should reflect the energy levels of valence atomic orbitals, which constitute a valence/conduction band. In the case of TiSe2, because the energy levels of Ti 3d-orbital and Se 4p-orbital are located in the shallow energy range compared with late transition metals and oxygen as shown in Fig. 1d, the observed voltage, ~1 V vs. Mg/Mg2+, seems to be a lower value than those of Li-ion batteries with transition metal oxides, such as LixCoO2 and Li1-xMn2O4. In further material research for Mg-ion battery cathodes with improved performance, late transition metal oxides might be good candidates for reaching high voltages cells, because their valence bands consist of atomic orbitals located in the deep energy range. In addition, since selenium is a rare element that may be toxic, developing cathodes of oxides could be desirable from the standpoint of practical use and environmental concerns.

In summary, this study has demonstrated that the Mg-ion battery with a micro-sized TiSe2 cathode shows rechargeable performance at ambient temperature. In TiSe2, reflecting the close energy levels of 3d-orbital of Ti and 4p-orbital of Se, d-p orbital hybridization around the Fermi level was confirmed by first principle calculation. The XRD measurements indicate that Mg-ions are reversibly intercalated into and deintercalated from the van der Waals gap between the TiSe2 layers. We have proposed one possible scenario that the charge delocalization in metal-ligand units by strong d-p orbital hybridization might be one of the key factors, which improve reversible performance of Mg2+-intercalation/deintercalation. Further study based on the electronic structure could open a new way to design cathode materials for Mg-ion and other multivalent ion batteries.

Methods

Sample preparation and electrochemical measurements

The purchased TiSe2 powder (>99%, High Purity Chemicals) was used as a cathode material. Cathodes were fabricated using TiSe2, acetylene black (AB) and polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE) in a mass ratio of 81:9:10. The mixed active material was pressed on a current collector of copper net and dried at 60 °C in vacuum. The amount of active material was approximately 3 ~ 4 mg per cathode. Tests of Mg-ion batteries were performed by 2032-type coin cells, which were assembled in an Ar-filled glove box. These cells consisted of TiSe2 cathodes, magnesium metal anodes and the Mg(AlCl2EtBu)2 electrolyte dissolved at 0.25 mol/dm3 in tetrahydrofuran (THF). The galvanostatic charge/discharge tests were conducted using a potentio-galvanostat (Solartron, 1470E) at 25 °C. Current density dependence of capacity was tested for 5 mA/g, 10 mA/g, 20 mA/g and 50 mA/g, respectively (Fig. S3(a)). Rate capability, which is defined as the capacity ratio to the discharge capacity at 5 mA/g, decreases to ca. 50% at high current density of 50 mA/g (see Fig. S3(b)). The cell voltage in the galvanostatic charge/discharge measurements was cycled between 1.8 V and 0.2 V (vs. Mg/Mg2+) for 50 times by applying a constant current at 5 mA/g. Electrochemical characteristic of TiSe2 in a electrolyte solution other than Mg(AlCl2EtBu)2 /THF was examined through Cyclic voltammetry (CV) measurements with a three-electrode cell. As an electrolyte for CV measurements, Mg(ClO4)2 was dissolved in acetonitorile (AN) at 1 mol/dm3. A magnesium metal and a silver wire, which was put into a solution of 0.01 mol/dm3 AgNO3 and 0.1 mol/dm3 tetrabutylammonium perchlorate in acetonitorile, were employed as a counter electrode and a reference electrode, respectively. In the CV measurement, the potential was scanned between 0 V and –1.5 V (vs. Ag/Ag+) at 0.5 mV/s. In the voltammogram, one peak was clearly observed for both cathodic and anodic processes, respectively (Fig. S4).

Material characterization

Structural characterization of samples was performed to analyze the change of TiSe2 upon cycling by ex situ powder X-ray diffraction (XRD) using a graphite monochromatized Cu Kα radiation source. The particle size of sample was measured by scanning electronic microscopy (SEM). The variation of the Mg concentration in the TiSe2 cathodes after discharge/charge process was traced by quantitative chemical analysis. The atomic ratio of Mg to Ti was determined quantitatively by inductively coupled plasma atomic emission spectrometry (ICP-AES). The electrodes were removed from the cells after the charge/discharge cycling process and rinsed with THF to dissolve out the electrolyte salt in an Ar-filled glove box before the measurements. In the ex situ structural analysis of electrodes, electrochemically prepared electrode samples were measured immediately after being transferred out of the glove box, or sealed with polyethylene-nylon films in an Ar-filled glove box before XRD measurements.

First-principle calculation

First-principle electronic structure calculations were performed by Full-potential Linearized Augmented Plane Wave (FLAPW) method implemented in WIEN2k53 code, under Tran-Blaha modified Becke-Johnson (TB-mBJ) exchange-correlation potential54. Muffin-tin radii for Ti and Se were set to 2.50 and 2.25 a.u., respectively. The first Brillouin zone was divided into 21 × 21 × 10 k-point mesh with 436 irreducible points. No spin polarization was considered. Obtained density of states (DOS) was rescaled to the primitive unit cell.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Gu, Y. et al. Rechargeable magnesium-ion battery based on a TiSe2-cathode with d-p orbital hybridized electronic structure. Sci. Rep. 5, 12486; doi: 10.1038/srep12486 (2015).

References

Saha, P. et al. Rechargeable magnesium battery: Current status and key challenges for future. Prog. Mater. Sci. 66, 1–86 (2014).

Shterenberg, I., Salama, M., Gofer, Y., Levi, E. & Aurbach, D. The challenge of developing rechargeable magnesium batteries. Mrs Bull. 39, 453–460 (2014).

Yoo, H. D. et al. Mg rechargeable batteries: an on-going challenge. Energy Environ. Sci. 6, 2265–2279 (2013).

Levi, E., Gofer, Y. & Aurbach, D. On the Way to Rechargeable Mg Batteries: The challenge of New Cathode Materials. Chem. Mater. 22, 860–868 (2010).

Levi, E., Levi, M. D., Chasid, O. & Aurbach, D. A review on the problems of the solid state ions diffusion in cathodes for rechargeable Mg batteries. J. Electroceram. 22, 13–19 (2009).

Matsui, M. Study on electrochemically deposited Mg metal. J. Power Sources. 196, 7048–7055 (2011).

Ling, C., Banerjee, D. & Matsui, M. Study of the electrochemical deposition of Mg in the atomic level: why it prefers the non-dendritic morphology. Electrochim. Acta. 76, 270–274 (2012).

Aurbach, D. et al. Prototype systems for rechargeable magnesium batteries. Nature. 407, 724–727 (2000).

Aurbach, D. et al. Progress in Rechargeable Magnesium Battery Technology. Adv. Mater. 19, 4260–4267 (2007).

Taniguchi, K., Yoshino, T., Gu, Y., Katsura, Y. & Takagi, H. Reversible electrochemical insertion/extraction of Mg and Li ions for orthorhombic Mo9Se11 with cluster structure. J. Electrochem. Soc. 162, A198–A202 (2015).

Tao, Z.-L., Xu, L.-N., Gou, X.-L., Chen, J. & Yuan, H.-T. TiS2 nanotubes as the cathode materials of Mg-ions batteries. Chem. Commun. 2080–2081 (2004).

Liang, Y. et al. Rechargeable Mg Batteries with Graphene-like MoS2 Cathode and Ultrasmall Mg Nanoparticle Anode. Adv. Mater. 23, 640–643 (2011).

Liu, B. et al. Rechargeable Mg-Ion Batteries Based on WSe2 Nanowire Cathodes. ACS. Nano. 7, 8051–8058 (2013).

Orikasa, Y. et al. High energy density rechargeable magnesium battery using earth-abundant and non-toxic elements. Sci. Rep. 4, 5622 (2014).

Feng, Z., Yang, J., NuLi, Y. & Wang, J. Sol-gel synthesis of Mg1.03Mn0.97SiO4 and its electrochemical intercalation behavior. J. Power Sources. 184, 604–609 (2008).

Feng, Z. et al. Preparation and electrochemical study of a new magnesium intercalation material Mg1.03Mn0.97SiO4 . Electrochem. Commun. 10, 1291–1294 (2008).

NuLi, Y., Yang, J., Wang, J. & Li, Y. Electrochemical Intercalation of Mg2+ in Magnesium Manganese Silicate and Its Application as High-Energy Rechargeable Magnesium Battery Cathode. J. Phys. Chem. C. 113, 12594–12597 (2009).

NuLi, Y., Yang, J., Li, Y. & Wang, J. Mesoporous magnesium manganese silicate as cathode materials for rechargeable magnesium batteries. Chem. Commun. 46, 3794–3796 (2010).

NuLi, Y. et al. MWNT/C/Mg1.03Mn0.97SiO4 hierarchical nanostructure for superior reversible magnesium ion storage. Electrochem. Commun. 13, 1143–1146 (2011).

Zheng, Y. et al. Magnesium cobalt silicate materials for reversible magnesium ion storage. Electrochimica. Acta. 66, 75–81 (2012).

Huang, Z.-D. et al. MgFePO4F as a feasible cathode material for magnesium batteries. J. Mater. Chem. A. 2, 11578–11582 (2014).

Oyama, G., Nishimura, S., Chung, S.-C., Okubo, M. & Yamada, A. Electrochemical Properties of Heterosite FePO4 in Aqueous Mg2+ Electrolytes. Electrochemistry. 82, 855–858 (2014).

Zhang, R. et al. α–MnO2 as a cathode material for rechargeable Mg batteries. Electrochem. Commun. 23, 110–113 (2012).

Rasul, S., Suzuki, S., Yamaguchi, S. & Miyayama, M. High capacity positive electrodes for secondary Mg-ion batteries. Electrochim. Acta. 45, 243–249 (2012).

Imamura, D., Miyayama, M., Hibino, M. & Kudo, T. Mg Intercalation Properties into V2O5 gel/Carbon Composites under High-Rate Condition. J. Electrochem. Soc. 150, A753–A758 (2003).

Inamoto, M., Kurihara, H. & Yajima, T. Electrode Performance of Vanadium Pentoxide Xerogel Prepared by Microwave Irradiation as an Active Cathode Material for Rechargeable Magnesium Batteries. Electrochemistry. 80, 421–422 (2012).

Gershinsky, G., Yoo, H. D., Gofer, Y. & Aurbach, D. Electrochemical and Spectroscopic Analysis of Mg2+ Intercalation into Thin Film Electrodes of Layered Oxides: V2O5 and MoO3 . Langmuir. 29, 10964–10972 (2012).

NuLi, Y., Guo, Z., Liu, H. & Yang, J. A new class of cathode materials for rechargeable magnesium batteries: Organosulfur compounds based on sulfur-sulfur bonds. Electrochem. Commun. 9, 1913–1917 (2007).

Sano, H., Senoh, H., Yao, M., Sakabe, H. & Kibayashi, T. Mg2+ Storage in Organic Positive-electrode Active Material Based on 2,5-Dimethoxyl-1,4-benzoquinone. Chem. Lett. 41, 1594–1596 (2012).

Zhang, R., Mizuno, F. & Ling, C. Fullerenes: non-transition metal clusters as rechargerable magnesium battery cathodes. Chem. Commun. 51, 1108–1111 (2015).

Mizuno, Y. et al. Electrochemical Mg2+ intercalation into a bimetallic CuFe Prussian blue analog in aqueous electrolytes. J. Mater. Chem. A. 1, 13055–13059 (2013).

Wang, R. Y., Wessells, C. D., Huggins, R. A. & Cui, Y. Highly Reversible Open Framework nanoscale Electrodes for Divalent Ion Batteries. Nano Lett. 13, 5748–5752 (2013).

Aurbach, D., Weissman, I., Gofer, Y. & Levi, E. Nonaqueous Magnesium Electrochemistry and Its Application in Secondary Batteries. Chem. Rec. 3, 61–73 (2003).

Saubanère, M., Yahia, M. B., Lebègue, S. & Doublet, M.-L. An intuitive and efficient method for cell voltage prediction of lithium and sodium-ion batteries. Nat. Commun. 5, 5559 (2014).

Cox, P. A. The electronic structure and chemistry of solids (Oxford University Press, 1987).

Harrison, W. A., Electronic structure and the properties of solid [ Dover (ed.)] (Dover Publications, 1989).

Morosan, E. et al. Superconductivity in CuxTiSe2 . Nat. Phys. 2, 544–550 (2006).

Riekel, C. Structure refinement of TiSe2 by neutron diffraction. J. Solid State Chem. 17, 389–392 (1976).

Fang, C. M., Groot, R. A. & Haas, C. Bulk and surface electronic structure of 1T-TiS2 and 1T-TiSe2 . Phys. Rev. B 56, 4455–4463 (1997).

Anderson, O., Manzke, R. & Skibowski, M. Three-dimensional and Relativistic Effects in layered 1T-TiSe2 . Phys. Rev. Lett. 55, 2188–2191 (1985).

Pillo, Th. et al. Photoemission of bands above the Fermi level: The excitonic insulator phase transition in 1T-TiSe2 . Phys. Rev. B 61, 16213–16222 (2000).

Whittingham, M. S. Electrical Energy Storage and Intercalation Chemistry. Science. 192, 1126–1127 (1976).

Mizushima, K., Jones, P. C., Wiseman, P. J. & Goodenough, J. B. LixCoO2 (0 < x ≤ 1): A new cathode material for batteries of high energy density. Mat. Res. Bull. 15, 783–789 (1980).

Tarascon, J. M., Wang, E., Shokoohi, F. K., McKinnon, W. R. & Colson, S. The Spinel Phase of LiMn2O4 as a Cathode in Secondary Lithium Cells. J. Electrochem. Soc. 138, 2859–2864 (1991).

Fang, C. M., de Groot, R. A. & Haas, C. Bulk and surface electronic structure of 1T-TiS2 and 1T-TiSe2 . Phys. Rev. B, 56, 4455–4463 (1997).

Czyżyk, M. T., Potze, R. & Sawatzky, G. A. Band-theory description of high-energy spectroscopy and the electronic structure of LiCoO2 . Phys. Rev. B 46, 3729–3735 (1992).

Grechnev, G. E., Ahuja, R., Johansson, B. & Eriksson, O. Electronic structure, magnetic and cohesive properties of LixMn2O4: Theory. Phys. Rev. B 65, 174408 (2002).

Ceder, G. et al. Identification of cathode materials for lithium batteries guided by first-principles calculations. Nature 392, 694–696 (1998).

Mizokawa, T. et al. Role of Oxygen Holes in LixCoO2 Revealed by Soft X-ray Spectroscopy. Phys. Rev. Lett. 111, 056404 (2013).

Suzuki, K. et al. Extracting the Redox Orbitals in Li Battery Materials with High-Resolution X-Ray Compton Scattering Spectroscopy. Phys. Rev. Lett. 114, 087401 (2015).

Delmas, C. et al. Lithium batteries: a new tool in solid state chemistry. Int. J. Inorg. Mater. 1, 11–19 (1999).

Goodenough, J. B. & Kim, Y. Challenges for Rechargeable Li Batteries. Chem. Mater. 22, 587–603 (2010).

Blaha, P., Schwarz, K., Madsen, G. K. H., Kvasnicka, D. & Luitz, J. WIEN2k. An augmented plane wave plus local orbitals program for calculating crystal properties (Vienna University of Technology, Austria, 2001).

Tran, F., Blaha, P. & Schwarz, K. Band gap calculations with Becke–Johnson exchange potential. J. Phys.: Condens. Matter 19, 196208 (2007).

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge experimental support from Ube Industries, Ltd. We thank S. Nishimura for his advices on the experimental technique. The present work was performed under management of “Elements Strategy Initiative for Catalysts & Batteries (ESICB)” supported by MEXT program “Elements Strategy Initiative to Form Core Research Center” (since 2012), MEXT; Ministry of Education Culture, Sports, Science and Technology, Japan.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.G. performed the sample preparation, characterization and electrochemical measurements. Y.K. contributed to the first principle calculation. T.Y. assisted in the experiments. H.T. co-supervised the project. K.T. conceived the experiments, carried out the data analysis and supervised the project. All authors discussed the results and commented on the manuscript.

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Gu, Y., Katsura, Y., Yoshino, T. et al. Rechargeable magnesium-ion battery based on a TiSe2-cathode with d-p orbital hybridized electronic structure. Sci Rep 5, 12486 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep12486

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/srep12486

This article is cited by

-

Intercalation as a versatile tool for fabrication, property tuning, and phase transitions in 2D materials

npj 2D Materials and Applications (2021)

-

Anomalous orbital structure in two-dimensional titanium dichalcogenides

Scientific Reports (2019)

-

Reversible magnesium and aluminium ions insertion in cation-deficient anatase TiO2

Nature Materials (2017)

-

Fast kinetics of magnesium monochloride cations in interlayer-expanded titanium disulfide for magnesium rechargeable batteries

Nature Communications (2017)

-

Beyond Li-ion: electrode materials for sodium- and magnesium-ion batteries

Science China Materials (2015)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.