Abstract

Ultrafine copper nanoparticles (Cu NPs) within porous silica nanospheres (Cu@SiO2) were prepared via a simple one-pot synthetic route in a reverse micelle system and characterized by SEM, TEM, EDX, XRD, N2 adsorption-desorption, CO-TPD, XPS and ICP methods. The characterized results show that ultrafine Cu NPs with diameter of around 2 nm are effectively embedded in the center of well-proportioned spherical SiO2 NPs of about 25 nm in diameter. Compared to commercial SiO2 supported Cu NPs, SiO2 nanospheres supported Cu NPs and free Cu NPs, the synthesized core-shell nanospheres Cu@SiO2 exhibit a superior catalytic activity for the hydrolytic dehydrogenation of ammonia borane (AB, NH3BH3) and hydrazine borane (HB, N2H4BH3) under ambient atmosphere at room temperature. The turnover frequencies (TOF) for the hydrolysis of AB and HB in the presence of Cu@SiO2 nanospheres were measured to be 3.24 and 7.58 mol H2 (mol Cu min)−1, respectively, relatively high values for Cu nanocatalysts in the same reaction. In addition, the recycle tests show that the Cu@SiO2 nanospheres are still highly active in the hydrolysis of AB and HB, preserving 90 and 85% of their initial catalytic activity even after ten recycles, respectively.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Hydrogen is a globally accepted clean energy. The efficient and safe storage and release of hydrogen is the major technical challenge of utilizing hydrogen as an alternative energy carrier1,2. Chemical storage materials with high hydrogen content and low molecular weight are expected as potential hydrogen sources. Particularly, boron- and nitrogen- (B-N) based compounds including ammonia borane (NH3BH3, AB) and hydrazine borane (N2H4BH3, HB) have received much attention3,4,5,6,7. Ammonia borane, the simplest B-N compound, has been an attractive candidate for chemical hydrogen storage material owing to its high hydrogen capacity (19.6 wt%) and low formula weight (30.9 g/mol)8,9,10,11. The closely related compound HB contains 15.4 wt% of hydrogen, which is higher than the 2015 target of U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) (9 wt% of hydrogen) and regards as another B-N compound for chemical hydrogen storage application12,13,14. In general, hydrogen stored in AB and HB can be released through solvolysis (hydrolysis and methanolysis) in solution8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18 and thermal dehydrogenation in solid state19,20. The recent studies in HB indicated that the extent of hydrogen generation can be increased up to 5 mol H2 per mol HB via both hydrolysis of the group BH3 and decomposition of the group of N2H4 by using Ni-Pt and Ni-Rh nanocatalysts at 323 K, which enhances the importance of the use of HB in the chemical hydrogen storage21,22,23,24,25. As the thermal dehydrogenation requires high temperature and power consumption, catalytic hydrolysis of AB and HB has particularly attracted a great of research interests. In the presence of suitable catalysts, hydrolysis of AB (eqn.1) and HB (eqn.2) can be achieved under ambient atmosphere at room temperature.

So far, lots of metal-based catalysts have been tested for hydrogen generation from the hydrolysis of AB26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41 and HB12,13,14. Copper is an abundant element in the earth's crust. However, the Cu nanocatalysts are still not well-pleasing for hydrolysis of AB and HB up to now14,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41. Therefore, it is of profound interest to achieve the high activity and long reusability of Cu nanocatalysts.

For practical application, the synthesis of metal-based nanocatalyst is an important topic in heterogeneous catalysis. However, most of these catalysts in nano-size are easily aggregated, leading to the loss of the catalytic activity and reusability performance. In recent years, synthesis of metal NPs into a porous material or within a core-shell system has attracted much attention due to the possibility of obtaining monodisperse and ultrafine metal NPs42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52. Moreover, the agglomerate of metal NPs can be avoided, even under harsh reaction condition, because of the confinement effects in those materials43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52. Especially, metal NPs embedded in the silica shells have received tremendous attention in many fields, such as catalysis44,45,46,47,48, absorbents49, drug delivery50, photonics51 and magnetics52. Various approaches have been used to synthesize such materials, however, besides the tedious assembly procedures, the sizes of metal NPs in silica shells are often limited by the pre-synthesized metal colloids methods, resulting in the difficulty to prepare and assemble metal core NPs smaller than 10 nm inside the silica nanoshell53.

Herein, for the first time, we report a simple one-pot protocol for preparing of ultrafine copper nanoparticles embedded in porous silica nanospheres by a reverse micelle method under ambient atmosphere at room temperature. The obtained core-shell nanospheres can hinder the interaction between Cu NPs core and completely avoid the Cu NPs aggregate through the protection of porous silica shell. Especially, the as-synthesized Cu@SiO2 nanospheres show a superior catalytic activity, in comparison to the commercial SiO2 supported Cu NPs (Cu/Commercial SiO2), SiO2 nanospheres supported Cu NPs (Cu/SiO2) and free Cu NPs for the hydrolytic dehydrogenation of AB and HB at room temperature. The activation energy and reusability of the synthesized Cu@SiO2 core-shell nanospheres for the hydrolysis of AB and HB have also been studied.

Results

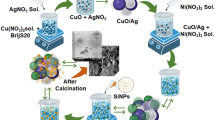

The synthetic process for preparing Cu@SiO2 core-shell nanospheres was illustrated in Fig. 1. Briefly, aqueous solution of copper(II) chloride dihydrate (CuCl2·2H2O), a precursor for metal nanoparticles, was first added into the cyclohexane solution of polyethylene glycolmono-4-nonylphenyl ether (NP-5) in the step of water-in-oil (w/o) reverse micelle formation45,46,47,48,49. As shown in Figure 1, the amount of CuCl2 solution could be contained in micelle particles. When tetraethylorthosilicate (TEOS) was added to this system, the hydrolysis of TEOS by aqueous NH3·H2O would proceed on the interface between water and oil, resulting in the encapsulation of copper precursor in silica shell. After washing with methanol, the copper precursor embedded in the SiO2 nanospheres were reduced to copper nanoparticles (Cu@SiO2) using AB as a reducing agent.

The scanning electron microscope (SEM) image for the Cu@SiO2 nanospheres is shown in Fig. 2(a,b). SEM images show that the Cu@SiO2 samples prepared by the one-pot synthetic route in a reverse micelle system are quite uniform nanospheres. The morphology and size of the obtained sample was further characterized by transmission electron microscopy (TEM). As shown in Fig. 2(c,d,f), the sample consists of uniform size and well-proportioned spherical particles, in good agreement with SEM observation (Fig. 2(a,b)). The core-shell nanostructures of the as-synthesized Cu@SiO2 sample are easy to distinguish that ultrafine Cu NPs (dark spots in Fig. 2f) with diameter of around 2 nm are effectively embedded in the center of well-proportioned spherical SiO2 NPs of about 25 nm in diameter, confirmed by the HAADF-STEM observation (Fig. 2e). The EDX spectra of the Cu@SiO2 nanospheres in Fig. S2 shows the Kα peaks corresponding to O (0.53 keV), Si (1.75 keV), Cu (0.93, 8.03, 8.92 keV) elements and Ni signals (7.49 keV) from the TEM grids. The EDX analysis further confirms that monodisperse and ultrafine Cu NPs core is embedded within the SiO2 shell. In contrast, the large agglomerate/aggregate Cu NPs were observed in Cu/Commercial SiO2, Cu/SiO2 and free Cu NPs (Fig. 3), which may lead to a decrease in the catalytic activity and reusability (vide infra).

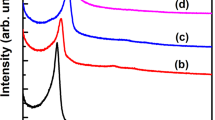

The as-synthesized catalysts were analyzed by powder X-ray diffraction (XRD). As shown in Fig. 4, the strong and broad peak in the range of 2θ = 15–35° can be assigned to amorphous silica with no diffraction peaks to Cu NPs, probably because Cu NPs within SiO2 are too small (Fig. 2) and/or the Cu content is too low (2.2 wt%). However, for Commercial SiO2 supported Cu NPs and free Cu NPs (Fig. 4), the diffraction peaks (2θ) at 43.34°, 50.47° and 74.17° are attributed to the (111), (200) and (220) planes of Cu, respectively, which can be indexed undisputedly to cubic Cu (JCPDS No. 04-0836). Additionally, the XPS spectrum of Cu@SiO2 core-shell nanospheres shows two prominent peaks at 932.5 and 952.5 eV which are readily assigned to Cu2p3/2 and Cu 2p1/2 (Fig. 2), respectively, indicating that Cu(II) NPs was reduced to Cu(0) NPs.

A nitrogen adsorption-desorption study shows that the Brunauer-Emmett-Teller (BET) surface area of the Cu@SiO2 (Fig. 5) and Cu/Commercial-SiO2 (Fig. S4) are calculated to be 70.8 m2 g−1 and 139.8 m2 g−1, respectively. As shown in Fig. 5, the nitrogen adsorption-desorption isotherms of the Cu@SiO2 nanospheres displace a type-IV curves with a small hysteresis loop occur at a relative pressure of 0.8–1.0, indicating the existence of mesopores in the samples, as evidenced by DFT pore diameter distribution (10 ~ 43 nm) in Fig. S5. These mesopores are likely due to the void spaces among the stacked Cu@SiO2 nanospheres. The DFT pore diameter distribution of Cu@SiO2 nanospheres in Fig. S5 also shows that there are micropores (1.1 nm) on the SiO2 shells of the Cu@SiO2 nanospheres. These pores can provide the reactants readily access the Cu NPs core and the products can easily exit through the pores.

Discussion

The catalytic activity on the hydrolysis of ammonia borane (AB) was tested for the as-synthesized samples. Figure 6 shows the time course of the hydrogen evolution from the aqueous AB using the different catalysts. It is observed that the hydrolysis reaction rate and amount of hydrogen significantly depend on the catalysts. No hydrogen generation is observed for silica, suggesting that silica has no catalytic activity for the hydrolysis of AB. The evolution of 3.0, 2.9, 3.0 and 2.1 mol of hydrogen is completed in 10.3, 37.0, 66.0 and 170.0 min, respectively, in the presence of the as-synthesized Cu@SiO2, Cu/Commercial SiO2, Cu/SiO2 and free Cu NPs at room temperature. The turnover frequency (TOF) values catalyzed by Cu@SiO2, Cu/Commercial SiO2, Cu/SiO2 and Cu NPs are around 3.24, 0.87, 0.50 and 0.14 mol H2 mol Cu−1 min−1, respectively. The catalytic activities are in the order of Cu@SiO2 > Cu/Commercial SiO2 > Cu/SiO2 > Cu NPs. CO temperature programmed desorption (CO-TPD) curves for Cu@SiO2 and Cu/Commercial SiO2 NPs shown in Fig. S6 reveal that the reactive surfaces of Cu are 9.46 and 1.31 m2 g−1, respectively, in line with the catalytic activity tests for the hydrolytic dehydrogenation of AB and HB (vide infra). To the best of our knowledge, the present Cu@SiO2 nanospheres exhibit the second highest activity among the Cu nanocatalysts ever reported for hydrolytic dehydrogenation of AB (See Table S1). Although the activity of Cu@SiO2 nanospheres is slightly lower than that of our previous reported catalysts Cu/RGO (3.61)37, the Cu@SiO2 nanospheres show a much better reusability than Cu/RGO (vide infra). The excellent catalytic performance of the Cu@SiO2 nanocatalysts can be attributed to the ultrafine and monodisperse Cu NPs within the porous silica shells, which can hinder Cu NPs cores from undergoing deformation or aggregation during the hydrolysis reaction.

In order to get the activation energy (Ea) of AB catalyzed by Cu@SiO2 core-shell nanospheres, the hydrolysis reactions at different temperatures were carried out. Figure 7a shows mol H2/mol AB vs. reaction time in the hydrolysis of AB (0.2 M, 5 mL) catalyzed by Cu@SiO2 nanospheres at various temperatures in the range of 298–316 K. The hydrogen generation rate increases by increasing the reaction temperature as expected. The values of reaction rate constant k at different temperatures are measured from the slope of the linear part of each plot in Fig. 7a. The Arrhenius plot of lnk versus 1/T for the catalyst is plotted in Fig. 7b. From the slop of the straight line, the activation energy for the hydrolysis of AB in the presence of Cu@SiO2 nanospheres is determined to be approximately 36 ± 1 kJ mol−1, being lower than most of the reported values, indicating the superior catalytic performance of the catalysts (Table 1)9,35,37,48,54,55,56,57,58,59.

The catalytic performance of Cu@SiO2, Cu/commercial SiO2, Cu/SiO2 and free Cu NPs were also investigated for the hydrolysis of HB. As shown in Fig. 8, the trends observed for the catalytic hydrolysis of HB by the different catalysts are similar as that for the hydrolysis reaction of AB. The evolution of 3.0, 2.9, 2.6 and 2.4 mol of hydrogen is finished in 4.4, 7.5, 9.2 and 47.5 min, respectively, in the presence of the as-synthesized Cu@SiO2, Cu/Commercial SiO2, Cu/SiO2 and free Cu NPs at room temperature. The Cu@SiO2 core-shell nanospheres show a superior activity as compared to Cu/commercial SiO2, Cu/SiO2 and free Cu NPs for the catalytic hydrolysis of HB. The TOF and activation energy of Cu@SiO2 core-shell nanospheres for the hydrolysis of HB are estimated to be 7.58 mol H2 mol Cu−1 min−1 and 51 ± 2 kJ/mol (Fig. S7), respectively.

Reusability of catalysts is very important for the practical application. In this sense, the recycle test of the Cu@SiO2 core-shell nanospheres for the hydrolysis of AB and HB were carried out. As shown in Fig. 9, the catalytic activity of Cu@SiO2 in the hydrolysis of AB and HB retain 90 and 85% of their initial activity with a complete release of hydrogen by hydrolysis reaction eqn.1 and 2 respectively, even at the tenth recycles, indicating that the Cu@SiO2 core-shell nanospheres have a good durability in the catalytic reactions. In contrast, the catalytic activity for the hydrolysis of AB and HB show a significant decrease in the presence of the commercial SiO2 supported Cu NPs after three runs (Fig. S8), probably because the Cu NPs supported on the surface of silica are easily aggregated and then resulting in lose the activity site in the recycling process. After cycle tests, ICP analysis revealed that the copper leaching from Cu@SiO2 and Cu/commercial SiO2 were 0.1 and 7.0% of total copper, respectively. The results reveal that the Cu@SiO2 core-shell nanosphere can effectively prevent the leaching of Cu metal, thus making Cu@SiO2 be an excellent catalyst with high catalytic activity and good reusability. This prominent feature can also be evidenced by TEM. Comparing with Fig. 2, the morphology and the size of the spherical silica nanospheres for Cu@SiO2 after the catalytic reaction (Fig. S9) shows no obvious changes before and after catalytic hydrolysis reaction. The size of the Cu NPs embedded in the SiO2 spheres almost kept unchanged after catalytic reaction. In addition, a high temperature, 573 K, was used for heat treatment to prepare Cu@SiO2-573 K. The Cu@SiO2-573 K with heat treatment still remain high activity, which release a stoichiometric amount of H2 from aqueous AB and HB (H2/(AB or HB) = 3) in 12.5 and 5.9 min, respectively (Fig. S10 & S11), indicating that the Cu@SiO2 nanospheres have good thermal stability.

In conclusion, for the first time, we have developed a facile one-pot synthetic route to synthesis of ultrafine copper NPs within porous silica nanospheres under ambient conditions. The TEM reveals that ultrafine Cu NPs of around 2 nm are effectively embedded in the center of porous silica nanospheres. The core-shell Cu@SiO2 NPs show a much better catalytic activity, in comparison to the commercial SiO2 supported Cu NPs, SiO2 supported nanospheres Cu NPs and free Cu NPs for hydrolytic dehydrogenation of AB and HB at room temperature. The TOF for Cu@SiO2 nanospheres in the hydrolytic dehydrogenation of AB and HB are measured to be 3.24 and 7.58 mol H2 mol Cu−1 min−1, respectively. Moreover, the complete release of hydrogen is achieved even in the tenth run and the Cu@SiO2 nanospheres preserve 90 and 85% of their initial catalytic activity for the hydrolytic dehydrogenation of AB and HB, respectively, indicating that the catalyst has a good reusability. The high performance and cost-effective catalyst may strongly encourage the practical application of AB and HB as promising hydrogen storage materials.

Methods

Materials

Ammonia borane (NH3BH3, AB, Aldrich, 90%), copper chloride dihydrate (CuCl2·2H2O, Sinopharm Chemical Reagent Co. Ltd., >99%), cyclohexane (C6H12, Tianjin Fuchen Chemical Reagent, >99.5%), polyethylene glycolmono-4-nonylphenyl ether n ≈ 5 (NP-5, TCI), tetraethoxysilane (TEOS, Aldrich, 98%), ammonia solution (NH3·H2O, Nanchang Chemical Works, 28%), methanol (CH3OH, Tianjin Fuchen Chemical Reagent, 99.5%), acetone ((CH3)2CO, Nanchang Chemical Works, >99.5%), commercial SiO2 (specific surface area = 200 m2 g−1), Degussa, 99.8%), sodium borohydride (NaBH4, Aldrich, 99%), hydrazine hemisulfate ((N2H4)2·H2SO4) and n-pentane were used without further purification. Ultrapure water with the specific resistance of 18.3 MΩ·cm was obtained by reversed osmosis followed by ion exchange and filtration.

Instrumentation

The microstructure of the samples were investigated using a transmission electron microscope (TEM, JEM-2010) equipped with an energy-dispersive X-ray detector (EDX). Scanning electron microscope (SEM) image was taken on a SU8020 cold field-emission instrument. Powder X-ray diffraction (XRD) studies were performed on a Rigaku RINT-2200 X-ray diffractometer with a Cu Kα source (40 kV, 20 mA). The weight content of copper in Cu@SiO2 nanospheres was analyzed by means of an inductively coupled plasma (ICP) spectrophotometer (Varian, 725-ES). X-ray photoelectron spectrometry (XPS) was performed with a Thermo ESCALAB 250 multifunctional imaging electron spectrometer by using an Al Kα source. Nitrogen adsorption-desorption isotherms were carried out on a Micromeritics ASAP 2050 system at 77 K. The specific surface area and pore size distribution were determined by the Brunauer-Emmett-Teller (BET) equation and density functional theory (DFT) method, respectively. Temperature programmed desorption (TPD) experiments were measured on a Micromeritics AutoChem II 2920 system and the active surface area (SCu) was obtained by CO chemisorption on the same instrument. The purity of the obtained HB was determined by Bruker 400 M liquid NMR using CD3CN as solvent.

Synthesis of ultrafine copper NPs within porous silica nanospheres (Cu@SiO2)

Ultrafine copper NPs within silica nanospheres (Cu@SiO2) were synthesized via a one-pot synthetic route in a reversed micelle system according to the literature procedure45,46,47,48,49. Briefly, calculated amount of aqueous solution of CuCl2·2H2O (2.16 mL, 0.12 M) were rapidly injected into 480 mL of NP-5 (20.16 g) cyclohexane solution. After stirring at room temperature for about 15 h, an aqueous ammonia solution (28 wt%, 2.16 mL) was injected rapidly and after 2 h, TEOS (2.49 mL) was added rapidly. The solution was stirred for 2 days at room temperature. The Cu(II)@SiO2 nanospheres were isolated by addition of methanol to destabilize the reversed-micelle system and centrifugation at 10000 rpm for 8 min. The product obtained was further washed with cyclohexane and acetone. After drying in vacuum oven at 313 K overnight, the Cu(II)@SiO2 nanospheres were further reduced by 5 mL of aqueous AB solution (AB: 0.2 M, Cu/AB = 0.09). The solids obtained were used as the as-synthesized Cu@SiO2 catalysts. The copper content of the product was analyzed by ICP and calculated to be 2.2 wt%. For thermal stability, the Cu(II)@SiO2 nanospheres were calcined at 573 K for 5 h in air, reduced by AB (0.2 M, 5 mL) and label as Cu@SiO2-573 K.

Synthesis of copper NPs supported on silica (Cu/Commercial SiO2 and Cu/SiO2)

The copper NPs supported on commercial silica (Cu/Commercial SiO2) and silica nanospheres (Cu/SiO2) in this study were prepared by the conventional impregnation and subsequent AB reduction (0.2 M, 5 mL). The Cu content was kept to be about 2.2 wt% and the molar ratio of Cu to AB was kept a constant of 0.09. Silica nanospheres, which were prepared using a similar method as for the Cu/@SiO2 nanospheres without copper precursor, were used as the support for preparing silica nanospheres supported copper NPs.

Synthesis of free copper NPs without silica (Cu NPs)

The copper NPs without silica were prepared in situ synthesis method. 15.5 mg CuCl2·2H2O was dissolved in 5 mL of distilled water and 34.3 mg of AB (Cu/AB = 0.09) was added into the solution with shaking.

Synthesis of hydrazine borane (N2H4BH3, HB)

Hydrazine borane was synthesized by the method reported in literature60. The detailed experimental process could be found in the Supplementary material.

Hydrolytic dehydrogenation of AB and HB

Typically, ammonia borane (NH3BH3, AB, 1 mmol) or hydrazine borane (N2H4BH3, HB, 1 mmol) and catalysts was placed in a two-necked round-bottomed flask. One neck of the flask was connected to a gas burette to measure the volume of hydrogen. The reaction started when 5 mL distilled water was injected into the mixture using a syringe and the evolution of gas was monitored using the gas burette. The reaction was completed when there was no more gas generation.

Recycle test of Cu@SiO2 for hydrolytic dehydrogenation of AB and HB

After the first run of hydrogen generation reaction was completed, the catalyst was separated from the reaction solution by centrifugation and washed with water for several times. The washed catalyst was then re-dispersed in 5 mL of water in a flask and another equivalent of AB or HB (1 mmol) was subsequently added to the reaction system and the released gas was monitored by the gas burette. The reactions were repeated 10 times under ambient atmosphere at room temperature. After cycle tests, the catalysts were separated from the reaction solution by centrifugation, washed with water for several times and dried in vacuum oven at 313 K overnight.

References

Schlapbach, L. & Zuttel, A. Hydrogen-storage materials for mobile applications. Nature 414, 353–358 (2001).

Chen, P., Xiong, Z., Luo, J., Lin, J. & Tan, K. L. Interaction of hydrogen with metal nitrides and imides. Nature 420, 302–304 (2002).

Hamilton, C. W., Baker, R. T., Staubitz, A. & Manners, I. B-N compounds for chemical hydrogen storage. Chem. Soc. Rev. 38, 279–293 (2009).

Yadav, M. & Xu, Q. Liquid-phase chemical hydrogen storage materials. Energy Environ. Sci. 5, 9698–9725 (2012).

Demirci, U. B. & Miele, P. Chemical hydrogen storage: ‘material’ gravimetric capacity versus ‘system’ gravimetric capacity. Energy Environ. Sci. 4, 3334–3341 (2011).

Lu, Z. H. & Xu, Q. Recent Progress in boron- and nitrogen-based chemical hydrogen storage. Funct. Mater. Lett. 5, 1230001 (2012).

Yao, Q. L., Chen, X. S. & Lu, Z. H. Catalytic dehydrogenation of NH3BH3, N2H4 and N2H4BH3 for chemical hydrogen storage. Energy Environ. Focus 3, 236–245 (2014).

Xu, Q. & Chandra, M. A Portable hydrogen generation system: catalytic hydrolysis of ammonia-borane. J. Alloys Compd. 446–447, 729–732 (2007).

Lu, Z. H. et al. Catalytic hydrolysis of ammonia borane via magnetically recyclable copper iron nanoparticles for chemical hydrogen storage. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 38, 5330–5337 (2013).

Lu, Z. H. et al. Synergistic catalysis of MCM-41 immobilized Cu-Ni nanoparticles in hydrolytic dehydrogeneration of ammonia borane. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 39, 13389–13395 (2014).

Jiang, H. L. & Xu, Q. Catalytic hydrolysis of ammonia borane for chemical hydrogen storage. Catal. Today 170, 56–63 (2011).

Karahan, S., Zahmakıran, M. & Özkar, S. Catalytic hydrolysis of hydrazine borane for chemical hydrogen storage: highly efficient and fast hydrogen generation system at room temperature. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 36, 4958–4966 (2011).

Çelik, D., Karahan, S., Zahmakıran, M. & Özkar, S. Hydrogen generation from the hydrolysis of hydrazine-borane catalyzed by rhodium(0) nanoparticles supported on hydroxyapatite. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 37, 5143–5151 (2012).

Hannauer, J., Demirci, U. B., Geantet, C., Herrmann, J. M. & Miele, P. Transition metal-catalyzed dehydrogenation of hydrazine borane N2H4BH3 via the hydrolysis of BH3 and the decomposition of N2H4 . Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 37, 10758–10767 (2012).

Cao, C. Y., Chen, C. Q., Li, W., Song, W. G. & Cai, W. Nanoporous nickel spheres as highly active catalyst for hydrogen generation from ammonia borane. ChemSusChem 3, 1241–1244 (2010).

Ramachandran, P. V. & Gagare, P. D. Preparation of ammonia borane in high yield and purity, methanolysis and regeneration. Inorg. Chem. 46, 7810–7817 (2007).

Sun, D. H., Mazumder, V., Metin, Ö. & Sun, S. H. Methanolysis of ammonia borane by CoPd nanoparticles. ACS Catal. 2, 1290–1295 (2012).

Karahan, S., Zahmakıran, M. & Özkar, S. Catalytic methanolysis of hydrazine borane: a new and efficient hydrogen generation system under mild conditions. Dalton trans. 41, 4912–4918 (2012).

Li, Z., Zhu, G., Lu, G., Qiu, S. & Yao, X. Ammonia borane confined by a metal-organic framework for chemical hydrogen storage: enhancing kinetics and eliminating ammonia. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 132, 1490–1491 (2010).

Moury, R. et al. Hydrazine borane: synthesis, characterization and application prospects in chemical hydrogen storage. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 14, 1768–1777 (2012).

Hannauer, J. et al. High-extent dehydrogenation of hydrazine borane N2H4BH3 by hydrolysis of BH3 and decomposition of N2H4 . Energy Environ. Sci. 4, 3355–3358 (2011).

Çakanyıldırım, Ç., Demirci, U. B., Şener, T., Xu, Q. & Miele, P. Nickel-based bimetallic nanocatalysts in high-extent dehydrogenation of hydrazine borane. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 37, 9722–9729 (2012).

Zhong, D. C., Aranishi, K., Singh, A. K., Demirci, U. B. & Xu, Q. The synergistic effect of Rh-Ni catalysts on the highly-efficient dehydrogenation of aqueous hydrazine borane for chemical hydrogen storage. Chem. Commun. 48, 11945–11947 (2012).

Li, C. et al. Synthesis of supported Ni@(RhNi-alloy) nanocomposites as an efficient catalyst towards hydrogen generation from N2H4BH3 . Chem. Commun. 49, 9992–9924 (2013).

Clémençon, D., Petit, J. F., Demirci, U. B., Xu, Q. & Miele, P. Nickel- and platinum-containing core@shell catalysts for hydrogen generation of aqueous hydrazine borane. J. Power Sources 260, 77–81 (2014).

Yang, L., Luo, W. & Cheng, G. Z. Graphene-supported Ag-based core-Shell nanoparticles for hydrogen generation in hydrolysis of ammonia borane and methylamine borane. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 5, 8231–8240 (2013).

Zahmakıran, M. & Özkar, S. Zeolite framework stabilized rhodium(0) nanoclusters catalyst for the hydrolysis of ammonia-borane in air: outstanding catalytic activity, reusability and lifetime. Appl. Catal. B-Environ. 89, 104–110 (2009).

Xi, P. et al. Surfactant free RGO/Pd nanocomposites as highly active heterogeneous catalysts for the hydrolytic dehydrogenation of ammonia borane for chemical hydrogen storage. Nanoscale 4, 5597–5601 (2012).

Wang, X., Liu, D., Song, S. & Zhang, H. Synthesis of highly active Pt-CeO2 hybrids with tunable secondary nanostructures for the catalytic hydrolysis of ammonia borane. Chem. Commun. 48, 10207–10209 (2012).

Yan, J. M., Zhang, X. B., Han, S., Shioyama, H. & Xu, Q. Iron-nanoparticle-catalyzed hydrolytic dehydrogenation of ammonia borane for chemical hydrogen storage. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 47, 2287–2289 (2008).

Luo, Y. C., Liu, Y. S., Huang, Y., Liu, X. Y. & Mou, C. Y. Mesoporous silica supported cobalt catalysts for hydrogen generation in hydrolysis of ammonia borane. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 37, 7280–7290 (2013).

Li, P. Z., Aijaz, A. & Zhou, Q. Highly dispersed surfactant-free nickel nanoparticles and their remarkable catalytic activity in hydrolysis of ammonia borane for hydrogen generation. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 51, 1–5 (2012).

Li, Y. Q., Xie, L., Li, Y., Zheng, J. & Li, X. G. Metal-organic-framework-based catalyst for highly efficient H2 generation from aqueous NH3BH3 solution. Chem. Eur. J. 15, 8951–8954 (2009).

Kalidindi, S. B., Sanyal, U. & Jagirdar, B. R. Nanostructured Cu and Cu@Cu2O core shell catalysts for hydrogen generation from ammonia-borane. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 10, 5870–5874 (2008).

Zahmakıran, M., Durap, F. & Özkar, S. Zeolite confined copper(0) nanoclusters as cost-effective and reusable catalyst in hydrogen generation from the hydrolysis of ammonia-borane. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 35, 187–197 (2010).

Kaya, M., Zahmakıran, M., Özkar, S. & Volkan, M. Copper(0) nanoparticles supported on silica-coated cobalt ferrite magnetic particles: cost effective catalyst in the hydrolysis of ammonia-borane with an exceptional reusability performance. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 4, 3866–3873 (2012).

Yang, Y. W. et al. Facile in situ synthesis of copper nanoparticles supported on reduced graphene oxide for hydrolytic dehydrogenation of ammonia borane. Rsc Advance 4, 13749–13752 (2014).

Yamada, Y., Yano, K. & Fukuzumi, S. Catalytic application of shape-controlled Cu2O particles protected by Co3O4 nanoparticles for hydrogen evolution from ammonia borane. Energy Environ. Sci. 5, 5356–5363 (2012).

Li, C. M. et al. Binary Cu-Co catalysts derived from hydrotalcites with excellent activity and recyclability towards NH3BH3 dehydrogenation. J. Mater. Chem. A 1, 5370–5376 (2013).

Kalidindi, S. B., Indirani, M. & Jagirdar, B. R. First row transition metal ion-assisted ammonia-borane hydrolysis for hydrogen generation. Inorg. Chem. 47, 7424–7429 (2008).

Yao, Q. L. et al. Methanolysis of ammonia borane by shape-controlled mesoporous copper nanostructures for hydrogen generation. Dalton. Trans. 10.1039/c4dt02873b (2015).

Gu, X. J., Lu, Z. H., Jiang, H. L., Akita, T. & Xu, Q. Synergistic catalysis of metal-organic framework-immobilized Au-Pd nanoparticles in dehydrogenation of formic acid for chemical hydrogen storage. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 133, 11822–11825 (2011).

Yang, T., Liu, J., Zheng, Y., Monteiro, M. J. & Qiao, S. Facile fabrication of core–shell-structured Ag@carbon and mesoporous yolk–shell-structured Ag@carbon@silica by an extended stober method. Chem. Eur. J. 19, 6942–6945 (2013).

Liu, H., Cao, C., Li, P., Yu, Y. & Song, W. Core-shell structured nanospheres with mesoporous silica shell and Ni core as a stable catalyst for hydrolytic dehydrogenation of ammonia borane. J. Energy Chem. 23, 50–56 (2014).

Umegaki, T. et al. Co-SiO2 nanosphere-catalyzed hydrolytic dehydrogenation of ammonia borane for chemical hydrogen storage. J. Power Sources 195, 8209–8214 (2010).

Jiang, H. L. et al. Bimetallic Au-Ni nanoparticles embedded in SiO2 nanospheres: synergetic catalysis in hydrolytic dehydrogenation of ammonia borane. Chem. Eur. J. 16, 3132–3137 (2010).

Lu, Z. H., Jiang, H. L., Yadav, M., Aranishi, K. & Xu, Q. Synergistic batalysis of Au-Co@SiO2 nanospheres in hydrolytic dehydrogenation of ammonia borane for chemical hydrogen storage. J. Mater. Chem. 22, 5065–5071 (2012).

Yao, Q. L. et al. Ultrafine Ru nanoparticles embedded in SiO2 nanospheres: highly efficient catalysts for hydrolytic dehydrogenation of ammonia borane. J. Power Sources 257, 293–299 (2014).

Miyao, T., Minoshima, K. & Naito, S. Remarkable hydrogen occlusion ability of hollow Ir-SiO2 nanoparticles prepared by reversed micelle techniques. J. Mater. Chem. 15, 2268–2270 (2005).

Liu, J. et al. Yolk/shell nanoparticles: new platforms for nanoreactors, drug delivery and lithium-ion batteries. Chem. Comm. 47, 12578–12591 (2011).

Giersig, M., Ung, T., Liz-Marzan, L. M. & Mulvaney, P. Direct observation of chemical reactions in silica-coated gold and silver nanoparticles. Adv. Mater. 9, 570–575 (1997).

Haeiwa, T., Segawa, K. & Konishi, K. Magnetic properties of isolated Co nanoparticles in SiO2 capsule prepared with reversed micelle. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 310, E809–E811 (2007).

Guerrero-Martinez, A., Perez-Juste, J. & Liz-Marzan, L. M. Recent progress on silica coating of nanoparticles and related nanomaterials. Adv. Mater. 22, 1182–1195 (2010).

Chen, G., Desinan, S., Rosei, R., Rosei, F. & Ma, D. Synthesis of Ni-Ru alloy nanoparticles and their high catalytic activity in dehydrogenation of ammonia borane. Chem. Eur. J. 18, 7925–7930 (2012).

Xu, Q. & Chandra, M. Catalytic activities of non-noble metals for hydrogen generation from aqueous ammonia-borane at room temperature. J. Power Sources 163, 364–370 (2006).

Du, Y. S., Cao, N., Yang, L., Luo, W. & Cheng, G. Z. One-step synthesis of magnetically recyclable RGO supported Cu@Co core-shell nanoparticles: highly Efficient Catalysts for Hydrolytic Dehydrogenation of Ammonia Borane and methylamine borane. New J. Chem. 37, 3035–3042 (2013).

Ozay, O., Inger, E., Aktas, N. & Sahiner, N. Hydrogen production from ammonia borane via hydrogel template synthesized Cu, Ni, Co composites. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 36, 8209–8216 (2011).

Qiu, F. et al. Synthesis of Cu@FeCo core-shell nanoparticles for the catalytic hydrolysis of ammonia borane. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 39, 436–441 (2014).

Chandra, M. & Xu, Q. Room temperature hydrogen generation from aqueous ammonia-borane using noble metal nano-clusters as highly active catalysts. J. Power Sources 168, 135–142 (2007).

Gunderloy, F. C. Hydrazine-Mono- and Bisborane. Inorg. Synth. 9, 13–16 (1967).

Acknowledgements

This work is supported in part by National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 21103074 and 21463012), Natural Science Foundation of Jiangxi Province of China (No. 20114BAB203010 and 20132BAB203014) and Jiangxi Provincial Education Department (No. GJJ14230).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

L.Z.H. and Y.Q.L. designed the experiments, ananlyzed the data and wrote the paper; Y.Q.L. and Z.Z.J. performed experiments; C.X.S. and L.Y.Q. contributed to the discussion; L.Z.H. supervised the project; All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder in order to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Yao, Q., Lu, ZH., Zhang, Z. et al. One-pot synthesis of core-shell Cu@SiO2 nanospheres and their catalysis for hydrolytic dehydrogenation of ammonia borane and hydrazine borane. Sci Rep 4, 7597 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep07597

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/srep07597

This article is cited by

-

Effect of Cu@polythiophene yolk–shell nanofiller on the electrical, mechanical and thermal properties of poly(vinyl alcohol) thin films

Polymer Bulletin (2023)

-

Synthesis, characterization, and the study of structural and optical properties of core/shell nanoparticles of SiO2@CuO for solar absorption collectors application

Journal of Materials Science: Materials in Electronics (2022)

-

Simple synthesis of gold-decorated silica nanoparticles by in situ precipitation method with new plasmonic properties

SN Applied Sciences (2021)

-

Recovery of Pd as PdO from Pd/SiO2 catalyst by leaching using hydrochloric acid

Journal of Material Cycles and Waste Management (2021)

-

Development of novel and green NiFe2O4/geopolymer nanocatalyst based on bentonite for synthesis of imidazole heterocycles by ultrasonic irradiations

Scientific Reports (2020)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.