Abstract

We report pronounced enhancement of photoelectrochemical hydrogen generation of a quantum dot-sensitized hybrid-TiO2 (QD/H-TiO2) electrode that is composed of a mesoporous TiO2 layer sandwiched by a double sided energy harvesting layer consisting of a surface-textured TiO2 inverse opals layer on the bottom and a patterned mesoporous TiO2 layer on the top. CdSe/H-TiO2 exhibits a maximum photocurrent density of ~16.2 mA/cm2, which is 35% higher than that of the optimized control sample (CdSe/P25), achieved by matching of the bandgap of quantum dot-sensitization with the wavelength where light harvesting of H-TiO2 is observed. Furthermore, CdSe/H-TiO2 under filtered exposure conditions recorded current density of ~14.2 mA/cm2, the greatest value in the visible range. The excellent performance of the quantum dot-sensitized H-TiO2 suggests that alteration of the photoelectrodes to suitable nanostructures with excellent light absorption may offer optimal strategies for attaining maximum efficiency in a variety of photoconversion systems.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Photoelectrochemical (PEC) cells are useful devices designed for the chemical process of generating hydrogen via electrolysis of water, namely water splitting, under irradiation of a broad spectrum of sunlight1,2,3,4. In general, PEC devices are composed of photoelectrodes, where oxidation/reduction of water occurs with response to sunlight and appropriate aqueous electrolytes containing a redox couple5,6,7. TiO2 has proven to be a promising photoelectrode in photoconversion systems due to its flat band potential, fast electron transfer mechanism and photoelectrochemical stability in most aqueous solutions8,9,10. However, the use of TiO2 as a single electrode material is fundamentally hampered by its large bandgap (3.2 eV), thus resulting in truncated and inclusively low efficiency in the visible region, which accounts for almost half of the entire sunlight spectrum. Accordingly, extending the light absorption window of the photoelectrode to visible light is considered critical to increase the efficiency of photoconversion11,12,13. Notable efforts to lower the bandgap of TiO2 include doping of heteroatoms14,15,16 or coating of metal or semiconductor particles utilizing excitation of surface plasmons17,18,19 or quantum dot-sensitization5,20,21, permitting excitation of electrons in the photoelectrodes at energies much below TiO2's original energy bandgap22,23,24. Among these approaches, quantum dot-sensitization has drawn considerable attention since it has shown an enhanced interfacial charge transfer mechanism via multiple excitations by single photon absorption.

Light harvesting refers to enhancement of absorbed light via either photon trapping25,26,27 or anti-reflection (AR)28,29,30, leading to an increase in the fraction of available light31,32. It has been reported that nanostructures can exhibit excellent absorption properties in the visible region via light harvesting, when their dimensions are comparable to the wavelength of light33. By enhancing absorption in the visible range via light harvesting, it becomes possible to more effectively sensitize quantum dots with a bandgap in the range of visible light, leading to maximal power conversion efficiency of quantum dot-based PEC cells.

Mesoporous TiO2 nanostructures fabricated by P25 with a mean diameter of about 25 nm have been widely used for fabrication of the working electrode in dye-sensitized solar systems, a representative photoconversion system, due to their advantage of large surface area for adsorption of dye molecules. However, the small particles are not able to efficiently harvest light in the red and near-infrared regions of the light spectrum and they also reflect a large amount of light due to the high refractive index of TiO2. Proper modification of the P25 photoelectrode is thus needed and careful design of quantum dot-sensitized devices based on a light harvesting mechanism is crucial to maximize the efficiency in photoconversion systems.

Here, we report an optimized quantum dot-sensitized hybrid-TiO2 (QD/H-TiO2) electrode sandwiched with light harvesting layers. The H-TiO2 electrode is constructed using a 4.5 μm-thick mesoporous TiO2 film made of crystalline nanoparticles (25 nm) and additionally a 500 nm-thick patterned mesoporous TiO2 layer on the top and 1 μm-thick surface-textured TIO (st-TIO) layer on the bottom, both with diameters on the order of hundreds of nanometers, with the capability of AR and photon trapping, respectively, contributing to maximized light harvesting. The configuration of the light harvesting layer sitting on both the bottom and top of the mesoporous TiO2 layer provides devices with similar mechanism to mirrors in a laser, where entrapped light is enhanced by repeated reflection at both ends and thus maximizes the intensity of the absorbed light at a wider solar spectrum. Furthermore, CdSe/H-TiO2 greatly broadens the range of photoconversion below the band gap of H-TiO2 by enhanced quantum dot-sensitized electron transport substantially supported by the light harvesting mechanism of H-TiO2. Under AM 1.5 G simulated sunlight illumination, the maximum photocurrent density of CdSe/H-TiO2 reaches ~16.2 mA/cm2, which is 35% higher than that of the optimized control sample (CdSe/P25), at an applied bias of 0.5 V versus Ag/AgCl. More surprisingly, the photocurrent from hydrogen generation of CdSe/H-TiO2 solely by the visible spectrum reaches ~14.2 mA/cm2, which is the highest record value in the visible range and almost 88% of that obtained under UV-visible irradiation. The greatly improved performance of CdSe/H-TiO2, which is attributable to the ability of light harvesting of H-TiO2, suggests the strong need for engineering light in photoconversion systems.

Results

H-TiO2 was fabricated by the following four steps, as shown in Figure 1a. First, surface-activated polystyrene beads (PS) obtained by treatment with Triton X-100 were self-assembled using Colvin's method34 into a few layers of a hexagonal structure on a FTO substrate with a thickness of 1 μm.

Schematic illustrations and electron microscopy images of TiO2 structures.

(a) Schematic illustration of the fabrication process for the hybrid TiO2 structure (H-TiO2). (b) Top view SEM image of st-TIO for photon trapping. The inset shows transmittance electron microscopy (TEM) image of the mesoporous surface textured-TIO (st-TIO). (c) Top view SEM image of the patterned mesoporous TiO2 layer for anti-reflection. The inset shows the close-up image of the P25 particles. (d) Cross-sectional SEM image of H-TiO2. (e) Schematic illustration of pathway of incoming light engineered by H-TiO2 compared with the case of P25.

PS structures were infiltrated with a TiCl4 aqueous solution and annealed in an air condition, inducing gelation of a TiO2 sol and calcination of PS simultaneously and thus forming the TIO structure (I). Second, a surface textured titanium inverse opal (st-TIO, II) coated with a diameter of 7 nm TiO2 mesoporous structures was created by selective removal of triblock copolymer domains from the coated layer containing TiO2 precursors and block copolymers on TIO. In principle, the st-TIO has been designed to minimize the loss of surface area for reaction sites while achieving a photon trapping effect. Third, P25 mesoporous structures (III) were deposited onto the st-TIO with a thickness of 5 μm. Fourth, a top-patterned mesoporous P25 nanostructure (p-P25, IV) was created by imprinting using a 500 nm-thick PDMS mold with 500 nm diameter and 600 nm pitch square patterns followed by the sintering process. The targeted structure is H-TiO2, composed of a 4.5 μm-thick mesoporous TiO2 layer with a double sided energy harvesting layer comprising a 1 μm-thick st-TIO layer of a few hundred nanometer scale on the bottom and a 500 nm thick mesoporous TiO2 square pattern on the top, giving a total thickness of 6 μm. Figure 1b is a scanning electron microscopy (SEM) image of the st-TIO structure (II) with air holes with a diameter of 290 nm. The dimension of the TIO was determined so as to efficiently scatter light for maximized light trapping as optimized in our previous reports29,33,35. Figure 1c is a SEM image of patterned mesoporous TiO2 structures obtained by stamping a P25 layer using the PDMS molds followed by final sintering. The dimensions were fixed for the maximized AR effects, based on the previous reports28,29. The volume fraction of TiO2 in the AR layer is found to be 0.46 based on SEM imaging and the effective refractive index of the AR layer is 1.62 as calculated in the Supporting Information. Figure 1d is a cross-sectional image of the H-TiO2 photoanode (V) sandwiched by a thin upper-layer of AR and a photon trapping under-layer. The surface area of the 6 μm-thick H-TiO2 obtained by BET was 119 m2/g, which is comparable to that of a compact mesoporous TiO2-nanocrystalline film (117 m2/g), as shown in Figure S1. Figure 1e illustrates the engineering mechanism of absorbed light to maximize the intensity of the light. When compared to a conventional P25 electrode, wherein a large portion of light is not only reflected but also limited to having a single pass through the device, H-TiO2 offers a much improved mechanism for light harvesting. Here, the double sided-large dimension structures function as a mirror at both ends: maximally absorbed photons by the help of the AR layer on the top are scattered further by the st-TIO frame on the bottom, permitting effective light harvesting via multi-passes of entrapped photons through the entire device.

The enhanced AR property and photon trapping effects due to coupling of properly designed double-sided light harvesting layers can be quantified by the (specular angle) reflection spectra and diffuse reflection spectra, respectively. The reflection spectra were obtained by shining light from a 5 μm-thick pure P25 and 5 μm top-surface patterned mesoporous P25 (p-P25) composed of 4.5 μm-thick P25 and an upper layer of patterns with a diameter of 500 nm and 500 nm thickness. P25 was chosen as a control sample since it has been shown to have excellent features as a working electrode in photovoltaic devices. In this configuration, the light passes through air/(TiO2 patterns)/nanocrystalline TiO2 interfaces from air to the TiO2 nanocrystalline layer and it is assumed that the majority of reflectance originates from the interface of air (n = 1) and TiO2 (n = 2.49) due to the notable difference of the refractive index. Figure 2a shows that p-P25 gives ~20% lower reflectance as compared to the pure TiO2 structure over the entire spectral range. This implies that much more light is able to participate in the photoconversion process in p-P25. This is attributable to the gradual change in the refractive index between the air and TiO2 nanocrystalline layers in p-P25 (1/1.63/2.49, nAR = 1.63 as calculated in the Supporting Information), since the porosity of the patterned TiO2 layer can modulate the effective refractive index of the diffraction grating layer29,36,37. In order to investigate the intensity of scattered light under beam irradiation on the device, the diffuse reflectance spectra of 6 μm-thick TiO2 films made in the form of P25, P25/st-TIO and H-TiO2 were measured as shown in Figure 2b. A schematic illustration of the samples is shown in Figure 2e. Interestingly, compared to the pristine P25 film, both films with a 1 μm-thick st-TIO layer (P25/st-TIO and H-TiO2) showed significantly higher diffuse reflection spectra in the visible spectrum of light (380–800 nm), indicating that the absorbed light was efficiently scattered within the nanostructure film. The effect of introduction of the light harvesting layers into the P25 film was further exploited by the transmittance spectra by shining light from top to bottom (Figure 2c). As expected from the low absorption coefficient of P25 in the visible region, a significant fraction of the light passes through 6 μm-thick P25 at the longer wavelength range, which clearly shows light harvesting did not occur (black curve). However, when a 1 μm-thick st-TIO layer was introduced into 5 μm-thick P25 on the bottom, creating 6 μm-thick hybrid samples (blue and red curves), the transmission of light is greatly reduced, indicating that most of the light is re-absorbed by the structure in the devices. This is ascribed to the introduction of a few hundred nanometer scale structure as the photon trapping layer. Finally, UV-visible spectroscopic measurements were undertaken in order to explore the ultimate optical response of nanostructured TiO2 with and without light harvesting layers. Figure 2d shows the UV-visible absorption spectra of an all 6 μm-thick plain P25, p-P25, P25/st-TIO and H-TiO2 illuminated at normal incidence from the air side. The absorption peaks spanning from 350 to 400 nm were assigned to the absorption of the conventional TiO2 nanoparticles. An intense and wider spectrum with a broad absorption band ranging from 400 to 800 nm compared to pure P25 is achieved when either a top or bottom light harvesting layer is adopted. Notably, st-TIO contributed more to increment of the absorption band than anti-reflective p-P25 layer, implying the greater influence of photon trapping effects than AR effects on light harvesting. Conclusively, when the double sided layer is applied, greatly enhanced UV spectra in the visible range are observed, even though the density of TiO2 particles is lower than that of P25. The enhanced UV absorption of H-TiO2 is attributed to the synergetic combination of AR and photon trapping effects obtained by the larger dimension nanostructures, which allow for longer effective light path lengths and thus create a clear and strong absorption band in the longer wavelength region ranging from 400 nm to 800 nm.

Optical properties of P25, p-P25, P25/st-TIO and H-TiO2 (p-P25/st-TIO).

(a) Reflectance spectra recorded, within the UV-visible light wavelength range, on the pure P25 and top-surface patterned P25 (p-P25). (b) Diffuse reflectance spectra of P25, P25/st-TIO and H-TiO2, (c) Transmittance spectra, (d) UV-visible absorption spectra and (e) Schematic illustration of P25, p-P25, P25/st-TIO and H-TiO2.

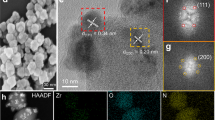

In order to further enhance the working capability of H-TiO2 in the visible wavelength region, CdSe quantum dots (QDs) were deposited onto the H-TiO2 structure. The deposition of CdSe on TiO2 was carried out via 20 cycles of successive ionic layer adsorption and reaction (SILAR) method. Figure 3a presents TEM images of the CdSe QDs deposited onto H-TiO2. Slightly randomly deposited spherical QDs with an average particle size of 4.5 nm with lattice spacings of 0.35 and 0.20 nm, which are consistent with the known values for the (002) and (103) planes of CdSe are observed. The enhanced optical properties due to the introduction of QDs on the hybrid samples are compared with the properties observed for CdSe/P25 and pure H-TiO2 in Figure 3b. An apparent increase and broadening in the optical density near the band gap of CdSe covering a range of 400–800 nm confirms the creation of CdSe nanoparticles and the ability of QD-sensitization. It should be noted that the overlap of the excitation wavelength of QDs and the regions of the wavelength with great absorption of H-TiO2 is crucial to maximize the efficient sensitization of QDs. CdSe/P25 also presents enhanced absorption after the deposition of CdSe, yet with a much lower absorption coefficient than that of CdSe/H-TiO2, likely due to low absorption of pristine P25 in the visible region where CdSe is excited. Figure 3c presents photoluminescence (PL) spectra of the CdSe QDs and CdSe/H-TiO2. Compared to the PL spectrum of CdSe, which shows a typical near-band-edge emission at 630 nm, that of CdSe/H-TiO2 is remarkably quenched. This clearly indicates a facile electron transfer mechanism at the interface between CdSe and TiO2 nanoparticles and thus low likelihood of electron-hole recombination within CdSe.

Discussion

In order to investigate the hydrogen generating efficiency of the samples, photo-electrochemical measurements were carried out on a P25 control sample, p-P25, P25/st-TIO, H-TiO2 and CdSe/H-TiO2 using Ag/AgCl, a Pt mesh and as-prepared samples as a reference electrode, counter electrode and working electrode, respectively, in a 0.24 M Na2S and 0.35 M Na2SO3 electrolyte solution. This solution is commonly used as an electrolyte for quantum dot-based PEC systems, serving as the sacrificial agent. As shown in Figure 4a, which illustrates the electron transfer mechanism of CdSe/H-TiO2, after the excited electrons are transferred from quantum dots to the conduction band of TiO2, the electrons are withdrawn to the counter electrode where the hydrogen generation reaction occurs (An image capturing a large amount of H2 gas generation is presented in Figure S6 along with a movie clip)38,39. Meanwhile, the holes diffused to the surface of TiO2 or CdSe oxidize S2−. Figure 4b presents linear sweep voltammograms of the pristine P25, p-P25, P25/st-TIO and H-TiO2, which is described by the direct photoexcitation of electrons from the valence band of TiO2, under AM 1.5 G simulated sunlight illumination (100 mW/cm2). All samples with a light harvesting layer show higher photocurrent density than the P25 control sample. Surprisingly, the photocurrent density of an optimized H-TiO2 reaches ~1.65 mA/cm2 at an applied bias of 0.5 V40, which is approximately 2.5 times greater than that of the P25 control sample. This is the highest reported value of current density achieved using a single TiO2 electrode material, implying that our approach to maximize light harvesting via engineering structural control is successful and also suggesting massive potential of pristine H-TiO2 in photoconversion systems. Figure 4c compares linear sweep voltammograms of CdSe/H-TiO2 and CdSe/P25. When the system is further supported by QD sensitization, the photocurrent density of CdSe/H-TiO2 reaches ~16.2 mA/cm2, 35% higher than that obtained with CdSe/P25, under illumination of 100 mW/cm2. More surprisingly, as shown in Figure 4c, the photocurrent density of CdSe/H-TiO2 created by only visible light illumination (blue curve, AM 1.5, a cutoff filter (>420 nm)) reaches ~14.2 mA/cm2, ~88% of that of UV-visible irradiation (red curve) and comparable to the values under UV-visible irradiation in other detailed studies41,42,43, clearly indicating solely visible working capability of CdSe/H-TiO2. This surprising result is ascribed to the large enhancement of absorption of H-TiO2 in the visible range, which matches well with the excitation wavelength of CdSe, via efficient light harvesting. Figure 4d shows the photoresponse over time (J-t curve) of CdSe/H-TiO2 measured at 0.5 V with chopped illumination of AM 1.5 at a rate of 10 s exposure followed by 10 s non-illumination for UV-visible and visible light. The sharp spike in the photocurrent for both cases during the on/off illumination cycles indicates fast transport of photogenerated electrons from QDs to the current collector via the interior TiO2 networks in accordance with the result of the PL study (Figure 3c). The greater values in the photocurrent density of CdSe/H-TiO2 than in that of CdSe/P25 can be confirmed by a lower internal resistance measured by the electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS). The measurement was conducted at a frequency range from 100 kHz to 0.1 Hz under open circuit voltage conditions, which gives Nyquist plots composed of two semicircles. A small (first) semicircle at a high frequency represents the charge transfer resistance at the interfaces of the electrolyte/counter electrode whereas a large (second) semicircle at an intermediate frequency conveys the transport resistance of electrons at the TiO2/QD/electrolyte interface44. The smaller diameter of the second semicircle in CdSe/H-TiO2 indicates a lower interfacial charge transfer resistance between the TiO2 electrode and electrolytes and thus a more effective separation of photo-generated electron-hole pairs (a faster interfacial charge transfer to the electron donor/acceptor). The incident photon-to-electron conversion efficiency (IPCE) of CdSe/H-TiO2 exhibits overall higher values than that of CdSe/P25 with a maximum IPCE value of 70.1% (43.7% for CdSe/P25) at 575 nm, as shown in Figure 4e. Importantly, much stronger and broader responses of CdSe/H-TiO2 were achieved than those of CdSe/P25 from 400 to 630 nm, clearly indicating that CdSe/H-TiO2 offers superior quantum efficiency in water splitting in the visible region via light harvesting.

Schematic diagram and photocurrent response of P25 control, CdSe/P25, H-TiO2 and CdSe/H-TiO2 under AM 1.5 illumination (100 mW/cm2).

(a) Schematic diagram showing the hydrogen generating mechanism of CdSe/H-TiO2. (b) Linear sweep voltammetry measurements of P25, p-P25, P25/st-TIO and H-TiO2 under UV-visible and dark conditions. (c) Linear sweep voltammetry measurements of CdSe/P25 and CdSe/H-TiO2 under UV-visible, visible light illumination and dark conditions. (d) J-t curves of CdSe/H-TiO2 at a bias of 0.5 V under UV-visible and visible light illumination. (e) EIS response of P25 and H-TiO2. The measurement was conducted at a frequency range from 100 kHz to 0.1 Hz under open circuit voltage conditions. (f) Measurement of the incident photon-to-electron conversion efficiency. All experiments were performed with a 0.24 M Na2S and 0.35 M Na2SO3 electrolyte (pH = 12) and 100 mW/cm2 xenon lamp coupled with a UV/IR filter as the light source.

In conclusion, we report a finely designed H-TiO2 structure that maximizes light harvesting triggered by the configuration of a double sided layer with a few hundred nanometer scale while retaining the sufficient surface area. The observed optical properties confirm excellent light harvesting effects in the H-TiO2 structure, which can facilitate the water splitting reaction of a TiO2 semiconductor in the UV-visible range. The photocurrent of CdSe/H-TiO2 (~16.2 mA/cm2) was 35% greater than that of the representative CdSe/P25 photoelectrode, which is clearly recognized for outstanding performance. Importantly, CdSe/H-TiO2 under filtered exposure (λ > 420 nm) conditions recorded current density of ~14.2 mA/cm2, the highest value in the visible range, which is attributable to the overlap of the excitation wavelength of CdSe with the wavelength where light harvesting is observed. The excellent performance of CdSe/H-TiO2 suggests that this strategy can provide a novel route to design photoactive materials via systematic engineering of light for maximum photoconversion efficiency.

Methods

Fabrication of p-P25 and H-TiO2

In order to fabricate p-P25, a 5 mm × 5 mm size patterned PDMS with 500 nm thickness was prepared from the patterned SU 8 with air holes with diameter of 500 nm and 500 nm in thickness. Scotch tape was attached to the FTO substrate to define the sample size as 5 mm × 5 mm. P25 paste was placed and flattened via the doctor blade method so that paste had uniform height corresponding with that of the scotch tape. The P25 paste was imprinted by the patterned PDMS with proper pressure so that no air bubbles formed. After annealing the samples at 55°C for 45 min to remove the residual solvent, the patterned PDMS and the scotch tape were peeled off. The PDMS can be reused after washing with ethanol. The sample was heated at 500°C for 30 min for calcination, followed by TiCl4 treatment with a concentration of 40 mM at 70°C for 30 min and final heat treatment at 500°C for 30 min. When the st-TIO/FTO substrate was replaced by a FTO substrate, a H-TiO2 structure was created. The fabrication process for the st-TIO substrate is described in the Supporting Information.

Fabrication of CdSe/H-TiO2

The successive ionic layer adsorption and reaction (SILAR) process was used to deposit CdSe onto a H-TiO2/FTO substrate. A sodium selenosulfate (Na2SeSO3) solution was prepared by dissolving 0.01 mol Se powder in a 0.1 M Na2SO3 solution at 90°C for 9 hours. To assemble CdSe onto H-TiO2, the H-TiO2/FTO substrate was dipped into a 50 mM Cd(Ac)2 · 2H2O ethanol solution for 1 min, washed with ethanol for 30 s and then dipped into a Na2SeSO3 solution for 1 min and rinsed with D.I. water for 30 s. Finally, the CdSe/H-TiO2 substrate was dried by blowing nitrogen gas. The two-step dipping procedure is defined as one SILAR cycle. This procedure was repeated twenty times to obtain the desired performance of CdSe and carried out in a glove box filled with nitrogen gas.

Characterization

The morphology of the structures was examined by SEM (NOVA NANOSEM 230 FESEM, 15 kV), TEM (JEM-2100, 200 kV). The powder diffraction data were obtained using a Rigaku Co. High Power X-Ray Diffractometer D/MAZX 2500V/PC from 20° to 80°. Optical properties measurement (Absorbance, Reflection, Transmission) of structures were investigated by UV-visible spectroscopy (VARIAN, Cary 100). The diffuse reflection was measured using a Cary 5000 UV/Vis/NIR. Photoluminescence (PL) spectrum of the CdSe/H-TiO2 was measured by spectrofluorometer (JASCO, FP-8500). Photoconversion efficiency was confirmed using the IPCE measurement system (QEX10, Pv measurements).

PEC measurements

The PEC performance of the TiO2 electrodes was exploited in a three-cell electrode system under front-side illumination of AM 1.5 G (Newport solar simulator) using a potentiostat (Princeton Applied research VersaSTAT3, AMETEK). An Ag/AgCl electrode and a Pt mesh were used as reference and counter electrodes, respectively. A solution of 0.24 M Na2S and 0.35 M Na2SO3 was used as an electrolyte and sacrificial solution. An exposed area of the working electrode was 0.25 cm2. The photoresponse was evaluated under chopped illumination from a Newport solar simulator equipped with an AM 1.5 G filter, calibrated with a standard Si solar cell simulating AM 1.5 G. The power of the solar simulator was measured to be 100 mW/cm2. Photocurrent stability tests were carried out by measuring the photocurrent produced under chopped light irradiation (light/dark cycles of 10 s) at a bias of 0.5 V versus Ag/AgCl. The PEC performances in the visible range were acquired by the solar simulator coupled with a UV cutoff filter (λ > 420 nm) in Figure S5. EIS measurement were performed under the same condition of gas evolutions under illumination of AM 1.5 G.

References

Walter, M. G. et al. Solar Water Splitting Cells. Chem. Rev. 110, 6446–6473 (2010).

Chen, X., Shen, S., Guo, L. & Mao, S. S. Semiconductor-based Photocatalytic Hydrogen Generation. Chem. Rev. 110, 6503–6570 (2010).

Hwang, Y. J., Hahn, C., Liu, B. & Yang, P. D. Photoelectrochemical Properties of TiO2 Nanowire Arrays: A Study of the Dependence on Length and Atomic Layer Deposition Coating. ACS Nano 6, 5060–5069 (2012).

Chouhan, N. et al. Photoelectrochemical Cells for Hydrogen Generation. Electrochemical Technologies for Energy Storage and Conversion. 541–599 (2011).

Luo, J. et al. Homogeneous photosensitization of complex TiO(2) nanostructures for efficient solar energy conversion. Sci Rep 2, 451 (2012).

Brune, A. et al. Porphyrin-Sensitized Nanoparticulate TiO2 as the Photoanode of a Hybrid Photoelectrochemical Biofuel Cell. Langmuir 20, 8366–8371 (2004).

Kisch, H. Semiconductor Photocatalysis–Mechanistic and Synthetic Aspects. Angew. Chem.-Int. Edit. 52, 812–847 (2013).

Lu, Y., Yu, H., Chen, S., Quan, X. & Zhao, H. Integrating Plasmonic Nanoparticles with TiO2 Photonic Crystal for Enhancement of Visible-Light-Driven Photocatalysis. Environ. Sci. Technol. 46, 1724–1730 (2012).

Paramasivam, I., Jha, H., Liu, N. & Schmuki, P. A Review of Photocatalysis using Self-organized TiO2 Nanotubes and Other Ordered Oxide Nanostructures. Small 8, 3073–3103 (2012).

Fan, W., Zhang, Q. & Wang, Y. Semiconductor-based nanocomposites for photocatalytic H2 production and CO2 conversion. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 15, 2632–2649 (2013).

Su, L. T. et al. Photon Upconversion in Hetero-nanostructured Photoanodes for Enhanced Near-Infrared Light Harvesting. Adv. Mater. 25, 1603–1607 (2013).

Bingham, S. & Daoud, W. A. Recent advances in making nano-sized TiO2 visible-light active through rare-earth metal doping. J. Mater. Chem. 21, 2041–2050 (2011).

Kamegawa, T., Matsuura, S., Seto, H. & Yamashita, H. A Visible-Light-Harvesting Assembly with a Sulfocalixarene Linker between Dyes and a Pt-TiO2 Photocatalyst. Angew. Chem.-Int. Edit. 52, 916–919 (2013).

Xu, Z. & Yu, J. Visible-light-induced photoelectrochemical behaviors of Fe-modified TiO2 nanotube arrays. Nanoscale 3, 3138–3144 (2011).

Park, J. H., Kim, S. & Bard, A. J. Novel carbon-doped TiO2 nanotube arrays with high aspect ratios for efficient solar water splitting. Nano Lett. 6, 24–28 (2006).

Xiong, Z. G. & Zhao, X. S. Nitrogen-Doped Titanate-Anatase Core-Shell Nanobelts with Exposed {101} Anatase Facets and Enhanced Visible Light Photocatalytic Activity. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 134, 5754–5757 (2012).

Lee, J., Mubeen, S., Ji, X., Stucky, G. D. & Moskovits, M. Plasmonic Photoanodes for Solar Water Splitting with Visible Light. Nano Lett. 12, 5014–5019 (2012).

Murdoch, M. et al. The effect of gold loading and particle size on photocatalytic hydrogen production from ethanol over Au/TiO2 nanoparticles. Nat. Chem. 3, 489–492 (2011).

Ahn, H.-J. et al. An optimal substrate design for SERS: dual-scale diamond-shaped gold nano-structures fabricated via interference lithography. Nanoscale. 5, 1836–1842 (2013).

Jung, M.-H. & Kang, M. G. Enhanced photo-conversion efficiency of CdSe-ZnS core-shell quantum dots with Au nanoparticles on TiO2 electrodes. J. Mater. Chem. 21, 2694–2700 (2011).

Cheng, C. et al. Quantum-Dot-Sensitized TiO2 Inverse Opals for Photoelectrochemical Hydrogen Generation. Small 8, 37–42 (2012).

Liu, G. et al. A red anatase TiO2 photocatalyst for solar energy conversion. Energy Environ. Sci. 5, 9603–9610 (2012).

Liu, L., Wang, G., Li, Y., Li, Y. & Zhang, J. CdSe quantum dot-sensitized Au/TiO2 hybrid mesoporous films and their enhanced photoelectrochemical performance. Nano Res. 4, 249–258 (2011).

Chen, X., Liu, L., Yu, P. Y. & Mao, S. S. Increasing Solar Absorption for Photocatalysis with Black Hydrogenated Titanium Dioxide Nanocrystals. Science 331, 746–750 (2011).

Lee, S.-H. et al. Coupling of Titania Inverse Opals to Nanocrystalline Titania Layers in Dye-Sensitized Solar Cells. J. Phys. Chem. B 112, 14415–14421 (2008).

Zhang, Z. et al. Plasmonic Gold Nanocrystals Coupled with Photonic Crystal Seamlessly on TiO2 Nanotube Photoelectrodes for Efficient Visible Light Photoelectrochemical Water Splitting. Nano Lett. 13, 14–20 (2012).

Foster, S. & John, S. Light-trapping in dye-sensitized solar cells. Energy Environ. Sci. 6, 2972–2983 (2013).

Kim, J. et al. Nanopatterning of Mesoporous Inorganic Oxide Films for Efficient Light Harvesting of Dye-Sensitized Solar Cells. Angew. Chem.-Int. Edit. 51, 6864–6869 (2012).

Ahn, H.-J. et al. Power conversion efficiency enhancement based on the bio-inspired hierarchical antireflection layer in dye sensitized solar cells. Nanoscale 4, 4464–4469 (2012).

Munday, J. N. & Atwater, H. A. Large Integrated Absorption Enhancement in Plasmonic Solar Cells by Combining Metallic Gratings and Antireflection Coatings. Nano Lett. 11, 2195–2201 (2010).

Wang, K. et al. Absorption Enhancement in Ultrathin Crystalline Silicon Solar Cells with Antireflection and Light-Trapping Nanocone Gratings. Nano Lett. 12, 1616–1619 (2012).

Zhang, Q., Uchaker, E., Candelaria, S. L. & Cao, G. Nanomaterials for energy conversion and storage. Chem. Soc. Rev. 42, 3127–3171 (2013).

Thiyagarajan, P. et al. Hierarchical Metal/Semiconductor Nanostructure for Efficient Water Splitting. Small 9, 2341–2347 (2013).

Colvin, V. L. From Opals to Optics: Colloidal Photonic Crystals. MRS Bull. 26, 637–641 (2001).

Kim, K. et al. Optimization for Visible Light Photoelectrochemical Hydrogen Generation: Gold-Coated and Surface-Textured TIO Nano-Networks. Nanoscale 5, 6254–6260 (2013).

Stavenga, D. G., Foletti, S., Palasantzas, G. & Arikawa, K. Light on the moth-eye corneal nipple array of butterflies. Proc. R. Soc. B-Biol. Sci. 273, 661–667 (2006).

Li, H., Jiang, B., Schaller, R., Wu, J. & Jiao, J. Antireflective Photoanode Made of TiO2 Nanobelts and a ZnO Nanowire Array. J. Phys. Chem. C 114, 11375–11380 (2010).

Luo, J. et al. TiO2/(CdS, CdSe, CdSeS) Nanorod Heterostructures and Photoelectrochemical Properties. J. Phys. Chem. C 116, 11956–11963 (2012).

Hensel, J., Wang, G., Li, Y. & Zhang, J. Z. Synergistic Effect of CdSe Quantum Dot Sensitization and Nitrogen Doping of TiO2 Nanostructures for Photoelectrochemical Solar Hydrogen Generation. Nano Lett. 10, 478–483 (2010).

Karuturi, S. K. et al. Inverse opals coupled with nanowires as photoelectrochemical anode. Nano Energy 1, 322–327 (2012).

Gao, X.-F., Sun, W.-T., Ai, G. & Peng, L.-M. Photoelectric performance of TiO2 nanotube array photoelectrodes cosensitized with CdS/CdSe quantum dots. Appl. Phys. Lett. 96, 153104–3 (2010).

Shin, K., Seok, S. I., Im, S. H. & Park, J. H. CdS or CdSe decorated TiO2 nanotube arrays from spray pyrolysis deposition: use in photoelectrochemical cells. Chem. Commun. 46, 2385–2387 (2010).

Seol, M. et al. Highly Efficient and Stable Cadmium Chalcogenide Quantum Dot/ZnO Nanowires for Photoelectrochemical Hydrogen Generation. Chem. Mat. 25, 184–189 (2012).

Jung, M. & Kang, M. Enhanced photo-conversion efficiency of CdSe–ZnS core–shell quantum dots with Au nanoparticles on TiO2 electrodes. J. Mater. Chem. 21, 2694–2700 (2011).

Acknowledgements

This work is supported by NRF with the contract no. NRF-2010-0019408 and NRF-R1A1A2043076 and by the development program of local science park funded by the ulsan metropolitan city and the MSIP.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The experiments were designed by K.K. and M.K. with suggestions from J.J.; K.K. prepared H-TiO2 samples. K.K. and M.K. performed PEC and optical property measurements. S.K. performed BET ananlysis and EIS measurements. J.J. analyzed the data and wrote the manuscript. All authors discussed the results and commented on the manuscript

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary Information

supporitng information

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Kim, K., Kim, MJ., Kim, SI. et al. Towards Visible Light Hydrogen Generation: Quantum Dot-Sensitization via Efficient Light Harvesting of Hybrid-TiO2. Sci Rep 3, 3330 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep03330

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/srep03330

This article is cited by

-

CuInS/ZnS quantum dots-sensitized solar cells by introducing ZnS passivation layer

Journal of Materials Science: Materials in Electronics (2023)

-

Quantum Dots as Efficient Solar Energy Absorber: Review on Photovoltaics and Photoelectrochemical Systems

Journal of The Institution of Engineers (India): Series D (2023)

-

Fabrication and photoelectrochemical activity of hierarchically Porous TiO2–ZnO heterojunction film

Journal of Materials Science (2020)

-

Low field magneto-tunable photocurrent in CoFe2O4 nanostructure films for enhanced photoelectrochemical properties

Scientific Reports (2018)

-

Nano gold-coated surface patterned mesoporous titanium tin oxide sol–gel thin film: fabrication, optical and photoelectrochemical properties

Journal of Sol-Gel Science and Technology (2018)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.