Abstract

BaTiO3 has a giant electrocaloric strength, |ΔT|/|ΔE|, because of a large latent heat and a sharp phase transition. The electrocaloric strength of a new single crystal, as giant as 0.48 K·cm/kV, is twice larger than the previous best result, but it remarkably decreased to 0.18 K·cm/kV after several times of thermal cycles accompanied by alternating electric fields, because the field-induced phase transition and domain switching resulted in numerous defects such as microcracks. The ceramics prepared from nano-sized powders showed a high electrocaloric strength of 0.14 K·cm/kV, comparable to the single crystals experienced electrocaloric cycles, because of its unique microstructure after proper sintering process. Moreover, its properties did not change under the combined effects of thermal cycles and alternating electric fields, i.e. it has both large electrocaloric effect and good reliability, which are desirable for practical applications.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Electrocaloric (EC) effect is a basic feature of ferroelectrics, referring to changes in entropy and temperature caused by electric field-induced variation of polarization states. In recent years, the attentions on EC effect grow rapidly, because the discovery of giant EC effects is promising to meet the needs in microelectronic and microelectromechanical devices for energy-efficient and environmental friendly solid-state refrigeration1. In 2006, a giant EC effect of ΔTmax = 12 K, nearly an order of magnitude higher than before, was observed in PbZr0.95Ti0.05O3 thin films2, after that giant EC effects have been reported for various ferroelectric ceramic and polymer films3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12. Although the EC effect in thin films is greatly enhanced under ultrahigh fields of hundreds kV/cm, the EC strength |ΔT|/|ΔE| reduces at the same time, even lower than that of the bulk counterparts, including single crystal (SC) and ceramics13,14,15,16.

Recently, giant EC strengths were obtained in BaTiO3 SCs near the first order phase transitions (FOPT) in our previous work (0.24 K·cm/kV@5 kV/cm and 0.16 K·cm/kV@10 kV/cm)13,14 and in Moya's report (0.22 K·cm/kV@4 kV/cm)15. However, the low reliability of SC works against the practical applications. It was reported that cracks tend to nucleate and propagate in ferroelectric SCs because of the incompatible strain during the electric-field-induced (and/or temperature) domain switching17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24. This paper experimentally demonstrated the giant EC strength of BaTiO3 SCs and its rapid degradation with thermal cycles and alternating electric fields. More important, both high reliability and giant EC strength were achieved in BaTiO3 ceramics prepared from hydrothermal synthesized nano-sized powders, whose performances were comparable to the used SCs and far beyond the conventional ceramics.

Results

Previous reports indicated that the EC effect near a FOPT is dominated by the energy change associated with the change of lattice structure, which can be two orders of magnitude higher than the entropy change of dipolar order13, while the sharpness of the transition is the key to a giant EC strength15. A perfect SC without defects behaves as an ideal crystal, where all lattice have the same energy barrier in phase transition and domain switching, so it will show a giant EC strength near FOPT.

The P-E loops of a new BaTiO3 SC at different temperatures are shown in Fig. 1a. Besides an expected drop of polarization with increasing temperature (Fig. 1b), the normal hysteresis loop becomes double loop between 407 K and 413 K (Fig. 1c). The double hysteresis loop originates from a typical electric-field-induced phase transition (EFIPT) from paraelectric (P) to ferroelectric (F) phase25, not as that in aged BaTiO3 SCs assumed by Ren26. The double loop appears above T1 in Landau-Devonshire (LD) theory, i.e. the highest temperature where the low-temperature phase exists in a metastable state under zero-field. Here, T1 = 407 K is confirmed by both P-E loops and heat flow curves. The occurrence of double loop with regular shape indicates that there is little energy fluctuation in a new SC and the EFIPT carries out in all lattices uniformly. The good consistency of the phase transition is also reflected by the horizontal heat flow curve below T1 (inset in Fig. 1d). With increasing temperature, the critical field increases, indicating the ease of an EFIPT; while the width of one loop decreases, indicating the stability of the field-induced phase. This reflects the competition between the field-induced polarization order and the thermally excited disorder. The double loop disappears above 415 K, implying that external fields cannot induce phase transition any more, i.e. T2 in LD theory.

Based on the Maxwell relation, (∂P/∂T) = (∂S/∂E), the EC adiabatic temperature change ΔT for a material with density ρ and heat capacity C can be calculated by

At 10 kV/cm field, ΔT reaches a maximum at 409 K, a bit higher than the phase transition temperature and ΔTmax = 4.8 K is much higher than those in the previous reports, including that in our works (1.6 K@10 kV/cm)14 and those in Moya's reports (0.9 K@12 kV/cm and 0.87 K@4 kV/cm)15. In addition, the EC strength is as giant as |ΔT|/|ΔE| = 0.48 K·cm/kV, twice larger than the previous best result1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,27.

However, the large amount of defects, such as microcracks, will occur in SC after several times of thermal cycles accompanied by alternating electric field cycles because of the incompatible strain during the lattice deformation17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24. (Hereafter, one EC cycle refers to a heating and cooling process from room temperature to 430 K, where three times of cycling electric fields were applied at certain temperatures.) As shown in Fig. 2a, there are alternately dark and bright domain stripes and no microcrack in a new SC. After several EC cycles, more and more microcracks nucleate parallel to domain strips and then propagate (Fig. 2b, 2c). The P-E loop becomes fatter and shorter (Fig. 2d) and P drops with increasing EC cycles (Fig. 2e), because the defects obstacle the domain switching and induce depolarization fields and the cracks reduce the fields in the sample28,29,30. In addition, the energy fluctuation is enhanced and the sharpness of phase transition is weakened, therefore the double loop occurs more difficult in a smaller temperature range and the shape is irregular (Fig. 2f). As a result, ΔTmax drops dramatically to 1.8 K after several EC cycles (Fig. 2g), whose value is also confirmed by direct entropy change measurements either on heat capacity or on heat flow and is in agreement with the literature values14,15. It implies that new BaTiO3 SC has very outstanding EC performance but it is unreliable.

Ferroelectric and EC properties of the used SC, as well the evolution of microstructure with EC cycles.

(a) P-E loops at different temperatures; (b) a comparison of room-temperature P-E loops between new and used SC; (c) P-T curves in a serial of EC cycles; (d) the variation of ΔTmax with EC cycles; (e) the microstructure of the new SC before measurements, (f) after one EC cycle and (g) after five EC cycles.

Although the degradation of EC performance in SC may be slowed down gradually (Fig. 2g), some irreversible effects appear, such as low fracture strength, easy breakdown and bad insulation. The bad insulation is reflected as the increase of apparent Pr above the phase transition temperature.

The polycrystalline ceramics have much better reliability than that of SCs because the grain boundaries buffer the stress during domain switching. The BaTiO3 ceramics also show typical ferroelectric hysteresis loops (Fig. 3a), but the polarization and EC effect keep steady after EC cycles (Fig. 3b), indicating good reliability. In addition, large amount of grain boundaries and pores are defects in the microstructures to reduce the polarization and enhance the energy fluctuation, so there is no double hysteresis loop (Fig. 3a) in the conventional ceramics (M-Ceram) prepared from ~1 μm starting powders by a solid-state reaction method and the EC ΔTmax is as low as 0.5 K (Fig. 3c).

To retain good reliability and enhance EC effect, the microstructure of ceramics was modified by using hydrothermal synthesized powders with average size of ~35 nm (N-Ceram). The N-Ceram samples show both typical ferroelectric hysteresis loops (Fig. 3d) and high reliability (Fig. 3e) similar to those of M-Ceram. However, its EC effect, ΔTmax = 1.4 K, is much stronger than that of M-Ceram (Fig. 3f), which results from its unique microstructures.

The highly active nano-sized powders make the N-Ceram samples densified at a relatively low temperature of 1200°C (Fig. 4a). As the sintering temperature further rises to 1250°C, small grains integrate together and the boundaries become blurry (Fig. 4b). The blurry grain boundaries imply less lattice mismatch between neighboring grains, which are not found in the M-Ceram sample (Fig. 4c). The decrement of defects in the sintered ceramics reduces the obstacles for the domain switching and lowers the energy fluctuation, so the P-E loops become more saturated (Fig. 4d), the endothermic peak becomes sharper (Fig. 4e) and the double P-E loop appears near the FOPT (Fig. 3d). Hence, N-Ceram sintered at 1250°C shows a large EC of ΔTmax = 1.4 K at 10 kV/cm field (Fig. 3f), i.e. a giant EC strength of 0.14 K·cm/kV. The EC strength is much higher than that of all conventional ceramics1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16 and relaxor SCs (such as PMN-PT)27 and is comparable to the used BaTiO3 SCs.

Discussion

The heat low curves indicate that M-Ceram, N-Ceram and single crystals have similar latent heat about 0.90 ± 0.02 J/g, in agreement with literature15,31,32, but the sharpness of the endothermic peaks increases in turn (Fig. 4b). It indicates that the obvious differences in microstructure do not affect the total energy change of lattice structure at a FOPT, but influence the sharpness of the transition which determines the peak value of EC effects. Among all samples examined, N-Ceram shows both high EC effect and good reliability because its unique microstructures have fewer defects except for blurry grain boundaries.

Methods

Preparation of BaTiO3 samples

The (001) BaTiO3 single crystal was a commercially available product (Physcience Opto-Electronics Co., China). BaTiO3 ceramics were fabricated by conventional ceramics method, using hydrothermal synthesized nano-sized powders and solid-state reacted micron-sized powders, respectively.

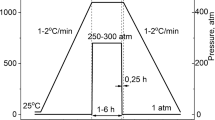

In hydrothermal syntheses method, the HCl solution of 15.0% TiCl3 was added into the aqueous solution of BaCl2·2H2O based on an initial precursor molar ratio Ba/Ti of 1.6 and the pH was adjusted to 13.5 by adding 10 mol/L KOH solution. It was crystallized at 150°C for 8 h in an autoclave. After cooling down to room temperature, the pH was adjusted to 6.0. The final powders were obtained after filtration, wash and drying at 105°C. In solid-state reaction method, the raw materials of analytical reagent grade BaCO3, CaCO3, ZrO2 and TiO2 were mixed and calcined at 1000°C. Using the hydrothermal synthesized nano-sized powders or solid-state reacted micron-sized powders, the dry-pressed pellets were sintered at 1200–1350°C in air.

Characterization of BaTiO3 single crystal and ceramics

The ferroelectric hysteresis loop was measured at 10 Hz using a TF2000 analyzer equipped with a temperature controller. The temperature dependence of polarization under certain electric field was extracted data from the upper branch of each loop and then ∂P/∂T was obtained. Reversible adiabatic temperature change ΔT was calculated using Eq. (1).

The domain configuration in BaTiO3 single crystal was observed by polarized light microscopy, while the microstructure of ceramics was observed by scanning electron microscopy. The thermal characters of phase transition were measured within a temperature range of 100–150°C using a differential scanning calorimeter (DSC, TA Instruments Q2000).

References

Lu, S. G. & Zhang, Q. M. Electrocaloric materials for solid-state refrigeration. Adv. Mater. 21, 1983–1987 (2009).

Mischenko, A. S., Zhang, Q., Scott, J. F., Whatmore, R. W. & Mathur, N. D. Giant electrocaloric effect in thin-film PbZr0.95Ti0.05O3 . Science 311, 1270–1271 (2006).

Mischenko, A. S., Zhang, Q., Whatmore, R. W., Scott, J. F. & Mathur, N. D. Giant electrocaloric effect in the thin film relaxor ferroelectric 0.9PbMg1/3Nb2/3O3–0.1PbTiO3 near room temperature. Appl. Phys. Lett. 89, 242912 (2006).

Neese, B. et al. Large electrocaloric effect in ferroelectric polymers near room temperature. Science 321, 821–823 (2008).

Lu, S. G. et al. Electrocaloric effect of the relaxor ferroelectric poly(vinylidene fluoride-trifluoroethylene-chlorofluoroethylene) terpolymer. Appl. Phys. Lett. 97, 162904 (2010).

Chen, H., Ren, T., Wu, X., Yang, Y. & Liu, L. Giant electrocaloric effect in lead-free thin film of strontium bismuth tantalite. Appl. Phys. Lett. 94, 182902 (2009).

Correia, T. M. et al. Investigation of the electrocaloric effect in a PbMg2/3Nb1/3O3-PbTiO3 relaxor thin film. Appl. Phys. Lett. 95, 182904 (2009).

Correia, T. M. et al. PST thin films for electrocaloric coolers. J. Phys. D: Appl. Phys. 44, 165407 (2011).

Bai, Y., Zheng, G. P. & Shi, S. Q. Direct measurement of giant electrocaloric effect in BaTiO3 multilayer thick film structure beyond theoretical prediction. Appl. Phys. Lett. 96, 192902 (2010).

Bai, Y. et al. The giant electrocaloric effect and high effective cooling power near room temperature for BaTiO3 thick film. J. Appl. Phys. 110, 094103 (2011).

Feng, Z., Shi, D. & Dou, S. Large electrocaloric effect in highly (001)-oriented 0.67PbMg1/3Nb2/3O3–0.33PbTiO3 thin films. Solid State Comm. 151, 123–126 (2011).

Chukka, R. et al. Enhanced cooling capacities of ferroelectric materials at morphotropic phase boundaries. Appl. Phys. Lett. 98, 242902 (2011).

Bai, Y. et al. The electrocaloric effect around the orthorhombic-tetragonal first-order phase transition in BaTiO3 . AIP Adv. 2, 022162 (2012).

Bai, Y., Ding, K., Zheng, G. P., Shi, S. Q. & Qiao, L. J. Entropy-change measurement of electrocaloric effect of BaTiO3 single crystal. Phys. Status Solidi A 209, 941–944 (2012).

Moya, X. et al. Giant electrocaloric strength in single-crystal BaTiO3 . Adv. Mater. 25, 1360–1365 (2013).

Luo, L., Dietze, M., Solterbeck, C. H., Es-Souni, M. & Luo, H. Orientation and phase transition dependence of the electrocaloric effect in 0.71PbMg1/3Nb2/3O3–0.29PbTiO3 single crystal. Appl. Phys. Lett. 101, 062907 (2012).

Jiang, B. et al. Delayed crack propagation in barium titanate single crystals in humid air. J. Appl. Phys. 103, 116102 (2008).

Wang, F., Su, Y. J., He, J. Y., Qiao, L. J. & Chu, W. Y. In situ AFM observation of domain switching and electrically induced fatigue cracking in BaTiO3 single crystal. Script. Mater. 54, 201–205 (2006).

Busche, M. J. & Hsia, K. J. Fracture and domain switching by indentation in barium titanate single crystals. Script. Mater. 44, 207–212 (2001).

Fang, F., Yang, W., Zhang, F. C. & Luo, H. S. Fatigue crack growth for BaTiO3 ferroelectric single crystals under cyclic electric loading. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 88, 2491–2497 (2005).

Busche, M. J. & Hsia, K. J. Fracture and domain switching by indentation in barium titanate single crystals. Script. Mater. 44, 207–212 (2001).

Schneider, G. A. & Heyer, V. Influence of the electric field on Vickers indentation crack growth in BaTiO3 . J. Euro. Ceram. Soc. 19, 1299–1306 (1999).

Snoecka, E., Normandab, L., Thorelab, A. & Roucaua, C. Electron microscopy study of ferroelastic and ferroelectric domain wall motions induced by the in situ application of an electric field in BaTiO3 . Phase Tansit. 46, 77–88 (1994).

Pramanick, A., Jones, J. L., Tutuncu, G., Ghosh, D., Stoica, A. D. & An, K. Strain incompatibility and residual strains in ferroelectric single crystals. Sci. Rep. 2, 929 (2012).

Merz, W. J. Double hysteresis loop of BaTiO3 at the curie point. Phys. Rev. 91, 513–517 (1953).

Ren, X. Large electric-field-induced strain in ferroelectric crystals by point-defectmediated reversible domain switching. Nat. Mater. 3, 91–95 (2004).

Novak, N., Pirc, R. & Kutnjak, Z. Impact of critical point on piezoelectric and electrocaloric response in barium titanate. Phys. Rev. B 87, 104102 (2013).

Nuffer, J., Lupascu, D. C. & Rödel, J. Damage evolution in ferroelectric PZT induced by bipolar electric cycling. Acta Mater. 48, 3783–3794 (2000).

Lynch, C. S., Chen, L. & Suo, Z. Crack growth in ferroelectric ceramics driven by cyclic polarization switching. J. Intel. Mater. Sys. Struct. 6, 191–198 (1995).

Cao, H. & Evans, A. G. Electric-field-induced fatigue crack growth in piezoelectrics. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 77, 1783–1786 (1994).

Shirane, G., Danner, H., Pavlovic, A. & Pepinsky, R. Phase Transitions in Ferroelectric KNbO3 . Phys. Rev. 93, 672–673 (1954).

Devonshire, A. F. Theory of barium titanate Part I. Phil. Mag. 40, 1040–1063 (1949).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by grants from the National Science Foundation of China (51172020, 51072021 and 51372018), the Program for New Century Excellent Talents in University (NCET-12-0780) and the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (FRF-TP-09-028A).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.B. designed the experiments and analyzed the results. X.H. prepared the ceramics and characterized all samples. X.C.Z. prepared the nano powders. L.J.Q. guided the work and analysis. Y.B. wrote the paper.

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Bai, Y., Han, X., Zheng, XC. et al. Both High Reliability and Giant Electrocaloric Strength in BaTiO3 Ceramics. Sci Rep 3, 2895 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep02895

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/srep02895

This article is cited by

-

Dysprosium doping induced effects on structural, dielectric, energy storage density, and electro-caloric response of lead-free ferroelectric barium titanate ceramics

Journal of Materials Science (2024)

-

Multi-element B-site substituted perovskite ferroelectrics exhibit enhanced electrocaloric effect

Science China Technological Sciences (2023)

-

Materials, physics and systems for multicaloric cooling

Nature Reviews Materials (2022)

-

Electro-caloric effects in the BaTiO3-based solid solution ceramics

Journal of the Korean Ceramic Society (2020)

-

Giant electrocaloric response in smectic liquid crystals with direct smectic-isotropic transition

Scientific Reports (2019)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.