Abstract

With atomic systems, optically programmed trapping potentials have led to remarkable progress in quantum optics and quantum information science. Programmable trapping potentials could have a similar impact on studies of semiconductor quasi-particles, particularly excitons. However, engineering such potentials inside a semiconductor heterostructure remains an outstanding challenge and optical techniques have not yet achieved a high degree of control. Here, we synthesize optically programmable trapping potentials for indirect excitons of bilayer heterostructures. Our approach relies on the injection and spatial patterning of charges trapped in a field-effect device. We thereby imprint in-situ and on-demand electrostatic traps into which we optically inject cold and dense ensembles of excitons. This technique creates new opportunities to improve state-of-the-art technologies for the study of collective quantum behavior of excitons and also for the functionalisation of emerging exciton-based opto-electronic circuits.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In semiconductors, spatially indirect excitons of bilayer heterostructures, e.g. of double quantum wells, provide a model example of dipolar quantum particles1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8. To explore the exotic collective quantum phenomena predicted for indirect excitons9,10,11 studies have emphasized the creation of trapping potentials12,13,14,15,16,17,18 and gate defined electrostatic traps have led so far to the most advanced realizations6,19,20,21,22,23. This technology relies on the dipolar interaction between the well oriented electric dipole of indirect excitons and a spatially varying electric field controlled by the gate electrodes. In electrostatic traps, indirect excitons are usually created by optically injecting electronic carriers, a process which can alter basic functionalities. For example, the optical injection of electrons and holes can result in carrier imbalance23, even in a spatial separation of charges24,25. We have also shown recently that photo-injected carriers can accumulate at the gate electrodes and then blur the excitons confinement26. Here we show that the disruptive role of photo-injected carriers can be tailored in a way that yields an electro-optic control over the confinement of indirect excitons.

Results

Photo-excitation of the field-effect device

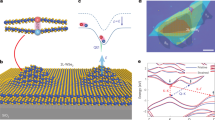

We studied indirect excitons confined in a GaAs double quantum well (DQW) embedded in a n-i-n field-effect device (see Figure 1.A and Methods). For this heterostructure we developped an all-optical control over the excitons confinement using sequences of pulsed laser excitations. Our approach relies first on a “preparation” beam tuned at 641.5 nm, i.e. at an energy slightly below the bandgap of the Al0.33Ga0.67As barriers surrounding the DQW27. Thus, we used a “preparation” pulse to inject electronic carriers mainly in the n-doped contact electrodes, a small part of the “preparation” beam being also directly absorbed by the DQW28. While most of the carriers created in the contacts generate a photo-current, a smaller fraction also produces an out-of-equilibrium population of charges accumulated at the n-i heterojunctions due to the potential barriers formed by the band offset between the n-GaAs and Al0.33Ga0.77As layers29. At 350 mK, our bath temperature, the thermal activation may be too small (kBT ~ 30 μeV) to overcome the potential barriers such that charges can remain accumulated at the n-i heterojunctions after a “preparation” pulse and then dress the internal electric field26.

(A) Sketch of the field-effect device energy levels.Electrons and holes are represented by full and open circles respectively, “preparation” and “writing” beams by the blue and red arrows respectively. The optical excitation is performed from the surface of the sample where the gate Vg is applied (right side). The grey areas underline the heterojunctions where photo-injected carriers can accumlate. (B) Variation of the energy (ΔEX in black circles) and spectral width (ΓX in red squares) of the indirect excitons photoluminescence as a function of the power of the “preparation” beam,  where

where  is the emission energy without “preparation” pulse. The inset shows the variation of the mean photo-current in these measurements. (C) Spatially and spectrally resolved emission of indirect excitons loaded by a probe pulse (at 8.5 mW.cm−2) turned on 500 ns after a “preparation” pulse of 10 μm waist and power equal to 100 mW.cm−2. The white line displays the profile of the “preparation” beam. All measurements were realized 20 ns after extinction of the probe pulse in a 20 ns wide time window and at 350 mK.

is the emission energy without “preparation” pulse. The inset shows the variation of the mean photo-current in these measurements. (C) Spatially and spectrally resolved emission of indirect excitons loaded by a probe pulse (at 8.5 mW.cm−2) turned on 500 ns after a “preparation” pulse of 10 μm waist and power equal to 100 mW.cm−2. The white line displays the profile of the “preparation” beam. All measurements were realized 20 ns after extinction of the probe pulse in a 20 ns wide time window and at 350 mK.

Mapping the internal electric field with indirect excitons

We first quantified the influence of the “preparation” beam on the amplitude of the internal electric field, Eint, by using a pump-probe sequence where a 300 ns long “preparation” pump pulse was followed 500 ns later by a weak excitation probe, from another laser beam at 790 nm. The probe excitation was tuned resonantly with the direct excitonic transition of the two quantum wells in order to inject electrons and holes directly in the DQW which then create a dilute gas of indirect excitons. The internal electric field is also weakly perturbed by the probe excitation, the photoluminescence emitted by the n-doped contacts being negligible compared to that obtained by excitation with the “preparation” beam. In these experiments, indirect excitons injected by the probe pulse served as a sensitive and non-perturbative probe for Eint: in the dilute regime, the indirect exciton emission energy, EX, is governed by the dipolar interaction between the excitonic dipole oriented perpendicularly to the DQW, d ≈ e.10 nm (data not shown) and the internal field, such that EX scales like (−d.Eint).

For our field-effect device, we observed that the amplitude of the internal electric field is significantly enhanced by the “preparation” excitation (see Fig. 1.B). This is manifested by a red shift of EX with increasing power of the “preparation” beam (P640), in agreement with an accumulation of carriers at the contact electrodes (note that the injection of holes results in a deficit of electrons increasing the potential of the bottom electrode on the left hand-side of Fig. 1.A). However, we note that the red shift of EX saturates at ≈ −4 meV which indicates that the charge accumulation can become too large to be blocked efficiently by the potential barrier at the heterojunctions. Indeed, the saturation of EX coincides with a steep increase of the mean photocurrent (see inset in Fig. 1.B).

Quite surprisingly, we also noted a strong lateral localization of excess charges over long timescales. This behavior was signaled by experiments where we used a narrow “preparation” beam (10 μm waist) while the probe beam was wide (~ 67 μm waist). Then, 20 ns after the end of the probe pulse, the spatially and spectrally resolved emission of indirect excitons reveals that EX is shifted to lower energies under the “preparation” beam excitation area, by Δt ~ 1.7 meV, while outside the emission occurs at a rather unperturbed energy. This manifests that the charge accumulation lasts for several hundreds of nanoseconds and also that the carriers lateral diffusion is very slow, probably due to the n-i interface roughness which localizes excess charges, particularly at our sub-Kelvin bath temperature. Accordingly, the “preparation” pulse has imprinted an electrostatic trap with a depth (Δt) almost two orders of magnitude greater than the thermal activation energy.

Programming the confinement of indirect excitons

To increase our degree of control over the excitons' confinement, we included a “writing” pulse in our laser sequence. The “writing” beam was produced by another laser diode emitting at ~790 nm and had a two-fold purpose: Firstly, above a threshold excitation the “writing” beam leads to a heating of our sample to about ten degrees Kelvin30, heating which can activate the transport of carriers accumulated at the contacts after an excitation by the “preparation” pulse. Secondly, the “writing” pulse allowed us to inject indirect excitons directly in the DQW while it is weakly absorbed by the contact electrodes, as for the probe excitation.

The heating of our sample by the “writing” beam is revealed by the dynamics of the photoluminescence emitted by indirect excitons at the end of a pulsed excitation (note that the “preparation” beam was not used here). Indeed, indirect excitons constitute a sensitive probe of the sample's temperature as they experience a rapid thermalization in our two-dimensional geometry30,31,32,33,34. Figure 2. A–D illustrates the exciton thermometry and shows that the photoluminescence emitted at the position of the “writing” beam suddenly increases, or jumps, at the end of a laser pulse. By contrast, 10 μm outside the illuminated region this non-linearity is strongly reduced. These distinct dynamics underline the collapse of the so-called inner-ring, i.e. the thermalization within few nano-seconds of indirect excitons that were heated during the “writing” pulse and within the illuminated region30,31,32,33,34. On the other hand, outside of the laser spot the photoluminescence jump is reduced which shows that this region was weakly heated during the laser excitation.

(A–B) Spatially and spectrally resolved emission of indirect excitons at the falling edge (A) and 4 ns after (B) a “writing” pulse at 10 W.cm−2 and with a 6 μm waist.The beam is positioned at the center (position 0). (C) Emission profiles at the falling edge of the writing pulse and 4 ns later, solid and dotted lines respectively (the laser profile is shown by the red line). (D) Dynamics of the photoluminescence intensity at the position of the “writing” pulse (red) and outside (blue). The black line shows the best fit which yields a mono-exponential decay with a time constant equal to 138(3) ns. All measurements were realized with a 2 ns time resolution and at 350 mK.

The effect of the “writing” beam onto the spatial distribution of carriers injected by a “preparation” pulse and trapped at the n-doped contacts is illustrated in Fig. 3. A–E. For these experiments we excited the field-effect device using a 8 μm wide “writing” beam positioned at the center of a large (≈80 μm waist) “preparation” beam. Also, the delay between the “writing” and “preparation” pulses was set to 500 ns (Fig. 3.A). As shown in Figure 3.B, the emission of indirect excitons then exhibits a ring-shaped pattern 20 ns after the “writing” pulse. The inner dark region has a spatial profile reproducing closely the “writing” beam shape: there the photoluminescence has dropped by ~50% compared to a reference situation where no “preparation” beam is used (see Fig. 3.C–D). Incidentally, we note for this reference case that the emission has a spatial extension much larger than the “writing” beam (see Fig. 3.D): strong repulsive dipolar interactions between indirect excitons induce a large exciton diffusion32,35.

(A) Sketch of our laser sequence where 300 ns long “preparation”, “writing” and probe pulses are each separated by a 500 ns waiting time.The variation of the confining potential during the sequence is schematically displayed at the position the DQW (shown in orange) together with the charges accumulated at the top and bottom electrodes. (B–C) Photoluminescence emission of indirect excitons 20 ns after termination of the “writing” pulse (8 μm waist and at 1.5 W.cm−2) with (B) and without (C) excitation by a “preparation” pulse (at 15 mW.cm−2). (D) Intensity profiles taken at the center of the images (B) and (C), solid and dashed lines respectively, together with the profile of the “writing” beam (red line). (E) Spatially and spectrally resolved emission of indirect excitons 20 ns after extinction of the probe pulse. Δat ≈ 2 meV marks the amplitude of the anti-trapping potential and the white line displays the profile of the “writing” beam. All measurements were realized 20 ns after extinction of the “writing” (B–D) or probe (E) pulse in a 20 ns wide time window and at 350 mK.

The occurrence of the ring pattern in Fig. 3.B indicates that the central region is now a region where the internal field is low and from where the excitons are dragged away, indirect excitons being high-field seekers. To confirm this interpretation and measure the potential step for indirect excitons, a third probe beam was used and switched on 500 ns after extinction of the “writing” pulse (see Fig. 3.A). The spatial and spectral mapping of the indirect excitons photoluminescence was measured 20 ns after the probe pulse. As shown in Fig. 3.E we then observed that the emission occurs at a higher energy at the “writing” beam position than in the surrounding, by Δat ≈ 2 meV. This measurement confirms directly that the amplitude of the internal field is reduced in the region illuminated by the “writing” beam. Hence, carriers injected by the “preparation” beam and trapped at the contacts have been depleted from this region by the “writing” pulse and we thus created a potential gradient expelling indirect excitons away from the beam position, i.e. a quasi-stationnary anti-trap with a height Δat.

Hollow trap for indirect excitons

The previous technique can be easily extended to realize a hollow-trap for indirect excitons. Such trap consists of a ring-shaped potential barrier36. To engineer it, we solely shaped the “writing” beam into a ring (Fig. 4.A). Again we used a sequenced optical control where a spatially wide and uniform “preparation” pulse was followed by a ring-shaped “writing” pulse. We present in Fig. 4.B the spatially resolved emission 20 ns after the “writing pulse” when the field-effect device was not illuminated by the “preparation” beam. No trace of the “writing” beam shape is observed owing to the large diffusion of indirect excitons. On the contrary, when the sample is first illuminated by a “preparation” pulse (Fig. 4.C), the emission, 20 ns after the end of the “writing” pulse, is more intense (same color scale as in Fig. 4.B) and localized within the area defined by the “writing” beamshape. The writing pulse has defined a hollow-trap for excitons and built up a population of indirect excitons which relax rapidly toward the trap center. As shown in Fig. 4.D, this excitation scheme is efficient to create and confine a dense ensemble as the photoluminescence increases by as much as 30% at the center of the trap (see the blue area).

(B–C) Photoluminescence emission of indirect excitons for the ring-shaped “writing” beam shown in the panel (A) (18 μm radius and 3 μm width at 0.75 W.cm−2) without (B) and with (C) excitation of the field effect device by a “preparation” pulse with 50 μm waist (at 3.8 mW.cm−2).(D) Intensity profiles taken at the center of the images displayed in (B) and (C), dashed and solid lines respectively, together with the profile of the “writing” beam (red line). The filled area marks the increase of the photoluminescence when the hollow-trap is imprinted. All measurements were realized 20 ns after extinction of the “writing” pulse in a 20 ns wide time window and at 350 mK.

To further quantify the performance of the hollow-trap barrier, we injected indirect excitons directly at the center of the hollow-trap and monitored the exciton transport as we increased the density. Precisely, we used a complete laser sequence where “preparation” and “writing” pulses first imprinted a hollow trap, 500 ns before we applied a 300 ns long “loading” pulse produced by another laser diode emitting at 790 nm (see Fig. 5.A). The “loading” beam was positioned at the center of the trap and we used its intensity to vary the concentration of excitons confined in the trap. Also, note that the “loading” beam introduced an additonal potential barrier converting the hollow into a ring trap.

(A) Sketch of the laser sequence where 300 ns long “preparation”, “writing” and “loading” pulses are separated by a 500 ns waiting time.The resulting exciton confining potentials are displayed schematically together with the charge accumulation at the contact electrodes. (B–C) Spatially and spectrally resolved photoluminescence of indirect excitons emitted 20 ns after extinction of a “loading” pulse at 1.5 W.cm−2 (B) and 5.6 W.cm−2 (C). The solid white line displays the profile of the ring-shaped “writing” beam and the dash white line the one of the “loading” beam. (D) Intensity profiles for the experiments shown in (B) when the hollow-trap barrier is imprinted (solid red line) or not (dash blue line). The green lines show the profile of the “writing” and “loading” laser beams. (E) Energy, EX, of the photoluminescence emitted by indirect excitons confined in the hollow trap as a function of the power of the “loading” beam. All measurements were realized 20 ns after extinction of the “loading” pulse in a 20 ns wide time window and at 350 mK.

As shown in Figure 5, for the confinement of indirect excitons we can distinguish two regimes as a function of the power of the loading beam (P790). First, for P790 ≤ 1.5 W.cm−2 we note that the exciton transport is well blocked by the hollow trap barrier, as revealed by a drop of the photoluminescence intensity outside the trap (red line in Fig. 5.D) where it is reduced by ≈2-3 times compared to a reference situation where the ring shaped “writing” beam was not used (dashed blue line in Fig. 5.D). By contrast, excitons overflow the hollow-trap barrier for P790 ≥ 1.5 W.cm–2 (Fig. 5.C). In this regime, dipolar interactions between excitons enhance the mean-field energy which overcomes the barrier height30,35. Accordingly, the concentration of excitons confined in the trap saturates, as underlined by the variation of the photoluminescence energy, EX, as a function of power of the “loading” beam (Fig. 5.E). Indeed, while EX is governed by the interaction between the excitons dipole and the internal electric field in the very dilute regime, it reveals the exciton concentration at higher densities where repulsive dipolar interactions between excitons are dominant and yield a blue shift of the photoluminescence emission proportional to the exciton density37,38. As shown in Figure 5.E, in the hollow-trap we observed that EX is enhanced by ≈2 meV before saturating as we increased the power of the “loading” beam. Following recent theoretical works37,38, we deduce that this blue shift corresponds to an exciton density of approximately 5 1010 cm−2, also we note that the maximum blue shift of the photoluminescence emitted in the hollow-trap well agrees with the barrier height (Δat) that we measured by mapping the landscape of the internal electric field (Fig. 3.E).

Discussion

In Figure 1.A we have shown that an excitation by the “preparation” beam red-shifts the photoluminescence emitted by indirect excitons, by up to ≈4 meV. On the other hand, resolving spatially the emission of indirect excitons we have observed that a “preparation” pulse varies the energy of the photoluminescence emission by at most 2 meV. We attribute the discrepancy between these measurements as a manifestation of the injection of electronic carriers in the DQW by the “preparation” beam, notably as a result of the photocurrent generated by a “preparation” pulse. In that respect, previous studies24,25 have underlined that holes are captured more efficiently than electrons for an excitation at the energy of the “preparation” beam so that photo-injected holes can vary the charge of the DQW by (partially) annihilating residual electrons. For a DQW embedded in a field-effect device, such a background electron gas constitutes a typical drawback39 which results from the modulation doping in the structure. Background electrons screen the potential confining indirect excitons38, their annihilation by a “preparation” pulse would then effectively increase the excitons' confinement, i.e. induces a red shift of the photoluminescence. Though we can not quantify this scenario, our experiments have revealed that a “preparation” pulse yields a smoother electrostatic landscape for indirect excitons injected 500 ns later by a probe beam. This is shown in Figure 1.B which underlines that the spectral width of the photoluminescence emitted after the probe pulse, ΓX, drops at low intensities of the “preparation” beam, from ΓX ≈ 2.8 to 1.8 meV. Such a behavior is consistent with the annihilation of residual electrons by the “preparation” beam which then reduces the spectral diffusion.

Methods

Sample structure

We studied a field-effect device consisting of a n-i-n heterostructure embedding a double quantum well (DQW) made of two 8-nm wide GaAs quantum wells separated by a 4-nm Al0.33Ga0.67As barrier. The DQW is placed between two Al0.33Ga0.67As spacers of 200nm thickness. In our experiments, a static potential (Vg = −1.4 V) was applied between two n-GaAs layers (Si doped with nSi ~ 5 × 1017 cm3) which serve as gate electrodes. The top and back gates are 105 nm and 305 nm thick respectively. The back gate is electrically connected with a metallic contact deposited after etching of the sample. In our experiments, this electrode is grounded and electrically isolated from the sample holder by a 800 nm undoped GaAs layer incorporating a AlAs/GaAs superlattice. In addition, the top contact consists of a mesa with a 500 × 500 μm2 aperture through which the photoluminescence is collected.

Experimental setup

The field-effect device was placed on the Helium 3 insert of a closed cycle Helium 4 cryostat (Heliox-ACV from Oxford Instruments). An aspheric lens with a 0.6 numerical aperture was embedded inside the cryostat in front of the sample and positioned by piezo-electric transducers (ML17 from MechOnics-Ag). We optimized the optical resolution of our microscope by introducing a mechanical coupling between the Helium 3 insert and the part holding the aspheric lens. Thus, the amplitude of mechanical vibrations does not exceed 2 microns (in a frequency range up to ~1 kHz) while the sample can be cooled to temperatures as low as 330 mK. In our experiments, the aspheric lens was used to excite the semiconductor sample but also to collect the photoluminescence that was reemitted. The latter was then directed to an imaging spectrograph coupled to an intensified CCD camera (Picostar-UF from La Vision) and we studied the emission of indirect excitons with a 2 ns time resolution at 500 kHz, either in real space or including a spectral resolution of 200 μeV.

To create the laser pulse sequences we used two CW diode lasers (DL-100 from Toptica) at 642 nm (“preparation” beam) and 790 nm (“writing” and probe beams). Both lasers were pulsed with electro-optic (integrated-optical modulator from JenOptic) and acousto-optic modulators (Crystal Technologies Inc.), controlled by a pulse sequencer. Thus, we engineered up to four independent excitation pulses with rising and falling edges of ~2 ns and ~5 ns for the electro-optic and acousto-optic switching respectively.

References

Eisenstein, J. M. & Mac Donald, A. H. BoseEinstein condensation of excitons in bilayer electron systems. Nature 432, 691 (2004).

Nandi, D., Finck, A. D. K., Eisenstein, J. P., Pfeiffer, L. N. & West, K. W. Exciton condensation and perfect Coulomb drag. Nature 488, 481 (2012).

High, A. A. et al. Condensation of excitons in a trap. Nano Lett. 12, 2605 (2012).

High, A. A. et al. Spontaneous Coherence in a Cold Exciton Gas. Nature 483, 584 (2012).

Cristofolini, P. et al. Coupling quantum tunneling with cavity photons. Science 336, 704 (2012).

Timofeev, V. B. & Gorbunov, A. V. Bose-Esintein condensation of dipolar excitons in double and single quantum wells. Phys. Stat. Sol. C 5, 2379 (2008).

Schinner, G. J. et al. Many-body correlations of electrostatically trapped dipolar excitons. arXiv:1111.7175. (2011)

Alloing, M., Fuster, D., Gonzalez, Y., Gonzalez, L. & Dubin, F. Observation of macroscopic coherence of self-organised dipolar excitons. arXiv:1210.3176. (2012).

Blatt, J. M., Ber, K. W. & Brandt, W. Bose-Einstein condensation of excitons. Phys. Rev. 126, 1691 (1962)

Keldysh, L. V. & Kopaev, Y. V. Possible instability of the semimetallic state toward Coulomb interaction. Sov. Phys. Solid State 6, 2219 (1965).

Keldysh, L. V. & Kozlov, A. N. Collective properties of excitons in semiconductors. Sov. Phys. JETP 27, 521 (1968).

Butov, L. V., Lai, C. W., Ivanov, A. L., Gossard, A. C. & Chemla, D. S. Towards Bose-Einstein condensation of excitons in potential traps. Nature 47, 417 (2002).

Hammack, A. T. et al. Trapping of cold excitons in quantum well structures with laser light. Phys. Rev. Lett. 96, 227402 (2006).

Combescot, M., Moore, M. G. & Piermarocchi, C. Optical traps for dark excitons. Phys. Rev. Lett. 106, 206404 (2011).

Gorbunov, A. V., Timofeev, V. B. & Demin, D. A. Electro-optical trap for dipolar excitons in a GaAs/AlAs Schottky diode with a single quantum well. JETP Letters 94, 800 (2011)

Negoita, V., Snoke, D. W. & Eberl, K. Huge density-dependent blueshift of indirect excitons in biased coupled quantum wells. Phys. Rev. B 61, 2779 (2000).

Christianen, P. C. M., Piazza, F., Lok, J. G. S., Maan, J. C. & van der Vleuten, W. Magnetic trap for excitons. Physica B 249, 624 (1998).

Kowalik-Seidl, K. et al. Forming and confining of dipolar excitons by quantizing magnetic fields. Phys. Rev. B 83, 081307(R) (2011).

Chen, G. et al. Artificial trapping of a stable high-density dipolar exciton fluid. Phys. Rev. B 74, 045309 (2006).

High, A. A. et al. Indirect excitons in elevated traps. Nano Lett. 9, 2094 (2009).

High, A. A. et al. Trapping indirect excitons in a GaAs quantum-well structure with a diamond-shaped electrostatic trap. Phys. Rev. Lett. 103, 087403 (2009).

Winbow, A. G. et al. Electrostatic Conveyer for Excitons. Phys. Rev. Lett. 106, 196806 (2011).

Kowalik-Seidl, K. et al. Tunable photoemission from an excitonic antitrap. Nano Lett. 12, 326 (2012).

Butov, L. V. et al. Formation mechanism and low-temperature instability of exciton rings. Phys. Rev. Lett 92, 117404 (2004).

Rapaport, R. et al. Charge separation of dense two-dimensional electron-hole gases: mechanism for exciton ring pattern formation. Phys. Rev. Lett 92, 117405 (2004).

Alloing, M., Lemaitre, A., Galopin, E. & Dubin, F. Nonlinear dynamics and inner-ring photoluminescence pattern of indirect excitons. Phys. Rev. B 85, 245106 (2012).

Bosio, C., Staehli, J. L., Guzzi, M., Burri, G. & Logan, R. A. Direct-energy-gap dependence on Al concentration in AlxGa1-xAs. Phys. Rev. B 38, 3263 (1988).

Monemar, B., Shih, K. K. & Pettit, G. D. Some optical properties of the AlxGa1xAs alloys system. J. Appl. Phys. 47, 2604 (1976).

Tersoff, J. Theory of semiconductor heterojunctions: The role of quantum dipoles. Phys. Rev. B 30, 4874(R) (1984).

Ivanov, A. L. Thermalization and photoluminescence dynamics of indirect excitons at low bath temperature. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 16, S3639 (2004).

Hammack, A. T. et al. Kinetics of the inner ring in the exciton emission pattern in GaAs coupled quantum wells. Phys. Rev. B 80, 155331 (2009).

Alloing, M., Lemaitre, A. & Dubin, F. Quantum signature blurred by disorder in indirect exciton gases. EuroPhys. Lett. 93, 17007 (2011).

Ivanov, A. L. et al. Origin of the inner ring in photoluminescence patterns of quantum well excitons. Europhys. Lett. 73, 920 (2006).

Kuznetsova, Y. Y. et al. Excitation energy dependence of the exciton inner ring. Phys. Rev. B 85, 165452 (2012).

Remeika, M. et al. Localization-delocalization transition of indirect excitons in lateral electrostatic lattices. Phys. Rev. Lett. 102, 186803 (2009).

Manek, I., Ovchinnikov, Y. B. & Grimm, R. Generation of a hollow laser beam for atom trapping using an axicon. Optics. Comm. 147, 67 (1998).

Schindler, P. & Zimmermann, R. Analysis of the exciton-exciton interaction in semiconductor quantum wells. Phys. Rev. B 78, 045313 (2008).

Laikhtman, B. & Rapaport, R. Exciton correlations in coupled quantum wells and their luminescence blue shift. Phys. Rev. B 80, 195313 (2009).

Snoke, D. W., Liu, Y., Denev, D., Pfeiffer, L. & West, K. Luminescence rings in quantum well structures. Solid. State Commun. 127, 187 (2003).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported financially by the EU ITN-INDEX, by the spanish MEC (QOIT, TOQATA) and by the ERC AdG QUAGATUA. F.D. also acknowledges the Ramon y Cajal program. Furthermore, M.A. and F.D. are grateful to M. Lewenstein and J. Eschner for their support.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed equally to this work.

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Alloing, M., Lemaître, A., Galopin, E. et al. Optically programmable excitonic traps. Sci Rep 3, 1578 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep01578

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/srep01578

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.