Key Points

-

The General Dental Practice may be a good place to screen patients for type 2 diabetes, using a brief self-report method or an instant HbA1c test.

-

Patients find such screening in such a setting acceptable

-

Offering patients a self-report and HbA1c test makes it 3 times more likely that they will respond to the test and seek a diagnostic test, than if they were offered a single self-report screening test alone.

Abstract

Aim The objective of this study was to determine dental patients' uptake of two preliminary screening tools for risk of diabetes (the Finnish Diabetes Risk Score –FINDRISC- and HbA1c finger-prick testing) in general dental practice, and to determine the number of patients at risk of type 2 diabetes (T2D) based on the results of these screening tests.

Methods Patients aged 45 and over, who did not already have a diagnosis of diabetes, visiting primary dental practitioners for routine appointments in London (N = 244) and Staffordshire (N = 276), were offered the chance to be screened for diabetes risk using the FINDRISC a self-report screening tool to assess risk of development of diabetes in the next ten years. If a patient's score showed them to be at risk, they were offered an instant HbA1c finger-prick test to further screen for possible type 2 diabetes, where they were given their result instantaneously. Patients found to be at risk on either screening test, were referred to their GP for formal diagnostic testing.

Results A total of 1,035 patients eligible for inclusion were asked to take part. Five hundred and twenty patients consented to screening. Of these, 258 patients (49.6%) were found to be at risk of developing diabetes based on FINDRISC scores and were referred to the GP for further testing and offered a further screening finger-prick blood test at the dental practice. A total of 242 (93.8% of those offered the test) accepted the on the spot finger-prick test. On this A1c test, had a result of 5.7% or higher, indicating increased risk for diabetes. Of the 258 who were referred to their GP for formal diabetes testing, 155 (60%) contacted their doctor. There was a significant association between the number of 'at risk' screening results a person received and whether or not a patient contacted their GP (P <0.0001). The odds of patients contacting the GP was 3.22 times higher if they were referred with two positive diabetes risk results (positive FINDRISC, positive HbA1c) rather than just one (positive FINDRISC, negative HbA1c).

Conclusions The study demonstrates a two-step method of diabetes screening that appears to be acceptable by dental patients, a sizeable proportion of whom were identified as at risk of developing diabetes, and the majority following the recommendation for further testing with their GP. While the majority followed the recommendation for further testing with their GP, patients were three times more likely to contact their GP if they received a positive risk result on both screening tools.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Diabetes is an illness characterised by chronically elevated levels of blood glucose concentration, a condition known as hyperglycaemia, for which there is no known cure. Type 2 diabetes (T2D) has become a huge burden for the adult population with ever-increasing prevalence,1 however, there is no screening programme policy in place in the UK despite the fact that detecting diabetes early on is key to health outcomes.2

Screening for diabetes can potentially allow for early diagnosis and treatment, which can prevent diabetes-related complications.3 Although screening for disease can sometimes have adverse effects on an individual, screening for diabetes has been shown not to have any long-term adverse effects.4 Therefore, it is suggested that screening for diabetes is essential to identify diabetes and importantly, its precursors, earlier and more efficiently.

Diabetes can be screened for using a variety of methods, in addition to traditional diabetes screening methods such as the oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT) where patients are required to consume glucose and then have blood samples taken afterward to determine how quickly the glucose is cleared from the blood; the use of HbA1c as a measure of glycaemic control over the past 12 weeks, has also been recommended as a viable means of diagnosing diabetes.5 An invasive test, as it requires a blood sample, HbA1c testing does not require fasting or restriction to certain times of the day to be measured, so in many respects it is easier to carry out than an OGTT. Furthermore, while traditionally HbA1c tests require laboratory facilities to take place, the recent introduction of point of care measurement through finger prick devices has made the measurement of A1c more accessible.6,7 As an alternative to a blood test, the FINDRISC is a non-invasive screening tool that provides a measure of the probability of developing type 2 diabetes over the next ten years.8 It is a brief questionnaire consisting of eight questions about variables correlated with the risk of developing diabetes: age; body mass index; family history of diabetes; waist circumference; use of anti-hypertensive medication; history of elevated blood glucose; meeting the criterion for daily physical activity and daily consumption of fruit and vegetables. FINDRISC has been used successfully as a screening tool for diabetes9 and its reliability and validity have been clearly established.10,11

Screening for diabetes can be carried out in various health settings.12 As diabetes is recognised as a significant risk factor for serious, progressive periodontal disease13 and as periodontal disease may contribute to the progression of impaired glucose tolerance to diabetes,14 the dental setting seems like a plausible context for the identification of people at risk of diabetes.

Some recent research from the US has examined the usefulness of screening for diabetes in dental settings. Four US studies15,16,17,18 reliably supported the notion that screening for pre-diabetes and diabetes using a combination of invasive and/or self-report methods was feasible, acceptable to patients and the dental team and effective in US dental offices.

In the single UK study carried out in general dental practices in London using a self-report risk measure developed in the UK,19,20 it was found that notwithstanding the manpower challenges facing dental teams and the fairly low uptake of further screening by patients, the identification of diabetes in dental practices was possible. One explanation for the low uptake of further diagnostic testing in this study could be the fact that patients tend to judge the severity of the illness by cues such as the complexity of the diagnostic tool used, In the case of diabetes in particular, previous work (20) showed that diabetes patients used their diagnosis journey to judge how serious their diabetes was; the more complex the diagnosis, (where for for example, the diagnosis was made by a hospital consultant rather than a GP) the more serious patients thought their diabetes to be.

On the basis of these findings, we reasoned that supplementing a self-report diabetes risk assessment with a more invasive, instant HbA1c blood test might improve the uptake of further formal GP testing. At the same time, we wished to explore the acceptability of such a double-screening method in UK dental practices

Thus the objective of this study was to determine the uptake of diabetes screening in dental patients, using FINDRISC and HbA1c information as preliminary screening tools, and to determine the proportion of patients who attend their GP for further, formal diabetes diagnostic testing.

Methods

Participants meeting the inclusion criteria were recruited from two general dental practices in London and Staffordshire, UK. Dental patients who were aged 45 and over, could speak fluent English and had no diagnosis of diabetes or pre-diabetes were sent an invitation letter with information explaining the nature of the research. These inclusion criteria were set due to an increase in diabetes risk with age and because the risk questionnaire had been validated in English.

On arrival, participants wishing to take part met with the researcher, gave informed consent and completed a demographics and FINDRISC questionnaire. The participant then saw the dentist for their routine appointment. At the end of their appointment, the participant met with the researcher who gave the participant their result of the FINDRISC. Participants with a score of <10 on the FINDRISC were debriefed about their risk result, reassured and thanked for their participation. Patients with a score of ≥10 on the FINDRISC were told about their increased risk and offered an HbA1c finger-prick test to explore their risk further. Participants receiving the blood test were given the result instantaneously, with an explanation of its meaning. Regardless of whether they accepted taking the HbA1c test, or having taken it, the actual HbA1c reading, all patients with a FINDRISC of >10 were advised by the researcher to visit their GP for a formal diagnostic test via verbal advice and written information. All participants' GPs were informed of their participation through a standard letter from the dental practitioner and researcher, and a formal diagnostic test was recommended where results indicated the need for this. One month after participants took part in screening, they were contacted by telephone by the researcher to find out if they had been to their GP for formal diagnostic testing as recommended. If they had not already been, a second call was made one month later to find out the outcome. Finally, three months after the initial screening was conducted, patients' GPs were contacted through a standard letter and reply slip to find out if the patient had been in contact to further confirm the patient's self-report or to confirm the outcome for patients unable to be contacted.

Results

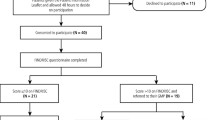

Figure 1 shows the flow of participants through the study. A total of 3,700 NHS and private patients had a dental appointment during the 118 day recruitment period. However, 2,109 patients were excluded as they were either under 45 years of age (N = 1,888), did not speak fluent English (N = 59), or already had diabetes/ pre-diabetes (N = 162). A further 556 potential participants were not asked to take part as they either did not attend their appointment (N = 121) or could not practically be tested by the single researcher (N = 435).

Of the remaining 1,035 patients, 520 (50.2%) consented to participate and completed the FINDRISC screening questionnaire. Five hundred and fifteen patients refused to participate in the study. The main reasons for refusal were, a recent blood glucose test, a recent health check-up such as the Well Man's Check arranged through the GP, dental pain and fear, and lack of interest in the research.

Two hundred and sixty-two (N = 262) participants scored below the cut off score of ten on the FINDRISC questionnaire, and therefore were not offered any further screening. Two hundred and fifty-eight patients were found to be at risk of developing diabetes based on the current recommended FINDRISC cut off score of ten, and so were offered the further screening test, and advised to visit their GP for formal diagnostic testing. The majority of participants (N = 247, 47.5% of those who took part) fell into the slightly elevated risk category, while 101 (19.42% of those who took part) fell in the low risk category and 172 (33%) were seen as having a moderate, high or very high risk of developing diabetes. Table 1 outlines the number of participants by risk score category on the risk questionnaire.

Of the 258 found to be at risk of developing diabetes on the FINDRISC, the majority (N = 242, 93.8%) accepted and received the further screening HbA1c test. These A1c test results are shown in Table 2 that follows.

On this A1c test, ten participants (4.13% of those who took the test) had a result of ≥6.5%, 108 participants (44.6% of those who took the test) had a result of between 5.7% and 6.4%, while 124 participants (51.24% of those who took the test) had a result of less than 5.7%.

Of the 258 participants who were advised to visit their GP for formal diabetes testing, N = 155 (60%) contacted their doctor regarding an appointment for further testing.

There was a significant association between the number of 'at risk' screening results a person received and whether or not a patient would follow recommendation and contact their GP (χ2 [1] = 16.84, P <0.0001). Furthermore, the number of positive risk scores significantly influenced GP contact; patients were more likely to contact their GP if they had received two positive risk scores. The odds ratio of patients contacting the GP was 3.22 times higher if they were referred with two positive risk results (both a positive FINDRISC and positive HbA1c risk result) as opposed to just one (a positive FINDRISC but negative HbA1c).

Discussion

The objective of this study was to determine the uptake of dental patients using FINDRISC and HbA1c information as preliminary screening tools in screening for possible diabetes, and determine the number of patients at risk of diabetes.

As with the previous US and UK studies, the current study found that many dental patients were happy to participate and receive one or more diabetes screening tests offered to them. The results showed a successful uptake of dental patients for diabetes screening, with 50% of eligible patients consenting to participate. The refusal rate of 515 was higher than the figure stated in a previous study by D. Wright et al.19 Several reasons for this can be offered, such as, that potential participants are much more likely to take part in research that is concerned with an issue which is particularly relevant to the participants' lives; overall there is a decline in willingness to participate in scientific studies in Western countries, which may hold little immediate benefit to the participant.21 Finally, participants may be wary of committing their involvement to research that is likely to take up a substantial amount of their time, given how scientific research has become increasingly demanding over the last decade.21

Almost half of dental patients screened using the FINDRISC were found to be at risk of developing diabetes based on the current cut-offs. In line with previous work, the majority of participants fell into the slightly elevated risk category, with a personalised risk score of between 7 and 11.22 Wright and colleagues19 found that 84% of dental patients screened had at least some increased level of risk of diabetes, based on the NICE guidance tool which included a risk questionnaire and BMI measurement. Our sample, based on the risk questionnaire alone showed a similar result; that 419 (81%) of the 520 participants had some level of elevated risk of diabetes. When looking at the results of the point of care HbA1c measure, 118 (45% of those taking the test) had a score of ≥5.7% suggesting a risk of pre-diabetes and diabetes.23 Compared to 30% found by Herman and colleagues18 and 40% in the participant sample of Genco and colleagues,15 our result is slightly higher, probably because only those with a FINDRISC score over ten were offered the HbA1c test. The majority of participants (94%) scoring ten or higher on the FINDRISC were happy to have their HbA1c measured by the researcher. Therefore, these results support the notion that dental patients are happy to be screened for diabetes using a combination of a simple questionnaire and a more invasive finger-prick blood test.

Crucially, a high proportion (60%) of those advised to visit their GP for further formal diabetes testing followed this advice and contacted their GP. This is a much more promising result than found previously. For instance, Wright and colleagues reported that only 20% of patients identified as at risk of developing diabetes attended their GP.19 Genco and colleagues reported that 35% attended their GP for follow up;15 though there was a significant difference in follow-up rates between patients referred from a community health centre, where over 78% attended their GP, compared to only 21% from private dental offices.

There are of course limitations to this study that should be considered. There was a discrepancy in the numbers of patients who were eligible to participate and those who took part, not only because there were patients who refused to participate, but because the method of data collection meant that some patients who were eligible to participate were missed because the researcher was not able to approach every potential participant before their appointment with the dentist. Therefore, the number of dental patients who would have participated might be different in a study using more than one researcher recruiting and testing at any one time. This also has implications for the adoption of diabetes screening in the dental practice. Recruitment and screening in the current study was carried out by a psychology researcher and as such, the manpower and time issues that were raised in the Wright et al. study19 still need to be considered before these findings are taken to routine dental care.

HbA1c was only measured in those participants who scored highly enough on the FINDRISC questionnaire to qualify for the further screening test. As the risk questionnaire is mainly self-report, there is always a chance that those participating may exaggerate their answers and therefore the questionnaire may not give a true representation of a person's risk. Thus, those in our sample who did not score highly enough on the FINDRISC to qualify for the second screening test; the HbA1c test, may well have had an elevated HbA1c score, therefore increasing the percentage of overall participants with a high risk HbA1c score of ≥5.7%.

Finally, although the study was carried out in a dental setting, all screening took place by a trained researcher rather than the dental team and to this end the practicalities of incorporating this screening into routine practice have not been investigated.

Conclusion

This study demonstrates a method of diabetes screening that shows an acceptable rate of uptake by dental patients. It demonstrates a relatively high number of patients 'at risk' of developing diabetes and that the majority of these follow up their screening result with further tests with their GP.

References

Wild S, Roglic G, Green A, Sicree R, King H . Global prevalence of diabetes: estimates for the year 2000 and projections for 2030. Diabetes Care 2004; 27: 1047–1053.

Harris M I, Eastman R C . Early detection of undiagnosed diabetes mellitus: a US perspective. Diabetes Metab Res Rev 2000; 16: 230–236.

Marre M, Travert F . Diabetes: early screening costs and benefits. In Barnett AH (ed). Clinical Challenges In Diabetes. Oxford: Atlas Medical Publishing, 2010.

Adriaanse M C, Snoek F J, Dekker J M et al. No substantial psychological impact of the diagnosis of Type 2 diabetes following targeted population screening: The Hoorn Screening Study. Diabet Med 2004; 21: 992–998.

Saudek C D, Herman W H, Sacks D B, Bergenstal R M, Edelman D, Davidson MB . A new look at screening and diagnosing diabetes mellitus. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2008; 93: 2447–2453.

Wensil A M, Smith J D, Pound M W, Herring C . Comparing pointofcare A1C and random plasma glucose for screening diabetes in migrant farm workers. J Am Pharm Assoc 2013; 53: 261–266.

Sicard D A, Taylor J R . Comparison of pointofcare HbA1c test versus standardized laboratory testing. Ann Pharmacother 2005; 39: 1024–1028.

Lindstrom J, Louheranta A, Mannelin M et al. The Finnish Diabetes Prevention Study (DPS): Lifestyle intervention and 3year results on diet and physical activity. Diabetes Care 2003; 26: 3, 230–236.

Tankova T, Chakarova N, Atanassova I, Dakovska L . Evaluation of the Finnish Diabetes Risk Score as a screening tool for impaired fasting glucose, impaired glucose tolerance and undetected diabetes. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 2011; 92: 46–52.

Janghorbani M, Adineh H, Amini M . Evaluation of the Finnish Diabetes Risk Score (FINDRISC) as a screening tool for the metabolic syndrome. Rev Diabet Stud 2013; 10: 283–292.

Gomez-Arbelaez D, Alvarado-Jurado L, Ayala-Castillo M, Forero-Naranjo L, Camacho P A, Lopez-Jaramillo P. Evaluation of the Finnish Diabetes Risk Score to predict type 2 diabetes mellitus in a Colombian population: A longitudinal observational study. World J Diabetes 2015; 6: 1337–1344.

Howse J H, Jones S, Hungin A P . Screening for diabetes in unconventional locations: resource implications and economics of screening in optometry practices. Health Policy 2011; 102: 193–199.

Southerland J H, Taylor G W, Offenbacher S . Diabetes and periodontal infection: Making the connection. Clin Diabetes 2005; 23: 171–178.

Pontes Andersen C C, Flyvbjerg A, Buschard K, Holmstrup P . Periodontitis is associated with aggravation of prediabetes in Zucker fatty rats. J Periodontol 2007; 78: 559–565.

Genco R J, Schifferle R E, Dunford R G, Falkner K L, Hsu W C, Balukjian J . Screening for diabetes mellitus in dental practices: a field trial. J Am Dent Assoc 2014; 145: 57–64.

Greenberg B L, Thomas P A, Glick M, Kantor M L . Physicians' attitudes toward medical screening in a dental setting. J Public Health Dent 2015; 75: 225–233.

Bossart M, Calley K H, Gurenlian J R, Mason B, Ferguson R E, Peterson T . A pilot study of an HbA1c chairside screening protocol for diabetes in patients with chronic periodontitis: the dental hygienist's role. Int J Dent Hyg 2016; 14: 98–107.

Herman W H, Taylor G W, Jacobson J J, Burke R, Brown M B . Screening for prediabetes and type 2 diabetes in dental offices. J Public Health Dent 2015; 75: 175–182.

Wright D, Muirhead V, Weston-Price S, Fortune F . Type 2 diabetes risk screening in dental practice settings: a pilot study. Br Dent J 2014; 216: E15.

Parry O, Peel E, Douglas M, Lawton J . Issues of cause and control in patient accounts of Type 2 diabetes. Health Educ Res 2006; 21: 97–107.

Galea S, Tracy M . Participation rates in epidemiologic studies. Ann Epidemiol 2007; 17: 643–653.

Costa B, Barrio F, Pinol J L et al. Shifting from glucose diagnosis to the new HbA1c diagnosis reduces the capability of the Finnish Diabetes Risk Score (FINDRISC) to screen for glucose abnormalities within a real-life primary healthcare preventive strategy. BMC Med 2013; 11: 45.

Silverman R A, Thakker U, Ellman T et al. Haemoglobin A1c as a screen for previously undiagnosed prediabetes and diabetes in an acute-care setting. Diabetes Care 2011; 34: 1908–1912.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Refereed Paper

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Bould, K., Scott, S., Dunne, S. et al. Uptake of screening for type 2 diabetes risk in general dental practice; an exploratory study. Br Dent J 222, 293–296 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.2017.174

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.2017.174

This article is cited by

-

Opportunistic health screening for cardiovascular and diabetes risk factors in primary care dental practices: experiences from a service evaluation and a call to action

British Dental Journal (2023)

-

A systematic review of diabetes risk assessment tools in sub-Saharan Africa

International Journal of Diabetes in Developing Countries (2022)

-

The prevalence of potentially undiagnosed type II diabetes in patients with chronic periodontitis attending a general dental practice in London - a feasibility study

British Dental Journal (2021)

-

Patient acceptability of targeted risk-based detection of non-communicable diseases in a dental and pharmacy setting

BMC Public Health (2020)

-

The Role of the Oral Healthcare Team in Identification of Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus: A Systematic Review

Current Oral Health Reports (2020)