Key Points

-

Improves dental practitioners' understanding of systemic sclerosis.

-

Improves recognition of key orofacial manifestations of systemic sclerosis.

-

Highlights difficulties faced by patients with regards to oral hygiene measures and access to routine treatment.

Abstract

Systemic sclerosis (SSc) is a multisystem disease of unknown aetiology characterised by microangiopathy, dysregulated immune function and tissue remodelling, which commonly involves the oral cavity. Orofacial manifestations of SSc contribute greatly to overall disease burden and yet are regularly overlooked and under-treated. This may reflect a pre-occupation amongst rheumatology clinicians on potentially life-threatening internal organ involvement, but is also a consequence of insufficient engagement between rheumatologists and dental professionals. A high proportion of SSc patients report difficulty accessing a dentist with knowledge of the disease and there is recognition amongst dentists that this could impact negatively on patient care. This review shall describe the clinical features and burden of orofacial manifestations of SSc and the management of such problems. The case is made for greater collaborative working between rheumatologists and dental professionals with an interest in SSc in both the research and clinical setting.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Systemic sclerosis (SSc) is a multisystem disease of unknown aetiology characterised by microangiopathy, dysregulated immune function and tissue remodelling. Evidence of each of these three heavily inter-dependent pathological hallmarks can be identified within the diverse anatomical tissues that comprise the oral cavity; the accessibility of which makes this area an attractive site to study the pathogenesis of this heterogeneous and poorly understood disease. Moreover, orofacial manifestations of SSc are common, contributing greatly to overall disease burden and yet are regularly overlooked and potentially under-treated. This perhaps reflects a pre-occupation amongst treating clinicians on potentially life-threatening internal organ involvement, but is also a consequence of insufficient engagement between rheumatologists and dental professionals. Surveys have identified a high proportion of SSc patients who have had difficulty accessing a dentist with knowledge of the disease and there is recognition amongst dentists that this could impact negatively on patient care.1 This review shall describe the clinical features and burden of orofacial manifestations of SSc, the methods available to assess oral pathology and a practical approach to managing such problems.

Background and clinical features

SSc is rare with an estimated prevalence of approximately 250 per million and an annual incidence of 26/million/person years2 with a strong propensity for women (7:1).3 Previously, clinical descriptions of SSc focused heavily on the presence of excessive cutaneous fibrosis - hence the synonym, scleroderma. However, it was gradually acknowledged that a combination of vasculopathy, fibrotic disease, and dysregulated immune function were responsible for pathology in a number of internal organs including the heart, lungs and gastrointestinal (GI) tract (Table 1).4

Fibrosis

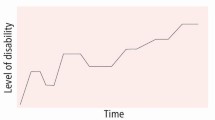

Classification of SSc according to the extent of cutaneous fibrosis was proposed in the 1980s owing to its value in predicting internal organ involvement and survival, with two main types described: diffuse cutaneous SSc (dcSSc) and limited cutaneous SSc (lcSSc).5 Diffuse cutaneous SSc with skin thickening affecting proximal regions such as the upper arms, thighs and trunk, generally predicts a more 'fibrotic' phenotype with significant morbidity and mortality secondary to fibrosis and loss of internal organ function. Meanwhile, lcSSc involves skin changes restricted to the face, distal arms and feet, and predicts a more 'vascular' phenotype with lower morbidity and mortality.

Dysregulated immune function

Altered vascular permeability and extravasation of leukocytes is thought to represent a key driver of tissue remodelling, resulting in inflammatory conditions such as arthritis and myositis. An early clinical presentation of this disease process is the appearance of puffy fingers. Immunosuppression remains the mainstay of treatments to arrest the progression of organ fibrosis.

Microvascular angiopathy

Endothelial injury at the microvascular level is considered an important early pathological driver.6 Episodic vasoconstriction of the digital microvasculature in response to cold exposure or emotional stress (Raynaud's phenomenon [RP]) is typically the earliest manifestation of the disease. In addition to functional vascular disturbance, structural microvascular abnormalities occur in SSc including disorganised neoangiogenesis and capillary loss; both of which can be directly visualised using nail-fold capillaroscopy which is an important diagnostic tool.7 This microangiopathy can result in significant tissue hypoxia that threatens tissue viability leading to digital ulceration and occasionally gangrene. Microvascular injury occurs in other vascular beds and can result in potentially life-threatening organ manifestations such as scleroderma renal crisis and pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH). Increased vascular permeability, tissue hypoxia and oxidative stress are thought to contribute to the excessive collagen synthesis and fibrosis.

The gastrointestinal tract in SSc

Gastrointestinal (GI) tract manifestations are a major cause of morbidity in SSc but have not attracted the same attention to therapeutics as manifestations of the skin, lung and kidneys perhaps owing to the limited contribution to mortality and the unique challenges associated with evaluating the GI tract. The GI tract has three major functions: digestion, the excretion of waste products, and the transit of food and waste. The architecture of the GI tract wall constantly evolves throughout its course to achieve these goals and each segment can be affected in SSc. There is a high burden of GI symptoms in SSc with cross-sectional studies identifying GI symptoms in more than 90% of patients with approximately 10% of patients experiencing symptoms on a daily basis.8

Motility is achieved by smooth muscle within the GI tract wall, as well as striated muscle in the oropharynx. A combination of neural dysfunction and fibrotic replacement of muscle significantly impairs GI motility, resulting in dysphagia, gastro-oesophageal reflux and gastroparesis within the proximal GI tract. Mucosal abnormalities and bacterial overgrowth within the distal GI tract may affect its absorptive capacity, leading to malnourishment, weight loss, and deficiencies of important vitamins and minerals. Mucosal vascular malformations such as gastric antral vascular ectasia (GAVE) in the stomach wall, can occur leading to potentially life-threatening haemorrhage or chronic iron deficiency.9

Clinical orofacial features

Similar to GI manifestations, there is a very high prevalence of abnormalities of the oral cavity and surrounding tissues with one or more features evident in virtually all patients with SSc (Table 2). Reports of oral manifestations predate recognition of a number of major organ manifestations of SSc such as PAH.10 Patients with early or limited forms of SSc may present to their dentist with detectable clinical features before a formal diagnosis has been established. Dentists are encouraged to enquire about symptoms of RP and changes in the quality of their skin elsewhere should they identify one or more of the following features in the correct clinical context.

Orofacial fibrosis and microstomia

Cutaneous involvement of the orofacial region causes reduction of the oral aperture, with the characteristic circumoral furrows or perioral 'whistle lines' seen in approximately 70% of patients (Figs 1 and 2), as well as a 'wide-eyed' appearance caused by periorbital fibrosis.11 Mouth opening can be impaired by tissue remodelling of the TMJ capsule12 demonstrated by a significantly reduced mean interincisal distance compared with the general population.13 Microstomia complicates maintenance of oral hygiene, dental treatment and prosthetic rehabilitation, and can also lead to difficulty with mastication and deglutition.12 Reduced lip and facial strength may cause difficulty with speech, facial expressions and saliva control. Fibrosis of the lingual fraenum (Fig. 3) has the potential to affect speech, saliva control and bolus manipulation.14,15

A large patient survey examining features of SSc which cause greatest aesthetic concern, found that the presence of circumoral furrows (80%), tighter mouth (77%), thin lips (73%) and loss of facial lines (68%) all featured most prominently, and were significantly more common than non-facial SSc appearances.16 From an aesthetic perspective, attempts have been made to manage circumoral furrowing using pulsed CO2 laser treatment.17 The use of dermal fillers and botulinum injections are also sometimes used with good results but have not been reported.

Functionally, daily exercises that aim to stretch the tissues of the face and neck have been shown to be effective in improving mouth opening but long-term outcomes are influenced by low exercise continuation rate, with secondary loss of efficacy linked with deterioration in compliance.12,18,19,20,21 A number of 'microstomia orthoses' have been developed and tested for a number of indications including post-radiotherapy22 and burns23,24,25,26,27 but such devices have not been as extensively investigated in SSc.28 Other non-surgical approaches have been described for microstomia including intense pulsed light therapy but require further study.29 Successful surgical interventions to increase the oral aperture such as commissuroplasty and autologous fat grafting have also been reported in SSc, and should be reserved for the more severe cases.30,31

Telangiectasia

Telangiectasiae are cuttaneous vascular malformations that are commonly found in SSc and are thought to occur secondary to disordered neoangiogenesis in ischaemic tissue.32 Telangiectasiae mostly develop in exposed cutaneous regions of the hands and face which has marked aesthetic implications, and can also be found on oral mucosal surfaces, typically the labial mucosa (Fig. 4). Telangiectasia may bleed following trauma but generally do not present a significant clinical risk when found intra-orally. Many patients consider them unsightly and efforts can be made to conceal extra-oral telangiectases using camouflage creams and make-up. Light-based treatments such as pulsed dye laser and intense pulsed light have been shown to have short term efficacy in SSc but long-term recurrence rates are not known.33

Oral mucosal atrophy and ulceration

Atrophy and ulceration of the oral mucosa can occur in SSc secondary to poor nutritional intake and vitamin deficiencies.12 Oral ulceration may also be an adverse consequence of the pharmacological management of SSc, involving methotrexate, azathioprine and cyclophosphamide.34 Management will involve correction of any nutritional deficiencies, topical treatment of the ulcers such as covering agents, and substitution of immunosuppressant medication as required. Persistent, non-healing ulcers should still be managed with caution, and biopsy may be indicated to rule out more sinister pathology.

Xerostomia

Xerostomia is reported in approximately two thirds of SSc patients and the impact is considered moderate to severe in over half of these patients.35,36,37 Studies involving minor salivary gland biopsies indicate that xerostomia may occur by two distinct mechanisms: immune-mediated destruction of the acinar tissues (as is typically found in Sjögren's syndrome), or fibrosis of the salivary glands themselves reducing their exocrine capacity.36,38,39,40 The presence of Sjögren's syndrome in patients with SSc appears to have a greater association with the lcSSc phenotype.36,39

Initial management should include specific advice on maintaining adequate oral hydration, minimising the frequency of sugar-containing food and drink, and stimulating saliva flow with sugar-free gum.41 Patients should have appropriate dental recall intervals and be provided with appropriate preventative care such as topical fluoride application, appropriate fluoride toothpaste and mouthwash prescription. A large number of artificial saliva replacement products are available in gel, spray, and pastille preparations, and can be helpful in patients with symptoms of xerostomia which are not managed effectively through routine advice. Referral to oral medicine departments might be necessary for those not responding to simple local measures. Pilocarpine hydrochloride may be prescribed in a hospital setting to stimulate saliva production but is only effective in those with some residual gland function.

Radiographic features

Periodontal ligament widening

Periodontal ligament (PDL) widening (Fig. 5) is a reported radiographic feature of SSc, but should be considered as an incidental finding rather than a diagnostic feature. Studies have reported the PDL width to be significantly increased, on average, in comparison to the general population, with posterior teeth affected to a greater degree.42,43,44,45 The precise cause and mechanisms of this PDL widening in the absence of an infective pathological cause have yet to be elucidated; however, it has been proposed that PDL volume is increased due to excessive collagen synthesis, as seen in other features of SSc.46

Mandibular resorption

Mandibular resorption has been reported in 10-33% of SSc patients and most commonly involves the angles of the mandible, followed by the condyle, coronoid process and the ascending ramus,47 with bilateral condylysis occurring in 13.7% of cases of resorption. Resorption of the zygomatic arch has also been reported.48 The underlying mechanisms are poorly understood but are thought to be primarily of vascular origin,12,47,49 and resorption patterns suggest sites of muscle insertions are particularly vulnerable to ischaemic injury of this nature.

Resorption may be visible on OPT radiographs (Fig. 6) and the degree and distribution of resorption can extend from minor blunting of the angles, to more pronounced concavity of the posterior ramus and eventually to more extensive resorption.11 Mandibular resorption can result in facial asymmetry, malocclusion, osteomyelitis and pathological fractures.50,51 Trigeminal neuralgia has been reported in SSc,52 with mandibular resorption proposed as a potential contributing factor in such cases.53 Resorption is usually managed conservatively, but total TMJ reconstruction has been used in the management of significant condylar resorption.12,54,55

Impact on dental and perio disease

Patients can be at greater risk of caries, periodontal conditions, and infections due to a number of factors including xerostomia, impaired oral hygiene practices and immunosuppressive drug use.13 Microvascular abnormalities within the gingival tissues have been observed, with a suggestion that the disease process itself may be a contributory factor in the emergence of periodontal disease.56 Gingival biopsies have identified higher levels of inflammatory infiltrate and lower expression of vascular endothelial growth factors in SSc compared with healthy controls.57 In addition, patients who are prescribed calcium channel blockers for Raynaud's phenomenon or ciclosporin as a part of immunosuppressant therapy may experience gingival overgrowth as a side-effect.58

Oral hygiene maintenance can be physically challenging for patients with SSc due to microstomia and reduced manual dexterity (Fig. 7), each of which can compromise the ability to use toothbrushes and inter-dental cleaning aids. Digital cutaneous fibrosis and ulceration, as well as ectopic calcinosis can significantly affect dexterity. Poor oral hygiene has been found to be closely associated with a reduced oral aperture, increased skin thickness, and reduced hand dexterity and finger flexion.59 Appropriate advice on the importance of maintaining oral hygiene should be provided to all patients with SSc and management of caries and periodontal disease does not differ from that of the general population. Other groups have demonstrated the value of a combined intervention program comprising orofacial exercises, education on oral hygiene techniques and adapted dental appliances on improving oral hygiene in SSc.60

Oral cancer

There has been a long-standing interest in the association between SSc and malignancy. A recent systematic review of cohort studies identified cancer as a contributing factor to mortality in up to 30% of patients.61 A recent large retrospective study identified a history of cancer in 7.1% of patients with SSc.62 The most commonly occurring cancers were breast (42.2%) followed by haematological (12.3%), gastrointestinal (11.0%) and gynaecological (11.0%) cancers.62 Oral and oropharyngeal cancers are not commonly associated with SSc,63 but some studies have shown an association.64,65,66

It has been reported that there is a greater risk of cancer within the first 12 months following SSc diagnosis,63 with 69% of cancers detected after SSc diagnosis.65 This is likely to be influenced by detection bias due to the closer monitoring and investigations following a diagnosis of SSc; however, it has been suggested that the disease process itself or the treatment of SSc (for example, immunosuppressant therapy) may be a role in cancer pathogenesis.65

Impact on quality of life

Overall oral health-related quality of life is significantly reduced in SSc compared with the general population, and independently associated with global health-related quality of life.13,67 The Mouth Handicap in Systemic Sclerosis (MHISS) has been developed to provide a disease-specific tool for evaluating mouth-related disability in SSc,68 and can be used to assess the patients concerns and the impact of SSc on day-to-day life.

Conclusions

Oral manifestations of SSc are common and often overlooked despite representing a significant cause of co-morbidity and reduced health-related quality of life in SSc. Dental professionals have the potential to identify some of the common early manifestations of this condition, which could result in earlier diagnosis. Appropriate education on orofacial exercises and oral hygiene can be delivered by dental professionals and may significantly lessen the burden of oral manifestations in SSc. Better collaboration between rheumatologists and the dental team is required to improve access to dental care and oral health outcomes for patients with SSc.

References

Leader D, Papas A, Finkelman M . A survey of dentists' knowledge and attitudes with respect to the treatment of scleroderma patients. J Clin Rheumatol. 2014; 20: 189–194.

Mayes M D, Lacey JV Jr, Beebe-Dimmer J et al. Prevalence, incidence, survival, and disease characteristics of systemic sclerosis in a large US population. Arthritis Rheum. 2003; 48: 2246–2255.

Nikpour M, Stevens W M, Herrick A L, Proudman S M . Epidemiology of systemic sclerosis. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2010; 24: 857–869.

D'Angelo W A, Fries J F, Masi A T, Shulman L E . Pathologic observations in systemic sclerosis (scleroderma). A study of fifty-eight autopsy cases and fifty-eight matched controls. Am J Med. 1969; 46: 428–440.

LeRoy E C, Black C, Fleischmajer R et al. Scleroderma (systemic sclerosis): classification, subsets and pathogenesis. J Rheumatol. 1988; 15: 202–205.

LeRoy EC . Systemic sclerosis. A vascular perspective. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 1996; 22: 675–694.

van den Hoogen F, Khanna D, Fransen J et al. 2013 classification criteria for systemic sclerosis: an American College of Rheumatology/European League against Rheumatism collaborative initiative. Arthritis Rheum. 2013; 65: 2737–2747.

Thoua N M, Bunce C, Brough G, Forbes A, Emmanuel A V, Denton C P . Assessment of gastrointestinal symptoms in patients with systemic sclerosis in a UK tertiary referral centre. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2010; 49: 1770–1775.

Duchini A, Sessoms S L . Gastrointestinal hemorrhage in patients with systemic sclerosis and CREST syndrome. Am J Gastroenterol. 1998; 93: 1453–1456.

Rosenthal I H . Generalized scleroderma; hidebound disease, its relation to the oral cavity, with case history and dental restoration. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1948; 1: 1019–1028.

Albilia J B, Lam D K, Blanas N, Clokie C M, Sandor G K . Small mouths. Big problems? A review of scleroderma and its oral health implications. J Can Dent Assoc. 2007; 73: 831–836.

Alantar A, Cabane J, Hachulla E et al. Recommendations for the care of oral involvement in patients with systemic sclerosis. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2011; 63: 1126–1133.

Baron M, Hudson M, Tatibouet S et al. The Canadian systemic sclerosis oral health study: orofacial manifestations and oral health-related quality of life in systemic sclerosis compared with the general population. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2014; 53: 1386–1394.

Vitali C, Baldanzi C, Polini F, Montesano A, Ammenti P, Cattaneo D . Instrumented Assessment of Oral Motor Function in Healthy Subjects and People with Systemic Sclerosis. Dysphagia 2015; 30: 286–295.

Frech T M, Pauling J D, Murtaugh M A, Kendall K, Domsic R T . Sublingual Abnormalities in Systemic Sclerosis. J Clin Rheumatol. 2016; 22: 19–21.

Paquette D L, Falanga V . Cutaneous concerns of scleroderma patients. J Dermatol 2003; 30: 438–443.

Apfelberg D B, Varga J, Greenbaum S S . Carbon dioxide laser resurfacing of peri-oral rhytids in scleroderma patients. Dermatol Surg. 1998; 24: 517–519.

Yuen H K, Marlow N M, Reed S G et al. Effect of orofacial exercises on oral aperture in adults with systemic sclerosis. Disabil Rehabil. 2012; 34: 84–89.

Pizzo G, Scardina G A, Messina P . Effects of a nonsurgical exercise program on the decreased mouth opening in patients with systemic scleroderma. Clin Oral Investig 2003; 7: 175–178.

Maddali Bongi S, Del Rosso A, Galluccio F et al. Efficacy of a tailored rehabilitation program for systemic sclerosis. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2009; 27(Suppl 54): 44–50.

Naylor W P, Douglass C W, Mix E . The nonsurgical treatment of microstomia in scleroderma: a pilot study. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1984; 57: 508–511.

Buchbinder D, Currivan R B, Kaplan A J, Urken M L . Mobilization regimens for the prevention of jaw hypomobility in the radiated patient: a comparison of three techniques. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 1993; 51: 863–867.

Conine T A, Carlow D L, Stevenson-Moore P . Dynamic orthoses for the management of microstomia. J Rehabil Res Dev. 1987; 24: 43–48.

Conine T A, Carlow D L, Stevenson-Moore P . The Vancouver microstomia orthosis. J Prosthet Dent. 1989; 61: 476–483.

Davis S, Thompson J G, Clark J, Kowal-Vern A, Latenser BA . A prototype for an economical vertical microstomia orthosis. J Burn Care Res 2006; 27: 352–356.

Dougherty M E, Warden GD . A thirty-year review of oral appliances used to manage microstomia, 1972 to 2002. J Burn Care Rehabil. 2003; 24: 418–431.

Ridgway C L, Warden G D . Evaluation of a vertical mouth stretching orthosis: two case reports. J Burn Care Rehabil. 1995; 16: 74–78.

Naylor W P, Manor R C . Fabrication of a flexible prosthesis for the edentulous scleroderma patient with microstomia. J Prosthet Dent 1983; 50: 536–538.

Comstedt L R, Svensson A, Troilius A . Improvement of microstomia in scleroderma after intense pulsed light: A case series of four patients. J Cosmet Laser Ther 2012; 14: 102–106.

Koymen R, Gulses A, Karacayli U, Aydintug Y S . Treatment of microstomia with commissuroplasties and semidynamic acrylic splints. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod 2009; 107: 503–507.

Del Papa N, Caviggioli F, Sambataro D et al. Autologous fat grafting in the treatment of fibrotic perioral changes in patients with systemic sclerosis. Cell Transplant. 2015; 24: 63–72.

Mould T L, Roberts-Thomson P J . Pathogenesis of telangiectasia in scleroderma. Asian Pac J Allergy Immunol. 2000; 18: 195–200.

Dinsdale G, Murray A, Moore T et al. A comparison of intense pulsed light and laser treatment of telangiectases in patients with systemic sclerosis: a within-subject randomized trial. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2014; 53: 1422–1430.

Porter S R, Leao J C . Review article: oral ulcers and its relevance to systemic disorders. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2005; 21: 295–306.

Bassel M, Hudson M, Taillefer S S, Schieir O, Baron M, Thombs B D . Frequency and impact of symptoms experienced by patients with systemic sclerosis: results from a Canadian National Survey. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2011; 50: 762–767.

Kobak S, Oksel F, Aksu K, Kabasakal Y . The frequency of sicca symptoms and Sjogren's syndrome in patients with systemic sclerosis. Int J Rheum Dis. 2013; 16: 88–92.

Swaminathan S, Goldblatt F, Dugar M, Gordon T P, Roberts-Thomson P J . Prevalence of sicca symptoms in a South Australian cohort with systemic sclerosis. Intern Med J. 2008; 38: 897–903.

Baron M, Hudson M, Tatibouet S et al. Relationship between disease characteristics and orofacial manifestations in systemic sclerosis: Canadian Systemic Sclerosis Oral Health Study III. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2015; 67: 681–690.

Avouac J, Sordet C, Depinay C et al. Systemic sclerosis-associated Sjogren's syndrome and relationship to the limited cutaneous subtype: results of a prospective study of sicca syndrome in 133 consecutive patients. Arthritis Rheum 2006; 54: 2243–2249.

Janin A, Gosselin B, Gosset D, Hatron P Y, Sauvezie B . Histological criteria of Sjogren's syndrome in scleroderma. Clin Exp Rheumatol 1989; 7: 167–169.

Montgomery-Cranny J, Hodgson T, Hegarty A M . Aetiology and management of xerostomia and salivary gland hypofunction. Br J Hosp Med (Lond) 2014; 75: 509–510: 11–4.

Marmary Y, Glaiss R, Pisanty S . Scleroderma: oral manifestations. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol 1981; 52: 32–37.

White S C, Frey N W, Blaschke D D et al. Oral radiographic changes in patients with progressive systemic sclerosis (scleroderma). J Am Dent Assoc 1977; 94: 1178–1182.

Alexandridis C, White S C . Periodontal ligament changes in patients with progressive systemic sclerosis. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol 1984; 58: 113–118.

Dagenais M, MacDonald D, Baron M et al. The Canadian Systemic Sclerosis Oral Health Study IV: oral radiographic manifestations in systemic sclerosis compared with the general population. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol 2015; 120: 104–111.

Mehra A . Periodontal space widening in patients with systemic sclerosis: a probable explanation. Dentomaxillofac Radiol 2008; 37: 183; author reply 184.

Haers P E, Sailer H F . Mandibular resorption due to systemic sclerosis. Case report of surgical correction of a secondary open bite deformity. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg 1995; 24: 261–267.

Hopper F E, Giles A D . Orofacial changes in systemic sclerosis-report of a case of resorption of mandibular angles and zygomatic arches. Br J Oral Surg 1982; 20: 129–134.

Ramon Y, Samra H, Oberman M . Mandibular condylosis and apertognathia as presenting symptoms in progressive systemic sclerosis (scleroderma). Pattern of mandibular bony lesions and atrophy of masticatory muscles in PSS, presumably caused by affected muscular arteries. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol 1987; 63: 269–274.

Seifert M H, Steigerwald J C, Cliff M M . Bone resorption of the mandible in progressive systemic sclerosis. Arthritis Rheum 1975; 18: 507–512.

Auluck A, Pai K M, Shetty C, Shenoi S D . Mandibular resorption in progressive systemic sclerosis: a report of three cases. Dentomaxillofac Radiol 2005; 34: 384–386.

Farrell D A, Medsger T A, Jr. Trigeminal neuropathy in progressive systemic sclerosis. Am J Med 1982; 73: 57–62.

Fischoff D K, Sirois D . Painful trigeminal neuropathy caused by severe mandibular resorption and nerve compression in a patient with systemic sclerosis: case report and literature review. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod 2000; 90: 456–459.

MacIntosh R B, Shivapuja P K, Naqvi R . Scleroderma and the temporomandibular joint: reconstruction in 2 variants. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2015; 73: 1199–1210.

Doucet J C, Morrison A D . Bilateral mandibular condylysis from systemic sclerosis: case report of surgical correction with bilateral total temporomandibular joint replacement. Craniomaxillofac Trauma Reconstr 2011; 4: 11–18.

Scardina G A, Pizzigatti M E, Messina P . Periodontal microcirculatory abnormalities in patients with systemic sclerosis. J Periodontol 2005; 76: 1991–1995.

Ozcelik O, Haytac M C, Ergin M, Antmen B, Seydaoglu G . The immunohistochemical analysis of vascular endothelial growth factors A and C and microvessel density in gingival tissues of systemic sclerosis patients: their possible effects on gingival inflammation. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod 2008; 105: 481–485.

Yuen H K, Weng Y, Reed S G, Summerlin L M, Silver R M . Factors associated with gingival inflammation among adults with systemic sclerosis. Int J Dent Hyg 2014; 12: 55–61.

Poole J L, Brewer C, Rossie K, Good C C, Conte C, Steen V . Factors related to oral hygiene in persons with scleroderma. Int J Dent Hyg 2005; 3: 13–17.

Poole J, Conte C, Brewer C et al. Oral hygiene in scleroderma: The effectiveness of a multi-disciplinary intervention program. Disabil Rehabil 2010; 32: 379–384.

Elhai M, Meune C, Avouac J, Kahan A, Allanore Y . Trends in mortality in patients with systemic sclerosis over 40 years: a systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2012; 51: 1017–1026.

Moinzadeh P, Fonseca C, Hellmich M et al. Association of anti-RNA polymerase III autoantibodies and cancer in scleroderma. Arthritis Res Ther 2014; 16: R53.

Onishi A, Sugiyama D, Kumagai S, Morinobu A . Cancer incidence in systemic sclerosis: meta-analysis of population-based cohort studies. Arthritis Rheum 2013; 65: 1913–1921.

Derk C T, Rasheed M, Spiegel J R, Jimenez S A . Increased incidence of carcinoma of the tongue in patients with systemic sclerosis. J Rheumatol 2005; 32: 637–641.

Derk C T, Rasheed M, Artlett C M, Jimenez SA . A cohort study of cancer incidence in systemic sclerosis. J Rheumatol 2006; 33: 1113–1116.

Kuo C F, Luo S F, Yu K H et al. Cancer risk among patients with systemic sclerosis: a nationwide population study in Taiwan. Scand J Rheumatol 2012; 41: 44–49.

Baron M, Hudson M, Tatibouet S et al. The Canadian systemic sclerosis oral health study II: the relationship between oral and global health-related quality of life in systemic sclerosis. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2015; 54: 692–696.

Mouthon L, Rannou F, Berezne A et al. Development and validation of a scale for mouth handicap in systemic sclerosis: the Mouth Handicap in Systemic Sclerosis scale. Ann Rheum Dis 2007; 66: 1651–1655.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Refereed Paper

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Veale, B., Jablonski, R., Frech, T. et al. Orofacial manifestations of systemic sclerosis. Br Dent J 221, 305–310 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.2016.678

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.2016.678

This article is cited by

-

Complete dentures: an update on clinical assessment and management: part 2

British Dental Journal (2018)

-

Oral health: OHRQoL in systemic sclerosis

British Dental Journal (2017)