Key Points

-

Improves the evidence base for the effectiveness of targeted service delivery to special care groups.

-

Provides information for other dental services to consider when developing and assessing special care services.

-

Describes how increasing accessibility of dental care to homeless people led to a decrease in the loss of clinical time due to failed or cancelled appointments.

Abstract

Objective The aim of this study was to describe the dental services delivered by the Community Dental Service (CDS) of Tower Hamlets (TH) and City and Hackney (CH) for adult homeless people in 2009-2011, to assess if the service met its planned objectives and to report the outcomes of the dental care provided.

Method TH and CH CDS provided a nine tier dental service for homeless people during April 2009 to September 2011, in which the dedicated mobile dental service (MDS) and the dedicated dental clinic (DDS) provided 3,102 dental appointments for homeless people. Data collection from a random sample (n = 350) of record cards of adult patients who were homeless and offered oral care from these services was conducted, in collaboration with an analysis of appointment books, service delivery rotas and day sheets. Patients' oral findings, treatments, challenges as well as feedback received from the service users were recorded and evaluated against the planned objectives.

Results One thousand two hundred and twelve (39.1%) of these appointments went to the 350 patients whose record cards were examined as part of this audit. One of the record cards randomly selected had incomplete date and was excluded from the results, so data was presented on the 349 complete record cards. The age range of these patients was 18-74 years, with a mean age of 38.46 years ± 9.1 standard deviation (SD) with 80% of the patients (n = 281) under 50 years of age. Forty percent of these patients presented in pain with a further 5% complaining of swelling and infection, 99% of people required treatment and only nine people had no decay, three of whom were edentulous. Two hundred and thirteen (61%) patients completed their treatments, which took between 1 to 18 appointments, but only 97 (27.8%) patients did so without any failed or cancelled appointments. Of the 128 (36.7%) patients who were lost after the first appointment, only 15 (11.7%) did not receive any treatment; most had been treated for pain with temporary fillings, extractions, permanent fillings and management of swelling. Sixty-seven band 1, 16 band 1.2 (emergency only), 148 band 2 and 52 band 3 courses of treatment were submitted.

Conclusion This study showed a significant need for services providing oral healthcare for this population and highlighted that flexibly delivered dental services, embedded in local health and social networks, seemed to promote uptake in these clients who normally find it extremely difficult to find dental care services elsewhere.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

An abundance of research indicates that homeless people have poor oral health1,2,3 and experience higher levels of dental caries and periodontal disease than the general population.4 Normative oral treatment needs are extensive with one study showing 76% of homeless people have a restorative need, 80% need oral hygiene measures and periodontal treatment and 38% have a prosthetic treatment need.5 Attending a dentist often takes low priority for homeless people; 54% of people asked in the Scottish smile4life report stated they had not visited the dentist for at least 10 years and 79% said they would like to drop in without an appointment for dental treatment.6 Over half of the sample (59%) stated that they would prefer to take painkillers than attend for dental treatment, 57% felt that the worst part of dental treatment was waiting and 48% found NHS dental treatment difficult to find. The oral health of this sample of homeless people was also poor. When compared with the Scottish section of the Adult Dental Health Survey 1998,7 this population of Scottish homeless people had fewer standing teeth, equivalent mean numbers of decayed and missing teeth but half the number of filled or restored teeth. The increased prevalence of decayed and missing teeth suggested that this population of homeless people attended for dental treatment only when experiencing pain.

Recommendations have been outlined for health services aimed specifically at homeless people, provided in a safe environment which is in effect a 'comfort zone', offering patients the opportunity to form trusting relationships with health professionals without barriers such as the fear of judgement or stigma, thus developing mutually trusting networks and building their own social capital.6 In 2004, the British Dental Association (BDA) policy document8 called for improvements in the delivery of dental care to homeless people. It recommended that the dental healthcare needs of homeless people could be addressed by a mixture of mainstream and dedicated provision that acknowledges the special needs of homeless people. The policy recommended there was a need for: flexibility in dental services (in terms of locations, opening hours etc); a combination of conventional location and outreach provision; an integrated, multidisciplinary service provision and coordinated case management to deal with the individual's needs; and clinicians with appropriate clinical expertise enabling homeless people, wherever possible, to use mainstream dental services.

The smile4life survey agreed that many homeless people find it difficult to access and afford dental care, necessitating a clear need for a comprehensive dental service for homeless people consisting of three 'tiers' of service:

-

1

Emergency dental services for those unable to take advantage of routine dental care

-

2

Ad hoc or one-off 'occasional' single-item treatments that can be accessed without the need to attend for a full course of treatment

-

3

Routine dental care/full course of treatment.

There are very few reports on the delivery of dental care to homeless people and their patterns of dental service use. Some anecdotal evidence suggests that homeless people are unreliable attendees and do not complete treatment, although 60% of attendees using a mobile dental service (MDS) in Glasgow were reported to attend for continuing care.8 Daly et al.9 provided a targeted dental service for homeless people offering a mixture of fixed site and outreach clinics. The fixed site clinic offered a full range of dental treatment and was located in an open access day centre catering for homeless people. This location facilitated dental attendees to access other social and housing services provided by the centre. The fixed site service was supplemented by outreach clinics within day centres and hostels across the boroughs. Daly concluded that the presence of the dental service promoted uptake of dental care but there was a trade-off between flexibility of attendance and efficient delivery of a treatment plan. Flexible attendance tended to result in multiple visits and delayed outcomes, which in themselves could have acted as barriers to care. The authors recommended that future research should explore the use of a mobile dental surgery (MDS) in promoting continuing care for homeless people.

It is also important to recognise that it is not just those sleeping rough who suffer from poor oral and dental health. People who have experienced homelessness living in temporary accommodation are also likely to experience the same problems that exacerbate oral disease and it is equally important that dental services are accessible for this group. It is particularly important to ensure that homeless families with children are able to access dental services, as oral and dental health problems in children can not only be traumatic and painful, but can also lead to continuing problems throughout adult life.10

Community dental services (CDS), the salaried dental service run by primary care trusts (PCTs), are the most likely source of dental care for homeless people.9 These services are designed to provide the full range of treatment to patient groups who may not otherwise seek treatment from general dental services (GDS) or those who have experienced difficulty in doing so. The CDS was previously free at the point of delivery, but since 2006, began charging under the NHS regulations. However, the available exemptions do not necessarily always apply to homeless people. For instance, although people who are on benefits are exempt from paying, some homeless people do not claim benefits, despite being entitled to them (due to their chaotic lifestyle, which is often compounded by substance misuse and mental health problems). Furthermore, homeless people may well not have the required evidence to prove an exemption; or they may not even know under which category of exemption to claim free NHS dental care. NHS dentists are advised not to refuse treatment to a patient on grounds of lack of evidence of exemption, but embarrassment about not having documentary evidence or about being unfamiliar with the categories of exemption may be an effective barrier to homeless people accessing dental care.8

It is not known how many homeless people there are in Tower Hamlets (TH) and City and Hackney (CH) but TH and CH together have the largest number of direct access (158 beds) and second stage supported housing (1,499 beds) for homeless people in London.11 The TH homeless strategy 2008-2013 reported that 1 in 12 children in TH live in homeless households.12 Statutory homeless acceptances have doubled to over 1,600 per annum in six years with eviction by family and friends representing 60% of all cases. This is mirrored by reported increases in the voluntary sector. Black and minority ethnic groups, nearly 49% of the population, are disproportionately affected by homelessness. Young people are also at increased risk. Over 2,000 single homeless people per year access the TH homeless services, with about 30% of people with some form of more complex need. Up to 1,000 people per year undergo transitions from the criminal justice system and return to the local area – many of whom have housing and support needs. Over the course of a year about 200 additional individuals 'sleeping rough' are contacted by outreach teams and the borough has one of the most significant street-based prostitution areas in London. The number of women presenting as homeless with needs relating to domestic violence is a key local concern. There has been a progressive increase in the use of temporary accommodation.12 The report concluded that increasing attention should be paid to the health impact of homelessness on groups in temporary accommodation and when contemplating the development of services, consideration must be given to the differing needs of groups within the homeless population, in particular women, ethnic minority groups, families and the young.

The CDS is commissioned by TH PCT but provides services across two of the three boroughs of East London – TH and CH. It provides dental care to people with special care needs and this includes people who are homeless. The vision of the CDS service is 'there is no patient we cannot reach'. The service recognises that a wide range of patients cannot get their needs met in general dental practice (GDP) – not necessarily because their clinical dental needs are more complex, but because they may not fit comfortably into the way GDS is organised. Such patients can be categorised as having 'special care needs' and the aim is to reach all of these patients if possible, by providing:

-

Maximum flexibility in the range of service models (services in clinics, MDS, a domiciliary team, sedation services and specialist clinical services so that few patients have to be referred to hospital)

-

Minimum barriers for patients in getting access to dental care – a 'special care help-line', patients able to self-refer as well as accepting referrals from family members and professionals

-

A commitment to working closely with local organisations that represent special care groups

-

A dedicated community dental outreach team (CDOT) [including link workers (LWs)] who proactively seek out disempowered groups, to work with their representatives and create bespoke models of services to meet their needs.

In line with this vision, the CDS provided a nine tier dental service delivery model for homeless people:

-

1

CDS planning with stakeholders. Collaborative working with statutory services, social services, housing services, children's services, drugs and alcohol action teams, charitable, religious, community organisations, other healthcare professionals and community organisations is essential to make services for homeless people successful. Services are planned to take into account the multiple needs of clients/patients such as substance misuse, domestic violence, street working and mental health issues. Some of the stakeholder organisations can be seen in Table 1

-

2

Integrated working with the dental public health team to ensure that information about services is available to all local health and social care services as well as community organisations. Integrating work with the team is also important to deliver training for carers and support workers and to develop new or improve existing services through patient and public engagement. Staff from both teams will often attend public health events together and will also mutually support outreach and engagement activities. The CDS also works closely with dental public health on research projects enabling the CDS to respond to new developments in public health thinking and to champion services for the homeless when engaging with dental commissioners where local service provision is being reviewed

-

3

Link worker (LW) outreach programmes, delivering access and information surgeries at various day centres and hostels, giving service users the opportunity and time to speak to someone face to face, ask questions about their own needs, arranging dental appointments, make referrals to the appropriate dental service, provide information on maintaining good oral health, inform service users of dental charges, help people complete HC113 forms and link service users to other health services – tobacco cessation team, TB unit, harm reduction teams. The LW should go to all new locations before a service is established, maintain regular contact with key organisations and client groups and return to the location once a service is completed to direct any remaining patients to nearby services or organise follow up care. In a 'homeless families' project, the LW will both complete preliminary work with the client group and during the treatment sessions will set up the 'stay and play dental inflatable chair' and engage with families. If the treating dentist adds fluoride prescriptions to their treatment plans, we send in the dental care professional with the same LW, to complete applications and also provide any treatment within their remit

-

4

Event participation – CDOT attends a wide spectrum of public health events maintaining the profile of the service and enabling new patients to be reached, such as the Crisis Summer Open Day, where treatments are also provided by voluntary clinical teams. Patients' further treatment needs are then provided by the CDS. The CDS also has a partnership commitment with Crisis providing MDS to the charity over the Christmas period and offering training for staff so that dental care can be provided to the homeless alongside all other health services provided at the Christmas shelters

-

5

Treatment in outreach settings using mobile/portable dental equipment to provide all ranges of oral care and dental treatment. The CDS has four 'pool' cars available and regularly provides four to eight sessions a day (20-40 a week) of domiciliary care to people who cannot access a dental surgery – this may be in residential homes, hospitals, people's own homes, hospices and day centres and includes hostels/drop-in-centres for people who are homeless. The facilities to provide treatment can range from a bedroom, an ordinary room set aside, to an equipped 'medical' room within, or attached to, a hostel or day centre. The service is organised so that anyone in pain and in need of urgent dental treatment will always be seen on the day

-

6

Treatment in a dedicated 'homeless' MDS at different locations in TH and CH, with 8-12 sessions being delivered weekly. The MDS rotate around locations (Table 1), all chosen in consultation with local stakeholders and continually reviewed for client uptake (Table 2). The provision of a MDS service involves careful planning and extensive risk assessments before the start of the programme. Potential problems need to be identified and organisations need to fully understand what is involved and thus make suggestions accordingly. Consideration is given to the noise pollution to local communities, obstruction to local traffic, safety, parking, access of staff to bathroom facilities etc. Planning involves organising the frequency of service, usually two sessions weekly on a fixed day; start times, which are often early to enable the homeless services to engage the 'breakfast crowd' and evening sessions in the summer; all services are essentially tailored to the needs of the users. Alternatively they may hold half-day sessions, sessions on alternate weeks, or a small short-term programme to bring people into care and then refer to a nearby CDS or GDP. The session format is often a combination of emergency appointments, drop-ins, check-up slots and treatment appointments. Anyone in pain and in need of urgent dental treatment will always be seen on the day. Information is given on the aims of the service, who can be seen, confidentiality, clinical records, data access, dental staff that will be present on the service, cancellation and failure to attend policies and the use of personal alarms. A request is made that the key workers inform dental staff if a service user is known to be, or potentially, prone to violence and aggressive behaviour. The organisations also provide information on fire drills, opening hours, busiest days, site managers, security, incident reporting, raising the alarm and key workers. For MDS services a box is provided for the reception area with all the information staff and service users will need to access dental care on the MDS or at one of the other dental clinics, as well as referral forms, team contact numbers and general information about oral health and accessing other services such as tobacco cessation. Posters and promotional material is distributed before a service starts, giving both practical information on access, opening times etc and oral health. A pilot programme may be introduced initially, by providing one or two sessions on site – offering a check-up and treatment on the same day and on a first come first services basis to ensure that there is a demand from the clients before a service is put in place

-

7

Treatment in a dedicated 'homeless' fixed site health centre with a dedicated dental service (DDS) – the dedicated primary-care clinic in TH is a multidisciplinary 'one-stop shop' – with general medical services, podiatry, dentistry, psychologist, health visitors, family planning and blood clinics, a BBV team, substance misuse clinics, mental health clinics and alcohol services etc, all delivered together at a single physical location. They only register people who are street homeless or those in temporary or hostel accommodation in the borough of TH and E1 and clients register with the practice rather than with a named doctor. This enables a case-based approach to be taken, with the physical health, mental health and substance misuse problems of each individual patient/client being dealt with in a coordinated way. The dental team includes four dentists and a dental care professional, offering approximately 16 available clinical sessions weekly, with a full range of NHS dental care. The service is in theory by appointment only, but in practice also operates on a 'walk-in' basis. Clients are often attracted by means of street outreach and visits to hostels/day centres and then directed to the fixed site clinic. Otherwise clients may simply present themselves and the aim is for all patients to get treatment appropriate to their needs

-

8

Treatment at other non-dedicated CDS clinics offering sedation and specialised services. The Salaried primary dental care services: toolkit for commissioners14 advised commissioners to provide a comprehensive and proactive oral healthcare service for people of all ages who have special needs. The CDS provides all the necessary dental care and treatment for those patients in TH and CH who have special needs, which are defined as moderate, severe or extreme, including the specified advanced mandatory services, which are: dental treatment under sedation for children and adults, orthodontics and restorative dentistry. People who access CDS outreach services can be transferred to fixed sites to access treatment under sedation, and treatment with specialists in endodontics/prosthodontics if needed. The fixed sites are in five different locations in TH and CH and care is provided in 18 surgeries, by a team of dentists and dental care professionals, many of whom are also specialists in special care dentistry.

-

9

NHS emergency dental services (EDS) provided evenings and weekends managed by the CDS.

When providing a service, especially for 'hard to reach' people, it is crucial to constantly monitor the outcomes for the patients, ensuring the service provides the appropriate clinical mode of treatment8 and has numerous points of entry and 'safety nets'. To this aim, the CDS set objectives for the dedicated homeless dental service:

-

1

To increase the accessibility of dental care to homeless people

-

2

To decrease the amount of clinical time lost due to failed or cancelled appointments

-

3

To complete appropriate treatment plans for all patients

-

4

To provide the full range of dental treatments (bands 1-3)

-

5

To see all emergency patients that day

-

6

To obtain feedback and evaluation of the service from service users, stakeholders and dental teams and respond to the findings.

By conducting a record card audit, an analysis of appointment books, service delivery rotas, day sheets and feedback forms, this study describes the outcomes of the dental care provided by TH and CH CDS for adult homeless people in East London over a 30 month period, April 2009 to September 2011, and evaluates these findings against the objectives set for the service.

Method

A random sample (n = 100) of all the record cards of adult patients identified as homeless attending the DDS in the period April 2009 to September 2011, and a random sample (n = 250) of all the record cards of adult patients identified as homeless attending the dedicated MDS in the same period was undertaken. A data form was developed to allow consistent abstraction of data from the case notes and allow comparison with other studies.9 Predisposing variables9 collected were age, gender, ethnicity and homelessness. Three broad categories of homelessness were used in the study. 'Rough sleepers' were defined as people with no permanent or temporary residence, 'who sleep on the street from very late at night to the early hours'. 'Hostel and night shelter dwellers' were defined as homeless people who resided in hostels and night shelters and other forms of temporary accommodation – women's refuge, asylum seekers in temporary bed and breakfast and guest houses were included. 'Rehoused' homeless people were defined as those who had experience of homelessness but were now residing in a permanent residence, although still in contact and accessing social and housing support services specifically for homeless people. There was some overlap with the dental services the CDS provided for 'substance misusers', but if they were not homeless at the time of using the service their data was not included.

Enabling variables collected9 were related to contact with medical and dental services and receipt of public benefits. Factors relating to need that were included were presence of a health issue impacting on the delivery of dental care, patients' expressed need (presenting complaint at the first contact with the dental service), and evaluated need (pre-treatment dental need). Patterns of dental service use, treatments provided, outcomes of care, challenges and feedback received from the service users were recorded.

From appointment books to service delivery rotas and day sheets, a comparison was made between levels of activity in three ten-month periods, April 2009 - January 2010, February 2010 - November 2010 and December 2010 - September 2011, between domiciliary visits, MDS, DDS and CDS clinic. The review was undertaken as a retrospective audit and research ethics approval was not sought. All data were anonymised and abstracted directly onto a password-protected computer.

Data analysis

Descriptive and summary analyses were produced for each variable. Bivariate analyses were then conducted assessing the relationship between service use and the overall outcomes of care ('presenting complaint met' and 'treatment completed'). 'Presenting complaint met' was defined as the patient receiving the treatment requested during the course of treatment. 'Treatment completed' was defined as completion of the patient's treatment plan as determined by the dentist.9 The level of statistical significance was set at 0.05 and SPSS version 17 was used.

Results

During April 2009 to September 2011, 1,728 appointments were provided for homeless people from the dedicated MDS, 681 (39%) of these appointments went to the 250 patients whose record cards were obtained from the MDS. During April 2009 to September 2011, 1,374 appointments were provided for homeless people from the dedicated DDS and 39.1% of these appointments went to the 100 patients whose record cards were examined as part of this audit. One of the record cards randomly selected from the MDS had incomplete data and was excluded from the results, so data is presented on the 349 complete record cards from the two services. The age range of the homeless patients was 18-74 years, with a mean age of 38.46 years ±9.1 standard deviation (SD) with 80% of the patients (n = 281) under 50 years of age. There was no significant difference in the mean age of the patients accessing the DDS compared to the MDS (Fig. 1) but 30.5% of the MDS patients were under 30 years old compared to 12% of the DDS patients.

Over the 30 month period there was a small number of homeless people accessing the CDS and having domiciliary care, but there was nobody who was homeless who accessed the EDS. Table 3 shows the percentage of patients seen by the CDS who were homeless and highlights changes over that time. Although a large percentage of patients at the DDS were homeless when compared to other CDS clinics, patients at this clinic also had other special care needs, such as complex medical problems and mental health problems, so although they may have been homeless in the past, this was no longer their main issue. Figure 2 shows the total number of appointments offered by the MDS in comparison to the rest of the CDS and how the service increased over the 30 months. The number of appointments patients attended in the MDS increased significantly over the period (Χ2, p <0.001, df 2), this was due to both the number of sessions increasing from 82 in the first ten months to 226 in the last ten months and so the number of appointments offered increased. However, the average number of patients seen per session rose from 2.9 to 4.4, as the lost clinical time reduced for the sessions (Table 3). This reduction in lost time was due to the changes and development in the MDS as a result of feedback from everyone involved in the service. The number of appointment spaces not refilled when patients cancelled or failed to attend fell from 28% to 15% over the same time period.

There were 295 men (84.5%) and 53 women (15.5%) included in the sample. Ethnicity data was collected for all patients seen in the CDS. Of this sample (349 people), 12 patients refused to give their ethnicity (3.4%), 41.3% (n = 144) described themselves as Eastern European, 26.4% (n = 92) described themselves as white Irish/English, 8.6% (n = 30) described themselves as Bangladeshi, 11% Black British, 4.5% Caribbean and less than 2% other mixed, 1% Asian and 2% African. There was no significant difference in ethnicity between patients attending the DDS compared to the MDS. The mean age of the Eastern Europeans (35.05 years) was slightly less than for white Irish/English (42.28 years) but not significantly. Two hundred and eighty patients (80%) were in receipt of benefits, with significant differences between the largest three ethnic groups, with only 49% of patients from Eastern Europe in receipt of benefits compared to 97% of the Irish/English patients and 81% of the Bangladeshi patients (Χ2, p <0.001, df 2). Only 5% of the patients attending the DDS were not in receipt of benefits compared to 25% accessing the MDS. This receipt of benefits affected the uptake of continuing dental care.

Two hundred and ninety one (83.4%) patients were staying in a hostel at the time they were asked, 19 (5.4%) were rehoused in more permanent accommodation, 26 (7.5%) said they were 'rough sleeping' and 12 said they were in temporary accommodation. There were significantly more rough sleepers accessing the MDS (n = 25, 10%) compared to the DDS (n = 1, 1%). The prevalence of self-reported 'mental health' problems, anxiety and depression, was 55%. Sixteen people reported that they were Hepatitis C carriers and 6 had HIV, only 15 (4.3%) reported that they were dental phobic and 16% had other medical problems. Two hundred and seventy-two (78%) patients smoked, with 86% (n = 234) of these people saying they also consumed alcohol daily and 29% (n = 79) using drugs regularly. Of the non-smokers (n = 77), 3% consumed alcohol daily and 5% of the population were past substance misusers who had now ceased drug use. No patients who said they currently took drugs were non-smokers.

Not a single MDS user said they were registered with a dentist – the time since last visiting a dentist ranged from 'never' to one year ago and the majority reported that they were 'non-attendees' (86%) compared to 'irregular attendees' (12%) and regular attendees (2%, though it should be noted this 2% included those who viewed their 'prison dentist' as their regular dentist). From the DDS, 24% of the patients regarded the clinic as their dentist and had attended previously. Only 2 of these 24 patients had visited within the last year but all had been within the last three years. Four patients said they were registered in the past with other dentists but had not been within the last year and 72 patients reported they had no dentist, with 56 patients saying they had 'never' been to a dentist.

Expressed need

The patients' most common expressed need (40%, n = 140) was severe or constant pain. Four percent of patients complained of swelling and infection (n = 14), 4% (n = 14) complained of sensitivity, 1.4% trauma (n = 5), 7% (n = 25) presented with problems relating to bleeding gums and 'wobbly teeth', 6.9% complained of lost restorations (n = 24), 3% (n = 11) had sharp teeth, 27.5% presented requesting a check-up (n = 96) and 19 (5.5%) patients wanted a denture or had denture problems. The expressed need variables did not predict subsequent attendance.

Evaluated need

Treatment need was determined from the treatment plans prepared and discussed with the patient at the first contact visit with the service. Treatment needs were extensive and reflected the high mean number of decayed and infected teeth in the sample, with 99% (n = 346) of people requiring treatment for dental decay, infection secondary to dental decay, severe periodontal disease leading to infection and swelling, recurrent decay, root caries and retained decayed roots. Only nine people had no decay, six were dentate and decay-free and three were edentulous.

Pattern of MDS/DDS use and outcomes of care

Out of the 349 patients with complete data, 346 (99%) were judged to be in need of further care, though 128 (36.7%) patients were lost after the first appointment and this was significantly related to drug use (p <0.01), ethnicity (p <0.001) and whether they were receiving benefits (p <0.01). It was not related to age, type of accommodation, medical history or treatment expressed or received. More patients were lost after a first appointment from the MDS (n = 115, 46.2%) than the DDS (n = 13, 13%). However, only 15 (11.7%) of those 128 did not receive any treatment at their first appointment, most had been treated for pain with temporary fillings, extractions, permanent fillings and drainage of swellings or had received their requested dental examination and prevention had begun.

It had been agreed that all emergencies would be seen and treated that day/session. In the MDS, 135 (54%) people in the sample first presented as an emergency or 'drop-in' without a booked appointment and 61 of these patients (45%) were not in receipt of benefits and had no means to pay and were never seen again after the first emergency appointment. A significant number (n = 53, 87% p <0.0001) of these patients stated their ethnicity was Eastern European. All patients not in receipt of benefits had HC113 forms completed, and some did return to complete treatment once the HC2 certificate had arrived. However, due to treating patients unable to pay or not on benefit, the service lost 73.2 UDAs over the 30 months. Another eight patients, who were on benefits and could have accessed further treatment without recourse to form filling, also did not return after emergency management. For non-emergencies, those patients not receiving benefits had HC1 forms completed and were seen once the HC2 certificates had arrived and those in receipt of benefits were allocated appointments. In comparison, at the DDS 13 people presented as an emergency/drop-in (13%) and only 2 of these were not in receipt of benefits and had no means to pay. A total of 7.2 UDAs were lost from the all the patients in the DDS over the 30 months.

Two hundred and thirteen (61%) patients completed their treatments, taking 1 to 18 appointments, with 42% of MDS users completing treatment compared to 67% of DDS users. A course of treatment was deemed to be complete when the treatment plan designed at the first contact had been completed and the patient had no other outstanding treatment needs. Out of the total 349 patients, only 97 (27.8%) completed a course of treatment without any failed or cancelled appointments. Of the 128 (36.7%) patients who were lost after the first appointment without completing their treatment plan, only 18 (5.2%) did not receive any treatment; most had been treated for pain with temporary fillings, extractions, permanent fillings and management of swelling. The submitted FP17 forms, not including the 61 patients from the MDS and 5 patients from the DDS for which no forms were submitted, consisted of 67 band 1 courses of treatment, 16 band 1.2 (emergency only), 148 band 2 and 52 band 3, with one patient referred to hospital for a pre-cancerous lesion and two patients referred to the CDS fixed site clinic for treatment with the specialist in prosthodontics. No patients were referred for treatment under sedation.

The band 3 courses of treatment consisted of partial and full dentures, crowns and adhesive anterior bridges, they also included all band 2 treatments, for example one patient had 19 roots extracted and then upper and lower full dentures under one band 3 course. Band 3 treatments accounted for all of the 7-18 appointment treatment courses and some of the 4-6 appointment courses. Only one band 3 treatment was incomplete, although all the patients in these longer courses of treatment had failed or cancelled at least one appointment. The band 3 courses of treatment were significantly related to the age of the patient (mean age 48.2 years p <0.001), ethnicity (p <0.01), drug use (p <0.01) and being in receipt of benefits (p <0.001), although no band 3 course of treatment would have started without the exemption status of the patient being clarified. However, it was not related to type of accommodation or gender of the patients.

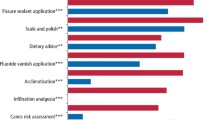

The mean number of visits for band 2 treatments (exam, X-rays, scaling and polishing teeth, fluoride application, prevention advice, smoking/alcohol cessation advice, restorations, extractions, root canal treatments) was 2.9 ± SD1.8 and 54% of these treatments were completed within one month. Only two patients had more than one course of treatment over the 30 months and their second course has not been included in the sample. The treatments in band 2 ranged from eight offered appointments for one patient over a period of 12 weeks, of which they failed to attend two, and had ten fillings and eight extractions, to other patients who had one to two extractions and one to two fillings in one to two appointments (Figs 3 and 4). Use of the MDS/DDS enabled patients to undergo all dental procedures, including root canal treatments and surgical extractions.

While only 61% fully completed treatment as judged by the dentist, a further 28.5% nearly completed their treatment and only 5% had no treatment at all. Ninety-five percent of the patients had some dental management of their presenting complaint and although the dentist may not have judged this as definitive treatment, it may have satisfied the patients' expressed need.

Feedback

The feedback from the dental teams highlighted many challenges (Table 2). Feedback from stakeholders included the request for flexible session times to support ease of access for their clients, willingness of dental staff to work with difficult or disturbed clients, the ability to offer a dental service on site and ability to get all clients out of pain within that day. The feedback from the service users was positive, except for the NHS fees, which they felt were unaffordable. The patients (100%) liked having the LW as the first contact and requested consistent dental teams, however, when these were female the appreciation of them was sometimes a bit too enthusiastic. The response to questions, were you treated with dignity and respect? Was treatment explained to you? And how helpful were staff with your concerns? Were all 100% positive. The clients (25%) wanted more services and daily access rather than weekly and one client felt their appointment was too short.

Discussion

Dental care for homeless people could be provided at a conventional location, within the GDS, however, this seems problematic for this group.4,6,8 Their increased prevalence of ill-health, chaotic lifestyles, deprivation and social exclusion suggest a dedicated service is more appropriate to their special needs. Treatment opportunities (such as mobile clinics with other health professionals in hostel localities) must be provided in conjunction with consultation and essential assistance from healthcare coordinators for homeless populations.4 The office of the Deputy Prime Minister and the Department of Health have issued guidance10 for all those involved in delivering health services to homeless and vulnerable people on developing shared positive outcomes. The guidance was published alongside a policy brief on addressing the health needs of homeless people. The BDA report8 includes a seven-point plan calling for a flexible dental service that responds to the particular needs of homeless people by employing a combination of conventional and outreach locations to deliver care. Nevertheless, some notes of caution have been sounded. The provision of outreach care in collaboration with faith-based agencies may raise issues regarding the need to provide a service open to all. It has also been suggested that providing dedicated services for homeless people may have the unintended consequence of making them ghettoised and excluded from mainstream primary care. This view does, however, seem to have been effectively discredited, given the role that dedicated medical services have now been seen to play in helping homeless people out of homelessness.15 Likewise, the TH and CH CDS nine tier service delivery model for homeless people is aimed at eliminating any possible discrimination and to promote equality in disability, race and gender and enable everyone to access oral care.

TH and CH CDS have been providing care for homeless people for many years from a DDS supplemented by a MDS. From 2009, a decision was made by the CDS to increase the accessibility of dental care to homeless people. A key theme in dedicated healthcare provision for homeless people is that of fixed-site provision at a dedicated location that is easily accessed by homeless people (DDS), however, the CDOT following discussion with stakeholders felt that many homeless people were not accessing the DDS and the MDS had a strong role to play. During the 30 month period in this study, the homeless patients accessing the DDS stayed constant yet those accessing MDS increased significantly (Χ2, p <0.001, df 2). This has similarly been found when providing care to poor families or those from deprived areas via a MDS. The provision of a MDS at a primary school in a socially deprived, multi-ethnic area markedly increased the uptake and completion of treatment after a school dental inspection. Eighty-one percent of children who were offered treatment in the mobile clinic accepted it and 91% of these completed it. In the previous year, when care was offered at a health centre within half a mile of the school, the corresponding figures were 43% and 4%. Over half the children seen in the mobile clinic had not previously visited a dentist.16 This not only compares with the service uptake between the MDS and DDS over the period, but stresses the importance of location; if the location of the MDS changed even to the other side of a road or round a corner, then the homeless clients would not access care. The MDS also seemed to provide care to a different homeless client group than the DDS – there were more young people, less of them were in receipt of benefits, there were more emergency appointments and more oral trauma was seen on the MDS. There were also more homeless who were 'rough sleepers' and less band 3 courses of treatment on the MDS.

However, the provision of a MDS comes with considerable costs. Planning and operating a MDS requires serious consideration of many logistical factors including staffing, maintenance, repairs, insurance and commitment of staff. From a financial perspective, they require a high capital investment. Direct costs include staff costs, dentists, dental nurses, outreach support staff, LWs, instruments, consumables and laboratory bills etc. Indirect costs include driver's services, vehicle maintenance and repair, vehicle insurance, cleaning, fuel, dental equipment maintenance and repair, office expenses and vehicle registration. The cost of a unit of dental activity (UDA) on a fixed site clinic is x, that UDA cost when provided on a MDS on a homeless service is 2.4x compared to a domiciliary visit UDA of 1.4x. MDS require careful assessment for access to a site, time to set up, organisation of the steps, stabilisers, power, water supply, set up of the surgery and then close down each day, when everything has to be re-locked and stowed. There can be problems to local communities with noise and congestion from traffic. There can be problems with the dental surgery having effective stock control, wrong MDS delivered to the wrong site, missing dental records, generator breakdown/faults, missing lab work, adverse weather: too hot/too cold/ice/snow, the parking bay not suspended by the council, roadworks, cars parked in suspended bays, steps broken/lift broken, traffic delays and vandalism. Sessions are also lost due to staff holiday/sickness, staff training (as all staff need to be inducted on MDS use and procedures), downtime for MDS (rest periods) and vehicle servicing, equipment maintenance, deep cleans etc. The MDS needs to be cleaned after return at night or early in the morning, which means early or late shifts for staff and also records, appointment books and laboratory work need to be removed and then set up again the following day. In a 52 week year the MDS year is based on 42 weeks. However, although the cost of the MDS is high, it is less than the cost of a hospital admission due to oral infection or swelling, which may have occurred if the homeless patients had not accessed care on the MDS. There is also the incalculable benefit of relief of pain, improved self-esteem and improved oral function for the patients treated.

To meet the objective of decreasing the amount of clinical time lost due to failed/cancelled appointments, intense effort was exerted from the LW and the CDOT (Table 3). They contacted the stakeholders to enlist their commitment and support, giving information on how people could access all dental services, location of existing services, NHS charges and exemptions, service delivery models, inclusion of oral care on the agenda for team meetings, staff handovers and feedback from the organisations and users. The CDOT developed a very simple oral health assessment tool that organisations include at the assessment interview for all new and existing clients, so that any oral problems are identified and the client is referred directly to the CDS. They worked jointly with partner organisations agreeing a bespoke service model to meet the care and access needs of the client group. This often varied according to the type of homelessness the client group was experiencing. The CDOT provided targeted screening and referral programmes at smaller organisations where clients struggled to access treatment locations. By working closely with smaller organisations in this way, it ensured the widest possible reach for homeless patients and also offered the most flexible and extensive model of service provision.

For example, at one centre, Dellow (Table 1) there is an open session first thing in the morning, when lots of people arrive for breakfast, followed by some of these clients being offered appointments for dental treatment later that day. There is a dedicated LW for the service, who has a contact number where possible for all patients, so they can ring and remind both the patients and their key workers both the day before and on the day of the appointment. They go into the centre to search for the patients and keep a list of waiting patients so that any appointments vacated by a patient cancelling or failing to attend is refilled. A nearby residential hostel for homeless men access the same MDS on that day and to recognise that these clients are living a more stable life, there is more emphasis on treatment appointments, attendance of which is supported by hostel staff and sometimes it is these clients who are contacted to fill the appointment slots vacated by the hostel non-attendees. Some patients, who are on rehabilitation programmes, are even more stable and are able to be referred into an adjacent clinic for more complex dental work. The Dellow centre is given information about the uptake and care provided on the MDS, types of dental treatments provided, number of appointments, number of appointments not kept and problems encountered. The service users, the stakeholders, the dental staff and the LW all complete evaluation forms on their experience. The dental service also provides toothpaste and a toothbrush as part of a welcome pack for new arrivals to help improve the dental hygiene of the client group as well as at the LW access and information sessions. Although treatment plans are not always completed, patient feedback has suggested that improvement in appearance, for those seeking employment for instance, is a common motivating factor in patients turning up for treatment.

The main barrier for homeless people accessing dental care in the MDS appeared to be cost of treatment. While an objective of the service was to provide the full range of dental treatments (band 1-3), for those patients not exempt from NHS charges this appeared too expensive for homeless people. Although exemptions exist for certain groups of patients, such as those on benefits or those under 18,13 these may not necessarily apply to homeless people, who may also have difficulty in proving their eligibility. Some people just had no means to pay for treatment and therefore could only be provided with emergency care and not a full course of treatment. An objective was that all emergencies would be seen and treated that day/session, which was achieved. In the MDS, 54% of people in the sample first presented as an emergency or 'drop-in' without a booked appointment and 45% of these patients were not in receipt of benefits, had no means to pay and were never seen again after the first emergency appointment. A significant number (n = 53, 87% p <0.0001) of these patients stated their ethnicity was Eastern European. Those patients who do not return for treatment because they are unable to pay are of great concern to the service. Although they will always receive free treatment for emergencies, it would be far more beneficial to their general and oral health to be able to offer them free band 2 courses of treatments with a structured treatment plan than emergency only care.

Other barriers included the difficulty of keeping appointments, as homeless people can have chaotic lives with no fixed address or may move frequently between temporary accommodation and oral and dental health are often low on homeless people's hierarchy of needs. These barriers to access resulted in the development of more inventive and creative ways of delivering dentistry to this group (Table 2).

An inherent weakness of a retrospective case-note review is the problems of missing data, which must be acknowledged as a limitation in the present study. The sample in this study drew on homeless people from a variety of housing situations in East London and while it included rough sleepers, the majority of patients resided in hostels. The sample was representative of homeless people who used the targeted MDS and DDS and is reflective of the pattern of homelessness in East London only during this period of time. It is hypothesised that the presence of the MDS promoted uptake of dental care among homeless people, as before contact with the MDS, only 2% of people had a regular source of dental care. The targeted MDS was organised completely around the particular needs of homeless people and only located in places where homeless people congregated.

Daly et al.9 found in their study that 18% of patients completed treatment as judged by the dentist; a further 4% required some minor further work and two people had completed primary dental care and were awaiting referral to a specialist. In all, 68% of the 204 patients in the sample in South London did not complete treatment. The results of our study showed that 61% fully completed treatment as judged by the dentist, a further 28.5% nearly completed their treatment and only 5% had no treatment. In all, 95% of the patients had some dental management of their presenting complaint and this may have been all 'the treatment' that they desired at that time. Thus the objective to complete 'appropriate treatment plans' for all patients was achieved at some level. This was due to the commitment of all the CDS staff, the planning and the engagement with the community and stakeholders and the adaptions made (Table 2). The way in which the dental care is organised is an important factor in promoting healthcare utilisation. A high proportion of people using the dental service were able to attend via the 'drop-in' clinical sessions. Flexible modes of delivery and use of mobiles and outreach clinics have been suggested as ways of improving access to healthcare for homeless people.5,8,15 This agrees with Daly et al.9 who hypothesised that an MDS providing a full range of treatment might be a better model to promote continuity of care than the simple triage provided in their outreach clinic sessions. Daly et al. reported that 'while the 'drop-in' clinics allowed flexibility in usage, it meant that no treatment could last for more than 30 minutes. Patients had to wait all morning for their 'drop-in' slot and make extra visits to complete treatment over a greater period of time.'9 The MDS attempted to overcome this by allowing people to wait in the hostels/day centres and then going to collect them, thus appointments could last longer. Also the service aimed to start treatment at first visits and attempted realistic treatment plans that were as close to the patients' expressed need as possible. The LWs also worked very closely with key workers so that the patients understood the treatment plans and aims. Homeless people themselves decided the frequency of their attendances. The flexibility of the service itself could have been a barrier to continuity of care as suggested by Daly, but in this study, many of the homeless people knew the locations of the MDS during the week and if missed an appointment at one location, could present themselves at another. Some users preferred and coped with an appointment rather than a 'drop-in' slot and some did not. Additionally, on the MDS, information is given about the DDS, which is available for appointments four days a week. Some patients originally attending the MDS were later transferred to the DDS and organisations could also refer patients to the DDS if they had no current MDS service.

While the data are not strictly comparable with national UK data, most homeless people presenting to the MDS/DDS had higher levels of normative dental need compared with their equivalent age group in the housed population.7 Seventy percent of those presenting to the MDS and DDS expressed a need in relation to oral pain, disease and tissue damage. Only 27.5% presented requesting a check-up. This agrees with the findings of Daly et al. and challenges the received view that homeless people have a low perception of felt need and are apathetic about their oral health.9 In agreement with Daly's study there was no difference in the way different categories of homeless people used the service in terms of visiting, visits per course, presenting complaint met and treatment completed, but because treatment was not free in this study, the biggest difference in uptake of dental care was whether the patient was in receipt of benefits or not.

Although approximately 80% of homeless people in the present study had medical conditions that had an impact on their dental care, most care was readily provided in the primary care setting as has also been reported elsewhere.17 Two hundred and seventy-two (78%) patients smoked, with 86% (n = 234) of these people saying they also consumed alcohol daily and 29% (n = 79) used drugs regularly. Of the non-smokers (n = 77), 3% consumed alcohol daily and 5% of the population were past substance misusers who had now ceased drug use. The recent systematic review by Hanioka et al.17 indicated that the odds of losing teeth are two to four times higher in smokers than non-smokers. Alcohol consumption has been linked to periodontitis19 and tooth wear20 and both smoking and alcohol are closely linked to the incidence of oral cancer.21 The incidence of oral cancer is also strongly related to social and economic deprivation,22 particularly for men, and this widening inequalities gap makes it all the more important that all avenues to address possible risk factors are explored. All patient examinations in the CDS include smoking and alcohol cessation advice related to risks of oral disease and cancer.23,24 It has been shown that patients have very positive attitudes towards the role of dentists in smoking and alcohol cessation activities and that dentist's have a great potential to motivate people to stop smoking. The MDS and DDS attracted concentrated numbers of patients whose lifestyle habits place them at risk of developing oral cancer. The service could therefore play a significant role in primary prevention of this disease.

Conclusion

Many factors contribute to poor dental and oral health among homeless people and ensure that they remain a high-risk group for oral and dental disease. Dental services should form an integral part of primary care for this group, involving multi-disciplinary working between GPs, mental health services, addiction services and podiatry. It is important that other services and agencies working with homeless people are aware of their dental care needs and link into dental services provided locally. Healthcare provision has to be targeted rationally at those who experience the greatest risk, the greatest need and the greatest difficulty in obtaining access, with care effectively tailored to their specific needs and circumstances.8

The aim of this study was to report the outcomes of the dental care provided by the CDS in TH and CH for adult homeless people in 2009-2011 and evaluate it against planned objectives of accessibility, efficiency and appropriateness. Thus leading to an examination of the service effectiveness and quality of treatment, completion of care (courses of treatment) and efficient resource use not just based upon the numbers of clients seen. This was all conducted so the CDS can develop the most relevant and appropriate way to provide dental services to people affected by homelessness. The study showed a significant need for services providing oral healthcare for this population and that flexibly delivered dental services, embedded in local health and social networks, seemed to promote uptake in these clients who normally find it extremely difficult to find dental care services elsewhere.

It is, however, acknowledged that addressing the health consequences of homelessness is a form of secondary prevention – reducing the harm resulting from long-standing and increasing inequality in society. We recognise that in the long-term, primary prevention is the only rational response – reducing poverty and inequality to tackle the root causes of homelessness and multiple disadvantages.25

References

Robbins J L, Wenger L, Lorvick J, Shiboski C, Kral A H . Health and oral health care needs and health care-seeking behaviour among homeless injection drug users in San Francisco. J Urban Health 2010; 87: 920–930.

Seirawan H, Elizondo L K, Nathason N, Mulligan R . The oral health conditions of the homeless in downtown Los Angeles. J Calif Dent Assoc 2010; 38: 681–688.

Okunseri C, Girgis D, Self K, Jackson S, McGinley E L, Tarima S S . Factors associated with reported need for dental care among people who are homeless using assistance programs. Spec Care Dent 2010; 30: 146–150.

Collins J, Freeman R . Homeless in North and West Belfast: an oral health needs assessment. Br Dent J 2007; 202: E31.

Daly B, Newton T, Batchelor P, Jones K . Oral health care needs and oral health-related quality of life (OHIP-14) in homeless people. Comm Dent Oral Epidemiol 2010; 38: 136–144.

Smile4life. Report of the homeless oral health survey in Scotland 2008–2009. Dundee: Smile4life, 2011.

Kelly M, Steele J, Nuttall N et al. Adult dental health survey 1998. London: Office for National Statistics, 1998.

British Dental Association. Dental care for homeless people. London: BDA, 2003.

Daly B, Newton J T, Batchelor P . Patterns of dental service use among homeless people using a targeted service. J Public Health Dent 2010; 70: 45–51.

Department of Health. Homelessness and health information sheet. Number 3: dental services. London: Crown copyright, 2005.

Currie D, Irwin R . Atlas of services for homeless people in London. London: London Housing Foundation, 2009.

Tower Hamlets homelessness strategy 2008–2013. London: London Borough of Tower Hamlets, 2008.

NHS. HC11-Help with health costs. London: Crown copyright, 2009.

Salaried Primary Dental Care Services. Toolkit for commissioners. London: Primary Care Commissioning, 2010.

Quilgars D, Pleace N . Delivering health care to homeless people: an effectiveness review. Edinburgh: NHS Scotland, 2003.

Clarke J R, Bradnock G, Hamburger R . The uptake and completion of dental treatment using a mobile clinic in central Birmingham UK. Community Dent Health 1992; 9: 181–185.

Cembrowicz S, Farrell S . Arranging dental care for hostel dwellers: a pilot project. Br Dent J 1992; 172: 436.

Hanioka T, Ojima M, Tanaka K, Matsuo K, Sato F, Tanaka H . Causal assessment of smoking and tooth loss: a systematic review of observational studies. BMC Public Health 2011; 11: 221.

Amaral Cda S, Luiz R R, Leão A T . The relationship between alcohol dependence and periodontal disease. J Periodontol 2008; 79: 993–998.

Robb N D, Smith B G . Prevalence of pathological tooth wear in patients with chronic alcoholism. Br Dent J 1990; 169: 367–369.

Hashibe M, Brennan P, Benhamou S et al. Alcohol drinking in never users of tobacco, cigarette smoking in never drinkers, and the risk of head and neck cancer: pooled analysis in the International Head and Neck Cancer Epidemiology Consortium. J Natl Cancer Inst 2007; 99: 777–789.

Conway D I, Petticrew M, Marlborough H, Berthiller J, Hashibe M, Macpherson L M . Socioeconomic inequalities and oral cancer risk: a systematic review and meta-analysis of case-control studies. Int J Cancer 2008; 122: 2811–2819.

Kaner E F, Bayer F, Dickinson H O et al. Effectiveness of brief alcohol interventions in primary care populations. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2007; 2: CD004148.

National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Brief interventions and referral for smoking cessation in primary care and other settings. Public health intervention guidance 1. London: NICE, 2006.

Hewett N . Standards for commissioners and service providers. The faculty for homeless health version 1.0. London: London Pathway, 2011.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Refereed paper

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Simons, D., Pearson, N. & Movasaghi, Z. Developing dental services for homeless people in East London. Br Dent J 213, E11 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.2012.891

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.2012.891

This article is cited by

-

Models of dental care for people experiencing homelessness in the UK: a scoping review of the literature

British Dental Journal (2023)

-

Best practice models for dental care delivery for people experiencing homelessness

British Dental Journal (2023)

-

Top tips for managing people who experience homelessness and social exclusion in primary care

British Dental Journal (2023)

-

Developing a voluntary initiative for homeless populations in general dental practice

British Dental Journal (2022)

-

A survey of dental services in England providing targeted care for people experiencing social exclusion: mapping and dimensions of access

British Dental Journal (2022)