Key Points

-

Restrictive dental contracts in the North East provided the majority of their dental care to residents of the more affluent lower super output areas.

-

However, restrictive dental contracts did provide some dental care to residents of the most deprived lower super output areas.

-

Commissioners should carefully consider the impact of ending restrictive contracts on access to dental services for their local populations.

Abstract

Aim To determine if restrictive NHS contracts are of benefit in addressing health inequalities in oral health, by using an ecological approach based upon an area measure of material deprivation.

Methods Postcodes of patients seen under all the restrictive contracts (49) within the North East of England were identified and matched to lower super output areas. The deprivation scores were identified for each area using the Index of Multiple Deprivation 2007. The proportion of patients within each area was calculated and divided into deciles for England, from the most to the least deprived areas.

Results 33,341 postcodes were identifiable from datasets supplied for the study in the North East; a further 4% were invalid. There was inequity in the distribution of patients, with proportionately more patients from the least deprived deciles and less patients from the more deprived deciles seen under the contracts. However, many thousands of patients identified lived in the most deprived areas.

Conclusions Restrictive contracts may be of benefit in addressing health inequalities. PCTs need to carefully consider the impact of ending restrictive contracts on their local populations.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

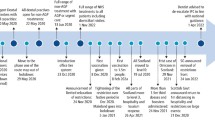

A new NHS dental contract was introduced for all independent dental contractors in England in 2006. The period before the implementation of the contract was marked by rigorous debate between the dental profession and the Department of Health (DoH).

One of the most controversial initial proposals in the new contract was that dentists who restricted their NHS services to children and patients exempt from paying dental charges would either have to accept a contract to see all patient groups or not take on a contract at all under the new arrangements.1

The British Dental Association publicly stated that 'The BDA is concerned that priority groups could be put at risk of losing access where primary care trusts are not prepared to offer dentists contracts to treat children and adults who are exempt from charges,' and 'In areas where this does happen, it will do nothing to ease health inequalities which exist.'2

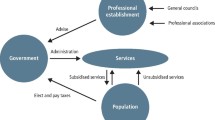

In response to these concerns, the DoH allowed primary care trusts (PCTs) to negotiate child-only and restricted contracts with dentists if they so wished.3 This resulted in most health bodies agreeing to restrictive contracts where dentists had previously seen a limited range of patients.4 The DoH has subsequently become far less supportive of PCTs allowing restrictive contracts and does not encourage their continued use.5

The aim of this paper is to use an ecological approach to determine if restrictive contracts have any value in addressing health inequalities. Tackling health inequalities is the sixth competence which commissioning PCTs must have as part of their responsibilities under the World Class Commissioning Programme.6

Previous studies carried out both locally in the North East and nationally have demonstrated that there is a strong association between deprivation and lower social class and experience of dental disease.7,8 Those people living in the most deprived areas experience the greatest levels of dental disease.

Deprivation can be measured in a number of ways. The method currently in most widespread use in England is the Index of Multiple Deprivation (IMD) 2007. The IMD brings together 37 different indicators which cover specific aspects or dimensions of deprivation: income, employment, health and disability, education, skills and training, barriers to housing and services, living environment, and crime. These various elements are weighted and combined to create the overall IMD 2007. It identifies levels of deprivation in small areas called lower super output areas (LSOA). Each area contains on average 1,500 people. In England there are 32,482 lower super output areas.9

Settings

The North East of England is the smallest Government Office region in England; it has a population of approximately 2.5 million people and is a relatively deprived area, with an excess of deprived LSOA compared to national (English) norms. It has approximately 18% of LSOA in the most deprived 10% (decile) of areas in England.10

The North East is made up of two densely populated urban areas containing the conurbations of Tyne and Wear and Teesside, with a combined population of 1.4 million, and the more rural areas of County Durham and Northumberland, which have a population of 900,000. The North East has 1,656 LSOA within it.

Study Population

Forty-nine contracts were identified in the North East which were limited to restricted groups of patients. Seventeen contracts were with practices situated in the rural areas of County Durham and Northumberland; the remainder were located in the conurbations of Tyne and Wear and Teesside. Data from the Business Services Agency identified postcodes for 34,655 individual patients who were seen under these contracts in 2007/2008; 72% of the activity was for persons under 18 years old.

Methods

All the dental practices in the North East of England with restrictive contracts were identified. The Business Services Agency supplied all the postcodes for patients seen under these contracts during the year 2007/2008. The postcodes were then mapped to their appropriate LSOA for the North East along with their IMD score and LSOA ranking for England. This data was then divided into deciles, providing groupings according to the level of deprivation observed in all the LSOA in England.

Results

From the data supplied, there were 33,341 postcodes ascribed to locations in the North East of England, which was 96% of the postcode dataset. The un-ascribed 4% were either for postcodes from locations outside the North East of England or due to unknown, incomplete or invalid postcodes.

The IMD 2007 rankings of the LSOA were in the range of 14 to 32,000. Division of the postcodes into deciles from the most deprived to the least deprived LSOA in England was performed, as well as the proportions of observations against the regional proportions of areas; this is shown in Table 1.

The Table shows that there were proportionally more postcodes for LSOA in the least deprived deciles in the North East compared to the regional proportions of LSOA for each decile. This was associated with lower proportions in the more deprived areas compared to the regional norms. However, in absolute numbers there were many thousands of postcodes related to areas in the most deprived LSOA in the North East.

Discussion

The results demonstrating that many thousands of patients living in the 10% most deprived areas of the North East had received care from dentists who had restrictive contracts and who had significant private practice, were unexpected findings from this study. The reasons for this are unclear but may be due to the measurement of deprivation and how it is constructed.

The index used for measuring deprivation among communities in England is the measure which is in most widespread use at the present time. However, an LSOA will describe a geographic area and not an individual address in that area. It would thus be possible to have a large deprived housing estate within a single LSOA associated with a small number of executive-style private houses, producing an overall high deprivation score, even though some individual residents would be affluent.

The degree of heterogeneity within LSOA is likely to be much larger in rural areas because of the lower population density. Part of the study area covered the rural areas of County Durham and Northumberland.

Thus the patients identified in this study as living in very deprived areas may have been selected out as being affluent sections of their local community since the LSOA measure is an area score and not a personal measure of an individual's level of affluence or poverty.

Conclusions

There is evidence from this study to suggest that restrictive contracts may have some value in providing care for some patients living in the most deprived sections of the community and so addressing health inequalities in oral disease. The resources currently in restrictive contracts do, however, demonstrate inequity in service provision with proportionally more care provided for populations in less deprived areas and consequently these patients are more likely to have lower clinical need.

PCTs, when considering the future of restrictive contracts, need to consider carefully the impact of any proposed changes, recognising that some patients living in deprived areas in their communities are likely to be receiving services under these contracts. It is, however, unclear if these individuals are personally from deprived or affluent backgrounds.

References

Anon. Kids back in NHS. Dentistry 2005 November 11. http://www.dentistry.co.uk/news/news_detail.php?id=121 (accessed 12 May 2008).

Anon. Free child dental care 'threat'. BBC News online 2006 February 10. http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/health/4700592.stm (accessed 12 May 2008).

Anon. Health Minister stands by the new contract. Dentistry 2006 January 11. http://www.dentistry.co.uk/news/news_detail.php?id=150 (accessed 12 May 2008).

Matthews R. Your new contract questions answered. Dentistry 2006 March 29. http://www.dentistry.co.uk/news/news_detail.php?id=299 (accessed 12 May 2008).

Department of Health. Commissioning NHS primary care dental services: meeting the NHS operating framework. Objectives. London: Department of Health, 2008.

Department of Health. World class commissioning vision summary. pp 18. London: Department of Health, 2008.

O'Brien M. Children's dental health in the United Kingdom 1993. pp 48. London: HMSO, 1994.

Provart S C, Carmichael C . The relationship between caries, fluoridation and material deprivation in five-year-old children in County Durham. Community Dent Health 1995; 12: 200–203.

Noble M, McLennan D, Wilkinson K et al. The English indices of deprivation 2007. Wetherby, Yorkshire, UK: Communities and Local Government Publications, 2008.

North East Regional Information Partnership. State of the region 2008. Newcastle: North East Information Partnership, 2008.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Chris Burke and his team at the Business Services Agency for preparing the data, to Louise Unsworth for support with the data analysis and to Barbara Bramwell for typing the script.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Refereed paper

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Landes, D., Jardine, C. Are restrictive NHS contracts of benefit in addressing health inequalities? An ecological evaluation of their value in the North East of England. Br Dent J 207, E16 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.2009.857

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.2009.857