Key Points

-

Besides dento-legal documentation, dental photography has a host of applications for all dental disciplines.

-

Communication with patients, technicians and specialists is enhanced with dental imagery and photography is a vital tool for educating patients, staff and colleagues.

-

Pictures of treatment carried out at the practice can be used for compiling portfolios for marketing, and for construction of a practice website.

Abstract

Although the primary purpose of using digital photography in dentistry is for recording various aspects of clinical information in the oral cavity, other benefits also accrue. Detailed here are the uses of digital images for dento-legal documentation, education, communication with patients, dental team members and colleagues and for portfolios, and marketing. These uses enhance the status of a dental practice and improve delivery of care to patients.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The primary purpose of digital dental photography is recording, with fidelity, the clinical manifestations of the oral cavity. As a spin-off, secondary uses include dento-legal documentation, education, communication, portfolios and marketing. Each of these uses enhances and elevates the status of a dental practice as well as improving delivery of care to patients.

Whether the use of dental photography is solely for documentation or for other purposes, before taking any pictures it is essential to obtain written consent for permission and retain confidentiality. Unless the patient has unusual or defining features such as diastemae, rotations etc, it is difficult for a layman to identify an individual by most intra-oral images, and hence confidentiality is rarely compromised. However, extra-oral images, especially full facial shots, can and do compromise confidentiality and unless prior permission is sought, these types of images should not be undertaken. This is also applicable for dento-facial images that include the teeth, lips and smiles, which are often unique and reveal the identity of patients. A standard release form stating the intended use of the pictures can readily be drawn up, and when signed by the patient, should be retained in the dental records (Fig. 1). A crucial point worth remembering is clearly stating the 'intended use' of the images. While most patients will not object to dental documentation for the purpose of recording pathology and treatment progress, they may be more reticent if their images are used for marketing, such as on practice brochures or newsletters for distribution by a mailshot.

Dental documentation

Dental images, similarly to radiographs or other imaging such as CT scans, become part of the dental records and should be respected accordingly (Fig. 2). Nowadays many media are available for image display and storage including prints, computer hard drives, discs and memory cards or other back-up devices (Fig. 3). While this plethora of methods allows flexibility and convenience, it also demands added responsibility for ensuring that discs or memory cards do not go astray. Each medium has its advantages and limitations. A printed photograph is ideal for educating patients about a specific treatment modality, or for showing the current state of their dentition and subsequent improvement after therapy. However, prints are not a good method for archiving. On the other hand, electronic storage is preferred for permanent archiving and retrieval as it is environmentally friendlier, but is more cumbersome and not readily available to hand compared to prints. The chosen medium is a personal preference and varies for each practice. Fully computerised surgeries may opt to store patients' images with their dental treatment details, while paper-based surgeries may prefer photographic prints for easier access.

Dental documentation can be divided into the following categories:

-

1

Examination, diagnosis, treatment planning

-

2

Progress and monitoring

-

3

Treatment outcomes.

It is worth remembering the proverbial adage, 'a picture really is worth more than a thousand words', especially if one has to type them.

Examination, diagnosis, treatment planning

The first use of photographic documentation is examination, diagnosis and treatment planning, since often during an initial examination, many items are missed or overlooked. Therefore, photography is an ideal method for analysing the pre-operative dental status at a later date. Dental photography should be regarded as a diagnostic tool, similar to radiographs, study casts or other investigations and tests. A series of pre-operative images is not only helpful for recording a baseline of oral health, but is invaluable for arriving at a firm diagnosis and offering treatment options to restore health, function and aesthetics (Fig. 4).

Recording pathology is also a valuable reason, but a photographic record also serves a constructive purpose for many other disciplines, for example analysing facial profiles and tooth alignment for orthodontics, assessing occlusal disharmonies, deciding methods of prosthetic rehabilitation for restoring tooth wear, and observing gingival health and periodontal pocketing or ridge morphology prior to implant placement, to name a few (Figs 5, 6, 7, 8). In the field of forensic dentistry, photographic documentation is an essential piece of evidence. Similarly, taking pictures for suspected cases of child abuse is also indispensable proof.

Progress and monitoring

The second use of documentation is for monitoring the progress of pathological lesions or the stages of prescribed dental treatment. It is obviously essential to monitor progress of soft tissue lesions to ensure that healing is progressing according to plan. If a lesion is not responding with a specific modality, assessment can be useful for early intervention with alternative treatment options rather than waiting for protracted intervals that could exacerbate the condition. Other uses include tooth movement with orthodontic appliances, gingival health after periodontal or prosthetic treatment and soft tissue healing and integration following surgery or gingival grafts (Figs 9, 10). Visual documentation also emphasises to patients the need for compliance to regain oral health, eg adhering to oral hygiene regimes or dietary recommendations.

Treatment outcomes

Besides achieving health and function, which are relatively objective goals, the outcome of elective treatments such as cosmetic and aesthetic dentistry is highly subjective. Aesthetic dentistry is one of the major branches of dentistry that can produce ambivalent results. In these instances, if dental photography is not routinely used as part of the course of treatment, it is a recipe for disaster and possible future litigation. Accurate and ongoing documentation is a prerequisite for ensuring that the patient, at the outset, understands the limitations of a particular aesthetic procedure. In addition, if the patient chooses an option with dubious prognosis, or against clinical advice, photographic documentation is a convincing defence in court.

Communication

Patient

Most patients are not dentally knowledgeable and will benefit from explanations of various dental diseases, their aetiology, prevention and amelioration. A verbal explanation alone may be confusing or even daunting for a non-professional, but when a pictorial representation is included it can be elucidating and has a lasting impact. For example, many individuals suffer from some form of periodontal disease and showing pictures ranging from mild gingivitis to refractory periodontitis leaves an ever-lasting impression, informing the patient of the potential hazards of this insidious disease (Figs 11, 12, 13, 14, 15). In addition, most patients are oblivious to advances in dental care, for example all-ceramic life-like crowns or implants to replace missing teeth. Once again, a visual presentation is invaluable so that the patient can judge the benefits, as well as pitfalls of these relatively novel treatment options (Figs 16, 17, 18). Furthermore, before informed consent can be obtained, the patient needs to be presented with treatment options, together with advantages and disadvantages of each proposed modality.

The patient in Figure 13 after scaling and polishing teeth

The presentation of case studies can be as simple as showing pictures, either prints or on a computer monitor, or using advanced methods such as software manipulation and simulation of what is achievable with contemporary dental therapy. If software manipulation is used, showing virtual changes, say to a smile, it is important to emphasise to the patient that the manipulation is only for illustrative purposes and what is seen on a monitor screen may not be possible in the mouth. Also, giving 'before' and 'after' software simulations should be resisted, as these become a legal document that the recipient may refer to if the outcome is not as depicted in the images.

Staff

In a similar vein to patients, the entire dental team can also benefit from seeing treatment sequences, and be better prepared to answer patient queries. Furthermore, new staff can appreciate the protocols involved in complex restorative procedures, while existing members can learn about new techniques based on the latest scientific breakthroughs before they are incorporated into daily practice. Dental education is invaluable for staff members to play their roles within a team and stresses their responsibilities for effective communication, cross infection control and keeping abreast of changing ideas and paradigm shifts.

Academic

Beyond patient and staff education, photography is an integral part of lecturing for those wishing to pursue the path of academia (Fig. 19). In addition, if a clinician desires to publish postgraduate books or articles, either now or in the future, meticulous photographic documentation is a must. There are innumerable publications ranging from high-level academia to anecdotal dental journal. Whichever appeals to an individual is a personal choice, but having a practice or dentist profiled or published in the dental literature adds kudos to a practice (Fig. 20). Also, local newspaper features are reassuring for existing patients and promote the surgery to potential new clients.

Specialists

If referral to a specialist is necessary, either for further treatment or a second opinion, attaching a picture of the lesion or pre-operative status is extremely helpful. This saves time trying to articulate findings of a visual examination and also allows the specialist to prioritise appointments, particularly in cases of suspected pre-cancerous or malignant lesions. Alternately, the images can also be relayed via email attachments, a CD or DVD.

Dental technician

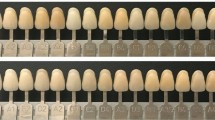

Communication is also vital between clinician, patient and dental technician. This is particularly relevant to aesthetic dentistry, which can be trying for all concerned. As previously mentioned, aesthetics is not a clear-cut concept. Therefore, if patients' wishes are not effectively conveyed to the ceramicist, who after all is making the prostheses, disappointment is inevitable. The best way to mitigate this eventuality is by forwarding images of all stages of treatment to the ceramicist, together with the patients' expectations and wishes. Photographs can be traced, or marked with indelible pens to communicate salient features such as shape, alignment, characterisations, regions of translucency or defining features such as mamelons, banding, calcification, etc. Also, taking pictures at the try-in stage allows the ceramist to visualise the prosthesis in situ in relation to soft tissues and neighbouring teeth, as well as to the lips and face. At this stage, alterations can change the shape, colour, alignment, etc, before fitting the restoration (Fig. 21), which obviously avoids the post-operative dissatisfaction that can be embarrassing, frustrating and costly if a remake is the only reparative option.

Portfolios

Building a practice portfolio of clinical case studies is time consuming but well worth the effort. Some uses have already been mentioned, such as education, and others, eg marketing, are discussed below. The purpose of showing clinical photographs to patients is twofold: firstly, education about a particular dental treatment option and secondly, convincing sceptics about dental care, or ambivalent patients regarding choice of practices that can deliver a proposed treatment plan. While explanations accompanied by pictures and illustrations from dental journals and books are satisfactory for educating patients, they are not convincing evidence as to whether or not a clinician can deliver what is shown in the textbooks. However, pictures taken of patients at the practice who have been successfully treated carry credence and support claims for performing a specific procedure.

A useful starting point is collating sequences of different dental restorations, eg crowns or implants. Over a period of time, examples of every treatment carried out at a practice can be documented and subsequently used for educating patients, informing them of the benefits and pitfalls of a given therapy. A verbal explanation, of say implants, may be inadequate for patients to fully appreciate the time and effort necessary for achieving successful results. But a visual clinical sequence explains the complexities of advanced treatments, and also helps to justify the expenses involved. After suitable training, educating patients can be delegated to another member of the dental team, eg a nurse, hygienist or therapist, who can use the clinical case studies to accompany verbal explanations.

The method of presenting photographs is varied, including using prints or a computer monitor. If prints are chosen, they should be printed on high quality photographic paper, either by a photographic laboratory or an inkjet colour printer. An album or folder with separators, similar to a family album, is ideal for displaying different treatment sequences. An album is also an excellent coffee table book, which can be placed in the waiting room for patients to browse through. Using the digital option for presentation is more elaborate and stylish. The simplest is an electronic or digital picture frame (Fig. 22) loaded with a series of repeating pictures, which can be manually advanced while talking through a modality, or set to automatic transitions if placed in a waiting room or reception area. The most sophisticated option for creating a digital portfolio is using presentation software, eg Microsoft® PowerPoint™. This software allows greater flexibility compared to advancing from one image to the next. As well as adding text, visual effects and animations, sound or music can be included to enhance the presentation, making the whole educational experience memorable and exciting. Once prepared, the presentation can either be manually advanced for one-to-one sessions, or set to automatic display and placed in a communal area of the practice (Fig. 23).

Marketing

The last, and an important use of dental photography, is for marketing purposes. Before embarking on any form of advertising it is advisable to consult the GDC guidelines, and preferably have items checked by an indemnity organisation to ensure adherence to ethical and professional standards. Many stock images of teeth and dental practise can be obtained from a dental library or as Internet downloads. But as previously mentioned, using clinical pictures of practice patients enhances confidence for those who are ambivalent about which practice to attend. It also elevates the practice reputation by picturing a welcoming dental team, or showing treatment carried out at the practice.

Marketing can be divided into internal and external categories. The former includes all forms of stationery, practice brochures and newsletters, while latter includes newspapers, journals, books or web pages.

Internal marketing

A variety of stationery can benefit from depicting beautiful smiles of bright, clean and healthy teeth. Many dental practices incorporate pictures of teeth or smiles in their logos and with artistic creativity these can be unique and defining trademarks. Examples of stationery include letterheads, appointment cards, estimate forms, post-operative instructions and business cards (Figs 24, 25). In addition, practice merchandising such as customised toothbrushes, ball point pens, pads, bags or other gift items are another form of marketing that can incorporate practice logos.

A major piece of practice literature which lends itself to imagery is the practice brochure, leaflet or newsletter (Fig. 26). The choice of images is a matter of personal taste and can include pictures of the outdoor view of the premises, reception area, treatment and sterility rooms, gardens or even a patio waiting area for the summer months. It is always more welcoming if each of the practice views includes a smiling staff member, rather than an empty room, which is perceived as isolated, cold or an advertisement for dental surgery equipment or furniture. Other ideas are showing the entire practice team or faces of individual dental personnel. Clinical images of 'before' and 'after' pretty smiling faces are also always useful inclusions, or sequences showing stages of particular treatments such as crowns, fillings and implants. If clinical images are included, it is important to avoid imagery that is gruesome or off-putting to a layman. Images of surgical procedures, inflammation or haemorrhage are a few examples that obviously warrant exclusion.

Designing a practice brochure can either be assigned to a graphics company, or done in-house using numerous drawing software packages. The market is awash with drawing and photo-editing software of varying complexity that can be utilised to create a bespoke brochure or newsletter. Many software packages have standard templates for a variety of stationery, which is relatively easily tailored by adding text and images. Some popular designing and graphic software are Adobe® Creative Suite, Corel Draw®, Quark® Xpress, Pages and many word-processing software packages, eg Microsoft® Word. All these applications have ready-made templates and once the designing is finished, the files can be transferred to a printing house via email, CD or memory stick for proofing and a subsequent print run. Chapter 10 in the series details the stages involved in designing a practice brochure.

External marketing

Before the advent of the Internet, advertising in telephone directories, local newspapers, or even radio and television were the ideal channels. While these media are not obsolete, probably the most effective method today of getting a message across to a large audience is by using the Internet. More and more households and businesses have access to the Internet, and using search engines such as Yahoo® or Google® is quicker than wading through heavy telephone directories.

If one is computer literate, it is relatively easy to design an in-house web page, using images similar to that on the practice brochure or newsletter. However, to construct a web page with an impressive design layout with slick transitions and music requires employing a professional web designer. In addition, the web page designer can advise on the best methods for obtaining hits for the site, plus a host of additional features (eg links) that ensures the investment is productive. Although the initial cost may seem excessive, it is well worth investing in this form of advertising as it is without doubt the future, and the capital outlay can be readily recouped within a short period of time by referrals and/or new patients.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Refereed paper

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Ahmad, I. Digital dental photography. Part 2: purposes and uses. Br Dent J 206, 459–464 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.2009.366

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.2009.366

This article is cited by

-

Evaluation of smartphone dental photography in aesthetic analysis

British Dental Journal (2021)

-

Factors associated with gagging during radiographic and intraoral photographic examinations in 4–12-year-old children

European Archives of Paediatric Dentistry (2021)

-

Characteristics of dental note taking: a material based themed analysis of Swedish dental students

BMC Medical Education (2020)

-

Colour fidelity: the camera never lies - or does it?

British Dental Journal (2020)

-

Digital dental photography. Part 10: printing, publishing and presentations

British Dental Journal (2009)