Key Points

-

Informs the reader about the role of dental access centres (DACs).

-

Identifies that DACs and 'high street' dentists serve different populations.

-

Raises questions about the benefits of DACs.

-

Offers suggestions for the development of the new primary dental care contract.

Abstract

Introduction Dental access centres (DACs) were introduced in England at the turn of the twenty-first century in response to a growing problem of access to NHS dental services. DACs were expected to offer NHS dental care primarily to those patients that were unwilling or unable to attend 'high street' dental practice. At the same time, the new NHS primary care dental contract in England, introduced in April 2006, has been associated in some areas with access difficulties, with routine dental patients having difficulty accessing NHS dental care. In light of these changes, have DACs become an alternative provider of NHS dental services to patients seeking routine dental care?

Method In summer 2007, a cross sectional dental epidemiological study was undertaken in Halton & St Helens PCT and Warrington PCT to compare the dental health and attitudes to dental visiting of adult patients attending DACs and neighbouring 'high street' dental practices.

Results The results of the study showed that DAC patients: were younger and from a more disadvantaged background than patients attending 'high street' practices; had worse oral health than 'high street' dental patients; experienced more frequent episodes of dental pain than 'high street' dental patients and were more likely to be dentally anxious; had different attitudes to dental health than their 'high street' counterparts.

Conclusions The study suggests that the DACs in Halton, St Helens and Warrington are offering treatment to a different population of patients to that seen in neighbouring 'high street' practices and therefore the DACs are fulfilling the function expected of them locally.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The availability of NHS dental care in England diminished throughout the 1990s1 as dentists became increasingly unhappy with the way the traditional NHS framework allowed them to practise.2 In 1999, the Prime Minister pledged that by 2001 everyone in the country would be able once again to see an NHS dentist. In order to help in the delivery of this promise, the Government set up a number of dental access centres (DACs) which were expected to deliver a complete range of NHS dental services, including routine and urgent care to those patients with no tradition of regular visits to dentists. In announcing the introduction of dental access centres on 3 November 2000, Lord Hunt stated that 'some dental access centres will be sited in areas of poor dental health but with no tradition of regular dental visits to dentists, and these centres will work closely with other healthcare professionals to make sure that people who need dental care can get it'.3 By 2001 a total of 50 DACs had been established.

Concurrent with the introduction of DACs, the Government embarked on a wider restructuring programme of NHS primary dental care in England. The publication in 2002 of its Options for change document4 set out a framework for a modern NHS primary dental care service in England that would be shaped by the needs of patients, would be locally responsive and would be focussed on prevention of disease. In April 2006 and in the face of considerable scepticism from the dental profession and NHS managers,5 a new primary care NHS dental contract was introduced in England. Two years on from the introduction of the new contract, the profession remains uncomfortable with it. Fewer patients are being seen within NHS dentistry6 as dentists report continued dissatisfaction with the new contract. The Commission for Public and Patient Involvement in Health (CPPIH) in 2007 claimed in a survey of 750 dentists in England that 84% of participants believed that the new contract made it more difficult for patients to get an NHS dental appointment.7 The CPPIH survey revealed that the new contract offered dentists little incentive to take on new patients, penalising those who needed treatment most. The British Dental Association, giving evidence to a House of Commons Health Committee in February 2008, described the contract as 'driving dentists away from the NHS'.8 The subsequent dental report produced by the House of Commons Health Committee and published in June 20089 identified serious problems with the new dental contract.

The new dental contract had the effect, unintentionally, of encouraging dentists to focus their care on regularly attending patients (for example attendance at a GDP every 6-9 months) whilst denying dental access to new patients who, if they had poor dental health, were perceived as being uneconomically viable. Given that approximately 45% of the adult population in England attend a dentist on an irregular basis,10 it is clear that such an approach by the dental profession has the potential to deny access to dental care to a significant numbers of adults who may well be keen to embark on regular dental attendance within the traditional primary dental care setting, ie 'high street' dental practices.

For those communities with an NHS 'high street' dental access problem the DACs might represent an alternative source of care and the possibility exists that many potentially 'routine' patients, denied regular care with a GDP, would present at the DAC for treatment. If this were the case then the DACs would in effect be seeing and treating patients that traditionally secured care within the 'high street' dental setting. Although dental access centres evolved to meet the needs of local communities and therefore took on a number of different roles, it was never envisaged that their key role was to compete for patients that routinely sought care within the 'high street' setting.

Good dental health is associated with regular dental care and irregular, symptomatic visiting patterns tend to be associated with poor dental health.11 It is likely therefore that those patients choosing in the first instance to attend DACs for their dental treatment rather than 'high street' dental practices would be expected to have worse oral health than those in the community who visited their dentist on a regular basis. If, however, potentially 'routine' NHS dental patients were inadvertently turning to dental access centres because of the lack of availability of 'high street' dentists, they would be expected to have a similar level of oral health to that found amongst same aged adults attending local 'high street' practices.

In order to discover if the DACs were delivering their expected function or alternatively were treating routine patients that were unable to access 'high street' dental services, a study was undertaken in Halton, St Helens, and Warrington PCTs. The aim of the study was to measure the dental health of patients attending DACs and 'high street' dental practices in close proximity. The study also aimed to identify the views that patients in these different dental care settings held about their dental visiting preferences and the reported levels of anxiety patients had about dental care. The results of this study were expected to produce information about the nature of patients attending DACs and 'high street' dental practices situated in close proximity to each other. In turn, this information was expected to inform the future commissioning of local dental services.

Method

The study took place in the summer and autumn of 2007 in Halton and St Helens PCT and Warrington PCTs. All three DACs situated within the PCTs boundaries were included in the study. Three local NHS dental practitioners with multi-surgery practices, situated within one mile of the DAC sites, were selected and invited to participate in the study. Local practices were contacted because they would be expected to draw their patients from the same geographical catchment area as the DACs. The three practices selected for inclusion had the greatest involvement with the host PCTs in terms of commissioning local dental services.

This study was a preliminary assessment of the dental health needs and attitudes of patients attending different clinical settings, and as no hypothesis was being tested, a decision was taken to draw a sample of convenience that was sufficiently large for simple age specific comparisons to be made.

Arrangements were made for an experienced dental epidemiologist to attend the DACs and the practices on selected days. These prearranged visits were designed to cause minimum disruption to the smooth running of the dental sites. On arrival at the surgery sites, the dental epidemiologist invited those patients attending throughout the session to participate in the study. All healthy adult patients aged 18 years and over attending the selected practices and DACs, on the days when the epidemiology team were present, were invited to join the study. The field work was completed within a four month period. Patients who were unable to understand the information detailing the reasons behind the questionnaire or who were unable to provide informed consent were excluded. Patients presenting with severe pain, bleeding or trauma were excluded from the study.

Patients were recruited as they presented at the DACs/dental surgeries to register their attendance with the reception clerk. The needs assessment was explained to patients and positive consent was secured.

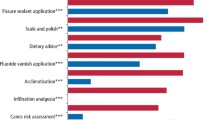

The dental intervention consisted of:

-

Completion of a questionnaire

-

A visual inspection of the teeth using a dental mirror by an experienced trained calibrated dentist.

The recruiting dentist member of the team delivered the questionnaire. The patient was given the option of either completing the questionnaire themselves, or the questionnaire was completed on their behalf by an experienced trained dental nurse who used the verbal answers given by the patient in response to the questions.

A single experienced, trained and calibrated dental epidemiologist conducted all dental examinations in a dental chair and clinical measurements were recorded by a trained dental nurse in the surgery.

-

Each patient had a visual assessment of the presence of debris (supragingival plaque and calculus) on their teeth. This was measured on a visual dichotomous scale: present/not present

-

Each patient had the number of decayed, missing and filled teeth recorded using visual inspection only, supported by the surgery dental light.

The caries clinical examination followed the protocol agreed by the British Society for the Study of Community Dentistry.12 The examination data were collected electronically using a password protected laptop computer and the data were subsequently downloaded onto a secure server in Halton and St Helens PCT in accordance with the PCT policy regarding data protection.

The questionnaire data were completed on paper and inputted to a computer database for analysis. Analysis of the data took place in Halton and St Helens PCT, Manchester University and The Dental Observatory, Preston. The socioeconomic status of the participants was assessed using the Index of Multiple Deprivation (IMD 2007) for the Super Output Area containing the postcode of place of residence.13

Advice from Cheshire and Merseyside Local Ethics Committee was that formal ethical approval was not required for the study, provided positive consent was secured. Support for the study was secured from the Research Governance Departments of the participating Trusts.

Results

Table 1 examines the demographic characteristics and dental health of patients attending DACs and neighbouring 'high street' dental practices. The data show that whilst attendance by gender is similar, DAC attendees tend to be younger. Over half of the patients attending DACs (33, 55.2%) were less than 35-years-old, whilst amongst 'high street' dental patients the figure was 30, 19.1%.

DAC patients were more likely to come from deprived communities and to be exempt from dental charges. The mean IMD score for DAC patients was 38.8 whilst the comparable figure for 'high street' patients was 23.3. Almost half of DAC patients were exempt from charges, whilst the figure was one in seven for 'high street' dental patients.

There were differences in smoking habits between the two study groups. Reported smoking was three times more prevalent amongst DAC patients than amongst those attending 'high street' dentists (60.3%, 19.1% p <0.001).

The dental health differences between the two study groups were marked. More DAC patients presented with caries (79.3%, 33.8% p <0.001). The mean level of active decay (mean DT) was significantly greater amongst DAC patients (3.2, 0.94 p <0.001). The prevalence of plaque (69.0%, 33.5% p <0.001) and calculus (67.2%, 40.6% p <0.01) were both significantly greater amongst DAC patients. In addition to having poorer oral health than their 'high street' dental patient counterparts, DAC patients were also more likely to be fairly or very anxious about the prospect of dental treatment (50.0%, 17.8% p <0.001).

Table 2 examines the self reported dental service use and attitudes held by DAC and 'high street' dental patients. DAC patients were more likely to attend a dentist when in pain than their 'high street' dental patient counterparts (48.3%, 12.7% p <0.01); were less likely to view regular attendance as important (25.9%, 45.9% p <0.001); were more likely to be indifferent about seeing the same dentist on a regular basis (53.4%, 80.9% p <0.001) and were less likely to rate their own dental health as being good (15.5%, 42.7% p < 0.01).

DAC patients are twice as likely to have experienced toothache in the previous 12 months (67.2%, 31.4% p <0.01) and are less likely to have reported visiting a dentist within the last year (44.8%, 93.6% p <0.01).

Table 3 sets out the results of a multiple logistic regression analysis with attendance at a DAC or GDP as the dependent variable. The data show that adults from disadvantaged backgrounds, younger adults, adults with active disease, adults with a preference for symptomatic attendance and adults exempt from patient charges were more likely to attend a DAC than a 'high street' dentist. These variables were significantly and independently associated with attendance at a DAC.

Discussion

Dental Access Centres (DACs) were set up in haste as a political response to a perceived access problem and many were expected to see and treat those members of the local community that did not wish to attend 'high street' dentists on a regular basis. There was an expectation that the patients attending DACs would have limited interest in their own dental health, would have high levels of dental disease and would be likely to be disinterested in regular dental attendance. This study suggests that in the two PCTs of Halton and St Helens and Warrington, the DACs do attract a different subset of the population to dentists working in the 'high street' dental practices in close proximity. The results of this study do not suggest that the DACs are treating patients whose natural dental home is the 'high street'.

There is little scientific literature available on the impact of DACs on the delivery of primary care and it should be recognised that this study is limited in scope and may not be a true reflection of the wider 'population' of DAC services. Nevertheless, generally, DAC patients in this study tended to be younger than their counterparts attending 'high street' dental surgeries and they also tended to come from more disadvantaged localities and to be exempt from patient charges.

As far as comparative dental health is concerned, the dental health of DAC patients is substantially poorer than that of adults attending 'high street' dentists with DAC patients more likely to have decayed and unsound teeth. The levels of oral cleanliness amongst the study participants reflect the patterns of dental decay. DAC patients are more likely to have visible plaque and supragingival calculus than patients attending 'high street' dentists. DAC patients are also three times more likely to be smokers than 'high street' dental patients.

The attitudes towards dental treatment also vary considerably between the two study groups. DAC patients are more likely to prefer symptomatic attendance. They view regular dental attendance as less of a priority than 'high street' dental patients and therefore are less likely to attend a dentist regularly. They are more likely to experience toothache, less likely to consider their dental health as being 'good', and are somewhat indifferent to whether or not they are treated by the same dentist. DAC patients are also more likely to be anxious about the prospect of dental treatment than are 'high street' dental patients.

What does this information tell planners of dental services? Firstly it is clear that patients attending DACs are quite different to patients attending 'high street' dental practices. They tend to be younger, more socially disadvantaged, their dental health is worse, they are anxious about dental treatment and they are less committed to regular dental treatment. Given these observations, is a DAC the most appropriate setting to treat such patients?

It could be argued that providing a setting for intermittent dental care is a sensible approach for those disinterested in long term dental treatment. In the DACs, patients are able to have their immediate symptoms dealt with and are not pressurised into developing a long term professional relationship with a dentist. There is no underlying expectation that patients will necessarily return for multiple repeat visits involving extensive dental intervention. There is no remit within the DAC to establish long term dental behaviour change amongst patients that attend.

The counter argument is that patients attending DACs are being offered dental care outside the mainstream NHS primary dental care services and as such they are not exposed to the benefits that come from having a long term professional relationship with a dentist ie the development of stable dental health based on a preventive approach. By attending a DAC, patients are potentially missing an opportunity to access mainstream NHS dental care services, where long term care is encouraged. The data from this study suggest that DAC patients experience frequent episodes of pain, indicating that the immediate dental care offered by the DAC is of limited long term benefit. If these young, anxious patients with significant dental needs are to be 'rehabilitated' the most likely setting for this will be 'high street' dental practice, unless the DACs adopt a more long term approach to the care they offer.

In order for dentists in the 'high street' to accommodate the stereotypical DAC patient, there is a need for a change in the way NHS dental care is delivered within the new dental contract. New patients arriving at a dental practice pose a considerable challenge for dentists, particularly if those patients are anxious and have high levels of dental disease. Currently dentists perceive these patients as problematic because under the terms of the new dental contract, dentists believe that they are expected to offer a comprehensive 'repair' service that renders such patients dentally fit. This intensive and extensive rehabilitation approach is often not in the interests of either the patient or the dentist. The patients may find the demands of extensive dental treatment a daunting experience and if they are anxious, such an approach may well be counterproductive. As for the dentists, the considerable time and effort required to make these patients dentally 'fit', that is, put right years of dental neglect, is not reflected in the remuneration or credit they receive.

A more holistic approach is called for. Anxious patients with high levels of dental disease should be offered structured incremental dental care within the 'high street' dental setting. Early visits should include relief of pain and the establishment of effective prevention. It may be that the first 'course' of treatment stops at this point to allow dentist and patient to assess progress and commitment. Subsequent courses of treatment may include more complex restorative care as confidence and commitment grow. By treating new patients in this way, within the 'high street' dental setting, there is an opportunity for their conversion from anxious irregular symptomatic attender with poor oral health to confident asymptomatic attender with good and stable oral health. During the transition phase, which may take months or years, the patient's dental health can be expected to gradually improve, however, during this phase the patient will not be dentally fit in the accepted sense. This transitional phase should be seen as quite acceptable. Further, patients that are not exempt from NHS dental charges will be expected to pay the appropriate fees for each 'transitional' course of treatment.

The new NHS dental contract is a contract between PCTs and local dentists. Provided that PCTs are satisfied that the best interests of patients are being met by the approach outlined above, then there should be no obstacles to local contracts being drawn up that capture this holistic dental care plan for those in the community with some of the greatest dental needs.

Planners now need to consider the role of the Dental Access Centre. They were set up in response to a dental access problem at a time when legislative barriers offered PCTs limited scope to engage innovatively with the dental profession. At the time of writing, in 2008, the position is very different. PCTs are now in a robust contractual relationship with NHS dentists and the opportunity exists for changes in the way dental services are delivered. The Department of Health Operating Framework 2008, which was associated with an injection of new monies for primary care dentistry, has set new patient access targets for 'high street' dentists. More recently, the Department of Health, in its document The next stage review: our vision for primary and community care, has called for integration and remodelling of primary health care services in order to offer patients choice and quality care.14 In light of these developments does the DAC have a clear role? Should they exist so that patients seeking symptomatic care have a choice of dental setting? Should they act as a signposting service, or halfway house, for those patients seeking a route into mainstream primary dental care? Should they be developed to deliver complementary services to 'high street' dentists? Should the DACs be closed down? Clearly the opportunity exists for local dentists and PCTs to work together in the creation of a new DAC services tailored to local needs and demands. The new dental contract offers dentists and PCTs the freedom to change the way primary dental care is delivered and DACs must take their place in the change that is taking place.

Conclusions

-

Patients attending DACs have poor dental health by comparison with patients attending 'high street' dental practices

-

DACs may not be the optimal setting for treating patients with significant dental needs

-

The new NHS dental contract allows PCTs to create positive environments in which adults with high levels of dental need can be cared for holistically

-

The role of Dental Access Centres needs to be reviewed.

References

Harris R . Access to NHS dentistry in South Cheshire: a follow up of people using telephone helplines to obtain dental care. Br Dent J 2003; 195: 457–461.

Pitts N B . NHS dentistry: options for change in context – a personal overview of a landmark document and what it could mean for the future of dental services. Br Dent J 2003; 195: 631–635.

Lord Hunt. http://www.dh.gov.uk/en/Publicationsandstatistics/Pressreleases 2000.

Department of Health. NHS dentistry: options for change. London: Department of Health, 2002.

Milsom K M, Tickle M, Threlfall A, Pine K et al. The introduction of the new dental contract in England – a baseline qualitative assessment. Br Dent J 2008; 204: 59–62.

Fewer seen by NHS dentists, government statistics reveal. Br Dent J 2008; 204: 288.

Campaign highlights dentistry access problems in England. Br Dent J 2007; 203: 502.

Dental contract driving dentists from NHS, select committee told. Br Dent J 2008; 204: 230.

House of Commons Health Committee. Dental Services. Fifth Report of Session 2007-08, Volume 1. London: The Stationery Office.

The NHS Information Centre. http://www.ic.nhs.uk.

Adult Dental Health Survey. Oral health in the United Kingdom. London: The Stationery Office 1998.

Pine C M, Pitts N B, Nugent Z J . British Association for the Study of Community Dentistry (BASCD) Guidance on the Statistical Aspects of Training and Calibration of Examiners for Surveys of Child Dental Health. Community Dent Health 1997; 14 suppl 1: 18–29.

Department of Communities and Local Government, Indices of Deprivation, Crown Copyright 2007.

Department of Health. The next stage review: our vision for primary and community care. London: Department of Health, 2008.

Acknowledgements

This study was commissioned by Halton and St Helens PCT and Warrington PCT. The fieldwork was coordinated by Mrs Clare Jones and Mrs Paula Kearney-Mitchell, Dental Public Health Co-ordinator, Halton and St Helens PCT. The study team wish to thank the dental practitioners who supported this study: Mr David Sparke, Dr David Tildsley, Mr Chris Williams and also Dental Access Centre staff.

The team also wish to thank the dental public health staff within Halton and St Helens PCT and the Dental Observatory, Preston who contributed to the study.

Finally, the study team wish to thank those patients that participated in the project.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Refereed paper

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Milsom, K., Jones, C., Kearney-Mitchell, P. et al. A comparative needs assessment of the dental health of adults attending dental access centres and general dental practices in Halton & St Helens and Warrington PCTs 2007. Br Dent J 206, 257–261 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.2009.165

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.2009.165

This article is cited by

-

Behavioural intervention to promote the uptake of planned care in urgent dental care attenders: study protocol for the RETURN randomised controlled trial

Trials (2022)

-

Clinical and academic recommendations for primary dental care prosthodontics

British Dental Journal (2019)

-

Assessing the efficacy and social acceptability of using hygienist-therapists as front-line clinicians

BDJ Team (2017)

-

Validity and reliability of remote dental screening by different oral health professionals using a store-and-forward telehealth model

British Dental Journal (2016)

-

Feasibility study: assessing the efficacy and social acceptability of using dental hygienist-therapists as front-line clinicians

British Dental Journal (2016)