Key Points

-

Dentists do not appear to be any more stressed than they were prior to the introduction of the new dental contract.

-

Dental practice can cause stress but stress can be positive.

-

Use and abuse of alcohol within the profession does not appear to be a major problem.

-

Greater awareness of the role of occupational health services may be helpful to many dentists.

Abstract

Objective To record stress levels and self-perceived health and health-related behaviours of dentists.

Design and Method A questionnaire was sent to a random sample of 1,000 BDA members in April 2005. Respondents were questioned about self-perceived general health, medicine and drug use, tobacco and alcohol use, self-perceived general well-being, sexual health, occupational health, physical activity and nutrition. There were also some questions about women's health. Results were compared to a BDA study of dental professionals' health and well-being carried out in 1996.

Results A response rate of 55% was achieved (545 replies). Two-thirds (67%) of respondents considered themselves in very good or excellent health and 53% were happy and interested in life. Only 42% were free from pain and discomfort and 26% experienced levels of pain that prevented them from taking part in a few or some activities. The majority (86%) had very or fairly stressful lives but most (83%) were either very or somewhat satisfied with their lives. Nearly all respondents (90%) planned to take action to improve their health during the 12 months following the survey: popular actions planned included increasing exercise (58%) and losing weight (42%). Very few respondents used tobacco (4% daily and 4% occasionally) and most (59%) said that only a few of their friends smoked: 36% had no tobacco-using friends. Only 3% of respondents had never had alcohol. The Short Michigan alcohol screening test revealed that 6% of dentists had a drink problem and 9% had alcoholic tendencies. The most common factors contributing to stress at work were patient demands (75%), practice management/staff issues (56%), fear of complaints/litigation (54%) and non-clinical paperwork (54%). More than half (53%) of respondents were relatively inactive during the day but 57% took some form of physical exercise at least 3-4 times per week. Nearly half (49%) of respondents felt that their level of physical activity was very likely or somewhat likely to cause them health problems.

Conclusion In spite of the dramatic recent changes to dentistry, the differences between the results of this study and the results of the research carried out in 1996 are minimal. Claims that dentistry is a dangerously stressful occupation are not justified and dentists seem to be as well and happy as other professional groups. There is however, a slight increase in the use of alcohol. Stress management and personal and professional awareness training should be included in the undergraduate curriculum, so that threats to physical and mental well-being which might occur during a dentist's professional life may be avoided or addressed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Evidence suggests that working in dentistry can be detrimental to the long-term health and general well-being of an individual, due to the mentally and physically challenging nature of the profession.1,2 Dental practitioners often work alone and this, coupled with the strain of simultaneously running a business and providing a high standard of clinical care to patients, can be psychologically stressful.3 Dealing with nervous or anxious patients can be emotionally challenging and is another source of stress. The dental surgery is a difficult physical working environment and dental practitioners are often required to sit for long periods of time in awkward positions, whilst undertaking extremely fine and exacting work.4

In 1987, a study of job satisfaction, mental health and job stressors identified factors which caused stress in general dental practitioners (GDPs) in the UK.5 A follow-up study carried out ten years later highlighted new stressors affecting GDPs, which included uncertainty felt during times of change.6 In addition, a recent study of stress and health in UK GDPs showed that a high percentage of NHS dentistry was associated with high levels of overall stress.7

A study of dental professionals' health and well-being was carried out by the BDA in 1996 and the results were published in 1997.8 The results indicated that dental personnel were probably as healthy and well as any other professional subgroup of the population and the anecdotal evidence about stress levels in dentistry causing emotional and physical damage did not appear to be borne out. However, many respondents had fairly or very stressful lives and more than half described themselves as being in some degree of pain. Drug use and smoking were relatively unproblematic in the 1996 sample, but binge drinking of alcohol and worries and concerns about drinking were surprisingly common. More recently, high levels of stress were reported among GDPs in Dorset and Somerset.9 The study showed that although the majority of dentists are well and happy, many do have health and welfare problems, so the BDA has in recent years been working to ensure that appropriate occupational health services are available to support dental practitioners.

Since January 2004, annual funding has been provided by the Government to enable all primary care trusts (PCTs) in England to commission occupational health services for the dental team.10,11 However, in many areas appropriate services have still not been commissioned and this is an issue which should be addressed. Examples of services which could be useful for dentists and their teams include:

-

Immediate (24 hour) access to advice and treatment for blood exposures, including HIV

-

Advice on compliance with Health and Safety and Disability Discrimination legislation

-

Advice on formulation of Health and Safety policies, practices and procedures

-

Assistance in controlling sickness absence and its costs

-

Help with reviewing fitness of employees following illness

-

Advice on 'fitness for the job' to help prevent costly mistakes (human and financial)

-

Assessment of risks relating to health of individuals and groups engaged in particular tasks

-

Monitoring of employees' health on an ongoing basis

-

Management of, access to, and delivery of, first aid services

-

Organisation of health promotion activities to help keep the workforce fit

-

Provision of policies and procedures for the management and alleviation of stress

-

Design and provision of programmes to tackle drug and alcohol abuse

-

Assessment of eligibility for long term disability benefits or retirement on health grounds.

In addition, dental staff are required to have vaccinations against Hepatitis B. Some PCTs have systems in place for the provision of staff vaccinations, and such systems should be established nationwide in order to improve access and remove the general confusion over the provision of the vaccination by GPs.

The study described in this paper is a nine-year follow up to the research carried out in 1996. The aim of the study was to record stress levels and self-perceived health and health-related behaviours in dentists in the UK, in order to determine the type and level of occupational health services needed for dental practitioners. It has been shown that change of any sort can increase stress and be damaging to health and general well-being, irrespective of whether the change is construed as beneficial or not.12 At the time this study was carried out, great changes and upheaval were starting to take place within dentistry [Since 1 April 2006, commissioning of primary care dentistry in England and Wales has been the responsibility of primary care trusts (PCTs) and local health boards (LHBs). This is so that the types of dental services provided can be tailored to meet the particular needs of the local population. Services are provided under GDS contracts or PDS agreements. PDS agreements are fixed term and can be limited to a particular range of clinical care or services (eg orthodontics). GDS contracts are normally open ended and the full range of mandatory services must be provided by the contractor] and it was thought that measurement of occupational health at this time would give an indication of the level of benefit or harm brought about by the new arrangements. This paper describes the levels of health and well-being experienced by dentists and looks at how their general health has changed over the last ten years.

Method

The BDA is the professional association representing 22,500 dentists and dental students in the UK. This is roughly two-thirds of all dentists. A questionnaire was sent to a random sample of 1,000 BDA members, nearly all of whom were working in general dental practice. The sample excluded students, retired members and overseas members to minimise non-response bias (as the survey would not be relevant to these groups). The sample was a random sample and was generated from the BDA database using SPSS. Respondents were offered the incentive of entry into a prize draw to win a BDJ Book and were assured that all responses would be anonymous. A personalised letter from Professor Liz Kay, then BDA Scientific Advisor, and Dr John Renshaw, then Chair of the BDA Executive Board, accompanied the survey. The letter outlined what was expected of respondents and explained that the purpose of the research was to investigate stress levels of dentists and gain evidence for the need for occupational health services for dentists. A pre-paid envelope was included for returning completed questionnaires. The first mail out was carried out in April 2005, and was followed by two reminder follow-ups, each including a further copy of the questionnaire and another personalised letter. In addition, an article about the survey was published in the May 2005 issue of bdanews.13 A recent review by the Cochrane Collaboration on improving response rates to postal questionnaires listed many factors which would increase the odds of response. Some of those listed were used in this study, namely prenotification, follow-up contact, providing a second copy of the questionnaire at follow up, monetary and non-monetary incentives, personalised questionnaires and an assurance of confidentiality.14 As there were no reliable measures of occupationally related stress, the questionnaire (a total of 93 questions covering 11 sides of A4 paper) asked respondents about self-perceived general health, self-perceived stress levels, medicine and drug use, tobacco and alcohol use, self-perceived general well-being, sexual health, occupational health, physical activity and nutrition. The survey also included a short section (13 questions) about women's health. A copy of the questionnaire is available on request.

This methodology is similar to that which was used in the 1996 study, in which postal questionnaires were mailed to a random sample of 600 BDA members working in general dental practice. However, in 1996 each sampled member was sent two questionnaires, one for themselves and one to pass on to a non-dentist member of practice staff. The questions in the surveys were identical but the questionnaires were colour-coded so that those filled in by dental support staff could be distinguished from those completed by dentists.

In the 2005 questionnaire, the section on alcohol included a series of questions relating to respondents' drinking during the 12 months preceding the survey. Respondents were asked to answer yes or no to each question and the results were used to carry out the Short McMaster alcohol screening test15 to ascertain the alcoholic tendencies of respondents.

General well-being of respondents was determined using a set of 14 statements describing positive and negative feelings of well-being. Respondents were asked to indicate how often during the past year they had experienced the feelings described in each statement, using a 4-point scale (1 = hardly ever to 4 = most of the time). Before analysis, the results were recoded so that statements indicating positive well-being were scored on an increasing scale (ie 1 = hardly ever to 4 = most of the time), whilst those indicating negative well-being were scored on a decreasing scale (ie 4 = hardly ever to 1 = most of the time). Each respondent was then given a score corresponding to the sum of his or her answers to each of the 14 questions. A score of 14 corresponds to very negative well-being (ie respondent hardly ever has feelings of positive well-being and experiences feelings of negative well-being most of the time) whilst a score of 56 indicates very positive well-being (ie respondent hardly ever has feelings of negative well-being and experiences feelings of positive well-being most of the time). The question (Q53 in the survey) can be seen in Figure 1.

Results

Following one initial mailout and two reminder follow-ups, a 55% response rate was achieved (545 replies). The profile of respondents was comparable to other BDA surveys conducted at a similar time and can be considered representative of BDA membership at that time. Two-thirds (66%) of respondents were male, and half (49%) of respondents were aged between 36 and 49 years. The majority (94%) of respondents were GDPs. Two-thirds (66%) of those working in general dental practice were practice owners and 44% derived more than three-quarters of their income from NHS work. Many of the results given in this paper are compared with the 1996 study. However, as that study involved both GDPs and dental support staff (ie non-dentist members of practice staff), some results are not directly comparable.

Self perceived health and well-being

Two-thirds (67%) of respondents considered themselves to be in very good or excellent health and 53% were happy and interested in life. From Tables 1 and 2 it can be seen that in 1996 a lower proportion (59%) of dentists than in 2005 described themselves as being in very good or excellent health whilst a similar percentage (50%) were happy and interested in life.

Table 3 shows that only 42% of dental practitioners were free from pain and discomfort. This is a greater proportion than in 1996 (37%), but is still less than half of respondents. Also of concern is that the level of pain experienced by 26% of respondents to the 2005 survey prevented them from taking part in a few or some activities, compared with 22% in 1996.

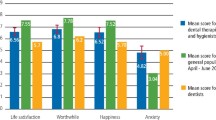

The majority (86%) of dentists had very (21%) or fairly (65%) stressful lives (Fig. 2). These results are similar to those seen in 1996, when 25% considered their lives to be very stressful and 60% fairly stressful.

From Table 4 it can be seen that most (83%) respondents were either very or somewhat satisfied with their lives. This result is almost identical to that seen in 1996, when 84% of GDPs were very or somewhat satisfied.

Nearly all (90%) of the respondents to the 2005 survey planned to take action to improve their health during the 12 months following the survey. As shown in Table 5 and Figure 3, 58% planned to increase exercise and 42% planned to lose weight. Other popular changes planned were improving eating habits (32%) and dealing with stress better (30%). Less than a fifth (18%) of respondents planned to drink less alcohol.

Medicine and drugs

Respondents were asked to indicate which of a list of medicines and drugs they had taken in the four weeks preceding the survey. During this time, 39% had taken pain killers, 13% had taken vitamins and 9% had taken allergy medicines or antihistamines. Table 6 shows the percentage of respondents taking each medicine, drug, remedy or vitamin listed in the questionnaire. These results are not directly comparable to the 1996 survey as the results for that study were for dentists and dental support staff. However, it is worth noting that in 1996 59% of dental staff (ie dentists and dental support staff) had taken painkillers in the four weeks prior to the study. This is a greater proportion than the 39% of dentists in 2005.

Tobacco

Only a very small number of respondents reported using tobacco at all: 4% (22) used tobacco daily and 4% (20) occasionally. In 1996 12% of GDPs smoked. Most (15) of the 22 daily tobacco users who responded to the 2005 survey began using tobacco daily when they were under the age of 21 and the majority (16 of the 22) used tobacco ten times or fewer each day. Nearly all the daily tobacco users (19 of the 22) thought that their habit was very likely or somewhat likely to cause health problems (compared with 74% of smokers in 1996) and ten had tried to quit in the year preceding the 2005 survey. A much larger number of dentists (95 in total) had used tobacco daily in the past – the majority (92%) had started this use before the age of 21 and about half (51%) had given up by the age of 30. Most (59%) of the respondents to the 2005 survey said that only a few of their friends smoked and 36% had no tobacco-using friends.

Alcohol

The 2005 results indicated that only 3% of dentists had never had alcohol. Table 7a shows that nearly half (47%) of those who currently drink alcohol admitted to having regularly drunk more than 14 units per week at some time and the same percentage had regularly drunk more than 21 units per week. Nearly a third (32%) of women had regularly drunk more than 14 units per week, whilst 58% of men had regularly drunk more than 21 units per week. As can be seen from Table 7b, nearly half (48%) of respondents drank six or more units more than once a month whilst 30% drank eight or more units this often. More than a third (35%) of women drank six or more units more than once a month and 38% of men drank eight or more units this often.

The Short Michigan alcohol screening test15 revealed that 6% of dentists had a drink problem and 9% had alcoholic tendencies. In 1996 this test showed that 5% of GDPs had a drink problem and 5% had alcoholic tendencies – considerably fewer than in 2005. In the 1996 study the other questions related to alcohol were worded differently so direct comparisons are not possible, but the results of the 1996 study showed that 5% of GDPs had at some time in the past drunk more than 12 units in a week, 8% had drunk on a daily basis in past year and 36% had consumed more than ten drinks on a single occasion in the past year.

The majority (69%) of dentists started drinking between the ages of 16 and 18 and nearly a fifth (19%) had their first alcoholic beverage when they were aged 15 years or under. Most (88%) respondents thought that it was somewhat or very unlikely that their drinking would lead to health problems and the majority (89%) said that either a few or none of their friend would say they drank too much. Only 28% had tried to reduce the amount they drank over the past 12 months.

Respondents were asked to indicate how many units they had drunk on each day in the week preceding the survey. As shown in Figure 4, the results indicated that alcohol consumption increases through the week. On Monday and Tuesday the majority (66% and 64% respectively) of respondents had no alcohol. However, by Friday this had decreased to 30% and on Saturday only 22% of respondents had no alcohol and 28% drank five or more units. The maximum number of units consumed by respondents on a Friday or Saturday night was 30.

Family and friends

There seemed to be no major family problems for respondents to the 2005 survey. Only 6% reported that they had no relatives that they felt close to (the same proportion as in 1996). Nearly two-thirds (64%) had between one and five relatives they felt close to and 30% had six or more relatives they felt close to. More than three-quarters (76%) of respondents had children (compared with only 53% in 1996) and most (70%) were very satisfied with their relationship with their children. The majority (88%) were married or cohabiting (compared with 73% in 1996) and 70% were very satisfied with their relationship with their partner.

More than half (56%) of respondents had between one and five close friends and 40% had six or more close friends (the questionnaire defined a close friend as someone respondents felt at ease with, could talk to about private matters and could call upon for help). The survey indicated that the majority (77%) of dentists were somewhat or very satisfied with their social life. During the 12 months preceding the survey, 57% of respondents saw a close friend once a week or more often, 42% saw a close relative once a week or more often and just over half (53%) spent almost all their leisure time with others.

Most (87%) respondents said that among their friends and family there was someone they could confide in or talk freely to about their problems and nearly all (96%) had someone they could turn to in times of trouble, a similar result to that seen in 1996 (97%).

General well-being

As explained in the methods, the survey included a question consisting of 14 statements describing feelings of positive and negative well-being. Respondents were asked to indicate (using a four point scale) how often during the past year they had experienced each of the feelings described and the responses were used to calculate a score for each respondent. Analysis of the results showed that more than half (57%) of respondents mostly had feelings of positive well-being (a score of 43-56), and only 1% experienced mainly negative feelings (a score of 14 or less). The remaining 42% scored between 15 and 42 (6% 15-28 and 36% 29-42). In 1996, analysis of the General Well-being Scale showed that 86% had feelings of positive well-being, whilst 7% felt moderate distress and 4% were under severe distress.8

The results showed that 12% (62) of dentists had thought about committing suicide and of those 18 had considered this in the past year. Seven respondents had attempted suicide but none had done so in the past year. These results are comparable to those seen in 1996 when 12% (91) of dental professionals (GDPs and dental support staff) had thought about committing suicide, 31 in the previous year. In 1996, 13 respondents had attempted suicide, one within the past year.

Female health

Respondents to the survey included 176 women. Most (61%) of these had had a cervical smear in the two years preceding the survey, although this was a smaller proportion than the 70% of female dental professionals (GDPs and dental support staff) in 1996. The proportion of women who had had a breast examination in the past two years had also decreased, from 44% in 1996 to 28% in 2005.

Only 22% of female respondents had ever had a mammogram, although 80% of females aged 50 or over had done so. Less than a quarter (22%) of female respondents took oral contraceptives, compared with 35% of those aged under 35 years. Only 5% took female hormones.

Nearly two-thirds (64%) of female respondents had children and the majority (86%) of these had breast fed their last child. Less than half (43%) had been pregnant in the last five years and 82% of pregnancies occurring in the last five years had been planned.

Sexual health

The results for the 2005 survey indicated that 96% of respondents had had a sexual partner in the preceding year and 5% had first had sexual intercourse when they were below the age of 16. In 1996, 91% of dental professional had a sexual partner and 9% had had sex before the age of 16. With regard to risk behaviour for HIV, 1% of respondents had placed themselves at high risk through sexual behaviour or drug use. In 1996 eight dental personnel had placed themselves at high risk (also approximately 1% of respondents).

Of those dentists who had had a sexual partner in the past year, only 9% had had more than one partner. More than half (54%) said they always used some form of birth control, but a third (33%) said they never used any form of birth control. The most popular forms of birth control were condoms (29%), pills (19%) and vasectomy or tubal ligation (21%). Of those who never used birth control, 51% were past child-bearing age, 15% wanted to become parents and 10% were unable to have children.

Occupational stress

Table 8 shows how frequently dental practitioners experience certain potentially harmful situations at work. As can be seen from the table, 38% of dentists often carry out work requiring repeated hand and arm movements and 40% always do this type of work (compared with 29% of dental professionals in 1996). More than a quarter (26%) of respondents always work with their back in an awkward position and 42% often have this problem. These results are similar to 1996, when 24% always had their back in an awkward position and 41% often did so.

Respondents were asked what contributed most to feelings of stress at work. As can be seen from Table 9, the most common factors were patient demands (75%), practice management/staff issues (56%), fear of complaints/litigation (54%) and non-clinical paperwork (54%).

Physical activity

More than half (53%) of dentists are relatively inactive during the day (ie they are usually sitting down and do not walk about very much). A further 40% stand or walk about quite a lot during the day but do not have to carry or lift things very often. Only 17% of respondents took some form of physical exercise (including playing sport, walking, gardening, etc) every day but 40% did so three to four times per week. Half (49%) of respondents exercise for 30-59 minutes per occasion and a quarter (26%) spend one to two hours at a time doing physical exercise. Forty-three percent said that most or all of their friends took part in regular physical exercise. Half (49%) had had their blood pressure checked in the six months preceding the survey and two-thirds (66%) had had this done in the past year. Half (49%) of respondents felt that their level of physical activity was very likely or somewhat likely to cause them health problems. In 1996 only 40% of dental personnel thought their level of activity was likely or somewhat likely to cause them health problems.

Only 35% of respondents to the 2005 survey ate five or more portions of fruit and vegetables per day and nearly two-thirds (65%) thought they could improve their health by changing their eating habits. In 1996 69% of dental professionals felt that they could improve their health by changing their diet. The average (mean) BMI of all respondents to the 2005 survey was 25.6, compared with an average of 26.2 for male respondents and 24.5 for female respondents. Figure 5 shows the BMI ranges for respondents to the survey.

As can be seen from the chart, nearly half (47%) of respondents fall within the healthy BMI range of 18.5-24.9, but 39% overall are classed as overweight (BMI of 25.0-29.9) and 13% are obese (BMI of 30.0 or more). The results for men and women differ, with 65% of women falling within the healthy BMI range, compared with 39% of men. Half (49%) of respondents were happy with their weight (49% of men and 50% of women).

Discussion

When interpreting the results of this research, the limitations of the study need to be taken into consideration. The questionnaire was not sent to all 22,500 BDA members, and not all of those who received a survey responded. There may therefore be an element of non-response bias, although with a response rate of 55% from a sample size of 1,000 this is probably minimal. The results are compared to those obtained in the very similar study carried out in 1996. Some results are not directly comparable but were the best data available for comparison.

It is interesting to observe that in spite of the dramatic changes to dentistry which have taken place, there is not a great deal of difference between the results of this study and the results of the research carried out in 1996. It is reassuring that the proportion of respondents who were happy and interested in life has remained similar (53%, compared with 50% in 1996). However, it is worrying that the proportion of respondents who consider their lives to be very or fairly stressful remains high (86%, compared with 85% in 1996).

There are a few areas where the results do differ and it is perhaps worth looking at these in more depth. Firstly, it is worthy of note that two-thirds (67%) of respondents to the survey considered themselves to be in very good or excellent health, an increase on the 59% in 1996.

There has been a decrease in the proportion of women actively participating in preventive interventions for cancer. Only 28% of women had had a breast examination in the previous two years, compared with 44% in 1996. Similarly, 61% of female respondents had had a cervical smear in the two years preceding the survey compared to; 70% of female dental professionals in 1996. This is worrying when we consider that each year more than 44,000 people in the UK are diagnosed with breast cancer (16% of all cancers) and breast cancer causes more than 12,500 deaths each year in the UK.16 Cervical cancer represents a smaller percentage of cancers overall, but more than 2,800 women are diagnosed with this each year in the UK and cervical cancer causes almost 1,100 deaths each year in the UK.

It is reassuring that the results of this study suggest that the number of people having underage sex has decreased over the last decade. Only 5% of respondents to this study had had sexual intercourse when they were below the age of 16, compared with 9% of those surveyed in 1996.

One aspect of occupational health which has not improved a great deal during the last ten years is the fact that the majority of dentists frequently work with their backs in an awkward position. More than a quarter (26%) of respondents to the survey always work with their backs in an awkward position and 42% often have this problem. In 1996, 24% always had their backs in an awkward position and 41% often did so. This could lead to back problems in later life and is therefore a cause for concern which needs to be addressed. This is further supported by the results of a recent study of stress and health in GDPs which found that 63% respondents reported backache or pains in the back.7 Posture should be included on dental school curricula and dental students should be taught how to sit in a way that will minimise their risks of back trouble.

The factors which contributed most to feelings of stress at work were patient demands (75%), practice management/staff issues (56%), fear of complaints/litigation (54%) and non-clinical paperwork (54%). In 2002 a study of levels of self reported stress amongst GDPs in Somerset and Dorset9 included a similar question, which asked respondents to rank 12 factors according to the amount of stress that each placed on them. The factors listed were the same as those in the BDA survey but the questions were worded differently so the results are not directly comparable. The factors which were ranked highest by the GDPs in the 2002 survey were patient demands, practice management/staff issues and being available 24 hours a day.

The results of the Short Michigan alcohol screening test15 indicated that dentists seem more likely to have alcoholic tendencies than they were ten years ago. In 1996 the test showed that 5% of GDPs had a drink problem and 5% had alcoholic tendencies. The same test on the results from this study revealed that 6% of respondents had a drink problem and 9% had alcoholic tendencies.

In the early 1990s, the Lord President's Report on Alcohol Misuse and the Department of Health's paper 'The Health of the Nation - a strategy for health in England' defined sensible drinking as less than 21 units per week for men and less than 14 units per week for women.17,18 In their report 'Sensible Drinking' (1995),19 the Department of Health changed the guidelines for sensible drinking from a weekly to a daily measure of consumption, reflecting concern that 'weekly consumption can have little relation to single drinking episodes and may indeed mask short term episodes which ... often correlate strongly with both medical and social harm'. The report concluded that regular consumption of three to four units per day for men and two to three units per day for women would not accrue significant health risk. In the light of these guidelines, it is worthy of concern that 32% of women had at some point in their lives regularly drunk more than 14 units per week, and even more worrying that 58% of men had at some time regularly drunk more than 21 units per week. It could be assumed that the majority of excessive drinking occurs when dentists are at dental school, but results of a study of patterns of drinking in a UK dental school conducted in 2002 suggest that this is not necessarily the case. This research showed that the proportion of individuals drinking above the recommended weekly limits (14 units or more for women and 21 units or more for men) declined from 47% as second year students to 25% as final year students, but then increased back to 41% as qualified dentists.20

There is no internationally agreed definition of binge drinking, but in the UK, drinking surveys normally define binge drinkers as men consuming at least eight, and women at least six standard units of alcohol in a single day.21,22 These figures are derived from the Office for National Statistics (ONS) report of the 1998 General Household Survey, which defined drinking 'heavily' as having consumed more than eight units (men) or six units (women) of alcohol on a single occasion.23 Based on this definition, the results of this study indicate that 35% women and 38% of men had 'binge-drinking' sessions at least once a month. It is encouraging therefore that 18% of respondents planned to drink less alcohol to improve their lifestyles over the next 12 months.

Current classification of BMI values for adults, as used in the NICE clinical guideline on obesity,24 is shown in Table 10. These values originate from similar values used in the 1998 Health Survey for England25 and the 2001 National Audit Office report 'Tackling Obesity in England'.26

The NICE clinical guideline on obesity24 estimates that currently around 20% of the UK adult population is obese, whilst about 50% of UK adults are overweight. The results of this study revealed that 13% of respondents were obese and 39% were classed as overweight. These proportions are lower than the national averages quoted in the NICE guidance, but are still worryingly high and are higher than those reported in the recent (2004) study of stress and health in UK dentists, which found that one third of respondents were overweight or obese.7 It is therefore reassuring to note that only half (49%) of respondents were happy with their weight and 42% of respondents planned to lose weight in the year following the survey.

Diet and physical activity are important factors in weight management and overall health. Nearly two-thirds (65%) of respondents thought they could improve their health by improving their eating habits but unfortunately only 32% planned to do this in the year following the survey. In recent years the UK government has been trying to raise awareness of the important of a healthy diet. The '5 a day' campaign27 aims to publicise the benefits of eating five or more portions of fruit and vegetables each day: increasing consumption of fruit and vegetables can significantly reduce the risk of many chronic diseases and it has been shown that eating at least five portions of a variety of fruit and vegetables a day could reduce the risk of death from diseases such as heart disease, stroke, and cancer.28 In spite of such campaigns, only 35% of respondents ate five or more portions of fruit and vegetables each day. On a more positive note, more than half (57%) of respondents took part in some form of physical exercise at least three or four times a week and 58% planned to increase this during the following year.

This study focussed on UK dentists, but it is worth noting that similar studies have shown that dentistry is also considered to be a stressful occupation in other countries.29,30

Conclusions

Overall this study has provided further evidence that dentistry can be a stressful occupation. However, whilst many of the participants reported that they had very or fairly stressful lives, it must be remembered that stress can be a positive factor which stimulates and enhances well-being and that stress creates negative impacts only if it is overwhelming. The dentists in this study are as well and happy as other professional groups. However, there do seem to be slight increases in alcohol use: trends such as these, although minimal and possibly attributable to sampling error, should be monitored and acted upon if continued.

Preparation for life as a general dental practitioner occurs at university. Stress management and personal and professional awareness training need to be included in the undergraduate curriculum, so that threats to physical and mental well-being caused or associated with the practice of dentistry may be avoided or addressed.

References

Freeman F, Main J R R, Burke F J T . Occupational stress and dentistry: theory and practice. Part I. Recognition. Br Dent J 1995; 178: 214–217.

Freeman R, Main J R R, Burke F J T . Occupational stress and dentistry: theory and practice. Part II. Assessment and control. Br Dent J 1995; 178: 218–222.

George J M, Milone C L, Block M J, Hollister W G . Stress management for the dental team, 1st ed. pp 43–97. Phildelphia: Lea and Febiger, 1986.

Christen A . Stress and distress in dental practice. In Goldman H S, Hartman K S, Messite J (eds). Occupational hazards in dentistry, 1st ed. pp 151–170. Yearbook Medical Publishers, 1984.

Cooper C, Watts J, Kelly M . Job satisfaction, men tal health and job stressors among general dental practitioners in the UK. Br Dent J 1987; 162: 77–81.

Cooper C, Humphris G M . New stressors for GDPs in the past ten years: a qualitative study. Br Dent J 1998; 185: 404–406.

Myers H L, Myers L B . 'It's difficult being a dentist': stress and health in the general dental practitioner. Br Dent J 2004; 197: 89–93.

Kay E J, Scarrott D M . A survey of dental professionals' health and well being. Br Dent J 1997; 183: 340–345.

Hughes J, Coe N . Study of stress in GDPs in Somerset and Dorset 2002 (unpublished).

Occupational Health Services for General Dental Practitioners and their Staff 2003/04, R Bedi (Chief Dental Officer – England), NHS Gateway Communication Reference No. 2595. www.dh.gov.uk/assetRoot/04/07/07/16/04070716.pdf Accessed on 7 August 2007.

Lowe C . Occupational Health – contact your PCT now. bdanews 2004; 17(12): 2

Cooper C, Payne R . Causes, coping and consequences of stress at work. Chichester: Wiley, 1994.

Lowe C . General health and well-being survey. bdanews 2005; 18(5): 3.

Edwards P, Roberts I, Clarke M et al. Methods to increase response rates to postal questionnaires (review). The Cochrane Collaboration 2007; Issue 3.

Selzer M L, Vinokur A, van Rooijen L. A self administered Short Michigan Alcoholism Screening Test (SMAST). J Stud Alcohol 1975; 36: 117–126.

Cancer Research UK . UK Breast Cancer Statistics, July 2007. http://info.cancerresearchuk.org/cancerstats/types/breast/ Accessed on 7 August 2007.

The Lord President. Report on Action Against Alcohol Misuse. London: Her Majesty's Stationery Office, 1991.

Department of Health. The health of the nation – a strategy for health in England. London: Her Majesty's Stationery Office, 1992.

Department of Health. Sensible drinking: the report of an inter-departmental working group. London, 1995. www.dh.gov.uk/assetRoot/04/08/47/02/04084702.pdf Accessed on 7 August 2007.

Newbury-Birch D, Lowry R J, Kamali F . The changing patterns of drinking, illicit drug use, stress, anxiety and depression in dental students in a UK dental school: a longitudinal study. Br Dent J 2002; 192: 646–649.

Institute of Alcohol Studies. Binge drinking: nature, prevalence and causes. St Ives, Institute of Alcohol Studies, updated June 2007. www.ias.org.uk/resources/factsheets/binge_drinking.pdf Accessed 7 August 2007.

Alcohol Concern. Binge drinking. Factsheet. London: Alcohol Concern, 2002.

Office for National Statistics. First release: Living in Britain 1998, General Household Survey. London, 1999.

National Institute for Clinical Excellence. Clinical Guideline. Obesity: the prevention, identification, assessment and management of overweight and obesity in adults and children, December 2006. http://guidance.nice.org.uk/CG43 Accessed on 7 August 2007.

Joint Health Surveys Unit, on behalf of the Department of Health. Health Survey for England: Cardiovascular Disease. London: The Stationery Office, 1998, 1999.

National Audit Office. Tackling Obesity in England Progress Report, London: Her Majesty's Stationery Office, 2001.

NHS 5 a day campaign. www.5aday.nhs.uk Accessed on 7 August 2007.

Department of Health. The NHS Plan. London: The Stationery Office, 2000.

Leggat P A, Chowanadisai S, Kedjarune U, Kukiattrakoon B, Yapong B . Health of dentists in Southern Thailand. Int Dent J 2001; 51: 348–352.

Möller A T, Spangenberg J J . Stress and coping amongst South African dentists in private practice. J Dent Assoc S Afr 1996; 51: 347–357.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Refereed paper

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Kay, E., Lowe, J. A survey of stress levels, self-perceived health and health-related behaviours of UK dental practitioners in 2005. Br Dent J 204, E19 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.2008.490

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.2008.490

This article is cited by

-

The health of the dental professional part 1: Ill health

BDJ In Practice (2024)

-

A survey of mental wellbeing and stress among dental therapists and hygienists in South West England

BDJ Team (2023)

-

Dentistry and mental health: The need for psychological interventions

BDJ In Practice (2023)

-

Levels of perceived stress according to professional standings among dental surgeons of Karachi: a descriptive study

BMC Oral Health (2022)

-

A survey of mental wellbeing and stress among dental therapists and hygienists in South West England

British Dental Journal (2022)