Key Points

-

Dramatically changes the surgical intervention for migrated dental implants and maxillary sinus foreign bodies.

-

Patients have substantial benefit and decreased morbidity.

-

Outlines interaction between dentists, maxillofacial surgeons and ENT surgeons.

Abstract

We report a case of migration of a dental implant into the maxillary sinus and discuss the benefits of endoscopic transnasal removal of such implants. As the sole approach, this technique has rarely been described.1,4,6,10 The most commonly used technique for retrieval of dental implants is the Caldwell-Luc procedure. This, however, has certain morbidity associated with it and may compromise subsequent implant insertion.

Similar content being viewed by others

Case report

A 46-year-old female presented to a general dental practice complaining of an unaesthetic smile associated with a missing upper premolar tooth. In addition she was concerned about an edentulous space created by a previously extracted upper molar. An intra-oral examination revealed a normal class 1 occlusion, good oral hygiene and a caries free dentition. Several teeth were missing due to previous extractions. This subsequently created an unaesthetic gap between the upper left first premolar and the upper left first molar.

Several treatment options were discussed with the patient and it was finally decided that an implant supported fixed restoration in the region of the second left upper premolar as well as the right upper second molar would provide the best long-term benefit for the missing teeth.

Subsequently, surface-roughened, titanium dental implants were placed under local anaesthesia in the affected areas. Because the patient desired an aesthetic result as soon as possible, as well as the fact that the implant placed in the premolar region showed good primary stability, it was decided to place a temporary restoration on the implant immediately following implant placement.

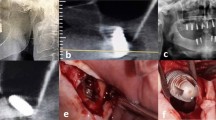

The patient returned seven days post implant placement for a routine follow up and showed no adverse effects from the treatment provided. Three weeks subsequently, the patient returned complaining that 'the tooth had fallen out' and of 'mild pain on the left side of the face'. Clinical examination revealed no complications associated with the implant placed in the molar region. However, the implant which received the temporary restoration was not clinically visible. An orthopantomogram (Fig. 1) revealed that the implant was dislodged into the posterior region of the left maxillary sinus. Upon prompting, the patient admitted that the temporary crown was lost two weeks previously and since then she had been eating on the exposed part of the implant.

The displacement of the implant into the sinus necessitated surgical removal and she was subsequently referred to a maxillofacial surgeon for further management.

The standard Caldwell-Luc procedure would have made subsequent implant insertion difficult or impossible and the otolaryngologist was consulted with regard to possibly removing it through an endoscopic transnasal approach. An endoscopic uncinectomy and middle meatal antrostomy was performed and the implant easily identified in the posterior-medial aspect of the maxillary sinus. A 30-degree endoscope was used to visualise the implant (Fig. 2) and a curved forceps used to atraumatically remove it from the maxillary sinus.

Discussion

A PubMed search reveals that only seven cases of endoscopic removal of dental implants and dental foreign bodies have been described in the maxillofacial literature.1,2,3,4,5,6,7 Similarly, the ENT literature has sparse data and mentions a single study referring to endoscopic removal of dental implants.8 The use of the trans-nasal, trans-antral approach as the sole intervention has only been mentioned on four occasions.1,4,6,10 More commonly, the trans-oral endoscopic approach was used.2,3,7,8,11 A combined approach, trans-nasal and trans-oral was also described.9 Various other studies refer to the use of endoscopy for removal of other foreign bodies including amalgam and teeth roots amongst others.9,10,11 A single article compares the complications of this alternative to the classic Caldwell-Luc procedure.12 The sublabial (labial vestibular) incision results in significant postoperative discomfort. The subperiosteal dissection can cause injury to branches of the infra-orbital nerve with subsequent anaesthesia of the gingivo-buccal mucosa and teeth and the Caldwell-Luc approach has the attendant risk of causing an oro-antral fistula if the periosteum is not closed adequately. Endoscopic removal is minimally invasive with quicker operative time and postoperative recovery. Patients can be discharged on the same day. With the transnasal endoscopic approach, bony alveolar integrity is maintained and further dental implant surgery can be done without the need for a sinus lift procedure. Dental implants are costly and the retrieved migrated implants need to be tested to ascertain the reasons for non-integration. Uncinectomy is unlikely to be associated with any adverse effects if performed by a trained endoscopic sinus surgeon. It takes no more than a few minutes to expose the normal maxillary sinus ostium that can then be widened. A large middle meatal antrostomy (MMA) is necessary in order to manoeuvre angled instruments for foreign body removal. Few randomised trials exist to compare the outcomes of small versus large middle meatal antrostomies in the treatment of chronic sinusitis and symptomatic relief.13,14 There is no reason to believe that a large antrostomy would place a patient at risk for developing sinusitis.

Endoscopic sinus surgery is not without its risks and vital structures such as the orbit and lacrimal duct system are potentially at risk during an uncinectomy/middle meatal antrostomy. During the uncinectomy, the orbit can be injured if instruments breach the lamina papyracea that lies just above the level of the normal maxillary ostium and just a few millimetres lateral to the uncinate. The nasolacrimal duct can be injured during the MMA. This usually happens if the MMA is enlarged too far anteriorly. It is therefore much safer to always enlarge the MMA posteriorly, keeping in mind that the sphenopalatine artery can be traumatised where the posterior aspect of the middle turbinate inserts on the lateral wall of the nose. This will lead to significant bleeding.

Comment

Endoscopic transnasal removal of dental implants and other foreign bodies within the maxillary sinus is a safe and minimally invasive procedure compared to the classic Caldwell-Luc procedure. Since the advent of endoscopic sinus surgery, interdisciplinary cooperation between specialties has increased, such as this example of otolaryngology and maxillofacial interaction. We feel that an otolaryngologist should review all maxillary antrum lesions in order to assess the role of minimal access endoscopic removal. The Caldwell Luc operation should be largely obsolete in these cases.

References

Varol A, Turker N, Goker K, Basa S . Endoscopic retrieval of dental implants from the maxillary sinus. Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants 2006; 21: 801–804.

El Charkawi H G, El Askary A S, Ragab A . Endoscopic removal of an implant from the maxillary sinus: a case report. Implant Dent 2005; 14: 30–35.

Nakamura N, Mitsuyasu T, Ohishi M . Endoscopic removal of a dental implant displaced into the maxillary sinus: technical note. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2004; 33: 195–197.

Kitamura A . Removal of a migrated dental implant from a maxillary sinus by transnasal endoscopy. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2007; 45: 410–411.

Felisati G, Lozza P, Chiapasco M, Borloni R . Endoscopic removal of an unusual foreign body in the sphenoid sinus: an oral implant. Clin Oral Implants Res 2007; 18: 776–780.

Kim J W, Lee C H, Kwon T K, Kim D K . Endoscopic removal of a dental implant through a middle meatal antrostomy. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2007; 45: 408–409.

Friedlich J, Rittenberg B N . Endoscopically assisted Caldwell-Luc procedure for removal of a foreign body from the maxillary sinus. J Can Dent Assoc 2005; 71: 200–201.

Pagella F, Emanuelli E, Castelnuovo P . Endoscopic extraction of a metal foreign body from the maxillary sinus. Laryngoscope 1999; 109: 339–342.

Lopatin A S, Sysolvatin S P, Sysolvatin P G, Melnikov M N . Chronic maxillary sinusitis of dental origin: is external surgical approach mandatory? Laryngoscope 2002; 112: 1056–1059.

Connolly A, White P . How I do it: transantral endoscopic removal of maxillary sinus foreign body. J Otolaryngol 1995; 24: 73–74.

Sugiura N, Ochi K, Komatsuzaki Y . Endoscopic extraction of a foreign body from the maxillary sinus. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2004; 130: 279–280.

Ikeda K, Hirano K, Oshima T, Shimomura A et al. Comparison of complications between endoscopic sinus surgery and Caldwell-Luc operation. Tohoku J Exp Med 1996; 180: 27–31.

Albu S, Tomescu E . Small and large meatal antrostomies in the treatment of chronic maxillary sinusitis. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2004; 131: 542–547.

Salam M A, Cable H R . Middle meatal antrostomy: long-term patency and results in chronic maxillary sinusitis. A prospective study. Clin Otolaryngol Allied Sci 1993; 18: 135–138.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Refereed paper

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Lubbe, D., Aniruth, S., Peck, T. et al. Endoscopic transnasal removal of migrated dental implants. Br Dent J 204, 435–436 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.2008.293

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.2008.293

This article is cited by

-

The Transoral Endoscope-Assisted Approach for Removal of a Dental Implant Displaced into the Maxillary Sinus: A Case Report and Review of the Literature

Journal of Maxillofacial and Oral Surgery (2022)