Abstract

Myelopathy is one of the neuropsychiatric lupus syndromes. In this article, an original series of related lupus myelitis is reported and analyzed. We employed a retrospective chart review and identified all patients who were admitted to a general hospital in Buenos Aires, Argentina, with SLE and myelitis during the period 2007–2014. Five patients were observed, all women. The mean age was 25.4 years (19–39). In three of five cases, myelitis was one of the initial SLE manifestations. The SLE Disease Activity Index was variable (3/5 with high activity). Time to nadir ranged from 6 to 72 h. All had severe impairment, with motor deficit, sensory level and urinary retention. Magnetic resonance imaging was abnormal in all cases, 3/5 presented a longitudinally extensive myelitis. Serum analysis revealed positive antinuclear antibodies at a high titer in all patients, 4/5 had low complement levels and 3/5 had anti-phospholipids positive. The treatment (methylprednisolone and, in some cases, cyclophosphamide, anticoagulation and/or plasmapheresis) produced partial improvement or no benefits. One patient died due to sepsis. The others showed significant disability at 6 months (European Database for Multiple Sclerosis grading scale=6–8). In view of these results, myelitis associated with lupus shows heterogeneity of the clinical, radiological and serological features. In our experience, the cases were severe and with poor response to treatment. Further studies are required to understand this disease and establish a more efficient treatment.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) is a complex multisystem chronic autoinflammatory disease characterized by hyperactive autoreactive B and T cells, and inflammation induced by immune complexes that has systemic clinical manifestations and follows a relapsing and remitting course.1 Neuropsychiatric involvement in SLE (NPSLE) includes a broad spectrum of neurologic and psychiatric manifestation. In 1999, the Research Committee of the American College of Rheumatology (ACR) defined 19 neuropsychiatric syndromes: one of them is myelopathy.2 Acute transverse myelitis (ATM) is acute inflammation of gray and white matter in one or more adjacent spinal cord segments. Symptoms and sign include bilateral motor, sensory, and sphincter deficits below the level of the lesion.3 Prevalence of ATM in the general population is estimated at 1–4 new cases per million per year, while in SLE it is seen in 1–2% of patients, 1000 times greater than the general population.4 Although SLE-related myelitis is traditionally regarded as a single diagnostic entity, case reports and cohort studies show clinical and probably physiopathogenic heterogeneity.4–14 The aim is to communicate and analyze an original series of SLE-related myelitis observed consecutively in a general hospital in Buenos Aires, Argentina.

Subjects and methods

We employed a retrospective chart review of inpatient medical records at Carlos G. Durand Hospital, and identified all patients who were admitted to the hospital with SLE and myelitis during the period 2007–2014. All meet the revised criteria of ACR of SLE1 and NPSLE,2 and comply with the Transverse Myelitis Consortium Working Group (TMCWG) definition of myelitis.3 We compiled a database that included demographics, clinical variables, laboratory results, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), autoantibodies profiles, treatment and clinical outcomes. The Systemic Lupus Erythematosus Disease Activity Index (SLEDAI)15 was measure retrospectively at myelitis diagnosis. Also, we evaluated the neurological impairment at nadir and 6 months later with the American Spinal Injury Association impairment scale (AIS) and the European Database for Multiple Sclerosis grading scale (EGS). The AIS is determined according to the motor and sensory findings on neurological examination (A=injury is complete, B=motor complete and sensory incomplete, C and D=motor incomplete with different impairment of motor function and E=normal).16 The EGS is a simplified version of the Kutzke Expanded Disability Status Scale (EDSS). This scale mainly values the ability to walk (1–3: unlimited walk distance, 4–5: walk without aid > or <500 m, 6–6.5: walk with support, 7: home restricted; 8: chair restricted; 9: bedridden and totally helpless and 10: death).14–17 All patients were assessed with analysis of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) by lumbar puncture. Lupus anticoagulant (LA), anticardiolipin (aCL) antibody of IgG and IgM isotype, anti-β2 glycoprotein-I antibody (a-β2GP1) of IgG and IgM isotype were measured according to recommended procedures.18 In serum that were measured complement levels (C3 and C4, using nephelometry) and the presence of autoantibodies: antinuclear antibodies (ANA, indirect immunofluorescence (IFI) using Hep-2 cell culture with a cut off:1/80) and anti-double-stranded DNA (anti-dsDNA, using enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay, cut off:30) at least. Spinal and brain MRI was performed on a 1.5 tesla machine. Spinal cord lesions which extend through three or more vertebral segments on sagittal spinal MRI is regarded longuitudinally extensive transverse myelitis (LETM).

Results

Five patients with myelitis and SLE were observed. During the same period, 233 patients with SLE were recorded by the Department of Immunology. In view of these data, the prevalence of myelitis in this population can be estimated at 2.1%. In the same way, 46 acute myelitis were observed by the Department of Neurology, 10.8% of them were associated with lupus.

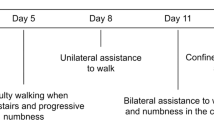

Table 1 shows the demographic and clinical characteristics: all were women, the mean age was 25.4 years (range:19–39). In three of five cases, myelitis was one of the initial SLE manifestations. Fever was the most frequent associated manifestation (4/5). One patient presented concomitant glomerulonephritis and another patient had acute arthritis. The SLEDAI showed high disease activity (>4) in three patients. The clinical picture was acute and severe; all with motor deficit, sensory level and urinary retention. The AIS and EGS was high.

MRI findings, CSF and serological features are shown in Table 2. Spinal MRI was abnormal in all cases, three presented a longitudinally extensive myelitis (Figures 1 and 2). Brain MRI showed no significant lesions. Serum analysis revealed positive ANA at a high titer in all patients, four had low complement levels and three had anti-phospholipids positive. Only two patients were tested for the presence of aquaporin-4 antibody (AQP4-ab) by IFI with negative results. CSF analysis was abnormal in all cases with variable results.

All patients received high-dose intravenous (i.v.) methylprednisolone, 1 g daily for 5 days. Patients 1, 4 and 5 were also treated with cyclophosphamide. In cases that showed positive antiphospholipid antibodies (1, 2 and 5) anticoagulation was initiated with low-molecular-weight heparin. Owing to the poor response, patients 3 and 4 received plasmapheresis or i.v. immunoglobulin (Table 3). The treatment produced only partial improvement or no benefits. One patient died due to sepsis (probably secondary to mesenteric ischemia). The others showed significant disability. The neurological impairment at six months was high: AIS A=1, C=1 and D=2, and EGS=6 (walks with permanent unilateral support, walking distance <100 m without rest) to 8 (chair restricted, unable to take a step, effective use of arms).

Discussion

NPSLE is one of the major causes of morbidity and mortality in patients with SLE. Myelitis is one of these syndromes and may be the initial SLE manifestations (60% in our series), though myelitis also occur many year after SLE diagnosis.4–14 We estimated the prevalence of myelitis in SLE at 2.1%, in line with previous reports.4 The clinical presentation may be hyperacute, acute or subacute with motor impairment, sensory level and sphincter disturbances. There are often systemic symptoms such as fever and other signs of disease activity with or without involvement of other organs.4–14 Nearly two-thirds of cases occurred in association with active lupus, and one-third occurred in low disease activity.13 In other series12–14 the prevalence of relapse is high (50–60%) but in our series no patient had a relapse probably for the short follow-up period.

In patients with suspected myelopathy a contrast-enhanced spinal cord MRI and lumbar puncture should be performed. MRI is useful to exclude cord compression and detect T2-weighted hyperintense lesions. These lesions are seen in most patients and frequently (60–75%) are LETM.9,12–14 such as was observed in our cases. CSF analysis is abnormal in most patients and show great variability:4–14 there may be only a slight increase of proteins and cells to polymorphonuclear pleocytosis with hypoglycorrhachia in hyperacute cases (for example, in case 4). Serum analysis revealed positive ANA at a high titer in all patients. Other autoantibodies, particularly anti-DNA, are also positive. Often, complement levels are low.

In the patients with LETM and SLE the AQP4-ab was positive in a variable percentage (12–57%).12,19,20 Whereas the AQP4-ab detection is a specific marker that distinguishes neuromyelitis optica (NMO) from other etiologies, in these patients, coexisting pathologies is postulated.19 In two of our patients have been tested for the presence of these antibodies by IFI with negative results. The sensitivity depends on the method of detection: assay based on cells transfected with AQP4-M23 isoform were the most sensitive but is not widely available.21

The presence of antiphospholipid antibodies is found in a high percentage (60% in our cases, 50–70% in the literature).10–14 We started anticoagulant therapy in these cases, but its usefulness is controversial and is not routinely indicated.10,11,22 The antiphospholipid antibodies may have a pathogenic role related to the interaction with certain antigens of the spinal cord and not necessarily secondary to thrombosis, or they could be an epiphenomenon.10,11,14

Birnbaum et al.12 propose the existence of different subtypes of myelitis associated with lupus: patients with ‘gray matter myelitis’ and patients with ‘white matter myelitis’. The first one has a more acute and severe clinical picture, flaccidity, hyporeflexia, with more symptoms and signs of systemic and local inflammation, extensive central lesions and worse prognosis. In this cases, recognition of fever and urinary retention as prodromes of irreversible paraplegia may allow early diagnosis and treatment. The patients with ‘white matter myelitis’ have spasticity and hyperreflexia and greater association with antiphospholipid antibodies and AQP4-ab. This group has higher recurrence rate but better prognosis. In our series, cases 1, 2 and 5 can be classified within subtype of ‘white matter myelitis’ associated to antiphospholipid antibodies and case 3 and, in particular, case 4, can fall into the subtype of ‘gray matter myelitis’.

There are no large prospective studies on the treatment of lupus myelitis.22–24 The European League Against Rheumatism in 2010 issued recommendations for NPSLE management.22 If there is high suspicion of SLE-myelitis, the combination of methylprednisolone i.v. and cyclophosphamide i.v. should be initiated promptly. A maintenance therapy with a less intensive immunosuppression may be considered to prevent recurrence. Retrospectives studies support these recommendations.14,23,24 Plasma exchange therapy, i.v. immunoglobulin and rituximab25 have been used in refractory cases and anticoagulation therapy in antiphospholipid-positive with variable results.10,11,22 In our experience the treatment produced only partial improvement.

The prognosis is variable. In our cases, despite treatment, none had complete recovery, 40% had partial improvement, 40% showed no improvement and one case died in the hospital, probably due to a complication related to SLE. In previous reports4–14 the outcomes are somewhat better, and depend on the initial clinical picture. In the most recent series published,14 ~60% have a complete or nearly complete recovery at year.

Although this study is retrospective and with limited number of patients, it is the largest case series of patients with SLE and myelitis reported in Argentina and provides the data to international casuistry. The five cases described show the heterogeneity of the clinical, radiological and serological features. Rapid diagnosis and early treatment with methylprednisolone and cyclophosphamide is recommended to improve the prognosis, but, in our experience, the cases were severe and with poor response to treatment. In accordance with expert opinions, prospective and controlled studies and perhaps the creation of registry for SLE patient with myelitis are needed to help understand this disease and establish more efficient treatment strategy.

References

Hochberg MC . Updating the American College of Rheumatology revised criteria for the classification of systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum 1997; 40: 1725.

ACR ad hoc Committee on Neuropsychiatric Lupus Nomenclature The American College of Rheumatology nomenclature and case definitions for neuropsychiatric lupus syndromes. Arthritis Rheum 1999; 42: 599–608.

Transverse Myelitis Consortium Working Group. Proposed diagnostic criteria and nosology of acute transverse myelitis. Neurology 2002; 59: 499–505.

Kovacs B, Lafferty TL, Brent LH, DeHoratius RJ . Tranverse myelopathy in systemic lupus erythematosus: an analysis of 14 cases and review of the literature. Ann Rheum Dis 2000; 59: 120–124.

Schulz SW, Shenin M, Mehta A, Kebede A, Fluerant M, Derk CT . Initial presentation of acute transverse miyelitis in systemic lupus erythematosus: demographics, diagnosis, management and comparison to idiopathic cases. Rheumatol Int 2012; 32: 2623–2627.

Espinosa G, Mendizábal A, Mínguez S, Ramo-Tello C, Capellades J, Olivé A et al. Transverse Myelitis affecting more than 4 spinal segments associated with systemic lupus erythematosus: clinical, inmunological, and radiological caracteristics of 22 patiens. Semin Arthritis Rheum 2010; 39: 246–256.

Lu X, Gu Y, Wang Y, Chen S, Ye S . Prognostic factors of lupus myelopathy. Lupus 2008; 17: 323–328.

Gómez-Argüelles JM, Martín-Doimeadios P, Sebastián-De la Cruz F, Romero-Ganuza FJ, Rodríguez-Gómez J, Florensa J et al. Mielitis transversa aguda en siete pacientes con lupus eritematoso sistémico. Rev Neurol 2008; 47: 169–174.

Téllez-Zenteno JF, Remes-Troche JM, Negrete-Pulido RO, Dávila-Maldonado L . Longitudinal myelitis associated with systemic lupus erythematosus: clinical features and magnetic resonance imaging of six cases. Lupus 2001; 10: 851–856.

D'Cruz DP, Mellor-Pita S, Joven B, Sanna G, Allanson J, Taylor J et al. Transverse myelitis as the first manifestation of systemic lupus erythematosus or lupus-like disease: good functional outcome and relevance of antiphospholipid antibodies. J Rheumatol 2004; 31: 280–285.

Katsiari CG, Giavri I, Mitsikostas DD, Yiannopoulou KG, Sfikakis PP . Acute transverse myelitis and antiphospholipid antibodies in lupus. No evidence for anticoagulation. Eur J Neurol 2011; 18: 556–556.

Birnbaum J, Petri M, Thompson R, Izbudak I, Kerr D . Distinct subtypes of myelitis in systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum 2009; 60: 3378–3387.

Li XY, Xiao P, Xiao HB, Zhang LJ, Pai P, Chu P et al. Myelitis in systemic lupus erythematosus frequently manifests as longitudinal and sometimes occurs at low disease activity. Lupus 2014; 23: 1178–1186.

Saison J, Costedoat-Chalumeau N, Maucort-Boulch D, Iwaz J, Marignier R, Cacoub P et al. Systemic lupus erythematosus-associated acute transverse myelitis: manifestations, treatments, outcomes, and prognostic factors in 20 patients. Lupus 2015; 24: 74–81.

Bombardier C, Gladman DD, Urowitz MB, Caron D, Chang CH . Derivation of the SLEDAI. A disease activity index for lupus patients. The Committee on Prognosis Studies in SLE. Arthritis Rheum 1992; 35: 630–640.

Maynard FM Jr, Bracken MB, Creasey G, Ditunno JF Jr, Donovan WH, Ducker TB et al. International standards for neurological and functional classification of spinal cord injury. American Spinal Injury Association. Spinal Cord 1997; 35: 266–274.

Amato MP, Grimaud J, Achiti I, Bartolozzi ML, Adeleine P, Hartung HP et al. Evaluation of the EDMUS system (EVALUED) Study Group. European validation of a standardized clinical description of multiple sclerosis. J Neurol 2004; 251: 1472–1480.

Miyakis S, Lockshin MD, Atsumi T, Branch DW, Brey RL, Cervera R et al. International consensus statement on an update of the classification criteria for definite antiphospholipid syndrome (APS). J Thromb Haemost 2006; 4: 295–306.

Pittock SJ, Lennon VA, de Seze J, Vermersch P, Homburger HA, Wingerchuk DM et al. Neuromyelitis optica and non organ-specific autoimmunity. Arch Neurol 2008; 65: 78–83.

Wingerchuk DM, Weinshenker BG . The emerging relationship between neuromyelitis optica and systemic rheumatologic autoimmune disease. Mult Scler 2012; 18: 5–10.

Falgàs N, Sola-Valls N, Sepúlveda M, Lapuma D, Ariño H, Llufriu S et al. Longitudinally extensive myelitis in a patient with characteristic autoantibody profile of systemic lupus erythematosus: a challenging etiological diagnosis. Lupus 2014; 23: 1555–1556.

Bertsias GK, Ioannidis JP, Aringer M, Bollen E, Bombardieri S, Bruce IN et al. EULAR recommendations for the management of systemic lupus erythematosus with neuropsychiatric manifestations: report of a task force of the EULAR standing committee for clinical affairs. Ann Rheum Dis 2010; 69: 2074–2082.

Barile-Fabris L, Ariza-Andraca R, Olguín-Ortega L, Jara LJ, Fraga-Mouret A, Miranda-Limón JM et al. Controlled clinical trial of IV cyclophosphamide versus IV methylprednisolone in severe neurological manifestations in systemic lupus erythematosus. Ann Rheum Dis 2005; 64: 620–625.

Fernandes Moça Trevisani V, Castro AA, Ferreira Neves Neto J, Atallah AN . Cyclophosphamide versus methylprednisolone for treating neuropsychiatric involvement in systemic lupus erythematosus. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2013; 28: 2 CD002265.

Narváez J, Ríos-Rodriguez V, de la Fuente D, Estrada P, López-Vives L, Gómez-Vaquero C et al. Rituximab therapy in refractory neuropsychiatric lupus: current clinical evidence. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2011; 41: 364–372.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Hryb, J., Chiganer, E., Contentti, E. et al. Myelitis in systemic lupus erythematosus: clinical features, immunological profile and magnetic resonance imaging of five cases. Spinal Cord Ser Cases 2, 16005 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/scsandc.2016.5

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/scsandc.2016.5

This article is cited by

-

Atypical Pediatric Demyelinating Diseases of the Central Nervous System

Current Neurology and Neuroscience Reports (2019)