Abstract

Study design:

Prospective observational-analytical study.

Objectives:

Description of diffusion tensor imaging (DTI) metrics obtained from the spinal cord (SC) of dogs with severe acute or chronic spontaneous, non-experimentally induced spinal cord injury (SCI) and correlation of DTI values with lesion extent of SCI measured in T2-weighted (T2W) magnetic resonance imaging sequences.

Setting:

Hannover, Germany.

Methods:

Forty-seven paraplegic dogs, 32 with acute and 15 with chronic SCI, and 6 disease controls were included. T2W and DTI sequences of the thoracolumbar spinal cord were performed. Values of fractional anisotropy (FA) and apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC) were obtained from the epicentre of the lesion and one SC segment cranially and caudally and compared between groups. Pearson’s correlation coefficient was calculated between DTI and T2W metrics.

Results:

During acute SCI, FA values were increased (P=0.0065) and ADC values were decreased (P=0.0099) at epicentres compared to disease controls. FA values obtained from dogs with chronic SCI were lower (P<0.0001 epicentres and caudally; P=0.0002 cranially) and ADC showed no differences compared to disease control values. Dogs with chronic SCI revealed lower FA and higher ADC compared to dogs with acute SCI (P<0.0001 for both values at all localisations). FA values from epicentre and cranially to the lesion during chronic SCI correlated with extent of lesion (r=0.5517; P=0.0052 epicentres and r=0.6810; P=0.0408 cranially).

Conclusion:

Using DTI, differences between acute and chronic stages of spontaneous canine SCI were detected and correlations between T2W and DTI sequences were found in chronic SCI, supporting canine SCI as a useful large animal model.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Traumatic spinal cord injury (SCI) is a frequently occurring neurological condition that can lead to permanent loss of sensorimotor and visceral function.1 In Germany, the reported annual incidence of traumatic SCI varies from 10.65 to 36 individuals per million.2, 3, 4 Initial cellular destruction caused by direct mechanical damage is defined as primary injury.1 Seconds after primary injury occurs, dynamic and complex cellular responses take place, including cytokine production, excitotoxicity, inflammatory reactions and free radical release associated with variable extent of oedema and haemorrhage.1, 5, 6 Further intrinsic de- and regenerative response mechanisms to injury lead to a consolidation of an astrocyte-mediated glial scar.6, 7, 8 Such a cascade of dynamic events is known as the secondary degeneration.1, 9 Current assessment of the severity and extent of SCI encompasses evaluation of compression and intramedullary hyperintense signal in conventional T2-weighted (T2W) magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).10, 11, 12, 13, 14 Treatment for traumatic SCI includes decompression of the spinal cord and stabilisation of the vertebral column;15 nonetheless, specific therapy targeted to mitigate the effects of the secondary degeneration remains limited.1, 16, 17

Several animal models have been used to reproduce SCI and contribute to a better understanding of pathophysiological processes that take place during different temporal stages.8, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22 The most commonly used is the rodent model, as laboratory conditions enable low variability;1 however, the necessity of a large animal model has led to an increased recognition of canine model of spontaneous, that is, non-experimentally induced, SCI.23, 24, 25 Non-experimentally induced SCI in dogs is most commonly caused by intervertebral disc herniation (IVDH) and external blunt traumas.26, 27 Private-owned dogs (that is, non-experimental dogs) represent a realistic and challenging scenario, as these individuals may be affected by concomitant morbidities at the time of the SCI;28, 29, 30 moreover, veterinary clinicians are confronted with lack of objective prognostic tools and limited treatment possibilities for dogs affected by severe spontaneous SCI.30, 31 Acute extrusions of degenerated nucleus pulposus into the vertebral canal produce contusive—compressive forces concurrently damaging the spinal cord.23, 32 The pathogenesis implies a wide extent of variability concerning severity of clinical signs, localisation and degree of spinal cord compression,23, 33 resembling human traumatic SCI and representing a valuable opportunity to bridge the gap between rodents and humans.7, 24, 33

Diffusion tensor imaging (DTI) enables in vivo and non-invasive assessment of white matter tracts of the spinal cord.34 Microstructural barriers, such as myelin and cellular membranes of axonal tracts, facilitate a homogeneous and directionally dependent diffusion.35 Fractional anisotropy (FA) and apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC) are the most commonly evaluated diffusion metrics.36 FA is expressed as a unitless numerical scale, where FA equal to zero indicates a directionally unrestricted or equally restricted diffusion, whereas FA equal to one represents a completely restricted diffusion along a single axis.37, 38, 39 While FA expresses the direction of diffusion, ADC reflects the capacity and subsequently the magnitude of water molecules to diffuse in any given preferential direction.36, 38, 40, 41 Axonal tracts of the spinal cord represent a homogeneous anisotropic environment that facilitate diffusion of water molecules parallel rather than perpendicular to axons.42, 43 ADC and FA values are therefore influenced by pathological processes that could lead to changes in magnitude and directionality of water molecule diffusion, respectively, such as compression of the spinal cord, axonal disruption, demyelination, cytotoxic oedema and presence of Wallerian degeneration.44, 45

Assessment of human SCI using DTI has been primarily performed for the chronic stage of the disease,34, 46 probably due to the fact that time may represent a restraining factor limiting the number of MRI scans in patients with acute traumatic SCI. There is therefore a need for DTI studies during the acute stage of DTI in both, humans and animal models.47, 48, 49, 50 Little is known about in vivo diffusion behaviour after severe SCI comparing acute and chronic stages, being mostly reported in rodents showing some degree of motor function recovery and therefore omitting a population of animals having an unfavourable prognosis.51, 52, 53

The aim of this study is to describe diffusion metrics obtained from the spinal cord of paraplegic dogs with acute or chronic SCI using a clinically applicable DTI protocol and to correlate DTI values with lesion extent of SCI measured in conventional T2W sequences. We hypothesise (1) that DTI is capable of detecting microstructural differences between acute and chronic SCI; and (2) that values obtained from the spinal cord of paraplegic dogs suffering chronic SCI will show a more isotropic diffusion and longer lesion extent in T2W sequences compared to paraplegic dogs with acute SCI.

Methods

Dog population

For the present study, paraplegic dogs admitted to the Department of Small Animal Medicine and Surgery, University of Veterinary Medicine Hannover, were prospectively recruited. Dogs with paraplegia due to SCI with or without presence of deep pain perception (DPP), a neuroanatomical localisation of the spinal cord lesion in the T3-L3 segments and a body weight less than 20 kg were included. Further tests comprised physical and neurological examinations, radiographs of the vertebral column, blood cell count and serum biochemistry analysis, urinalysis, MRI of the thoracolumbar segment of the spinal cord, and cerebrospinal fluid examination. Intact DPP was defined as a targeted behavioural response (such as whining, turning the head towards the stimulus or attempting to bite) after clamping the distal phalanges of the hind limbs with forceps.31, 54

SCI in dogs occurs spontaneously, commonly caused by IVDH or vehicular accidents.6 Time of initial SCI had therefore to be defined as the time point of non-ambulatory state first noticed by the owners.31 Paraplegic dogs were assigned into two different groups with regard to the time point of neurological and MRI examinations in the clinic: the acute SCI group (⩽7 days) and the chronic SCI group (⩾28 days).8, 55, 56 Moreover, MRI sequences from six previously reported dogs, five males and one female, with either orthopaedic disease or neurological signs localised outside the T3-L3 segments of the spinal cord were included as disease controls.57 Their mean age was 6.4 years (median, 6.5 years; range, 1.7–12.1 years) and their mean body weight 15.6 kg (median, 11.8 kg; range, 6–30 kg). This study was performed according to the German animal welfare statutes (Number: 33.9-42502-04-11/0661) and the written consent of the dog owners for each examination.

Image acquisition

MRI scans were performed under general anaesthesia and assisted ventilation and dogs were positioned in dorsal recumbency to avoid movement artefacts.58 A sensitivity-encoding (SENSE) spinal coil with 15 channels was used. Transversal and sagittal Turbo-Spin-Echo T2W as well as single-shot Echo-Planar-Imaging DWI SE sequences of the thoracolumbar spinal cord were performed in all dogs using a 3T MRI scanner (Phillips Achieva, Eindhoven, the Netherlands).

The protocol used for acquisition of sagittal T2W images consisted of repetition time (TR) between 3100 and 4786.4 ms, 120 ms echo time (ET), field of view (FOV) between 260.7 and 392.0 mm, a slice thickness of 1.8 mm and a space between slices of 0.2 mm. Furthermore, transversal T2W sequences were acquired using TR between 5472.2 and 9681.7 ms, ET of 120 ms, FOV of 190 mm, slice thickness of 2 mm and a space between slices of 0.2 mm.

Regarding DTI sequences, the protocol had an acquisition matrix of 108 × 98, FOV of 214 mm and 70 ms ET. TR varied between 2758 and 11 713 ms depending on slice number adapted according to the dog’s size. Slice number varied from 42 to 110. Moreover, 32 diffusion directions were applied (applied diffusion weighting (b value) low b value=0, maximal b value=800 s mm−2). Furthermore, reconstructed voxel size was determined for 1.65 × 1.65 × 2.00 mm, slice thickness was fixed in 2 mm and no space was left between slices. Phase correction was automatically applied during acquisition of DTI sequences and spectral pre-saturation with inversion recovery, a spin manipulation involving fat with no effect on water resonance, was implemented in order to diminish interference from epidural fat. Moreover, dynamic stabilisation was used at acquisition time point to improve image consistency and for motion correction. Using a diffusion registration package, DTI images were intra-registered to the baseline b=0 value scans to correct eddy-current distortions.57, 59, 60, 61

Image processing

T2W sequences were examined by at least one board certified neurologist (AT and/or VMS) in order to determine localisation of lesion and presence of spinal cord compression. Moreover, assessment of lesion extent of SCI was performed in sagittal T2W planes, as this method is currently used for evaluation of lesion extent and severity in clinical conditions.12, 25, 55, 56, 62 Lesion extent of the spinal cord in T2W sequences was defined as segments presenting herniated disc material causing compression of the spinal cord and associated intramedullary hyperintense signal.25, 62 Extent of spinal cord lesion was assessed in sagittal T2W images. Lengths of hyperintense signal and spinal cord compression were measured in millimetres and expressed as a ratio in relation to the vertebral body length of the second lumbar vertebra as previously described and defined as T2W lesion extent ratio (T2W-LER; Figure 1).25, 62 Evaluation of T2W-LER was performed using the commercially available software easyVET (Version 8.0.0.03/R3, 2015, Isernhagen, Germany).

Sagittal plane T2W images from the spinal cord of a male Jack Russell Terrier, age 4.4 years and body weight 7.4 kg with an acute SCI due to IVDH at the level of Th12/13 (white star; a) and a male Dachshund, age 4.8 years and body weight 8.8 kg affected by a chronic SCI caused by IVDH at Th11/12 (b). Length of vertebral body L2 and T2W lesion extent are shown with green lines.

Definition of the regions of interest (ROI) in DTI sequences was performed using the extended MR workspace software (Version 2.6.3.4, 2012, Philips Medical Systems, Eindhoven, the Netherlands). For this purpose, T2W images were placed over FA maps serving as template for determination and positioning of the ROIs. In dogs affected by acute or chronic SCI, values of FA and ADC were obtained from ROIs placed within signal deriving from spinal cord at the epicentre, as well as one spinal segment cranially and caudally. In dogs presented with an acute SCI, the epicentres were defined as segments of spinal cord with contusion and/or compression caused by IVDH or vertebral fracture; whereas in dogs presented with chronic SCI, epicentres were defined as spinal cord segments with compression or evidence of previous surgical decompression suggesting the initial localisation of SCI. In FA maps, signal deriving from spinal cord parenchyma above intervertebral disc spaces was first identified. Herniated disc material and fluid filled cavitations were identified when present and excluded from measurements; therefore, only signal from spinal cord parenchyma was taken into consideration for ROI placement (Figure 2). Individual voxels were first placed within the white and grey matter of the spinal cord using the application tool ‘Multiple ROIs’ avoiding signals representing cerebrospinal fluid and epidural fat. Voxels were set in transversal FA maps to minimise partial volume effects.58

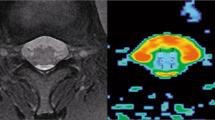

Transversal planes of T2W and diffusion tensor imaging—FA maps of the spinal cord from (a) a male Dachshund age 9.7 years and body weight 14.8 kg, with an acute SCI after IVDH at the level of L1/2, and (b) a female French bulldog, age 2.8 years and body weight 13 kg, with a chronic SCI at the level of L2/3. Colour coding of FA maps denote water diffusion in cranio-caudal axis in blue, in latero-lateral axis in red and in ventro-dorsal axis in green. The star in a shows disc material compressing the spinal cord and arrows in b point at cavitations within the spinal cord. Areas considered for placement of ROIs are delimitated by a white contour.

Statistical analysis

FA and ADC values obtained from dogs that required positioning of more than one ROI at the lesion epicentre were reported as mean values. Similarly, in disease control dogs, mean values of DTI metrics obtained from at least two localisations between T12 and L3 segments were calculated. Assumption of normal distribution of DTI values was tested by means of Kolmogorov-Smirnov test as well as visual evaluation of qq-plots of model residuals. Moreover, a one-way variance analysis was performed to compare DTI metrics between groups at each independent spinal localisation and additionally, the effect of sex on variance analysis was evaluated as a dichotomous variable. Furthermore, covariance calculations to assess influence of either age or body weight over FA and ADC values were additionally implemented for each variance analysis. Student’s t-tests were performed to compare T2W-LER between acute and chronic SCI affected dogs. Correlations between DTI values and T2W-LER obtained from paraplegic dogs were determined by means of a Pearson’s correlation coefficient. Significance level was set at P<0.05, statistics were performed using SAS software, version 9.2 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA) and graphics were generated utilising the commercial software GraphPad Prism (version 5, GraphPad Software, CA, USA).

Results

Population

A total of 47 paraplegic dogs with thoracolumbar SCI, 28 males and 19 females, fulfilled the inclusion criteria. Mean age was 5.7 years (median, 4.8 years; range, 2–16 years) and mean body weight was 9.1 kg (median, 8.8 kg; range, 3.8–19.6 kg; detailed information of subjects is contained in Table 1). Thirty-two dogs were assigned to the group of acute SCI (time point of non-ambulatory state first noticed by the owners to examination ⩽7 days; mean, 1.4 days; median, 1 day; range, 0–7 days), whereas 15 dogs were assigned to the chronic SCI group (time point of non-ambulatory state first noticed by the owners to examination ⩾28 days; mean, 167.1 days; median, 136 days; range, 53–365 days). In three dogs belonging to the chronic SCI group, it was not possible to determine the exact time point of initial trauma precisely as dogs came from animal shelters. Furthermore, the age could not be determined in one of these dogs for the same reason. All dogs with an acute SCI were diagnosed with IVDH, with the exception of one dog with a vertebral fracture following exogenous trauma. Eleven dogs with chronic SCI had evidence of former decompressive surgery due to IVDH.

Fractional anisotropy

Measured FA values are summarised in Table 2. At the epicentres, values measured from the group of dogs with acute SCI were higher than of disease control dogs (P=0.0065); furthermore, no difference was found perilesionally between the group with acute SCI and disease controls (P=0.2054 cranially and P=0.4968 caudally to epicentre; Figure 3). Moreover, FA values from the group of dogs with chronic SCI dogs were significantly lower when compared to disease control dogs (P<0.0001 at epicentres and caudally; P=0.0002 cranially; Figure 3). Comparison of dogs with acute or chronic SCI revealed a highly significant difference at each spinal cord localisation in respect to the lesion (P<0.0001 at epicentres, cranially and caudally; Figure 3). Covariance analysis performed between chronic SCI, acute SCI and disease control groups revealed no influence of sex (P=0.1695 at epicentres, P=0.1663 cranially and P=0.6012 caudally), body weight (P=0.8938 at epicentres, P=0.8956 cranially and P=0.8816 caudally) or age (P=0.5489 at epicentres, P=0.7151 cranially and P=0.7734 caudally) among any of the groups on the variance analysis.

Tukey box plots depicting distribution of FA values obtained from paraplegic dogs after acute and chronic SCI at each evaluated spinal cord segment in relation to the lesion. Second quartile, median and third quartile of FA obtained from disease control dogs are depicted in the background as a grey area and horizontal line, respectively. Significance levels between dogs with acute and chronic SCI are shown with stars (*), whereas significance level between acute or chronic SCI affected dogs and disease controls are depicted with numerical signs (#).

Measured FA values are summarised in Table 2. Comparison of dogs with acute or chronic SCI revealed a highly significant difference at each spinal cord localisation in respect to the lesion (P<0.0001 at epicentres, cranially and caudally; Figure 3). Moreover, FA values from the group of dogs with chronic SCI dogs were significantly lower when compared to disease control dogs (P<0.0001 at epicentres and caudally; P=0.0002 cranially; Figure 3). At the epicentres, values measured from the group of dogs with acute SCI were higher than of disease control dogs (P=0.0065); furthermore, no difference was found perilesionally between the group with acute SCI and disease controls (P=0.2054 cranially and P=0.4968 caudally to epicentre; Figure 3).

Covariance analysis performed between chronic SCI, acute SCI and disease control groups revealed no influence of sex (P=0.1695 at epicentres, P=0.1663 cranially and P=0.6012 caudally), body weight (P=0.8938 at epicentres, P=0.8956 cranially and P=0.8816 caudally) or age (P=0.5489 at epicentres, P=0.7151 cranially and P=0.7734 caudally) among any of the groups on the variance analysis.

Apparent diffusion coefficient

ADC values are summarised in Table 2. Values obtained from epicentres in dogs suffering from acute SCI differed from disease control values, being significantly lower (P=0.0099). Decrease in ADC values was, however, not present in segments cranial and caudal to epicentres (P=0.4546 cranial and P=0.1153 caudal to epicentre; Figure 4) Interestingly, no significant differences of ADC values were found between paraplegic dogs with a chronic state of SCI and disease control values at any localisation (P=0.1436 epicentres, P=0.1348 cranially and P=0.1794 caudally). Paraplegic dogs suffering from acute SCI had significantly lower ADC values at each localisation compared to those with chronic SCI (P<0.0001 for epicentres, cranially and caudally; Figure 4). Neither sex (P=0.2778 at epicentres, P=0.4739 cranially and P=0.6302 caudally), body weight (P=0.3202 epicentres, P=0.1266 cranially and P=0.2885 caudally) nor age (P=0.1818 epicentres, P=0.5059 cranially and P=0.8419) had an influence on ADC values among the different groups at each evaluated spinal cord segment.

Tukey box plots depicting distribution of ADC values obtained from paraplegic dogs after acute and chronic SCI at each evaluated spinal cord segment in respect to the lesion. Second quartile, median and third quartile of ADC obtained from disease control dogs are depicted in the background as a grey area and horizontal line, respectively. Significance levels between acute and chronic SCI affected dogs are shown with stars (*) and significance level between acute or chronic SCI affected dogs and disease controls are depicted with numerical signs (#).

ADC values are summarised in Table 2. Paraplegic dogs suffering from acute SCI had significantly lower ADC values at each localisation compared to those with chronic SCI (P<0.0001 for epicentres, cranially and caudally; Figure 4). Values obtained from epicentres in dogs suffering from acute SCI differed from disease control values, being significantly lower (P=0.0099). Decrease in ADC values was, however, not present in segments cranial and caudal to epicentres (P=0.4546 cranial and P=0.1153 caudal to epicentre; Figure 4). Interestingly, no significant differences of ADC values were found between paraplegic dogs with a chronic state of SCI and disease control values at any localisation (P=0.1436 epicentres, P=0.1348 cranially and P=0.1794 caudally). Neither sex (P=0.2778 at epicentres, P=0.4739 cranially and P=0.6302 caudally), body weight (P=0.3202 epicentres, P=0.1266 cranially and P=0.2885 caudally) nor age (P=0.1818 epicentres, P=0.5059 cranially and P=0.8419) had an influence on ADC values among the different groups at each evaluated spinal cord segment.

T2W to lesion extent ratio

T2W-LER in the acute SCI group displayed a mean value of 3.89 (s.e.m.±0.3493; median, 3.26), whereas the chronic group showed a mean value of 5.96 (s.e.m.±0.7918; median, 5.60). Dogs with chronic SCI had significantly higher T2W-LER than those acutely affected (P=0.0077).

Moreover, results of Pearson’s correlation tests revealed a moderate negative correlation between T2W-LER and FA values obtained from dogs with acute and chronic SCI at the level of epicentres and one spinal cord segment cranially and a weak positive correlation between T2W-LER and ADC at the same localisations.

Correlations could not be found between both, FA and ADC, and T2W-LER in paraplegic dogs with acute SCI (Table 3 and Supplementary Fig. 1). However, a strong negative correlation and a moderate negative correlation was found between T2W-LER and FA values at the level of one spinal cord segment cranially to epicentres and at epicentres, respectively. ADC values and T2W-LER did not correlate in the chronic stage of SCI (Table 3).

Discussion

In the present study, DTI values measured from the thoracolumbar spinal cord of a population of paraplegic dogs with acute or chronic SCI were characterised and compared. Lesions to the spinal cord in this study were not experimentally induced in laboratory conditions, but dogs were prospectively recruited as they spontaneously developed paraplegia.

In dogs with chronic SCI, FA values were lower than in both, disease controls and dogs with an acute SCI at all spinal cord localisations evaluated. Chronic state of SCI is the result of complex adaptation responses engaging vascular changes, free radical formation, ionic imbalances, inflammation, demyelination and apoptosis.1, 63, 64 Such mechanisms facilitate gliosis, activation of astrocytes and subsequent formation of intraparenchymal fluid-filled cavitations through glial scar consolidation together with partial remyelination and large spaces between axons.6, 8, 24 Consequently, massive loss of white matter tracts may cause decreases in anisotropy, which are reflected by a decrease of FA values (Figure 5). Low anisotropy is the hallmark of chronic SCI in humans and rodents as well.51, 53, 65, 66, 67 Furthermore, secondary degeneration-mediated lesions extending cranially and caudally from lesion epicentre lead in some cases to myelomalacia, fluid cavity formation and Wallerian degeneration.7, 45, 63, 68 Lower perilesional FA values in paraplegic dogs affected by chronic SCI are in agreement with former observations in distant spinal cord segments of humans suffering chronic SCI.45

Schematic representation of diffusion tensor ellipsoids in the canine spinal cord of disease controls (a), and in lesion epicentre during acute contusive-compressive (b) and chronic SCI (c). Axonal swelling and mechanical compression during acute SCI causes a highly anisotropic environment with diffusion magnitude impairment. Chronic SCI is characterised by unrestricted diffusion directionality and magnitude due to loss of axonal tracts, demyelination and Wallerian degeneration (Figure modified according to Anwar et al.81).

Dogs affected by acute SCI showed increased FA values at the lesion epicentre compared to disease controls. This finding is opposed to reported FA values of rodents after contusion, hemitransection or transection of the spinal cord.50, 51, 52, 69 In contrast to most rodent models, which use contusion injury alone with no compression, spontaneous canine SCI combines contusion and permanent compression forces exerted over the spinal cord.24, 32 Presence of extruded disc material in the vertebral canal at the level of epicentres may cause a reduction of space, and therefore the risk of compression, between intact or swollen axonal tracts increasing its anisotropy (Figure 5). Increased FA values are commonly reported in acute traumatic brain injury in humans and cytotoxic oedema in white matter tracts has been postulated as a possible cause.70, 71

ADC revealed a wider distribution than FA in dogs with acute and chronic SCI. In a study describing healthy canine spinal cords, ADC values showed more variability among individuals and localisations than FA.58 In the current study, ADC values obtained at epicentres and perilesional differed significantly between the acute and chronic states of SCI. However, these values did not reach significance levels when compared to disease control dogs, with the exception of ADC metrics measured at epicentres during acute SCI. Spheroid formation as well as intra-axonal mitochondrial accumulations and permanent mechanical deformation by extruded disc material during the acute state of injury may explain the impaired diffusivity found at the epicentre (Figure 5).6, 7 A clear differentiation of the compressed spinal cord’s white and grey matter is challenging, even when evaluating conventional T2W sequences. Therefore, no attempt was made to distinguish individual funiculi and signal deriving from whole parenchyma was considered for ROI placement as previously reported.57, 58, 72

In conventional T2W sequences, SCI can be evidenced by the presence of compression and/or intramedullary hyperintense signal.10, 11, 12, 14 Intramedullary T2W hyperintensities have been associated with oedema, haemorrhage, malacia, necrosis, liquefaction and fluid-filled cavitations.8, 73, 74 As expected, dogs with acute SCI showed a lower T2W-LER than dogs from the chronic group, since progression of the secondary degeneration may induce microstructural and MRI signal intensity changes as evidenced in perilesional and distant segments.7, 75, 76 Interestingly, lower values of FA obtained from lesion epicentres and one spinal cord segment cranially were correlated with longer T2W-LER in the chronic group, suggesting that Wallerian degeneration and enlarged space between axonal tracts and glial scar most commonly occur caudal to the lesion epicentre, and as the lesion extends, cranial segments are involved. Similar, in humans, extent of retrograde Wallerian degeneration during chronic SCI has been evidenced in axonal tracts of the dorsal column cranial to the epicentre.11, 76, 77, 78 Quantifiable data for structural integrity obtained through DTI of the spinal cord could complement visual assessment of T2W sequences and provide greater insight into the nature of the lesion. This may be particularly important in clinical decision making situations.

As DTI of the spinal cord has been scarcely described in animal models with spontaneous SCI,42 our first aim was to characterise both temporal stages of SCI in dogs. This study validates the use of DTI technique in acute and chronic SCI in dogs, a tool which was formerly reported in healthy dogs.57, 58, 79 Private-owned dogs with SCI represent a very unique study population mirroring circumstances present in human SCI, as many of them may present co-morbidities at the time point of the SCI and may be affected from post-injury complications such as recurrent urinary bladder infections.30, 80 Moreover, dogs affected by spontaneous SCI are often managed long term by their owners albeit absent or incomplete functional recovery.30 In contrast to what has been reported in rodents with experimentally induced SCI, the fact that DTI metrics behave differently between acute and chronic stages in a spontaneous model of SCI opens the window for further research opportunities such as correlations regarding outcome, motor functional recovery and prognostic value of DTI for clinical trials that could potentially benefit both, humans and dogs affected with severe SCI.

Diffusion tensor MR was able to determine microstructural differences between acute and chronic stages of SCI, particularly regarding parenchymal anisotropy depicted by the FA value. Furthermore, FA values correlated with T2W-LER in chronic SCI. These findings suggest that measurements of FA are a promising complementary monitoring tool for microstructural evaluation of the spinal cord in dogs with chronic SCI for novel treatment implementation and emphasise the role of spontaneous canine SCI as a large animal translational model for human SCI.

Data archiving

There were no data to deposit.

References

Silva NA, Sousa N, Reis RL, Salgado AJ . From basics to clinical: a comprehensive review on spinal cord injury. Prog Neurobiol 2014; 114: 25–57.

Koning W, Frowein RA . Incidence of spinal cord injury in the Federal Republic of Germany. Neurosurg Rev 1989; 12 (Suppl 1): 562–566.

Exner G, Meinecke FW . Trends in the treatment of patients with spinal cord lesions seen within a period of 20 years in German centers. Spinal Cord 1997; 35: 415–419.

Lee BB, Cripps RA, Fitzharris M, Wing PC . The global map for traumatic spinal cord injury epidemiology: update 2011, global incidence rate. Spinal Cord 2014; 52: 110–116.

Witiw CD, Fehlings MG . Acute spinal cord injury. J Spinal Disorders Tech 2015; 28: 202–210.

Smith PM, Jeffery ND . Histological and ultrastructural analysis of white matter damage after naturally-occurring spinal cord injury. Brain Pathol 2006; 16: 99–109.

Bock P, Spitzbarth I, Haist V, Stein VM, Tipold A, Puff C et al. Spatio-temporal development of axonopathy in canine intervertebral disc disease as a translational large animal model for nonexperimental spinal cord injury. Brain Pathol 2013; 23: 82–99.

Hu R, Zhou J, Luo C, Lin J, Wang X, Li X et al. Glial scar and neuroregeneration: histological, functional, and magnetic resonance imaging analysis in chronic spinal cord injury. J Neurosurg Spine 2010; 13: 169–180.

Oyinbo CA . Secondary injury mechanisms in traumatic spinal cord injury: a nugget of this multiply cascade. Acta Neurobiol Exp 2011; 71: 281–299.

Yamashita Y, Takahashi M, Matsuno Y, Sakamoto Y, Oguni T, Sakae T et al. Chronic injuries of the spinal cord: assessment with MR imaging. Radiology 1990; 175: 849–854.

Becerra JL, Puckett WR, Hiester ED, Quencer RM, Marcillo AE, Post MJ et al. MR-pathologic comparisons of wallerian degeneration in spinal cord injury. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 1995; 16: 125–133.

Bodley R . Imaging in chronic spinal cord injury—indications and benefits. Eur J Radiol 2002; 42: 135–153.

McDonald JW, Sadowsky C . Spinal-cord injury. Lancet 2002; 359: 417–425.

Lammertse D, Dungan D, Dreisbach J, Falci S, Flanders A, Marino R et al. Neuroimaging in traumatic spinal cord injury: an evidence-based review for clinical practice and research. J Spinal Cord Med 2007; 30: 205–214.

Fehlings MG, Perrin RG . The role and timing of early decompression for cervical spinal cord injury: update with a review of recent clinical evidence. Injury 2005; 36 (Suppl 2): B13–B26.

Granger N, Franklin RJ, Jeffery ND . Cell therapy for spinal cord injuries: what is really going on? Neuroscientist 2014; 20: 623–638.

Raspa A, Pugliese R, Maleki M, Gelain F . Recent therapeutic approaches for spinal cord injury. Biotechnol Bioeng 2016; 113: 253–259.

Streijger F, Lee JH, Manouchehri N, Okon EB, Tigchelaar S, Anderson L et al. The evaluation of magnesium chloride within a polyethylene glycol formulation in a porcine model of acute spinal cord injury. J Neurotrauma 2016; 33: 2202–2216.

Jiang H, Wang J, Xu B, Yang H, Zhu Q . A model of acute central cervical spinal cord injury syndrome combined with chronic injury in goats. Eur Spine J 2016; 26: 56–63.

Ma Z, Zhang YP, Liu W, Yan G, Li Y, Shields LB et al. A controlled spinal cord contusion for the rhesus macaque monkey. Exp Neurol 2016; 279: 261–273.

Szarek D, Marycz K, Lis A, Zawada Z, Tabakow P, Laska J et al. Lizard tail spinal cord: a new experimental model of spinal cord injury without limb paralysis. FASEB J 2016; 30: 1391–1403.

Granger N, Blamires H, Franklin RJ, Jeffery ND . Autologous olfactory mucosal cell transplants in clinical spinal cord injury: a randomized double-blinded trial in a canine translational model. Brain 2012; 135 (Pt 11): 3227–3237.

Jeffery ND, Smith PM, Lakatos A, Ibanez C, Ito D, Franklin RJ . Clinical canine spinal cord injury provides an opportunity to examine the issues in translating laboratory techniques into practical therapy. Spinal Cord 2006; 44: 584–593.

Levine JM, Levine GJ, Porter BF, Topp K, Noble-Haeusslein LJ . Naturally occurring disk herniation in dogs: an opportunity for pre-clinical spinal cord injury research. J Neurotrauma 2011; 28: 675–688.

Boekhoff TM, Flieshardt C, Ensinger EM, Fork M, Kramer S, Tipold A . Quantitative magnetic resonance imaging characteristics: evaluation of prognostic value in the dog as a translational model for spinal cord injury. J Spinal Disorders Tech 2012; 25: E81–E87.

Fluehmann G, Doherr MG, Jaggy A . Canine neurological diseases in a referral hospital population between 1989 and 2000 in Switzerland. J Small Anim Pract 2006; 47: 582–587.

Priester WA . Canine intervertebral disc disease—occurrence by age, breed, and sex among 8,117 cases. Theriogenology 1976; 6: 293–303.

Jeffery ND, Hamilton L, Granger N . Designing clinical trials in canine spinal cord injury as a model to translate successful laboratory interventions into clinical practice. Vet Rec 2011; 168: 102–107.

Hoffman AM, Dow SW . Concise review: stem cell trials using companion animal disease models. Stem Cells 2016; 34: 1709–1729.

Moore SA, Granger N, Olby NJ, Spitzbarth I, Jeffery ND, Tipold A et al. Targeting translational successes through CANSORT-SCI: using pet dogs to identify effective treatments for spinal cord injury. J Neurotrauma 2017; 34: 2007–2018.

Jeffery ND, Barker AK, Hu HZ, Alcott CJ, Kraus KH, Scanlin EM et al. Factors associated with recovery from paraplegia in dogs with loss of pain perception in the pelvic limbs following intervertebral disk herniation. J Am Vet Med Assoc 2016; 248: 386–394.

Jeffery ND, Levine JM, Olby NJ, Stein VM . Intervertebral disk degeneration in dogs: consequences, diagnosis, treatment, and future directions. J Vet Intern Med 2013; 27: 1318–1333.

Olby N, Harris T, Burr J, Munana K, Sharp N, Keene B . Recovery of pelvic limb function in dogs following acute intervertebral disc herniations. J Neurotrauma 2004; 21: 49–59.

Martin AR, Aleksanderek I, Cohen-Adad J, Tarmohamed Z, Tetreault L, Smith N et al. Translating state-of-the-art spinal cord MRI techniques to clinical use: a systematic review of clinical studies utilizing DTI, MT, MWF, MRS, and fMRI. NeuroImage Clin 2016; 10: 192–238.

Hendrix P, Griessenauer CJ, Cohen-Adad J, Rajasekaran S, Cauley KA, Shoja MM et al. Spinal diffusion tensor imaging: a comprehensive review with emphasis on spinal cord anatomy and clinical applications. Clin Anat 2015; 28: 88–95.

Guan X, Fan G, Wu X, Gu G, Gu X, Zhang H et al. Diffusion tensor imaging studies of cervical spondylotic myelopathy: a systemic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE 2015; 10: e0117707.

Jellison BJ, Field AS, Medow J, Lazar M, Salamat MS, Alexander AL . Diffusion tensor imaging of cerebral white matter: a pictorial review of physics, fiber tract anatomy, and tumor imaging patterns. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2004; 25: 356–369.

Chagawa K, Nishijima S, Kanchiku T, Imajo Y, Suzuki H, Yoshida Y et al. Normal values of diffusion tensor magnetic resonance imaging parameters in the cervical spinal cord. Asian Spine J 2015; 9: 541–547.

Lerner A, Mogensen MA, Kim PE, Shiroishi MS, Hwang DH, Law M . Clinical applications of diffusion tensor imaging. World Neurosurg 2014; 82: 96–109.

Li XF, Yang Y, Lin CB, Xie FR, Liang WG . Assessment of the diagnostic value of diffusion tensor imaging in patients with spinal cord compression: a meta-analysis. Braz J Med Biol Res 2016; 49: e4769.

Soares JM, Marques P, Alves V, Sousa N . A hitchhiker's guide to diffusion tensor imaging. Front Neurosci 2013; 7: 31.

Vedantam A, Jirjis MB, Schmit BD, Wang MC, Ulmer JL, Kurpad SN . Diffusion tensor imaging of the spinal cord: insights from animal and human studies. Neurosurgery 2014; 74: 1–8.

Sasiadek MJ, Szewczyk P, Bladowska J . Application of diffusion tensor imaging (DTI) in pathological changes of the spinal cord. Med Sci Monit 2012; 18: Ra73–Ra79.

Shanmuganathan K, Gullapalli RP, Zhuo J, Mirvis SE . Diffusion tensor MR imaging in cervical spine trauma. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2008; 29: 655–659.

Kamble RB, Venkataramana NK, Naik AL, Rao SV . Diffusion tensor imaging in spinal cord injury. Indian J Radiol Imaging 2011; 21: 221–224.

Wheeler-Kingshott CA, Stroman PW, Schwab JM, Bacon M, Bosma R, Brooks J et al. The current state-of-the-art of spinal cord imaging: applications. Neuroimage 2014; 84: 1082–1093.

Kim JH, Loy DN, Wang Q, Budde MD, Schmidt RE, Trinkaus K et al. Diffusion tensor imaging at 3 hours after traumatic spinal cord injury predicts long-term locomotor recovery. J Neurotrauma 2010; 27: 587–598.

Kelley BJ, Harel NY, Kim CY, Papademetris X, Coman D, Wang X et al. Diffusion tensor imaging as a predictor of locomotor function after experimental spinal cord injury and recovery. J Neurotrauma 2014; 31: 1362–1373.

Yin B, Tang Y, Ye J, Wu Y, Wang P, Huang L et al. Sensitivity and specificity of in vivo diffusion-weighted MRI in acute spinal cord injury. J Clin Neurosci 2010; 17: 1173–1179.

Li XH, Li JB, He XJ, Wang F, Huang SL, Bai ZL . Timing of diffusion tensor imaging in the acute spinal cord injury of rats. Sci Rep 2015; 5: 12639.

Wang F, Huang SL, He XJ, Li XH . Determination of the ideal rat model for spinal cord injury by diffusion tensor imaging. Neuroreport 2014; 25: 1386–1392.

Zhao C, Rao JS, Pei XJ, Lei JF, Wang ZJ, Yang ZY et al. Longitudinal study on diffusion tensor imaging and diffusion tensor tractography following spinal cord contusion injury in rats. Neuroradiology 2016; 58: 607–614.

Jirjis MB, Kurpad SN, Schmit BD . Ex vivo diffusion tensor imaging of spinal cord injury in rats of varying degrees of severity. J Neurotrauma 2013; 30: 1577–1586.

Gorney AM, Blau SR, Dohse CS, Griffith EH, Williams KD, Lim JH et al. Mechanical and thermal sensory testing in normal chondrodystrophoid dogs and dogs with spinal cord injury caused by thoracolumbar intervertebral disc herniations. J Vet Intern Med 2016; 30: 627–635.

Levine JM, Fosgate GT, Chen AV, Rushing R, Nghiem PP, Platt SR et al. Magnetic resonance imaging in dogs with neurologic impairment due to acute thoracic and lumbar intervertebral disk herniation. J Vet Intern Med 2009; 23: 1220–1226.

Griffin JF, Davis MC, Ji JX, Cohen ND, Young BD, Levine JM . Quantitative magnetic resonance imaging in a naturally occurring canine model of spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord 2015; 53: 278–284.

Hobert MK, Stein VM, Dziallas P, Ludwig DC, Tipold A . Evaluation of normal appearing spinal cord by diffusion tensor imaging, fiber tracking, fractional anisotropy, and apparent diffusion coefficient measurement in 13 dogs. Acta Vet Scand 2013; 55: 36.

Griffin JFt, Cohen ND, Young BD, Eichelberger BM, Padua A Jr, Purdy D et al. Thoracic and lumbar spinal cord diffusion tensor imaging in dogs. J Magn Reson Imaging 2013; 37: 632–641.

Kwon YH, Son SM, Lee J, Bai DS, Jang SH . Combined study of transcranial magnetic stimulation and diffusion tensor tractography for prediction of motor outcome in patients with corona radiata infarct. J Rehabil Med 2011; 43: 430–434.

Chun KS, Lee YT, Park JW, Lee JY, Park CH, Yoon KJ . Comparison of diffusion tensor tractography and motor evoked potentials for the estimation of clinical status in subacute stroke. Ann Rehab Med 2016; 40: 126–134.

Jang SH, Kim SH, Jang WH . Recovery of corticospinal tract injured by traumatic axonal injury at the subcortical white matter: a case report. Neural Regen Res 2016; 11: 1527–1528.

Ito D, Matsunaga S, Jeffery ND, Sasaki N, Nishimura R, Mochizuki M et al. Prognostic value of magnetic resonance imaging in dogs with paraplegia caused by thoracolumbar intervertebral disk extrusion: 77 cases (2000-2003). J Am Vet Med Assoc 2005; 227: 1454–1460.

Mietto BS, Mostacada K, Martinez AM . Neurotrauma and inflammation: CNS and PNS responses. Mediat Inflamm 2015; 2015: 251204.

Hagg T, Oudega M . Degenerative and spontaneous regenerative processes after spinal cord injury. J Neurotrauma 2006; 23: 264–280.

Koskinen E, Brander A, Hakulinen U, Luoto T, Helminen M, Ylinen A et al. Assessing the state of chronic spinal cord injury using diffusion tensor imaging. J Neurotrauma 2013; 30: 1587–1595.

Cohen-Adad J, El Mendili MM, Lehericy S, Pradat PF, Blancho S, Rossignol S et al. Demyelination and degeneration in the injured human spinal cord detected with diffusion and magnetization transfer MRI. Neuroimage 2011; 55: 1024–1033.

Petersen JA, Wilm BJ, von Meyenburg J, Schubert M, Seifert B, Najafi Y et al. Chronic cervical spinal cord injury: DTI correlates with clinical and electrophysiological measures. J Neurotrauma 2012; 29: 1556–1566.

Henke D, Gorgas D, Doherr MG, Howard J, Forterre F, Vandevelde M . Longitudinal extension of myelomalacia by intramedullary and subdural hemorrhage in a canine model of spinal cord injury. Spine J 2016; 16: 82–90.

Patel SP, Smith TD, VanRooyen JL, Powell D, Cox DH, Sullivan PG et al. Serial diffusion tensor imaging in vivo predicts long-term functional recovery and histopathology in rats following different severities of spinal cord injury. J Neurotrauma 2016; 33: 917–928.

Eierud C, Craddock RC, Fletcher S, Aulakh M, King-Casas B, Kuehl D et al. Neuroimaging after mild traumatic brain injury: review and meta-analysis. NeuroImage Clin 2014; 4: 283–294.

Henry LC, Tremblay J, Tremblay S, Lee A, Brun C, Lepore N et al. Acute and chronic changes in diffusivity measures after sports concussion. J Neurotrauma 2011; 28: 2049–2059.

Mulcahey MJ, Samdani A, Gaughan J, Barakat N, Faro S, Betz RR et al. Diffusion tensor imaging in pediatric spinal cord injury: preliminary examination of reliability and clinical correlation. Spine 2012; 37: E797–E803.

Mihai G, Nout YS, Tovar CA, Miller BA, Schmalbrock P, Bresnahan JC et al. Longitudinal comparison of two severities of unilateral cervical spinal cord injury using magnetic resonance imaging in rats. J Neurotrauma 2008; 25: 1–18.

Byrnes KR, Fricke ST, Faden AI . Neuropathological differences between rats and mice after spinal cord injury. J Magn Reson Imaging 2010; 32: 836–846.

Gwak YS, Kang J, Unabia GC, Hulsebosch CE . Spatial and temporal activation of spinal glial cells: role of gliopathy in central neuropathic pain following spinal cord injury in rats. Exp Neurol 2012; 234: 362–372.

Kashani H, Farb R, Kucharczyk W . Magnetic resonance imaging demonstration of a single lesion causing Wallerian degeneration in ascending and descending tracts in the spinal cord. J Comput Assist Tomogr 2010; 34: 251–253.

Valencia MP, Castillo M . MRI findings in posttraumatic spinal cord Wallerian degeneration. Clin Imaging 2006; 30: 431–433.

Guleria S, Gupta RK, Saksena S, Chandra A, Srivastava RN, Husain M et al. Retrograde Wallerian degeneration of cranial corticospinal tracts in cervical spinal cord injury patients using diffusion tensor imaging. J Neurosci Res 2008; 86: 2271–2280.

Yoon H, Park NW, Ha YM, Kim J, Moon WJ, Eom K . Diffusion tensor imaging of white and grey matter within the spinal cord of normal Beagle dogs: sub-regional differences of the various diffusion parameters. Vet J 2016; 215: 110–117.

Olby NJ, Vaden SL, Williams K, Griffith EH, Harris T, Mariani CL et al. Effect of cranberry extract on the frequency of bacteriuria in dogs with acute thoracolumbar disk herniation: a randomized controlled clinical trial. J Vet Intern Med 2016; 31: 60–68.

Anwar MA, Al Shehabi TS, Eid AH . Inflammogenesis of secondary spinal cord injury. Front Cell Neurosci 2016; 10: 98.

Acknowledgements

We thank the ‘Gesellschaft der Freunde der Tierärztlichen Hochschule Hannover’ and the ‘Akademie für Tiergesundheit’ for financial support given to the first author. The present project was partly supported by the German Research Foundation (FOR 1103, project TI 309/4-2).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

FA and T2W-LER values from DTI scans of 32 dogs with acute SCI were used for the assessment of early functional recovery in another study. Statistic analysis and results conducted in this study were independently calculated and are not previously reported.

Additional information

Supplementary Information accompanies this paper on the Spinal Cord website

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Wang-Leandro, A., Hobert, M., Alisauskaite, N. et al. Spontaneous acute and chronic spinal cord injuries in paraplegic dogs: a comparative study of in vivo diffusion tensor imaging. Spinal Cord 55, 1108–1116 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/sc.2017.83

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sc.2017.83

This article is cited by

-

Outcomes of extensive hemilaminectomy with durotomy on dogs with presumptive progressive myelomalacia: a retrospective study on 34 cases

BMC Veterinary Research (2020)

-

The role of diffusion tensor imaging as an objective tool for the assessment of motor function recovery after paraplegia in a naturally-occurring large animal model of spinal cord injury

Journal of Translational Medicine (2018)

-

Magnetic resonance imaging features of dogs with incomplete recovery after acute, severe spinal cord injury

Spinal Cord (2018)