Abstract

The UK healthcare system faces a shortage of high-quality menopausal care. The objective of this study was to understand perspectives of menopause care in the UK. An online survey was delivered. Data from 952 respondents were analysed. Descriptive statistics were calculated for quantitative data overall and per menopause stage. Thematic analysis was calculated on qualitative data. 74.47% sought help for the menopause. Oral (68.83%) and topical medication (17.21%) and lifestyle changes (17.21%) were the most common treatment approaches. Consistent integration of mental health screening into menopausal care was lacking. Open-ended data from women who reported poor care quality revealed six themes: consequences of poor care, dismissive or negative attitudes from healthcare professionals (HCPs), poor treatment management, symptom information and misattribution, poor HCP knowledge, and the need for self-advocacy. The findings underscore the importance of improving HCP knowledge, providing empathetic and supportive care, and involving women in decision-making.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The menopause marks a substantial milestone in a woman’s life, which is characterised by the halt of menstruation owing to the decline of ovarian follicular function1 (throughout the current study, we refer to a woman as anyone assigned female at birth). It tends to occur naturally between the ages of 44 and 55 years2, but can be brought on earlier due to surgical procedures, medication, or severe illness3. The perimenopause, also referred to as the menopause transition, is defined as the phase leading up to menopause and is distinguished by a decline in ovarian function, leading to less frequent menstrual cycles. The perimenopause phase can be divided into two stages: the early perimenopause stage, which is characterised by a significant change in the length of menstrual bleed or the time between periods that is not due to pregnancy or breastfeeding, stress, or a medical condition, and the late perimenopause stage, which is defined by no menstrual bleeding in three to 11 months not due to pregnancy or breastfeeding, stress, or a medical condition. The perimenopause phase is estimated to last a median of four years4.

Although every woman’s experience of the menopause is unique, the symptoms that come with it and the transition leading up to it can be incredibly challenging. As many as 80% of women report difficulties during this time, with 25% rating these difficulties as severe5. Women who go through the menopause and its transition naturally may experience a range of vasomotor symptoms, such as hot flushes and night sweats, physical symptoms, including tiredness and bone and joint pain, as well as sexual symptoms, including loss of libido and vaginal dryness during intercourse. Though it has also been posited that only vasomotor symptoms are specific to the menopause, while other symptoms may be more strongly associated with socio-demographic variables6.

Of note, numerous studies have found a connection between menopausal symptoms and decreased quality of life, with a greater number of symptoms generally resulting in lower overall quality of life7,8,9,10,11,12. There is also evidence to suggest that, relative to natural menopause, women with medically induced menopause experience more severe menopausal symptoms and worse quality of life13,14. In turn, medically induced menopause has been associated with a range of long-term health consequences, including early onset cardiovascular disease, osteoporosis, dementia, and increased risk of mortality (or early death)15.

The menopause, and particularly the menopause transition, also present a period of heightened vulnerability for mental health issues16 especially depression17,18. Notably, perimenopausal women tend to report different symptoms of depression compared to premenopausal women, such as increased anger and irritability, sleep disturbances, fatigue, as well as a range of non-specific somatic complaints19. Interestingly, a systematic review involving over 10,000 menopausal women has revealed a bidirectional relationship between depressive and vasomotor symptoms20, with women experiencing moderate to severe depressive symptoms being nearly twice as likely to report vasomotor symptoms compared to those with no or mild depressive symptoms21. This suggests a potential aggravating effect of vasomotor symptoms on depressive symptoms22,23, although some propose that depression precedes hot flushes rather than being caused by them24.

Furthermore, women who have a history of depression or pre-existing physical health conditions are at a heightened risk of developing a depressive illness during this transitional phase25, and previous research has found a higher prevalence of depression among women with medically induced menopause compared to women who experience natural menopause26. Taken together, these findings pose important implications for healthcare professionals (HCPs) regarding the identification and management of mental health symptoms in women during the menopause and menopause transition, with routine mental health screening being crucial for early identification and intervention.

Undoubtedly, the menopause is a multifaceted phase that encompasses not only physical changes but also significant psychological challenges. Recognising the holistic nature of menopausal experiences is crucial for providing comprehensive care. In a systematic review examining perceptions of healthcare among immigrant women, most were dissatisfied with the care they had received27. Indeed, it is disheartening to note that menopausal care provision remains inadequate, even in high-income countries24. For instance, despite the monumental launch of the 2015 National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidelines for menopause care provision in the UK, the healthcare system continues to grapple with a lack of comprehensive and high-quality care for women28.

Critically, there is a notable gap in research regarding women’s first-hand experiences with menopausal care provision in the UK general population and it remains uncertain whether care experiences in the UK differ based on the specific stage of the menopause (i.e., early or late perimenopause stage versus the menopause) or for those experiencing medically induced menopausal symptoms. By gaining insights into women’s perspectives and challenges at different stages of the menopause and for those with medically induced menopause, we can develop a more patient-centred approach to menopausal care in the UK.

To this end, we set out to explore experiences with care provision throughout the menopause transition and the menopause offered via healthcare services in the UK using a mixed-methods approach. The key objective of this study was to understand women’s perspectives regarding the availability and quality of menopause care services in the UK, including care provision specifically for mental health concerns that may arise due to the menopause. In addition, we explored whether experiences with care provision vary across the perimenopause and the menopause, as well as for individuals with medically induced menopausal symptoms. The findings from this study have important implications for the development of future healthcare policies and guidelines and the improvement of the quality of care for women experiencing menopausal symptoms in the UK.

Results

Sociodemographic characteristics

Respondents’ sociodemographic information across the entire sample can be found in Fig. 1 and Supplementary Table 1A (Supplementary Materials). A total of 1154 participants commenced the survey, of which 82.50% (n = 952) completed at least 97% of the survey: early perimenopause stage (48.21%, n = 459), late perimenopause stage (17.54%, n = 167), post-menopause (26.05%, n = 248), and medically induced menopause (8.19%, n = 78) (Fig. 1A).

A Participant subgroup, B Education, C Employment, and D Household income. Key. A level, Advanced level qualification; GCSE, General Certificate of Secondary Education; IB, International Baccalaureate. a Percentages add up to more than 100% as respondents could select multiple options; b includes full-time employment (n = 450), part-time employment (n = 256), and self-employment (n = 105); c includes having an income of £15,000 or less (n = 69), between £15,001 and £25,000 (n = 76), and between £25,001 and £35,000 (n = 108); d includes having an income between £35,001 and £45,000 (n = 100), between £45,001 and £55,000 (n = 106), and between £55,001 and £65,000 (n = 90); e includes having an income between £65,001 and £75,000 (n = 90), between £75,001 and £85,000 (n = 65), and £85,001 or above (n = 137).

The average age across the entire sample (N = 952) was 50.01 (SD = 5.27, range=24–69), with the majority of respondents identifying with the female gender (98.00%, n = 933), being white (97.27%, n = 933), having at least an undergraduate degree (59.98%, n = 571), and being married or in a civil partnership (61.97%, n = 590) (Fig. 1B). Regarding accommodation characteristics, living with a partner and children (44.96%, n = 428) or living with a partner (33.82%, n = 322) were the most common arrangements. 85.19% (n = 811) were employed (Fig. 1C) and 61.76% (n = 588) had a household income of at least £35,001 before tax (Fig. 1D).

For a summary of between-group comparisons (i.e., early perimenopause stage, late perimenopause stage, post-menopause, medically induced menopause) on sociodemographic information see Supplementary Table 1A (Supplementary Materials). There was a significant between-group difference in age (F(3, 948) = 139.97, p < 0.001, η2 = 0.31), with those in the early perimenopause stage being younger (M = 47.16, SD = 4.21) than all other groups, and both respondents in the late perimenopause stage (M = 51.37, SD = 3.96) and medically induced menopause group (M = 51.18, SD = 6.20) being younger than the post-menopause group (M = 54.01, SD = 4.32). There was also a significant group difference in education level (H(3) = 10.21, p = 0.017). Respondents in the early perimenopause stage were more highly educated than the post-menopause group (U = 46030, p = 0.003, r = 0.11). Furthermore, there was a significant group difference in employment (χ²(3, N = 952) = 19.76, p < 0.001, φc = 0.14), with respondents in both the early perimenopause stage and post-menopause being less likely to be retired relative to those in the late perimenopause stage. No other significant group differences were found.

Healthcare provision throughout the menopause

Respondents’ healthcare provision across the entire sample can be found in Fig. 2 and Supplementary Table 1B (Supplementary Materials). Overall, the majority (74.47%, n = 709) of respondents had discussed their menopausal symptoms (e.g., hot flushes, mood changes, night sweats, irregular or absent periods, decreased sex drive) with a HCP (Fig. 2A), most frequently a National Health Service (NHS) GP (90.41%, n = 641), followed by a NHS gynaecologist (13.68%, n = 97), a private HCP (13.68%, n = 97), and other HCP (12.13%, n = 86; Fig. 2B). Of these, 78.56% (n = 557) expressed that they were aware that these symptoms were related to the menopause prior to their appointment with a HCP. For those who had visited a HCP for their menopause symptoms, the most common treatment or support options were oral (68.83%, n = 488) and topical medication (e.g., vaginal oestrogen creams) (17.21%, n = 122), as well as lifestyle changes (17.21%, n = 122) (Fig. 2C), with the majority (55.29%, n = 392) being prescribed these treatment or support options by their HCP (Fig. 2D). 18.76% (n = 133) of those who had visited a HCP for their menopausal symptoms had not received any treatment or support options (Fig. 2C). In terms of overall perceived quality of care for menopausal symptoms, 36.95% (n = 262) stated that they had received very good or good care, while 27.65% (n = 196) experienced acceptable care, and 35.40% (n = 251) expressed that they had received poor or very poor care.

A Consulted HCP for menopausal symptoms, B HCPs consulted, C Recognised menopause as cause of symptoms, and D Treatment or support for menopausal symptoms. Key. GP general practitioner, HCP healthcare professional, NHS National Healthcare Service. a Includes those who had visited a HCP for their menopausal symptoms (n = 709); bpercentages add up to more than 100% as respondents could select multiple options.

For a summary of between-group comparisons (i.e., early perimenopause stage, late perimenopause stage, post-menopause, medically induced menopause) on healthcare provision throughout the menopause see Supplementary Table 1B (Supplementary Materials). There was a significant group difference in the proportion of respondents who had seen a HCP for their menopausal symptoms (χ²(3, N = 952) = 18.61, p < 0.001, φc = 0.14), with respondents in the early perimenopause stage being less likely to have visited a HCP than both the post-menopause and medically induced menopause groups. In addition, there were significant differences in the type of HCP seen for menopausal symptoms between the groups, specifically with regard to seeing a NHS gynaecologist (χ²(3, N = 709) = 30.90, p < 0.001, φc = 0.21) and a private HCP (χ²(3, N = 709) = 9.48, p = 0.024, φc = 0.12). The medically induced menopause group was more likely to have seen a NHS gynaecologist relative to all other groups, and to have seen a private HCP in comparison to those in the early perimenopause stage. For those who had visited a HCP for their menopausal symptoms, there were significant group differences in the use of oral and topical medication (oral medication: χ²(3, N = 709) = 12.60, p = 0.006, φc = 0.13; topical medication (e.g., vaginal oestrogen creams): χ²(3, N = 709) = 15.20, p = 0.002, φc = 0.15). Respondents in the early perimenopause stage were less likely to have used oral medication relative to all other groups, as well as topical medication (e.g., vaginal oestrogen creams) in comparison to the medically induced menopause group. There was also a significant group difference in the proportion of respondents who had received no treatment or support for their menopausal symptoms (χ²(3, N = 709) = 9.88, p = 0.020, φc = 0.12), with respondents in the early perimenopause stage being more likely to have had no treatment or support than the post-menopause group. Finally, there was a significant group difference in perceived overall quality of care for menopausal symptoms (H(3) = 11.44, p = 0.010), with the medically induced menopause group expressing significantly lower satisfaction relative to those in the late perimenopause stage (U = 3182, p < 0.001, r = 0.24). No other significant group differences were found.

Mental healthcare provision throughout the menopause

Respondents’ mental healthcare provision throughout the menopause can be found in Fig. 3 and Supplementary Table 1C (Supplementary Materials). Overall, the majority of respondents (86.76%, n = 826) expressed that their menopausal symptoms had negatively affected their mental health (Fig. 3A), with 61.26% (n = 506) of these stating that they had visited a HCP to discuss their mental health symptoms since the onset of the menopause transition. Only 28.49% (n = 202) reported that they felt the HCPs involved in the management and treatment of their menopausal symptoms were aware of the (peri)menopause impact on their mental health, and only 24.40% (n = 173) were provided with mental health information by their HCP (Fig. 3B). In addition, 33.99% (n = 241) respondents expressed that they had been asked about their mental health by a HCP involved in the management and treatment of their menopausal symptoms (Figs. 3C), and 7.85% (n = 58) had been asked to complete a mental health assessment (Fig. 3D). Overall, in terms of perceived quality of care for mental health symptoms, 36.36% (n = 184) of respondents expressed that they felt their mental health symptoms related to the menopause were not taken at all seriously by their HCP, while 63.64% (n = 322) stated that their mental health symptoms related to the menopause were taken at least slightly seriously by their HCP (Fig. 3E). 43.70% (n = 416) of respondents expressed that the best method to provide information on mental health symptoms related to the menopause would be at first contact with a HCP for any menopausal symptom (Fig. 3F). This was closely followed by providing information via text or post to anyone approaching the average age for the menopause transition (42.86%, n = 408) (Fig. 3F).

A Menopause symptoms affected MH, B Provided with MH information by HCP involved in menopausal care, C Asked about MH by HCP involved in menopausal care, D Asked to complete a MH questionnaire by HCP involved in menopausal care, E MH symptoms related to the menopause taken seriously, and F Best method to provide information on MH symptoms related to the menopause. Key. HCP healthcare professional, MH mental health. a Includes those who reported that their menopausal symptoms have negatively affected their mental health (n = 826); b includes those who have visited a HCP for their menopausal symptoms OR their mental health symptoms related to the menopause (n = 739).

For a summary of between-group comparisons (i.e., early perimenopause stage, late perimenopause stage, post-menopause, medically induced menopause) on mental healthcare provision throughout the menopause see Supplementary Table 1C (Supplementary Materials). No significant group differences were found.

Experiences regarding poor or very poor menopausal care: thematic analysis

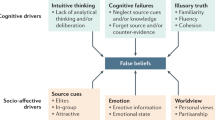

Of the 251 (35.40%) respondents who reported having received poor or very poor quality of menopausal care by their HCP, 170 provided (optional) open-ended response data regarding whether they had received any comments about the menopause from a HCP that had seemed unusual or inappropriate and how that made them feel. Of these, 159 open-ended responses were included in a thematic analysis as two respondents only responded ‘no’ and nine responses could not be categorised and were therefore excluded. Thematic analysis revealed six themes: consequences of poor care experiences, HCP was dismissive or negative, poor perception of treatment management, lack of symptom information and misattribution, HCP knowledge, and self-advocacy (see Fig. 4 for a summary of the sub-themes and themes generated).

Consequences of poor care experiences was a key theme generated, with respondents expressing feeling unsupported by their HCP, stating that they “felt dismissed” [late perimenopause stage, age 50] and as if they were “just another person and not listened to or understood” [early perimenopause stage, age 51]. Poor or very poor experiences of menopausal care resulted in some respondents feeling negative emotions, including feeling “hopeless” [post-menopause, age 56] and “unimportant, disregarded” [medically induced menopause, age 41]. Respondents also expressed that the poor quality of their menopausal care had resulted in years lost, such that “after 7 years of being given the wrong treatment, [they were] told there was nothing more they could do” [post-menopause, age 55] and that they were told they “had to suck it up… for 6 years [by] multiple gps” [medically induced menopause, age 41]. In turn, poor care experiences resulted in respondents feeling discouraged from further formal help-seeking, including feeling “entirely put off seeking any further help” [post-menopause, age 55] and that “there’s no point going back to ask for HRT [hormone replacement therapy]” [early perimenopause stage, age 43]. Furthermore, respondents expressed being made to feel as if they were a burden by their HCP when seeking help, for example “I felt like I had wasted his [HCP] time and just to ‘get on with it’” [post-menopause, age 56], and “…was made to feel like I was being unreasonable in raising it with the GP, and that I was wasting her time” [post-menopause, age 55].

The second theme identified regarded HCPs being perceived as dismissive or negative. Respondents expressed that their menopausal symptoms had been dismissed due to their age, for instance one respondent was told they were “too young for perimenopause at 41” [late perimenopause stage, age 47] and another that they “too young to be going through menopause, despite only having one ovary and with both [their] mum and sister going through menopause in their early 40’s” [early perimenopause stage, age 42]. Some respondents felt their menopause symptoms had been dismissed as being a natural aspect of aging, including being told that the “menopause is a natural process that the majority of women go through with no need for support” [post-menopause, age 55] and that there are “women in 3rd world countries without medication so [they] should be able to” deal with it too [early perimenopause stage, age 44]. Others expressed that their symptoms had been ignored following a hormonal blood test result, for instance: “I have been told that because the blood test result I received was normal it was unlikely that my symptoms related to the menopause” [early perimenopause stage, age 53] while another was told that their “hormone levels were normal and [their] symptoms would probably go away” [late perimenopause stage, age 47]. Some respondents’ mental health symptoms related to the menopause were dismissed, with one expressing that “no mental health support was recommended even though [their] symptoms included depression and anxiety” [early perimenopause stage, age 47] and another respondent stating that their HCP had told them that “the menopause is not a reason to be off work… [despite] having a week to 10 days with full blown depression like symptoms” [medically induced menopause, age 54]. Similarly, respondents reported that symptoms related to poor sexual functioning or reduced libido had been ignored or dismissed, with one respondent expressing the following: “I told GP I had lost my sex drive which was effecting [sic] my relationship. They ignored what I’d said and offered me antidepressants and advised CBT” [early perimenopause stage, age 51]. Others expressed that the impact of the menopause on their quality of life had been dismissed, resulting in “…the effect on [their] life [being] diminished at best and ignored at worst” [early perimenopause stage, age 41]. Medical gaslighting was also identified, such that HCPs made patients feel as if they were “a neurotic mess” [post-menopause, age 57] or that they must be “imagining the symptoms” [medically induced menopause, age 41]. In addition, respondents stated that they had received a rude or inappropriate comment, such as “all women in their 40s are miserable” [early perimenopause stage, age 41] and that they “needed to ‘get a life’ and forget [they were] ill” [post-menopause, age 58].

The third major theme concerned respondents’ perceptions of treatment management. One respondent expressed that “there is a tendency to jump very quickly to antidepressants rather than HRT” [post-menopause, age 46]. Another respondent stated that they were “offered antidepressants repeatedly until [they] thought [they were] actually depressed” [early perimenopause stage, age 51]. Respondents also felt that their treatment had been poorly managed by their HCP. This included a lack of monitoring of treatment efficacy and response, for instance a respondent said: “she [HCP] started me on hrt then left me a year till she reviewed my regime then changed my current regime and said I’d have another review in about a year again, it’s not acceptable to be left struggling like this with no funds to go private” [early perimenopause stage, age 49]. Respondents also expressed feelings of not being involved in decision-making regarding their treatment, such that when one respondent mentioned side effects, they were not “offered alternatives, just stopping” [late perimenopause stage, age 53]. Another respondent stated that their “1st doctor was male and wouldn’t prescribe HRT as his wife had gone thru [sic] menopause naturally and he recommended the same even though [they] asked for HRT to be prescribed he still refused” [medically induced menopause, age 45]. Respondents expressed having received no signposting to additional information or sources of help, for instance one respondent expressed that they were “unable to go on HRT due to many reasons and wasn’t given any advice or help about how to source any other help” [post-menopause, age 53], while another was given “no advice… from GP when [they were] first told [they] were probably perimenopausal” and that they “would’ve liked some information or to be directed where to get reliable information” [early perimenopause stage, age 54]. Finally, respondents with medically induced menopause expressed having received no treatment: “no proper review or discussion about options to manage menopausal symptoms post hysterectomy” [medically induced menopause, age 55] while another was “told by GP its [sic] to be expected that [their] symptoms were due to surgery” but received “no treatment despite symptoms for 2 years” [medically induced menopause, age 57].

Another major theme identified regarded the lack of information regarding the symptomatology of the menopause and issues surrounding misattribution of menopausal symptoms to other health conditions or lifestyle factors. Respondents expressed that their HCP had not provided them with any information on the menopause or menopause transition, including treatment options or directing them to reliable sources of information. In this regard, one patient stated that they were “mystified why menopause was never mentioned or suggested” when they went to see a HCP about their “low mood, hot flushes, [and] fatigue” [late perimenopause stage, age 44], while another stated that there had been “no mention that what [they were] experiencing was perimenopause” [late perimenopause stage, age 51]. In addition, some respondents stated that their menopausal symptoms had been attributed to other health conditions such that “it’s probably just long covid” [early perimenopause stage, age 38] or “just depression and anxiety” [late perimenopause stage, age 46]. Similarly, respondents also commented on the fact that their menopausal symptoms had been trivialised as being due to their weight or lifestyle factors, such as being told “to loose [sic] weight and [they] would feel better” [post-menopause, age 54] or that their symptoms were “due to stress” [early perimenopause stage, age 44].

Respondents also commented on HCPs’ knowledge, noting that their HCP was uneducated about the menopause. For instance, one respondent expressed that their “GP was unable to answer [their] questions about effects of hormones on [their] symptoms as she did not have enough knowledge herself” [early perimenopause stage, age 52]. Another expressed that “the doctor did not have a clue, kept saying erm and I could tell he was reading off the internet” [late perimenopause stage, age 52]. Related to this, respondents also provided comments that they had received about the menopause and its treatment that were incorrect, such that because they “didn’t have hot flushes, HRT wouldn’t help” [late perimenopause stage, age 61] and that “there’s no evidence that depression and anxiety are symptoms of menopause” [medically induced menopause, age 56].

The final theme regarded self-advocacy. Some respondents expressed that they felt that they had to take responsibility for the identification of the menopause symptoms and management options and share this with their HCP, with one respondent stating “after my own research I went to GP and told them it was perimenopause and I was prescribed HRT which made a big difference suggesting I was correct” [early perimenopause stage, age 49]. Another respondent stated that they “had to print out information from the NHS website to show [their] GP” [post-menopause, age 62]. Similarly, some respondents commented on the fact that they had to insist on being prescribed HRT medication, such that one respondent “suffered for nearly 10 years before demanding HRT from [their] GP” [late perimenopause stage, age 54]. Another respondent expressed that “it took 3 years of [them] insisting and for [their] periods to stop completely for a year for the gp to prescribe hrt” [late perimenopause stage, age 46].

Discussion

Healthcare provision throughout the menopause

The vast majority of women in the current study had disclosed their menopausal symptoms to a HCP, primarily relying on NHS GPs for assistance. Notably, help-seeking behavior varied between women with medically induced menopause and those experiencing natural menopause, with the former group being more likely to have discussed their symptoms with NHS gynaecologists or private HCPs. The findings also revealed that the majority of women who sought HCP advice had awareness prior to their appointment with a HCP that the menopause could be the underlying cause, indicating a reasonable level of knowledge and understanding regarding the hormonal changes during this life phase.

It has been previously suggested that women with higher education levels tend to have greater menopause awareness29. Given that a significant proportion of the women in this study were highly educated, it is possible that their awareness levels may not be representative of the general population in the UK, which is likely to have lower menopause awareness overall. Importantly, menopause awareness plays a critical role in shaping women’s perception of symptom severity and their overall quality of life30, with research highlighting that a better understanding and awareness of the menopause and its transition allow women to feel more empowered to make better healthcare decisions during this phase of life31,32.

When it came to treatment or support options, the most commonly reported approaches were oral medication, vaginal oestrogen creams, and lifestyle changes. Notably, women in the early perimenopause stage were less likely to receive any treatment or support compared to women in the post-menopause group. This could be due to a lack of awareness or understanding among HCPs regarding the potential impact of early perimenopause symptoms and the benefits of early intervention. Indeed, there exists evidence that the early perimenopause stage may hold particular significance when it comes to the success of hormone-based treatments for menopausal symptoms33,34. Furthermore, addressing menopausal symptoms during the early perimenopause stage can have broader health implications, such as improved cardiovascular health and bone density35,36,37,38, as well as reducing the risk of Alzheimer’s disease39,40.

Mental healthcare provision throughout the menopause

The majority of women experienced negative effects on their mental health due to menopausal symptoms. Around two-thirds of these women sought help from a HCP specifically for their mental health symptoms related to menopause. However, less than one-third of the women believed that the HCPs involved in their menopausal care had sufficient knowledge about the impact of the menopause on mental health. Additionally, only a quarter of women received information about mental health symptoms related to menopause, and just over a third were asked about their mental health by the HCPs involved in their menopausal care.

Critically, only around 8% of women were asked to complete a mental health assessment as part of their menopausal care, and over a third of women felt that their mental health symptoms related to menopause were not taken seriously by their HCPs. Overall, these findings suggest that mental health symptoms during the menopause are frequently overlooked by HCPs, in spite of their prevalence41,42, and that mental health screening is not consistently integrated into menopausal healthcare. Given that the menopause represents a period of increased vulnerability for mental health issues16, this indicates a missed opportunity to identify and address potential mental health concerns that may arise during this phase of life.

Overall quality of menopausal care provision

Overall, women’s satisfaction with menopausal care was mixed. Approximately one-third of women felt that they had received good or very good care. However, a similar proportion expressed dissatisfaction, rating the care they had received as poor or very poor. It is worth noting that women who experienced medically induced menopause reported lower satisfaction rates compared to those in the late perimenopause stage, with the thematic analysis further revealing that menopause symptoms arising following surgery are often not acknowledged or dismissed. This indicates that there is room for improvement in meeting the needs and expectations of women undergoing menopausal transitions, particularly those with medically induced menopause.

The consequences of poor care experiences during the menopause were significant and multifaceted. Thematic analysis revealed that women felt unsupported, not taken seriously, or ignored by HCPs. These findings align with previous research highlighting the importance of available support for menopausal women, with a lack of support often leaving women feeling confused about their symptoms and unsure about how to manage them effectively43. The women in the study also blamed their doctors for showing little interest in the topic and felt let down by the lack of support provided43.

In our study, we observed comparable sentiments, with negative care experiences for the menopause frequently resulting in feelings of hopelessness, as well as feeling disregarded and unimportant. These experiences sometimes even deterred women from seeking further help altogether. Furthermore, HCPs were frequently described as dismissive or negative, with medical gaslighting, where women felt their symptoms were being invalidated or made to feel like they were imagining them, also being mentioned. Some women reported that their menopausal symptoms were disregarded because they were considered too young or a natural part of aging. Notably, some researchers have challenged the idea that the menopause is characterised by a range of vasomotor, psychosocial, physical, and sexual symptoms, positing that only the former are specific to the menopause, while other symptoms are more strongly associated with socio-demographic variables6. While the symptoms of the menopause continue to be debated by clinicians and researchers, it is imperative that HCPs offer empathetic and supportive care during the menopause, ensuring that women feel heard, understood, and validated in their experiences.

Some women expressed dissatisfaction with the management of their treatment options during the menopause. They reported instances where HCPs made potentially inappropriate recommendations for antidepressants or psychiatric medication instead of hormone replacement therapy (HRT; also referred to as menopausal hormone therapy (MHT)). It is important to note, however, that antidepressants are a valid treatment option for mood-related menopause symptoms44. These findings may, therefore, be suggestive of a lack of women’s awareness regarding the available treatment approaches for the menopause, and potentially indicates a missed opportunity for HCPs to explain their decision-making in selecting antidepressants for the menopause. Indeed, these women felt that they were not adequately involved in the decision-making process and were not provided with sufficient information about their treatment options. This goes against the guidelines set forth by NICE in 201544, which emphasise the importance of HCPs offering evidence-based information on the benefits and risks of different treatment options, enabling women to make individualised decisions about their care.

A notable finding from this study was that a considerable number of women felt that their HCPs inaccurately attributed their menopausal symptoms to other health conditions or lifestyle factors. They reported instances where their symptoms were mistakenly linked to factors such as COVID-19, depression, anxiety, or weight. This highlights a concerning lack of knowledge or understanding about the menopause among HCPs. It is particularly alarming that some women received incorrect information about the menopause from their HCPs. In the UK, where primary care providers play a crucial role in managing menopause symptoms within the NHS, it is concerning that GPs often feel they lack adequate support to effectively advise and treat women experiencing menopausal symptoms45. Despite efforts to improve menopause training in medical schools, there is still a perceived need for further improvement in equipping GPs with the necessary knowledge and skills to provide comprehensive menopause care45.

Lastly, some women expressed a sense of needing to take personal responsibility for their own menopausal care. They reported having to conduct their own research and advocate for specific treatments, such as HRT. Similarly, previous research has shown that women often perceive their doctors as being too restrictive when it comes to prescribing hormone-based treatments, resulting in having to persuade their doctors to prescribe certain treatments and feeling fortunate if their doctor agreed43. Overall, the findings from the current study suggest a lack of proactive care within the healthcare system, where women perceive the need to take an active role in advocating for themselves to ensure they receive adequate care and treatment. Whilst self-advocacy and increased knowledge can be empowering and improve patient-HCP interactions, it should not be a requirement for the receipt of high-quality care.

Limitations

The study respondents had higher levels of education, a higher household income, and a higher proportion of white individuals compared to the general UK population. Therefore, the experiences and perspective captured in this study may not fully represent the wider UK population, as well as the experiences of ethnic minorities and disadvantaged populations in the UK, who may face additional challenges and negative experiences with menopausal care provision. Additionally, whilst social media recruitment and online survey delivery were chosen to maximise the sample size, this will have resulted in recruitment bias. For instance, it is likely that those who sought help for mental health symptoms related to their menopause will have been overrepresented, and, as such, the care experiences of the current sample may differ from the wider population of menopausal women in the UK. Moreover, individuals with negative experiences of care provision may have been more inclined to participate. These factors should be taken into consideration when interpreting the findings and extrapolating them to the wider UK population.

Conclusion

Taken together, the findings from this study highlight the need for immediate improvements in the delivery of healthcare services for women going through the menopause and menopause transition in the UK. The study brings to light the importance of recognising the unique care requirements of women who have undergone medically induced menopause, as their needs may differ from those who experience natural menopause. Furthermore, it is essential for HCPs to have an understanding of the physiological and psychological changes that occur during the menopause beyond the stereotypically associated symptoms, as well as the available treatment options, including the option of referring women to more specialised women’s health services.

The findings from the current study also emphasise the importance of delivering empathetic and supportive care to women during the menopause. Women’s experiences and symptoms during this phase of life can be challenging and disruptive, both physically and emotionally. It is crucial for HCPs to demonstrate empathy, actively listen to women’s concerns, and validate their experiences. Providing a supportive environment where women feel understood, heard, and respected is likely to improve their overall care experience and contribute to better outcomes.

Furthermore, involving women in decision-making processes regarding their menopausal care is paramount. Women should be encouraged to actively participate in their own care by being provided with comprehensive information about available treatment options, including their benefits, risks, and potential alternatives. By involving women in decision-making, HCPs can ensure that care plans are individualised, taking into account women’s preferences and goals. This collaborative approach can help foster a sense of ownership and empowerment, enabling women to make better informed choices about their health and wellbeing.

Methods

Participants

Participants were recruited between January 2023 and March 2023 via email, paid Facebook and Instagram advertisements, organic posts on the Cambridge Centre for Neuropsychiatric Research Facebook and Twitter pages, and Reddit. Recruitment messages were also disseminated by word-of-mouth and through relevant foundations and support groups. Inclusion criteria for the study were: (1) ≥ 18 years, (2) UK residence, (3) must be currently experiencing symptoms of the menopause or menopause transition (e.g., hot flushes, mood changes, night sweats, irregular or absent periods, decreased sex drive) and belong to one of the following groups: (i) early perimenopause stage: significant change in the length of menstrual bleed or the time between periods that is not due to pregnancy or breastfeeding, stress, or a medical condition, (ii) late perimenopause stage: no menstrual bleeding in 3–11 months not due to pregnancy or breastfeeding, stress, or a medical condition, (iii) post-menopause: no menstrual bleeding in 12 months not due to pregnancy or breastfeeding, stress, or a medical condition, or (iv) medically induced menopause: no menstrual bleeding due to hysterectomy with one or two ovaries retained or other medical procedure. Participants were also required to not be currently pregnant or breastfeeding and did not have to have been diagnosed with a mental health condition to take part in the study. There were no other inclusion criteria. Participants were invited to enter their email for the chance to win one of three £50 Highstreet vouchers.

Materials and procedure

Given the uniqueness of the UK’s healthcare system and the fact that, to our knowledge, there is no validated measure that can capture the nuances of healthcare experiences and perceptions specific to the menopause, the creation of an anonymous online survey was deemed appropriate for the current study. The survey was created using Qualtrics XM® in order to explore the current state of care provision offered via healthcare services in the UK throughout the menopause and menopause transition. The survey questions and accompanying study materials were designed in consultation with an experienced psychiatrist (SB).

The survey could be completed in 15-20 minutes and comprised eight sections: (1) participant information sheet detailing the rational for the study, (2) electronic consent form, (3) socio-demographic information, (4) healthcare provision throughout the menopause, (5) mental health symptoms and care provision throughout the menopause, (6) menopause-specific quality of life symptoms, (7) experiences and interest in using digital technology for mental health symptoms related to the menopause, and (8) debrief. For the purpose of the current study, data regarding mental health symptoms and data from sections six and seven were not included. The survey was adaptive in nature, such that only relevant questions were asked based on previous responses. It also included an optional open-ended question regarding whether respondents had received any comments about the menopause from a HCP that had seemed unusual or inappropriate and how that made them feel.

Data analytic strategy

Quantitative data were processed and analysed in SPSS version 28.0.1.1. Figures were created using Excel version 2206 and PowerPoint version 2206 (Microsoft Office 365). Group differences (i.e., early perimenopause stage, late perimenopause stage, post-menopause, medically induced menopause) in continuous variables were explored using one-factor ANOVAs, with effect sizes reported as eta-squared (η2; small = 0.01, medium = 0.06, large = 0.1446). Where appropriate, pairwise comparisons subject to the Bonferroni-correction method for multiple comparisons were conducted. Group differences in ordinal variables were explored using Kruskal-Wallis H tests, with posthoc Mann-Whitney U tests subject to the Bonferroni-correction method for multiple comparisons conducted where appropriate. Effect sizes are reported as r (small = 0.10, medium = 0.30, large = 0.5046). Comparisons on binary variables were conducted using Chi-Square tests (χ²) or Fisher’s Exact Test (FET) for low frequency data (i.e., values below five). Effect sizes are reported as Cramer’s V (φc; small = 0.10, medium = 0.30, large = 0.5046).

Qualitative data were analysed following the recommended six stages of thematic analysis47. These data comprised (optional) open-ended responses regarding comments about the menopause from a HCP that had seemed unusual or inappropriate and how that made them feel. Given that this question aimed to gather in-depth views of negative experiences regarding menopausal care provision, only responses from those who had reported having received poor or very poor quality of menopausal care by their HCP were included in the analysis. The following steps were conducted: (1) The second author (EF) became familiar with the data by reading and rereading the open-ended responses and noting down ideas. (2) The second author (EF) generated initial codes, and a codebook was produced, including a brief descriptions for each code. (3) The first two authors (NAM-K, EF) performed a blinded allocation of codes to each of the open-ended responses using the codebook. (4) Following this, any inconsistencies in coding were discussed until a consensus was reached. (5) The codes were then condensed into broad themes, with the first and second authors generating themes separately. (6) These were then discussed until a consensus was reached.

Data availability

The datasets used and analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author (SB) on reasonable request.

References

World Health Organization. World Health Report 2008: Women, Ageing and Health: A Framework for Action. 2008. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/43810/9789241563529_eng.pdf [Accessed May 4, 2023].

Hardy, C., Hunter, M. S. & Griffiths, A. Menopause and work: an overview of UK guidance. Occup. Med. 68, 580–586 (2018).

Hoga, L., Rodolpho, J., Gonçalves, B. & Quirino, B. Women’s experience of menopause: a systematic review of qualitative evidence. JBI Database System Rev. Implement Rep. 13, 250–337 (2015).

Delamater, L. & Santoro, N. Management of the Perimenopause. Clin. Obstet. Gynecol. 61, 419–432 (2018).

Avis, N. E. et al. Duration of menopausal vasomotor symptoms over the menopause transition. JAMA Intern. Med. 175, 531–539 (2015).

Weidner, K. et al. Menopausal syndrome limited to hot flushes and sweating a representative survey study. J. Psychosom. Obstet. Gynaecol. 38, 170–179 (2017).

Williams, R. E. et al. Healthcare seeking and treatment for menopausal symptoms in the United States. Maturitas 58, 348–358 (2007).

Karaçam, Z. & Seker, S. E. Factors associated with menopausal symptoms and their relationship with the quality of life among Turkish women. Maturitas 58, 75–82 (2007).

Avis, N. E. et al. Health-related quality of life in a multiethnic sample of middle-aged women: Study of Women’s Health Across the Nation (SWAN). Med. Care 41, 1262–1276 (2003).

Avis, N. E. et al. Change in health-related quality of life over the menopausal transition in a multiethnic cohort of middle-aged women: Study of Women’s Health Across the Nation. Menopause 16, 860–869 (2009).

Williams, R. E., Levine, K. B., Kalilani, L., Lewis, J. & Clark, R. V. Menopause-specific questionnaire assessment in US population-based study shows negative impact on health-related quality of life. Maturitas 62, 153–159 (2009).

Daly, E. et al. Measuring the impact of menopausal symptoms on quality of life. BMJ. 307, 836–840 (1993).

Bhattacharya, S. M. & Jha, A. A comparison of health-related quality of life (HRQOL) after natural and surgical menopause. Maturitas 66, 431–434 (2010).

Secoșan, C. et al. Surgically induced menopause-A practical review of literature. Medicina 55, 482 (2019).

Shuster, L. T., Gostout, B. S., Grossardt, B. R. & Rocca, W. A. Prophylactic oophorectomy in premenopausal women and long-term health. Menopause Int. 14, 111–116 (2008).

Soares, C. N. Depression and menopause: An update on current knowledge and clinical management for this critical window. Med. Clin. North Am. 103, 651–667 (2019).

Freeman, E. W. Associations of depression with the transition to menopause. Menopause 17, 823–827 (2010).

Bromberger, J. T. et al. Major depression during and after the menopausal transition: Study of Women’s Health Across the Nation (SWAN). Psychol. Med. 41, 1879–1888 (2011).

Gibbs, Z., Lee, S. & Kulkarni, J. The unique symptom profile of perimenopausal depression. Clin. Psychologist 19, 76–84 (2015).

Chedraui, P., Pérez-López, F. R., Morales, B. & Hidalgo, L. Depressive symptoms in climacteric women are related to menopausal symptom intensity and partner factors. Climacteric 12, 395–403 (2009).

Melby, M. K., Anderson, D., Sievert, L. L. & Obermeyer, C. M. Methods used in cross-cultural comparisons of vasomotor symptoms and their determinants. Maturitas 70, 110–119 (2011).

Reed, S. D. et al. Depressive symptoms and menopausal burden in the midlife. Maturitas 62, 306–310 (2009).

Chedraui, P. et al. Severe menopausal symptoms in middle-aged women are associated to female and male factors. Arch. Gynecol. Obstet. 281, 879–885 (2010).

Gracia, C. R. & Freeman, E. W. Onset of the menopause transition: the earliest signs and symptoms. Obstet. Gynecol. Clin. North Am. 45, 585–597 (2018).

Weiss, S. J. et al. Anxiety and physical health problems increase the odds of women having more severe symptoms of depression. Arch Womens Ment. Health 19, 491–499 (2016).

Vivian-Taylor, J. & Hickey, M. Menopause and depression: is there a link? Maturitas 79, 142–146 (2014).

Stanzel, K. A., Hammarberg, K. & Fisher, J. Experiences of menopause, self-management strategies for menopausal symptoms and perceptions of health care among immigrant women: a systematic review. Climacteric 21, 101–110 (2018).

Newson, L. & Connolly, A. Survey demonstrates suboptimal menopause care in UK despite NICE guidelines. Maturitas 124, 136 (2019).

İkiışık, H. et al. Awareness of menopause and strategies to cope with menopausal symptoms of the women aged between 40 and 65 who consulted to a tertiary care hospital. ESTUDAM Public Health J. 5, 10–21 (2020).

Whiteley, J., DiBonaventura, M. D., Wagner, J. S., Alvir, J. & Shah, S. The impact of menopausal symptoms on quality of life, productivity, and economic outcomes. J. Womens Health 22, 983–990 (2013).

Woods, N. F. & Mitchell, E. S. The Seattle Midlife Women’s Health Study: a longitudinal prospective study of women during the menopausal transition and early postmenopause. Womens Midlife Health 2, 6 (2016).

Yazdkhasti, M., Simbar, M. & Abdi, F. Empowerment and coping strategies in menopause women: a review. Iran Red. Crescent Med. J. 17, e18944 (2015).

Soares, C. N. & Maki, P. M. Menopausal transition, mood, and cognition: an integrated view to close the gaps. Menopause 17, 812–814 (2010).

Fait, T. Menopause hormone therapy: latest developments and clinical practice. Drugs Context 8, 212551 (2019).

Manson, J. E. et al. Menopausal hormone therapy and health outcomes during the intervention and extended poststopping phases of the Women’s Health Initiative randomized trials. JAMA. 310, 1353–1368 (2013).

Gambacciani, M. & Levancini, M. Hormone replacement therapy and the prevention of postmenopausal osteoporosis. Prz Menopauzalny 13, 213–220 (2014).

Sanghvi, M. M. et al. The impact of menopausal hormone therapy (MHT) on cardiac structure and function: Insights from the UK Biobank imaging enhancement study. PLoS One 13, e0194015 (2018).

Nelson, H. D., Humphrey, L. L., Nygren, P., Teutsch, S. M. & Allan, J. D. Postmenopausal hormone replacement therapy: scientific review. JAMA 288, 872–881 (2002).

Mills, Z. B., Faull, R. L. M. & Kwakowsky, A. Is hormone replacement therapy a risk factor or a therapeutic option for Alzheimer’s disease? Int. J. Mol. Sci. 24, 3205 (2023).

Saleh, R. N. M., Hornberger, M., Ritchie, C. W. & Minihane, A. M. Hormone replacement therapy is associated with improved cognition and larger brain volumes in at-risk APOE4 women: results from the European Prevention of Alzheimer’s Disease (EPAD) cohort. Alzheimers Res. Ther. 15, 10 (2023).

Glynne, S., Reisel, D., Lewis, R. & Newson, L. Prevalence and nature of negative mood symptoms in perimenopause and menopause. Maturitas 173, 93 (2023).

Wang, X., Zhao, G., Di, J., Wang, L. & Zhang, X. Prevalence and risk factors for depressive and anxiety symptoms in middle-aged Chinese women: a community-based cross-sectional study. BMC Womens Health 22, 319 (2022).

Duffy, O., Iversen, L. & Hannaford, P. C. The menopause ‘It’s somewhere between a taboo and a joke’. A focus group study. Climacteric 14, 497–505 (2011).

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Menopause: diagnosis and management. Nice diagnostic guidance NG23. 2015. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng23 [accessed June 1, 2023].

Dintakurti, N., Kalyanasundaram, S., Jha, P. & Talaulikar, V. An online survey and interview of GPs in the UK for assessing their satisfaction regarding the medical training curriculum and NICE guidelines for the management of menopause. Post Reprod. Health 28, 137–141 (2022).

Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences (2nd Edition). New York: Academic Press; 1–978. (1988).

Braun, V. & Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 3, 77–101 (2006).

Acknowledgements

We are most grateful to all the survey respondents for their participation. This study was funded by Stanley Medical Research Institute (grant number 07R-1888). The funder played no role in study design, data collection, analysis and interpretation of data, or the writing of this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

N.A.M.-K., E.F., B.S., and S.B. conceived the study focus and materials. E.F. coordinated and conducted participant recruitment. Data analysis was performed by N.A.M.-K.. N.A.M.-K. and E.F. prepared the manuscript with revisions from B.S. and S.B. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

Author S.B. holds shares in Psyomics Ltd but declares no non-financial competing interests. Author E.F. is a paid consultant for Psyomics Ltd but declares no non-financial competing interests. Authors N.A.M.-K. and B.S. declare no financial or non-financial competing interests.

Ethical approval and informed consent

The study was approved by the University of Cambridge Human Biology Research Ethics Committee (approval number PRE.2022.110). All participants provided informed consent electronically to participate in the study.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Martin-Key, N.A., Funnell, E.L., Spadaro, B. et al. Perceptions of healthcare provision throughout the menopause in the UK: a mixed-methods study. npj Womens Health 1, 2 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s44294-023-00002-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s44294-023-00002-y