Abstract

Freshwater is closely interconnected with multiple sustainable development goals (SDGs). Virtual water transfer associated with agricultural trade may help to mitigate water scarcity (SDG6). However, the resulting impacts on water scarcity distribution among income groups (SDG1) and subsequent effects on water use inequality and inequity (SDG10) remain largely unclear. Here we develop an integrated framework to reveal the asymmetric impacts of international agricultural trade on water use scarcity, inequality and inequity between and within developing and developed countries. We find that although agricultural trade generally relieves water scarcity globally, it disproportionately benefits the rich and widens both the water scarcity and inequity gap between the poor and the rich. Notably, in developing countries, the population (35%) suffering from both increased water scarcity and inequity are the poorest group (per capita income is 16% lower than average), whereas the relatively poor (13% population) in developed countries often simultaneously benefit from decreased water scarcity and reduced inequity synergies. Our results thereby highlight striking asymmetric and generally more favourable trade-induced water impacts for developed countries, urging future water and trade policies striving for a better balance across multiple critical SDGs and achieving sustainable development for all.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 digital issues and online access to articles

$99.00 per year

only $8.25 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

Data used to perform this work can be found in the Supplementary Information. Numerical results for Figs. 1–5 are provided with this paper as Source Data, any further data that support the main findings of this study are available from the corresponding authors upon request. Source data are provided with this paper.

Code availability

Computer code or algorithm used to generate results that are reported in the paper and central to the main claims are available from the corresponding authors upon request.

References

Wang, M. R. et al. Accounting for interactions between sustainable development goals is essential for water pollution control in China. Nat. Commun. 13, 730 (2022).

Ma, T. et al. Pollution exacerbates China’s water scarcity and its regional inequality. Nat. Commun. 11, 650 (2020).

Sun, S. et al. Unraveling the effect of inter-basin water transfer on reducing water scarcity and its inequality in China. Water Res. 194, 116931 (2021).

Fischer, C., Aubron, C., Trouve, A., Sekhar, M. & Ruiz, L. Groundwater irrigation reduces overall poverty but increases socioeconomic vulnerability in a semiarid region of southern India. Sci. Rep. 12, 8850 (2022).

Rosa, L., Chiarelli, D. D., Rulli, M. C., Dell’Angelo, J. & D’Odorico, P. Global agricultural economic water scarcity. Sci. Adv. 6, eaaz6031 (2020).

Bleischwitz, R. et al. Resource nexus perspectives towards the United Nations sustainable development goals. Nat. Sustain. 1, 737–743 (2018).

The Sustainable Development Goals Report (United Nations, 2022); https://www.un.org/development/desa/dspd/2022/07/sdgs-report/

Wiedmann, T. & Lenzen, M. Environmental and social footprints of international trade. Nat. Geosci. 11, 314–321 (2018).

Liu, X. et al. Can virtual water trade save water resources? Water Res. 163, 114848 (2019).

Deng, J. et al. The impact of water scarcity on Chinese inter-provincial virtual water trade. Sustain. Prod. Consump. 28, 1699–1707 (2021).

D’Odorico, P. et al. Global virtual water trade and the hydrological cycle: patterns, drivers, and socio-environmental impacts. Environ. Res. Lett. 14, 053001 (2019).

Chapagain, A. K., Hoekstra, A. Y. & Savenije, H. H. G. Water saving through international trade of agricultural products. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 10, 455–468 (2006).

Hoekstra, A. Y. & Hung, P. Q. Globalisation of water resources: international virtual water flows in relation to crop trade. Glob. Environ. Change 15, 45–56 (2005).

Liu, W. F. et al. Savings and losses of global water resources in food-related virtual water trade. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev.: Water 6, e1320 (2019).

Konar, M., Dalin, C., Hanasaki, N., Rinaldo, A. & Rodriguez-Iturbe, I. Temporal dynamics of blue and green virtual water trade networks. Water Resour. Res. 48, W07509 (2012).

Mekonnen, M. M. & Hoekstra, A. Y. A global and high-resolution assessment of the green, blue and grey water footprint of wheat. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 14, 1259–1276 (2010).

Mekonnen, M. M. & Hoekstra, A. Y. The green, blue and grey water footprint of crops and derived crop products. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 15, 1577–1600 (2011).

O’Bannon, C., Carr, J., Seekell, D. A. & D’Odorico, P. Globalization of agricultural pollution due to international trade. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 18, 503–510 (2014).

Pfister, S., Bayer, P., Koehler, A. & Hellweg, S. Environmental impacts of water use in global crop production: hotspots and trade-offs with land use. Environ. Sci. Technol. 45, 5761–5768 (2011).

Lenzen, M. et al. International trade of scarce water. Ecol. Econ. 94, 78–85 (2013).

Zhao, X. et al. Physical and virtual water transfers for regional water stress alleviation in China. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 112, 1031–1035 (2015).

Dalin, C., Wada, Y., Kastner, T. & Puma, M. J. Groundwater depletion embedded in international food trade. Nature 543, 700–704 (2017).

Qin, Y. et al. Snowmelt risk telecouplings for irrigated agriculture. Nat. Clim. Change 12, 1007–1015 (2022).

Seekell, D. A., D’Odorico, P. & Pace, M. L. Virtual water transfers unlikely to redress inequality in global water use. Environ. Res. Lett. 6, 024017 (2011).

Carr, J. A., Seekell, D. A. & D’Odorico, P. Inequality or injustice in water use for food? Environ. Res. Lett. 10, 024013 (2015).

Chen, W. M., Kang, J. N. & Han, M. S. Global environmental inequality: evidence from embodied land and virtual water trade. Sci. Total Environ. 783, 146992 (2021).

Li, H., Liu, X. M., Wang, S. & Wang, Z. H. Impacts of international trade on global inequality of energy and water use. J. Environ. Manage. 315, 115156 (2022).

Chancel, L. Global carbon inequality over 1990–2019. Nat. Sustain. 5, 931–938 (2022).

Diffenbaugh, N. S. & Burke, M. Global warming has increased global economic inequality. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 116, 9808–9813 (2019).

Tong, K. et al. Measuring social equity in urban energy use and interventions using fine-scale data. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 118, e2023554118 (2021).

Kummu, M., Taka, M. & Guillaume, J. H. A. Data descriptor: gridded global datasets for gross domestic product and human development index over 1990–2015. Sci. Data 5, 180004 (2018).

Kakwani, N., Wagstaff, A. & vanDoorslaer, E. Socioeconomic inequalities in health: measurement, computation, and statistical inference. J. Econom. 77, 87–103 (1997).

Wagstaff, A., Paci, P. & Vandoorslaer, E. On the measurement of inequalities in health. Social Sci. Med. 33, 545–557 (1991).

Zhang, X. et al. Socioeconomic inequities in health care utilization in China. Asia Pac. J. Public Health 27, 429–438 (2015).

Concentration Curves (World Bank, 2023); https://www.worldbank.org/content/dam/Worldbank/document/HDN/Health/HealthEquityCh7.pdf

The Concentration Index (World Bank, 2023); https://www.worldbank.org/content/dam/Worldbank/document/HDN/Health/HealthEquityCh8.pdf

D’Odorico, P., Carr, J. A., Davis, K. F., Dell’Angelo, J. & Seekell, D. A. Food inequality, injustice, and rights. Bioscience 69, 180–190 (2019).

Palomaki, G. E. & Neveux, L. M. Using multiples of the median to normalize serum protein measurements. Clin. Chem. Lab. Med. 39, 1137–1145 (2001).

Liu, H. Q., Wang, Y. H., Wang, L. L. & Hao, M. Predictive value of fFree beta-hCG multiple of the median for women with preeclampsia. Gynecol. Obstet. Invest. 81, 137–147 (2016).

Bestwick, J. P. et al. Thyroid stimulating hormone and free thyroxine in pregnancy: expressing concentrations as multiples of the median (MoMs). Clin. Chim. Acta 430, 33–37 (2014).

Xu, Z. C. et al. Impacts of international trade on global sustainable development. Nat. Sustain. 3, 964–971 (2020).

Metulini, R., Tamea, S., Laio, F. & Riccaboni, M. The water suitcase of migrants: assessing virtual water fluxes associated to human migration. PLoS ONE 11, e0153982 (2016).

Acey, C. et al. Cross-subsidies for improved sanitation in low income settlements: assessing the willingness to pay of water utility customers in Kenyan cities. World Dev. 115, 160–177 (2019).

Hung, M. F. & Chie, B. T. Residential water use: efficiency, affordability, and price elasticity. Water Resour. Manage. 27, 275–291 (2013).

Carrard, N. et al. Are piped water services reaching poor households? Empirical evidence from rural Viet Nam. Water Res. 153, 239–250 (2019).

Li, H. R. et al. Drip fertigation significantly increased crop yield, water productivity and nitrogen use efficiency with respect to traditional irrigation and fertilization practices: a meta-analysis in China. Agric. Water Manage. 244, 106534 (2021).

Liu, B. B. et al. Promoting potato as staple food can reduce the carbon–land–water impacts of crops in China. Nat. Food 2, 570–577 (2021).

Chaudhary, B. & Kumar, V. Emerging technological frameworks for the sustainable agriculture and environmental management. Sustain. Horiz. 3, 100026 (2022).

Fishman, R., Devineni, N. & Raman, S. Can improved agricultural water use efficiency save India’s groundwater? Environ. Res. Lett. 10, 084022 (2015).

Janssens, C. et al. Global hunger and climate change adaptation through international trade. Nat. Clim. Change 10, 829–835 (2020).

Lin, J. T. et al. Carbon and health implications of trade restrictions. Nat. Commun. 10, 4947 (2019).

Mishra, R. K. & Karthik, M. Understanding the US–China trade war: causes, consequences and economic impact. Glob. Trade Cust. J. 15, 580–591 (2020).

Disdier, A. C., Fontagne, L. & Mimouni, M. The impact of regulations on agricultural trade: evidence from the SPS and TBT agreements. Am. J. Agr. Econ. 90, 336–350 (2008).

Kharrazi, A. et al. Examining the ecology of commodity trade networks using an ecological information-based approach: toward strategic assessment of resilience. J. Ind. Ecol. 19, 805–813 (2015).

Hicks, C. C. et al. Rights and representation support justice across aquatic food systems. Nat. Food 3, 851–861 (2022).

Moran, D. D., Lenzen, M., Kanemoto, K. & Geschke, A. Does ecologically unequal exchange occur? Ecol. Econ. 89, 177–186 (2013).

Debaere, P. The global economics of water: is water a source of comparative advantage? Am. Econ. J. Appl. Econ. 6, 32–48 (2014).

Tobin, James On limiting the domain of inequality. J. Law Econ. 13, 263–277 (1970).

Hoekstra, A. Y. & Mekonnen, M. M. The water footprint of humanity. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 109, 3232–3237 (2012).

Mekonnen, M. M. & Hoekstra, A. Y. Blue water footprint linked to national consumption and international trade is unsustainable. Nat. Food 1, 792–800 (2020).

Siebert, S. & Doll, P. Quantifying blue and green virtual water contents in global crop production as well as potential production losses without irrigation. J. Hydrol. 384, 198–217 (2010).

Siebert, S. et al. Development and validation of the global map of irrigation areas. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 9, 535–547 (2005).

Allen, R. G., Pereira, L. S., Raes, D. & Smith, M. Crop Evapotranspiration—Guidelines for Computing Crop Water Requirements Paper 56 (FAO Irrigation and Drainage, 1998).

Portmann, F. T., Siebert, S. & Doll, P. MIRCA2000—global monthly irrigated and rainfed crop areas around the year 2000: a new high-resolution data set for agricultural and hydrological modeling. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycle 24, GB1011 (2010).

Qin, Y. et al. Agricultural risks from changing snowmelt. Nat. Clim. Change 10, 459–465 (2020).

Qin, Y. et al. Flexibility and intensity of global water use. Nat. Sustain. 2, 515–523 (2019).

Food and Agriculture Data (FAO, 2022); https://www.fao.org/faostat/en/#data

ERA5 Monthly Averaged Data on Single Levels from 1940 to Present (European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts, 2023); https://cds.climate.copernicus.eu/cdsapp#!/dataset/reanalysis-era5-single-levels-monthly-means?tab=overview

Kastner, T., Kastner, M. & Nonhebel, S. Tracing distant environmental impacts of agricultural products from a consumer perspective. Ecol. Econ. 70, 1032–1040 (2011).

Water Availability Indices—A Literature Review (Argonne National Laboratory, 2023); https://publications.anl.gov/anlpubs/2017/03/134309.pdf

Hanasaki, N. et al. A global water scarcity assessment under shared socio-economic pathways—part 1: water use. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 17, 2375–2391 (2013).

Oki, T. & Kanae, S. Global hydrological cycles and world water resources. Science 313, 1068–1072 (2006).

Hoekstra, A. Y., Mekonnen, M. M., Chapagain, A. K., Mathews, R. E. & Richter, B. D. Global monthly water scarcity: blue water footprints versus blue water availability. PLoS ONE 7, e32688 (2012).

Goldewijk, K. K., Beusen, A. & Janssen, P. Long-term dynamic modeling of global population and built-up area in a spatially explicit way: HYDE 3.1. Holocene 20, 565–573 (2010).

IMF Country Information (IMF, 2023); https://www.imf.org/en/Countries

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant 42277482 to Y.Q., grant 42361144876 to F.Z., Q.Z., X.W. and Y.Q. and grant 42171096 to X.W.). L.Y. acknowledges support from National Key R&D Plan Intergovernmental International Science and Technology Innovation Cooperation Key Special Project of China (2022YFE0138300) and Yunnan Key R&D Plan Program (202302A0370015). W.G. acknowledges support from Peking University-BHP Carbon and Climate Wei-Ming PhD Scholars (WM202306). C.H. acknowledges support from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (42277087). F.W. acknowledges support from the Key Project of the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant number 52130804). S.S. received funding by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG, German Research Foundation)—SFB 1502-1-2022—projektnummer 450058266. M.K. acknowledges support from the European Research Council under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation program grant (SOS.aquaterra; grant agreement number 819202), the Research Council of Finland’s project TREFORM (grant 339834) and the Research Council of Finland’s Flagship Programme under project Digital Waters (359248). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish or preparation of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.Q. designed this study. W.G., C.H., S.S. and M.K. led the data analysis. Y.L., Q.Z., F.Z., X.W. and F.W. contributed to the discussion and interpretation of the results. W.G. and Y.Q. wrote the paper with input from all co-authors.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Water thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary, Notes, Tables 1–12 and Figs. 1–10.

Source data

Source Data Fig. 1

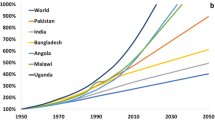

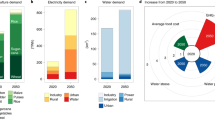

Asymmetric change of water scarcity embodied in international agricultural trade across developing/developed countries and populations.

Source Data Fig. 2

Asymmetric changes of water use inequality and inequity embodied in international agricultural trade across developing/developed countries and populations.

Source Data Fig. 3

Synergies and trade-offs between water scarcity, inequality and inequity embodied in international agricultural trade.

Source Data Fig. 4

Relative importance of crop-specific contribution to the change of water scarcity, inequality and inequity due to international agricultural trade for eight selected countries.

Source Data Fig. 5

Relative importance of trading-partner-specific contribution to the change of water scarcity, inequality and inequity due to international agricultural trade for eight selected countries.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Gu, W., Wang, F., Siebert, S. et al. The asymmetric impacts of international agricultural trade on water use scarcity, inequality and inequity. Nat Water 2, 324–336 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s44221-024-00224-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s44221-024-00224-7