Abstract

The relationship between mental health and social media has received significant research and policy attention. However, there is little population-representative data about who social media users are which limits understanding of confounding factors between mental health and social media. Here we profile users of Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, Snapchat and YouTube from the Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children population cohort (N = 4083). We provide estimates of demographics and mental health and well-being outcomes by platform. We find that users of different platforms and frequencies are not homogeneous. User groups differ primarily by sex and YouTube users are the most likely to have poorer mental health outcomes. Instagram and Snapchat users tend to have higher well-being than the other social media sites considered. Relationships between use-frequency and well-being differ depending on the specific well-being construct measured. The reproducibility of future research may be improved by stratifying by sex and being specific about the well-being constructs used.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The trails of data left online by our digital footprints are increasingly being used to measure and understand our health and well-being. Data sourced from social media platforms has been of particular interest given their potential to be used as a form of ‘natural’ observational data about anything from our voting intentions to symptoms of disease. There is not a single, widely agreed definition of the term ‘social media’1, but for the purposes of this study we understand it to be a broad category of internet-based platforms that allow for the exchange of user-generated content by ‘users’ of that platform2. Both the huge volumes of data available on such platforms, and their increasing uptake across the population3 have led to two main fields of interest in the intersections of social media and mental health. These are the prediction of mental health and well-being from our online data4 and, somewhat reciprocally, the influence of social media on our mental health, particularly in the case of children and young people5,6. These fields both ask fundamental questions about the mental health and well-being of social media users, to either understand the ways our mental health influences our social media behaviour, or how our social media behaviours influence our mental health.

Across both contexts a wide range of psychological outcomes have been studied, including predicting suicide at a population-level7 and individually8, mapping the influences of social media platforms on disordered eating9 and self-harm10, understanding the impacts of cyberbullying through social media platforms11,12, and even ethnographic research into online support networks13. As highlighted in a recent review which considered research on the relationship between social media use and well-being in adolescents14, there has tended to be an inherent assumption that social media is the cause of harm when examining the effect of social media on our health. However, recent investigations such as those by Orben and Przybylski15,16 and Appel and colleagues17 illustrate that the role of social media in causing harm may be over-estimated. It seems likely that there is some reciprocal relationship between mental health and social media, that requires longitudinal research studies to begin to understand the complexity, coupled with large representative samples to explore the heterogeneity18,19. Further, there is increasing attention on the role of within-person effects that see impact change between contexts20,21, as well as individual differences22. Meanwhile, attention has also been drawn to the comparative lack of investigation into the potential benefits of social media, such as access to peer support and the ability to readily connect with friends and family, or into the psychological well-being of social media users as opposed to focusing on pathology. Similarly, most psychological prediction tasks using social media focus on predicting illness rather than wellness4,23.

Regardless of the direction of interest in the relationship between social media and psychological outcomes, researchers face common challenges, with one of the primary issues being a lack of high-quality information on the characteristics of the whole population of social media users24. Valuable demographic information on social media users in the United States is regularly produced by the Pew Research Centre25, but often researchers rely on algorithmic means to make predictions about the demographics of the groups they study online if they are not recruiting a participant sample whose demographics are known and can be recorded4,24,26. What we do know about social media users is that they are not homogeneous. The demographic features of populations using them vary across platforms and do not tend to be consistent with the characteristics of the general population25,26,27,28. This work on the demographic context has been important in understanding the samples that can be drawn from social media platforms, but there remains a lack of information about other characteristics of social media users that are relevant to study outcomes, including mental health and well-being. Consequently, attempts to compare user well-being and mental health between platforms may be unknowingly confounded by differences in the mental health profile of each individual platform. Mellon and Prosser28 investigated this form of selection bias with respect to differences in political opinion between Facebook and Twitter, and noted the potential for study outcomes to be biased when the outcome variable of interest is associated with the probability of being included in the sample29. This also has implications for our assessment of mental health and well-being classification algorithms30. For instance, if using Twitter data to classify depression in a random sample of users how many of these users should we expect to be depressed? Should we expect to find more depressed users on Facebook or Instagram? This bench-marking would allow the research community, who frequently face the challenge of establishing reliable ground truth in social media research, to contextualise the sensitivity and specificity of developed models4,24.

This study aimed to address the gap in the availability of high-quality descriptive data about social media users by describing social media use in a representative UK population cohort study, the Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children (ALSPAC)31. We aimed to profile the users of the social media platforms Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, Snapchat and YouTube by considering a range of mental health and well-being measures that are regularly studied, with the objective of better characterising social media users against variables of interest to researchers. These measures included disordered eating, self-harm, suicidal thoughts, and depression as well as positive well-being outcomes which are sometimes neglected in the context of social media research14,16,22 like subjective happiness, mental well-being and fulfilment of basic psychological needs. In answering our research questions we also sought to illustrate how cross-sectional data from a representative population cohort can provide meaningful contextual information that informs the way we interpret past and future research about social media users and their mental health. Unlike other studies using cross-sectional data14 we had no intention of exploring causal questions, but aimed to address unanswered questions of who social media users are, and whether selection bias across platforms may have the potential to unintentionally bias outcome statistics about mental health and well-being.

Specifically, our research questions were:

-

(1)

Are there demographic differences in patterns of social media use (e.g. frequency)?

-

(2)

Are there demographic differences in the user groups of different social media platforms?

-

(3)

Are there differences in the mental health and well-being of those using social media sites at different frequencies?

-

(4)

Are there differences in the mental health and well-being of user groups of different social media platforms?

Methods

Sample description

The sample for this study is drawn from the Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children (ALSPAC)31,32,33. Pregnant women resident in Avon, UK with expected dates of delivery from 1st April 1991 to 31st December 1992 were invited to take part in the study. The initial number of pregnancies enrolled was 14,541. Of these initial pregnancies, 13,988 children were alive at 1 year of age. When the oldest children were ~7 years of age an additional 913 children were enrolled. The total sample size for ALSPAC of children alive at one year of age is 14,901. However, since this time there has been a reduction in the sample due to withdrawals, deaths of those in the cohort and also people simply being lost to follow-up. As such the exact number of participants invited to each data collection activity changes with time. Please note that the ALSPAC study website contains details of all the data that is available through a data dictionary and variable search tool (http://www.bristol.ac.uk/alspac/researchers/our-data/). Study data were collected and managed using REDCap electronic data capture tools hosted at the University of Bristol34.

The analysis presented in this study is based on a sub-sample of 4083 participants who responded to a self-report questionnaire at a mean age of 24 years old in 2016/17. The survey was sent to 9211 currently enrolled and contactable participants, of whom 4345 (47%) returned it. To maintain a consistent sample throughout the following analyses we considered the 4083 observations with complete cases for questions related to self-harm, suicidal thoughts, disordered eating, and social media use, and without the respondents who said that they ‘didn’t know’ whether they had a social media account (n < 5); no respondents stated that they did not have a social media account. As well as the survey at age 24, we considered the responses by those in our main sample to a survey one year previously, at age 23, which collected the well-being measures and the Moods and Feelings Questionnaire, matched to their social media use responses at age 24. This resulted in a sub-sample of 2991 participants who had responded to both surveys. Table 1 gives a comparison of the demographic breakdowns across these samples.

Measures

This study considered the participants’ responses to a range of mental health and well-being measures, as well as demographic data. A brief overview of each of the measures used is given below.

Throughout this paper, we used Male and Female to refer to the participant’s assigned sex at birth. Participant ethnicity was reported by their parent/s, and is available in the data as White, Ethnic Minority Group, or Unknown, where Ethnic Minority Group was only available as one group rather than broken down into specific ethnicities. There were two variables relevant to socio-economic status. The first was whether the participant had achieved an A Level or equivalent qualification by age 20, the second was their parents’ occupation. Parental occupation was measured using the Registrar General’s Social Class schema35, and was collected prior to the birth of the index cohort; we took the higher occupational class of the participant’s parents where available and grouped the overall schema of six categories into those in manual work, and those in non-manual work.

Social media use was measured using three questions. These were: (1) Do you have a social media profile or account on any sites or apps? with possible responses of ‘Yes’, ‘No’ or ‘Don’t know’; (2) Given a list of social media sites, Do you have a page or profile on these sites or apps, and how often do you use them?, where the social media sites were listed and response options were ‘Daily’, ‘Weekly’, ‘Monthly’, ‘Less Than Monthly’ or ‘Never’; (3) How often do you visit any social media sites or apps, using any device? with response options being ‘More than 10 times per day’, ‘2 to 10 times per day’, ‘Once per day’ or ‘Less than once per day’. Here, the definition of ‘social media sites’ in questions (1) and (3) was left to the participant to interpret, whereas in (2) a specific list was provided. In the following analyses, we have summed responses for the use frequencies per platform from question (2) so that ‘Weekly’, ‘Monthly’ and ‘Less than monthly’ are combined to represent ‘Less than daily’.

Depressive symptoms were measured using the short Mood and Feelings Questionnaire (MFQ)36, a 13-item scale that has been validated for measuring depressive symptoms in adolescents37 and in young adulthood38. It asks respondents to rate statements, such as I cried a lot and I thought nobody really loved me, as Not true, Sometimes or True based on how they felt over the past two weeks. Missing items were filled with the mode of the individual’s other responses, provided 50% or more of the items were completed. Scores range from 0 to 26, with a higher score indicating more severe depressive symptoms37. Here we applied a cut-off score of 12 or above as indicating depression38.

Suicidal thoughts were assessed with the question Have you ever thought of killing yourself, even if you would not really do it? with those who indicated that they had ‘within the past year’ being included. Similarly, intentional self-harm was assessed by asking if participants had hurt [themselves] on purpose in any way and we included those who said this had happened at least once within the last year.

Disordered eating was a composite variable that included participants who indicated that they had been told by a healthcare professional that they had an eating disorder (anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, binge eating disorder or another unspecified eating disorder). Participants were also included if they indicated they had engaged in any of the following behaviours at least once a month over the past year with the intention of losing weight or avoiding weight gain: fasting, throwing up, taking laxatives or medication. This classification of disordered eating followed a similar methodology to that used by Micali and colleagues39.

Well-being was measured using seven questionnaires. The Warwick Edinburgh Mental Well-being Scale (WEMWBS) is a fourteen-item questionnaire that has been validated for measuring general well-being in the general population40,41, as well as in young people42,43. It asks respondents to rate statements such as I’ve been dealing with problems well and I’ve been feeling cheerful, on a five-point Likert-type scale. The total score is between 14 and 70. All items in the WEMWBS are positively worded, and it is focused on measuring positive mental health.

The Satisfaction with Life Scale44,45 is five-item questionnaire designed to measure global cognitive judgements of satisfaction with one’s life, which includes statements such as If I could live my life over, I would change almost nothing. Each question uses a seven-point Likert-type measure and the total score is between 5 and 35. The Subjective Happiness Scale46 is a four-item questionnaire based on seven-point Likert-type questions, with the overall score being a mean of the four questions, lying in the range of 1 to 7. Respondents answer questions such as whether they consider themselves to be more or less happy than their peers.

The Gratitude Questionnaire (GQ-6) is a six-item measure that uses a seven-point Likert-type scale to assess individual differences in proneness to experiencing gratitude in daily life47. This scale includes statements such as I have so much in life to be thankful for and I am grateful to a wide variety of people. Each score is summed to a total between 6 and 42. The Life Orientation Test (LOT-R) is a measure of dispositional optimism that has ten items asked on a 5-point Likert-type scale48, though only four of these items are ‘filler’ questions that do not contribute to the final score. The overall score is in the range of 0 to 24, and items that contribute to this include In uncertain times, I usually expect the best and I hardly ever expect things to go my way.

The Meaning in Life questionnaire has 10 items designed to measure two dimensions of meaning in life: (1) Presence of Meaning (how much respondents feel their lives have meaning), and (2) Search for Meaning (how much respondents strive to find meaning and understanding in their lives)49. Statements include I understand my life’s meaning in the Presence sub-scale, and I am looking for something that makes my life feel meaningful in the Search sub-scale. Respondents answered each item on a 7-point Likert-type scale, with the two sub-scales scored in total between 5 and 35.

The psychological constructs of autonomy, competence and relatedness associated with self-determination theory were measured using the Basic Psychological Needs in General (BPN) questionnaire50. This questionnaire has 21 seven-point Likert-style questions with the final score for each of the three sub-domains being the mean of the responses for that sub-domain. As such each of autonomy, competence and relatedness were scored overall from 1 to 7. Example items include People in my life care about me and I often do not feel very capable.

For all measures missing items were filled with the person-level average, provided that half or more of the items were completed. All of the well-being measures listed were scored in a positive direction, where higher scores indicate higher alignment with the construct being measured.

Analysis

The descriptive statistics were calculated using the R programming language (v4.0.1)51 in RStudio (v1.3), primarily using the tidyverse (v1.3.0) package52 for data manipulation and ggplot2 (v3.3.1)53 for visualisation. A reproducible version of the manuscript and supporting code can be found from the Code availability statement.

Ethics

Ethical approval for the study was obtained from the ALSPAC Ethics and Law Committee and the Local Research Ethics Committees. Informed consent for the use of data collected via questionnaires and clinics was obtained from participants following the recommendations of the ALSPAC Ethics and Law Committee at the time. The full list of ethical approval references for ALSPAC can be found on their website (https://www.bristol.ac.uk/alspac/researchers/research-ethics/).

Results

Demographics

We first consider the demographics of social media users across different frequencies of use, and across the five social media platforms: Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, Snapchat and YouTube. These are both taken from the main sample, as described in our ‘Methods’. Table 2 presents the frequency that participants reported using any social media sites each day, based on sex, ethnicity, education, and their parents’ occupational group.

Table 3 gives the percentage of participants from each demographic group who reported being a user of each platform with any use frequency.

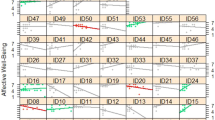

The breakdown of every demographic by frequency of use on each platform is provided in full in Supplementary Table 1. Figure 1 illustrates this breakdown for sex, which is the demographic by which all our following results are stratified due to the imbalance in our sample and the results in Tables 2 and 3. Social media use and mental health and well-being outcomes are also known to vary according to gender54,55,56.

All social media users in the sample (N = 4083) are split by female (N = 2698) and male (N = 1385), and the frequency with which they use each social media platform given as either ‘Daily’, ‘Less than daily’ or ‘Never’. Labels on the stacked charts give the precise percentage of the group in each of the frequencies for each platform.

Mental health and well-being

First we will consider well-being and indicators of poor mental health across different use frequencies. Figure 2 shows how indicators of poor mental health vary across the three frequencies of use, which are more than 10 times a day, 2–10 times a day and once per day or less; no participants reported using no social media at all. These frequencies are contextualised by the prevalence of each outcome in all users of social media. This figure shows that the lowest category of social media use, that is once per day or less, has the highest proportions of disordered eating, self-harm and suicidal thoughts among women. As seen in Table 2, only 7.1% of women and 12% of men used social media less than once per day, and so these measurements are subject to wider confidence intervals. Here, depression is defined as being present in those who scored above the cut-off score of 12 in the Short Mood and Feelings Questionnaire (MFQ)38. Additional descriptive data about mental health outcomes in the sample is also available in Supplementary Figure 1 and in Supplementary Tables 2 to 6.

The frequency with which participants used any social media is reported as ‘more than ten times a day’, ‘between two and ten times a day’ or ‘once or less per day’, and the percentage of participants in that group who reported each mental health outcome is given in each sub-plot, with 95% confidence intervals. Disordered eating, self-harm and suicidal thoughts were assessed in the main sample alongside the social media questions (N = 4083) and included for those participants who reported them in the past year. Depression (N = 2991) was measured in the sub-sample with the Moods and Feelings questionnaire in the year prior to the social media measurement, and uses a cut off of 12 or more to indicate the presence of depression.

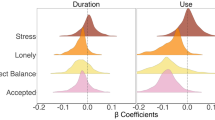

Similarly, each well-being construct is presented in Fig. 3, and contextualised by the result for all users of social media, regardless of frequency. Separate outcomes are presented for the three sub-scales of the Basic Psychological Needs (BPN) scale and the two sub-scales of the Meaning in Life (MIL) scale. The Life Orientation Test measures optimism, and the Warwick Edinburgh Mental Well-being Scale (WEMWBS) measures overall positive well-being.

Each sub-graph presents each of the seven well-being measures, including the Basic Psychological Needs scale (BPN) sub-scales autonomy, relatedness and competence, and the Meaning In Life (MIL) scale’s two sub-scales of presence and search. Satisfaction With Life, the Life Orientation Test, the Gratitude Questionnaire, Subjective Happiness Scale and the Warwick Edinburgh Mental Wellbeing Scale (WEMWBS) are also included. The mean of each scale is given for all participants (N = 2991) with 95% confidence intervals, split by male and female, and then for each dichotomous category of use-frequency which is one of ‘more than ten times a day’, ‘between two and ten times a day’ or ‘once or less per day’.

Next we consider the characteristics of daily users of each platform. The relative percentage of daily users against other types of users for each platform can be referred to in Fig. 1, and versions of Figs. 4 and 5 for all users of each platform are given in Supplementary Figures 2 and 3.

The percentage of daily users of each platform who have reported each symptom is given in each sub-graph, with 95% confidence intervals. Disordered eating, self-harm and suicidal thoughts were assessed in the main sample alongside the social media questions (N = 4083) and included for those participants who reported them in the past year. Depression (N = 2991) was measured in the sub-sample with the Moods and Feelings questionnaire in the year prior to the social media measurement, and uses a cut off of 12 or more to indicate the presence of depression. Participants can belong to the daily user group of more than one platform.

Each sub-graph presents each of the seven well-being measures, including the Basic Psychological Needs scale (BPN) sub-scales autonomy, relatedness and competence, and the Meaning In Life (MIL) scale’s two sub-scales of presence and search. Satisfaction With Life, the Life Orientation Test, the Gratitude Questionnaire, Subjective Happiness Scale and the Warwick Edinburgh Mental Wellbeing Scale (WEMWBS) are also included. The mean of each scale is given for all daily users of each platform from the sub-sample (N = 2991) with 95% confidence intervals, split by male and female.

Finally Fig. 5 gives the mean well-being score across each platform for each of the seven well-being measures.

Discussion

This study used data from a UK population cohort study to describe the demographics and key mental health and well-being indicators of social media users by their self-reported frequency of using social media and five different platforms used at ages 23 and 24. Overall, we saw that there were differences in demographics and mental states of users across use-patterns and platforms used. In the following sections, we detail and discuss the implications of these findings for future research across the themes of demographics, use-frequency and platform used.

In general, just over half of participants reported using social media 2–10 times per day, with more than ten times per day still being common at 39%, and only approximately one in ten participants using social media once per day or less. The results showed that those who rated their social media use at the highest frequency (more than ten times per day) were more likely to be women, more likely to be White and more likely have parents who worked in manual occupations. However, sex was the only demographic that appeared to have a statistical relationship with frequency of use, based on a Chi-squared test. Davies and colleagues57 saw similar results from a Welsh population survey of social media use that found there was a difference in social media use across genders, but not by measures of deprivation.

Figure 1 showed that Facebook is, unsurprisingly, the most popular platform both in being used by 97% of the participants and being the most used platform on a daily basis. Instagram and YouTube showed substantial differences in use patterns across male and female users, with approximately double the percentage of women using Instagram daily as men and, conversely, approximately double the percentage of men using YouTube daily as women. Snapchat also saw higher proportions of daily and overall female users, though this difference between sexes was not as dramatic as for Instagram and YouTube. These patterns of use generally agree with the demographics of users on these sites reported for 18–29-year-old US adults by the Pew Research Center25, although our sample saw slightly more Twitter users than their estimated 38%, and fewer YouTube users than their estimated 91% (see Table 3). This difference in YouTube users may be partly explained by the fact that it is the only platform with a substantially higher proportion of men than women using it (68% of women vs 83% of men), and that men were under represented in our sample overall compared to women. This emphasises the importance of stratifying results by sex.

Previous research into the demographics of UK Twitter users also aligns with our findings that men and people from higher socio-economic backgrounds are more likely to be Twitter users than women26,28. Here, we also saw that those from ethnic minority groups are more likely to be Twitter users than White participants, though this is limited by the fact that we could not further separate out results for people with different ethnicities due to the variables available. Across our sample, Twitter was the only social media platform that had a noticeably higher proportion of both A Level educated participants and parents in non-manual occupations. Snapchat saw the reverse pattern with a higher proportion of participants who did not have A Level qualifications and a higher proportion of participants whose parents worked in manual occupations.

Overall, the sex differences between all male and female users varied across outcomes. For instance, a higher percentage of women experienced depression, disordered eating and self-harm overall, but the gap in the prevalence of suicidal thoughts between men and women was much smaller. This concurs with evidence from the last UK-wide psychiatric morbidity survey, in that ‘common mental health disorders’ are more prevalent in women than men58. When it came to well-being, we saw that women also displayed higher mean levels of well-being across most measures. Exceptions were the Life Orientation Test, which showed men generally had higher levels of optimism, the Subjective Happiness Scale where scores were roughly equivalent, and the WEMWBS where men’s general well-being was slightly higher. These results, apart from the WEMWBS, are consistent with findings on UK-wide well-being at the time of the survey, and that men tend to have higher optimism in general59,60. Previous research into the WEMWBS has not generally found large sex differences, but there is evidence that in younger samples there are differences that may be explained by socio-economic status40,41,61; we note that higher attrition of men in our sample was likely to lead to a bias towards men who are more socio-economically privileged, which may explain why they had higher well-being.

The patterns of mental health outcomes by use frequency displayed in Fig. 2 showed some support for the so-called ‘Goldilocks theory’ of social media use that hypothesises a quadratic, rather than linear, stimulus-response relationship between social media use and mental well-being62. This would mean that moderate use of social media, rather than very little or excessive use, is best for well-being. However, this pattern did not consistently apply. For instance, there was an inverse relationship between social media use and percentage of women who self-harm, and in men only the group with the highest level of social media use had more severe depressive symptoms. Previous research has found that in young women higher social media use was associated with increased risk of self-harm63, which is in contrast to our results. Similarly, research using the Millennium Cohort Study also found an increasing relationship between objectively measured number of hours spent on social media and how many respondents had clinically relevant symptoms of depression64, with a greater increase for girls than boys. Our findings roughly concur with those for the boys, but in women we found that those who used social media the least had the highest rates of depression. However, these differences in findings could reflect the difference in the age of participants or the ways that social media was measured differently across studies. Here we were using use-frequency as categorised into three groups which, as we discuss further in our limitations, may be more reflective of the individual’s mental health and relationship with social media than how frequently they use it65.

When considering the results by well-being measure in Fig. 3 we saw that subjective happiness and optimism as measured by the Life Orientation Test both appeared relatively consistent across use categories. Relatedness presented the clearest difference across use categories, with relatedness in women being higher for the two most frequent use frequencies. However, perhaps the most notable outcome was the inconsistency between well-being scales which implies that the choice of scale could affect the interpretation of the impact of well-being on social media use. Research into the relationship between social media use and well-being has been said to suffer from what is known as the ‘jingle-jangle’ paradox where the term ‘well-being’ is used as a catch-all for anything from depression rates to life satisfaction66,67. This conflation of different well-being measures leads to comparisons of different psychological constructs which may interact differently with social media use: this is hypothesised as one of the reasons that researchers find conflicting evidence for this relationship66, which our results support. This also adds to the picture of researcher degrees of freedom in choosing how to measure psychological constructs, which has been shown to have a substantial impact on the outcome of analyses of social media and mental health15. Subjective well-being is a complex and multi-faceted psychological concept68,69, and these findings illustrate the importance of recognising that different measures of well-being could imply different relationships between social media and “well-being”.

When considering participant outcomes by daily users of each platform more consistent patterns emerge than for use-frequencies. We saw that, particularly for women, YouTube had the highest proportion of users reporting disordered eating, self-harm, suicidal thoughts and depression, with higher prevalence of depression in female users of YouTube compared to male users (Fig. 4). Whilst overall mental well-being across platforms, as measured by the WEMWBS in Fig. 5, shows YouTube as being marginally but not drastically lower than other platforms, other well-being measures illustrated some key differences. For instance, YouTube users had lower life satisfaction, relatedness and, particularly for female users, levels of competence (Fig. 5). Conversely, daily users of Instagram, and in some cases Snapchat, appeared to have the highest subjective well-being across most measures, with this being particularly noticeable for relatedness, gratitude and happiness (Fig. 5). The role of self-determination theory in social media use has previously been explored for Facebook and social media in general70 with relatedness hypothesised as a key motivating factor for social media use. Previous findings have shown that Instagram and Snapchat are used more for social interaction than Twitter and Facebook71, and so our results may corroborate the importance of relatedness in the use of particular platforms. Regardless of the specific measure, our results have illustrated that there is variation amongst platforms which further challenges the idea that ‘social media’ or ‘social networking sites’ are a homogeneous group, and reiterates the importance of understanding the context of research about or using social media28,71.

At face value, our results appear to directly contrast with the outcomes of the Status of Mind report published by the Royal Society for Public Health72, where young people rated YouTube as being the most beneficial site for their well-being and Instagram as the worst, based on health-related outcomes such as their anxiety and depression. Our findings that a higher prevalence of YouTube users suffer from poorer mental health and well-being may mean that whilst some platforms are seen as ‘worse’ for young people’s mental health, that does not equate to finding more unwell young people on those platforms. One explanation may be that those experiencing poorer mental health are more likely to use YouTube because they experience more benefits to their mental health from YouTube, such as community building and peer support13, than they do from spending time on sites like Instagram. However, this is certainly an interesting area for further exploration in future quantitative and qualitative research.

Whilst this research draws evidence from a robust and well-documented study and the sample being from a birth cohort means that our results are not confounded by age, there are limitations to the cohort sample that we have used. Firstly, the cohort measures a specific age group so we can only infer information about a single age group at each measurement time point. We suspect that different patterns might be found at different ages, knowing that rates of various mental health conditions such as anxiety, depression and suicidality change over the course of childhood, adolescence and adulthood73, and since each generation may use social media differently74. It is also important to note that the two data collection points used in this study were taken a year apart, and so not all measures were taken exactly at the same time. This means that although we have primarily considered the data cross-sectionally there is a potential for some longitudinal effects to have influenced the data. Secondly, as discussed in the ‘Methods’ section, there was also a limitation in that ethnicity was only available as two categories (White or Ethnic Minority Groups) and so it was not possible to look further into differences in social media by users of difference ethnicities. Additionally, the make up of the area of Bristol that ALSPAC represents is predominantly White. Given these limitations of the sample it would be valuable to conduct similar research in other cohorts that represent more diverse areas. Thirdly, ALSPAC has seen differential attrition over time and so, as seen in Table 1, the sample for this study when the index cohort were in their early twenties has fewer men than women, and more participants from privileged socio-economic groups in terms of education and class background31. As well as this, typical social media use changes over time and by age25, and so further assessment of social media use across a variety of population-representative age groups would be the most effective way to understand differences between generations.

Another limitation of this study is a lack of specificity about the nature of social media use that participants are referring to when responding. It is possible that activities related to ‘using’ social media, such as posting content versus passive use, change depending on platform used and that there are individual preferences to account for54,71,75,76. For instance, YouTube is distinct from other platforms in this study in that its primary function is passive content consumption as opposed to social networking. Previous research has suggested a reciprocal association between passive social media use and lower subjective well-being75, whilst using social media for direct communication has been positively associated with perceived friend support77. This may better reflect the uses of platforms like Snapchat. As well as the subjective nature of ‘use’, there are also ongoing concerns about using self-reported measures of use-frequency to measure social media behaviours78,79,80. Emerging evidence is showing that self-reports do not align well with objective measurement due to recall bias and differences in interpreting how to include notifications or fleeting checks of social media79,80 with self-reported smartphone pickups underestimating associations with mental health compared to objective measures of use65. It might be that different ways of measuring social media use, such as types of use, are more useful when considering associations with mental health and well-being outcomes54. It is worth noting that the use-frequency measures used in this study are distinct from screen-time, and equivalent use-frequency across platforms may have different time implications; someone may spend short amounts of time on Instagram or Snapchat checking notifications, but do so frequently, versus visiting YouTube once in a day but spending several hours watching content. These nuances are challenging to capture, but by reporting on mental health prevalence across the available responses in a cohort study we can add to the growing understanding of how self-reported social media use frequency is related to mental health. Statistical modelling to test the extent of the differences observed between mental health constructs, use-frequencies and platforms would be valuable future research.

In summary, our results amplify the importance of attending to complexity when measuring and analysing social media use and mental health and well-being. It is important to note that our results do not, and cannot, imply that different types of social media use cause poorer or better health outcomes in young people, but they do provide vital contextual information on user groups that can help us better understand the reasons that previous research has found conflicting results. We have provided estimates of seven well-being measures and the prevalence of four key mental health outcomes (depression, disordered eating, suicidal thoughts and self-harm) across the five platforms Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, Snapchat and YouTube, as well as across three use frequencies. Our findings have shown that the demographic and mental health foot-print of each platform is different. Primarily users differ by sex, but when it comes to platforms YouTube is particularly likely to have both male and female users with poorer mental health and well-being across a range of indicators, alongside evidence that daily Instagram users have better overall well-being than daily users of other platforms. Our findings also indicate that relationships between use-frequency and multiple mental health and well-being outcomes are often non-linear, which supports the importance of considering non-linear dose-response relationships between social media and mental health and well-being in future research. Lastly, we saw that the relationship between use-frequencies and well-being changes depending on the measure of well-being used. This means that we cannot conflate different types of well-being, and doing so will likely result in low replicability.

This research has implications for both those who conduct research on the relationship between social media and mental health, and those who study mental health prediction. We must ensure we are considering both platform-specific and outcome-specific effects rather than conflating types of social media use, social media sites and well-being as single entities. Future research should also stratify results by sex since it is unlikely that studies with differently balanced samples will replicate. Our findings on use-frequencies also suggest that we cannot assume linear relationships between social media use and mental health. Our understanding of these methodological issues would be improved by examining profiles of different user age-groups, as well as examining relationships between these variables longitudinally to understand the potential for reciprocal effects. The differences between platforms should be further considered too, as to how different content types and communication modes on different platforms may affect mental health differently.

Data availability

The datasets analysed during the current study are not publicly available as the informed consent obtained from ALSPAC participants does not allow data to be made freely available through any third party maintained public repository. However, data used for this submission can be made available on request to the ALSPAC Executive, with reference to project number B3227. The ALSPAC data management plan describes in detail the policy regarding data sharing, which is through a system of managed open access. Full instructions for applying for data access can be found here: http://www.bristol.ac.uk/alspac/researchers/access/. The ALSPAC study website contains details of all the data that are available (http://www.bristol.ac.uk/alspac/researchers/our-data/).

Code availability

The code used to produce the results in this study can be found at https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/RKXM6.

References

Bayer, J. B., Trieu, P. & Ellison, N. B. Social media elements, ecologies, and effects. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 71, 471–497 (2020).

Carr, C. T. & Hayes, R. A. Social media: defining, developing, and divining. Atl. J. Commun. 23, 46–65 (2015).

Office for National Statistics. Internet Access: Households and Individuals (2020).

Chancellor, S. & De Choudhury, M. Methods in predictive techniques for mental health status on social media: a critical review. NPJ Digit. Med. 3, 1–11 (2020).

Hollis, C., Livingstone, S. & Sonuga-Barke, E. The role of digital technology in children and young people’s mental health—a triple-edged sword? J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpp.13302 (2020).

Dubicka, B. & Theodosiou, L. Technology Use and the Mental Health of Children and Young People. https://www.rcpsych.ac.uk/docs/default-source/improving-care/better-mh-policy/college-reports/college-report-cr225.pdf (2020).

Lee, K. S. et al. Advanced daily prediction model for national suicide numbers with social media data. Psychiatry Investig. 15, 344 (2018).

Roy, A. et al. A machine learning approach predicts future risk to suicidal ideation from social media data. NPJ Digit. Med. 3, 1–12 (2020).

Santarossa, S. & Woodruff, S. J. # SocialMedia: exploring the relationship of social networking sites on body image, self-esteem, and eating disorders. Soc. Media Soc. 3, 2056305117704407 (2017).

Arendt, F., Scherr, S. & Romer, D. Effects of exposure to self-harm on social media: evidence from a two-wave panel study among young adults. New Media Soc. 21, 2422–2442 (2019).

Hamm, M. P. et al. Prevalence and effect of cyberbullying on children and young people: a scoping review of social media studies. JAMA Pediatr. 169, 770–777 (2015).

Craig, W. et al. Social media use and cyber-bullying: a cross-national analysis of young people in 42 countries. J. Adolesc. Health 66, S100–S108 (2020).

Naslund, J. A., Grande, S. W., Aschbrenner, K. A. & Elwyn, G. Naturally occurring peer support through social media: the experiences of individuals with severe mental illness using YouTube. PLOS ONE 9, e110171 (2014).

Schønning, V., Hjetland, G. J., Aarø, L. E. & Skogen, J. C. Social media use and mental health and well-being among adolescents—a scoping review. Front. Psychol. 11, 1949 (2020).

Orben, A. & Przybylski, A. K. The association between adolescent well-being and digital technology use. Nat. Hum. Behav. 3, 173–182 (2019).

Orben, A. Teenagers, screens and social media: A narrative review of reviews and key studies. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 55, 407–414 (2020).

Appel, M., Marker, C. & Gnambs, T. Are social media ruining our lives? A review of meta-analytic evidence. Rev. Gen. Psychol. 24, 60–74 (2020).

Coyne, S. M., Rogers, A. A., Zurcher, J. D., Stockdale, L. & Booth, M. Does time spent using social media impact mental health?: an eight year longitudinal study. Comput. Hum. Behav. 104, 106160 (2020).

Primack, B. A., Shensa, A., Sidani, J. E., Escobar-Viera, C. G. & Fine, M. J. Temporal associations between social media use and depression. Am. J. Prev. Med. 60, 179–188 (2021).

Valkenburg, P., Beyens, I., Pouwels, J. L., Driel, I. I. van & Keijsers, L. Social media use and adolescents’ self-esteem: heading for a person-specific media effects paradigm. J. Commun. https://doi.org/10.1093/joc/jqaa039 (2021).

Beyens, I., Pouwels, J. L., Driel, I. I. van, Keijsers, L. & Valkenburg, P. M. The effect of social media on well-being differs from adolescent to adolescent. Sci. Rep. 10, 1–11 (2020).

Weinstein, E. The social media see-saw: positive and negative influences on adolescents’ affective well-being. New Media Soc. 20, 3597–3623 (2018).

Guntuku, S. C., Yaden, D. B., Kern, M. L., Ungar, L. H. & Eichstaedt, J. C. Detecting depression and mental illness on social media: An integrative review. Curr. Opin. Behav. Sci. 18, 43–49 (2017).

Amir, S., Dredze, M. & Ayers, J. W. Mental health surveillance over social media with digital cohorts. In Proceedings of the Sixth Workshop on Computational Linguistics and Clinical Psychology 114–120 (2019).

Center, Pew Research. Demographics of Social Media Users and Adoption in the United States (2021).

Sloan, L. Who tweets in the united kingdom? Profiling the Twitter population using the British social attitudes survey 2015. Soc. Media Soc. 3, 2056305117698981 (2017).

Sloan, L., Morgan, J., Burnap, P. & Williams, M. Who tweets? Deriving the demographic characteristics of age, occupation and social class from Twitter user meta-data. PLoS ONE 10, e0115545 (2015).

Mellon, J. & Prosser, C. Twitter and Facebook are not representative of the general population: political attitudes and demographics of British social media users. Res. Politics 4, 2053168017720008 (2017).

Heckman, J. J. Sample selection bias as a specification error. Econometrica: J. Econometric Soc. 153–161. https://doi.org/10.2307/1912352 (1979).

Aguirre, C., Harrigian, K. & Dredze, M. Gender and racial fairness in depression research using social media. In The 16th Conference of the European Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics (2021).

Boyd, A. et al. Cohort profile: The “children of the 90 s”—the index offspring of the Avon longitudinal study of parents and children. Int. J. Epidemiol. 42, 111–127 (2013).

Fraser, A. et al. Cohort profile: the Avon longitudinal study of parents and children: ALSPAC mothers cohort. Int. J. Epidemiol. 42, 97–110 (2013).

Northstone, K. et al. The Avon longitudinal study of parents and children (ALSPAC): an update on the enrolled sample of index children in 2019. Wellcome Open Res. 4, 51 (2019).

Harris, P. A. et al. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)—a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J. Biomed. Inform. 42, 377–381 (2009).

Szreter, S. R. The genesis of the registrar-general’s social classification of occupations. Brit. J. Soc. 522–546. https://doi.org/10.2307/590433 (1984).

Costello, E. J. & Angold, A. Scales to assess child and adolescent depression: checklists, screens, and nets. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 27, 726–737 (1988).

Angold, A. et al. Development of a short questionnaire for use in epidemiological studies of depression in children and adolescents: factor composition and structure across development. Int. J. Methods Psychiatr. Res. 5, 237–249 (1995).

Eyre, O. et al. Validation of the short Mood and Feelings Questionnaire in young adulthood. J. Affect. Disord. 294, 883–888 (2021).

Micali, N. et al. Eating disorder behaviours amongst adolescents: investigating classification, persistence and prospective associations with adverse outcomes using latent class models. Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 26, 231–240 (2017).

Tennant, R. et al. The Warwick-Edinburgh mental well-being scale (WEMWBS): development and UK validation. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 5, 63 (2007).

Ng Fat, L., Scholes, S., Boniface, S., Mindell, J. & Stewart-Brown, S. Evaluating and establishing national norms for mental wellbeing using the short Warwick–Edinburgh mental well-being scale (SWEMWBS): findings from the health survey for England. Qual. Life Res. 26, 1129–1144 (2017).

Ringdal, R., Bradley Eilertsen, M.-E., Bjørnsen, H. N., Espnes, G. A. & Moksnes, U. K. Validation of two versions of the Warwick-Edinburgh mental well-being scale among Norwegian adolescents. Scand. J. Public Health 46, 718–725 (2018).

McKay, M. T. & Andretta, J. R. Evidence for the psychometric validity, internal consistency and measurement invariance of Warwick Edinburgh mental well-being scale scores in Scottish and Irish adolescents. Psychiatry Res. 255, 382–386 (2017).

Diener, E., Emmons, R. A., Larsen, R. J. & Griffin, S. The satisfaction with life scale. J. Pers. Assess. 49, 71–75 (1985).

Pavot, W. & Diener, E. The satisfaction with life scale and the emerging construct of life satisfaction. J. Posit. Psychol. 3, 137–152 (2008).

Lyubomirsky, S. & Lepper, H. S. A measure of subjective happiness: preliminary reliability and construct validation. Soc. Indic. Res. 46, 137–155 (1999).

McCullough, M. E., Emmons, R. A. & Tsang, J.-A. The grateful disposition: a conceptual and empirical topography. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 82, 112 (2002).

Scheier, M. F., Carver, C. S. & Bridges, M. W. Distinguishing optimism from neuroticism (and trait anxiety, self-mastery, and self-esteem): a reevaluation of the life orientation test. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 67, 1063 (1994).

Steger, M. F., Frazier, P., Oishi, S. & Kaler, M. The meaning in life questionnaire: assessing the presence of and search for meaning in life. J. Couns. Psychol. 53, 80 (2006).

Deci, E. L. & Ryan, R. M. The” what” and” why” of goal pursuits: human needs and the self-determination of behavior. Psychol. Inq. 11, 227–268 (2000).

R Core Team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, 2020).

Wickham, H. et al. Welcome to the tidyverse. J. Open Source Softw. 4, 1686 (2019).

Wickham, H. ggplot2: Elegant Graphics for Data Analysis (Springer-Verlag, 2016).

Winstone, L., Mars, B., Haworth, C. M., Heron, J. & Kidger, J. Adolescent social media user types and their mental health and well-being: results from a longitudinal survey of 13–14-year-olds in the United Kingdom. https://doi.org/10.31234/osf.io/cg86n (2021).

Boyd, A. et al. Gender differences in mental disorders and suicidality in Europe: results from a large cross-sectional population-based study. J. Affect. Disord. 173, 245–254 (2015).

Matud, M. P., López-Curbelo, M. & Fortes, D. Gender and psychological well-being. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 16, 3531 (2019).

Davies, A., Song, J. & Sharp, C. Social media engagement and health. Int. J. Popul. Data Sci. 4 https://doi.org/10.23889/ijpds.v4i3.1278 (2019).

McManus, S., Bebbington, P. E., Jenkins, R. & Brugha, T. Mental Health and Wellbeing in England: the Adult Psychiatric Morbidity Survey 2014. https://files.digital.nhs.uk/pdf/q/3/mental_health_and_wellbeing_in_england_full_report.pdf (2016).

Tabor, D. & Stockley, L. Personal Well-being in the UK: October 2016 to September 2017. https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/wellbeing/bulletins/measuringnationalwellbeing/october2016toseptember2017 (2018).

Glaesmer, H. et al. Psychometric properties and population-based norms of the life orientation test revised (LOT-r). Brit. J. Health Psychol. 17, 432–445 (2012).

Clarke, A. et al. Warwick-Edinburgh mental well-being scale (WEMWBS): Validated for teenage school students in England and Scotland. A mixed methods assessment. BMC Public Health 11, 487 (2011).

Przybylski, A. K. & Weinstein, N. A large-scale test of the goldilocks hypothesis: quantifying the relations between digital-screen use and the mental well-being of adolescents. Psychol. Sci. 28, 204–215 (2017).

Barthorpe, A., Winstone, L., Mars, B. & Moran, P. Is social media screen time really associated with poor adolescent mental health? A time use diary study. J. Affect. Disord. 274, 864–870 (2020).

Kelly, Y., Zilanawala, A., Booker, C. & Sacker, A. Social media use and adolescent mental health: findings from the UK millennium cohort study. EClinicalMedicine 6, 59–68 (2018).

Shaw, H. et al. Quantifying smartphone ‘use’: choice of measurement impacts relationships between ‘usage’ and health. Technol. Mind Behav. 1 https://doi.org/10.1037/tmb0000022 (2020).

Kross, E. et al. Social media and well-being: Pitfalls, progress, and next steps. Trend. Cog. Sci. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2020.10.005 (2020).

Meier, A. & Reinecke, L. Computer-mediated communication, social media, and mental health: a conceptual and empirical meta-review. Commun. Res. https://doi.org/10.1177/0093650220958224 (2020).

Diener, E., Oishi, S. & Tay, L. Advances in subjective well-being research. Nat. Hum. Behav. 2, 253–260 (2018).

Lin, J.-H. Need for relatedness: a self-determination approach to examining attachment styles, facebook use, and psychological well-being. Asian J. Commun. 26, 153–173 (2016).

Berezan, O., Krishen, A. S., Agarwal, S. & Kachroo, P. The pursuit of virtual happiness: exploring the social media experience across generations. J. Bus. Res. 89, 455–461 (2018).

Alhabash, S. & Ma, M. A tale of four platforms: motivations and uses of Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, and Snapchat among college students? Soc. Media Soc. 3, 2056305117691544 (2017).

Royal Society for Public Health. StatusOfMind: Social Media and Young People’s Mental Health and Wellbeing. https://ed4health.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2018/12/RSPH-Status-of-Mind-report.pdf (2018).

Maughan, B., Collishaw, S. & Stringaris, A. Depression in childhood and adolescence. J. Can. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 22, 35 (2013).

Di Cara, N. H. et al. Views on social media and its linkage to longitudinal data from two generations of a UK cohort study. Wellcome Open Res. 5 https://doi.org/10.12688/wellcomeopenres.15755.2 (2020).

Wang, J.-L., Gaskin, J., Rost, D. H. & Gentile, D. A. The reciprocal relationship between passive social networking site (SNS) usage and users’ subjective well-being. Soc. Sci. Comput. Rev. 36, 511–522 (2018).

Winstone, L., Mars, B., Haworth, C. M. & Kidger, J. Types of social media use and digital stress in early adolescence. J. Early Adolesc. https://doi.org/10.1177/02724316221105560 (2022).

Frison, E. & Eggermont, S. Toward an integrated and differential approach to the relationships between loneliness, different types of Facebook use, and adolescents’ depressed mood. Commun. Res. 47, 701–728 (2015).

Scharkow, M. The accuracy of self-reported internet use—a validation study using client log data. Commun. Methods Meas. 10, 13–27 (2016).

Ernala, S. K., Burke, M., Leavitt, A. & Ellison, N. B. How well do people report time spent on Facebook? An evaluation of established survey questions with recommendations. In Proceedings of the 2020 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems 1–14 (2020).

Parry, D. A. et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis of discrepancies between logged and self-reported digital media use. Nat. Hum. Behav. 5, 1535–1547 (2021).

Acknowledgements

We are extremely grateful to all the families who took part in this study, the midwives for their help in recruiting them, and the whole ALSPAC team, which includes interviewers, computer and laboratory technicians, clerical workers, research scientists, volunteers, managers, receptionists and nurses. The UK Medical Research Council and Wellcome (Grant ref: 217065/Z/19/Z) and the University of Bristol provide core support for ALSPAC. A comprehensive list of grants funding is available on the ALSPAC website (http://www.bristol.ac.uk/alspac/external/documents/grant-acknowledgements.pdf). The data used in this research was specifically funded by the NIHR (1215-20011), the Wellcome Trust (SSCM.RD1809) and the MRC (102215/2/13/2, MR/M006727/1). N.D. is supported by an MRC GW4 BioMed studentship in Data Science and AI (MR/N013794/1). C.M.A.H. is supported by a Philip Leverhulme Prize. N.H., O.S.P.D. and C.M.A.H. will serve as guarantors for the contents of this paper.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

N.D. was responsible for data curation, formal analysis, investigation, methodology, visualisation and writing (original draft and reviewing and editing). L.W. was responsible for methodology, investigation and writing (reviewing and editing). L.S. was responsible for methodology, investigation, supervision and writing (reviewing and editing). O.D. and C.H. were responsible for funding acquisition, conceptualisation, methodology, investigation, supervision and writing (reviewing and editing).

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Di Cara, N.H., Winstone, L., Sloan, L. et al. The mental health and well-being profile of young adults using social media. npj Mental Health Res 1, 11 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s44184-022-00011-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s44184-022-00011-w