Abstract

The global scientific community is currently going through a self-reckoning in which it is questioning and re-examining its existing practices, many of which are based on colonial and neo-colonial perceptions. This is particularly acute for the ocean research community, where unequal and unbalanced international collaborations have been rife. Consequently, numerous discussions and calls have been made to change the current status quo by developing guidelines and frameworks addressing the key issues plaguing our community. Here, we provide an overview of the key topics and issues that the scientific community has debated over the last three to four years, with an emphasis on ocean research, coupled with actions per stakeholder groups (research community, institutions, funding agencies, and publishers). We also outline some key discussions that are currently missing and suggest a path forward to tackle these gaps. We hope this contribution will further accelerate efforts to bring more equity and justice into ocean sciences.

Similar content being viewed by others

Is the ocean science community equitable?

Globally, there are growing calls for the scientific community to dismantle and reform its business-as-usual practices based on unbalanced and unequal international partnerships between researchers from high-income economies in the Global North and low to middle-income economies in the Global South1. Known as parachute science2,3, this colonial model of research perpetuates and widens inequalities, provides little to no tangible benefit to researchers from under-resourced countries, and often overlaps with and impacts locally-led efforts. This is prevalent in ocean science, where international collaborations are the norm, given the expensive and complex nature of operations, the connected nature of our oceans, and the global threats (e.g., climate change, pollution, transnational fisheries) they face today4,5. Ignoring social inequities in conservation can result in social harms but also undermines local expertise, thereby hindering the potential for conservation success6.

The global COVID-19 pandemic exposed geographic inequalities in healthcare access and vaccine distribution. At the same time, grassroots social movements such as Black Lives Matter highlighted systemic racism rooted in colonial and neo-colonial perceptions. These played a significant role in the collective shift in perspective, forcing many of us in the research community to take a hard look at how we have and continue operating2.

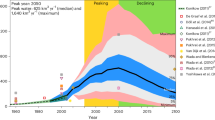

Consequently, since 2020, there has been a plethora of publications addressing those issues. For example, an online search on the Scopus database using terms related to ocean equity and justice indicated that 60% of publications were published in the last ~3.5 years (Fig. 1). Apart from literature, during the same period, there were numerous webinars held, as well as round-table events at workshops and conferences, including high-level events such as the United Nations (UN) Oceans conference, which specifically focussed on finding solutions that would help achieve diversity, equity and inclusivity (DEI) in the ocean space. This is significant given that high-level conferences are non-equitable by their very nature and must be transformed into more inclusive meetings where location, modality, leadership and participation enable diversity and equity of voice 7,8. The UN Decade of Ocean Science attempts to support efforts to bring more equity and justice into the ocean through its statement ‘leave no one behind’. It provides i) a focus for funders to support diverse participation in ocean stewardship (e.g., AXA Research Fund), ii) a platform for networking and publicity (e.g., Empowering Women in Hydrography; ECOP DEI Initiative), iii) an opportunity to advertise successes (e.g., MeerWissen podcast of African early-career researchers) and iv) guidance for best-practices9. However, only time will tell if these initiatives develop into a legacy of more equitable science.

Number of peer-reviewed publications in Scopus (https://www.scopus.com) that had either one of the following keywords in their abstract, title and/or keywords section (“ocean equity”, “ocean justice”, “marine justice”, “blue justice”) or the following combination of keywords in their title (“colonial science”, “ethical”, “equality”, “equity”, “justice”, “inclusivity”, “parachute science”, “racism”, “underrepresented”; in combination with either “ocean”, “marine”, and “deep sea”). Only searches in the title were used for the latter combination of keywords, to minimise false positive results. Total number of publications = 154. Date accessed: 02.08.2023.

The present authorship has led or been involved in many efforts to improve equity in ocean science but struggled to keep track of the latest developments. Hence, it is important to review the latest discussions around these topics. We hope that researchers interested in achieving ocean equity and justice can use this as an initial resource to learn more about these subjects and the voices leading the conversations around them. Furthermore, we identify aspects that have not yet been addressed or deserve more attention and discussion and suggest a path to tackle these gaps.

How can we make the ocean research community more equitable and just?

To address our objective, we performed a scoping review of scholarly literature and online resources focusing on ocean equity and justice. However, broader equity discussions from other fields were included if they applied to the ocean research community. The list of references cited is non-exhaustive, instead we selectively present references that provide novel critical perspectives or introduce new concepts. For ease of navigation, we organise literature findings across five broad themes: “Reshaping education, perceptions, attitudes, and working environments”, “Rebalancing partnerships and collaborations”, “Science analysis and publication”, “Strengthening capacity”, and “Networking and public engagement”, with additional sub-divisions within each theme. A concise summary in Table 1 is linked with a series of actions across different sectors (Research Community, Institutions, Funding Agencies, and Publishers) that we believe would help change the status quo.

Reshaping education, perceptions, attitudes, and working environments

Justice and equity can only be achieved if the appropriate support systems are in place to remove barriers and bias, and existing policies are reevaluated and redesigned to ensure zero tolerance towards harassment and discrimination of all minority and underrepresented groups.

Anti-racist interventions

Racial and ethnic discrimination results in the marginalisation and continued active exclusion of Black, Indigenous, and People of Colour (BIPOC) in the ocean sciences10. Conscious and unconscious biases around individual capacity related to place of origin and racial or ethnic background limit the contributions of some, while also unfairly elevating those in positions of power and privilege. Metrics of success should meaningfully represent an individual’s capacity to resolve our existing planetary and ocean challenges11. Educating oneself on the history of racism and discrimination, and acknowledging racist history and barriers, while reflecting on individual positionality and using individual privilege to advocate for and create opportunities for those from underrepresented groups is a first yet significant step12,13. Funders can ensure funding does not exacerbate unequal power dynamics by requesting DEI statements and evaluating their impact, increasing opportunities for more diverse grant reviewers, and removing barriers for such efforts (e.g., providing remuneration). Publishers can also request DEI statements and create opportunities by including open calls for more diverse reviewers and editors while being mindful of the ‘Minority Tax’ (i.e., the burden placed on ethnic minority faculty to fix the DEI problem)14. Further, offering mentorship through the review process can also alleviate barriers to participation.

Be inclusive of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, Queer, Intersex and Asexual (LGBTQIA+ ) researchers

Much like with anti-racist interventions, actively supporting and promoting researchers from these minority groups as speakers, collaborators, reviewers, editors, and lecturers based on their capacity broadens the conversations and our opportunities to drive change15. Using appropriate language during the article submission process and allowing for invisible name changes retrospectively can go a long way to preserve the dignity of transgender researchers16,17. It is also essential that codes of conduct include unambiguous anti-harassment and anti-bullying policies that unequivocally protect all underrepresented groups.

Eradicate gender discrimination

Minority groups are not the only groups that face discrimination in ocean sciences. While women make up 39% of the ocean science research population18, they face challenges related to promotions, unequal pay and opportunities while also facing safety issues in the field19. Support systems and programmes should be designed to encourage the long-term participation of women and other underrepresented groups in ocean sciences. There is also a growing body of work showing strong gender bias in authorship and who is being cited11,20,21.

Ensure safe working practices

Safe working practices and spaces are fundamental rights that should be equally afforded to all researchers. However, incidents of harassment and bullying are still reported in ocean science and are more likely to affect women22,23 or other underrepresented groups, especially when working in remote locations or isolated settings such as on a vessel19,24. Laboratories, projects, expeditions etc., should develop codes of conduct that provide clear guidelines for expected behaviour that are disseminated for endorsement amongst all team members to ensure unequivocal buy-in. These codes should outline mandatory, safe, and confidential mechanisms for the reporting and handling of incidents of racism, sexism and other forms of discrimination19,23.

Rebalancing partnerships and collaborations

Making space for and supporting all forms of knowing and all partners to work towards a common end goal equitably is imperative to increasing justice in ocean sciences.

Co-development and co-production of international scientific projects

This is necessary to maximise beneficial outcomes for all parties involved. To be successful, engagement between international and local collaborators should start well in advance of research or fieldwork commencing to ensure time to build trust, share information, co-design the research, equitably allocate funding and identify needs and priorities on the ground that could benefit from the collaboration25,26. This truly collaborative approach must continue post-fieldwork through all subsequent stages of the project, including data analysis, publication of results and dissemination of findings 27.

Equitable and power-balanced partnerships require time, resources, and commitment from all sides as well as flexible models of work that permit adaptation to changing aspects such as organisational needs, timelines, and outputs27. Consequently, institutions should reward researchers engaging in such practices the same way they reward other scholarly work, and specific training should be provided with resources in place to support transition in research practices and the challenges that are encountered. Funding agencies should encourage and support truly co-designed projects with dedicated funds that allow knowledge exchange activities to occur.

Respect for Indigenous and local knowledge

Most established research methods in ocean science have their roots in Western philosophy and thinking due to centuries of Euro-American colonialism. This has led to a wealth of knowledge residing in Indigenous and local communities often being undervalued or overlooked with detrimental consequences for the marine environment and missed opportunities for innovative solutions28,29. Acknowledging this intellectual power imbalance is an important and necessary first step. However, alone this is insufficient, and additional actions must be taken to ensure all pools of knowledge and ways of knowing are considered30. For example, researchers should conduct qualifying assessments for individuals to demonstrate ‘cultural literacy’ about fieldwork locations10 and research topics. Research projects must consider the inclusion of Indigenous scholars from those foci who are better placed to interpret culture and historical context, and understand the significance of information. Indigenous scholars are also better able to identify when it is inappropriate to publish information or data sacred to Indigenous Peoples or communities. It is also important to ensure that when such knowledge is shared, it is not taken, repurposed and exploited in a way damaging to the knowledge providers or their culture and traditions.

Science analysis and publication

Making space for non-native English speakers by establishing inclusive practices, encouraging and rewarding diverse forms of science communication, and recognising and highlighting existing locally-led research and knowledge is imperative to achieving ocean justice and equity.

Consider non-English languages

Professional advancement in science is tied to publishing in English language peer-reviewed journals. For many in the Global South and other non-native speakers of English, this presents challenges. Creating opportunities to close the gap, and thereby support capacity growth of local partners is imperative. Publishing a local language summary as an accompaniment to a full paper in a peer-reviewed journal prevents assumptions that no work is being conducted locally31 and makes findings more accessible. In addition, international collaborations allow researchers to tap into non-English literature that is otherwise overlooked, and have been shown to result in better data products for conservation science32,33. Alternatively, machine translation tools, while still not perfect, serve as both a short and long-term solution for making science more accessible and impactful34.

Diversity of literature cited

Very often, science cites popular research or research published by scientists (largely men) in the Global North while overlooking knowledge bases from other geographies20,35. Researchers should add a citation diversity statement, actively educate themselves on the work of underrepresented local scientists in their relevant fields of study and cite them, and check for gender balance in reference lists.

Inclusive authorships

To avoid the exclusion of authors from papers3, authorship should recognise and credit all contributors and also reflect contributions that extend beyond the usual data collection, analysis and writing stages36. A more inclusive approach to authorship recognises and values diverse contributions and contributors without whom the work could not have occurred20. The emphasis on an equitable process rather than system and equality, results in authorship lists that recognise non-traditional authorship roles (field and research assistants), and consider intersectional social standing37.

Make research visible and discoverable

Eighty percent of academic research is publicly funded or funded through charities, but most articles are locked behind paywalls38. This blocks access to scientists and practitioners who are best placed to use the research in beneficial ways39. This in turn hinders scientific progress as it is difficult to build and resolve in the absence of foundational knowledge. While open-access publishing presents a viable solution, there is a need to ensure that the burden of payment does not fall on those that are unable to pay and that models exist to overcome these challenges38. Article Publishing Charges (APCs) in prestigious journals with a wide public reach are often so high that they are only affordable by better-resourced researchers. For example, the APC fee for a single, high-impact journal can cost the equivalent of many months’ salary for researchers in the Global South40, thus hampering research visibility of poorly funded researchers—often early career and Global South researchers—who opt to then publish in less visible journals—if at all41,42. This then leads to a disparity in research profiles43. To overcome these costs, institutions and funders can encourage and support research publication in Diamond Open Access journals that are community-driven, academic-led, and academic-owned publishing initiatives that do not charge fees from authors or readers42. Transforming the traditional publishing system is necessary. Thus, continued dialogue and negotiations between institutions, funders and academic publishers is a way of advancing towards solutions. Further, researchers should be required to prepare easy-to-understand summaries of their publications for sharing on social and traditional media to broaden the audience and increase visibility and potential use. Aside from peer-reviewed publications, researchers should explore whether producing additional locally tailored communication outputs (e.g., infographics, story maps, exhibitions, Science Technology Engineering and Mathematics (STEM) activities) will, in some cases, be more appropriate and impactful.

Strengthening capacity

Recognising existing capacity and investing in partners, partnerships, and infrastructure ensures projects are best equipped to drive sustainable and impactful change.

Invest in human capacity

Successful projects acknowledge the importance of ‘capacity-sharing’1, where locals lead with their knowledge on the ground and existing priorities, and technical capacity is enhanced through collaboration with the outside team44,45. Reframing the term capacity-building creates space for more equity in partnerships and acknowledges, recognises and maximises the use of skill sets available within the team. Projects should also incorporate efforts to actively build the technical capacity of researchers from underrepresented communities and coastlines based on their needs through increased availability of grants and training programmes. Furthermore, while data should be deposited in the country where it was collected, training and discussions on how to use these data maximally should also be provided to local researchers. Funding should be secured to support analysis and data usage locally to ensure long-term project sustainability.

Invest in infrastructure capacity (including low-cost technology options)

Ocean research is often inequitably focused in areas where marine infrastructure availability is highest3,46. The co-development of research facilities and low-cost tools with the community of practitioners allows a broader segment of scientific society to contribute, explore and discover while also breaking down barriers unnecessarily placed on individuals based on where they come from47. A co-designed approach also facilitates ease of local repair and adaptation when needed. This could be improved by conducting field tests of prototypes in conjunction with teams from less equipped countries47. Additionally, mentorship on entrepreneurship and innovation could encourage the use of existing infrastructure to develop technologies from locally available resources.

Networking and public engagement

Engaging the diversity of voices and capacities contributes to ocean conservation and ensures access to scientific knowledge, and networks that inevitably drive equity and justice in the ocean sciences.

Widen participation in networking and scientific dissemination opportunities

Conferences are traditionally conducted in the Global North at times best suited for the scientific community from that part of the world. Unfortunately, this precludes the participation of researchers from the Global South, who are most often inequitably hindered by expensive attendance fees, visa issues, travel and accommodation costs. Online-only or online-accessible (hybrid) meetings are an effective way to widen participation compared to in-person-only conferences with an increase in participation of 33–74% and increased geographic representation of 28–38%48,49,50. However, they are not a panacea and should not completely replace in-person meetings that provide face-to-face interactions that are important for building long-lasting relationships. A more effective way to widen participation would be to host meetings in low and middle-income economies49 (e.g., International Symposium on Deep-Sea Corals in 2019 in Cartagena, Colombia; International Marine Conservation Congress in 2018 in Sarawak, Malaysia; International Congress for Conservation Biology in 2023 in Kigali, Rwanda) with logistical and financial support provided as necessary to participating researchers and institutions.

Decolonise the Ocean Narrative/Local Ocean Champions

Seventy percent of coastlines are in the Global South. Realistically, if we are to manage and protect our ocean sustainably, we need to ensure that every coastline has a local champion that can support and engage in efforts to drive change for a healthy ocean of the future2. Giving underrepresented groups a seat at the negotiating table ensures that the diversity of problems can be heard, and more importantly a diversity of solutions can be designed to address issues faced by communities across the globe which in turn contribute to society’s resilience. Excluding voices from particular communities excludes the plurality of thinking when looking at an issue while also reducing our likelihood of resolving it51. Diversity is thus a ‘superpower’ that has long been overlooked. Cognitive diversity, which is shaped by factors including identity diversity (e.g., race, gender) has also been linked to better outcomes and can yield ‘bonuses’ such as improved problem-solving, innovation, and accuracy52,53. It is also important to recognise that research direction can change and become increasingly valid if larger groups of underrepresented communities are legitimately incorporated54. The ‘diversity-innovation paradox’, where underrepresented groups generate higher rates of novelty which is undervalued and does not translate into successful careers vis-a-vis majority groups, must be addressed through equitable recognition of contributions to avoid a replication of stratification in academia. Meaningful representation can challenge exclusion and advance social justice55,56.

What discussions are we missing?

While there are many ongoing conversations on how to achieve different facets of ocean equity and justice, there are important aspects that urgently need to be addressed. The first is specific to the ocean research community, the second is broadly applicable to the field of conservation, the third relates to field-based disciplines, and the last applies across many fields where experience is a necessary step for career progress.

Increasing access to the ocean

In many coastal nations particularly in the Global South and low-income communities, in-water experiences are limited due to a fear around the ocean stemming from various sources, including folklore (traditionally referring to the ocean as the devil), a lack of awareness about the ocean, the frequency of reported drownings as a result of a lack of swimming capacity or historical discrimination57,58. This lack of access, which can be increased through immersive experiences at local beaches and swim training, prevents many people from diverse backgrounds from participating in marine conservation. To address the issues of equity and justice around our oceans it is important to recognise the role of in-water opportunities combined with ocean literacy for communities that are otherwise denied them.

Pay-to-volunteer/volunteer programmes

Here, students, graduates and early-career researchers predominantly from the Global North volunteer or pay to work in conservation projects run by international not-for-profit and for-profit organisations in the Global South. They typically volunteer their time and effort for weeks to months per project with no financial compensation but often have their accommodation and subsistence costs covered by the organisation. The fundamental issue is that the pay-to-volunteer model can create opportunities for organisations to prioritise profit-making over local conservation priorities, thereby perpetuating parachute science practices59,60. Moreover, it can be exclusionary to nationals who cannot afford to work for free or pay to work59, depriving them when it comes to future career opportunities60. Furthermore, these schemes can exclude local scientists from participating when programmes only include overseas nationals.

That said, grassroots-level organisations with small working budgets to resolve large conservation challenges (particularly in the Global South) can and have benefited from the work of volunteers. This is particularly so if volunteers are skilled, can contribute meaningfully to conservation goals, work equitably with local teams and if the organisations do not depend on volunteers to sustain operations and workforce to achieve their objectives. In return, volunteers pay for these experiences over tourism because they feel they contribute to science while gaining a more interactive experience with the focal species61. We do not, therefore, argue that the pay-to-volunteer/volunteer model is inherently bad, but recognise that as the industry remains largely unregulated, there is opportunity for the exploitation of volunteers and a lack of focus on achieving conservation outcomes and impact. Further, it can also lead to the neglect of local needs, a hindering of work progress and the completion of unsatisfactory work62 (particularly due to the short-term nature of these opportunities)63. Future work could systematically assess the pay-to-volunteer model, specifically in the marine space, to provide a balanced overview of its pros and cons, to understand what factors influence the shortcomings and offer clear guidelines for best practice.

People living with disabilities

The field of geosciences, of which ocean science is a part, is the least diverse of the academic disciplines in STEM64. Past efforts to address diversity issues have focused primarily on gender or ethnicity65, but excluded those living with disabilities. One barrier to people with physical disabilities is fieldwork. This component is often considered essential for participation in ocean sciences. While there have been discussions on how to mitigate the exclusion of people with disabilities, the solutions primarily focus on marine education and land-based geoscience disciplines65,66, with few exceptions67. While ocean science presents challenges when it comes to conducting fieldwork in remote locations and/or on a vessel for extended periods, not all research necessitates this type of data collection. Collaborators could sometimes help with fieldwork, so it does not represent a barrier. To be inclusive, it is important to recognise and acknowledge that, as individuals, we all have a different and unique combination of skills and things we may find challenging. Rather than assuming what these are for others, collecting this information non-judgementally would open the way for building teams and opportunities that fit these varying abilities, skills, and experiences. It is also important to emphasise the many ways of engaging in ocean sciences which may require skill sets beyond the capacity to conduct fieldwork. However, lab techniques and equipment can also be exclusionary when, among other things, access, mobility, and dexterity are not considered. For those with mental disabilities, there are a range of different challenges. These are often magnified because a of the stigma associated with many conditions. While we are not qualified to suggest ways to mitigate the exclusion of people living with disabilities, we feel it is an important issue that should be addressed immediately.

Passion exploitation

This is the legitimisation of the exploitation of people’s passion for their work68. This exploitation which manifests largely as pro bono requests, is commonly seen in jobs fuelled by passion, such as social work and conservation. It occurs because of the false assumption that passionate workers would have volunteered if provided the opportunity and the belief that, for passionate workers, the work is itself a reward. It fails to recognise that in some cultures, professionals are already volunteering their time to level the playing field in their countries due to limited resources, and the urgency of issues leads them to support the less fortunate in their countries. Passion exploitation also minimises the value given to areas where it occurs, as appropriate resources are not assigned.

Other instances of passion exploitation include the burden of service that academics and researchers of colour shoulder to achieve diversity and inclusion in their relevant institutions. Known as the ‘cultural or minority tax’14, these services are often uncompensated, unacknowledged and unrewarded and include tasks such as sitting on DEI committees, translating documents or being ambassadors for their countries—tasks that their white counterparts are exempt from69. This tax applies to other minority groups as well70.

Conclusion

While the ocean community has taken steps over the last few years to discuss existing inequities and power imbalances publicly, many issues still need to be addressed, some of which have been identified here. While honest and transparent dialogue is the first necessary step for change, it is equally important to identify tangible actions that will enable such change. Many of these changes require a significant shift in institutional cultures and norms perpetuating discrimination, racism, and colonial approaches to ocean sciences. Such actions need to be co-identified and implemented by various stakeholders involved in ocean science, including researchers, professional societies, intergovernmental groups, institutions, funders, and publishers. It will take time and resources and, most importantly, a willingness from all parties to change the status quo. Achieving social equity will not be easy and will not happen overnight. To all, who at times despair after years of slow progress, we appreciate your allyship and we encourage you to continue to persevere in building a better and more equitable ocean research community for the benefit of our ocean, ourselves and future generations.

Data availability

All data needed to evaluate the conclusions in the paper are present in the paper.

References

Spalding, A. K. et al. Engaging the tropical majority to make ocean governance and science more equitable and effective. npj Ocean Sustain. 2, 8 (2023).

de Vos, A. The problem of ‘Colonial Science’. Sci. Am. (2020). https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/the-problem-of-colonial-science/.

Stefanoudis, P. V. et al. Turning the tide of parachute science. Curr. Biol. 31, R184–R185 (2021).

Ford, H. V. et al. The fundamental links between climate change and marine plastic pollution. Sci. Total Environ. 806, 150392 (2022).

Sumaila, U. R. & Tai, T. C. End overfishing and increase the resilience of the ocean to climate change. Front. Marine Sci. 7, 523 (2020).

Bennett, N. J. et al. Advancing social equity in and through marine conservation. Front. Marine Sci. 8, 71153 (2021).

Maguire, R., Carter, G. & Mangubhai, S. Gender and the Glasgow COP:” Please do more”. (2022).

Pai, M. Passport And Visa Privileges In Global Health. Forbes (2022). <https://www.forbes.com/sites/madhukarpai/2022/06/06/passport-and-visa-privileges-in-global-health/?sh=57a88b5d4272>.

IOC-UNESCO. Co-designing the science we need for the ocean we want: guidance and recommendations for collaborative approaches to designing & implementing Decade actions. The Ocean Decade Series 29 (2021).

Rudd, L. F. et al. Overcoming racism in the twin spheres of conservation science and practice. Proc. R. Soc. B 288, 20211871 (2021).

Davies, S. W. et al. Promoting inclusive metrics of success and impact to dismantle a discriminatory reward system in science. PLoS Biol. 19, e3001282 (2021).

Cronin, M. R. et al. Anti-racist interventions to transform ecology, evolution and conservation biology departments. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 5, 1213–1223 (2021).

Trisos, C. H., Auerbach, J. & Katti, M. Decoloniality and anti-oppressive practices for a more ethical ecology. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 5, 1205–1212 (2021).

Faucett, E. A., Brenner, M. J., Thompson, D. M. & Flanary, V. A. Tackling the minority tax: a roadmap to redistributing engagement in diversity, equity, and inclusion initiatives. Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery 166, 1174–1181 (2022).

Shellock, R. J. et al. Breaking down barriers: The identification of actions to promote gender equality in interdisciplinary marine research institutions. One Earth 5, 687–708 (2022).

Gaskins, L. C. & McClain, C. R. Visible name changes promote inequity for transgender researchers. PLoS Biol. 19, e3001104 (2021).

Lieurance, D., Kuebbing, S., McCary, M. A. & Nuñez, M. A. Words matter: how to increase gender and LGBTQIA+ inclusivity at Biological Invasions. Biol. Invasions 24, 341–344 (2022).

Arico, S. et al. Global ocean science report 2020-charting capacity for ocean sustainability. (UNESCO, 2020).

Amon, D. J., Filander, Z., Harris, L. & Harden-Davies, H. Safe working environments are key to improving inclusion in open-ocean, deep-ocean, and high-seas science. Mar. Policy 137 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpol.2021.104947.

Ahmadia, G. N. et al. Limited Progress in Improving Gender and Geographic Representation in Coral Reef Science. Front. Marine Sci. 8, 731037 (2021).

Maas, B. et al. Women and Global South strikingly underrepresented among top-publishing ecologists. Conserv. Lett. 14, e12797 (2021).

Women in Ocean Science. Sexual Harassment in Marine Science. Women in Ocean Science CIC, 16 pp. (2021). https://www.womeninoceanscience.com/sexual-harassment.

Legg, S., Wang, C., Kappel, E. & Thompson, L. Gender equity in oceanography. Annu. Rev. Marine Sci. 15, 15–39 (2023).

Nash, M. et al. “Antarctica just has this hero factor…”: Gendered barriers to Australian Antarctic research and remote fieldwork. Plos One 14, e0209983 (2019).

Hind, E. J. et al. Fostering effective international collaboration for marine science in small island states. Front. Marine Sci. 2 (2015). https://doi.org/10.3389/fmars.2015.00086.

Woodall, L. C. et al. Co-development, co-production and co-dissemination of scientific research: a case study to demonstrate mutual benefits. Biol. Lett. 17, 20200699 (2021).

Rayadin, Y. & Buřivalová, Z. What does it take to have a mutually beneficial research collaboration across countries?. Conserv. Sci. Pract. 4, e528 (2021).

Katerere, D. R., Applequist, W., Aboyade, O. M. & Togo, C. Traditional and indigenous knowledge for the modern era: a natural and applied science perspective. (CRC Press, 2019).

von der Porten, S., Ota, Y., Cisneros-Montemayor, A. & Pictou, S. The Role of Indigenous Resurgence in Marine Conservation. Coastal Manag. 47, 527–547 (2019).

Singeo, A. & Ferguson, C. E. Lessons from Palau to end parachute science in international conservation research. 37, e13971 (2022).

de Vos, A. Stowing parachutes, strengthening science. Conserv. Sci. Pract. 4, e12709 (2022).

Amano, T. et al. Tapping into non-English-language science for the conservation of global biodiversity. PLoS Biol. 19, e3001296 (2021).

Konno, K. et al. Ignoring non‐English‐language studies may bias ecological meta‐analyses. Ecol. Evol. 10, 6373–6384 (2020).

Steigerwald, E. et al. Overcoming language barriers in academia: machine translation tools and a vision for a multilingual future. Bioscience 72, 988–998 (2022).

Bertolero, M. A. et al. Racial and ethnic imbalance in neuroscience reference lists and intersections with gender. BioRxiv (2020).

Cooke, S. J. et al. Contemporary authorship guidelines fail to recognize diverse contributions in conservation science research. Ecol. Solut. Evid. 2, 1–7 (2021).

Liboiron, M. et al. Equity in author order: a feminist laboratory’s approach. Catalyst: Feminism, Theory, Technoscience 3, 1–17 (2017).

DOSI. Open Access Publishing Considerations for the Deep-Ocean Science Community. Deep Ocean Stewardship Initiative Policy Brief (2022). <https://www.dosi-project.org/uploads/open-access-deep-community-briefing.pdf>.

Piwowar, H. et al. The state of OA: a large-scale analysis of the prevalence and impact of Open Access articles. Peerj 6, e4375 (2018).

Dawson, M. N. Our debt to peer reviewers, 2022. J. Biogeogr. 50, 450–451 (2023).

Williams, J. W. et al. Shifts to open access with high article processing charges hinder research equity and careers. J. Biogeogr, 1–5 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1111/jbi.14697.

Borrego, Á. Article processing charges for open access journal publishing: A review.Learned Publishing 36, 359–378 (2023).

Gomez, C. J., Herman, A. C. & Parigi, P. Leading countries in global science increasingly receive more citations than other countries doing similar research. Nat. Hum. Behav. 6, 919–929 (2022).

Harden-Davies, H. et al. Capacity development in the Ocean Decade and beyond: Key questions about meanings, motivations, pathways, and measurements. Earth System Governance 12 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esg.2022.100138.

Harden-Davies, H. & Snelgrove, P. Science collaboration for capacity building: advancing technology transfer through a treaty for biodiversity beyond national jurisdiction. Front. Marine Sci. 7, 40 (2020).

Costa, C., Fanelli, E., Marini, S., Danovaro, R. & Aguzzi, J. Global deep-sea biodiversity research trends highlighted by science mapping approach. Front. Marine Sci. 7, 384 (2020).

Bell, K. L. et al. Low-Cost, Deep-Sea Imaging and Analysis Tools for Deep-Sea Exploration: A Collaborative Design Study. Front. Marine Sci. 9, 873700 (2022).

Niner, H. J. & Wassermann, S. N. Better for whom? Leveling the injustices of international conferences by moving online. Front. Marine Sci. 8, 638025 (2021).

Stefanoudis, P. V. et al. Moving conferences online: lessons learned from an international virtual meeting. Proc. R. Soc. B 288, 20211769 (2021).

Puccinelli, E. et al. Hybrid conferences: opportunities, challenges and ways forward. Front. Marine Sci. 9, 902772 (2022).

Belhabib, D. Ocean science and advocacy work better when decolonized. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 5, 709–710 (2021).

Bendor, J. & Page, S. E. Optimal team composition for tool‐based problem solving. J. Econ. Manag. Strateg. 28, 734–764 (2019).

Page, S. E. The diversity bonus: How great teams pay off in the knowledge economy. (Princeton University Press, 2019).

Hong, L. & Page, S. The contributions of diversity, accuracy, and group size on collective accuracy. Accuracy, and Group Size on Collective Accuracy (October 15, 2020) (2020).

Hofstra, B. et al. The diversity–innovation paradox in science. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. 117, 9284–9291 (2020).

Saunders, F. et al. Theorizing social sustainability and justice in marine spatial planning: Democracy, diversity, and equity. Sustainability 12, 2560 (2020).

Wiltse, J. Contested waters: A social history of swimming pools in America. (Univ of North Carolina Press, 2007).

World Health Organization. Global drowning report: preventing a leading killer. Switzerland: Zurich (2014).

Vercammen, A., Park, C., Goddard, R., Lyons-White, J. & Knight, A. A reflection on the fair use of unpaid work in conservation. Conserv. Soc. 18, 399–404 (2020).

Osiecka, A. N., Quer, S., Wróbel, A. & Osiecka-Brzeska, K. Unpaid work in marine science: a snapshot of the early-career job market. Front. Marine Sci. 8, 690163 (2021).

Campbell, L. M. & Smith, C. What makes them pay? Values of volunteer tourists working for sea turtle conservation. Environ. Manag. 38, 84–98 (2006).

Guttentag, D. A. The possible negative impacts of volunteer tourism. Int. J. Tour. Res. 11, 537–551 (2009).

Ocañas, A. R. & Thomsen, J. M. Challenges and opportunities of voluntourism conservation projects in Peru’s Madre de Dios region. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 45, 101046 (2023).

George, Y. S., Neale, D. S., Van Horne, V. & Malcom, S. M. In pursuit of a diverse science, technology, engineering, and mathematics workforce: recommended research priorities to enhance participation by underrepresented minorities. American Association for the Advancement of Science and NSF Directorate for Education and Human Resources Programs, pp. 32 (2021).

Stokes, A., Feig, A. D., Atchison, C. L. & Gilley, B. Making geoscience fieldwork inclusive and accessible for students with disabilities. Geosphere 15, 1809–1825 (2019).

Atchison, C. L., Marshall, A. M. & Collins, T. D. A multiple case study of inclusive learning communities enabling active participation in geoscience field courses for students with physical disabilities. J. Geosci. Educ. 67, 472–486 (2019).

Fraser, K. Oceanography for the visually impaired. Sci. Teach. 75, 28 (2008).

Kim, J. Y., Campbell, T. H., Shepherd, S. & Kay, A. C. in Academy of Management Proceedings. 14712 (Academy of Management Briarcliff Manor, NY 10510).

Akin, Y. The time tax put on scientists of colour. Nature 583, 479–481 (2020).

Wijesingha, R. & Ramos, H. Human capital or cultural taxation: What accounts for differences in tenure and promotion of racialized and female faculty? Can. J. High. Educ. 47, 54–75 (2017).

Van Stavel, J. et al. In OCEANS 2021: San Diego–Porto. 1–6 (IEEE).

Miriti, M. N., Bailey, K., Halsey, S. J. & Harris, N. C. Hidden figures in ecology and evolution. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 4, 1282–1282 (2020).

Ocampo-Ariza, C. et al. Global South leadership towards inclusive tropical ecology and conservation. Perspect. Ecol. Conserv. 21, 17–24 (2023).

Rowson, B., et al. Vol. 49, 947–949 (Springer, 2021).

Harden-Davies, H. et al. How can a new UN ocean treaty change the course of capacity building? Aquat. Conserv. Mar. Freshw. Ecosy. 32, 907–91 (2022).

Amon, D. J. et al. My Deep Sea, My Backyard: a pilot study to build capacity for global deep-ocean exploration and research. Philos. Transac. R. Soc. B 377, 20210121 (2022).

Bell, K. L. C. et al. Global summary. In K. L. C. Bell, M. C. Quinzin, S. Poulton, A. Hope, & D. Amon (Eds.), Global Deep-Sea Capacity Assessment. Ocean Discovery League, Saunderstown, USA (2022). https://doi.org/10.21428/cbd17b20.e8104259.

Acknowledgements

This is Nekton Contribution No. 34. A.d.V. is funded by the Schmidt Foundation. We wish to thank the two anonymous reviewers whose insightful comments have enhanced the content of this paper.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

P.V.S. conceived the idea of the review. All authors contributed to the study design and data collection. A.d.V. and P.V.S. led the original draft, including tables and figures, with comments, edits, and revisions from S.C.S., S.M., L.N., and L.C.W.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

de Vos, A., Cambronero-Solano, S., Mangubhai, S. et al. Towards equity and justice in ocean sciences. npj Ocean Sustain 2, 25 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s44183-023-00028-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s44183-023-00028-4