Abstract

We provide a brief review of human mobility science and present three key areas where we expect to see substantial advancements. We start from the mind and discuss the need to better understand how spatial cognition shapes mobility patterns. We then move to societies and argue the importance of better understanding new forms of transportation. We conclude by discussing how algorithms shape mobility behavior and provide useful tools for modelers. Finally, we discuss how progress on these research directions may help us address some of the challenges our society faces today.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

$29.99 / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 digital issues and online access to articles

$99.00 per year

only $8.25 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Ravenstein, E. G. The laws of migration. J. R. Stat. Soc. 52, 241–305 (1889).

Ravenstein, E. G. The Birthplaces of the People and the Laws of Migration (Trübner, 1876).

Barbosa, H. et al. Human mobility: models and applications. Phys. Rep. 734, 1–74 (2018).

Wang, J., Kong, X., Xia, F. & Sun, L. Urban human mobility: data-driven modeling and prediction. SIGKDD Explor. Newsl. 21, 1–19 (2019).

O’Dea, S. Smartphone users worldwide 2021 statista. Statista www.statista.com/statistics/330695/number-of-smartphone-users-worldwide/ (2022).

Alessandretti, L., Aslak, U. & Lehmann, S. The scales of human mobility. Nature 587, 402–407 (2020).

Barbosa, H., de Lima-Neto, F. B., Evsukoff, A. & Menezes, R. The effect of recency to human mobility. EPJ Data Sci. 4, 1–14 (2015).

Bongiorno, C. et al. Vector-based pedestrian navigation in cities. Nat. Comput. Sci. 1, 678–685 (2021).

Cornacchia, G. & Pappalardo, L. A mechanistic data-driven approach to synthesize human mobility considering the spatial, temporal, and social dimensions together. ISPRS Int. J. GeoInf. 10, 599 (2021).

Pappalardo, L. et al. Returners and explorers dichotomy in human mobility. Nat. Commun. 6, 8166 (2015).

Schläpfer, M. et al. The universal visitation law of human mobility. Nature 593, 522–527 (2021).

Alessandretti, L., Sapiezynski, P., Lehmann, S. & Baronchelli, A. Multi-scale spatio-temporal analysis of human mobility. PLoS ONE 12, 0171686 (2017).

Kraemer, M. U. et al. Mapping global variation in human mobility. Nat. Hum. Behav. 4, 800–810 (2020).

Noulas, A., Scellato, S., Lambiotte, R., Pontil, M. & Mascolo, C. A tale of many cities: universal patterns in human urban mobility. PLoS ONE 7, 37027 (2012).

Burbey, I. & Martin, T. L. A survey on predicting personal mobility. Int. J. Pervasive Comput. Commun. 8, 5–22 (2012).

Calabrese, F., Di Lorenzo, G. & Ratti, C. Human mobility prediction based on individual and collective geographical preferences. In 13th International Conference on Intelligent Transportation Systems 312–317 (IEEE, 2010).

Dai, J., Yang, B., Guo, C. & Ding, Z. Personalized route recommendation using big trajectory data. In 31st International Conference on Data Engineering 543–554 (IEEE, 2015).

Luca, M., Barlacchi, G., Lepri, B. & Pappalardo, L. A survey on deep learning for human mobility. ACM Comput. Surv. 55, 1–44 (2021).

Pappalardo, L. & Simini, F. Data-driven generation of spatio-temporal routines in human mobility. Data Min. Knowl. Discov. 32, 787–829 (2018).

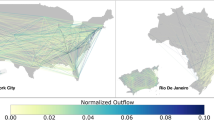

Simini, F., Barlacchi, G., Luca, M. & Pappalardo, L. A deep gravity model for mobility flows generation. Nat. Commun. 12, 6576 (2021).

Zheng, Y. Trajectory data mining: an overview. ACM Trans. Intell. Syst. Technol. 6, 1–41 (2015).

Zheng, Y., Capra, L., Wolfson, O. & Yang, H. Urban computing: concepts, methodologies, and applications. ACM Trans. Intell. Syst. Technol. 5, 1–55 (2014).

Pappalardo, L., Ferres, L., Sacasa, M., Cattuto, C. & Bravo, L. Evaluation of home detection algorithms on mobile phone data using individual-level ground truth. EPJ Data Sci. 10, 29 (2021).

Fudolig, M. I. D., Monsivais, D., Bhattacharya, K., Jo, H.-H. & Kaski, K. Internal migration and mobile communication patterns among pairs with strong ties. EPJ Data Sci. 10, 16 (2021).

Moro, E., Calacci, D., Dong, X. & Pentland, A. Mobility patterns are associated with experienced income segregation in large US cities. Nat. Commun. 12, 4633 (2021).

Pappalardo, L. et al. An analytical framework to nowcast well-being using mobile phone data. Int. J. Data Sci. Anal. 2, 75–92 (2016).

Xue, H., Voutharoja, B. P. & Salim, F. D. Leveraging language foundation models for human mobility forecasting. In Proc. 30th International Conference on Advances in Geographic Information Systems Vol. 90, 1–9 (ACM, 2022).

Aleta, A. et al. Quantifying the importance and location of SARS-CoV-2 transmission events in large metropolitan areas. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 119, 2112182119 (2022).

Lucchini, L. et al. Living in a pandemic: changes in mobility routines, social activity and adherence to COVID-19 protective measures. Sci. Rep. 11, 24452 (2021).

Borst, H. C. et al. Influence of environmental street characteristics on walking route choice of elderly people. J. Environ. Psychol. 29, 477–484 (2009).

Coutrot, A. et al. Entropy of city street networks linked to future spatial navigation ability. Nature 604, 104–110 (2022).

Gauvin, L. et al. Gender gaps in urban mobility. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 7, 11 (2020).

Macedo, M., Lotero, L., Cardillo, A., Menezes, R. & Barbosa, H. Differences in the spatial landscape of urban mobility: gender and socioeconomic perspectives. PLoS ONE 17, 0260874 (2022).

Barbosa, H. et al. Uncovering the socioeconomic facets of human mobility. Sci. Rep. 11, 8616 (2021).

Gonzalez, M. C., Hidalgo, C. A. & Barabasi, A.-L. Understanding individual human mobility patterns. Nature 453, 779–782 (2008).

Gallotti, R., Bazzani, A., Rambaldi, S. & Barthelemy, M. A stochastic model of randomly accelerated walkers for human mobility. Nat. Commun. 7, 12600 (2016).

Pappalardo, L., Rinzivillo, S., Qu, Z., Pedreschi, D. & Giannotti, F. Understanding the patterns of car travel. Eur. Phys. J. Spec. Top. 215, 61–73 (2013).

Song, C., Qu, Z., Blumm, N. & Barabási, A.-L. Limits of predictability in human mobility. Science 327, 1018–1021 (2010).

Scherrer, L., Tomko, M., Ranacher, P. & Weibel, R. Travelers or locals? Identifying meaningful sub-populations from human movement data in the absence of ground truth. EPJ Data Sci. 7, 1–21 (2018).

Alessandretti, L., Sapiezynski, P., Sekara, V., Lehmann, S. & Baronchelli, A. Evidence for a conserved quantity in human mobility. Nat. Hum. Behav. 2, 485–491 (2018).

Barbosa, H., de Lima-Neto, F. B., Evsukoff, A. & Menezes, R. The effect of recency to human mobility. EPJ Data Sci. 4, 1–14 (2015).

Song, C., Koren, T., Wang, P. & Barabási, A.-L. Modelling the scaling properties of human mobility. Nat. Phys. 6, 818–823 (2010).

Lu, X., Wetter, E., Bharti, N., Tatem, A. J. & Bengtsson, L. Approaching the limit of predictability in human mobility. Sci. Rep. 3, 2923 (2013).

Smith, G., Wieser, R., Goulding, J. & Barrack, D. A refined limit on the predictability of human mobility. In International Conference on Pervasive Computing and Communications 88–94 (IEEE, 2014).

Cuttone, A., Lehmann, S. & González, M. C. Understanding predictability and exploration in human mobility. EPJ Data Sci. 7, 1–17 (2018).

Ikanovic, E. L. & Mollgaard, A. An alternative approach to the limits of predictability in human mobility. EPJ Data Sci. 6, 1–10 (2017).

Schneider, C. M., Belik, V., Couronné, T., Smoreda, Z. & González, M. C. Unravelling daily human mobility motifs. J. R. Soc. Interface 10, 20130246 (2013).

Yan, X.-Y., Wang, W.-X., Gao, Z.-Y. & Lai, Y.-C. Universal model of individual and population mobility on diverse spatial scales. Nat. Commun. 8, 1639 (2017).

Simini, F., González, M. C., Maritan, A. & Barabási, A.-L. A universal model for mobility and migration patterns. Nature 484, 96–100 (2012).

Tversky, B. Cognitive maps, cognitive collages, and spatial mental models. In European Conference on Spatial Information Theory 14–24 (Springer, 1993).

Sadalla, E. K., Burroughs, J. W. & Staplin, L. J. Reference points in spatial cognition. J. Exp. Psychol. Hum. Learn. Mem. 6, 516–528 (1980).

Weisberg, S. M. & Newcombe, N. S. How do (some) people make a cognitive map? Routes, places, and working memory. J. Exp. Psychol. Learn. Mem. Cogn. 42, 768 (2016).

Newcombe, N. & Liben, L. S. Barrier effects in the cognitive maps of children and adults. J. Exp. Child Psychol. 34, 46–58 (1982).

Moser, E. I., Kropff, E. & Moser, M.-B. et al. Place cells, grid cells, and the brain’s spatial representation system. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 31, 69–89 (2008).

Hirtle, S. C. & Jonides, J. Evidence of hierarchies in cognitive maps. Mem. Cogn. 13, 208–217 (1985).

Balaguer, J., Spiers, H., Hassabis, D. & Summerfield, C. Neural mechanisms of hierarchical planning in a virtual subway network. Neuron 90, 893–903 (2016).

Lynch, K. The Image of the City Vol. 1 (MIT Press, 1960).

Filomena, G., Verstegen, J. A. & Manley, E. A computational approach to ‘The Image of the City’. Cities 89, 14–25 (2019).

Winter, S., Tomko, M., Elias, B. & Sester, M. Landmark hierarchies in context. Environ. Plann. B 35, 381–398 (2008).

Kuipers, B. Modeling spatial knowledge. Cogn. Sci. 2, 129–153 (1978).

Chown, E., Kaplan, S. & Kortenkamp, D. Prototypes, location, and associative networks (PLAN): towards a unified theory of cognitive mapping. Cogn. Sci. 19, 1–51 (1995).

Manley, E., Filomena, G. & Mavros, P. A spatial model of cognitive distance in cities. Int. J. Geogr. Inf. Sci. 35, 2316–2338 (2021).

Ben-Akiva, M., Bergman, M., Daly, A. J. & Ramaswamy, R. Modelling inter urban route choice behaviour. In Papers Presented During the Ninth International Symposium on Transportation and Traffic Theory 299–330 (VNU Science Press, 1984).

Manley, E. J., Addison, J. D. & Cheng, T. Shortest path or anchor-based route choice: a large-scale empirical analysis of minicab routing in London. J. Transp. Geogr. 43, 123–139 (2015).

Malleson, N. et al. The characteristics of asymmetric pedestrian behavior: a preliminary study using passive smartphone location data. Trans. GIS 22, 616–634 (2018).

Lima, A., Stanojevic, R., Papagiannaki, D., Rodriguez, P. & González, M. C. Understanding individual routing behaviour. J. R. Soc. Interface 13, 20160021 (2016).

Sevtsuk, A. & Basu, R. The role of turns in pedestrian route choice: a clarification. J. Transp. Geogr. 102, 103392 (2022).

Miranda, A. S., Fan, Z., Duarte, F. & Ratti, C. Desirable streets: using deviations in pedestrian trajectories to measure the value of the built environment. Comput. Environ. Urban Syst. 86, 101563 (2021).

Guo, Z. & Loo, B. P. Pedestrian environment and route choice: evidence from New York City And Hong Kong. J. Transp. Geogr. 28, 124–136 (2013).

Gilbert, N. et al. (eds) Tools and Techniques for Social Science Simulation 83–114 (Springer, 2000).

Georgeff, M., Pell, B., Pollack, M., Tambe, M. & Wooldridge, M. The belief-desire-intention model of agency. In Proc. Intelligent Agents V: Agents Theories, Architectures, and Languages: 5th International Workshop 1–10 (Springer, 1999).

Manley, E., Orr, S. W. & Cheng, T. A heuristic model of bounded route choice in urban areas. Transp. Res. Part C 56, 195–209 (2015).

Aboutaleb, Y. M., Danaf, M., Xie, Y. & Ben-Akiva, M. Discrete choice analysis with machine learning capabilities. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/2101.10261 (2021).

Banino, A. et al. Vector-based navigation using grid-like representations in artificial agents. Nature 557, 429–433 (2018).

Mirowski, P. et al. Learning to navigate in cities without a map. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems Vol. 31, 2424–2435 (Curran Associates, 2018).

Hancock, T. O. & Choudhury, C. F. Utilising physiological data for augmenting travel choice models: methodological frameworks and directions of future research. Transp. Rev. https://doi.org/10.1080/01441647.2023.2175274 (2023).

Qin, T., Dong, W. & Huang, H. Perceptions of space and time of public transport travel associated with human brain activities: a case study of bus travel in Beijing. Comput. Environ. Urban Syst. 99, 101919 (2023).

Coutrot, A. et al. Global determinants of navigation ability. Curr. Biol. 28, 2861–28664 (2018).

Montello, D. R. in Spatial and Temporal Reasoning in Geographic Information Systems 143–154 (Oxford Univ. Press, 1998).

Mavros, P. et al. Collaborative wayfinding under distributed spatial knowledge. In 15th International Conference on Spatial Information Theory: Leibniz International Proceedings in Informatics Vol. 240 (eds Ishikawa, T. et al.) 25:1–25:10 (Schloss Dagstuhl, Leibniz-Zentrum für Informatik, 2022).

Spiers, H. J. & Maguire, E. A. The dynamic nature of cognition during wayfinding. J. Environ. Psychol. 28, 232–249 (2008).

Ishikawa, T., Fujiwara, H., Imai, O. & Okabe, A. Wayfinding with a GPS-based mobile navigation system: a comparison with maps and direct experience. J. Environ. Psychol. 28, 74–82 (2008).

Gardony, A. L., Brunyé, T. T., Mahoney, C. R. & Taylor, H. A. How navigational aids impair spatial memory: evidence for divided attention. Spat. Cogn. Comput. 13, 319–350 (2013).

Alessandretti, L., Natera Orozco, L. G., Battiston, F., Saberi, M. & Szell, M. Multimodal urban mobility and multilayer transport networks. Environ. Plann. B. https://doi.org/10.1177/23998083221108190 (2022).

Mohamed, K., Côme, E., Oukhellou, L. & Verleysen, M. Clustering smart card data for urban mobility analysis. IEEE Trans. Intell.Transp. Syst. 18, 712–728 (2016).

Zhong, C., Manley, E., Arisona, S. M., Batty, M. & Schmitt, G. Measuring variability of mobility patterns from multiday smart-card data. J. Comput. Sci. 9, 125–130 (2015).

Zhong, C. et al. Variability in regularity: mining temporal mobility patterns in London, Singapore and Beijing using smart-card data. PLoS ONE 11, 0149222 (2016).

Nations, U. World Urbanization Prospects (United Nations, 2014)

Pelaez Bueno, A. Identifying and Quantifying Mobility Hubs MSc thesis. ETH Zurich (2021).

Wirtz, M. H. & Klähr, J. Smartphone based in/out ticketing systems: a new generation of ticketing in public transport and its performance testing. WIT Trans. Built Environ. 182, 351–359 (2019).

Baldauf, M. & Tomitsch, M. Pervasive displays for public transport: an overview of ubiquitous interactive passenger services. In Proc. 9th ACM International Symposium on Pervasive Displays 37–45 (Association for Computing Machinery, 2020).

Nahmias-Biran, B.-h et al. Enriching activity-based models using smartphone-based travel surveys. Transp. Res. Rec. 2672, 280–291 (2018).

Amini, A., Kung, K., Kang, C., Sobolevsky, S. & Ratti, C. The impact of social segregation on human mobility in developing and industrialized regions. EPJ Data Sci. 3, 1–20 (2014).

Crawford, F. W. et al. Impact of close interpersonal contact on COVID-19 incidence: evidence from 1 year of mobile device data. Sci. Adv. 8, 5499 (2022).

Machado, C. A. S., de Salles Hue, N. P. M., Berssaneti, F. T. & Quintanilha, J. A. An overview of shared mobility. Sustainability 10, 4342 (2018).

McNally, M. G. in Handbook of Transport Modelling (Emerald Group, 2007).

Axhausen, K. W., Horni, A. & Nagel, K. The Multi-agent Transport Simulation MATSim (Ubiquity Press, 2016).

Lu, N., Cheng, N., Zhang, N., Shen, X. & Mark, J. W. Connected vehicles: solutions and challenges. IEEE Internet Things J. 1, 289–299 (2014).

Ward, J. A., Evans, A. J. & Malleson, N. S. Dynamic calibration of agent-based models using data assimilation. R. Soc. Open Sci. 3, 150703 (2016).

Morandi, V. Bridging the user equilibrium and the system optimum in static traffic assignment: a review. 4OR https://doi.org/10.1007/s10288-023-00540-w (2023).

Sejnowski, T. J. The Deep Learning Revolution (MIT Press, 2018).

LeCun, Y., Bengio, Y. & Hinton, G. Deep learning. Nature 521, 436–444 (2015).

Silver, D. et al. Mastering the game of Go with deep neural networks and tree search. Nature 529, 484–489 (2016).

Titano, J. J. et al. Automated deep-neural-network surveillance of cranial images for acute neurologic events. Nat. Med. 24, 1337–1341 (2018).

Krizhevsky, A., Sutskever, I. & Hinton, G. E. ImageNet classification with deep convolutional neural networks. Commun. ACM 60, 84–90 (2017).

Wu, Y. et al. Google’s neural machine translation system: bridging the gap between human and machine translation. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/1609.08144 (2016).

Zheng, X., Han, J. & Sun, A. A survey of location prediction on Twitter. IEEE Trans. Knowl. Data Eng. 30, 1652–1671 (2018).

Rumbert, D. E. Learning internal representations by error propagation. Parallel Distrib. Process. 1, 318–363 (1986).

Jiang, S. et al. The TimeGeo modeling framework for urban mobility without travel surveys. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 113, 5370–5378 (2016).

Toole, J. L., Herrera-Yaqüe, C., Schneider, C. M. & González, M. C. Coupling human mobility and social ties. J. R. Soc. Interface 12, 20141128 (2015).

Zipf, G. K. The P1P2/D hypothesis: on the intercity movement of persons. Am. Sociol. Rev. 11, 677–686 (1946).

Liu, E.-J. & Yan, X.-Y. A universal opportunity model for human mobility. Sci. Rep. 10, 4657 (2020).

Goodfellow, I. et al. Generative adversarial nets. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 27 (NIPS, 2014)

Kingma, D. P. & Welling, M. Auto-encoding variational Bayes. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/1312.6114 (2013).

Mauro, G., Luca, M., Longa, A., Lepri, B. & Pappalardo, L. Generating mobility networks with generative adversarial networks. EPJ Data Sci. 11, 58 (2022).

Bao, H., Zhou, X., Xie, Y., Zhang, Y. & Li, Y. COVID-GAN+: estimating human mobility responses to COVID-19 through spatio-temporal generative adversarial networks with enhanced features. ACM Trans. Intell. Syst. Technol. https://doi.org/10.1145/3481617 (2022).

Feng, J. et al. Learning to simulate human mobility. In Proc. 26th ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining 3426–3433 (ACM, 2020)

Huang, D. et al. A variational autoencoder based generative model of urban human mobility. In Conference on Multimedia Information Processing and Retrieval 425–430 (IEEE, 2019).

Ouyang, K., Shokri, R., Rosenblum, D. S. & Yang, W. A non-parametric generative model for human trajectories. In Proc. Twenty-Seventh International Joint Conference on Artificial Intelligence Vol. 18, 3812–3817 (AAAI, 2018).

Amatriain, X. Transformer models: an introduction and catalog. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/2302.07730 (2023).

Mizuno, T., Fujimoto, S. & Ishikawa, A. Generation of individual daily trajectories by GPT-2. Front. Phys. 10, 1118 (2022).

Ma, J. et al. Human trajectory completion with transformers. In International Conference on Communications 3346–3351 (IEEE, 2022).

Guidotti, R. et al. A survey of methods for explaining black box models. ACM Comput. Surv. 51, 1–42 (2018).

Naretto, F., Pellungrini, R., Monreale, A., Nardini, F. M. & Musolesi, M. in Discovery Science. DS 2020. Lecture Notes in Computer Science Vol. 12323 (eds Appice, A. et al.) 403–418 (Springer, 2020).

Huang, X. & Marques-Silva, J. The inadequacy of shapley values for explainability. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/2302.08160 (2023).

Kumar, I. E., Venkatasubramanian, S., Scheidegger, C. & Friedler, S. Problems with shapley-value-based explanations as feature importance measures. In International Conference on Machine Learning 5491–5500 (PMLR. 2020).

Jonietz, D. et al. Urban mobility analytics: report from Dagstuhl seminar 22162. Dagstuhl Rep. 12, 26–53 (2022).

Rolnick, D. et al. Tackling climate change with machine learning. ACM Comput. Surv. 55, 1–96 (2022).

Bai, X. et al. Six research priorities for cities and climate change. Nature 555, 23–25 (2018).

Voukelatou, V. et al. Measuring objective and subjective well-being: dimensions and data sources. Int. J. Data Sci. Anal. 11, 279–309 (2021).

Yan, A. & Howe, B. Fairness-aware demand prediction for new mobility. In Proc. AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence Vol. 34, 1079–1087 (AAAI, 2020).

Yan, A. & Howe, B. FairST: equitable spatial and temporal demand prediction for new mobility systems. In Proc. 27th International Conference on Advances in Geographic Information Systems 552–555 (ACM, 2019).

Yan, A. & Howe, B. Fairness in practice: a survey on equity in urban mobility. Q. Bull. Comput. Soc. IEEE 42, 49–63 (2019).

Ngo, N. S., Götschi, T. & Clark, B. Y. The effects of ride-hailing services on bus ridership in a medium-sized urban area using micro-level data: evidence from the Lane Transit District. Transp. Policy 105, 44–53 (2021).

Ge, Y., Knittel, C. R., MacKenzie, D. & Zoepf, S. Racial and Gender Discrimination in Transportation Network Companies Technical Report (National Bureau of Economic Research, 2016).

Arora, N. et al. Quantifying the sustainability impact of Google Maps: a case study of Salt Lake City. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/2111.03426 (2021).

Perez-Prada, F., Monzon, A. & Valdes, C. Managing traffic flows for cleaner cities: the role of green navigation systems. Energies 10, 791 (2017).

Mehrvarz, N., Ye, Z., Barati, K. & Shen, X. Optimal Travel Routes of On-road Vehicles Considering Sustainability (IAARC Publications, 2020).

Cornacchia, G. et al. How routing strategies impact urban emissions. In Proc. 30th International Conference on Advances in Geographic Information Systems https://doi.org/10.1145/3557915.3560977 (ACM, 2022).

Lai, S. et al. Effect of non-pharmaceutical interventions to contain COVID-19 in China. Nature 585, 410–413 (2020).

Haushofer, J. & Metcalf, C. J. E. Which interventions work best in a pandemic? Science 368, 1063–1065 (2020).

Gao, S. et al. Mobile phone location data reveal the effect and geographic variation of social distancing on the spread of the COVID-19 epidemic. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/2004.11430 (2020).

Chinazzi, M. et al. The effect of travel restrictions on the spread of the 2019 novel coronavirus (COVID-19) outbreak. Science 368, 395–400 (2020).

Gatto, M. et al. Spread and dynamics of the COVID-19 epidemic in Italy: effects of emergency containment measures. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 117, 10484–10491 (2020).

Jia, J. S. et al. Population flow drives spatio-temporal distribution of COVID-19 in China. Nature 582, 389–394 (2020).

Tian, H. et al. An investigation of transmission control measures during the first 50 days of the COVID-19 epidemic in China. Science 368, 638–642 (2020).

Ross, S., Breckenridge, G., Zhuang, M. & Manley, E. Household visitation during the COVID-19 pandemic. Sci. Rep. 11, 22871 (2021).

Pappalardo, L., Cornacchia, G., Navarro, V., Bravo, L. & Ferres, L. A dataset to assess mobility changes in Chile following local quarantines. Sci. Data 10, 6 (2023).

Ritchie, H. Sector by sector: where do global greenhouse gas emissions come from? Our World in Data https://ourworldindata.org/ghg-emissions-by-sector (2020).

Transforming Our World: the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development Technical Report (United Nations General Assembly, 2015).

Böhm, M., Nanni, M. & Pappalardo, L. Gross polluters and vehicle emissions reduction. Nat. Sustain. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41893-022-00903-x (2022).

Nyhan, M. et al. Predicting vehicular emissions in high spatial resolution using pervasively measured transportation data and microscopic emissions model. Atmos. Environ. 140, 352–363 (2016).

Macfarlane, J. When apps rule the road: the proliferation of navigation apps is causing traffic chaos. It’s time to restore order. IEEE Spectrum 56, 22–27 (2019).

Lu, Y., Nakicenovic, N., Visbeck, M. & Stevance, A.-S. Policy: Five priorities for the unsustainable development goals. Nature 520, 432–433 (2015).

Glaeser, E. L., Resseger, M. & Tobio, K. Inequality in cities. J. Reg. Sci. 49, 617–646 (2009).

Sanchez, T. W., Stolz, R. & Ma, J. S. Inequitable effects of transportation policies on minorities. Transp. Res. Rec. 1885, 104–110 (2004).

Smith, D. A. & Barros, J. in Urban Form and Accessibility (Mulley, C. & Nelson, J. D.) 27–44 (Elsevier, 2021).

Carpio-Pinedo, J. Multimodal transport and potential encounters with social difference: a novel approach based on network analysis. J. Urban Aff. 43, 93–116 (2021).

Gillies, S. et al. Shapely: manipulation and analysis of geometric objects. GitHub https://github.com/Toblerity/Shapely (2007).

Sekara, V. et al. in Guide to Mobile Data Analytics in Refugee Scenarios 53–66 (2019).

Schlosser, F., Sekara, V., Brockmann, D. & Garcia-Herranz, M. Biases in human mobility data impact epidemic modeling. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/2112.12521 (2021).

Zhao, Z. et al. Understanding the bias of call detail records in human mobility research. Int. J. Geogr. Inf. Sci. 30, 1738–1762 (2016).

Blumenstock, J. & Eagle, N. Mobile divides: gender, socioeconomic status, and mobile phone use in Rwanda. In Proc. 4th ACM/IEEE International Conference on Information and Communication Technologies and Development 1–10 (ACM/IEEE, 2010)

Wesolowski, A., Eagle, N., Noor, A. M., Snow, R. W. & Buckee, C. O. Heterogeneous mobile phone ownership and usage patterns in kenya. PLoS ONE 7, 35319 (2012).

Wesolowski, A., Eagle, N., Noor, A. M., Snow, R. W. & Buckee, C. O. The impact of biases in mobile phone ownership on estimates of human mobility. J. R. Soc. Interface 10, 20120986 (2013).

I.T.U.: World Telecommunication/ICT Indicators Database (ITU, 2022).

Leo, Y., Fleury, E., Alvarez-Hamelin, J. I., Sarraute, C. & Karsai, M. Socioeconomic correlations and stratification in social-communication networks. J. R. Soc. Interface 13, 20160598 (2016).

Ricciato, F. et al. Estimating Population Density Distribution from Network-based Mobile Phone Data (Publications Office of the European Union, 2015).

Acosta, R. J., Kishore, N., Irizarry, R. A. & Buckee, C. O. Quantifying the dynamics of migration after Hurricane Maria in Puerto Rico. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 117, 32772–32778 (2020).

Salganik, M. J. Bit by Bit: Social Research in the Digital Age (Princeton Univ. Press, 2019).

Tizzoni, M. et al. On the use of human mobility proxies for modeling epidemics. PLoS Comput. Biol. 10, 1003716 (2014).

Pestre, G., Letouzé, E. & Zagheni, E. The ABCDE of big data: assessing biases in call-detail records for development estimates. World Bank Econ. Rev. 34, 89–97 (2020).

Blondel, V. D., Decuyper, A. & Krings, G. A survey of results on mobile phone datasets analysis. EPJ Data Sci. 4, 10 (2015).

De Montjoye, Y.-A. et al. On the privacy-conscientious use of mobile phone data. Sci. Data 5, 180286 (2018).

Rzeszewski, M. & Luczys, P. Care, indifference and anxiety-attitudes toward location data in everyday life. ISPRS Int. J. GeoInf. 7, 383 (2018).

Gerber, N., Gerber, P. & Volkamer, M. Explaining the privacy paradox: a systematic review of literature investigating privacy attitude and behavior. Comput. Secur. 77, 226–261 (2018).

Taylor, L. No place to hide? The ethics and analytics of tracking mobility using mobile phone data. Environ. Plann. D 34, 319–336 (2016).

Maxmen, A. Surveillance science. Nature 569, 614–617 (2019).

Stadler, J. et al. Cognitive mapping: using local knowledge for planning health research. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 13, 96 (2013).

Acknowledgements

L.P. thanks G. Cornacchia and G. Mauro for their valuable suggestions and D. Fadda for his precious support in visualizations. L.P. has been supported by EU projects: (1) H2020 HumaneAI-net G.A. 952026; (2) H2020 SoBigData++ G.A. #871042; (3) NextGenerationEU - National Recovery and Resilience Plan (Piano Nazionale di Ripresa e Resilienza, PNRR), project ‘SoBigData.it - Strengthening the Italian RI for Social Mining and Big Data Analytics’, prot. IR0000013, avviso n. 3264 on 28/12/2021. V.S. is supported by Digital Research Center Denmark (DIREC) grant P25—Understanding Biases and Diversity of Big Data used for Mobility Analysis. E.M. is supported by UK Research and Innovation (UKRI) through the Consumer Data Research Centre (ES/L011891/1) and Responsible Automation for Inclusive Mobility (ES/T012587/1) projects.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

L.A. and L.P. conceived the overall structure of the paper. All authors wrote the paper, reviewed the literature, contributed to figures and approved the final version of the paper. L.A. coordinated the work.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Computational Science thanks Pu Wang and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editor: Fernando Chirigati, in collaboration with the Nature Computational Science team.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Pappalardo, L., Manley, E., Sekara, V. et al. Future directions in human mobility science. Nat Comput Sci 3, 588–600 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43588-023-00469-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43588-023-00469-4

This article is cited by

-

Digital twins in city planning

Nature Computational Science (2024)

-

Defining a city — delineating urban areas using cell-phone data

Nature Cities (2024)