Abstract

Ocean warming is transforming the world’s coral reefs, which are governed by the growth of marine calcifiers, most notably branching corals. Critical to skeletal growth is the corals’ regulation of their internal chemistry to promote calcification. Here we investigate the effects of temperature and light on the calcifying fluid chemistry (using boron isotope systematics), calcification rates, metabolic rates and photo-physiology of Acropora nasuta during two mesocosm experiments simulating seasonal and static temperature and light regimes. Under the seasonal regime, coral calcification rates, calcifying fluid carbonate chemistry, photo-physiology and metabolic productivity responded to both changes in temperature and light. However, under static conditions the artificially prolonged exposure to summer temperatures resulted in heat stress and a heightened sensitivity to light. Our results indicate that temperature and light effects on coral physiology and calcification mechanisms are interactive and context-specific, making it essential to conduct realistic multi-variate dynamic experiments in order to predict how coral calcification will respond to ocean warming.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Reef-building corals are renowned for their ability to construct complex, three-dimensional reef frameworks through the biogenic accretion of their calcium carbonate (CaCO3) skeletons, forming ecosystems of considerable biological and socioeconomic importance1. However, the world’s oceans are both warming and acidifying at an unprecedented rate due to rising anthropogenic CO2 concentrations, posing a threat to all marine ecosystems, especially coral reefs2,3. The process of calcification is sensitive to declines in seawater pH and thus the aragonite saturation state of the seawater. Although some taxa show resistance to ocean acidification, responses are highly species-specific4,5 and ocean acidification is expected to result in decreased rates of calcification for many coral reefs6. Meanwhile, increasing ocean temperatures are triggering abrupt warming events that can last weeks to months3. When sea surface temperature exceeds the local summer maximum monthly mean (MMM), coral bleaching and mortality can occur due to the breakdown of the symbiosis with Symbiodiniaceae and the loss of the photosynthetic algal symbiont3. Summer-time temperatures are predicted to exceed localised thermal limits with increasing frequency and ocean warming is expected to correspond to extended summer temperatures and a shortening of the winter reprieve, particularly in the tropics7. Given that many corals are already living close to their upper thermal limits, these changes to seasonal thermal regimes are expected to further impact coral health, reef resilience and overall rates of calcification for many coral reefs worldwide7.

Corals are known to be highly adapted to their local seasonal temperature and light regimes, which can dictate the response of their physiology and calcification rates to changing ocean conditions. For instance, increasing temperature or light levels typically promote metabolism and stimulate calcification until a species- and location-specific optimum has been reached, after which calcification rates decline, and photosynthesis rates reach a plateau8,9,10. In addition to these key environmental controls, coral calcification is also a biologically mediated process dictated by several physio-chemical mechanisms11. One such mechanism is the corals’ ability to regulate their internal calcifying fluid chemistry, which in turn, dictates calcification rates11,12,13. The coral calcifying fluid pH (pHcf) and dissolved inorganic carbon (DICcf) can be characterized using a variety of techniques including microelectrodes14,15, pH-sensitive dyes13,16, and the boron isotope composition measured in the coral skeleton (δ11B) in conjunction with the elemental ratio of boron to calcium (B/Ca)17,18. Coral pHcf is typically upregulated 0.3 to 0.6 pH units above seawater and DICcf is approximately 1.4 to 3.2-fold higher than seawater DIC when integrated over timescales of weeks to months. This elevates the saturation state of the calcifying fluid (Ωcf) to promote calcification12,13,18,19,20. A decline in seawater pH drives a decrease in pHcf and often promotes an offsetting biologically mediated increase in DICcf, however, the magnitude of these changes is species-specific12,21,22.

The effects of temperature and light on pHcf and DICcf are less clear and there are still gaps in our understanding of how thermal stress might influence bio-calcification mechanisms. For instance, heat stress has been found to disrupt the regulation of DICcf23 but does not affect the regulation of pHcf and/or δ11B composition in most23,24,25, but not all26,27 coral skeletons. However, heat stress signals in coral pHcf or the skeletal δ11B composition may not be easily differentiated from indirect temperature-driven declines in coral pHcf that have been found on natural reef systems18,23,25,28,29,30 and further supported using numerical modelling31. Laboratory studies to date have also produced contrasting results with respect to both temperature and light effects on pHcf. These range from no effects of temperature at 25° and 28 °C24,32, to only small positive effects of temperature (equivalent to ~0.02 pHcf units) between temperatures of 22° and 25 °C33. Similarly, the results for the influence of light on δ11B range from no effects of light or depth34 to very small negative effects of light on δ11B (equivalent to 0.04 pHcf units) for branching Acropora33. More recently, light was found to have a positive effect on pHcf for Plesiastrea versipora, but no effect on pHcf for Acropora yongei35.

Clear diurnal variations in the calcifying fluid chemistry in response to light and dark cycles indicate that pHcf increases in response to a light-driven increase in rates of photosynthesis and/or holobiont metabolic productivity15,36. Field-based studies have documented clear seasonal trends in both coral pHcf and DICcf as well as the strong negative relationships between pHcf and temperature18,25,28,29,30,37. This is consistent with an increase in the buffering capacity when DICcf is higher, which lowers the pHcf31. Dynamic seasonal changes in the regulation of the calcifying fluid chemistry have not been detected in short-term culturing experiments to date, highlighting the importance of longer-term experiments that incorporate seasonal cycles in key environmental variables. Several studies on corals cultured under different temperature and light regimes have coupled measurements of key physiological variables, such as respiration and photosynthetic rates together with calcification rates and the calcifying fluid chemistry15,23,33,38. The individual and combined effects of temperature and light on calcification mechanisms under both seasonally variable and constant conditions remain a key knowledge gap.

A major challenge of disentangling the effects of temperature and light on coral growth and physiology is that they co-vary seasonally. The naturally occurring 3 to 4 month lag between seasonal changes in temperature and light in some tropical reefs has provided a framework to partially isolate the effects of temperature from seasonally co-varying light, revealing the strong effect of temperature on pHcf versus the relatively muted influence of light on pHcf29,30. However, the ability to characterize the relative importance of different drivers of the calcification fluid chemistry and calcification rates is still limited by the capacity to fully decouple the effects of seasonal changes in light from seasonal changes in temperature due to their phase coherence. Decoupling the effects of temperature and light on key aspects of the calcification process therefore remains a knowledge gap that must be addressed given the importance of the calcifying fluid carbonate chemistry in dictating the response of coral calcification to future climate change.

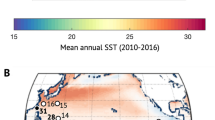

To address these questions, we conducted two culturing experiments with seasonally variable and static temperature and light conditions for a common branching coral species, Acropora nasuta, collected from a Ningaloo Reef, Western Australia (23°S, 113°E). Using this dual-experiment approach, we simulate natural seasonal conditions as well as artificially prolonged exposure (> 2 months) to four different temperature regimes. We combine measurements of geochemical proxies (skeletal B/Ca and δ11B) to reconstruct key components of the coral calcifying fluid carbonate chemistry (pHcf, [CO32-]cf, and DICcf) with rates of calcification, respiration and photosynthesis, and photo-physiology as a proxy for coral health (photochemical efficiency; Fv/Fm). Our results show complex links between metabolic productivity, calcifying fluid carbonate chemistry (DICcf, pHcf) and calcification rates for A. nasuta. We further show the influence of artificially sustained exposure to local maximum summer temperatures on coral physiology and calcification. Our results highlight that different experimental temperature and light regimes in aquaria can result in variable physiological response patterns with implications for the design of future mesocosm studies in order to better understand how corals will respond to climate change under realistic ocean conditions.

Results

Photo-physiology

Seasonal conditions

Photochemical efficiency (Fv/Fm) in the seasonal experiment ranged from 0.60 to 0.66 (Fig. 1a). The lowest Fv/Fm occurred during summer when temperature and light levels were highest (SLST; Fig. 1a). Fv/Fm was negatively correlated with seasonal changes in light (r2 = −0.14, p = 0.040; Fig. 2a) and there were interactive effects of temperature, light and time (Table S1). However, there was minimal seasonal coherency in Fv/Fm in the treatments that had constant light (Fig. 1a). For this reason, light was the most important factor influencing Fv/Fm on seasonal timescales when temperatures are maintained below the bleaching threshold of 28 °C.

Changes in Fv/Fm (mean ± 1 SE) during (a) the seasonal experiment and (b) static experiment. Temporal changes in calcification rates during (c) the seasonal experiment and (d) static experiment. Treatment conditions in the seasonal experiment are as follows: constant light and constant temperature (CLCT), seasonal light and constant temperature (SLCT), constant light and seasonal temperature (CLST), and seasonal light and seasonal temperature; (SLST). Treatment conditions for the static experiment are high and low light levels fully crossed with four temperatures. Note different date range on x-axis for each panel.

Matrix of Pearson Correlation Coefficients and Importance Scores based on Akaike weights corrected for sample size (ωAICc) from linear mixed model analyses for (a) the seasonal experiment and (b) the static experiment exploring the influence of temperature, light, and time on the pH of the calcifying fluid (pHcf), carbonate ion concentration in the calcifying fluid ([CO32-]cf), dissolved inorganic carbon in the calcifying fluid (DICcf), gross photosynthesis rate (Pgross), net photosynthesis rate (Pnet), net dark respiration rate (Rnet), calcification rate (G-rate), and photochemical efficiency (Fv/Fm). For ωAICc, a value of 1 is highly important while 0 is least important. Asterisks denote significant models and n.d. indicates where temporal data (>1 time point) were not available to test time as a factor.

Static conditions

Fv/Fm in the treatments with high light and high temperature (27 H and 28 H) decreased from ~0.68 to ~0.57 (Fig. 1b). The lowest Fv/Fm was found for coral growing in the 27 H and 28 H treatments (ANOVA, LSD, p < 0.005, Fig. 1b) and these corals showed paling and early signs of bleaching. Overall, light was the most important factor for explaining changes in Fv/Fm (Fig. 2b). Fv/Fm was significantly lower in the high light treatments than the low light treatments at all four temperatures (22 °C: ANOVA, LSD, p = 0.011; 24.5 °C: p = 0.015; 27 °C: p < 0.005; 28 °C: p < 0.005). In the low light treatments, Fv/Fm was significantly lower at 28 °C than 24.5 °C and 22 °C (ANOVA, LSD, p = 0.019 and p = 0.016; Fig. 1b). However, no visible signs of bleaching were observed in the corals growing under low light. Temperature, light and time also exhibited a significant interactive effect on Fv/Fm (Table S1). The synergistic effects of prolonged light and temperature were therefore important for driving changes in Fv/Fm.

Photosynthesis and respiration rates

Seasonal conditions

Photosynthesis rates were approximately 40 to 60 % lower in winter compared to summer (Fig. 3a). Both temperature and light influenced photosynthesis and dark respiration rates (Fig. 2a; Table S2). A significant interactive effect of light and time was found (Table S2). Dark respiration rates declined by 50 and 67 % in winter compared to summer for the two seasonally variable temperature treatments, CLST and SLST, respectively (Fig. 3a). There was minimal change in dark respiration rates under the constant temperature treatments CLCT and SLCT (Fig. 3a). Overall, temperature was the most important predictor of photosynthesis and dark respiration rates (Fig. 2a; Table S2).

Changes in (a, b) net photosynthesis and dark respiration rates, (c, d) calcifying fluid dissolved inorganic carbon (DICcf), (e, f) calcifying fluid pH (pHcf), (g, h) calcifying fluid carbonate ion concentration ([CO32-]cf), and (i, j) calcification rates for the coral Acropora nasuta. Values shown are mean ± SE. On the left is experiment 1 during summer (stripes) and winter (no stripes) for the three treatments with seasonally variable temperature and/or light, and the control treatment (grey). On the right is experiment 2 showing each of the eight temperature and light treatments at the end of the experiment. Treatment conditions for experiment 1 are the following: constant light and constant temperature (CLCT), seasonal light and constant temperature (SLCT), constant light and seasonal temperature (CLST), and seasonal light and seasonal temperature; (SLST). Treatment conditions for experiment 2 consist of high (28H, 27H, 24.5H, and 22H) and low (28 L, 27 L, 24.5 L, 22 L) light diurnal PAR cycles at each of the four temperatures (28 °C, 27 °C, 24.5 °C, and 22 °C).

Static conditions

Dark respiration rates were higher under high light and photosynthesis rates were lower under high light compared to low light (Fig. 3b). The light was the most important predictor of photosynthesis and dark respiration rates (Fig. 2b; Table S2). The effects of temperature and light on metabolic productivity was therefore quite different between the seasonal experiment and the static experiment, with the temperature being more important on seasonal timescales and light being more important under static conditions.

Calcifying fluid carbonate chemistry

Seasonal conditions

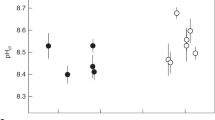

In the seasonal temperature treatments, CLST and SLST, the pHcf ranged from ~8.42 during summer to ~8.60 during winter (Fig. 3e). This increase of 0.18 units in winter corresponded to a change in pHcf of ~0.05 / °C. There was also a significant effect of light on pHcf (Table S3). However, pHcf varied by just 0.05 units in the treatments with seasonal light and constant temperature, SLCT (Fig. 3e). On seasonal timescales, the temperature was the most important predictor of calcifying fluid pH (pHcf; Fig. 2a). Temperature, light and time had an interactive effect on coral DICcf (Table S3). Coral DICcf varied by ~15 % in the constant light and seasonal temperature treatment (CLST), with values ranging from ~3,800 mol kg−1 in winter to 4,400 mol kg−1 in summer (Fig. 3c). However, changes in DICcf were relatively minor (± 3 %) through time in the other three treatments (Fig. 3c). Coral [CO32-]cf varied seasonally with light and increased by ~20% and ~8% during winter in the SLST and SLCT treatments, respectively (Fig. 3g). The change in [CO32-]cf in the CLST treatment was minimal (± 6 %; Fig. 3g; Fig. S1). Temperature and time were important factors for the amount of carbonate in the calcifying fluid [CO32-]cf (Fig. 2a; Table S3).

Static conditions

In the static experiment, pHcf ranged from 8.43 to 8.55 (Fig. 3f) and was negatively correlated with light (Table S3; Fig. 2b). Light and temperature had a significant effect on pHcf, but light was also the most important predictor variable for pHcf (Table S3; Fig. 2b). Light was also the most important predictor variable for DICcf (Fig. 3b). DICcf was positively correlated with light and was ~20 % higher under high light compared to low light (Table S3, Fig. 3d). Coral [CO32-]cf was influenced by temperature and light (Fig. 2b) but was relatively stable (±6 %) across all treatments ranging from just 930 to 1,040 mol kg−1 (Fig. 3h).

Calcification rates

Seasonal conditions

Calcification rates were generally higher in summer and lower in winter due to temporal changes in temperature and light in the seasonal experiment. Calcification rates decreased by 45 to 55% during winter compared to summer in the seasonal treatments: SLST, SLCT, and CLST (Fig. 1c). Calcification rates were correlated with both temperature and light (Fig. 2a). Light, temperature and time had significant main and interactive effects on calcification rates (Table S4).

Static conditions

Calcification rates were ~50 % higher in the high light treatments for the first 3 months of the static experiment (Fig. 1d) and hence were positively correlated with light (Fig. 3, Fig. 2b). However, calcification rates declined over time due to exposure to artificially prolonged summer temperatures in the 27 °C and 28 °C high and low light treatments (Fig. 1d). There were significant main and/or interactive effects of temperature, light and time on calcification rates (Table S4).

Relationships between coral response variables

Seasonal conditions

Dark respiration rates were negatively correlated with pHcf (Fig. 4a). Higher respiration was coupled with lower pHcf (Fig. 4a). There was a negative correlation between DICcf and pHcf such that higher pHcf corresponded to lower DICcf (Fig. 4a). Dark respiration rates were positively correlated with DICcf and calcification rate indicating that higher dark respiration rates (i.e., higher uptake of O2 and thus CO2 production) corresponds to higher DICcf and calcification rates. In contrast, pHcf and [CO32-]cf were negatively correlated with calcification rates. Coral pHcf was also negatively correlated with rates of photosynthesis and respiration (Fig. 4a).

Matrix of Pearson Correlation Coefficients for relationships between photochemical efficiency (Fv/Fm), net dark respiration rates (Rnet), net photosynthesis rates (Pnet), gross photosynthesis rates (Pgross), dissolved inorganic carbon in the calcifying fluid (DICcf), pH of the calcifying fluid (pHcf), carbonate ion concentration in the calcifying fluid ([CO32-]cf), and the calcification rate (G-rate) for (a) the seasonal experiment, and (b) the static experiment. Asterisk (*) denotes significant relationships.

Static conditions

DICcf and pHcf were negatively correlated such that higher pHcf corresponded to lower DICcf (Fig. 4b). Dark respiration rates were positively correlated with DICcf and calcification rate. However, pHcf and [CO32-]cf were negatively correlated with calcification rates. Coral pHcf was positively correlated with rates of photosynthesis and negatively correlated with respiration rate and DICcf (Fig. 4b).

Discussion

Deciphering the influence of temperature and light on the calcification mechanisms of branching Acropora is important for assessing how the growth of key reef builders may change with ocean warming. Here, we show that on seasonal timescales, coral calcification rates follow changes in both temperature and light. However, under static conditions, the artificially prolonged exposure (> 2 months) to summer temperatures of 27° and 28 °C results in heat stress and declines in calcification rates over time. We find that the effects of temperature and light are interactive, context-specific, and highly influenced by exposure time to different treatment conditions.

Seasonal conditions: Disentangling the seasonal effects of temperature and light

Photosynthesis and respiration rates were higher during summer and lower during winter in the seasonal experiment. Temperature and light both influenced photosynthesis rates, whereas temperature was a more important driver of respiration rates on seasonal timescales. Overall, these observations are in good agreement with many previous studies showing positive effects of both temperature and light on metabolism33,39,40,41,42. The metabolism of the symbionts is also known to play an important role in the light and/or temperature‐driven supply of DIC in the form of metabolic CO2 to the coral18,43,44. The positive relationship between dark respiration rates and DICcf indicates that increased metabolic CO2 productivity associated with higher respiration rates may contribute to higher DICcf and overall calcification rates43. Dark respiration rates could, however, be expected to mainly influence DICcf during periods of darkness, whereas the calcifying fluid parameters presented here reflect signals integrated over multiple weeks.

An antithetic relationship exists between pHcf and DICcf, which has been previously documented for a range of species (Table S6). This is consistent with a decrease in pHcf due to an increase in the buffering capacity of calcifying fluid when DICcf is higher4,18,21,25,30,31. The relationship between pHcf and DICcf is generally consistent among species and locations whereby most, but not all, corals show a decline in pHcf at a gradient of ~0.19 to 0.43 units with increasing DICcf/DICsw (Table S6). DICcf is typically 1.4 to 3.2 times higher than ambient seawater when integrated over timescales of weeks to months18,21,22,25,30,45, and may differ to those measurements on hourly to daily timescales using micro-elctrodes14. Coral DICcf was also influenced by both temperature and light, whereas seasonal changes in pHcf were mainly driven by temperature, and to a lesser extent light; indicating differences in the environmental controls. Previous field studies have shown a temperature driven change in pHcf18,29,30, which has also been explored using numerical modelling31. This is consistent with the influence of temperature on aragonite precipitation kinetics, buffering capacity, metabolism and DICcf18,25,30,31. We found that the seasonal range in pHcf in the variable temperature treatments (SLST, CLST) was much larger (~0.18 units) than the constant temperature treatments (~0.05 units in CLCT, SLCT), indicating that temperature is the primary control over pHcf. These findings together with results from previous studies indicate that the temperature-driven decline in pHcf is generally ubiquitous in corals (Table S5). However, a clear response of pHcf to temperature is generally only detected under seasonally variable temperature and light, which highlights the importance of natural variation in key environmental conditions. The temperature dependence (slope) of pHcf differs between locations and coral taxa with a decrease in pHcf ranging from 0.01 to 0.05 per °C (Table S5). The slope of the temperature-pHcf response could be expected to shift systematically based on temperature due to the abiotic rate kinetics of aragonite precipitation31. However, this does not appear to be the case for all zooxanthellae taxa, indicating factors other than local temperature may influence the strength of the slope of the relationship between temperature and pHcf.

The calcification rates of A. nasuta in the seasonal experiment were positively correlated with temperature and light. This is consistent with light-enhanced calcification and the positive effect of temperature on metabolic rates and DICcf as well as the temperature-dependent rate kinetics of aragonite precipitation46,47,48,49. For instance, the temperature is often found to be the primary driver of calcification rates in controlled aquaria experiments8,9 and field studies48,50. Previous work has also found that there is a strong positive relationship between the calcifying fluid carbonate chemistry, in particular pHcf and [CO32-]cf, and rates of calcification30. While not measured here, another important parameter for calcification is the coral calcifying fluid calcium concentrations ([Ca2+]cf), which tends to vary on seasonal timescales consistent with changes in calcification rates. The aragonite saturation state of the calcifying fluid (Ωcf) is also elevated to promote calcification, but is generally more stable on seasonal timescales30. Due to the influence of temperature on pHcf (and hence [CO32-]cf), an interesting paradox is that calcification rates are generally positively correlated with either temperature or [CO32-]cf, but not both. Given the importance of understanding temperature-growth responses in reef-building corals, such as Acropora, further research is required to decipher why the seasonal calcification rates of some branching corals are primarily driven by temperature and/or light while others are not.

Static conditions: Thermal stress and the effects of light

Under static conditions, the prolonged exposure to seawater temperatures that were close to (27 °C), or above (28 °C), the local upper summer thermal threshold resulted in heat stress and enhanced sensitivity to light. Reduced Fv/Fm, photosynthesis rates, and calcification rates occurred in the 27 °C and 28 °C high light treatments after ~8 weeks. Under lower light levels, declines in Fv/Fm occurred much later (~16 weeks) in the 27 °C and 28 °C treatments. This is consistent with previous work showing that temperature and light can act synergistically to influence coral bleaching responses. For example, the light intensity can play a role in exacerbating thermal stress while substantially reduced light can alleviate stress9,51,52,53. These responses are often highly species-specific and may be influenced by adaption and/or acclimatisation to local conditions. For tropical corals living close to their upper thermal limits, calcification rates often sharply decline in response to thermal stress once temperatures approach or exceed the upper thermal threshold or MMM8,9,46. However, we documented a negative impact of prolonged summer temperatures even when the temperatures remained within the upper limits of the natural seasonal range54. This highlights the increasing vulnerability of corals to ocean warming and prolonged maximum summer temperatures, even when temperatures remain below the typical bleaching threshold.

Under the static temperature and light levels, light was the main driver of changes in DICcf and pHcf. Our findings of a light-driven change in pHcf, albeit under relatively low light levels, is consistent with one previous study that documented a decrease in pHcf in cultured corals observed under enhanced light intensity33. One explanation for this finding is that there may be an enhanced effect of light when corals are light limited. Although coral symbionts can adjust to varying light levels seasonally by regulating chlorophyll-a concentrations and tissue densities, previous work has shown that light levels below 200 mol m−2 s−1 can result in reduced rates of photosynthesis55. Photosynthesis-irradiance curves were not measured in this study and can be highly species- and location-specific. However, it is possible that the corals in this relatively static experiment may have experienced lower light saturation and an increased sensitivity to light, potentially contributing to the relatively muted responses of pHcf and DICcf to temperature.

Another possibility is that thermal stress may have influenced both DICcf and pHcf because the skeletal material for geochemical analyses was sampled at the end of the experiment when the corals in the high-temperature treatments were showing signs of sub-lethal stress (paling and declines in Fv/Fm). Previous work has shown that thermal stress can differentially impact DICcf and pHcf23. Although not measured here, coral [Ca2+]cf may also be influenced by thermal stress due to the energy required to replenish [Ca2+] required for calcification. The heat-stressed Acropora in this study nevertheless maintained both DICcf and pHcf at levels elevated above seawater (DICcf above 1.5 x seawater and pHcf above 8.3 compared to seawater ~8.0). These findings are further support that both DICcf and pHcf are elevated and counter-regulated to maintain a threshold aragonite saturation state (Ωcf) for calcification even during instances where thermal stress impairs coral calcification rates due the loss of the photosynthetic symbionts. These findings show that the links between pHcf and calcification are not necessarily always clear, particularly during instances of thermal stress where the photosynthetically fixed carbon pool available to the coral is affected25,27. Due to the importance of the calcification mechanisms of reef-building Acropora, further research is required to understand how changes in the calcifying fluid carbonate chemistry will influence calcification under future ocean warming.

Conclusions

The findings from these two culturing experiments demonstrate that the effects of temperature and light on coral photo-physiology and calcification mechanisms are highly context-specific. Calcification rates were highest under high temperature and light, but only when exposed to maximum summer temperatures for short periods that were consistent with natural seasonal fluctuations. The clear relationship between temperature and pHcf reported in previous field studies (Table S5) was only detectable under conditions that mimicked natural seasonal changes in temperature and light. This highlights the importance of seasonally variable light and temperature levels and using mesocosm conditions that closely reflect those at the site of coral collection.

Notably, we find that the effects of light and temperature on coral physiology are complex and interactive. Under static conditions, we observed light-enhanced thermal stress under artificially prolonged exposure to summer temperatures. Although the heat-stressed corals were able to maintain elevated pHcf and DICcf, their calcification rates were impaired. This indicates that prolonged summer temperatures under future ocean warming will likely result in sublethal stress and reduced calcification56, particularly for those corals such as Acropora whose calcification mechanisms are highly sensitive to heat stress23. Prolonged summer temperatures will continue to be particularly problematic as corals are known to be highly adapted to their local temperature regimes and already living close to the upper thermal limits57. Coral bleaching due to marine heatwaves is currently the foremost threat to coral reef survival3. The future vitality of coral reefs therefore ultimately depends on urgent global efforts to rapidly and substantially mitigate CO2 emissions to reduce the impacts of climate change.

Methods

Coral collection and aquaria set-up

We conducted two culturing experiments simulating seasonally variable and static temperature and light conditions (Table 1) for the coral species Acropora nasuta collected from Ningaloo Reef, Western Australia (23°S, 113°E). The study species was branching A. nasuta, which has a broad geographic distribution spanning 104 ecoregions, globally58. Individual colonies of A. nasuta were collected from a depth of ~2 m in Coral Bay for experiment 1 (n = 8 colonies) during December 2016 and for experiment 2 (n = 6 colonies) during June 2017. Samples were transported from Coral Bay to the Waterman’s Bay Indian Ocean Marine Research Facility in Perth, Western Australia in insulated cooler tubs with fresh seawater and battery-operated air pumps. The colonies were maintained in flow-through mesocosm tanks with sand filtered, freshly pumped seawater. Fragments of approximately 5 cm in length were glued to pre-labelled acrylic plates using cyanoacrylate glue (Ecotech Elements Coral Glue). One fragment of each parent colony was used for each treatment combination for each experiment. After plating the corals, they were given a 1-week recovery period before gradually adjusting temperature and light to the treatment conditions.

The temperature in all tanks was maintained using 500 W titanium aquarium heaters (Weipro) connected to a temperature control system (Apex, Neptune systems) regularly calibrated using a high-precision thermometer (Fisher Scientific Traceable). For experiment 1, the variance between the tanks for any given month was ± 0.20 °C, and for experiment 2, the variances in mean temperature of the replicate treatment tanks were ± 0.10 °C. The light was provided by LED aquarium lights (LEDZEAL) with custom-designed LED configuration to represent the light spectrum in shallow tropical waters. The tanks received no natural sunlight input and light levels were measured using an Apogee MQ-200 light meter at the level of the coral specimens in each tank. Light was cycled to mimic natural daily cycles with a linear ramp up from darkness to maximum output from 06:00 to 11:00, with a maximum output for two hours followed by a linear ramp down to darkness at 18:00. Moonlight was not simulated in the light cycle. Seawater was circulated with pumps (DC wavemaker pumps, Macro Aqua, China) and freshly pumped filtered seawater (corresponding to a mesh size of 25 µm) was continuously delivered to the tanks at approximately 2 to 3 L min−1. Corals were fed brine shrimp (Ocean nutrition) at the end of the day twice weekly.

Seasonal experiment

The seasonal experiment spanned 9 months and tested seasonal temperature and light treatments. This design mimicked the typical seasonal conditions in temperature and light experienced by A. nasuta in its natural reef environment over one summer and one winter30. Eight individuals (1 per colony) of A. nasuta were placed into each of the four treatments (Table 1). There were two 30 L tanks per treatment and the experiment lasted for 9 months. The four treatments were: constant light and constant temperature (hereafter CLCT), seasonal light and constant temperature (SLCT), constant light and seasonal temperature (CLST), and seasonal light and seasonal temperature (SLST; Table 1 and Fig. 5). Conditions in the seasonally variable temperature and/or light treatments mimicked the natural cyclical seasonal timing and were within the range of the natural conditions experienced at Ningaloo where average monthly seawater temperature typically ranges from approximately 22° to 27 °C but can be much lower during summer (25° to 26 °C) during colder years (e.g. strong El Niño) and can be much higher (28° to 29 °C) during marine heatwave conditions (e.g. La Niña) (NOAA, 2019). The coastal waters of Western Australia experience a 3 to 4 month offset in the phasing of light and temperature, in part due to the poleward flowing Leeuwin Current, which brings warm water along the coast from April to September. For this reason, there are only limited periods in the seasonal treatment (SLST) when high temperature overlaps with high light and when low temperature overlaps with low light (Fig. 5). Temperatures during experiment 1 did not exceed the bleaching threshold (MMM + 1 °C; NOAA, 2019) and were maintained at 27 °C for just 4 weeks, which is consistent with the duration that these MMM temperatures would occur in the field where the coral were collected from at Coral Bay, Ningaloo30. Monthly averaged PAR (daily dose) reaching the benthos at 2 m depth ranges from approximately 13 to 40 mol m−2 d−1,30. This seasonal range in daily mean light levels corresponds to a maximum daily noon PAR reaching the benthos of ~900 mol m−2 s−1 for just 1 to 2 hours during the summer solstice (December) and ~500 mol m−2 s−1 during the winter solstice (June). For the seasonally variable conditions, the light maximum (solstice) occurs in December whereas the seawater temperature maximum typically occurs 3 to 4 months later in March or April and hence a lag exists between temperature and light. In accordance with these changes in temperature and light, for this study summer is defined as 15th November through to 15th May, while winter is defined as 16th May through to 14th November. Given that the seasonal treatments commenced at the end of December 2016 and finished in early October 2017, the seasonal means (i.e., averaged over 6-month seasonal blocks) correspond to temperatures of 23.2 °C during winter and 26.0 °C during summer, and a mean daily dose of PAR of 18.8 mol m−2 d−1 during winter and 27.1 mol m−2 d−1 in summer. Shade curtains were installed between each of the tanks to prevent the light leaking between treatments. A total of 4 corals died at the beginning of the experiment, which reduced the replication to n = 6 for SLST, n = 7 for SLCT, and n = 7 for CLST.

a Seasonal range in the diurnal light cycles for the seasonal experiment, and (b) the high and low diurnal light cycles for the static experiment. c, d Weekly averaged seawater temperature (blue lines) and daily PAR (grey lines) in the seasonal study, and (e) seawater temperature (green and yellow lines) and daily PAR (grey lines) in the static experiment. Dark blue shading denotes the intervals reflected in coral skeletal sampling for geochemistry. The light blue shading indicates when photosynthesis and respiration rate measurements were conducted. Treatment conditions are the following: constant light and constant temperature (CLCT), seasonal light and constant temperature (SLCT), constant light and seasonal temperature (CLST), and seasonal light and seasonal temperature; (SLST).

Static experiment

The static experiment spanned 4 months and tested static exposure to temperature and light, with four temperatures fully crossed with two light levels. Six individuals (1 per colony) of A. nasuta were placed into two 40 L tanks per temperature treatment (Table 1). The eight treatments included four temperatures fully crossed with two light levels (Table 1; Fig. 5). The high light treatment was selected because it reflects typical light levels of many shallow reefs and the low light treatment reflects light levels that corals may experience under high cloud cover or in reduced light positions, such as deeper reef waters or in cervices30. The corals were placed in positions receiving the required light levels from LED lights. The four temperatures treatments are within the range of the natural conditions experienced at the coral collection site in Coral Bay where seawater temperature ranges from approximately 22° to 27 °C30. The temperature treatments were selected because 22 °C reflects winter, 24.5 °C is the annual mean, 27 °C reflects the MMM and 28 °C is the bleaching threshold30. Furthermore, the seawater temperature in Coral Bay rarely exceeds 27 °C for more than 4 weeks and does not generally exceed 28 °C for more than a few days, except during heatwave conditions (NOAA Coral Reef Watch, 2021). The duration of this experiment was 4 months including an initial acclimation period and ramp-up to treatment conditions of ~1 month, followed by treatment conditions for ~3 months (Table 1).

Coral photo-physiology and calcification measurements

Coral calcification rates, calcifying fluid carbonate chemistry, photochemical efficiency (Fv/Fm), net photosynthesis rates, and dark respiration rates were measured during both experiments. For calcification, the changes in weight were measured using the buoyant weight technique and were normalised to surface area (calculated based on the geometric technique) using regressions between surface area and dry weight as per previous methods59,60. The maximal quantum yield of electron transport through photosystem II (Fv/Fm; photochemical efficiency) was measured using a Diving-PAM (Walz, Germany). Measurements of Fv/Fm were performed approximately 45 to 60 minutes after darkness and coral plates were cleaned before measurement using a soft cloth to remove any turf algae growth. The fibre optic probe on the PAM fluorometer was kept at a fixed distance (5 mm) using plastic tubing. The PAM settings used were as follows: measuring intensity (3), gain (3), saturation intensity (12) and signal width (0.8).

Coral photosynthesis and respiration rate measurements

Net photosynthesis and dark respiration rates were measured using oxygen production and consumption method via incubations. For measurements of net photosynthesis and dark respiration rates, samples were placed in fully sealed 1 L acrylic chambers containing seawater from the treatment tank. Dissolved oxygen (DO) content relative to air (Thermo orionstar A323 RDO), temperature and salinity (YSI 85 O2, conductivity, salinity, and temperature probe) were recorded before and after an incubation time of approximately 60 minutes. Time was varied as required, based on the size of the coral fragments to achieve a change in % DO of at least 10% during the incubation. A two-point calibration of the DO meter was carried out daily using 0% DO seawater achieved by a saturated solution of sodium sulphite, and 100% DO (relative to air) seawater by aeration with an air stone for at least 30 minutes. Incubations were conducted in a temperature-controlled water bath at the same temperature as the respective treatments. Water movement within chambers was achieved using magnetic stirrers at 400 rpm. Irradiance levels matching the respective treatment at noon were maintained using the same LED lights as those used for the treatment tanks. For all incubations, a control chamber with the same filtered seawater as in the experiments containing no sample was used and any change in DO (DOE – DOI) subtracted from the sample readings. Incubation water volume (V) in L was measured using a measuring cylinder at the end of the incubation. Dark respiration incubations were repeated in the same way on a different day, within two days of the light incubation, on samples subject to at least 1 h of darkness. Dark incubations were typically about 90 min. Results were normalised to coral surface area. The density of the seawater (D) in kg L−1, and concentration of DO in mg L−1 (DOI = initial, DOE = final) at the measured temperatures and salinities were determined using the marelac R package.

Coral geochemical measurements

For the geochemical analyses to derive the calcifying fluid carbonate chemistry, we sampled the uppermost section of the apical tip of the A. nasuta skeleton representing 3 to 4 weeks of new CaCO3 growth, as per previous methods30. This ensured complete removal of the previous 3 to 4 weeks of apical growth, which was followed by visually tracking the re-growth of a new apical tip that solely represented the experimental conditions during each time period in-between sampling. The powder weight used for the analyses was 10 mg. Powders derived from the sampled coral skeleton were cleaned using 6% NaOCl solution and samples were then acidified in 0.58 N HNO3. Trace element analyses (Sr/Ca, Mg/Ca, Ba/Ca, U/Ca and B/Ca) were performed on aliquots of the acidified samples using an X-Series 2 Quadrupole Inductively Coupled Plasma Mass Spectrometer (Q-ICPMS; Thermo Fisher Scientific). The extraction of boron from the acidified sample solutions was performed via paired cation-anion resin columns. All chemical dissolution and boron extraction procedures were undertaken in the metal-free hepa-filtered (ISO 7) cleanroom complex at the University of Western Australia (UWA)61. Solutions were then analysed with a NU Plasma II (Nu Instruments, Wrexham, UK) multi-collector inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometer (MC-ICPMS) at the Advanced Geochemical Facility for Indian Ocean Research (AGFIOR), UWA61. Measurements of the international coral standard JCp-1 (Geological Survey of Japan, Tsukuba, Japan) yielded a mean value of 24.28 ± 0.11 ‰ (mean ± SE, n = 7), which was similar to the 24.33 ± 0.11 ‰ (SE) reported previously. For the measurements of B/Ca, the JCp-1 yielded an analytical uncertainty of 2.5% at 2σ and a mean value of 458 ± 1.2 µmol mol−1 (mean ± SE, n = 22), which are in good agreement with previously published values62. Calcifying fluid pH (pHcf) and dissolved inorganic carbon (DICcf) were calculated using the δ11B proxy method for pHcf20 and the δ11B and B/Ca method for [CO32-]cf and DICcf as per previous methods17,18. The pHcf was derived from the measured skeletal δ11B values according to the following equation:

where pKB is the dissociation constant of boric acid in seawater63 at the temperature and salinity of the seawater, δ11Bcarb and δ11BSW are the boron isotopic composition of the coral skeleton and average seawater (39.61‰), respectively, and αB is the isotopic fractionation factor (1.0272). All pH values are expressed on the total scale (pHT).

We estimated the concentration of carbonate ions at the site of calcification ([CO32-]cf) using molar ratios of boron to calcium (B/Ca) according to the following relationship17,18:

where [B(OH)4-]cf is the concentration of borate in the calcifying fluid, and is pH-dependent and thus derived from δ11B, \({K}_{D}^{B/{Ca}}\) is the distribution coefficient for boron between aragonite and seawater that has been re-fit as a function of [H+], and [B/Ca]arag is the elemental ratio of boron to calcium measured in the coral skeleton17,18. A strong linear relationship exists between the derived [CO32-]cf (using Eq. 3.2) and the known [CO32-]cf from abiotic experiments17. The \({K}_{D}^{B/{Ca}}\) is calculated as a function of [H+] according to18:

where [H+] in the calcifying fluid is estimated from the coral δ11B-derived pHcf and only varies by less than ± 3% over the range in which most coral pHcf generally occur (8.3 to 8.6)64. The concentration of DICcf was then calculated from the estimates of pHcf and [CO32-]cf18.

Statistical analyses

Linear mixed-effects modelling examined the individual and interactive effects of temperature, light, and time on coral response variables. Tank and coral fragment were included as random factors, as per the recommended treatment of dependent units65 and to account for repeated measures, respectively. Temperature and light were time‐averaged in all instances to reflect the same interval as each coral response parameter. Models were compared using Akaike Information Criteria corrected to sample size (AICc) and AICc weight (ω) values. The model with the lowest AICc value was assumed to be the optimal model, and the ωAICc determined the relative contribution of each predictor metric (temperature, light, and time) such that the higher ωAICc corresponded to higher importance in the analysis. A Pearson’s correlation matrix was used to investigate the relationships between coral response variables (calcification rates, calcifying fluid carbonate chemistry, Fv/Fm, net photosynthesis rates, and dark respiration rates) and treatment variables (temperature, light, and time). A one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to test for significant differences between treatment for Fv/Fm. Dark respiration rates were converted to a positive integer for ease of interpretation of statistical results. Gross photosynthesis rates were calculated by subtracting dark respiration from the net photosynthesis. Before conducting analyses, dependent variables were tested for normality (Shapiro-Wilk test) and for sphericity (Mauchly’s test). In this study, significance is defined as p < 0.05. Statistical analyses were performed using the fitlme function in MATLAB (The MathWorks, Natick, MA, USA) and Pearson correlations were performed in SPSS statistical software (IBM, Foster City, CA, USA).

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Research Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

Data is available at the Zenodo Digital Repository https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.6216201.

References

Moberg, F. & Folke, C. Ecological goods and services of coral reef ecosystems. Ecol. Econ. 29, 215–233 (1999).

Poloczanska, E. S. et al. Responses of marine organisms to climate change across oceans. Front. Mar. Sci. 3, 62 (2016).

Hughes, T. P. et al. Global warming and recurrent mass bleaching of corals. Nature 543, 373–377(2017).

Cornwall, C. E. et al. Resistance of corals and coralline algae to ocean acidification: physiological control of calcification under natural pH variability. Proc. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 285, 20181 (2018).

Schoepf, V. et al. Coral energy reserves and calcification in a high-CO2 world at two temperatures. PLoS One 8, e75049 (2013).

Kroeker, K. J. et al. Impacts of ocean acidification on marine organisms: quantifying sensitivities and interaction with warming. Glob. Chang. Biol. 19, 1884–1896 (2013).

Heron, S. F., Maynard, J. A., Van Hooidonk, R. & Eakin, C. M. Warming trends and bleaching stress of the world’s coral reefs 1985-2012. Sci. Rep. 6, 38402, 1–14 (2016).

Marshall, A. T. & Clode, P. Calcification rate and the effect of temperature in a zooxanthellate and an azooxanthellate scleractinian reef coral. Coral Reefs. 23, 218–224 (2004).

Jokiel, P. L. & Coles, S. L. Effects of temperature on the mortality and growth of Hawaiian reef corals. Mar. Biol. 208, 201–208 (1977).

Rodolfo-Metalpa, R., Huot, Y. & Ferrier-Pagès, C. Photosynthetic response of the Mediterranean zooxanthellate coral Cladocora caespitosa to the natural range of light and temperature. J. Exp. Biol. 211, 1579–1586 (2008).

Cohen, A. L. & McConnaughey, T. A. Geochemical perspectives on coral mineralization. Rev. Mineral. Geochemistry 54, 151–187 (2003).

McCulloch, M. T., Falter, J. L., Trotter, J. & Montagna, P. Coral resilience to ocean acidification and global warming through pH up-regulation. Nat. Clim. Chang. 2, 1–5 (2012).

Venn, A. A., Tambutté, É., Holcomb, M., Allemand, D. & Tambutté, S. Live tissue imaging shows reef corals elevate pH under their calcifying tissue relative to seawater. PLoS One 6, e20013 (2011).

Cai, W.-J. et al. Microelectrode characterization of coral daytime interior pH and carbonate chemistry. Nat. Commun. 7, 11144 (2016).

Al-Horani, F. A., Al-Moghrabi, S. M. & de Beer, D. The mechanism of calcification and its relation to photosynthesis and respiration in the scleractinian coral Galaxea fascicularis. Mar. Biol. 142, 419–426 (2003).

Holcomb, M. et al. Coral calcifying fluid pH dictates response to ocean acidification. Sci. Rep. 4, 5207 (2014).

Holcomb, M., DeCarlo, T. M., Gaetani, G. A. & McCulloch, M. T. Factors affecting B/Ca ratios in synthetic aragonite. Chem. Geol. 437, 67–76 (2016).

McCulloch, M. T., D’Olivo, J. P., Falter, J., Holcomb, M. & Trotter, J. A. Coral calcification in a changing World: the interactive dynamics of pH and DIC up-regulation. Nat. Commun. 8, 15686 (2017).

Tambutté, S. et al. Calcein labelling and electrophysiology: insights on coral tissue permeability and calcification. Proc. R. Soc. B 279, 19–27 (2012).

Trotter, J. et al. Quantifying the pH ‘vital effect’ in the temperate zooxanthellate coral Cladocora caespitosa: Validation of the boron seawater pH proxy. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 303, 163–173 (2011).

Schoepf, V., Jury, C. P., Toonen, R. & McCulloch, M. Coral calcification mechanisms facilitate adaptive response to ocean acidification. Proc. R. Soc. B 284, 2117 (2017).

Comeau, S., Cornwall, C. E. & McCulloch, M. T. Decoupling between the response of coral calcifying fluid pH and calcification to ocean acidification. Sci. Rep. 7, 7573 (2017).

Schoepf, V., D’Olivo, J. P., Rigal, C., Jung, E. M. U. & Mcculloch, M. T. Heat stress differentially impacts key calcification mechanisms in reef-building corals. Coral Reefs. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00338-020-02038-x (2021).

Schoepf, V. et al. Short-term coral bleaching is not recorded by skeletal boron isotopes. PLoS One 9, e112011 (2014).

D’Olivo, J. P. & McCulloch, M. T. Response of coral calcification and calcifying fluid composition to thermally induced bleaching stress. Sci. Rep. 7, 2207 (2017).

Dishon, G. et al. A novel paleo-bleaching proxy using boron isotopes and high-resolution laser ablation to reconstruct coral bleaching events. Biogeosciences 12, 5677–5687 (2015).

Guillermic, M. et al. Thermal stress reduces pocilloporid coral resilience to ocean acidification by impairing control over calcifying fluid chemistry. Sci. Adv. 7, 20172117(2021).

Ross, C. L., Falter, J. L. & McCulloch, M. T. Active modulation of the calcifying fluid carbonate chemistry (δ11B, B/Ca) and seasonally invariant coral calcification at sub-tropical limits. Sci. Rep. 7, 1–11 (2017). 13830.

D’Olivo, J. P., Ellwood, G., Decarlo, T. M. & Mcculloch, M. T. Deconvolving the long-term impacts of ocean acidification and warming on coral biomineralisation. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 526, 115785 (2019).

Ross, C. L., DeCarlo, T. M. & McCulloch, M. T. Environmental and physiochemical controls on coral calcification along a latitudinal temperature gradient in Western Australia. Glob. Chang. Biol. 25, 431–447 (2019).

Guo, W. Seawater temperature and buffering capacity modulate coral calcifying pH. Sci. Rep. 9, 1–13 (2019).

Reynaud, S., Ferrier-Pagès, C., Boisson, F., Allemand, D. & Fairbanks, R. G. Effect of light and temperature on calcification and strontium uptake in the scleractinian coral Acropora verweyi. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 279, 105–112 (2004).

Dissard, D. et al. Light and temperature effects on δ11B and B/Ca ratios of the zooxanthellate coral Acropora sp.: results from culturing experiments. Biogeosciences 9, 4589–4605 (2012).

Hönisch, B. et al. Assessing scleractinian corals as recorders for paleo-pH: Empirical calibration and vital effects. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 68, 3675–3685 (2004).

Comeau, S. et al. Flow-driven micro-scale pH variability affects the physiology of corals and coralline algae under ocean acidification. Sci. Reports 9, 1–12 (2019). 2019 91.

DeCarlo, T. M., Ross, C. L. & McCulloch, M. T. Diurnal cycles of coral calcifying fluid aragonite saturation state. Mar. Biol. 166, 1–6 (2019).

Ross, C. L., Schoepf, V., DeCarlo, T. M. & McCulloch, M. T. Mechanisms and seasonal drivers of calcification in the temperate coral Turbinaria reniformis at its latitudinal limits. Proc. R. Soc. B 285, 20180 (2018).

Krief, S. et al. Physiological and isotopic responses of scleractinian corals to ocean acidification. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 74, 4988–5001 (2010).

Coles, S. L. & Jokiel, P. L. Effects of temperature on photosynthesis and respiration in hermatypic corals. Mar. Biol. 43, 209–216 (1977).

Gattuso, J.-P., Allemand, D. & Frankignoulle, M. Photosynthesis and calcification at cellular, organismal and community levels in coral reefs: a review on interactions and control by carbonate chemistry. Am. Zool. 39, 160–183 (1999).

Kajiwara, K., Nagai, A., Ueno, S. & Yokochi, H. Examination of the effect of temperature, light intensity and zooxanthellae concentration on calcification and photosynthesis of scleractinian coral Acropora pulchra. J. Sch. Mar. Sci. Technol. Tokai Univ. 40, 95–103 (1995).

Reynaud, S. et al. Interacting effects of CO2 partial pressure and temperature on photosynthesis and calcification in a scleractinian coral. Glob Chang. Biol. 9, 1660–1668 (2003).

Furla, P., Galgani, I., Durand, I. & Allemand, D. Sources and mechanisms of inorganic carbon transport for coral calcification and photosynthesis. J. Exp. Biol. 203, 3445–3457 (2000).

Zoccola, D. et al. Bicarbonate transporters in corals point towards a key step in the evolution of cnidarian calcification. Sci. Rep. 5, 9983 (2015).

Allison, N. et al. Corals concentrate dissolved inorganic carbon to facilitate calcification. Nat. Commun. 5, 5741 (2014).

Vajed Samiei, J. et al. Variation in calcification rate of Acropora downingi relative to seasonal changes in environmental conditions in the northeastern Persian Gulf. Coral Reefs. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00338-016-1464-6 (2016).

Kuffner, I. B., Hickey, T. D. & Morrison, J. M. Calcification rates of the massive coral Siderastrea siderea and crustose coralline algae along the Florida Keys (USA) outer-reef tract. Coral Reefs. 32, 987–997 (2013).

Courtney, T. A. et al. Environmental controls on modern scleractinian coral and reef-scale calcification. Sci. Adv. 3, e170135 (2017).

Burton, E. A. & Walter, L. M. Relative precipitation rates of aragonite and Mg calcite from seawater: Temperature or carbonate ion control? Geology 15, 111 (1987).

Lough, J. M. & Barnes, D. Environmental controls on growth of the massive coral Porites. J. Exp. Mar. Bio. Ecol. 245, 225–243 (2000).

Fitt, W. K., Brown, B., Warner, M. E. & Dunne, R. Coral bleaching: interpretation of thermal tolerance limits and thermal thresholds in tropical corals. Coral Reefs. 20, 51–65 (2001).

Fisher, R., Bessell-Browne, P. & Jones, R. Synergistic and antagonistic impacts of suspended sediments and thermal stress on corals. Nat. Commun. 10, 1–9 (2019).

Teixeira, C. D. et al. Sustained mass coral bleaching (2016–2017) in Brazilian turbid-zone reefs: taxonomic, cross-shelf and habitat-related trends. Coral Reefs. 38, 801–813 (2019).

Bonesso, J. L., Leggat, W. & Ainsworth, T. D. Exposure to elevated sea-surface temperatures below the bleaching threshold impairs coral recovery and regeneration following injury. PeerJ 5, e3719 (2017).

Ulstrup, K. E., Kühl, M., van Oppen, M. J. H., Cooper, T. F. & Ralph, P. J. Variation in photosynthesis and respiration in geographically distinct populations of two reef-building coral species. Aquat. Biol. 12, 241–248 (2011).

Lough, J. M. & Cantin, N. E. Perspectives on massive coral growth rates in a changing ocean. Biol. Bull. 226, 187–202 (2014).

Howells, E. J., Berkelmans, R., van Oppen, M. J. H., Willis, B. L. & Bay, L. K. Historical thermal regimes define limits to coral acclimatization. Ecology 94, 1078–1088 (2013).

Veron, J. E. N. Corals of the world. Townsville, Australia (Australian Institute of Marine Science, 2000).

Foster, T., Short, J., Falter, J. L., Ross, C. & McCulloch, M. T. Reduced calcification in Western Australian corals during anomalously high summer water temperatures. J. Exp. Mar. Bio. Ecol. 461, 133–143 (2014).

Ross, C. L., Falter, J. L., Schoepf, V. & McCulloch, M. T. Perennial growth of hermatypic corals at Rottnest Island, Western Australia (32°S). PeerJ 3, e781 (2015).

McCulloch, M. T., Holcomb, M., Rankenburg, K. & Trotter, J. A. Rapid, high-precision measurements of boron isotopic compositions in marine carbonates. Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom. RCM 28, 2704–2712 (2014).

Okai, T., Suzuki, A., Kawahata, H., Terashima, S. & Imai, N. Preparation of a new Geological Survey of Japan geochemical reference material: Coral JCp-1. Geostand. Newsl 26, 95–99 (2002).

Dickson, A. G. Thermodynamics of the dissociation of boric acid in synthetic seawater from 273.15 to 318.15 K. Deep Sea Res. Part A. Oceanogr. Res. Pap. 37, 755–766 (1990).

McCulloch, M. T. et al. Resilience of cold-water scleractinian corals to ocean acidification: Boron isotopic systematics of pH and saturation state up-regulation. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 87, 21–34 (2012).

Cornwall, C. E. & Hurd, C. L. Experimental design in ocean acidification research: problems and solutions. ICES J. Mar. Sci. 73, 572–581 (2015).

Acknowledgements

Thanks to J. D’Olivo and R. Berdin for assistance in the isotope and mass spectrometry laboratories. Thanks to F. McGregor for field assistance and to Murdoch University for access to accommodation and facilities at the Coral Bay Research Station. We are very grateful to volunteers (S. Bell, L. Dugal, S. Dawe, T. Bassett, L. Krzus, B. Moore, T. DeCarlo, and M. Jung) for assistance in the field and at the Waterman’s Bay Indian Ocean Marine Research Facility. This research was supported by funding provided by an ARC Laureate Fellowship (LF120100049) awarded to M. McCulloch, the ARC Centre of Excellence for Coral Reef Studies (CE140100020), and an Australian Post Graduate Scholarship awarded to C. Ross.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

C.L.R.: conception and design, sample collection, laboratory experiments, data acquisition, data analysis and interpretation, wrote first original manuscript, manuscript revision; A.W.: conception and design, sample collection, laboratory experiments, data acquisition, data analysis and interpretation, manuscript revision; S.C.: conception and design, data acquisition, supervision, manuscript revision; C.E.C: conception and design, data acquisition, supervision, manuscript revision; M.C: sample collection, data analysis, manuscript revision; M.N.: laboratory experiments, data acquisition, manuscript revision; M.T.M.: conception and design, supervision, manuscript revision; V.S.: conception and design, laboratory experiments, data acquisition, supervision, manuscript revision.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Earth & Environment thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editor: Heike Langenberg.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ross, C.L., Warnes, A., Comeau, S. et al. Coral calcification mechanisms in a warming ocean and the interactive effects of temperature and light. Commun Earth Environ 3, 72 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-022-00396-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-022-00396-8

This article is cited by

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.