Abstract

Ordinary Portland cement (OPC) is the core ingredient of many construction materials. In 2022, 4.1 billion tons were used worldwide, contributing to ~8% of CO2 emissions ( ~ 3 Gt/year). Nevertheless, the complete strength-generating capacity of OPC remains unrealized due to the restricted conversion of aluminates to ettringite, caused by conventional hydration kinetics. Here we show a hydration control additive that selectively modifies the hydration kinetics, thereby facilitating enhanced dissolution of aluminates (calcium aluminoferrite and tricalcium aluminate) in OPC, which promotes ettringite formation at a desired time. Increasing ettringite content improves packing of the hardened cement, resulting in ~50% higher specific strength and enabling cement reduction. It also increases OPC strength development efficiency, reducing carbon footprint by ~30%. The use of this additive can be combined with methods such as reducing water and/or using supplementary cementitious materials (SCMs) to prepare building materials with significantly fewer CO2 emissions than those from conventional OPC.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The main component of OPC and the material that gives it strength, clinker, is produced by sintering a well-defined raw meal made of limestone mixed with one or more sources of Si, Al, and Fe at approximately 1450 °C1. During this process, the limestone decomposes to CaO and releases CO2, which is the primary source of CO2 emissions in Portland cement manufacturing2. To decrease the carbon footprint of cement-containing materials, the amount of clinker used in the final material must be reduced given its prominent role in the CO2 emissions associated with these materials. Apart from the optimization of energy and raw material sources during the cement production process, this is currently accomplished by two main approaches: (1) reducing the water to cement ratio (w/c)3 and 2) substituting clinker with SCMs2,4,5. These solutions have limitations in their rheological and strength performance and can contribute only partly to the goal of carbon neutrality of the cement industry by 2050 until affordable carbon capture, utilization and storage (CCUS) technologies6 and/or other disruptive innovation7 become viable.

OPC clinker consists of several mineral phases, namely, tricalcium silicate (C3S, for details about cement nomenclature see supplementary), dicalcium silicate (C2S), tricalcium aluminate (C3A) and calcium aluminoferrite (C4AF)1. An external CaSO4 source (typically gypsum, anhydrite, or bassanite) is added to OPC clinker during the grinding or sometimes the mixing process to produce the final cement to control the reaction of C3A.

When the cement is mixed with water, reactive minerals start to dissolve, and strength-building hydrates including ettringite (Ca6Al2(SO4)3(OH)12·26H2O)), calcium silicate hydrate (C-S-H) and Ca(OH)2 are formed at different rates based on the different reactivities of each clinker mineral phase8. As soon as the cement meets water, the most reactive phase C3A starts to react. In the absence of CaSO4, the cement undergoes rapid hardening and delays the C3S reaction. The addition of CaSO4 slows down the C3A reaction9, allowing the C3A and C3S reactions to occur simultaneously. The CaSO4 content is optimized10 to prevent the formation of ettringite after the main C3S reaction, which prevents expansion of the hardened cement11,12. As a result, only a partial conversion of aluminate to ettringite occurs. It should be noted that the initially formed ettringite before casting the cement does not significantly contribute to strength. The primary contributor to strength and setting speed is the C3S, which reacts with water to form C-S-H and Ca(OH)2, resulting in a hardened structure within a few hours. Therefore, considerable research13,14,15,16 focuses on the hydration of C3S and its hydrates, specifically C-S-H.

The full potential of OPC to build strength remains untapped. Not only a small portion of the aluminates converts to ettringite, but also C4AF mostly acts as an inert material at the beginning of hydration15. There are some ways to enhance the dissolution of aluminate phases e.g. using alkanolamines or glycols17,18,19,20,21, but usually comes with limitation because of their inhibiting effect on the C3S reaction and negative impact on workability19. Combinations of retarders, accelerators, and sulfate improve workability but struggle with proper strength development20. In summary, unlocking the full strength-building capacity of OPC requires overcoming the limitations in aluminates conversion to ettringite and the inert behavior of C4AF during hydration.

In this paper, we present our Hydration Control additive (HyCon® B) which fundamentally alters the hydration process by shifting the main reactions of C4AF and C3A before the C3S reaction forming high amount of ettringite. With calorimetry, XRD Rietveld analysis coupled with thermal dynamic modeling, the overall new hydration process was presented. To evaluate the performance, we conducted mechanical tests, pore structure analysis, assessed sulfate attack resistance and the carbon footprint. We compared our model binder mix (70 wt% OPC, 7 wt% anhydrite, and 23 wt% limestone powder with 1.11 % solid of HyCon® B refer to total solid) with two control groups: 100 wt% OPC and 70 wt% OPC with 30 wt% limestone powder. Characteristics of the raw materials are given in Supplementary Table 1.

Results and discussion

Hydration stages of OPC with HyCon® B

The initial dissolution and wetting peak in the calorimetry diagram is significantly depressed by HyCon® B additive compared to the controls (Fig. 1a) due to the strong inhabitation of the nucleation of ettringite caused by the oligomer poly[urea-alt-(glyoxylic acid)] (PUG) in HyCon® B together with Na2CO322 (see also see Supplementary Fig. 1a–f). This is supported by pore solution analysis performed after 5 min of hydration (Supplementary Table 2). The high concentration of aluminum in the pore solution further slows the dissolution of C3A, C4AF and C3S, significantly inhibiting the formation of ettringite leads to the 1st induction period.

(a) heat flow during the first 0.5 h from in situ calo, (b) heat flow during the first 6 h, (c) heat flow during the first 3 d, and (d) cumulative heat released during the first 3 d. Hydration stages of conventional OPC labeled as gray boxes; the new hydration stages with HyCon® B labeled as orange boxes. The arrow in (b) shows the extremely slow heat release during the 1st induction period with HyCon® B compared to the heat released during the conventional OPC hydration reaction. Anh. - anhydrite.

In the sample with HyCon® B, the 1st induction period shows minimal exothermicity and reaction rates, lasting for ~3 h (Fig. 1a), depending on the dosage level of HyCon® B. The heat flow during this duration is significantly lower than the induction period observed in the controls (Fig. 1b). HyCon® B completely prevents the reaction of cement phases with water after the initial dissolution and wetting stage. In contrast, conventional OPC hydration involves a substantial amount of C3A reacting immediately after mixing with water, leading to the formation of ettringite (Figs. 1a and 2d). Although the rate of this reaction slows down after a few minutes, it continues at a very slow pace during the induction period of conventional OPC23, which is typically responsible for undesired changes in OPC rheology during various applications22,24,25.

Hydration stages: 1st Ind. – 1st induction; 1st Alu. – 1st aluminate (C3A and C4AF) reaction; 2nd Ind. – 2nd induction; C3S and 2nd Alu. – reaction of C3S and 2nd aluminate restart. Anh. – anhydrite. (d) is the reaction products of aluminate phase represented by (a) and (b); (e) is the reaction product of C3S from (c).

The 1st aluminate reaction rapidly restarts after the 1st induction period in the presence of HyCon® B before the silicate reaction (mainly C3S), which constitutes the first primary reaction (Fig. 1a, peak starting at 3 h). HyCon® B promotes the dissolution of C4AF and C3A during hydration, leading to the rapid release of heat (Fig. 1c) through ettringite formation (Fig. 2d). Such effect was mainly achieved via the combination of TEA19,20,21 and glycerol, which was known to be able to accelerate the aluminate reaction (Supplementary Fig. 1a–f). This process consumes 60% of C3A, 50% of C4AF, and 72% of anhydrite within the first 5 h (Supplementary Figs. 2 and 3b–d). Notably, a significant amount of ettringite (15 g per 100 g paste) forms from the reacted aluminate phases, resulting in a rapid increase in strength (Fig. 3j) as early as 5 h. In contrast, in conventional OPC hydration, the main aluminate reaction is slowed down by CaSO4 to occur partially in parallel with the main C3S reaction (Fig. 1c).

Phase composition of the hardened pastes using thermal dynamic modeling for by GEMS (a–c); BSE images of the hardened paste samples (d–i); compressive strength of a standard mortar according to EN 196-1 (water to solid ratio 0.5, cured at 23 °C under water) (j); correlation of the compressive strength and the porosity modeled by GEMS (k); and expansion of the mortar cured under Ca(OH)2 saturated water at 23 °C (l). Ettr ettringite, LS limestone powder. Drying cracks are the cracks because of damaged ettringite during the hydration stoppage process.

Following the rapid 1st aluminate reaction (Fig. 1b), a 2nd induction period occurs until ~15 h. The length of the dormant period of the 2nd induction period is likely influenced by the kinetics of defect formation on the surface of C3S and the formation of C-S-H nuclei. The high concentration of Al in the pore solution with HyCon® B (as shown in Supplementary Table 2) may prolong this period. This is also the reason why a significant high amount of anhydrite was needed to react with the released Aluminum from pore solution forming ettringite.

During the 1st aluminate reactions, ettringite formation acts as a filler and can impact the hydration kinetics of C-S-H26. C-S-H surfaces in cement pore solution conditions (pH = ~12.6, Ca = ~20 mmol per liter, Supplementary Table 2) have partially deprotonated silanol groups, resulting in negative charges ranging from 1–3 e−nm−2 (ref. 27). The zeta potential is negative without calcium but becomes positive with the presence of 20 mmol per liter calcium in the pore solution due to calcium ion adsorption. Sulfate ions decrease this potential, but it remains positive under pore solution conditions. Ettringite carries a positive charge of 1.25 e- nm-2 28, but under pore solution conditions with sulfate ions, the zeta potential decreases to values ranging from −15 to −20 mV. Studies29,30 using Monte Carlo simulation have analyzed the forces between oppositely charged surfaces in multivalent ion solutions. These studies found that under low to medium concentrated solutions, such as those present in cementitious pore solution, the surfaces are still attractive, but the attractive forces are relatively small. This is consistent with the SEM images (Supplementary Fig. 4d, f), which show that ettringite primarily forms on the surfaces of clinker phases and limestone powder rather than on the ettringite needles. Limited C-S-H growth occurs on ettringite surfaces.

Subsequently, the C3S reaction commences, resulting in the formation of nanocrystalline C-S-H (Fig. 3c) and Ca(OH)2 (Fig. 2e). Concurrently, the 2nd aluminate reaction takes place as the embedded aluminate phases and/or alumina impurity in C3S within the clinker grain are exposed because of the C3S reaction. After 7 days, the hydration levels of C4AF and C3A in the presence of HyCon® B are significantly higher, approaching 100%, compared to the control samples (at 70%), as depicted in Supplementary Fig. 3c, d. The extent of the C3S reaction is similar between the model and control samples (Fig. 2 (c) and Supplementary Figure 3 (a)), but it is delayed in the presence of HyCon® B.

The overall hydration process with HyCon® B produces significantly more heat than that of the controls due to the increase in aluminate reaction and ettringite formation. The total amount of heat released in the sample with 70 wt% OPC modified with HyCon® B even surpasses that of the 100% OPC reference after ~2 days (Fig. 1c). The total amount of heat released correlates well with the development of strength (Supplementary Figure 5 (a)).

High temperatures can compromise the structural integrity of materials by causing thermal expansion or the decomposition of ettringite into meta-ettringite, resulting in expansion and cracking upon rehydration. When limestone is used to reduce clinker, along with the addition of HyCon® B, it releases a significant amount of energy (Fig. 1d) which raises the temperature of the samples (Supplementary Figs. 7 and 8). Despite this increase in temperature, the sample containing HyCon® B reaches a similar or even lower peak temperature compared to the reference samples, as demonstrated in Supplementary Fig. 8. Furthermore, the early strength provided by HyCon® B (Fig. 3j) helps prevent cracking by adequately compensating for any length changes that may occur, as evidenced in Supplementary Figs. 9 and 10.

After 1 year, the final amount of ettringite in the model with the additive is double the amount in the 100% OPC control (Fig. 2d).

Sulfate balance

With HyCon® B, a significantly greater amount of CaSO4 can be added to the cement to enhance the formation of ettringite, approaching the theoretical limit of spacing filling with OPC clinker, as indicated at point C in Fig. 4. The experimental points A, B, and C fall within the green range labeled as OPC + Anh. + HyCon® B. This range represents samples with varying levels of anhydrite and the addition of the hydration control additive, ranging from 4% to 10% anhydrite in the 70% OPC system. Achieving such a range is not possible with the conventional OPC system due to the premature formation of ettringite, as indicated by the red range labeled as OPC in Fig. 4). Results from compressive strength testing indicate that the optimal percentage of anhydrite in the 70% OPC system for achieving the highest strength is 7% (Supplementary Fig. 11a).

The theoretical space filling of the OPC was controlled by the anhydrite content, which was adjusted to regulate the reaction of C3A (red range labeled OPC). Experimental points A, B, and C in the green range OPC + Anh. + HyCon® B correspond to the samples with the hydration control additive together with additional anhydrite.

With the formation of increasing amounts of ettringite with additional sulfate, the prisms expand slightly before 2 days due to the 2nd aluminate reaction forming ettringite ((Fig. 3l and Supplementary Fig. 11a, b). There is hardly expansion after 2 days (Supplementary Fig. 11c, d). This is because that most of the theoretically possible ettringite forms before the start of the C3S reaction when there is almost no or little stress in the structure, which prevents cracking and failure31,32. This reaction consumes ~80% of the available sulfate (Supplementary Fig. 3b). The large initial conversions of C3A, C4AF, and CaSO4 prevent subsequent formation of ettringite and other aluminate hydrates, decreasing the long-term risks of expansion during the further reaction or storage in Na2SO4 solution (sulfate attack) (Fig. 3l and Supplementary Fig. 12)33. The high early conversion of aluminate to ettringite is not only beneficial for durability against sulfate attack and potentially other durability issues due to late age aluminate reaction, but also results in higher strength.

Although the addition of HyCon® B leads to an increase in the final reaction degree of OPC, the overall GEMs modeled chemical shrinkage does not show a significant increase. This can be attributed to the increased formation of ettringite, as shown in Figs. 4 and 3a–c.

Microstructure and compressive strength

An ettringite-fiber-reinforced structure formed within the microstructure of the hardened sample, as shown in the backscattered electron (BSE) images (Fig. 3f, i and the images in Supplementary Fig. 13). After 1 d, the hydrated matrix of the sample with HyCon® B was filled with long needles of ettringite (Fig. 3f) that formed a denser network than that of the controls. The C3S reaction occurred after ettringite filled the cavities of the network, resulting in a compact composite structure.

The final hydrate volume is increased by the enhanced formation of ettringite with HyCon® B additive, resulting in a larger solid volume (Fig. 3c and Supplementary Fig. 14 and more chemically bound water (Supplementary Figs. 5b and 6). The enhanced packing density within the hardened structure contributes to greater strength (Fig. 3j and Supplementary Figs. 14 and 16a) according to Powers model34 which describes the relationship between the packing and strength. Based on the thermodynamic modeling of this cement used, the theoretical maximum amount of anhydrite is 14% (Fig. 4). 90 % OPC + 10 % anhydrite + HyCon® B represents a good compromise (point B in Fig. 4, corresponding to 70% OPC, 7% anhydrite for the strength) between strength and initial expansion (Supplementary Figs. 17a and 11). In contrast, filler in a conventional OPC system is mostly inert and substituting binders with filler results in dilution (Fig. 3j). Consequently, the 28-day strength is reduced, as evidenced by the comparison between the reference samples of 100% OPC control and 70% OPC control (Fig. 3j).

Due to the hydration kinetics optimization and microstructure densification, large early strength at 5 h (3.2 MPa) was obtained for the 70% OPC system with HyCon® B (Fig. 3j) right after the 1st aluminate reaction (Fig. 1a, c). For the two controls, the strength at 5 h was too small to be measured (labeled as 0 in Fig. 3j). After 1 d, the strength of the 70% OPC system with HyCon® B was slightly lower than 100% OPC control due to the delayed reaction of C3S. From 2 day on, the strength of mortar with HyCon® B increased significantly as the reaction of C3S proceeded, gradually reached a level similar to that of the 100% OPC control and continued to increase together with the control (Fig. 3j).

These strength results were consistent with the results for the total porosity obtained from thermodynamic modeling (Fig. 3k) as well as MIP porosimetry (Supplementary Figs. 14 and 16a). The lower total porosity (Fig. 3k and Supplementary Fig. 14) as well as the reduced proportion of pore within 5–10 nm achieved with HyCon® B reduces diffusion through the cement stone matric and is expected to reduce some durability issues of concrete.

The efficiency of OPC clinker producing strength is significantly enhanced by the HyCon® B. HyCon® B increases the specific strength at 28 days from 0.15 in the 100% OPC control to 0.23 MPa per (kg OPC per ton dry mortar) at a w/s ratio of 0.5 (Supplementary Table 3), and can be further increased to ~0.30 MPa per (kg OPC per ton dry mortar) when the w/s ratio was reduced to 0.4.

Carbon footprint impact

The improved strength of the cement offers opportunities to design construction materials by incorporating low-carbon footprint materials. Figure 5 and Supplementary Table 3 illustrate the CO2 footprint of the mortar mix design when HyCon® B is used. By combining the additive with conventional CO2 emission reduction methods, such as reducing water content (Fig. 5a) or incorporating supplementary cementitious materials (SCMs) such as calcined clay (the so-called limestone calcined clay cement (LC3)35,36) (Fig. 5b and Supplementary Fig. 17c), the carbon footprint of the building materials can be significantly reduced.

The circle size refers to the CO2 emission by the binder including additive (kg CO2 per ton binder). The green area corresponds to similar or greater strength but less CO2 emissions compared to the 100% OPC control. a Routine 1 uses OPC, limestone powder and anhydrite for the binder, and the effect of the additive combined with reduced water content is shown. b Routine 2 is an example of the use of SCMs in LC3 cement with the additive. The number in each circle represents the total CO2 emission per ton of binder.

Reducing water content enhances the strength of the cement stone (Routine 1b). By utilizing HyCon® B with a lower water-to-solid ratio of 0.4, the OPC content can be further reduced to 50 wt% (Fig. 5a) to achieve a similar strength level, while compensating with limestone powder, resulting in a final CO2 reduction ~46% compared to OPC control with water-to-cement ratio of 0.5. Reducing the water content in the OPC-limestone system is practical due to the rheology improving effect introduced by HyCon® B and the easy accessibility of limestone powder to the construction industry.

Another approach is to leverage the higher reactivity of calcined clays (Routine 2b in Fig. 5b). In the LC3 mix with HyCon® B, the OPC content can be further reduced to 40 wt%, significantly lowering the CO2 footprint by ~43% compared to OPC control while maintaining the same level of performance. This approach demonstrates promising potential as the use of calcined clay enhances the specific strength of OPC due to its high reactivity37 (Supplementary Table 3). Moreover, the future production of calcined clay at a larger scale has the potential to lower production costs and CO2 emissions associated with its production (we used the higher end value of 350 kg CO2/ton for this calculation2). However, reducing the water content in the LC3 mix poses a challenge due to the inherently high-water demand of calcined clay.

Conclusion

Our findings demonstrate the effectiveness of the hydration control additive (HyCon® B) in optimizing the process between formation of C-S-H and ettringite, resulting in a cement formulation with lower carbon emissions, increased strength, and improved durability. More work will be needed to understand the pore structure of the hardened cement, rheology, early age expansion/shrinkage, durability with the additive HyCon® B.

Materials and methods

Materials

Two CEM I 42.5N cements (OPC and OPC2) were used in this study. A CEM I 52.5 N cement (OPC3) was used for the sulfate attack test. Different cements were used in the tests in parallel to test the robustness of the system with different alkali content. OPC3 contains high aluminate (see Supplementary Table 1) which is more vulnerable to sulfate attack38,39. Calcined clay (CC) and limestone powder (LS) were used to make blended cement according to the mix design given in Supplementary Table 3 to explore the potential of additive in blended cement. Anhydrite (CaSO4) was used as the sulfate source due to its constant dissolution in low and high temperature. An identical OPC was used in the mix design when needed: OPC for the main research, OPC2 for the limestone calcined clay cement (LC3) system and OPC3 for the sulfate attack test. The characteristics of the raw materials are given in Supplementary Table 1. The strength data of the LC3 control system were previously reported by our group36.

A hydration control additive (HyCon® B) was developed to control the hydration of the aluminate phases (C3A and C4AF). The additive used in this paper (brand name HyCon® B) was similar to the Retarder A in WO 2023/02558540,41. HyCon® B is a solution of poly[urea-alt-(glyoxylic acid)] (PUG, 20 wt%), sodium carbonate (41 wt%), glycerol (21 wt%), triethanolamine (TEA, 11 wt%), and sodium gluconate (7 wt%) in de-ionized water. This additive is commercially available from BASF Construction Additives GmbH, Trostberg, Germany. Additionally, 0.1% and 0.3% stabilizer (Starvis® 3040 F) were introduced into the mortar samples (strength, expansion test) and paste kinetic experiment, respectively, to prevent bleeding due to the reduced amount of OPC in the OPC-limestone-anhydrite system and provide homogeneous structure. Stabilizer (Starvis® 3040 F) has little impact on the hydration and of the cement within the dosage level used32. When it was necessary to use a dispersant to adjust the workability which is the case for the experiment running at w/s 0.4 and where calcined clay was used, a commercially available polycarboxylate ether, Melflux® PCE 2500 L from BASF Construction Additives, Trostberg, Germany, was applied. Detailed information about the concentrations of the additives can be found in Supplementary Table 3.

Methods

The mortar strength test was conducted according to the EN 196-1 standard42, except that curing was performed at 23 ± 2 °C instead of 20 °C. All the dry components, including the powder additives and standard sand, were weighed, and premixed in a bucket for 30 s in a shaking mixer (Skandex SK550 1.1) before following the standard mixing procedure described in EN 196-1. The additives were added into the final blended cement as a percentage relative to the total solids content. Once the mixing procedure was completed, the mortar was poured into standard molds and covered with lids to prevent water evaporation during the curing process until 1 day before demolding. The demolded mortar bar samples were then submerged in water and kept in this condition until they were required for subsequent measurements. The compressive strength was measured at specific ages (5 h, 1, 2, 7, 28, 90, and 365 d) according to the EN 197-1 standard. The reported compressive strength was the mean of 4 replicates.

A flow table test was conducted based on a standard mortar according to EN 196-1 by following the protocol described in EN 1015-3. Fifteen shocks were applied before the spread of the mortar was measured at 5, 15, 30 and 60 min.

An expansion test was performed using the mortar prepared according to EN 196-1. The length at 1 day was measured as the initial length. The mortar samples remained under water at 23 °C. Expansion from 1 day was recorded at 2, 3, 7, 14, 28, and 90 days for 3 specimens. The reported expansion was the mean of 3 specimens.

A sulfate attack test was conducted using OPC3. Measurements were taken according to German standard DIN 19573. The mortar sample was cast with w/s 0.43 with 832 g of binder and 1917 g of sand. The mortar sample was first cured under water for 28 days under the same condition as the strength test before curing in 44 g/l Na2SO4 solution at 23 °C. Expansion after curing in Na2SO4 was measured and compared to that of the control stored in Ca(OH)2 saturated solution.

Isothermal calorimetry tests were performed using paste samples. One hundred grams of premixed blended binder was mixed with water (a water-to-solid ratio of 0.4, where solid refers to solid OPC or a mixture of OPC, limestone powder, and anhydrite) with an overhead mixer at 1600 rpm for 2 min. A thermal activity monitor (TAM) air calorimeter at 23 °C was used for the calorimetry experiments. Water (1.143 g) was used as a reference. Paste (4.29 g) was weighed in a glass ampule. Heat release data were collected for 7 days. For monitoring the initial wetting and dissolution, in-situ calorimetry was conducted using reaction vials containing 3000×g of the sample and the appropriate amount of deionized water with dissolved additive components in two syringes. The in-situ mixers were placed in the calorimeter and allowed to equilibrate overnight. The mixing procedure involved a 10-second pre-mixing of the dry powder, followed by the injection of water and continuous stirring for 60 seconds using an electric motor. The reactions were observed and recorded for a duration of 2–3 days.

The pore solution was analyzed by inductively coupled plasma optical emission spectroscopy (ICP-OES) according to references43,44. The pore solution was extracted from paste with w/s 0.5 after mixing for 5 min. The original extracted pore solution was diluted using ultra-filtered water at 1:10. HCl was used to neutralize the pore solution before the analysis.

X-ray diffraction (XRD) measurements were taken using Bruker D8 Advance diffractometers. More details about the XRD measurements and the Rietveld analysis routines can be found in Li et al. 45,46. In situ experiments were conducted on freshly mixed paste (prepared as described in the previous subsection) covered with a 3 µm thick Mylar® film. Data were collected between 5-70° continuously for ~24 h at ~14 min per scan using Bruker D8 Advance running at the following conditions: Cu radiation, tension 40 kV, current 30 mA, Radius 215 mm, divergence slit 0.5 °, sample spinning at 15 rpm, step size 0.028° and time per step 0.35 s. The temperature of the XRD chamber was 28 ± 2 °C during the measuring process. Fresh discs were measured immediately after they were cut and gently polished by hand and washed as described previously45,47 to prevent contamination and carbonation. XRD data between 5-70° for fresh discs were collected within ~10 min using Bruker D8 Advance with the following parameters: Cu radiation, tension 40 kV, current 35 mA, Radius 280 mm, divergence slit 0.3°, no sample spinning, step size 0.021° and time per step 0.20 s.

Rietveld analysis was performed using Bruker Diffrac. Suite TOPAS version 6. Parameters including cell parameters, crystallite size of the clinker phases such as C3S, C2S, C3A, and C4AF were extracted from the OPC analysis. Those parameters were fixed for the clinker phases in the hydrated samples (the insitu and fresh disc samples) analysis, only the scale factors was allowed to be refined. The scale factor, the unit cell, crystallite size, and March Dollase preferred orientation were refined for the crystalline hydrates. A 2nd order Chebyshev function along with a 1/x term was used for the background. An external standard method using CaF2 was used for the Rietveld analysis to evaluate the amorphous or unknown content. More details of the Rietveld protocol was reported by Li et al. 45 In situ XRD data were corrected based on the initial amount according to the mix design and the content of the fresh disc sample at 24 h, which was considered more accurate45,47.

The hydration stoppage of the hardened paste sample was carried out by using the solvent exchange method using ~3 mm thick slices with isopropanol following a protocol described in the literature47. The isopropanol was replaced at a time interval of 1 h, 1 and 2 days. The hydration stoppage process lasts 5–7 days. After the solvent exchange process, the discs were vacuum dried at 40 °C before stored in sealed vacuum bags for further analysis. These samples were used for TGA, SEM, and MIP analysis. During this process, ettringite tends to decompose partially depends how long the solvent exchange was carried out45,47. The decomposed ettringite will leave some characteristic drying cracks in the sample which can be seem under BSE image47,48 (Fig. 3i and Supplementary Fig. 13i) as well as in MIP with the characteristic pore entry size of ~130 nm (Supplementary Fig. 15).

Thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) was conducted using a TA Instruments TGA5500. After hydration was stopped, the disc sample was freshly ground before ~10 mg of the sample was loaded into the sample holder. During the measurement, the sample was heated from 30 °C to 1000 °C at a rate of 10 °C/min under N2 flow. The chemically bound water was calculated from the weight loss until 550 °C according to the recommended protocol47.

Thermodynamic modeling was performed using GEM-Selektor version 349 (GEMS) based on the database published by Lothenbach et. al. 50. The reacted cement clinker phases were obtained from the XRD Rietveld analysis, the modeling was performed at 23 °C and 101 KPa.

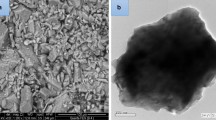

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) was performed using a JSM-IT500 from JEOL. Secondary electron (SE) images were collected of the powders obtained after the hydration of samples was stopped to investigate the morphology of the hydrated samples during the early hydration period (less than 1 d). The powders were coated using 10 nm gold/palladium to perform the SE experiment. Backscattered electron images of polished sections of the slices of paste after hydration was stopped that were coated with 10 nm of carbon were acquired.

Mercury intrusion porosimetry (MIP) was performed using a MicroActive AutoPore V 9600. Surface and edges of the hydration stopped discs samples (~3 mm thick) was removed by polishing with sandpaper, then the discs were broken into 2–5 mm pieces for MIP experiments. The contact angle of mercury to the cement paste sample was set to 140° according to Berodier et al. 51. Even though there is artifact due to decomposition of ettringite during the hydration stoppage process, the overall total pore volume correlation to GEMs modeled values still showed quite good fit (Supplementary Figure 16 (b)). The correlation of the MIP total pore volume to strength was slightly shifted due the artifacts (Supplementary Fig. 16a).

The temperature rises as well as cracks formation of the paste samples was investigated using a large volume of sample placed in a sealed plastic container with a diameter of Ø 11 cm. The samples were cured in a thermal container at room temperature (23 ± 2 °C), as depicted in Supplementary Fig. 7. For the test, each sample contained 2−2.5 kg of total solid. The temperature of the samples was monitored by inserting a thermal meter into the core of each sample. After three days of curing, the cement pastes were sliced in the middle and carefully polished by hand using sandpaper. The cross-sections of the samples were visually inspected, both with the naked eye and under a microscope, to identify any visible cracks.

The specific strength contribution of unit OPC was calculated as follows:

where \({{{{{\rm{\sigma }}}}}}\) is the compressive strength; 1350 and 450 refer to the grams of sand and binder in the standard mortar design according to EN 196-1, respectively; \({{{{{{\rm{W}}}}}}}^{{{{{{\rm{opc}}}}}}}\) is the weight fraction of OPC in the blended cement (including SCMs, limestone filler and anhydrite); and 1000 converts to units of MPa/(kg OPC in ton dry mortar).

The CO2 footprint for a mix design was calculated as follows:

where \({{{{{{\rm{CO}}}}}}}_{2}^{{{{{{\rm{binder}}}}}}}\) is the final CO2 footprint for the binder mix design in kgCO2/ton, \({{{{{{\rm{w}}}}}}}^{{{{{{\rm{i}}}}}}}\) is the weight fraction of the materials (binder or additive), and \({{{{{{\rm{CO}}}}}}}_{2}^{{{{{{\rm{i}}}}}}}\) is the CO2 footprint of the binder component. Product carbon footprint (PCF)52,53 data as of January 2023 from BASF were used for the chemical additives in this manuscript, and such data are subject to change due to changes in the carbon footprints of the raw materials and the energy makeup of production. The values of CO2 emissions for the binder and filler were taken from the literature as listed Supplementary Table 3.

The specific performance-based CO2 footprint was calculated based on compressive mortar strength following a similar approach reported previously54:

where \({{{{{{\rm{S}}}}}}}^{{{{{{\rm{CO}}}}}}2}\) is the performance-based CO2 footprint in units of (kg CO2)/(MPa ton dry mortar), \({{{{{\rm{\sigma }}}}}}\) is the compressive strength, and 1350 and 450 refer to the grams of sand and binder solid, respectively.

The data analysis was conducted using the statistical programming software R55 running via RStudio®. The package tidyverse56 was used to process the data.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the authors on reasonable request.

References

Taylor, H. F. Cement chemistry. Vol. 2 (Thomas Telford London, 1997).

Scrivener, K. L., John, V. M. & Gartner, E. M. Eco-efficient cements: potential economically viable solutions for a low-CO2 cement-based materials industry. Cem. Concr. Res. 114, 2–26 (2018).

Aïtcin, P. C. In Science and Technology of Concrete Admixtures (eds Aïtcin P.-C. & Flatt R. J.) 75–86 (Woodhead Publishing, 2016).

Habert, G. et al. Environmental impacts and decarbonization strategies in the cement and concrete industries. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. https://doi.org/10.1038/s43017-020-0093-3 (2020).

Shah, I. H., Miller, S. A., Jiang, D. & Myers, R. J. Cement substitution with secondary materials can reduce annual global CO2 emissions by up to 1.3 gigatons. Nat. Commun. 13, 5758 (2022).

CEMBUREAU. Cementing the European Green Deal (Cembureau, 2020).

Wu, L., Wang, D. & Evans, J. A. Large teams develop and small teams disrupt science and technology. Nature 566, 378–382 (2019).

Hewlett, P. & Liska, M. Lea’s Chemistry Of Cement And Concrete (Butterworth-Heinemann, 2019).

Quennoz, A. & Scrivener, K. L. Hydration of C3A–gypsum systems. Cem. Concr. Res. 42, 1032–1041 (2012).

Zunino, F. & Scrivener, K. Factors influencing the sulfate balance in pure phase C3S/C3A systems. Cem. Concr. Res. 133, 106085 (2020).

Lothenbach, B., Bary, B., Le Bescop, P., Schmidt, T. & Leterrier, N. Sulfate ingress in Portland cement. Cem. Concr. Res. 40, 1211–1225 (2010).

Mindess, S. Lea’s Chemistry of Cement and Concrete. 251–283 (Elsevier, 2019).

Pustovgar, E. et al. Understanding silicate hydration from quantitative analyses of hydrating tricalcium silicates. Nat. Commun. 7, 10952 (2016).

Morales-Melgares, A. et al. Atomic-level structure of zinc-modified cementitious calcium silicate hydrate. J. Am. Chem. Soc. https://doi.org/10.1021/jacs.2c06749 (2022).

Shirani, S. et al. 4D nanoimaging of early age cement hydration. Nat. Commun. 14, 2652 (2023).

Li, X. & Scrivener, K. L. Impact of ZnO on C3S hydration and C-S-H morphology at early ages. Cem. Concr. Res. 154, 106734 (2022).

Huang, H., Li, X., Avet, F., Hanpongpun, W. & Scrivener, K. Strength-promoting mechanism of alkanolamines on limestone-calcined clay cement and the role of sulfate. Cem. Concr. Res. 147, 106527 (2021).

Hirsch, T., Lu, Z. & Stephan, D. Effect of different sulphate carriers on Portland cement hydration in the presence of triethanolamine. Constr. Build. Mater. 294, 123528 (2021).

Lu, Z. et al. Towards a further understanding of cement hydration in the presence of triethanolamine. Cem. Concr. Res. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cemconres.2020.106041 (2020).

Kirchberger, I., Goetz-Neunhoeffer, F. & Neubauer, J. Enhancing the aluminate reaction during OPC hydration by combining increased sulfate content, triethanolamine and tartaric acid. Cem. Concr. Res. 170, 107188 (2023).

Ramachandran, V. S. Action of triethanolamine on the hydration of tricalcium aluminate. Cem. Concr. Res. 3, 41–54 (1973).

Jakob, C., Jansen, D., Dengler, J. & Neubauer, J. Controlling ettringite precipitation and rheological behavior in ordinary Portland cement paste by hydration control agent, temperature and mixing. Cem. Concr. Res. 166, 107095 (2023).

Scrivener, K., Ouzia, A., Juilland, P. & Kunhi Mohamed, A. Advances in understanding cement hydration mechanisms. Cem. Concr. Res. 124, 105823 (2019).

Quennoz, A. & Scrivener, K. L. Interactions between alite and C3A-gypsum hydrations in model cements. Cem. Concr. Res. 44, 46–54 (2013).

Nicia, D. et al. Thixotropy of superplasticized cement pastes – Underlying mechanisms considering the polycarboxylate molecular structure, interparticle interactions and hydration kinetics. Cem. Concr. Res. 173, 107289 (2023).

Berodier, E. & Scrivener, K. Understanding the filler effect on the nucleation and growth of C-S-H. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 97, 3764–3773 (2014).

Goyal, A. et al. The physics of cement cohesion. Sci. Adv. 7, eabg5882 (2021).

Labbez, C., Jönsson, B., Pochard, I., Nonat, A. & Cabane, B. Surface charge density and electrokinetic potential of highly charged minerals: experiments and monte carlo simulations on calcium silicate hydrate. J. Phys. Chem. B 110, 9219–9230 (2006).

Zhang, J. S., Zhang, X., Zhang, Z. L. & Tan, Z. J. Potential of mean force between oppositely charged nanoparticles: a comprehensive comparison between Poisson-Boltzmann theory and Monte Carlo simulations. Sci. Rep. 7, 14145 (2017).

Li, Y., Dong, H.-L., Zhang, J.-S., Lin, C. & Tan, Z.-J. Effective repulsion between oppositely charged particles in symmetrical multivalent salt solutions: effect of salt valence. Front. Phys. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphy.2021.696104 (2021).

Bjøntegaard, Ø. & Sellevold, E. J. Interaction between thermal dilation and autogenous deformation in high performance concrete. Mater. Struct. 34, 266–272 (2001).

Lu, T., Li, Z. & Huang, H. Effect of supplementary materials on the autogenous shrinkage of cement paste. Materials 13, 1–15 (2020).

Wagner, M. et al. Gypsum formation mechanisms and their contribution to crystallisation pressure in sulfate resistant hardened cement pastes during early external sulfate attack at low sulfate concentrations. Cem. Concr. Res. 168, 107138 (2023).

Powers, T. C. Structure and physical properties of hardened portland cement paste. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 41, 1–6 (1958).

Scrivener, K., Martirena, F., Bishnoi, S. & Maity, S. Calcined clay limestone cements (LC3). Cem. Concr. Res. 114, 49–56 (2018).

Li, X., Dengler, J. & Hesse, C. Reducing clinker factor in limestone calcined clay-slag cement using C-S-H seeding – A way towards sustainable binder. Cem. Concr. Res. 168, 107151 (2023).

Li, X. et al. Reactivity tests for supplementary cementitious materials: RILEM TC 267-TRM phase 1. Mater. Struct. 51, 151 (2018).

Shanahan, N. & Zayed, A. Cement composition and sulfate attack: Part I. Cem. Concr. Res. 37, 618–623 (2007).

(CEN), E. C. f. S. In European Committee For Standardisation (2011).

Grassl, H., Dengler, J., Schoebel, A., Albrecht, G. & Pulkin, M. Set control composition for cementitious systems. WO 2019/077050 A1 (2018).

Grassl, H., Dengler, J., Mussner, R. & Szentmiklosi, Z. Construction material composition having high early and late strength. WO 2023/025585 (2021).

EN, T. 196-1. Methods of testing cement–Part 1: determination of strength. European Committee for Standardization. Vol. 26 (2005).

Vollpracht, A., Lothenbach, B., Snellings, R. & Haufe, J. The pore solution of blended cements: a review. Mater. Struct. 49, 3341–3367 (2016).

Caruso, F., Mantellato, S., Palacios, M. & Flatt, R. J. ICP-OES method for the characterization of cement pore solutions and their modification by polycarboxylate-based superplasticizers. Cem. Concr. Res. 91, 52–60 (2017).

Li, X., Snellings, R. & Scrivener, K. L. Quantification of amorphous siliceous fly ash in hydrated blended cement pastes by X-ray powder diffraction. J. Appl. Crystallogr. https://doi.org/10.1107/S1600576719013955 (2019).

Li, X., Bizzozero, J. & Hesse, C. Impact of C-S-H seeding on the hydration of slag blended cement. Cem. Concr. Res. 161, 106935 (2022).

Scrivener, K., Snellings, R. & Lothenbach, B. A Practical Guide to Microstructural Analysis of Cementitious Materials (CRC Press, 2018).

Bizzozero, J., Gosselin, C. & Scrivener, K. L. Expansion mechanisms in calcium aluminate and sulfoaluminate systems with calcium sulfate. Cem. Concr. Res. 56, 190–202 (2014).

Kulik, D. A. et al. GEM-Selektor geochemical modeling package: revised algorithm and GEMS3K numerical kernel for coupled simulation codes. Comput. Geosci. 17, 1–24 (2013).

Lothenbach, B. et al. Cemdata18: a chemical thermodynamic database for hydrated Portland cements and alkali-activated materials. Cem. Concr. Res. 115, 472–506 (2019).

Berodier, E., Bizzozero, J. & Muller, A. C. In A Practical Guide to Microstructural Analysis of Cementitious Materials (eds Scrivener K., Snellings R., & Lothenbach B.) Ch. 9, (CRC Press, 2018).

BASF. BASF Calculates CO2 Footprint Of All Sales Products. https://www.basf.com/global/en/media/news-releases/2020/07/p-20-260.html (2020).

BASF. Product Carbon Footprint. https://www.basf.com/global/en/who-we-are/sustainability/we-drive-sustainable-solutions/quantifying-sustainability/product-carbon-footprint.html (2023).

Scrivener, K., Sofia, L. & Avet, F. Concrete performance of limestone calcined clay cement (lc3) compared with conventional cements. Adv. Civil Eng. Mater. 8, 20190052 (2019).

Team, R. C. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, 2021).

Wickham, H. et al. Welcome to the Tidyverse. J. Open Source Softw. 4, 1686 (2019).

Acknowledgements

Ms. Franziska Bichler, Mr. Bernhard Mayr, Ms. Cornelia Kronast and Mr. Zsolt Attila Szentmiklosi from BASF Construction Additives GmbH (BCA) are acknowledged for their contributions to the experimental study. Support from the team of colleagues at the analytical center at BCA was appreciated. Dr. Florian Deschner from BCA assisted with the GEMS modeling of the kinetic data. Comments from Dr. Nikolaus Nestle from BASF SE contributed to this paper. The support of Dr. Christian Trieflinger from BCA is acknowledged.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

X.L. and J.D. conceived and designed the experiments, drafted the article, and revised it. X.L. performed the data analysis. J.D., H.G. and C.H. developed the hydration control additive. All authors discussed and reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare the following financial interests/personal relationships which may be considered as potential competing interests: All authors are employees of BASF Construction Additives GmbH as of publication date of the work.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Materials thanks Carlos Fernandez and the other, anonymous, reviewer for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editor: John Plummer. A peer review file is available

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, X., Grassl, H., Hesse, C. et al. Unlocking the potential of ordinary Portland cement with hydration control additive enabling low-carbon building materials. Commun Mater 5, 1 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43246-023-00441-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43246-023-00441-9