Abstract

Solution-processed single-crystal organic semiconductors (OSCs) and amorphous metal oxide semiconductors (MOSs) are promising for high-mobility p- and n-channel thin-film transistors (TFTs), respectively. Organic−inorganic hybrid complementary circuits hence have great potential to satisfy practical requirements. However, some chemical incompatibilities between OSCs and MOSs, such as heat and chemical resistance, make it difficult to rationally integrate TFTs based on solution-processed OSC and MOS onto the same substrates. Here, we report a rational integration method based on the solution-processed semiconductors by carefully managing the device configuration and the deposition and patterning techniques from a materials point of view. The balanced high performances as well as the uniform fabrication of the TFTs led to densely integrated five-stage ring oscillators with a short propagation delay of 1.3 µs per stage.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Solution technique is of vital interest to both industry and academia for manufacturing electronic devices. To meet the requirements from low-cost and mass-producible electronics, such as printed electronics, Internet of Things (IoT) technology and Trillion Sensors Universe, solution techniques suitable for thin-film transistors (TFTs) on plastic substrates get more and more attention, where the solution-processed deposition of semiconductors is the primary subject. From engineering point of view, complementary circuits, which are constructed from the pairs of p- and n-channel TFTs, with high-mobility and performance-balanced p- and n-channel TFTs are preferred for actual devices such as radio-frequency identification tags and sensors because they can enable high operation speeds, low power dissipation, wide noise margin, and an easy and compact circuit design. For this aim, organic semiconductors (OSCs) are the most promising for the TFT applications owing to their solubility, low fabrication temperature and high compatibility with flexible substrates1. Thus far, OSC materials and solution techniques have been developed to facilitate the implementation of organic TFTs, particularly with single-aligned crystals or single crystals2,3,4,5,6,7,8, which could be beneficial for high electrical properties. Despite the advantages of complementary circuits, most of solution-processable and high-mobility OSCs predominantly behave as hole-transporting materials, thus providing p-channel TFTs. In other words, (so-called n-type) OSCs suitable for n-channel TFTs are still lagging behind p-type counterparts due to their anisotropic crystal packings and less effective electronic couplings due to the essential introduction of strong electron-withdrawing groups9. Meanwhile, thin films of amorphous metal oxide semiconductors (MOSs) can be also prepared by solution processes, such as the sol-gel method, and have been developed for n-channel TFTs10,11,12,13,14,15 because of their high electron mobility, excellent uniformity, and good ambient stability. By contrast to OSCs, MOSs are hardly useful for p-channel TFTs owing to the unfavourable hole formation as well as hole-transporting path due to the presence of highly occupied localised oxygen 2p orbitals16. Most of the reported circuits based on either only solution-processed OSCs or MOSs are hence designed by unipolar or pseudo-complementary operations17,18,19,20,21, or complementary circuits with an unsatisfactory performance22,23,24,25,26,27.

Therefore, the organic−inorganic hybrid system is one way to overcome such limitations as reported by using a vacuum process28,29,30,31. On the other hand, integrated circuits composed of solution-processed p-type OSC and n-type MOS32,33,34,35,36 need to overcome chemical issues during their integration into the same circuit. For instance, OSCs are self-assembled in the solid states via weak van der Waals forces, whereas MOSs are covalently bound, which leads to incompatible processing parameters, such as temperature, heat and chemical resistance, and adaptability to lithographic processes. Due to the curing conditions, MOSs are prepared in advance of OSC deposition, which often deteriorates the MOSs maybe due to organic solvent vapour and heat during the OSC deposition. In addition, fine patterning is mandatory in both semiconductors and electrodes to avoid crosstalk and realise high-speed operations, and the requirement of a high degree of integration for practical application affords further tasks; therefore, the complementary circuits based on solution-processed, high-performance OSC and MOS are challenging. Although a few solution-processed hybrid complementary circuits have been demonstrated with photolithographic processes, their TFT performances, such as mobility and on-off switching ratio, were compromised because of the low mobility of macromolecular OSCs and the chemical degradation of MOSs35,36. In other words, there were no rational and feasible methodologies to integrate solution-processed OSCs and MOSs into complementary circuits despite the very simple concept of hybridisation.

In this study, we demonstrate the hybrid complementary circuits composed of solution-processed high-performance semiconductors: single crystals of a small-molecule OSC, 3, 11-dinonyldinaphto[2, 3-d:2’, 3’-d’]benzo[1, 2-b:4, 5-b’]dithiophene (C9-DNBDT-NW), and amorphous indium zinc oxide (IZO) for p- and n-channel TFTs, respectively. They were selected because of their high carrier mobility, uniformity, and potential scalability7,37,38. Herein, the patterning and integration of solution-processed MOS- and OSC-based TFTs were carefully managed through the selection of materials and processes to suppress chemical and physical degradations due to solvents and heat for high-speed operations. In the following sections, we will describe our achievements based on the hybrid complementary inverters, which exhibit desirable switching properties and excellent long-term stability on a plastic substrate. Demonstration of five-stage complementary ring oscillators revealed the uniformity of both single-crystal C9-DNBDT-NW and amorphous IZO, and the short propagation delay of 1.3 μs per stage with an operation voltage of 10 V was achieved, indicating that the present facile method combining the advantages of solution-processed OSC and MOS can meet future IoT demands.

Results and discussion

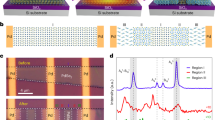

Integrated process

The hybrid complementary inverter on a polyimide (PI) substrate with C9-DNBDT-NW single crystals and amorphous IZO as the p- and n-channel material, respectively, is schematically illustrated in Fig. 1a. Both the p- and n-channel TFTs have bottom-gate top-contact structures. As illustrated in Fig. 1b, for the IZO-based n-channel TFT, gate electrodes were fabricated by photolithography and a lift-off process. Meanwhile, the AlOx gate dielectric layer was formed by atomic layer deposition (ALD). The IZO layer was deposited by spin coating and patterned via photolithography and wet-etching. To reduce the number of photolithography steps, source/drain (S/D) electrodes of n-channel TFTs and gate electrodes of p-channel TFTs were fabricated simultaneously. Then, polymethylmethacrylate (PMMA) and parylene were sequentially formed as a bilayer gate dielectric for p-channel TFTs and as a passivation layer for n-channel TFTs to protect the back-channel of IZO-based TFTs against potential damage during subsequent integration processes, where PMMA could protect IZO from undesired chemical reaction with the monomeric diradical intermediate of parylene39. C9-DNBDT-NW single-crystal was solution-crystallized by continuous edge casting method7,40 on a superhydrophilic nano-ground glass template. Then the template was placed on the target substrate with C9-DNBDT-NW facing PMMA/parylene dielectric layer. The C9-DNBDT-NW single-crystal was transferred from the template to the surface of parylene by being mediated by a few water droplets penetrated into the C9-DNBDT-NW/superhydrophilic template interface41.

A cross-polarised optical micrograph of C9-DNBDT-NW single crystals on the as-fabricated IZO-based TFTs before patterning revealed a clear crystal domain (Supplementary Fig. 1). Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) images of the cross-section of the C9-DNBDT-NW channel produced by focused ion beam (FIB) machining revealed burr-free gate electrodes of the p-channel TFT (Supplementary Fig. 2), which ensures the parylene surface smooth enough for transferring the C9-DNBDT-NW single crystal layer without undesired mechanical damages. OSC patterns and Au S/D electrodes were formed via a two-step patterning process, in which photosensitive dielectric materials (PDMs, a dry-film photoresist)/PMMA double sacrificial layers were employed for a damage-free patterning of OSC-based TFTs. As shown in Supplementary Fig. 3, PDM (the top layer) enables the formation of the OSC and S/D patterns while PMMA facilitated the stripping of the resist with acetonitrile, thus causing little damage to the OSC. The PDM was laminated on the substrate and patterned by photolithography42,43, while the PMMA layer was deposited via spin coating and etched with O2 plasma. Furthermore, the PDM contributed to the damage-free fabrication of OSC-based TFTs as the solvent content in the dry film was <2 wt.% and the PDM patterning process is based on the polymerization of double bonds rather than the generation of photoacids. Therefore, the potential damage induced by solvents or acids in conventional photolithography could be eliminated effectively. The contact resistance (Rc) of C9-DNBDT-NW-based TFTs fabricated by this technology was studied using the transfer-line method, as described in the Supporting Information (Supplementary Note 1). The intrinsic mobility (µint) of C9-DNBDT-NW TFTs was ~10 cm2 V−1 s−1 and the normalised contact resistance (RcW) was ~230 Ω cm (Supplementary Fig. 4), which is comparable to our previous work on a monolayer C9-DNBDT-NW-based TFT44.

Electrical performance of the hybrid inverters

A micrograph of a complementary inverter is shown in the inset of Fig. 2a. The output curves revealed that both the n- and p-channel TFTs exhibited a typical output with good pinch-off behaviour and negligible hysteresis (Fig. 2a). The transfer characteristics of each TFT in the linear and saturation regions are illustrated in Fig. 2b–e. In the case of C9-DNBDT-NW-based TFTs, transfer curves in the linear (Fig. 2b) and saturation (Fig. 2d) regions indicated the linear and saturation mobilities (µlin and µsat, respectively), on-off current ratio (Ion/Ioff), off current (Ioff), and turn-on voltage (Von) of 5.8 and 5.1 cm2 V−1 s−1, 108, 10−12 A, and ~2 V, respectively; the corresponding values in the IZO TFT were 2.9 and 4.0 cm2 V−1 s−1, 108, 10−12 A and ~0 V, respectively (Fig. 2c, e).

Due to contact resistance, the effective mobility (µeff) is lower than µint, especially in short-channel devices, as shown in Eq. (1),

where Ci is the gate capacitance per unit area, VG represents gate voltage, and Vth is the threshold voltage. The µeff of the C9-DNBDT-NW-based TFT was estimated to be ~5.9 cm2 V−1 s−1, which is similar to the experimental value. In the case of the IZO-based TFT, RcW was estimated to be 29 Ω cm and the effective resistance measured after the integration process is at similar to that of IZO TFTs before integration38. The good performance of C9-DNBDT-NW- and IZO-based TFTs can be attributed to the high performance of the semiconductor materials and the well-designed integration processes. Patterned gate electrodes and short channels lead to degraded performance45, especially in TFTs with bottom-gate top-contact structures. This may be because (1) as the channel length decreases, contact resistance starts to dominate, (2) the S/D patterning process may damage the semiconductor layer, and (3) the uneven surface caused by patterned gate electrodes may affect the uniformity of the active layer in the solution-processed semiconducting thin film. In this study, these problems were solved by using damage-free processes for both p- and n-channel TFTs, controlling the thickness and edge conditions of the gate electrode, and excluding the damage from further p-channel TFT integration process on IZO-based TFTs, which was processed with a bilayer PMMA/parylene passivation structure.

The hybrid complementary inverter exhibited the full rail-to-rail output swing and negligible hysteresis (Fig. 3a, b). The corresponding voltage gain and static current (Isupply) values are shown in Fig. 3c, d, respectively. At a VDD of 7 V, a nearly symmetrical voltage transfer curve (VTC) with a midpoint voltage (VM) of 3.42 V and maximum voltage gain of 38 V/V was observed. Isupply was 1 × 10−9 A at Vin = 0 V while Isupply was on the order of 10−7 A at high Vin (Fig. 3d), where the static power consumption was still <0.76 μW at VDD = 7 V, for example. The higher static Isupply at high Vin was due to higher ID of the p-channel TFT at VG = 0 V or Vin = 7 V than that of the n-channel TFT at VG = 0 V or Vin = 0 V by 5 orders of magnitude (3 × 10−7 and 1 × 10−12 A, respectively) (Supplementary Figure 5). Our future work will aim to control Von for p-channel TFTs to further lower the static power consumption of complementary inverters. Figure 3e shows the VTC obtained with a VDD of 7 V; the noise margins high (NMH) and noise margin low (NML) are indicated by green rectangles (NMH = 2.7 V and NML = 1.9 V).

It is particularly important to note that the hybrid complementary inverter exhibited a decent performance even after exposure to the ambient atmosphere (air) for 5 months (Fig. 3f), whereas the off current slightly increased in both TFTs (Supplementary Fig. 6). This may be attributed to a self-healing effect in which the number of carrier traps decreased slightly over time6,46. Besides, Von of the IZO TFT slightly shifted, which would be due to the diffusion of environmental molecules such as oxygen and water because the current passivation layer, PMMA/parylene, could not isolate the device completely39. The passivation technique is being studied to further stabilise these devices.

Flexibility of the hybrid inverters

The PI substrate was delaminated from the glass support using a laser lift-off (LLO) method to evaluate the flexibility of the as-fabricated inverters. Figure 4a shows a photograph of the circuits on a free-standing PI film and Fig. 4b compares the VTCs obtained before and after delamination at VDD = 4, 6, 8, and 10 V. The overlap between the VTCs at each VDD indicated that the LLO process did not adversely affect the electrical performance of the inverter.

The bending stress test was carried out by measuring VTCs by laminating the PI film devices onto the cylindrical surfaces (Fig. 5a, b). With various bending radii (17.5, 12.0, and 6.0 mm), no significant changes were observed. As shown in Fig. 5c–f, both the p- and n-channel TFTs exhibited decent transfer characteristics under the action of a bending stress. The slight Von shift is probably due to system error during measurement38,47. The bending stress applied on semiconductors depends not only on the bending radii but also device structure and substrate thickness. The corresponding surface strain (ε) can be calculated using the following equation45

where R is the bending radius and hs is substrate thickness. In principle, when a substrate is bent, there is always a layer with zero bending stress and while the inner surface suffers compression stress, the outer surface suffers tensile stress. In this study, compared with the thickness of PI substrates (~10 µm), the total thickness of the other layers (<500 nm) was much less; hence, the TFTs experienced a tensile force perpendicular to the channels. In other words, the tensile force was applied in the c-axis direction, i.e., the preferred carrier-transport direction in the herringbone packing structure of the C9-DNBDT-NW single crystal, which might decrease carrier mobility48. Meanwhile, amorphous IZO was isotopically stressed. Using Eq. (2), the maximum tensile stress was estimated to be 0.08% with a bending radius of 6 mm, at which the decrease in mobility was small (1%)48; this observation is consistent with our results. In addition, the small tensile stress should have negligible effects on the amorphous IZO layer. Therefore, the identical electrical performance of the inverter under bending conditions suggests that this hybrid technology can enrich flexible electronic applications.

a Schematic illustration of a device under bending stress. b VTCs of the inverter when flat and bent to tensile radii of 17.5, 12.0, and 6 mm. The inset shows the measurement setup with a bending radius of 6 mm. Transfer curves of TFTs based on (c and d) C9-DNBDT-NW (W/L = 100 μm/19 μm) and (e and f) IZO (W/L = 50 μm/24 μm) in the linear and saturation regions under different bending stresses.

Performance of hybrid ring oscillators

Unlike direct calculation by propagation delay, ring oscillators provide a simple and effective way to evaluate the maximum switching speed of larger logic gates. In a ring oscillator, each inverter delays the input signal for a specific time, which is defined as the stage propagation delay (tp). To simplify, we assume that all inverters have the same property and the same delay time. The delay time at the output can hence be written as

where n is the stage number and T is the period of the ring oscillator. By measuring the operation frequency of the ring oscillator (fROSC), tp can be calculated as shown in Eq. (4).

Five-stage ring oscillators were fabricated by connecting five inverters in a loop to study the propagation delay of the hybrid inverter and the availability of more complex circuits. An optical micrograph of the as-fabricated ring oscillator is shown in Fig. 6a. In each stage, the dimensions were W/L = 200 μm/4 μm and ΔL = 3 μm for the p-channel TFT and W/L = 200 μm/8 μm and ΔL = 1.5 μm for the n-channel TFT, where ΔL is the gate overlap with each source and drain electrode. The electrical performance of the p- and n-channel TFTs recorded under these conditions is shown in Supplementary Fig. 7. The p-channel TFT exhibited µlin and µsat, Ioff, and Ion/Ioff ratio of 4.4 and 1.1 cm2 V−1 s−1, 10−13 A, and 108, respectively, while the corresponding values for the n-channel TFT were 1.6 and 1.9 cm2 V−1 s−1, 10−13 A, and 109 respectively. Note that, for the p-channel TFT, µsat value was smaller than µlin due to an early saturation phenomenon, which has been recently observed in the short-channel, single-crystal OSC-based TFTs and could be attributed to velocity saturation effect, thermal damage during depositing Au and/or the interface diode effect49,50.

a Optical micrograph of a hybrid ring oscillator. The magnified image shows one stage. W/L = 200 µm/4 µm and ΔL = 3 µm for p-channel TFT and W/L = 200 µm/8 µm and ΔL = 1.5 µm for n-channel TFT, where ΔL is the gate overlap. b VTCs of the hybrid inverter with VDD = 10 V. c Output signal of the ring oscillator at VDD = 10 V.

The VTC of a single inverter (Fig. 6b) suggests that even those inverters with short channel lengths exhibit a full rail-to-rail swing, symmetric transition of VM \(\sim\) 5 V for both forward and backward voltage sweep, and a high noise margin with an NMH of 3.2 V and NML of 2.9 V. The output signal from the five-stage ring oscillator at a VDD of 10 V is shown in Fig. 6c. In this case, fROSC was 77 kHz and thus tp was estimated to be 1.3 µs. We compared several complementary ring oscillators based on solution-processed OSCs or MOSs with respect to tp (Table 1). As there are only a few studies on plastic substrates, ring oscillators fabricated on rigid substrates were also considered. Because fROSC is approximately proportional to VDD51, different devices were compared by converting VDD to 10 V and the corresponding tp after conversion is defined as tp(10V). Notably, the present tp(10V) lies among the smallest values achieved by solution-processed p- and n-type semiconductors, which underlines the advantage of hybrid complementary circuits based on single-crystal OSC and amorphous MOS. In addition, our circuits can work on flexible, plastic substrates, which is an advantage beyond ref. 45 demonstrated using a glass substrate due to the necessity of an annealing process at 500 °C. As shown in Supplementary Fig. 8, the complementary ring oscillators with different dimensions were fabricated over the substrate. Considering fROSC with different TFT dimensions, fROSC in the current devices was principally dominated by L but subsequently by ΔL. Hence, the future task for increasing fROSC may include an improved technology of fine patterning, where the reduction of contact resistance should get required for advanced performances.

Conclusion

We have demonstrated organic−inorganic hybrid complementary circuits on plastic substrates by using solution-processed, high-performance semiconductors: p-type C9-DNBDT-NW single crystals and n-type amorphous IZO. Owing to their high carrier mobilities and air stability, the TFTs and the complementary inverters exhibited excellent electrical characteristics and long-term stability, and the five-stage complementary ring oscillator operated at 77 kHz with a supply voltage of 10 V in air, proving the likeliest approach to high-speed complementary circuits based on the solution-processed semiconductors. Although solution-processed amorphous MOSs are usually sensitive to chemical species such as water and organic solvents, the reliable integration of the OSC-based TFTs with the pre-fabricated MOS-based TFTs shown in this paper can be attributed to the following materials viewpoints: (1) An effective protection bilayer for IZO based on a PMMA underlayer, which is solution-processable at low temperature and chemically harmless for IZO, and acts as a barrier of the undesired reaction between IZO and the diradical parylene intermediate during the formation of upper layer; (2) Water-based transferring integration of solution-coated OSC thin films with the pre-fabricated IZO-based TFTs with the help of hydrophobic parylene layer; (3) Damage-free photolithographic processes using the dry-film, photoacid-free photoresist. The scalability of current solution-coating methods can promise further developments of the high-speed complementary circuits for IoT applications, where it is required to reduce the contact resistance and to minimise the channel dimensions and capacitive parasitism, which needs the help of materials science.

Methods

Substrate preparation

All the devices used in this study were fabricated on PI substrates. The PI substrate was prepared by spin-coating polyamic acid (Ube Industries, Ltd.) on a glass supporter (5 × 5 cm2) at 2000 rpm for 3 min, followed by thermal curing at 110 °C for 60 min, 150 °C for 30 min, 200 °C for 10 min, 250 °C for 10 min, and 430 °C for 10 min on a hot plate in the air. The PI film was attached to a glass support during fabrication and delaminated using an LLO technique to achieve free-standing films for flexibility evaluation.

Fabrication of n-channel TFTs based on IZO

IZO films were fabricated using a sol-gel method. Initially, In and Zn precursor solutions (0.1 M) were prepared by adding In(NO3)3·xH2O (Aldrich) and Zn(NO3)2·xH2O (Aldrich) to 2-methoxyethanol, respectively, and stirring at room temperature in the air for more than 6 h. The IZO precursor was then prepared by mixing the In and Zn precursors at an In/Zn ratio of 3/2 and stirring under the conditions described above.

Both n- and p-channel TFTs exhibit a bottom-gate top-contact structure. Gate patterns of IZO-based TFTs were formed by photolithography with a photoresist (TLOR, Tokyo Ohka Kogyo Co., Ltd.). Cr/Au/Cr (5/25/5 nm) was deposited via thermal evaporation, followed by a lift-off process. An AlOx gate dielectric layer was formed by ALD. Before IZO deposition, the substrate was treated with a UV ozone cleaner (Filgen, Inc., UV253H) for 10 min to remove any organic residues and improve its wettability. The IZO precursor was then spin-coated on the substrate at 500 rpm for 5 s and 5000 rpm for 30 s, followed by soft baking at 150 °C for 5 min and hard baking at 370 °C for 1 h under ambient conditions. The IZO film was patterned with a PDM (Taiyo Ink Mgf. Co., Ltd.), and etched with oxalic acid. S/D electrodes for IZO-based TFTs and gate electrodes for C9-DNBDT-NW-based TFTs (Al, 45 nm) were deposited by thermal evaporation and patterned by a lift-off process based on PDM38.

Fabrication of p-channel TFTs based on C9-DNBDT-NW

After the fabrication of n-channel TFTs, a PMMA/parylene bilayer was fabricated to act as a passivation layer for n-channel TFTs and it doubled as a gate dielectric for p-channel TFTs. The PMMA layer was formed by spin coating a PMMA solution (Mw = 120,000, 0.56 wt.% in butyl acetate) at 500 rpm for 5 s and then 4000 rpm for 30 s, followed by soft baking at 150 °C for 1 h. The parylene layer was deposited by chemical vapour deposition.

C9-DNBDT-NW was synthesised and purified in-house; initially, a C9-DNBDT-NW solution was prepared by dissolving 0.02 wt.% C9-DNBDT-NW in 3-chlorothiophene. The C9-DNBDT-NW single-crystal layer was once formed by continuous edge casting on a super hydrophilic substrate and then transferred to the top of the PMMA/parylene dielectric layer. More details can be found in our previous reports7,40,41.

Fine patterns of OSC and Au S/D electrodes were achieved by a two-step patterning process based on a dry film resist with a thickness of 5 µm (PDM, Taiyo Ink Mfg. Co., Ltd.)42,43. This process is illustrated schematically in Supplementary Figure 9. A PMMA layer (Mw = 120,000, 5 wt.% in butyl acetate) was formed by spin coating at 500 rpm for 5 s and 1000 rpm for 30 s, followed by baking at 80 °C for 10 min before being laminated with a PDM dry film. The PDM layer was patterned by photolithography and PMMA was patterned using O2 plasma with patterned PDM as a mask. After etching the OSC or S/D electrodes, PMMA and PDM were stripped together with acetonitrile. For OSC patterning, Au (30 nm) was deposited via thermal evaporation on the entire surface and it acted as a protection layer as well as S/D electrodes. Subsequently, a two-step photolithography process was conducted. Au was etched using an AURUM S-50790 (Kanto Chemical Co. Inc.) instrument and the OSC layer was etched using O2 plasma. Subsequently, a solid-state laser (Delphi Laser, Inducer-6001-P, 355 nm) was used to create holes in the gate dielectrics for bottom electrodes. Next, Au (60 nm) was deposited by thermal evaporation and patterned by two-step photolithography to form S/D electrodes and conduction terminals for the bottom electrodes. Finally, the substrate was annealed at 110 °C for 1 h to remove the solvent used during fabrication.

Device characterisation

The electrical properties of the fabricated hybrid inverters were measured under ambient and dark conditions. The static properties of the TFTs and the VTCs of the inverters were measured using a semiconductor parameter analyser (Keithley, 4200-SCS). The output signals of the ring oscillators were recorded using an oscilloscope (Tektronix, MDO3014). Micrographs of the complementary inverter and ring oscillator were acquired using an optical microscope. An FIB-SEM (JEOL, JIB-4700F) was used to observe the edge conditions of the gate electrodes in p-channel TFTs.

Carrier mobility (µ) and Vth were determined by measuring the dependence of drain current (ID) on VG and fitting with the following equations.

In the linear region,

In the saturation region,

Ci is determined by capacitance–voltage measurements at 10 kHz. The values of Ci for the ring oscillators used in this study were 88.5 nF cm–2 for n-channel (AlOx, 80 nm) and 13.2 nF cm–2 for p-channel (PMMA, ~10 nm; parylene, ~190 nm); for inverters discussed in other parts (excepted the ring oscillators, Fig. 6 and Supplementary Figs. 7–8) 122.5 nF cm–2 for n-channel (AlOx, 63 nm) and 22.1 nF cm–2 for p-channel (PMMA, ~10 nm; parylene, ~120 nm).

Data availability

All the data are available within this article and its Supplementary Information, as well as from the corresponding author upon request.

References

Chang, J. S., Facchetti, A. F. & Reuss, R. A circuits and systems perspective of organic/printed electronics: review, challenges, and contemporary and emerging design approaches. IEEE Trans. Emerg. Sel. Topics Circuits Syst. 7, 7–26 (2017).

Minemawari, H. et al. Inkjet printing of single-crystal films. Nature 475, 364–367 (2011).

Diao, Y. et al. Solution coating of large-area organic semiconductor thin films with aligned single-crystalline domains. Nat. Mater. 12, 665–671 (2013).

Arai, S., Inoue, S., Hamai, T., Kumai, R. & Hasegawa, T. Semiconductive single molecular bilayers realized using geometrical frustration. Adv. Mater. 30, 1707256 (2018).

Peng, B., Wang, Z. & Chan, P. K. L. A simulation-assisted solution-processing method for a large-area, high-performance C10-DNTT organic semiconductor crystal. J. Mater. Chem. C 4, 8628–8633 (2016).

Yamamura, A. et al. Wafer-scale, layer-controlled organic single crystals for high-speed circuit operation. Sci. Adv. 4, eaao5758 (2018).

Kumagai, S. et al. Scalable fabrication of organic single-crystalline wafers for reproducible TFT arrays. Sci. Rep. 9, 15897 (2019).

Duan, S. et al. Solution-processed centimeter-scale highly aligned organic crystalline arrays for high-performance organic field-effect transistors. Adv. Mater. 32, 1908388 (2020).

Okamoto, T. et al. Robust, high-performance n-type organic semiconductors. Sci. Adv. 6, eaaz0632 (2020).

Thomas, S. R., Pattanasattayavong, P. & Anthopoulos, T. D. Solution-processable metal oxide semiconductors for thin-film transistor applications. Chem. Soc. Rev. 42, 6910–6923 (2013).

Fortunato, E., Barquinha, P. & Martins, R. Oxide semiconductor thin-film transistors: a review of recent advances. Adv. Mater. 24, 2945–2986 (2012).

Banger, K. K. et al. Low-temperature, high-performance solution-processed metal oxide thin-film transistors formed by a ‘sol-gel on chip’ process. Nat. Mater. 10, 45–50 (2011).

Kim, M. G., Kanatzidis, M. G., Facchetti, A. & Marks, T. J. Low-temperature fabrication of high-performance metal oxide thin-film electronics via combustion processing. Nat. Mater. 10, 382–388 (2011).

Kim, Y.-H. et al. Flexible metal-oxide devices made by room-temperature photochemical activation of sol-gel films. Nature 489, 128–132 (2012).

Ong, B. S., Li, C., Li, Y., Wu, Y. & Loutfy, R. Stable, solution-processed, high-mobility ZnO thin-film transistors. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 129, 2750–2751 (2007).

Hosono, H. Ionic amorphous oxide semiconductors: material design, carrier transport, and device application. J. Non-Cryst. Solids 352, 851–858 (2006).

Shiwaku, R. et al. Printed 2 V-operating organic inverter arrays employing a small- molecule/polymer blend. Sci. Rep. 6, 34723 (2016).

Shiwaku, R. et al. Printed organic inverter circuits with ultralow operating voltages. Adv. Electron. Mater. 3, 1600557 (2017).

Watson, C. P., Brown, B. A., Carter, J., Morgan, J. & Taylor, D. M. Organic ring oscillators with sub-200 ns stage delay based on a solution-processed p-type semiconductor blend. Adv. Electron. Mater. 2, 1500322 (2016).

Kim, K. H., Kim, Y.-H., Kim, H. J., Han, J.-I. & Park, S. K. Fast and stable solution-processed transparent oxide thin-film transistor circuits. IEEE Electron Device Lett. 32, 524–526 (2011).

He, G., Li, W., Sun, Z., Zhang, M. & Chen, X. Potential solution-induced HfAlO dielectrics and their applications in low-voltage-operating transistors and high-gain inverters. RSC Adv. 8, 36584–36595 (2018).

Baeg, K.-J. et al. High speeds complementary integrated circuits fabricated with all-printed polymeric semiconductors. J. Polym. Sci. Part B: Polym. Phys. 49, 62–67 (2011).

Kim, S. H., Lee, S. H., Kim, Y. G. & Jang, J. Ink-jet-printed organic thin-film transistors for low-voltage-driven CMOS circuits with solution-processed AlOx gate insulator. IEEE Electron Device Lett. 34, 307–309 (2013).

Takeda, Y. et al. Fabrication of ultra-thin printed organic TFT CMOS logic circuits optimized for low-voltage wearable sensor applications. Sci. Rep. 6, 25714 (2016).

Yamamura, A. et al. Painting integrated complementary logic circuits for single-crystal organic transistors: a demonstration of a digital wireless communication sensing tag. Adv. Electron. Mater. 3, 1600456 (2017).

Uno, M. et al. Short-channel solution-processed organic semiconductor transistors and their application in high-speed organic complementary circuits and organic rectifiers. Adv. Electron. Mater. 1, 1500178 (2015).

Chen, C., Yang, Q., Chen, G., Chen, H. & Guo, T. Solution-processed oxide complementary inverter via laser annealing and inkjet printing. IEEE Trans. Electron Devices 66, 4888–4893 (2019).

Rockelé, M. et al. Low-temperature and scalable complementary thin-film technology based on solution-processed metal oxide n-TFTs and pentacene p-TFTs. Org. Electron. 12, 1909–1913 (2011).

Myny, K. et al. Bidirectional communication in an HF hybrid organic/solution-processed metal-oxide RFID tag. IEEE Trans. Electron. Devices 61, 2387–2393 (2014).

Chen, H., Cao, Y., Zhang, J. & Zhou, C. Large-scale complementary microelectronics using hybrid integration of carbon nanotubes and IGZO thin-film transistors. Nat. Commun. 5, 4097 (2014).

Honda, W., Arie, T., Akita, S. & Takei, K. Bendable CMOS digital and analog circuits monolithically integrated with a temperature sensor. Adv. Mater. Technol. 1, 1600058 (2016).

Kim, K.-T. et al. A site-specific charge carrier control in monolithic integrated amorphous oxide semiconductors and circuits with locally induced optical-doping process. Adv. Funct. Mater. 29, 1904770 (2019).

Kim, K.-T. et al. An ultra-flexible solution-processed metal-oxide/carbon nanotube complementary circuit amplifier with highly reliable electrical and mechanical stability. Adv. Electron. Mater. 6, 1900845 (2020).

Hong, K. et al. Aerosol jet printed, sub-2 V complementary circuits constructed from p- and n-type electrolyte gated transistors. Adv. Mater. 26, 7032–7037 (2014).

Pecunia, V., Banger, K., Sou, A. & Sirringhaus, H. Solution-based self-aligned hybrid organic/metal-oxide complementary logic with megahertz operation. Org. Electron. 21, 177–183 (2015).

Pecunia, V. et al. Trap healing for high-performance low-voltage polymer transistors and solution-based analog amplifiers on foil. Adv. Mater. 29, 1606938 (2017).

Mitsui, C. et al. High-performance solution-processable N-shaped organic semiconducting materials with stabilized crystal phase. Adv. Mater. 26, 4546–4551 (2014).

Wei, X. et al. Solution-processed flexible metal-oxide thin-film transistors operating beyond 20 MHz. Flex. Print. Electron. 5, 015003 (2020).

Wei, X., Kumagai, S., Sasaki, M., Watanabe, S. & Takeya, J. Stabilizing solution-processed metal oxide thin-film transistors via trilayer organic–inorganic hybrid passivation. AIP Adv. 11, 035027 (2021).

Soeda, J. et al. Inch-size solution-processed single-crystalline films of high-mobility organic semiconductors. Appl. Phys. Express 6, 076503 (2013).

Makita, T. et al. High-performance, semiconducting membrane composed of ultrathin, single-crystal organic semiconductors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 117, 80–85 (2020).

Wei, X. & Shibasaki, Y. A novel photosensitive dry-film dielectric material for high density package substrate, interposer and wafer level package. in 2016 IEEE 66th Electronic Components and Technology Conference (ECTC) 159–164 (2016).

Okamoto, D., Shibasaki, Y., Shibata, D. & Hanada, T. New photosensitive dielectric material for high-density RDL with ultra-small photo-vias and high reliability. in 2018 51st International Symposium on Microelectronics (IMAPS) 2018, 000466–000469 (2018).

Makita, T. et al. Damage-free metal electrode transfer to monolayer organic single crystalline thin films. Sci. Rep. 10, 4702 (2020).

Kim, B. et al. High-speed, inkjet-printed carbon nanotube/zinc tin oxide hybrid complementary ring oscillators. Nano Lett. 14, 3683–3687 (2014).

Uemura, T. et al. On the extraction of charge carrier mobility in high-mobility organic transistors. Adv. Mater. 28, 151–155 (2016).

Watanabe, S. et al. Surface doping of organic single-crystal semiconductors to produce strain-sensitive conductive nanosheets. Adv. Sci. 8, 2002065 (2021).

Kubo, T. et al. Suppressing molecular vibrations in organic semiconductors by inducing strain. Nat. Commun. 7, 11156 (2016).

Peng, B. et al. Crystallized monolayer semiconductor for ohmic contact resistance, high intrinsic gain, and high current density. Adv. Mater. 32, 2002281 (2020).

Chen, M., Peng, B., Sporea, R. A., Podzorov, V. & Chan, P. K. L. The origin of low contact resistance in monolayer organic field-effect transistors with van der Waals electrodes. Small Sci. 2, 2100115 (2022).

Biabanifard, S., Largani, S. M. H. & Asadi, S. Delay time analysis of combined CMOS ring oscillator. ELELIJ 4, 53–64 (2015).

Kempa, H. et al. Complementary ring oscillator exclusively prepared by means of gravure and flexographic printing. IEEE Trans. Electron Devices 58, 2765–2769 (2011).

Smaal, W. et al. Complementary integrated circuits on plastic foil using inkjet printed n- and p-type organic semiconductors: fabrication, characterization, and circuit analysis. Org. Electron. 13, 1686–1692 (2012).

Baeg, K.-J. et al. Low-voltage, high speed inkjet-printed flexible complementary polymer electronic circuits. Org. Electron. 14, 1407–1418 (2013).

Mandal, S. et al. Fully-printed, all-polymer, bendable and highly transparent complementary logic circuits. Org. Electron. 20, 132–141 (2015).

Herlogsson, L., Crispin, X., Tierney, S. & Berggren, M. Polyelectrolyte-gated organic complementary circuits operating at low power and voltage. Adv. Mater. 23, 4684–4689 (2011).

Takeda, Y. et al. High-speed complementary integrated circuit with a stacked structure using fine electrodes formed by reverse offset printing. ACS Appl. Electron. Mater. 2, 763–768 (2020).

Takeda, Y. et al. Printed organic complementary inverter with single SAM process using a p-type D-A Polymer semiconductor. Appl. Sci. 8, 1331 (2018).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.T. and S.W. conceived the study. X.W. designed the integration process, carried out device fabrication, characterisation studies and the related data analysis, and wrote the first draft. S. K. contributed to the process design and data analysis of metal-oxide semiconductors and the passivation process. T.M. contributed to the fabrication and patterning of organic semiconductors. K.T. discussed the IZO preparation process. A.Y. and M.S. contributed to the design of complementary circuits. All authors analysed and interpreted the data and wrote the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

S.W. is an Editorial Board Member for Communications Materials and was not involved in the editorial review, or the decision to publish, this Article. All the other authors have no competing interests to declare.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Materials thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editor: John Plummer. Peer reviewer reports are available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wei, X., Kumagai, S., Makita, T. et al. High-speed hybrid complementary ring oscillators based on solution-processed organic and amorphous metal oxide semiconductors. Commun Mater 4, 4 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43246-023-00331-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43246-023-00331-0