Abstract

When a topological insulator is made into a nanowire, the interplay between topology and size quantization gives rise to peculiar one-dimensional states whose energy dispersion can be manipulated by external fields. In the presence of proximity-induced superconductivity, these 1D states offer a tunable platform for Majorana zero modes. While the existence of such peculiar 1D states has been experimentally confirmed, the realization of robust proximity-induced superconductivity in topological-insulator nanowires remains a challenge. Here, we report the realization of superconducting topological-insulator nanowires based on (Bi1−xSbx)2Te3 (BST) thin films. When two rectangular pads of palladium are deposited on a BST thin film with a separation of 100–200 nm, the BST beneath the pads is converted into a superconductor, leaving a nanowire of BST in-between. We found that the interface is epitaxial and has a high electronic transparency, leading to a robust superconductivity induced in the BST nanowire. Due to its suitable geometry for gate-tuning, this platform is promising for future studies of Majorana zero modes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The decisive characteristic of a topological insulator (TI) is the existence of gapless surface states whose gapless nature is protected by time-reversal symmetry. However, in a TI nanowire, the size quantization effect turns the topological surface states into peculiar one-dimensional (1D) states that are gapped due to the formation of subbands1,2. Interestingly, their energy dispersion can be manipulated by both magnetic and electric fields, and these tunable 1D states have been proposed to be a promising platform to host Majorana zero modes (MZMs) in the presence of proximity-induced superconductivity3,4. Therefore, realization of robust superconductivity in TI nanowires using the superconducting proximity effect is important for the future Majorana research. So far, the existence of the 1D subbands in TI nanowires has been probed by various means5,6,7,8,9,10,11, but it has been difficult to induce robust superconductivity in TI nanowires12, because a suitable method to realize an epitaxial interface between a TI nanowire and a superconductor has been lacking.

In terms of the realization of an epitaxial interface, it was previously reported13 that when Pd is sputter-deposited on a (Bi1−xSbx)2Te3 (BST) thin film, the diffusion of Pd into BST at room temperature results in a self-formation of PdTe2 superconductor (SC) in the top several quintuple-layers (QLs) of BST, leaving an epitaxial horizontal interface. Within the self-formed PdTe2 layer, Bi and Sb atoms remain as substitutional or intercalated impurities. This self-epitaxy was demonstrated to be useful for the fabrication of TI-based superconducting nanodevices involving planar Josephson junctions13. In such devices, the BST remains a continuous thin film and the superconducting PdTe2 proximitizes the surface states from above. In the present work, we found that depending on the Pd deposition method, Pd can diffuse deeper into the BST film and the conversion of BST into a PdTe2-based superconductor can take place in the whole film. Specifically, this full conversion occurs when Pd is thermally-deposited onto BST films with the thickness up to ~30 nm. This finding opened the possibility to create a TI nanowire sandwiched by SCs, by converting most of the BST film into the SC and leaving only a ~100-nm-wide BST channel to remain as the pristine TI. This way, one may induce robust superconductivity in the BST naowire proximitized by the PdTe2 superconductor on the side through an epitaxial interface.

Furthermore, this structure allows for gate-tuning of the chemical potential in the BST nanowire from both top and bottom sides (called dual-gating), which offers a great advantage to be able to independently control the overall carrier density and the internal electric field14. This is useful, because the realization of Majorana zero modes (MZMs) in a TI nanowire requires to lift the degeneracy of the quantum-confined subbands3,4, which can be achieved either by breaking time-reversal symmetry (by threading a magnetic flux along the nanowire)3 or by breaking inversion symmetry (by creating an internal electric field)4.

In this paper, we show that the devices consisting of BST nanowire sandwiched by PdTe2 superconductor indeed present robust proximity-induced superconductivity, evidenced by signatures of multiple Andreev reflections. Furthermore, in our experiment of the ac Josephson effect, we observed that the first Shapiro step is systematically missing at low rf frequency, low rf power, and at low temperature, which points to 4π-periodic current-phase relation and gives possible evidence for Majorana bound states. This result demonstrates that the superconducting TI nanowire realized here is a promising platform for future studies of MZMs.

Results

Nanowire formation

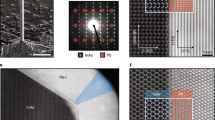

To confirm whether TI nanowires can indeed be created by Pd diffusion, we prepared BST/Pd bilayer samples specially designed for scanning transmission electron microscope (STEM) studies: a ~30-nm-thick BST film was epitaxially grown on an InP (111)A substrate and ~20-nm-thick rectangular Pd pads were thermally-deposited on BST with distances of ~200 nm between them. Figure 1a shows a high-angle annular-dark-field (HAADF) STEM image of the cross-section of such a sample; here, the two Pd pads are separated by 231.7 nm. The corresponding elemental maps of Pd, Bi, Sb and Te detected by energy-dispersive X-ray (EDX) spectroscopy (Fig. 1b–e) show that the Pd not only penetrates fully into the BST film beneath the pad, but also propagates outward by ~90 nm from each edge (Fig. 1b); note that in this sample, the outward diffusion was along the 〈110〉 direction (see Fig. 1e inset). As a result, a BST nanowire with a width of ~40 nm is left in-between the two Pd-containing regions. One can also see the swelling of Pd-absorbed BST (hereafter called Pd-BST) along the out-of-plane direction compared to the pristine BST region. We note that this STEM observation was made about 3 months after the Pd deposition, so that the in-plane Pd-diffusion length of ~90 nm is probably longer than that in devices that were measured soon after the Pd deposition. For additional STEM data for various Pd-pad separations, see Supplementary Note 1 and Supplementary Fig. 1.

a–e HAADF-STEM image and corresponding EDX spectroscopy maps of Pd, Bi, Sb and Te, respectively, of a cross-section of the Pd-BST/BST/Pd-BST heterojunction on InP substrate. The inset in panel e shows a plan-view SEM image of the Pd-pad array; the light-gray stripe depicts how the lamella specimen shown in panel a was cut out. f–h Atomic-resolution morphology of three locations in the specimen marked with green squares in the insets; the lattice image indicates the electron-beam incident direction of 〈100〉 or 〈110〉. i–k High-resolution HAADF image of PdTe2-like (i) and PdTe-like (k) structure of Pd-BST, together with schematic structural model and simulated HAADF image (thickness ~ 39 nm) to consider additional Pd atoms (green) intercalated into the PdTe2-like structure (j). In panel j, the atomic sites colored in blue, orange, and green may be occupied by Te/Bi/Sb, Pd/Sb, and Pd, respectively. Since the contrast of HAADF image is approximately proportional38 to square of the atomic number, Z2, one can see from the atomic contrast in panel i that Bi atoms are found only on the Te sites of the PdTe2 structure.

After confirming the creation of a TI nanowire, the next important question is the morphology of the system and identification of the converted phase. First, atomic-resolution examination of the TI nanowire region (Fig. 1f) confirms high-quality epitaxial growth of BST on the InP (111) surface, with QLs remain intact. Near the interface between BST and Pd-BST (Fig. 1g and Supplementary Fig. 2), one can see that the existence of Pd completely transforms QLs into a triple-layer (TL) structure characteristic of the PdTe2-like phase (Fig. 1i)13. Interestingly, the forefront of Pd-BST forms a V-shaped “epitaxial” interface to make a compromise between the different thicknesses of the QL and the TL. In the Pd-BST region closer to the Pd pad (Fig. 1h), we found that the TL structure changes to a zigzag pattern (Fig. 1k). Our image-simulation-based atomic structure analysis suggests that the TL- and zigzag-structured Pd-BST correspond to PdTe2-like and PdTe-like structural phases (Fig. 1j), respectively15. Depending on the concentration of Pd at different locations, the chemical formula may vary between Pd(Bi,Sb,Te)2 and Pd(Bi,Sb,Te), possibly with partial occupation of the Pd sites by Sb as well. Note that both PdTe2 and PdTe are SCs, with reported Tc of 2.0 and 4.5 K, respectively16,17. Our transport measurements show that Pd-BST is also a SC with Tc ≃ 1 K, which indicates that PdTe2 and PdTe still superconduct after heavy intercalation/substitution with Bi and Sb, albeit with a lower Tc.

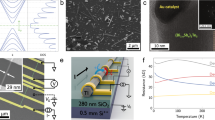

dc transport properties of the sandwich Josephson junction

To characterize how these TI nanowires are proximitized by the superconductivity in Pd-BST, we fabricated devices as shown in Fig. 2a in a false-color scanning electron microscope (SEM) image (for the transport characterization of the BST thin films used for device fabrication, see Supplementary Note 2 and Supplementary Fig. 3). These devices are SNS-type Josephson junctions (JJs) in which the TI nanowire is sandwiched by SCs. We can measure the supercurrent across the nanowire, but the 1D transport properties of the nanowire cannot be measured in these devices. Nevertheless, such a sandwich-JJ configuration allows us to quantitatively characterize the electronic transparency of the TI/SC interface. In the sample shown in Fig. 2a, the Pd pads to define the JJs had a width of 1 μm with the gap L systematically changed from 100 to 150 nm; therefore, the BST nanowires in the JJs were 1-μm long and less than 150-nm wide (with 30-nm thickness). The data we present here were obtained on the second junction from the left (device 1) in Fig. 2a. For shorter L, we obtained shorted junctions, while for longer L we obtained poor junctions with little or no supercurrent (see Supplementary Note 3 and Supplementary Fig. 4.).

a False-color SEM image of the wafer including device 1 (2nd left junction); Pd electrodes (dark-yellow), BST film (turquoise), and sapphire substrate (dark-blue) are visible. The five junctions pictured here were fabricated with the Pd gap ranging from 100 to 150 nm (from left to right). b T dependence of the critical current Ic of device 1 with a theoretical fit (red solid line), where the error bars are the larger of (i) the amplitude of the ac excitation current (±5 nA) or (ii) HWFM of the peak in dV/dI vs. Idc at the breakdown of superconductivity; inset shows the T dependence of the junction resistance measured with a quasi-four-terminal configuration. c dI/dV as a function of the dc bias voltage Vdc at various T; the curves are successively offset by 3.5 mS, except for the 20-mK data. Black arrows mark the MAR peaks with index n. Inset: The voltage corresponding to the MAR peaks, Vn, plotted vs. 1/n. d I–V characteristics at 20 mK in 0 T. A fit to the linear region at high bias (red dashed line) gives the excess current Ie and the normal-state resistance RN. Also, the IcRN product can be obtained from these data.

We note that there is an important difference between a planar junction, that is usually realized in TI-based JJs, and the sandwich junction realized here; namely, Andreev bound states (ABSs) are formed directly between the two TI/SC interfaces in the latter, while in the former, the superconducting part that is relevant to ABSs is not the SC above the TI surface but is the proximitized portion of the surface covered by the SC18,19. Even though planar junctions can have a large effective gap20,21, they are effectively SS’NS’S junctions where S’ can have a soft gap and/or be the source of additional in-gap states, whereas S’ can be minimized or even completely removed in sandwich junctions. In the junctions realized here, the top and bottom surfaces of our BST nanowire remain well-defined, which suggests that they each form a SNS junction with the N region containing the topological surface states as treated by Fu and Kane22. In such a line junction, one-dimensional Majorana bound states having a 4π-periodicity were predicted to show up, where time-reversal symmetry is broken due to the phase difference across the junction.

The junction resistance R of device 1 is plotted as a function of temperature T in the inset of Fig. 2b. The sharp drop in R at 1.16 K is due to the superconducting transition of Pd-BST. Zero resistance was observed only below ~0.65 K, but a sharp rise in voltage V in the current-voltage (I–V) characteristics allowed us to define the critical current Ic up to 0.8 K. At 20 mK, Ic showed a Fraunhofer-like pattern as a function of the perpendicular magnetic field (Supplementary Fig. 5a), giving evidence that the supercurrent is not due to a superconducting short-circuit (see Supplementary Note 4 for the data of other devices). The Ic(T) curve shown in Fig. 2b is convex, suggesting that this JJ is in the short-junction limit23. A theoretical fit19,23 (red solid line) to the data yields the transparency \({{{{{{{{\mathcal{T}}}}}}}}}_{{{{{{{{\rm{crit}}}}}}}}}\simeq 0.7\) with the transition temperature Tc = 1.15 K that is consistent with the Tc of Pd-BST.

When SNS-junctions have a high interface transparency, electrons can be Andreev-reflected multiple times at the SN interface without losing coherence. Such a process is called multipe Andreev reflection (MAR), which is discernible in the I–V characteristics. As shown in Fig. 2c, we observed several peaks in the plots of dI/dV vs. Vdc at various T, which is characteristic of MAR (for the data up to a higher Vdc, see Supplementary Note 5 and Supplementary Fig. 6); at 20 mK, if we assign the index n from 2 to 9 as indicated in the figure, the plot of the voltage at the peak (Vn) vs. 1/n lies on a straight line (Fig. 2c inset), which is the key signature of MAR. From the slope of this linear fit, we obtain the superconducting gap ΔSC = 184 μeV. The MAR feature is observed with the index n up to 9 and at temperatures up to 1.0 K, which points to a strong superconducting proximity effect. Knowing ΔSC, we can estimate the coherence length \(\xi =\frac{\hslash {v}_{{{{{{{{\rm{F}}}}}}}}}}{\pi {{{\Delta }}}_{{{{{{{{\rm{SC}}}}}}}}}}\) = 390 nm in the proximitized BST, where the Fermi velocity vF = 3.69 × 105 ms−1 reported for BST24 is used; this ξ confirms the short-junction nature of our JJ.

By fitting the linear portion of the I–V characteristic at high Vdc above 2ΔSC with a straight line (red dashed line in Fig. 2d), one can estimate the excess current Ie = 0.815 μA; also, from the slope of this linear fit, the normal-state resistance RN = 266 Ω is obtained. Using Ic = 0.374 μA at 20 mK, we obtain the eIcRN product of 99.5 μeV, which gives the eIcRN/ΔSC ratio of 0.54. This is among the largest ratio reported for a TI-based JJ19,20. Furthermore, based on the Octavio–Tinkham–Blonder–Klapwijk theory25,26, the other ratio eIeRN/ΔSC = 1.18 gives the interface transparency \({{{{{{{{\mathcal{T}}}}}}}}}_{{{{{{{{\rm{OTBK}}}}}}}}}\simeq\) 0.8. This \({{{{{{{{\mathcal{T}}}}}}}}}_{{{{{{{{\rm{OTBK}}}}}}}}}\) is in reasonable agreement with the transparency \({{{{{{{{\mathcal{T}}}}}}}}}_{{{{{{{{\rm{crit}}}}}}}}}\) obtained from Ic(T) mentioned above. Therefore, all the indicators [i.e., Ic(T) behavior, MAR feature, eIcRN/ΔSC ratio, and excess current] demonstrate that the TI nanowire in our device is experiencing a strong superconducting proximity effect thanks to a high interface transparency.

Shapiro response

When a phase-locked conventional JJ having a 2π-periodic current-phase relation (CPR) is irradiated with an rf wave of frequency f, Shapiro steps27 show up at quantized voltages Vm equal to \(\frac{mhf}{2e}\), where h is the Planck constant and the step index m is an integer. However, if topological Majorana bound states exist in a JJ, they contribute a 4π-periodic CPR22, which leads to the disappearance of Shapiro steps with odd-integer m. The realistic situation where 2π- and 4π-periodic CPRs coexist has been theoretically examined28, and it was concluded that at lower frequency and at lower rf power, the 4π-periodicity becomes more visible in terms of the missing Shapiro steps, even when the 4π-periodic contribution is relatively small. For a JJ based on the 2D TI system HgTe, Bocquillon et al. reported29 missing steps with m up to 9, but experiments based on 3D TIs found only the m = 1 step to be missing12,19,30,31,32. As shown in Fig. 3, the m = 1 step is clearly missing at rf frequencies up to 3.6 GHz in our device at 20 mK, while the first step becomes visible at 4.5 GHz. Wiedenmann et al. argued30 that the m = 1 step becomes missing only when f is smaller than the characteristic frequency f4π ≡ 2eRNI4π/h, where I4π is the amplitude of the 4π-periodic current. The crossover frequency of our device, around 4 GHz, suggests I4π ≃ 30 nA. This gives the ratio I4π/Ic ≃ 0.08.

a–d Mapping of dI/dV measured under the irradiation of rf waves at various frequencies (2.0, 2.95, 3.6, and 4.5 GHz) as functions of rf excitation and the dc voltage V appearing on the JJ, which is normalized by hf/(2e) to emphasize the Shapiro-step nature of the response. When there is a plateau (Shapiro step) at Vm in the V vs. Ibias curve, the slope of the curve, dV/dI, becomes zero at the plateau, which means that dI/dV diverges at Vm; therefore, the yellow vertical lines occurring at regularly-spaced V is the signature of Shapiro steps.

The missing first Shapiro step is expected to be gradually recovered with increasing temperature, because thermal excitation causes quasiparticle-poisoning of the Majorana bound states and smears the 4π-periodicity. As shown in Fig. 4a–c for 3.6 GHz, this is indeed observed in our device, giving support to the topological origin of the effect12,19,30,31,32.

It is prudent to mention that the m = 2 Shapiro step is also (partially) suppressed at low frequencies in our 20-mK data (Fig. 3a, b). This is due to the hysteretic I–V characteristic of an underdamped JJ19. To rule out this mechanism as the origin of the missing m = 1 step, we show 2.95-GHz data taken at 800 mK in Fig. 4d; here, one can see that even at a high enough temperature where the hysteretic I–V behavior is gone (see Supplementary Note 6 and Supplementary Fig. 7), the m = 1 step is still missing. We note that, in addition to taking the data of dV/dI vs. Ibias with the ac technique, we have further measured the straightforward I–V characteristics with a dc technique to completely rule out any hysteresis at 800 mK. We also note that it was argued that Landau–Zener transitions33 can mimic the behavior expected for the 4π-periodic contribution when the JJ has a very high transparency close to 134, but the transparency of our JJ is not that high. Hence, the Shapiro-step data of our device strongly suggest that a 4π-periodic contribution to the CPR exists in our proximitized TI nanowire. This gives possible evidence for topological Majorana bound states22, although one can never nail them down with the Shapiro-step data alone. The observation of missing first Shapiro step was reproduced in two more devices as shown in the Supplementary Note 7 and Supplementary Fig. 8.

Discussion

In our STEM studies, by comparing different samples with the Pd pads aligned differently with respect to the crystallographic axes of BST, we found that the diffusion speed of Pd inside BST is slower along the 〈110〉 direction than the \(\langle 1\bar{1}0\rangle\) direction (see Supplementary Note 1 and Supplementary Fig. 1). The JJs reported here were aligned such that Pd diffuses along the slower 〈110〉 direction. We presume that a major part of the Pd diffusion and the structure conversion occurs already during the thermal deposition of Pd due to the heat coming from the crucible, but the exact understanding of the process requires dedicated studies.

The results presented here demonstrate a route to realize robust proximity-induced superconductivity in a TI nanowire. The induced superconductivity presents possible evidence for a topological nature in terms of the 4π-periodicity caused by Majorana bound states which disperse along the nanowire22. Note that these dispersive Majorana bound states cannot themselves be used for topological qubits to encode quantum information, for which localized MZMs are required. In this regard, our superconducting TI nanowire platform would be suitable for realizing a recent theoretical proposal4 to employ gating to create MZMs that are protected by a large subband gap to make them more robust against potential fluctuations due to disorder. The present platform further gives us an additional tuning knob, that is, the phase difference between the two SCs sandwiching the TI nanowire; by making a SQUID loop, one can tune the phase difference with a small magnetic field. Since it was argued35,36 for a non-topological semiconductor platform that topological superconductivity can be engineered within a JJ by combining such a phase difference with an in-plane magnetic field, it would be interesting to see the role of phase difference in our TI-nanowire platform. Obviously, the construction of our system offers a lot of tuning knobs and its fabrication-friendly nature opens up an exciting prospect for exploring topological mesoscopic superconductivity.

Methods

Sample preparations

(Bi1−xSbx)2Te3 films were grown with a molecular beam epitaxy (MBE) technique on sapphire (0001) or InP (111)A substrates by co-evaporating high-purity Bi, Sb, and Te from Knudsen cells in a ultra-high vacuum chamber. The Sb/(Bi + Sb) flux ratio was 0.84, 0.90, and 0.67 for film 1 (used for device 1), film 2 (used for devices 2 and 3), and the STEM sample, respectively. After the electron-beam lithography using a Raith Pioneer II system, 20-nm-thick Pd layer was deposited onto the BST film by thermal evaporation from an alumina crucible, and a lift-off process was performed to leave the designed Pd pads/electrodes. Before the Pd deposition, the surface of the BST film was cleaned by Ar-plasma etching (10 W for 2 min).

STEM experiments

The focused ion beam (FIB) system FEI Helios Nanolab 400s was used for preparing the Pd/BST/InP multilayer lamella specimens. Before cutting with Ga ions of FIB, a layer of carbon (~160 nm) and a layer of Pt (~2 μm) were deposited on the sample surface to protect the specimen from damage. Plasma cleaning was carried out afterwards to remove the surface contamination. An FEI Titan 80–200 ChemiSTEM microscope, equipped with a Super-X EDX spectrometer and STEM annular detectors, was operated at 200 kV to collect HAADF images and EDX results. The convergence angle of the electron-beam probe was set to 24.7 mrad and the collection angle was in the range of 70–200 mrad. The Dr. Probe software package was used for HAADF image simulation37. VESTA software was used for drawing the crystal structures.

Device fabrication and measurements

Since the Pd-electrode pattern was deposited onto a continuous BST film, for JJ devices we partially dry-etched the BST films with Ar plasma (50 W for 3 min) to electrically separate the electrodes (the dark-blue area in Fig. 2a is the etched part). The JJ devices were measured in dry dilution refrigerators (Oxford Instruments Triton200/400) with the base temperature of ~20 mK. Both dc and low-frequency ac (~14 Hz) lock-in techniques were employed in a pseudo-four-terminal configuration. For the Shapiro-step measurements, rf wave was irradiated to the JJs by using a coaxial cable placed ~2 mm above the device, and dV/dI was measured with a lock-in while sweeping the bias current Ibias in the presence of the rf excitation; the voltage on the JJ was calculated by numerically integrating the data of dV/dI vs. Ibias.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Zhang, Y. & Vishwanath, A. Anomalous Aharonov-Bohm conductance oscillations from topological insulator surface states. Phys. Rev. Lett. 105, 206601 (2010).

Bardarson, J. H., Brouwer, P. W. & Moore, J. E. Aharonov-Bohm oscillations in disordered topological insulator nanowires. Phys. Rev. Lett. 105, 156803 (2010).

Cook, A. & Franz, M. Majorana fermions in a topological-insulator nanowire proximity-coupled to an s-wave superconductor. Phys. Rev. B 84, 201105 (2011).

Legg, H. F., Loss, D. & Klinovaja, J. Majorana bound states in topological insulators without a vortex. Phys. Rev. B 104, 165405 (2021).

Cho, S. et al. Aharonov-Bohm oscillations in a quasi-ballistic three-dimensional topological insulator nanowire. Nat. Commun. 6, 7634 (2015).

Jauregui, L. A., Pettes, M. T., Rokhinson, L. P., Shi, L. & Chen, Y. P. Magnetic field-induced helical mode and topological transitions in a topological insulator nanoribbon. Nat. Nanotech. 11, 345–351 (2016).

Dufouleur, J. et al. Weakly-coupled quasi-1D helical modes in disordered 3D topological insulator quantum wires. Sci. Rep. 7, 45276 (2017).

Ziegler, J. et al. Probing spin helical surface states in topological HgTe nanowires. Phys. Rev. B 97, 035157 (2018).

Münning, F. et al. Quantum confinement of the Dirac surface states in topological-insulator nanowires. Nat. Commun. 12, 1038 (2021).

Rosenbach, D. et al. Gate-induced decoupling of surface and bulk state properties in selectively-deposited Bi2Te3 nanoribbons. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/2104.03373 (2021).

Legg, H. F. et al. Giant magnetochiral anisotropy from quantum confined surface states of topological insulator nanowires. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/2109.05188 (2021).

Rosenbach, D. et al. Reappearance of first Shapiro step in narrow topological Josephson junctions. Sci. Adv. 7, eabf1854 (2021).

Bai, M. et al. Novel self-epitaxy for inducing superconductivity in the topological insulator (Bi1−xSbx)2Te3. Phys. Rev. Materials 4, 094801 (2020).

Liu, J. et al. Spin-filtered edge states with an electrically tunable gap in a two-dimensional topological crystalline insulator. Nat. Mater. 13, 178–183 (2014).

Finlayson, T., Reichardt, W. & Smith, H. Lattice dynamics of layered-structure compounds: PdTe2. Physi. Rev. B 33, 2473 (1986).

Guggenheim, J., Hulliger, F. & Muller, J. PdTe2, a superconductor with CdI2 structure. Helv. Phys. Acta 34, 408–410 (1961).

Karki, A. B., Browne, D. A., Stadler, S., Li, J. & Jin, R. PdTe: a strongly coupled superconductor. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 24, 055701 (2012).

Volkov, A. F., Magnée, P. H. C., van Wees, B. J. & Klapwijk, T. M. Proximity and Josephson effects in superconductor-two-dimensional electron gas planar junctions. Phys. C: Supercond. 242, 261–266 (1995).

Schüffelgen, P. et al. Selective area growth and stencil lithography for in situ fabricated quantum devices. Nat. Nanotechnol. 14, 825–831 (2019).

Ghatak, S. et al. Anomalous Fraunhofer patterns in gated Josephson junctions based on the bulk-insulating topological insulator BiSbTeSe2. Nano Lett. 18, 5124–5131 (2018).

Bretheau, L. et al. Tunnelling spectroscopy of Andreev states in graphene. Nat. Phys. 13, 756–760 (2017).

Fu, L. & Kane, C. L. Superconducting proximity effect and Majorana fermions at the surface of a topological insulator. Phys. Rev. Lett. 100, 096407 (2008).

Galaktionov, A. V. & Zaikin, A. D. Quantum interference and supercurrent in multiple-barrier proximity structures. Phys. Rev. B 65, 184507 (2002).

He, X., Li, H., Chen, L. & Wu, K. Substitution-induced spin-splitted surface states in topological insulator (Bi1−xSbx)2Te3. Sci. Rep. 5, 1–6 (2015).

Octavio, M., Tinkham, M., Blonder, G. E. & Klapwijk, T. M. Subharmonic energy-gap structure in superconducting constrictions. Phys. Rev. B 27, 6739–6746 (1983).

Flensberg, K., Hansen, J. B. & Octavio, M. Subharmonic energy-gap structure in superconducting weak links. Phy. Rev. B 38, 8707 (1988).

Shapiro, S. Josephson currents in superconducting tunneling: The effect of microwaves and other observations. Phys. Rev. Lett. 11, 80 (1963).

Dominguez, F. et al. Josephson junction dynamics in the presence of 2π- and 4π-periodic supercurrents. Phys. Rev. B 95, 195430 (2017).

Bocquillon, E. et al. Gapless Andreev bound states in the quantum spin Hall insulator HgTe. Nat. Nanotechnol. 12, 137–143 (2017).

Wiedenmann, J. et al. 4 π-periodic Josephson supercurrent in HgTe-based topological Josephson junctions. Nat. Commun. 7, 1–7 (2016).

Le Calvez, K. et al. Joule overheating poisons the fractional ac Josephson effect in topological Josephson junctions. Commun. Phys. 2, 4 (2019).

de Ronde, B., Li, C., Huang, Y. & Brinkman, A. Induced topological superconductivity in a BiSbTeSe2-based Josephson junction. Nanomaterials 10, 794 (2020).

Dominguez, F., Hassler, F. & Platero, G. Dynamical detection of Majorana fermions in current-biased nanowires. Phys. Rev. B 86, 140503 (2012).

Dartiailh, M. C. et al. Missing Shapiro steps in topologically trivial Josephson junction on InAs quantum well. Nat. Commun. 12, 78 (2021).

Fornieri, A. et al. Evidence of topological superconductivity in planar Josephson junctions. Nature 569, 89–92 (2019).

Ren, H. et al. Topological superconductivity in a phase-controlled Josephson junction. Nature 569, 93–98 (2019).

Barthel, J. Dr. Probe: a software for high-resolution STEM image simulation. Ultramicroscopy 193, 1–11 (2018).

Nellist, P. & Pennycook, S. The principles and interpretation of annular dark-field Z-contrast imaging. Adv. Imaging Electron Phys. 113, 147–203 (2000).

Acknowledgements

We thank F. Yang for his help at the initial stage of this work and H. Legg for helpful discussions. This project has received funding from the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation program (grant agreement No. 741121) and was also funded by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG, German Research Foundation) under CRC 1238-277146847 (Subprojects A04 and B01) as well as under Germany’s Excellence Strategy-Cluster of Excellence Matter and Light for Quantum Computing (ML4Q) EXC 2004/1-390534769. G.L. acknowledges the support by the Research Foundation-Flanders (FWO, Belgium), file nr. 27531 and 52751.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.A. conceived the project. M.B. fabricated the devices. A.B., G.L., A.U., and A.T. grew TI thin films. X.-K.W., M.L., and J.M. performed the STEM analyses. M.B. and J.F. measured the devices. Y.A., M.B., and J.F. analyzed the transport data. Y.A., M.B., and X.-K.W. wrote the manuscript with inputs from all authors.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Materials thanks Marcel Franz and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary handling editors: Toru Hirahara and Aldo Isidori.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Bai, M., Wei, XK., Feng, J. et al. Proximity-induced superconductivity in (Bi1−xSbx)2Te3 topological-insulator nanowires. Commun Mater 3, 20 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43246-022-00242-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43246-022-00242-6