Abstract

Disorder arising from random locations of charged donors and acceptors introduces localization and diffusive motion that can lead to constructive electron interference and positive magnetoconductivity. At very low temperatures, 3D theory predicts that the magnetoconductivity is independent of temperature or material properties, as verified for many combinations of thin-films and substrates. Here, we find that this prediction is apparently violated if the film thickness d is less than about 300 nm. To investigate the origin of this apparent violation, the magnetoconductivity was measured at temperatures T = 15 – 150 K in ten, Sn-doped In2O3 films with d = 13 – 292 nm, grown by pulsed laser deposition on fused silica. We observe a very strong thickness dependence which we explain by introducing a theory that postulates a second source of disorder, namely, non-uniform interface-induced defects whose number decreases exponentially with the interface distance. This theory obeys the 3D limit for the thickest samples and yields a natural figure of merit for interface disorder. It can be applied to any degenerate semiconductor film on any semi-insulating substrate.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Many descriptions and analyses of disorder in metals and highly doped semiconductors have appeared in the literature1,2,3,4, partly because degenerate semiconductor films on semi-insulating substrates are an important part of the electronics industry. Often the substrate has to be transparent to visible light, requiring materials such as sapphire or fused silica (FS). These materials are low cost and stable but can have a serious effect on the electrical properties of the film since, in general, their lattices do not match that of the film. Many of the useful transparent conductive films are oxides, and they include Ga-doped ZnO (GZO), Al-doped ZnO (AZO), and Sn-doped In2O3 (ITO)(ref. 5). In studies of GZO films grown by pulsed laser deposition (PLD), we have found that substrates such as sapphire or FS generate a nonconductive layer (“dead layer”) of thickness δd ≈ 20–25 nm in the film next to the interface6. Itagaki et al. found a similar-sized dead layer for AZO grown on sapphire by RF sputtering, but they also developed a ZnON buffer layer that led to a greatly reduced δd (ref. 7). Similarly, for ITO grown on silicon by PLD, Cleary et al.8 reported a dead layer δd ≈ 14 nm. All of those cases involved thin films mismatched to their substrates, and a common feature was a mobility μ that decreased strongly at low thicknesses, especially for d ≤ 50 nm. In contrast, the electron concentration n tended to be constant over the whole range d > δd as long as it was properly calculated by taking the dead layer into account, i.e., n = nsheet/(d − δd), not nsheet/d (ref. 6). It was found that the variation of μ with d could often be fitted to an equation μ = μ0/[1 + dμ/(d − δd)], where the values of dμ and δd gave a measure of interface quality6; in general, however, such an equation had no clear physical basis. In this work, we develop a model based on two, well-defined sources of disorder: (1) the uniform (U) disorder arising from the random arrangement of charged donors and acceptors in any highly doped material; and (2) a nonuniform (NU) disorder generated by the film/substrate interface. As shown below, this model correctly predicts magnetoconductivity over a wide range of film thicknesses, d = 13–292 nm, and temperatures, T = 15–200 K, and additionally is able to provide a simple, numerical method of characterizing interface quality.

A convenient way to investigate disorder involves magnetoconductivity, defined as Δσ(B) = σ(B) − σ(0), where B is the magnetic-field strength. Classical analysis, ignoring the wave nature of the electrons, finds that Δσ(B) is negative for non-degenerate electrons and vanishes for degenerate electrons. However, quantum analysis of degenerate electrons finds a small positive contribution to Δσ(B), termed quantum magnetoconductivity (QMC). The QMC arises from electron waves encountering a small fraction of loops in their multiple diffusive scattering paths. Since loops allow traversal in either direction, and each distance is exactly the same, constructive interference can occur at the entry point. This constructive interference increases the probability of loop-type paths, which then decreases the conductivity σ due to the retrograde motion inherent in a loop. The magnitude of this effect is typically about −0.001σ, and is sometimes called “weak localization”2. For this process to occur, electron phase must be maintained during the interference event; however, phase can be randomized by a magnetic field or inelastic phonon scattering. A theory of this phenomenon in three dimensions has been developed by Kawabata4 and yields the following equations:

where

Here D(T) is the electron diffusion coefficient, τph is the inelastic electron–phonon scattering time, and l(B) is a “magnetic length” defined by l(B) = (ħ/eB)1/2 = 25.656 nm at B = 1 tesla, the field strength used for our measurements. In Eq. 2, we have modified Kawabata’s formula by setting τph = m*μph/e, and also by invoking the Einstein relation to get D = (m*)(vf)2(μtot)/3e, where vf is the Fermi velocity9. It is very important that n and μtot in Eq. 2 can each be independently determined from the Hall effect, which involves measurements of only current, voltage, and magnetic field10. Then, since μph(T) is the only unknown quantity in Eqs. 1 and 2, its value also is independent of any material parameters.

At very low temperatures, τph, and thus also μph, will be large since few phonons are present. In such a case, δ « 1, and Kawabata’s theory4 gives Δσ(B) = 2.908B1/2 S cm−1, true for any material and independent of temperature. This is a maximum value of Δσ since μph(T) will always decrease at higher T because more phonons will be available to scatter electrons. Since B = 1 tesla in our experiments, the theory predicts that Δσ ≤ 2.9 S cm−1, at any temperature. In earlier studies we verified this prediction in several different degenerate semiconductor materials, e.g., ZnO, GaN, β-Ga2O39, ZnGa2O411, ScN, In2O3, and Si; however, we eventually realized that it seemed to hold only in samples with a thickness of about 300 nm or larger. Indeed, for much thinner films we sometimes have found Δσ » 2.9 S cm−1. This fact suggests that the film/substrate interface may be involved, and indeed, as mentioned above, much literature attests to the reduction of measured mobility (μtot) in very thin films on lattice-mismatched substrates6,7,8. In contrast, for our growth conditions of ITO on FS, given below, we find that μtot in the thinnest film (13 nm) is only about 20% lower than that in the thickest film (292 nm). On the other hand, Δσ varies about a factor 10 between these two films. Thus, QMC is a very sensitive and effective way to study and quantify interface disorder.

In this work, we develop a model for Δσ vs d that quantitatively explains the apparent violation of Kawabata’s theory in very thin films. The model is applied to ten ITO films of thickness 13–292 nm and yields three fitting parameters, including ΔσU, the uniform component of the disorder. In turn, ΔσU allows calculation of mobility μph due to inelastic phonon scattering, and μph can be related to an effective energy of the phonons involved in the scattering.

Results and discussion

Effects of nonuniform disorder on QMC

Kawabata’s theory, Eqs. 1 and 2, applies to a degenerate, disordered material in which the disorder is uniform is the sense that the density of charged centers, and thus that of the loops, is constant over the whole volume. We will designate the contribution to Δσ from these uniformly distributed loops as ΔσU. However, the interface contribution to disorder, ΔσNU, is very nonuniform in the direction perpendicular to the interface, and in general will decrease rapidly with distance z from the interface. We postulate that ΔσNU(z) = ΔσNU(0)[exp(−z/β)] and indeed, such an exponential variation is reasonable and will turn out to fit the data very well. Here, both ΔσU and ΔσNU(0) are constants that are related to the density of the loops and also to their sizes and orientations with respect to the direction of B. We now model the layer as sheets of thickness dz parallel to the interface; thus a sheet at distance z from the interface will have a conductance of Δσ(z)dz = ΔσU{1 + [ΔσNU(0)/ΔσU]exp(−z/β)}dz. It is convenient to define RNU = ΔσNU(0)/ΔσU, that is, the ratio of the interface-generated QMC at z = 0 to the uniform QMC ΔσU, which is independent of the interface. Since conductances are additive, the measured conductivity Δσ will be the integral of Δσ(z)dz divided by d, giving

Below we will determine the parameters ΔσU, RNU, and β by fitting Δσ(d) vs d at several different temperatures.

Comparison of our 3D model with an alternative 2D model

Our present model assumes 3D QMC for all the samples, even the 13-nm one. But suppose that 2D QMC is more appropriate for such thin layers, and a change from 3D to 2D accounts for part or all of the observed increase in Δσ for thinner layers. We must begin our consideration of this question by examining the various “lengths” that might be important in thin-film conductivity analysis. (1) The size of the electron is about 2π/kf(n) ≈ 2.46 nm; (2) the elastic-scattering mean free path may be written as λelas(n,μtot) = (ħ/e)(3π2n)1/3μtot, ≈ 6–7 nm, depending on μtot; (3) the “magnetic length” = (ħ/eB)1/2 = 25.7 nm at B = 1 tesla. For our samples, these three lengths are not significantly dependent on temperature, and therefore the 13- and 26-nm samples may possibly be expected to have some 2D character. We first note that kfλelas ≥ 16 for our samples, and indeed it is required that kfλelas » 1 for the validity of a perturbation theory such as Kawabata’s. (This relationship should not be confused with the Ioffe-Regel criterion, kfλelas = 1, which applies to the metal-insulator transition point in heavily-doped semiconductors such as ITO2. In that case, kfλelas » 1 denotes metallic behavior, primarily defined by finite (non-zero) conductivity as T → 0, which indeed holds for our ITO samples, as seen below.) Another length, the inelastic-scattering mean free path, given by λinelas(n,μtot) = (ħ/e)(3π2n)1/3(μtotμph)1/2, is less than 292 nm for T > 20 K, and less than 13 nm at about 200 K. Thus, from these length considerations, we would guess that the 292-nm sample might be 3D-like above 20 K, and most of the other samples, 3D-like above 200 K. However, we can be much more definitive about the 3D nature of the 292-nm sample, as shown below.

To proceed further, we must deal with an established 2D theory, and an obvious choice is that presented by Hikami, Larkin, and Nagaoka (HLN)12. This theory is cast in terms of a parameter “aτε” where a = 4DeB/ħ and τε represents the dominant form of inelastic scattering, whether electron–electron, electron–phonon, or spin–orbit scattering. For doped semiconductors, with typical concentrations n ~ 5 × 1020 cm−3, a factor 100× less than that of metals (n ~ 5 × 1022 cm−3), phonon scattering will be dominant. Indeed, we find that our electron–phonon scattering formula, Eq. 4, well describes the temperature dependence of our QMC data, as shown earlier9. We then set τε = τph, and will for convenience define the

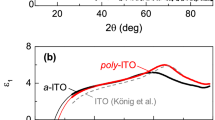

associated mobility as μph = eτph/m*. This term then fits into δ(B,T), Eq. 2 of the present paper, and gives by far the dominant temperature dependence in δ(B,T) since n and μtot(T) are nearly flat. For comparison with HLN’s 2D theory, we consider the very low temperature data, for which δ « 1. For our 292-nm sample, Δσ(B,T), with B = 1 tesla in our experiments, is plotted in Fig. 1.

Note that the low-T data, for which δ « 1, are very close to Kawabata’s prediction, i.e., Δσ(low-T) = 290.8 S m−1. This number involves no material parameters and is not adjustable in any way. Because Δσ vs T agrees so closely with 3D theory, we are justified in using Eqs. 1 and 2 to calculate μph(T), representing the inelastic phonon scattering mechanism, as described above. This same scattering mechanism must of course be incorporated in any 2D theory applied to the same sample, including the HLN theory. Fortunately, their parameter “aτε” can be written in terms of our parameter δ (Eq. 2) as (aτε)−1 = (2/3)δ. (The “2/3” arises from the change from 3 to 2 dimensions and is unimportant in the subsequent calculations.) HLN give a formula (their Eqn. 19) for aτε » 1 (or δ « 1): Δσ2D = (e2/2π2ħ)ln(1/δ), where e2/2π2ħ = 1.233 × 10−5 S, the unit of quantum conductance. To convert the units in Δσ2D from S to S m−1, we divide by 292 × 10−9 m, and the result is plotted in Fig. 1. The fit is not very good and there are no undetermined parameters that could make it better. However, we can go one step further by comparing 2D and 3D for the 13-nm sample, which should give a much better fit to the HLN formula than was found for the 292-nm sample. As shown in the inset of Fig. 1, the 2D fit at 13-nm thickness is not better than that at 292-nm, but actually much worse; therefore, the large increase of Δσ in thinner samples cannot be attributed to a switch from 3D character in the thicker samples to 2D in the thinnest ones.

Temperature and thickness dependence of mobility and sheet concentration

Figure 2 presents the sheet concentration nsq and mobility μtot vs thickness d at room temperature for all ten ITO samples. The utility of an nsq vs d plot is to show the variation of the volume concentration n vs d, since n is just the slope of nsq vs d; also, the intercept on the abscissa gives the dead layer thickness, δd. The slope gives n = 5.65 × 1020 cm−3, nearly constant with thickness down to that of the thinnest layer, only 13 nm. Furthermore, δd < 1 nm, far lower than, e.g., values found for Ga-doped ZnO on sapphire or on FS6. Finally, μtot is high and also nearly constant at about 38 cm2 V−1 s−1, again unusual for lattice-mismatched growth. Thus, the present set of samples is ideal for this study.

Figure 3 displays temperature dependences of the resistivity ρ0(B = 0), mobility μtot, and concentration n, for the thickest (292 nm) and thinnest (13 nm) layers. First note that n is constant in both layers, showing good degeneracy, and the values of n differ by only 3% in magnitude. Secondly, ρ0 and μtot each have about a 20% difference between their respective values in thick and thin layers, although it would normally be much larger in typical lattice-mismatched systems. But the most astonishing difference involves the values of Δσ, differing by a factor 10 at low temperatures. This huge effect on Δσ in very thin films is the subject of this study and will be shown to arise from interface disorder.

Carrier concentration n: open red squares, 13 nm sample; open blue circles, 292 nm sample. Mobility μ: closed red squares, 13 nm; closed blue circles, 292 nm. Resistivity, ρ0: dashed red line, 13 nm; dashed blue line, 292 nm. Magnetoconductivity Δσ: red solid line, 13 nm; blue solid line, 292 nm. At low temperatures, Δσ has by far a stronger thickness dependence than that of n, μ, and ρ0.

However, it also reveals that QMC is a very sensitive probe of interface effects, much more so than that of other electrical properties, such as n and μ.

Figure 4 shows plots of Δσ vs d at temperatures of 15, 30, 50, 80, and 150 K. (Other measurements of Δσ vs d, not shown to avoid clutter, are at 20, 40, 60, 70, 100, and 130 K). Each curve is fitted to Eq. 3, σ(d) = ΔσU{1 + [RNUβ/d][1 – exp(−d/β)]}, where ΔσU represents the uniform disorder arising mainly from the randomness of the donors, and RNU = ΔσNU(0)/ΔσU, i.e., the ratio of the nonuniform disorder at z = 0 to the uniform disorder, which is constant everywhere. At B = 1 tesla, fits of Δσ(d) vs d at each temperature yield ΔσU, RNU, and β. It turns out that β = 6.15 ± 0.6 nm for all samples, nearly independent of temperature and thickness, while both ΔσU and RNU decrease as temperature increases. The temperature independence of β occurs because the spatial distribution of loops is fixed. However, the ability of the loops to affect conductivity, represented by ΔσU and ΔσURNU, is temperature dependent because the strong inelastic phonon interactions at higher temperatures destroy the constructive electron-wave interference more completely. Besides temperature dependences we must also consider the thickness dependences of ΔσU and ΔσNU. At a given temperature, ΔσU remains constant as d is increased, but ΔσNU continuously decreases because of the [1 – exp(−d/β)] term, until at some thickness, designated as d*, ΔσNU < ΔσU. The value of d* is given by solving [RNUβ/d*][1 – exp(−d*/β)] = 1, but for practical purposes, d* ≈ RNUβ. Its significance is that, for d > d*, the surface is far enough away that it is basically unaffected by the interface damage propagating upward. Thus, d* serves as a useful figure of merit for a layer/substrate interface. It is expected that homoepitaxial layers should have a good interface and thus a small d*, and we have found this to generally be true. Also, a good buffer layer7 should make d* smaller. For T = 15, 80, and 150 K, d* = 300, 122, and 76 nm, respectively. A reasonable fit to all of the d* values up to 150 K gives d*(T) ≈ [330e−T/42 + 63] nm. For temperatures much higher than 150 K, e.g., 300 K, the first term is negligible so that d* ≈ 63 nm. This rough value of d* might suffice as a first estimate of the required thickness of ITO on FS to minimize surface disorder for a device operating at room temperature.

Solid symbols, experimental values of magnetoconductivity Δσ; solid lines, theoretical fits of symbols to Δσ (d) = ΔσU{1 + [RNUβ/d][1 – exp(−d/β)]}. Red circles, 15 K; green triangles, 30 K; black triangles, 50 K; dark blue squares, 80 K; light blue circles, 150 K. Dashed line, Δσ = 2.908 S cm−1, which is the theoretical maximum QMC for uniform disorder.

Determination of mobility related to inelastic phonon scattering

To investigate interfaces by QMC, only conductivity measurements are necessary, not Hall-effect measurements. However, to study the phonons responsible for inelastic scattering, represented by μph, we must also know n and μtot (obtained from the Hall effect) so that the only unknown in Eq. 2 is μph. It is worth noting that the interface disorder is not expected to greatly affect the phonon spectrum itself, but its nonuniformity can affect our ability to study it via Kawabata’s theory, which requires uniformity. In short, only the uniform portion, ΔσU, is subject to his theory. (In earlier studies9,11,13 of μph in various materials, we fortunately used very thick samples because, as seen in Eq. 3, the uniform component of disorder ΔσU then becomes the dominant term.) From ΔσU in the present samples we determine μph for T = 15–150 K and the results are shown in Fig. 5. For comparison, we also plot μtot for the 292-nm sample. Clearly, μph is strongly temperature dependent, as would be expected, but it does not greatly influence the temperature dependence of μtot, because μph−1 « μtot−1over the whole range. The magnitudes of ΔσU(T) at all temperatures are consistent with Kawabata’s limit, i.e., Δσ(d) ≤ 2.9 S cm−1, and they also lead to reasonable values of μph.

On the other hand, to fully understand μph we must include all of the phonons responsible for the electron–phonon scattering. That is a very difficult problem because of the large number (80) of phonon branches in In2O3. However, a different approach, introduced earlier9, is to calculate a single effective phonon energy, Eph(T) = kTph(T), that produces the required scattering at temperature T. The calculation involves three steps: Step 1, fit Δσ(d,T) vs d, Eq. 3, to get ΔσU(T); Step 2: solve ΔσU(μph,T) for μph(T) in Eqs. 1 and 2; Step 3: solve μph(Tph,T) for Tph in Eq. 4. The results are shown in Fig. 6, and the calculated values of Eph cover an energy range of 7–76 meV over the temperature range 15–150 K. There is no certainty that the Eph vs T curve can be extended beyond 150 K, but if so, we can fit it with Eph = 137[1 – exp(−T/172)] –4.17, which leads to Eph = 109 meV at 300 K.

The reasonableness of these phonon energies can be addressed by investigating their origin, the phonon density of states (DoS), via DFT. For comparison, in a simple semiconductor such as GaN, with two atoms in the unit cell, only one phonon is dominant for scattering electrons at room temperature, a longitudinal optical phonon of energy 93 meV. For more complicated semiconductors, such as Ga2O3 with ten atoms in the unit cell, or In2O3 with eighty, many phonons take part in the scattering process. Approximate14 as well as first-principles15,16 calculations of electron–phonon scattering in Ga2O3 have been carried out but only for the perfect crystal, in which symmetry considerations are very important. In a disordered crystal, such as that considered here, symmetries are broken, and the DoS of all phonons, shown in Fig. 7, becomes relevant. Note that the range of the effective phonon energies determined by QMC is very similar to the range of phonon energies calculated by DFT. However, we would expect a broadening and smoothing of the perfect-crystal DoS due to disorder, discussed below.

Solid red line: phonon density of states (DoS) for perfect-crystal In2O3 calculated by density functional theory (DFT). Vertical dashed lines: effective phonon energy Eph calculated from quantum magnetoconductivity (QMC) at temperatures 15 and 150 K, and estimated at 300 K. Note that the ranges of energies determined by DFT and QMC are quite similar.

The lowest energy structures of In2O3 are cubic bixbyite, with two atomic arrangements:17 In2O3-I, which has space group No. 199, eight formula units per unit cell, three types of In and two types of O; and In2O3-II, which has space group No. 206, eight formula units per unit cell, two types of In and one type of O atoms. In agreement with ref. 17. our DFT calculations find that these two structures have similar total energies, within 10 meV of each other. In addition, the total energies of In substituted by Sn (SnIn+1) are similar in the two phases for models with one Sn atom per crystallographic cell (80 atoms, i.e., Sn density of 9.76 × 1020 cm−3) as well as one Sn atom per primitive cell (40 atoms, i.e., Sn density of 1.95 × 1021 cm−3). We find that the phonon density of states for these model defects has minimal broadening by comparison to that of the pristine material. This can be understood from the small difference between the atomic masses of In and Sn (111.8 a.u. vs 118.7 a.u.) and the small difference between their atomic numbers (49 vs 50), suggesting that Sn has a relatively small effect on the elastic constants. This situation is different from that of degenerately Si-doped β-Ga2O3 and ZnGa2O4, where Si differs significantly from Ga both in mass (28.08 a.u. vs 111.8 a.u) and in atomic number (14 vs 49). Therefore we considered additional sources of phonon broadening. A prevalent point defect driven by degenerate doping of In2O3 is known to be the oxygen interstitial Oi17, which acts as a compensating center. We find that the phonon density of Oi−2 has a significant broadening especially in the lower part of the spectrum. In addition, we find that the main peaks in the phonon spectra of pristine In2O3-I are shifted by a few meV relative to those of In2O3-II and have different widths. Given that these two phases are equally likely to form, we expect the resulting spectral function for electron–phonon scattering to be an average of these two densities of states, resulting in additional broadening.

A final requirement of the usefulness of QMC and Eq. 3 is that it be applicable to other degenerate films on other semi-insulating substrates. Although we have only recently begun looking at other layer/substrate systems, previous unrelated programs over a two-year period had involved Ga-doped ZnO (GZO) layers of various thicknesses grown on fused silica in the same PLD system as that used for the present ITO growths. The 15-K QMC results of the GZO samples are plotted in Fig. 8 along with those of the 15-K ITO samples shown above in Fig. 4. The fitting parameters of the GZO are ΔσU = 1.26 S/cm, RNU = 6.40, and β = 30.5 nm, to be compared with those of the ITO, ΔσU = 1.33 S/cm, RNU = 44.9, and β = 6.68 nm. Interestingly, the differences in RNU and β between ITO and GZO are very large, but the difference in d* = RNUβ, 195 nm for GZO and 300 nm for ITO, is only a factor 1.5. These results demonstrate that interface damage can propagate far into the film by having either a large initial value (high RNU, as in ITO), or a large decay value (high β, as in GZO). Both are important when considering the best substrate material, or designing an appropriate buffer layer.

Comparison of interface quality for different materials, Sn-doped In2O3 (ITO) and Ga-doped ZnO (GZO), grown by the same method (pulsed laser deposition) on the same substrate material (fused silica) using the same apparatus. Squares, ITO. Circles, GZO. Solid lines, fits to Δσ (d) = ΔσU{1 + [RNUβ/d][1 – exp(−d/β)]}. The figure of merit, d* = RNUβ, is 300 nm for ITO and 195 nm for GZO.

Conclusions

We have developed a model to explain an apparent strong violation of Kawabata’s 3D theory of quantum-based magnetoconductance in degenerate semiconductors, which states that Δσ(B) ≤ 2.908B1/2 S cm−1, independent of material or temperature. We find that this theory holds well for films of thickness d = 300 nm or greater, but not for much thinner films. The Kawabata theory implicitly assumes uniform disorder, ΔσU, which would be expected from the random locations of large densities of charged donors and acceptors. However, thin films require a substrate for stability and the film/substrate interface can introduce a nonuniform disorder, ΔσNU(d), into the film. Our model includes both uniform and nonuniform types of disorder and was tested with films of ITO, d = 13–192 nm, grown on fused silica by PLD. Electron–phonon scattering theory predicts effective phonon energies Eph of 7 meV at 15 K, and 76 meV at 150 K. An extension of the scattering theory beyond 150 K, not necessarily justified, predicts Eph = 109 meV at 300 K. Density functional theory predicts a DoS with an energy range ≈ 3–107 meV, showing reasonable correlation with the QMC-derived Eph. Support for the general applicability of our Δσ vs d model, Eq. 3, comes from excellent fits to another material, GZO on fused silica. Finally, we considered an alternative model for the observation that very thin films can have a value of Δσ above the maximum permitted by Kawabata’s 3D theory. This alternative model suggested that the thinnest samples should be treated as 2D, not 3D. However, a direct comparison of 3D and 2D theories showed that the latter gave poor fits to all samples and thus could not explain the observed phenomena.

Methods

Sample growth

Ten ITO films, of thicknesses 13, 26, 37, 62, 74, 109, 149, 217, 242, and 292 nm (measured by spectroscopic ellipsometry), were deposited in a Neocera (Neocera LLC, 10000 Virginia Manor Rd # 300, Beltsville, MD 20705 USA) Pioneer 180 pulsed laser deposition system with a KrF excimer laser (Coherent COMPex Pro 110, λ = 248 nm, 10 ns pulse duration). The chamber base pressure was 2.66 × 10−6 Pa and a deposition pressure of 1.3 Pa was utilized with a 5% O2 /95% Ar gas mixture. Double-side-polished, 2-inch-diameter, fused-silica substrates were heated by a backside heater to 300 °C and rotated during deposition. The laser operated at a pulse frequency of 30 Hz and an energy density of 2.6 J cm−2 measured at the target, which was 50-mm in diameter, 6-mm thick, 99.99%-pure, and composed of 90-wt%-In2O3 and 10-wt%-SnO2. The target-to-substrate distance was 50 mm with a 45° laser angle of incidence to the target. Although these samples were not measured by X-ray diffraction (XRD), previous ITO growths by PLD on Si, in the same apparatus and under nearly identical conditions, were studied by XRD and found to be polycrystalline, even down to 10-nm thickness8. Similarly, Kim et al.18 grew ITO on plastic (PMMA) by RF sputtering at 70 °C and found amorphous growth for d < 80 nm but polycrystalline growth for thicker samples, with dominant orientations of (222), (400), (440), and (622).

Hall effect, QMC

Hall effect and conductivity measurements were carried out in a LakeShore (LakeShore Cryotronics, Inc., 575 McCorkle Blvd, Westerville, OH 43082 USA) 7500 system over a temperature range T = 10–320 K, and at magnetic-field strengths B = 0 and 1 tesla. At each value of T, the automated system produced values of mobility μ(T), carrier concentration n(T), and resistivities ρ0(T) (at B = 0), and ρB(T) (at B = 1 tesla). The experimental values of Δσ(B,T) were calculated from Δσ(B,T) = ρB(T)−1 − ρ0(T)−1, and the experimental values of μtot(T) and n(T) were given directly by the apparatus. Thus, by fitting the experimental Δσ(B,T) to the theoretical expression in Eqs. 1 and 2, the term μph(T) in Eq. 2 is the only unknown and was determined by solving Eq. 1 as a transcendental equation.

Effective phonon energy calculation

The conversion of μph(T) to an effective energy kTph(T), representing all of the phonons responsible for the inelastic scattering at that temperature, was accomplished by solving Eq. 4 as a transcendental equation. This equation has been published elsewhere9 and is a somewhat modified version of a first-order variational calculation due to Howarth and Sondheimer19. For In2O3, we use the values ε0 = 9.0, ε∞ = 4.0, and m* = 0.30m020. Because Eq. 4 is only an approximation, we present kTph(T) also as an approximation, and a more accurate analysis will require additional scattering theory. Nevertheless, the continuous dependence of the effective phonon energy has been interpreted as a mixing between the polar optical modes and nonscattering modes due to the large number of disordered donor sites21. The latter produce a particularly strong phonon mixing effect in complex oxides like β-Ga2O3 and ZnGa2O4, which have many, closely-spaced phonon branches13. A similar effect is found here for ITO by first-principles calculations, which show an interplay of mixing from Sn sites, In vacancies, and ITO polymorphism21.

Density functional theory

The total phonon density of states was calculated for the perfect crystal, ignoring disorder from all causes. For that we used the Quantum Espresso software package22, which included DFT for lattice structure, and density functional perturbation theory23 for lattice dynamical properties (DFPT). We used ultrasoft pseudopotentials with the PBEsol exchange-correlation potential24, a plane-wave cut-off of 125 Ry, and a 16 × 16 × 8 Monkhorst-Pack k-point grid for structure relaxation with a convergence criterion of 1 mRy/a.u. The Brillouin Zone sampling for lattice dynamical properties consisted of an 8 × 8 × 8 k-point grid for the electrons and a 4 × 4 × 4 q-point grid for phonons.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Mott, N. F. & Davis, E. A. Electronic Processes in Non-Crystalline Materials (Oxford University Press, 1971).

Lee, P. A. & Ramakrishnan, T. V. Disordered electronic systems. Rev. Modern Phys. 57, 287–337 (1985).

Dugdale, J. S. The Electrical Properties of Disordered Metals (Cambridge University Press, 2005).

Kawabata, A. Theory of negative magnetoresistance in three-dimensional systems. Solid State Commun. 34, 431–432 (1980).

Minami, T. Transparent conducting oxide semiconductors for transparent electrodes. Semicond. Sci. Technol. 20, S35–S44 (2005).

Look, D. C. et al. Model for thickness dependence of mobility and concentration in highly conductive zinc oxide. Opt. Eng. 52, 033801 (2013).

Itagaki, N. et al. Highly conducting and very thin ZnO:Al films with ZnO buffer layer fabricated by solid phase crystallization from amorphous phase. Appl. Phys. Exp 4, 011101 (2011).

Cleary, J. W., Smith, E. M., Leedy, K. D., Grzybowski, G. & Guo, J. Optical and electrical properties of ultra-thin indium tin oxide nanofilms on silicon for infrared photonics. Opt. Mater. Express 8, 1231–1245 (2018).

Look, D. C. & Leedy, K. D. Classical and quantum conductivity in β-Ga2O3. Sci. Rep. 9, 1290 (2019).

Look, D. C. Electrical Characterization of GaAs Materials and Devices (Wiley, 1989).

Look, D. C., Leedy, K. D., Horng, Ray-Hua, Santia, M. D. & Badescu, S. C. Electrical and optical properties of degenerate and semi-insulating ZnGa2O4: electron/phonon scattering elucidated by quantum magnetoconductivity. Appl. Phys. Lett. 116, 252104 (2020).

Hikami, S., Larkin, A. I. & Nagaoka, Y. Spin-orbit interaction and magnetoresistance in the two dimensional system. Prog. Theor. Phys. 63, 707 (1980).

Santia, M. D., Look, D. C. & Badescu, S. C. Electron-phonon coupling and electron mobility in degenerately doped oxides from first principles. Opt. Eng. 59, 067103 (2020).

Ma, N. et al. Intrinsic electron mobility limits in β-Ga2O3. Appl. Phys. Lett. 109, 212101 (2016).

Ghosh, K. & Singisetti, U. Ab initio calculation of electron-phonon coupling in monoclinic β-Ga2O3 crystal. Appl. Phys. Lett. 109, 072102 (2016).

Kang, Y., Krishnaswamy, Y. K., Peelaers, H. & Van de Walle, C. G. Fundamental limits on the electron mobility of β-Ga2O3. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 29, 234001 (2017).

Chatratin, I. et al. Role of point defects in the electrical and optical properties of In2O3. Phys. Rev. Mat. 3, 074604 (2019).

Kim, D. H., Park, M. R., Lee, H. J. & Lee, G. H. Thickness dependence of electrical properties of ITO film deposited on a plastic substrate by RF magnetron sputtering. Appl. Surf. Sci. 253, 409–411 (2006).

Howarth, D. J. & Sondheimer, E. H. The theory of electronic conduction in polar semiconductors. Proc. R. Soc. A 219, 53–74 (1953).

Preissler, N., Bierwagen, O., Ramu, A. & Speck, J. S. Electrical transport, electrothermal transport, and effective electron mass in single-crystalline In2O3 films. Phys. Rev. B 88, 085305 (2013).

Karazhanov, S. Z. et al. Phase stability, electronic structure, and optical properties of indium oxide polytypes. Phys. Rev. B 76, 075129 (2007).

Gianozzi, P. et al. Quantum ESPRESSO: a modular and open-source software project for quantum simulations of materials. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 21, 395502 (2009).

Baroni, S., de Gironcoli, S., Dal Corso, A. & Giannozzi, P. Phonons and related crystal properties from density-functional perturbation theory. Rev. Mod. Phys. 73, 515 (2001).

Perdew, J. P. et al. Restoring the density-gradient expansion for exchange in solids and surfaces. Phys. Rev. Lett. 100, 136406 (2008).

Acknowledgements

This material is based upon work supported in part by the Air Force Office of Scientific Research under award number FA9550-RY18COR800. Further financial support was provided by the Air Force Research Laboratory under Contract FA8075-14-D-0025 and the National Science Foundation under grant DMR-1800139 (T. Paskova). We wish to thank T.A Cooper, W. Rice, and D. McFarland, for critical technical support in these experiments.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

D.C.L. conceived of the project and carried out the Hall effect and magnetoconductivity modeling and calculations. K.D.L. developed the degenerate crystal growth methodology and performed the spectroscopic ellipsometry. M.D.S. and S.C.B. carried out the density functional calculations of phonon states including some aspects of disorder. All authors participated in writing the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Peer review information Primary handling editor: Aldo Isidori

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Look, D.C., Leedy, K.D., Santia, M.D. et al. Quantum magnetoconductivity characterization of interface disorder in indium-tin-oxide films on fused silica. Commun Mater 2, 33 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43246-021-00137-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43246-021-00137-y