Abstract

2D Transition Metal Dichalcogenides hold a promising potential in future optoelectronic applications due to their high photoresponsivity and tunable band structure for broadband photodetection. In imaging applications, the detection of weak light signals is crucial for creating a better contrast between bright and dark pixels in order to achieve high resolution images. The photogating effect has been previously shown to offer high light sensitivities; however, the key features required to create this as a dominating photoresponse has yet to be discussed. Here, we report high responsivity and high photogain MoS2 phototransistors based on the dual function of HfO2 as a dielectric and charge trapping layer to enhance the photogating effect. As a result, these devices offered a very large responsivity of 1.1 × 106 A W−1, a photogain >109, and a detectivity of 5.6 × 1013 Jones under low light illumination. This work offers a CMOS compatible process and technique to develop highly photosensitive phototransistors for future low-powered imaging applications.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Transition metal dichalcogenides (TMDCs) have been recently studied with great interest due to their unique electronic and optoelectronic properties. Unlike graphene, these materials have an intrinsic bandgap that makes them a promising candidate for developing future electronic devices, including transistors1, integrated circuits2, and non-volatile memory devices3. Although MoS2 has been extensively studied, other TMDC materials such as molybdenum diselenide (MoSe2), tungsten diselenide (WSe2), tungsten disulfide (WS2), and pallidum diselenide (PdSe2) have been investigated to explore interesting properties, such as interface charge transport mechanisms4, controlling doping carrier type by field emission5, developing high mobility transistors using two-dimensional (2D) hexagonal boron nitride (h-BN) dielectrics6, and understanding the influence of external stimuli on charge transport properties7.

For 2D photodetection applications, graphene as a photoactive material has been pursued for its broadband detection ability8 and fast time response speeds9,10; however, its short carrier lifetimes in the picoseconds range and small optical absorption (~2%) limits its light detection sensitivity. On the other hand, TMDCs such as MoS2 hold a promising role in future photodetectors, since they offer attractive features such as high photoresponsivities, low dark currents, and tunable bandgaps via layer thickness for wider optical absorption11,12. There have been many techniques proposed to explore its photodetection ability and to enhance its photoresponse like combining MoS2 to form hybrid materials13, heterostructures14, PN junctions15, intrinsic photogating16, and three-dimensional device structures17. Enhancing the photosensitivity with intrinsic MoS2 is highly attractive, because it can offer a simple fabrication process and complementary metal–oxide–semiconductor (CMOS) compatibility. However, to achieve simultaneously a high light sensitivity under low power operation is challenging, yet highly desirable for its use in future image sensors.

The ability to design a dominating photocurrent generation mechanism can enable the opportunity to develop application-specific performance for photodetectors. MoS2 has been known to display in visible light a combination of two photocurrent generation mechanisms: the photoconductive and photogating effect. Overall, the photogating effect can provide higher light sensitivity, since the built-in electric field from trapped photocarriers can induce more majority free carriers. Although there has been an exploration of different kinds of applications of photogating such as the use of environmental gases to provide molecular gating18 and dual photogating with optical absorbing insulators19, there is still a lack of understanding how to control this effect with TMDC materials. In addition, previous reported works using TMDCs as photoactive channels have claimed to observe a dominant photogating effect in the on-state (accumulation); however, in the off-state (depletion) the photoconductive effect dominates16,20,21. One important parameter to consider is the influence of the dielectric layer properties on the photoresponse. To enable a dominating photogating effect for all operation modes (on- and off-state), a dielectric layer with an intrinsic affinity for charge trapping would be required to generate very large photocurrents.

Here we report a low-powered highly photosensitive MoS2 phototransistor through employing high-k HfO2 dielectrics. In this device structure, HfO2 serves as both a dielectric and charge-trapping layer. The intrinsic charge-trapping property of HfO2 via oxygen vacancies helps to enhance the photoresponse by trapping the photogenerated hole carriers. As a result, the photogating effect is strongly enhanced resulting in providing simultaneously a very large responsivity of 1.1 × 106 A W−1, detectivity of 5.6 × 1013 Jones, and photogain of 1.6 × 109 under weak light detection and low power operation.

Results and discussion

Multi-layered MoS2 and device characterization

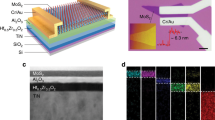

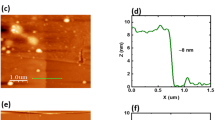

The device schematic of the HfO2-based multi-layered MoS2 phototransistor can be seen in Fig. 1a and a close-up optical microscope image of the channel region in Fig. 1b. A back-gated device configuration was selected, since it allows for direct light illumination onto the MoS2 channel region for better optical absorption. Heavily doped n++ silicon was used as a back-gate where 10 nm of atomic layer deposition (ALD) HfO2 was deposited as the dielectric layer. Next, the multi-layered MoS2 flake was mechanically exfoliated from a bulk crystal and transferred onto HfO2. Finally, top contacts of Ti (5 nm)/Au (50 nm) with channel length of 5 μm were deposited by e-beam evaporation. Details of the device fabrication process can be found in the “Methods” section. To characterize the exfoliated multi-layered MoS2, a Raman spectroscopic and atomic force microscopic (AFM) measurements were performed. The Raman spectrum in Fig. 1c shows the in-plane \(E_{2g}^1\) and out-of-plane A1g vibrational modes from the Mo-S bond in MoS2 where the two peaks were located at 382.9 and 407.7 cm−1, respectively. The wavenumber difference between the peaks was 24.8 cm−1, which is close to bulk MoS2 that has 25 cm−1. AFM height profile measurements were performed to obtain the film thickness of the multi-layered MoS2 flake as seen in Fig. 1d. Typical MoS2 flake thicknesses used in this study were in the range of 3–20 nm due to the result of our exfoliation/transferring method and in addition to evaluate near-infrared (NIR) wavelengths. Additionally, an AFM surface topographic scan of the channel region can be found in Supplementary Fig. 1.

a Device schematic of back-gated MoS2 phototransistor. b Close-up optical microscopic image of MoS2 channel region. Scale bar 10 μm. c Raman spectrum of multi-layered MoS2. The wavenumber difference between the in-plane \(E_{2g}^1\) and out-of-plane A1g modes was 24.8 cm−1. d AFM height profile of MoS2 indicating film thickness of 10 nm. e Dark condition transfer characteristics of the MoS2 phototransistor at different drain voltages: 150, 250, and 500 mV. f Dark condition output characteristics of the MoS2 phototransistor.

Next, a performance evaluation of the HfO2-based MoS2 phototransistor was analyzed under the dark condition (no light illumination). The dark transfer characteristics of the phototransistor under different drain–source voltages (VDS) of 150, 250, and 500 mV can be seen in Fig. 1e. Under VDS bias of 150 mV, the Ion/Ioff ratio was 2.92 × 107, the subthreshold swing (SS) was determined to be 142 mV/dec, the threshold voltage (VTH) was −0.71 V from the linear extrapolation method, and the field-effect mobility of 5.07 cm2 V−1 s−1 was extracted from the linear region of the ID–VG plot using the equation \(\mu = \left[ {\frac{{{\rm{d}}I_{\rm{D}}}}{{{\rm{d}}V_{\rm{G}}}}} \right]\frac{L}{{W\times {V_{{\rm{DS}}} \times }C_{{\rm{ox}}}}}\), where W is the width, L is the channel length, VDS is the drain–source voltage, and Cox is the oxide capacitance per unit area. One aspect to point out is the large SS and low field-effect mobility that was obtained. In this structure, as-deposited ALD HfO2 is used with no surface pretreatments or post-deposition annealing to preserve an amorphous defect-rich interface. Back-gated MoS2 field-effect transistors have been reported to show lower mobilities compared to top-gate structures22,23. Some of the reasons include the exposure of the channel region to environmental gaseous absorbates like O2 and H2O that deplete electrons from MoS2 via electron transferring24 and the reduction in gate capacitance density due to the contribution of non-gapless contact of transferred MoS2, which is known as the van der Waals gap25. However, an improved electrical performance for back-gated devices can be achieved by channel encapsulation26. Lastly, the dark output characteristics are seen in Fig. 1f. A close-up of the ID–VD plot at lower drain voltages can be seen in Supplementary Fig. 2. The linear relationship between the drain current and drain voltage under lower voltages indicates that our metal contacts have ohmic-type behavior.

Photoresponse performance

The general light detection process starts with the absorption of incident light by the photoactive channel when the energy condition of Ephoton ≥ Eg,MoS2 is satisfied. Next, the photogenerated electron/hole pairs are separated by the applied electric field from VDS in the depletion region where the electrons and holes are collected at the electrodes. Generally, MoS2 has two dominant photocurrent generation mechanisms in visible light, which are the photoconductive and photogating effect27,28. Typically, when observing the photoresponse of MoS2 phototransistors, its transfer characteristics will display a combination of these effects. The photoconductive effect is the increase in conductivity of the semiconductor from illumination resulting in the generation of electron/hole pairs. These photogenerated carriers get collected by the electrodes and produce an increase in the current that adds to the dark current. The photogating effect is when one of the photogenerated carriers gets trapped and acts as a built-in local electric field. For n-type semiconductors, these trapped holes induce more majority carrier electrons and causes a horizontal shift in the ID–VG curves.

An evaluation of the photoresponse with the HfO2-based MoS2 phototransistor under the illumination of blue light (λ = 460 nm) was studied. In addition, we compared its performance with the conventional SiO2-based MoS2 phototransistor with the same dielectric thickness. The effects of light illumination at different optical power densities can be seen in Fig. 2a, b for the HfO2 and SiO2 devices, respectively. As expected for both cases, there is an increase in ID as the optical power was increased. For the HfO2 device, the ID–VG illumination curves are strongly shifted toward the left indicating a strong photogating effect. Since this device without illumination displays hysteresis, we found that its hysteresis window became larger with increasing optical powers (Supplementary Fig. 9). Its optical detection under red (λ = 630 nm) and NIR (λ = 850 nm) wavelengths were also measured and displayed the same photogating behavior (Supplementary Figs. 3 and 8). In addition, a measurement under vacuum conditions (2 × 10−3 Pa) was also performed with the HfO2 device and can be seen in Supplementary Figs. 10 and 11. We found that the multi-layered MoS2 channel region could not become fully depleted due to the poor gate control (back-gate structure) and absence of gaseous absorbates (O2 and H2O) that help to deplete the channel.

Effects of light illumination with blue LED at different optical power densities at VDS = 150 mV for a HfO2 phototransistor and b SiO2 phototransistor. Close-up of the illumination curves in the accumulation mode region of c the HfO2 phototransistor and d the SiO2 phototransistor. e Photocurrent generation comparison of HfO2 and SiO2 phototransistors under illumination at 1.5 mW cm−2. f Photocurrent (IPH) versus optical power density under varying gate voltages and constant VDS = 150 mV.

Also, its output characteristics under constant illumination in comparison to the dark condition can be found in Supplementary Fig. 4. On the other hand, the SiO2 device showed a stronger photoconductive effect where its ID–VG illumination curves increased in the vertical direction. There has been a large variation in the reported responsivities29,30 and even in the dominant photoresponse behavior in SiO2-based MoS2 phototransistors. Some have reported to observing a dominating photogating effect31 or photoconductive effect32. This discrepancy comes from the interface between MoS2/SiO2 where SiO2 is well known for dangling bonds, which can act as trap sites. Also, the presence of moisture and surface absorbates at the interface have been shown to cause variations in hysteresis due to polar molecules like water33, which can act to screen the electric field in the channel region. In addition, due to the dielectric scaling down to 10 nm, the gate bias sweep has been reduced for both devices to 2 V in comparison to other works that requires much larger gate voltages between 20 and 40 V.

Next, the photocurrent (IPH = ILIGHT − IDARK) generation between the two devices was compared by plotting the photocurrent (IPH) versus gate voltage (VG) at VDS = 150 mV and Popt = 1.5 mW cm−2 in Fig. 2e. The HfO2 device displayed a much larger peak IPH of 2.1 μA compared to the SiO2 device whose peak IPH was 62.3 nA. Here the HfO2 device provided a 33 times higher photocurrent generation compared to the SiO2 device under the same biasing and illumination conditions. After the peak photogenerated current was reached, the SiO2 device showed a decline; however, the HfO2 device still displayed detection of photocurrent even into accumulation mode. A close-up of the illumination curves from Fig. 2a, b can be seen in Fig. 2c, d. For the HfO2 device, due to the strong ID–VG parallel shifting under illumination, there is an increase in the on-state current in comparison to the dark state on-current. As a result, this device is still able to detect photocurrent in both depletion and accumulation mode operation. Conversely, the SiO2 device did not show this behavior as the illumination on-current is roughly the same as the dark condition. Lastly, the dependence of the photocurrent on the incident optical power density was plotted in a log scale in Fig. 2f. The gate voltages of −1.52 and −1 V were evaluated under depletion mode for the phototransistors and VDS was 150 mV. The photocurrent as a function of the optical power can be fitted using a power–law relationship: Iph ∝ \(P_{{\rm{opt}}}^\alpha\), where the exponent α can range from 0 < α ≤ 1. A value of 1 represents a linear relationship where the increase in photocurrent is solely due to the photogenerated carriers (photoconductive effect)34. For the case of α < 1, it indicates a sub-linear relationship due to the presence of traps, defects, and other complicated photogeneration/recombination processes20,35. From the data fitting, the HfO2 device had α = 0.82 for VG = −1.52 V and α = 0.29 for VG = −1 V. On the other hand, the SiO2 device had α = 0.94 for VG = −1.52 V and α = 1.39 for VG = −1 V. The HfO2 device maintained the expected sub-linear relationship; however, the SiO2 device showed a close to linear photocurrent relationship with increasing optical powers. As a result of the photogating effect, the HfO2 device is capable of producing 103–105 order of magnitude larger photocurrents under depletion mode versus SiO2 whose photoresponse is photoconductive in this regime.

High-temperature annealing and dielectric hole trapping

HfO2 is currently used in CMOS technology. In comparison to silicon dioxide, its use in TMDC-based transistors offers benefits, such as higher carrier densities, dielectric screening effects, and lower operating voltages. For silicon-based transistors, these types of metal oxide dielectrics have been found to have an inherent charge-trapping property36, which has been shown to have reliability issues such as degraded mobility from Coulomb and phonon scattering37,38 and threshold voltage shifts from charge injection into pre-existing traps in the high-k material39. One technique to improve the dielectric interface quality by reducing the interface trap density between the oxide and semiconductor layer is to perform a high-temperature anneal40. Here we explored the effects of thermal annealing to HfO2 and explore its impact on the photoresponse. After ALD deposition of HfO2, a rapid thermal annealing was performed at 1000 °C for 1 min before transferring MoS2. As-deposited HfO2 is amorphous; however, by applying a high-temperature anneal, it can introduce some crystalline domains to produce a polycrystalline film. An X-ray diffraction of both the amorphous and 1000 °C annealed HfO2 films can be seen in Supplementary Fig. 5. The 1000 °C HfO2 displayed some monoclinic phase peaks in its spectrum in comparison to the no anneal HfO2, which had none. The photoresponse of the 1000 °C annealed HfO2 device under the same biasing (VDS = 150 mV) and illumination conditions from before can be seen in Fig. 3a. It also displays the photogating effect; however, its illumination curves did not display strong parallel shifting like the no-anneal device. The photocurrent generation of the 1000 °C HfO2 device was also measured and plotted in Fig. 3b. Under a constant illumination of 1.5 mW cm−2, it generated a lower peak IPH of 46.7 nA.

a Photoresponse of the 1000 °C RTA annealed HfO2 phototransistor. b Photocurrent generation of the 1000 °C RTA annealed HfO2 phototransistors at 1.5 mW cm−2. c Stress and sense ID–VG measurement of HfO2 device under dark condition with VG = −2 V stress bias at various stress times. d Top: threshold voltage shift from negative bias stress (NBS). Bottom: effective defect generation from NBS.

To test the intrinsic potential of hole trapping with HfO2, a “stress and sense” I–V measurement41 was performed under the dark condition. In this measurement, a negative gate pulse of −2 V was applied under varying stress time durations of 100 ms, 1 s, 10 s, and 100 s. After each gate pulse stress, an I–V sweep around the threshold voltage was measured and plotted in Fig. 3c. The threshold voltage shift was measured with respect to the before stress threshold voltage (VTHO). As the stress time was increased, the ID–VG curves moved toward the left as a parallel shift. This negative threshold voltage shift indicates the presence of trapped hole charges. Figure 3d shows the threshold voltage shift and effective density of defects (ΔNeff) generated from the negative bias with respect to stress time. In negative bias temperature instability, ΔNeff is a term that contains the total contribution of fast and slow defect states that are generated from the applied stressing conditions42. It can be determined from \({\Delta} N_{{\rm{eff}}} = \frac{{{\Delta} V_{{\rm{TH}}}\times C_{{\rm{ox}}}}}{q},\) where ΔVTH is the threshold voltage shift, Cox is the oxide capacitance, and q is the electronic charge. The same measurement was also performed with the SiO2 device where the negative bias stress ID–VG plot can be found in Supplementary Fig. 6. Comparing the two devices, the HfO2 device showed a larger threshold voltage shift and a larger defect density in ~1012 cm−2 with increasing bias stress time. Overall, these results show that a longer negative bias stress time leads to more defects generated in the oxide layer leading to larger threshold voltage shifting.

Mechanism of photogating with HfO2

As previously discussed, the photogating mechanism relies on the charge trapping of the photogenerated holes. One method to confirm the photogating effect is to look at the amount of threshold voltage shifting under increasing optical powers. The threshold voltage shift is defined as: \({\Delta} V_{{\rm{TH}}} = V_{{\rm{TH}},\,{\rm{DARK}}} - V_{{\rm{TH}},\,{\rm{DARK}}}\). In Fig. 4a, it shows a comparison of the threshold voltage shift versus optical power density for all three devices: no anneal HfO2, SiO2, and 1000 °C HfO2. The negative sign in ΔVTH indicates the presence of trapped hole charges. The no anneal HfO2 device overall displayed a stronger threshold voltage shift compared to the other devices indicating its higher sensitivity to the photogating effect. Another method to confirm the presence of photogating is to look at the relationship between the photocurrent and transconductance. Since the photogating effect produces a shift in the threshold voltage resulting in an increase to the drain current, the photocurrent should have a proportional relationship with the transconductance based on the following approximation: \(I_{{\rm{PH}}} \approx g_m\times {\Delta} V_{{\rm{TH}}}\)28, where \(g_m = \frac{{{\rm{d}}I_{\rm{D}}}}{{{\rm{d}}V_{\rm{G}}}}\). Based on the results from Fig. 2c, we plotted the photocurrent at 1.5 mW cm−2 and the device’s transconductance as a function of the gate voltage up until the peak photocurrent in Fig. 4b, c for the HfO2 and SiO2 devices, respectively. Both devices displayed a similar trend for the photocurrent and transconductance; however, the HfO2 device showed a closer proportional relationship, thus further confirming a stronger photogating effect.

a Comparison of threshold voltage shift under illumination with no anneal HfO2, 1000 °C annealed HfO2, and SiO2 phototransistors. b Photocurrent versus VG (top) and transconductance (gm) versus VG of HfO2 device. c Photocurrent versus VG (top) and transconductance (gm) versus VG of SiO2 device. d Device structure of SiO2 interlayer as a charge-tunneling blocking layer with HfO2 dielectric to suppress hole trapping. e Photoresponse of SiO2 interlayer (3.4 nm)/HfO2 (10 nm) MoS2 phototransistor with VDS = 500 mV under the same blue light illumination with optical power densities at 4.8 μW cm−2, 50 μW cm−2, 0.32 mW cm−2, and 1.5 mW cm−2. f Model of charge-trapping mechanism from photogating effect. g Photoresponse of WSe2 phototransistor (thickness ~5 nm) using HfO2 dielectric (10 nm) with VDS = 250 mV under the same blue light illumination with optical power densities at 0.32 and 1.5 mW cm−2. h Band energy diagram of multi-layered MoS2, WSe2, and HfO2 (based on ref. 44).

Light detection occurs in depletion mode where the bands near the surface of the channel bend upwards. A model of the charge-trapping process with the HfO2 dielectric can be found in Fig. 4f. The photogeneration process of free e−/h+ occurs in the depletion region of MoS2 where the electric field from VDS assists to separate the charges. According to our proposed model, the photogenerated holes tunnel into HfO2 to occupy oxide trap levels near the valence band edge of MoS2. As a result of this hole accumulation process in HfO2, the trapped holes act as a local built-in electric field, which shifts the Fermi level in MoS2 to induce more electrons. Evidence of the presence of oxide traps can be seen from the strong horizontal ID–VG shifting under light illumination. In order to suppress the photogenerated hole trapping in HfO2, the insertion of 3.4 nm of deposited SiO2 was inserted between the MoS2 channel and HfO2 to function as an insulating tunneling barrier layer (Fig. 4d). Next, the same blue light illumination measurement as before was performed in Fig. 4e. This device now showed a more dominate photoconductive behavior, thus indicating the successful separation of the oxide traps in HfO2 with the valence band edge of MoS2.

Next, the photoresponse of a different TMDC material WSe2 was analyzed utilizing the same device structure and metal contacts. Although higher optical powers were needed to clearly observe its light detection, its photoresponse to blue light can be seen in Fig. 4g where its flake thickness was close to 5 nm. Interestingly, the WSe2 device with the same HfO2 dielectric showed a strong photoconductive behavior. To understand this discrepancy with MoS2, an energy band diagram of multi-layered MoS2, multi-layered WSe2, and HfO2 with respect to the vacuum level can be seen in Fig. 4h. The valence band maximum (VBM) of WSe2 lies at a higher energy level in comparison to MoS2 and their VBM difference was determined to be 0.4 eV. HfO2 is known to have intrinsic defects such as oxygen vacancies and interstitials43 located within the bandgap where they can serve as electron and hole traps. According to a simulation study44 with monoclinic HfO2, there is a distribution of oxygen vacancies of different charged states (positive V+, negative V−, and neutral Vo) located slightly below the mid bandgap region of HfO2. In particular, the oxygen vacancies of type V+ at 2.71 eV and Vo at 2.91 eV with respect to the valence band of HfO2 correspond to energy levels with respect to the vacuum level of 5.89 eV for V+ and 5.69 eV for Vo, which lie close in energy to the VBM of multi-layer MoS2 at −5.6 eV (monolayer MoS2 has VBM at ~5.8 eV). The phenomenon of charge tunneling relies on the potential of the barrier height and effective mass of the carrier. Although the effective hole mass for MoS2 (0.54 mo45) is heavier than WSe2 (0.36 mo45), the observed tunneling behavior for MoS2 most likely arises from the defect energy levels of the oxygen vacancies in HfO2 having good band alignment with the low-lying valence band edge of MoS2. We found the photogating effect for MoS2 to be reproducible and present in all devices made (Supplementary Table 1—all devices show high responsivity); therefore, this contributing defect state in HfO2 must be an intrinsic defect. As for the photoconductive behavior observed with WSe2, its valance band offset with these oxygen vacancies provides a trap energy-level misalignment resulting in no hole trapping and instead allows for the collection of the photogenerated hole carriers at the electrode.

Photodetection metrics

Some of the figures of merit for photodetectors such as responsivity, detectivity, photogain, and time response were evaluated for the HfO2 phototransistor. The responsivity (R) represents the conversion efficiency of the incident photon flux (input signal) into photogenerated free carriers (output signal). It is defined as \(R = \frac{{I_{{\rm{ph}}}}}{{P_{{\rm{opt}}}\times A}}\), where Iph is the photocurrent, Popt is the incident optical power density, and A is the area of the channel. Under a negative gate bias and VDS = 150 mV, the responsivity with respect to optical power density can be seen in Fig. 5a. The peak responsivity of 1.1 × 106 A W−1 was obtained under the lowest optical power of 0.33 pW. The detectivity describes the response to light (sensitivity) and the noise floor of a photodetector. The dark noise current was measured based on a previously reported technique46 where we obtained 10.6 pA Hz−1/2 at a frequency of 2 Hz, which was the lowest frequency we could experimentally obtain. Due to the low dark current of this device (avg Idark ~ 5 pA), the shot noise limit was determined to be 1.3 fA Hz−1/2 from \(I_{{\rm{shot}}} = \sqrt {2qI_{{\rm{dark}}}}\), where q is electronic charge. Next, the noise equivalent power (NEP) was calculated from \({\rm{NEP}} = \frac{{I_{{\rm{noise}}}}}{R}\), where R is the responsivity. The specific detectivity (D*) was obtained from \(D^ \ast = \frac{{\sqrt A }}{{{\rm{NEP}}}}\), where A is the area of the channel region. Figure 5b shows the specific detectivity as a function of the optical power density at different VG biasing where the highest detectivity achieved was 5.62 × 1013 Jones. A more accurate measure of the detectivity of this phototransistor can be obtained by performing a dark noise current measurement at the intrinsic bandwidth of this detector at around 3 mHz (narrow bandwidth is due to its long carrier lifetime).

a Responsivity versus optical power density at VDS = 150 mV and different VG. b Specific detectivity versus optical power density at VDS = 150 mV and different VG. c Photoswitching behavior with 30 s light pulse at 1.5 mV cm−2, VG at −1.5 V, and VDS at 150 and 500 mV. d PPC model fitting to the normalized decaying drain current (ID) after illumination at VDS = 150 and 500 mV. e Benchmarking of responsivity versus wavelength of multi-layer and monolayer MoS2 phototransistors.

The photoswitching behavior was investigated to determine its time response. The device was biased under depletion mode with VG at −1.5 V and VDS at 150 and 500 mV in Fig. 5c. The blue region indicates the on-state where the light source was turned on for a duration of 30 s. Within the first few seconds the light source is turned on, there is a rapid increase in the current due to band-to-band transitions. Next, the current transitions into a slow increase where the peak current value occurs at the moment when the light source is cut off. This slow current generation is due to the photogenerated electrons that are induced from the photogenerated hole-trapping process. After the light source is turned off, the current at first decays rapidly but then transitions into a slow decay, which is called persistent photocurrent effect (PPC)47,48. The PPC effect is the sustained conductivity after illumination and is attributed to the presence of trapped charges at the interface between the semiconductor and dielectric. The relaxation time constant can be extracted from the slowly decaying drain current (ID) by using a stretched exponential decay function: \(I_{{\rm{PPC}}}\left( t \right) = I_{\rm{o}}{\rm{e}}^{ - \left( {\frac{t}{\tau }} \right)^\beta }\) where τ is the relaxation time constant and β is the decay exponent that ranges from 0 to 1. Figure 5d shows the PPC model fitted to the decaying ID after illumination. The fitting parameters of τ and β were determined to be 312 s and 0.395 for VDS = 150 mV and 272 s and 0.326 for VDS = 500 mV, respectively. For both drain voltages, the time constants were large due to the slow de-trapping time of the oxide-trapped charges. On the other hand, the SiO2 phototransistor displayed a much faster photoswitching behavior as seen in Supplementary Fig. 7. The rise and fall times were 408 and 682 ms for VDS bias of 150 mV. The faster switching speeds and stable illumination current of the SiO2 device indicates the absence of slow deep-level traps.

Photogain is the ratio between the generated photocarrier lifetime and carrier transit time. For the case where μh ≪ μe, more electrons are collected, so the photogain can be determined by \(G = \frac{{\tau _{{\rm{photocarriers}}\,\times \mu \times V_{{\rm{DS}}}}}}{{L^2}}\), where τ is lifetime of photogenerated carriers, μ is the carrier mobility, VDS is the drain–source voltage, and L is the channel length. For VDS = 150 and 500 mV, the photogain was determined to be 9.49 × 108 and 2.76 × 109, respectively. In general, there is a tradeoff between a fast time response and high photogain, since a higher photosensitivity relies on having longer carrier lifetimes. The large photogain obtained with this device can be attributed to the slow de-trapping process of the trapped hole carriers. As previously mentioned, MoS2-based phototransistors have been demonstrated to offer very large responsivities. A benchmark of previously reported MoS2 phototransistors responsivities based on monolayer and multilayer MoS2 are summarized11,16,28,29,30,32,49 in Fig. 5e. This study offers the highest responsivity in visible light at blue and red wavelengths (1.3 × 104 A W−1). The responsivity for the NIR wavelength at 850 nm was 13.2 A W−1.

Conclusion

In summary, we developed a highly photosensitive MoS2 phototransistor using high-k metal oxide HfO2 dielectrics. Due to the valence band edge alignment of MoS2 with oxygen vacancies in HfO2, it enabled hole-trapping behavior in HfO2 resulting in generating a stronger photogating effect. By providing a valence band offset with the oxygen vacancies, a strong photoconductive behavior can be observed as in the WSe2 device case. In addition, we found providing a charge-tunneling blocking layer can help to suppress the hole-tunneling into HfO2 for MoS2 and the use of SiO2 dielectrics can also show photoconductive behavior for MoS2. For the MoS2/HfO2 device, it provided a very high responsivity of approximately 106 A W−1 and photogains in ~109. By scaling the dielectric thickness down to 10 nm, it enabled lower power operation and the ability to still optically detect thin flakes. Overall, this enhancement in the photosensitivity allows for better photodetection of weak light signals under low power operation.

Methods

Device fabrication

A bulk crystal of MoS2 was purchased from 2D semiconductors and the bulk crystal of WSe2 was purchased from GrapheneHQ. Heavily doped n-type silicon was used as the substrate and was cleaned by RCA pre-cleaning followed by HF etching. For deposition of the dielectric layer, 10 nm of ALD HfO2 (Picosun) from pre-cursors of tetrakis(ethylmethylamino)hafnium and H2O was deposited at 250 °C or 10 nm of SiO2 was thermally grown by thermal oxidation (Koyo Thermo Systems Co., LTD). Multi-layered MoS2 was obtained from exfoliating the bulk crystal using tape from Nitto Corporation. MoS2 was then transferred and patterned using a photolithography process with channel length dimensions of ~5 μm. Metal contacts of 5 nm Ti/50 nm Au was deposited by e-beam evaporation. Aluminum was deposited on the backside of silicon to provide better electrical contact for the back-gate. The final step was lift-off.

Device characterization

All measurements were performed at room temperature and under ambient conditions. For the vacuum measurements, Nagase Techno Engineering Co., Ltd Grail-408-32-B was used as the probe station and Keithley 4200 SCS was used for device measurements. A commercial blue (460 nm) and red (630 nm) 0.5 W Mid-Power Flux light-emitting diode (LED) from LED Paradise (LP-5FCIHBCT) and NIR (850 nm) from Optosupply (OSI3XNE3E1E) was used as a light source with an LED lens where the distance between the LED and sample was ~6.5 cm. Ambient condition measurements were performed using Cascade probe system (Form Factor) and Agilent 4156C Precision Semiconductor Parameter Analyzer. In order to obtain a steady-state condition for illumination measurements, the LED was turned on for 1 min before the measurement was taken and was turned off for 3–5 min before subsequent measurements were made. Time response/noise measurements were made using Agilent 33500B series waveform generator to provide the light pulse waveforms. Ametek 7270 lock-in amplifier and Femto variable-gain low-noise current amplifier (DLPCA-200) was used for the noise current measurement.

Data availability

The data supporting the findings of this study can be available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Radisavljevic, A. R., Brivio, J., Giacometti, V. & Kis, A. Single-layer MoS2 transistors. Nat. Nanotechnol. 6, 147–150 (2011).

Wang, H. et al. Integrated circuits based on bilayer MoS2 transistors. Nano Lett. 12, 4674–4680 (2012).

Bertolazzi, S., Krasnozhon, D. & Kis, A. Nonvolatile memory cells based on MoS2/graphene heterostructures. ACS Nano 7, 3246–3252 (2013).

Mouafo, L. D. N. et al. Tuning contact transport mechanisms in bilayer MoSe2 transistors up to fowler-nordheim regime. 2D Mater. 4, 015037 (2017).

Di Bartolomeo, A. et al. A WSe2 vertical field emission transistor. Nanoscale 11, 1538–1548 (2019).

Iqbal, M. W. et al. High-mobility and air-stable single-layer WS2 field-effect transistors sandwiched between chemical vapor deposition-grown hexagonal BN films. Sci. Rep. 5, 10699 (2015).

Di Bartolomeo, A. et al. Pressure-tunable ambipolar conduction and hysteresis in thin palladium diselenide field effect transistors. Adv. Funct. Mater. 29, 1902483 (2019).

Zhang, Y. et al. Broadband high photoresponse from pure monolayer graphene photodetector. Nat. Commun. 4, 1811 (2013).

Xia, F., Mueller, T., Lin, Y.-M., Valdes-Garcia, A. & Avouris, P. Ultrafast graphene photodetector. Nat. Nanotechnol. 4, 839–843 (2009).

Urich, A., Unterrainer, K. & Mueller, T. Intrinsic response time of graphene photodetectors. Nano Lett. 11, 2804–2808 (2011).

Choi, W. et al. High-detectivity multilayer MoS2 phototransistors with spectral response from ultraviolet to infrared. Adv. Mater. 24, 5832–5836 (2012).

Lee, H. S. et al. MoS2 nanosheet phototransistors with thickness-modulated optical energy gap. Nano Lett. 12, 3695–3700 (2012).

Wang, Y. et al. Solution-processed MoS2/organoleadtrihalide perovskite photodetectors. Adv. Mater. 29, 1603995 (2017).

Han, P. et al. Highly sensitive MoS2 photodetectors with graphene contacts. Nanotechnology 29, 20LT01 (2018).

Lembke, D. & Kis, A. Breakdown of high-performance monolayer MoS2 transistors. ACS Nano 6, 10070–10075 (2012).

Wu, J.-Y. et al. Broadband MoS2 field-effect phototransistors: ultrasensitive visible-light photoresponse and negative infrared photoresponse. Adv. Mater. 30, 1705880 (2018).

Xiao, P. et al. Solution-processed 3d RGO-MoS2/pyramid Si heterojunction for ultrahigh detectivity and ultra-broadband photodetection. Adv. Mater. 30, 1801729 (2018).

Miller, B. et al. Photogating of mono- and few-layer MoS2. Appl. Phys. Lett. 106, 122103 (2015).

Zhang, K. et al. A substrate-enhanced MoS2 photodetector through a dual-photogating effect. Mater. Horiz. 6, 826 (2019).

Island, J. O., Blanter, S. I., Buscema, M., Van der Zant, H. S. J. & Castellanos-Gomez, A. Gate controlled photocurrent generation mechanisms in high-gain In2Se3 phototransistors. Nano Lett. 15, 7853–7858 (2015).

Yamamoto, M., Ueno, K. & Tsukagoshi, K. Pronounced photogating effect in atomically thin WSe2 with a self-limiting surface oxide layer. Appl. Phys. Lett. 112, 181902 (2018).

Xu, H. et al. High responsivity and gate tunable graphene-MoS2 hybrid phototransistor. Small 10, 2300–2306 (2014).

Huo, N. & Konstantatos, G. Ultrasensitive all-2d MoS2 phototransistors enabled by an out-of-plane MoS2 PN homojunction. Nat. Commun. 8, 572 (2017).

Tongay, S. et al. Broad-range modulation of light emission in two-dimensional semiconductors by molecular physisorption gating. Nano Lett. 13, 2831–2836 (2013).

Zou, X. et al. A comparative study on top-gated and bottom-gated multilayer MoS2 transistors with gate stacked dielectric of Al2O3/HfO2. Nanotechnology 29, 245201 (2018).

Kufer, D. & Konstantatos, G. Highly sensitive, encapsulated MoS2 photodetector with gate controllable gain and speed. Nano Lett. 15, 7307–7313 (2015).

Buscema, M. et al. Photocurrent generation with two-dimensional van der waals semiconductors. Chem. Soc. Rev. 44, 3691–3718 (2017).

Furchi, M. M., Polyushkin, D. K., Pospischil, A. & Mueller, T. Mechanisms of photoconductivity in atomically thin MoS2. Nano Lett. 14, 6165–6170 (2014).

Perea-Lopez, N. et al. CVD-grown monolayered MoS2 as an effective photosensor operating at low-voltage. 2D Mater. 1, 011004 (2014).

Lopez-Sanchez, O., Lembke, D., Kayci, M., Radenovic, A. & Kis, A. Ultrasensitive photodetectors based on monolayer MoS2. Nat. Nanotechnol. 8, 497–501 (2013).

Tran, M. D. et al. Role of hole trap sites in MoS2 for inconsistency in optical and electrical phenomena. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 10, 10580–10586 (2018).

Yin, Z. et al. Single-layer MoS2 phototransistors. ACS Nano 6, 74–80 (2012).

Late, D. J., Liu, B., Ramakrishna Matte, H. S. S., Dravid, V. P. & Rao, C. N. R. Hysteresis in single-layer MoS2 field effect transistors. ACS Nano 6, 5635–5641 (2012).

Sze, S. M. & Ng, K. K. Physics of Semiconductor Devices 3rd edn (Wiley & Sons, 2007).

Fang, H. & Hu, W. Photogating in low dimensional photodetectors. Adv. Sci. 4, 1700323 (2017).

Gusev, E. P., D’Emic, C. D., Zafar, S. & Kumar, A. Charge trapping and detrapping in HfO2 high-k gate stacks. Microelectron. Eng. 72, 273–277 (2004).

Oates, A. S. Reliability issues for high-k gate dielectrics. In IEEE International Electron Devices Meeting 2003 38.2.1–38.2.4 (IEEE, 2003).

Zhu, W., Han, J.-P. & Ma, T. P. Mobility measurement and degradation mechanisms of MOSFETs made with ultrathin high-k dielectrics. IEEE Trans. Electron Devices 51, 98–105 (2004).

Ribes, G. et al. Review on high-k dielectrics reliability issues. IEEE Trans. Device Mater. Rel. 5, 5–19 (2005).

Zhu, W. J., Ma, T. P., Zafar, S. & Tamagawa, T. Charge trapping in ultrathin hafnium oxide. IEEE Electron Device Lett. 23, 597 (2002).

Zafar, S., Callegari, A., Gusev, E. & Fischetti, M. V. Charge trapping related threshold voltage instabilities in high permittivity gate dielectric stacks. J. Appl. Phys. 91, 9298–9303 (2003).

Fleetwood, D. M. & Schrimpf, R. D. Defects in Microelectronic Materials and Devices (CRC, 2008).

McIntyre, P. Bulk and interfacial oxygen defects in HfO2 gate dielectric stacks: a critical assessment. ECS Trans. 11, 235 (2007).

Gavartin, J. L. et al. Negative oxygen vacancies in HfO2 as charge traps in high-k stacks. IEEE Trans. Electron Devices 51, 98–105 (2004).

Wickramaratne, D., Zahid, F. & Lake, R. K. Electronic and thermoelectric properties of few-layer transition metal dichalcogenides. J. Chem. Phys. 140, 124710 (2014).

Adinolfi, V. & Sargent, E. H. Photovoltage field-effect transistors. Nature 542, 324–327 (2017).

Wu, Y.-C. et al. Extrinsic origin of persistent photoconductivity in monolayer MoS2 field effect transistors. Sci. Rep. 5, 11472 (2015).

Di Bartolomeo et al. Electrical transport and persistent photoconductivity in monolayer MoS2 phototransistors. Nanotechnology. 28, 214002 (2017).

Zhang, W. et al. High-gain phototransistors based on a CVD MoS2 monolayer. Adv. Mater. 25, 3456–3461 (2013).

Acknowledgements

This work was partly commissioned by the New Energy and Industrial Technology Development Organization (NEDO) and partly supported by NIMS Joint Research Hub Program. This work was partly conducted at the Takeda Sentanchi Supercleanroom, The University of Tokyo, supported by “Nanotechnology Platform Program” of the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (MEXT), Japan, Grant Number JPMXP09F-20-UT-0021. R.N. is supported by the Japanese Government Monbukagakusho (MEXT) scholarship. The authors would like to thank Z. Zhao and H. Tang of the University of Tokyo for their technical assistance.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

R.N. conceived and designed the research, performed the fabrication, characterization, and measurements. K.To. assisted with the fabrication. T.T. assisted with the experiments. R.N. and S.T. analyzed the mechanism. R.N. wrote the manuscript with comments from all the authors. M.T., K.Te., and S.T. supervised the project.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Peer review information Primary handling editor: John Plummer.

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Nur, R., Tsuchiya, T., Toprasertpong, K. et al. High responsivity in MoS2 phototransistors based on charge trapping HfO2 dielectrics. Commun Mater 1, 103 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43246-020-00103-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43246-020-00103-0

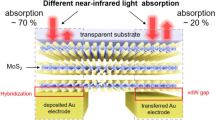

This article is cited by

-

Engineering electrode interfaces for telecom-band photodetection in MoS2/Au heterostructures via sub-band light absorption

Light: Science & Applications (2023)

-

Bioinspired in-sensor visual adaptation for accurate perception

Nature Electronics (2022)

-

Ultrahigh-responsivity waveguide-coupled optical power monitor for Si photonic circuits operating at near-infrared wavelengths

Nature Communications (2022)

-

Active pixel sensor matrix based on monolayer MoS2 phototransistor array

Nature Materials (2022)