Abstract

Growing urban population and contemporary urban systems lock-in unsustainable urban development pathways, deteriorating the living quality of urban dwellers. The systemic complexity of these challenges renders it difficult to find solutions using existing planning processes. Alternatively, transformative planning processes are radical, take place on multiple scales, and are often irreversible; therefore, require the integration of local stakeholders’ perspectives, which are often contradictory. We identify perceived levers of urban transformative change using a serious game to facilitate the integration of these perspectives through simulating neighbourhood transformation processes in two European case studies. Building on existing transformation frameworks, we organize, conceptualize, and compare the effectiveness of these levers through demonstrating their interactions with different scales of transformation. Specifically, drawing from close commonalities between large-scale (Three Spheres of Transformation) and place-based (Place-making) transformation frameworks, we show how these interactions can help to develop recommendations to unlock urban transformative change. Results show that access to participation is a key lever enabling urban transformative change. It appears to be mid-level effective to unlock urban transformative change through interactions with the political sphere of transformation and procedural element of Place-making. Ultimately, however, most effective are those levers that interact with all scales of transformation. For example, by engaging a combination of levers including access to participation, public spaces, parking, place-characteristics and place-identity. These findings could be operationalized by self-organized transformation processes focused on repurposing hard infrastructure into public spaces, whilst ensuring continuity of place-based social- and physical features. Local stakeholders could further use such processes to better understand and engage with their individual roles in the transformative process, because interactions with the personal scale, i.e., personal sphere of transformation appear paramount to unlock urban transformative change.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Growing urban population1,2,3,4 and contemporary urban systems lock-in unsustainable urban development pathways5,6,7,8, deteriorating the value of our day-to-day lives9,10. At the same time, cities are seen as important agents of change to break away from such unsustainable pathways4,8,11, whilst limiting the negative impacts on both residents and the environment12,13,14,15,16. Both political and academic discourses have embraced the need for urban transformation13, such as the New Urban Agenda from the UN-Habitat17,18, the UN Sustainable cities and communities (SDG 11)19, and the IPCC assessments20,21,22. Likewise, the EU New European Bauhaus23 calls for place-based transformation and URBACT24 highlights cities as frontrunners in these challenges. Although an exponentially growing body of research aims to inform how such urban transformation processes take shape11,13,14,15,16,25,26, only few studies assess the potential for urban transformative change by investigating factors8,13,25, drivers and barriers11,27, entry points28, and triggers of change29. To unlock urban transformative change, however, it appears paramount to identify and understand the scale, potential, and effectiveness for leverage in these processes26,30,31, which is to date not well understood8,25,32.

Transformation is widely understood as radical, fundamental, and multi-dimensional change through processes taking place on different scales of complex systems11,13,31,33,34,35,36. Central to these discussions, however, appears the interactions between scales, because these would help to identify interventions that are supposedly more or less effective to unlock transformative change. To this end, the notion of levers, Leverage Points, and the Three Spheres of Transformation have been shown instrumental to conceptualize the effectiveness of interventions for transformative change31,32,33,37,38,39,40,41,42. Leverage points are key properties of complex systems, in which focussed and comparatively small interventions – the levers43 – can leverage proportionally greater changes in the whole system42,44. Leveraging systemic change ranges from being highly effective, yet facing large resistance, to being least effective, offering only little resistance to change38,41,42,44,45,46. Drawing from the Three Spheres of Transformation and Leverage Point frameworks (Supplementary Table 1), effectiveness (low, mid-level, high) could thus be defined as the likelihood of unlocking transformative change, upon engaging a particular lever at a particular leverage point38,41,42,45,46. Adopting these frameworks as heuristic devices could help guide explorative and empirical research in a simple and comprehensive manner by harnessing interactions between scales, supporting the identification of levers leveraging transformative change31.

O’Brien’s Three Spheres of Transformation conceptualize transformative change to take place across three embedded and interacting spheres, with each sphere having differentiated effectiveness for transformative change33,41,47. The practical sphere (inner sphere, low effectiveness for transformative change) is where the outcomes of the transformation are measurable33,41, including behaviors and technical responses. The political sphere (mid-level effectiveness), encompasses the practical sphere as it defines the social and ecological systems and structures that constrain or facilitate the practical outcomes of the transformation33,41. The personal sphere (outermost sphere, high effectiveness) encompasses both the political and practical sphere, representing the individual’s worldviews, beliefs, and values, that influence which types of actions and strategies are considered possible in the political sphere, shaping the outcomes in the practical sphere33,41. To illustrate a simple, one-directional example of interactions between these spheres, one could imagine that beliefs leaning towards using bicycles rather than cars (personal sphere) would influence the discourse and resulting facilitation (political sphere) of bicycle infrastructure being realized (practical sphere). However, transformative processes are complex and deeply uncertain, generating numerous and multi-directional interactions between the spheres31,33,40,41. For example, taking-over car-based infrastructure through collective action by the Critical Mass movement (practical sphere), displays shared beliefs that influence the perception (personal sphere) of existing systems and structures by different prioritization of values (political sphere). Alternatively, people lacking meaningful urban spaces to interact with (practical sphere), are locked-into contemporary urban systems through planning processes that pre-define the design of these spaces (political sphere) hindering development of relational values to the urban environment (personal sphere). In turn, perceiving these urban systems as “given” (personal sphere), hinders individual actions that shape the urban system (practical sphere), through acknowledging those in position of power to protect the existing system (political sphere). Consequently, the Three Spheres of Transformation in conjunction with levers and leverage points can be utilized to organize, conceptualise, and compare the effectiveness of a variety of simple to very complex interactions taking place in transformation processes.

Yet, because such universal frameworks typically conceptualize large-scale transformation, they are not tailored to capture place-based knowledge, whereas urban transformative change is embedded in highly localized worldviews, beliefs, and values. Interestingly, transformations of smaller-scale (urban) systems (i.e. neighbourhoods) often form a pre-condition for fundamental transformation of its connected systems (i.e. cities, urban regions)31,39. Indeed, understanding such place-based transformation processes opens up possibilities for activating deep leverage points for transformative change10,37,38,48. The neighbourhood-scale therefore seems to be an appropriate boundary object because that is where one expects people to have most interactions with the system, as opposed to for example the city- or regional scale. The neighbourhood-scale additionally provides a level playing field where people can easily relate to and as such helps to bridge differing worldviews, beliefs, and values through finding common language and perspectives33,39. Engaging with such place-based knowledge facilitates the creation of meaningful places emerging out of a totality of individual, collective, and institutional interactions between people and their urban environment48,49. Place-making operationalizes such place-based interactions through capturing localized values, components, and culture in elements of person, place, and procedures50. Understanding these place-based elements and their interactions with large-scale transformation, helps to embed recommendations for transformative change in local worldviews, beliefs, and values.

Facilitating the exchange on such interactions therefore requires active involvement of people to integrate differing worldviews, beliefs, and values to ensure transformative change towards meaningful places51. However, when it comes to these worldviews, beliefs, and values, different people often have contradictory perspectives, and as transformative change is a process of often irreversible changes11,15, it is of fundamental importance to facilitate the integration of different perspectives. Multiple approaches with varying degrees and techniques of involving people exist52,53,54,55, yet serious games provide an engaging and fun platform to foster the negotiation of perspectives between different types of stakeholders51,53,56,57,58,59,60. More importantly, they have been used in the simulation of transitions and transformation processes61,62,63,64 because they allow for the co-creation and co-evaluation of knowledge56,65,66, learning about the systems’ complexity53,56,67,68,69,70, and help to identify place-based challenges71,72. Due to these qualities, serious games have an established track-record of being employed in urban participatory processes55,72,73,74 to help navigate the related systemic complexity52,75,76.

Based on such reflexive forms of knowledge creation77 one could identify perceived levers of transformative change. However, to define causality with real-life impacts on transformative change, one would need to link perceived levers to real-life leverage points. This is inherently difficult, because by definition of transformative change, the impact of interventions is complex and uncertain, making the operationalization of causal links inherently difficult. For example, relatively small levers at odd leverage points might result in transformative change, whereas large levers in leverage points central to the system could have limited to no-effect42. Against this backdrop, levers as defined in this work cannot be considered to have causal effects to real-life transformative change78. However, linking the perception of leverage points as identified by local experts to theoretical leverage points is still important because support for real-life interventions – the levers – hinges on diverse and divergent perceptions, epistemologies, and worldviews43 concerning transformative change. Thus, extracting experts perceptions on what enables or hinders such complex and dynamic change phenomena whilst being immersed in a local context79,80 would allow to both operationalize the leverage point perspective for exploratory research43 and identify perceived levers of urban transformative change.

In this paper, we identify a set of perceived levers, their perceived enabling or hindering potential, as well as the perceived effectiveness of this potential to unlock urban transformative change through demonstrating interactions between different scales of transformation. To this end, we design a serious game to simulate transformation processes from two contrasting examples of neighbourhood transformations in two cities and deploy transformation frameworks to harness the discussions triggered by these processes. The transformation of the neighbourhood in Hochdorf (Switzerland) is characterized by a deadlock-situation, dealing with a lack of attractiveness and liveliness, whereas the urban transformative process of the neighbourhood in Helsinki (Finland) is rapid and ongoing, yet perpetuates an unsustainable urban system facing issues of access to green space and gentrification. Based on multiple game sessions simulating these processes, levers were identified through a mixed-method analysis of empirical data arising from discussions between local urban representatives (public, private, place-based (academic) expert and civil-society) reflecting on these processes. These multi-stakeholder discussions give us insights in the scales of transformation on which people believe to have influence (i.e. practical sphere) and those that are believed to be not directly accessible (i.e. political-, personal sphere), next to showing us the role of the context on levers of urban transformative change. We operationalize Place-making to guide the discussions between local experts, based on which we identify perceived levers of transformative change, to then assess these with regards to theoretical transformation frameworks including the Three Spheres of Transformation and Leverage Points. By exploring the interactions of levers with Leverage Points, large-scale- (Three Spheres of Transformation), and place-based transformation frameworks (Place-making), we further demonstrate how these interactions can inform recommendations to unlock urban transformative change.

Results

Enabling and hindering levers of urban transformative change

Full agreement between three coders for the deductive coding category “Potential” results in a subset of participant statements (N = 266) that address enabling or hindering potential for urban transformative change. By inductively coding this set of statements, we identify five urban transformation themes: Planning Processes, Mobility, Liveliness, Spatial Allocation, and Place. For each of the five themes, we identify two to six levers of urban transformative change (Fig. 1).

Based on 266 participant statements, urban transformative change is characterized by five urban transformation themes (Planning Processes, Mobility, etc.), their corresponding levers (access to participation, agility and anticipation, etc.), the levers’ attribute reflecting the enabling or hindering potential (access to participation (open), etc.), and their salience indicated by the number of statements (access to participation (open) [N = 42], etc.).

The theme Planning Processes covers levers such as access to participation, reflecting the potential of co-creating urban development pathways, and agility and anticipation, representing the potential of contemporary planning processes to respond to short- respectively long-term urban development. Mobility mainly concerns the lever parking supply, addressing the needs for car parking spaces. For Liveliness, we find the levers retail availability (availability of (franchise-independent) shopping, services, and gastronomy) and social interaction (potential of interaction with others in public places). Spatial Allocation is composed of the levers mixed-use, referring to functionalities of the urban form; open structures, addressing its particular shape; and public spaces, representing its quality. In the case of Place, the lever place-characteristics (preservation of place-based elements into new urban development) and place-identity (place-based aesthetics as well as shared expressions of social values and meanings that make people feel an integral part of (shaping) the urban environment) emerge (see Supplementary Tables 2–6 for all themes and respective levers including exemplary participant statements).

Most salient levers, ordered by theme, include access to participation (N = 47) and agility and anticipation (N = 15); parking supply (N = 28); retail availability (N = 22) and social interaction (N = 19); mixed-use (N = 20), open structures (N = 15), and public spaces (N = 14); and place-characteristics (N = 19). Participants address the lever access to participation (open) the most as having enabling potential for urban transformative change, provided the participatory process includes all urban stakeholders to co-determine the direction of development at each stage of the planning process. However, when access to participation is perceived as closed, the participatory process is difficult to access and does not consider silent opinions, hindering the transformation. Furthermore, hard infrastructure reflected by the lever parking supply (sufficient) appears to enable transformative change if the supply of car parking is based on actual needs only and does not compete with other potential functionalities. Yet, the supply of car parking hinders the transformation when it results from pre-defined city-planning requirements or underground parking is not feasible (parking supply (necessary)).

Effectiveness of levers for urban transformative change

Based on full agreement between three coders (N = 110) on both the deductive coding categories “Potential” and “Spheres of Transformation”, we organize the interactions of levers with respect to the Three Spheres of Transformation and Leverage Points framework (Supplementary Table 1) to indicate their effectiveness for urban transformative change (Fig. 2). Access to participation remains the most dominant enabling lever (N = 18). Interacting with the political sphere, its effectiveness is lower than levers interacting with the personal sphere, but higher than those interacting with the practical sphere. However, most of the levers’ enabling potential appears least effective for transformative change, since it is related to the practical sphere (N = 58): for example, through levers such as open structures (N = 8) and retail availability (N = 9).

The span of each lever shows their identified- (bright colors) and possible- (faded colors) interactions with the Three Spheres of Transformation based on a minimum of two statements (Supplementary Table 7). The “lever potential” shows the enabling- (green) or hindering (red) potential scaled by the number of statements addressing this potential (Supplementary Figure 1). Engaging a lever symbolizes unlocking transformative change, e.g. for place-characteristics through engaging enabling interactions with the practical- and personal sphere, whilst avoiding hindering interactions with the political sphere.

Some levers interact with the practical- and personal sphere (notably public spaces) or with two adjacent spheres, such as parking supply. Yet, both levers from the theme Place, interact with all Three Spheres of Transformation. Here, the enabling potential of the lever place-characteristics (coherent) can be engaged through interactions with the practical- and personal sphere, whereas place-characteristics (restrictive) indicates hindering potential of interacting with the political sphere. Similarly, place-identity interacts with all Three Spheres of Transformation, yet place-identity (passive) mostly hinders transformative change at the personal sphere, i.e. when a place is created for, not by the people.

Embedding large-scale-into place-based transformative change

Levers appearing in the practical-, political-, and personal sphere of large-scale transformation show close similarities with those appearing in place-, procedural-, and person elements of place-based Place-making50. Most practical levers relate to the place itself, such as those alluding to the form of a place, e.g. open structures as exemplified by the participant statement: “[…] dense blocks and […] punctually some space or park [so that it] allows [for] smaller pockets within the larger area.” (Resident Association, Helsinki). Moreover, we find similarities for practical levers referring to the function and perception of a place, for example in retail availability: “[…] I want to be able to shop there, drink my coffee on Saturday morning in a fine bakery where it smells good.” (Municipality, Hochdorf). The levers appearing in the political sphere refer to procedural elements of Place-making, notably the lever access to participation: “[…] create opportunities for this kind of joint discussions [with] representatives of different parties in the planning phase in different stages.” (Housing Cooperative, Helsinki). The few times a lever appears in the personal sphere, it relates to personal feelings about a place, ergo person element of Place-making, such as in place-identity: “Children liked it terribly when it was self-made and they had ownership to it.” (Resident Association, Helsinki), or in place-characteristics: “[…] these time-honored houses […] I think it’s important that they can at least be preserved in this way - they have to be renovated, refurbished, [etc.] - but just make sure that they are preserved.” (Landowner, Hochdorf).

Based on the identified levers and agreement between at least two coders (N = 135), we compare the distributions of levers interacting with both the Three Spheres of Transformation and Place-making showing, indeed, strong commonalities between the two transformation frameworks (Supplementary Fig. 2). Parking supply, for example, interacts with both the political sphere (Three Spheres of Transformation) and procedures (Place-making): “As long as there are subsidized parking spaces, or the city plan […] requires that they are built, [it] means that the home buyer or tenant who does not have a car, subsidizes those who have [a car].” (Resident Association, Helsinki). Retail availability interacts with both the practical sphere (Three Spheres of Transformation) and place (Place-making): “There has to be something nearby where you can have a coke, a beer, or a coffee” (Housing Cooperative, Hochdorf).

Engaging levers for place-based transformative change

Participants address different levers, or address them less or more often, depending on the case study (Supplementary Table 8). This differentiation suggests place-based potential for transformative change. For example, in Hochdorf when engaging the levers accessibility, retail availability, social interaction, mixed-use, and place-characteristics. Yet, similar occurrence of levers for Hochdorf and Helsinki suggest that access to participation is the most important lever to help unlock transformative change in both cases (NHochdorf = 27, NHelsinki = 20), followed by parking supply (NHochdorf = 17, NHelsinki = 11), agility and anticipation (NHochdorf = 7, NHelsinki = 8), and place-identity (NHochdorf = 7, NHelsinki = 7).

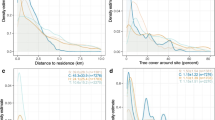

Although the simulated transformation processes are highly context-specific, the empirical data does not satisfy the basic assumptions required for simple statistical tests, such as a Pearson’s Chi-square test of independence, which would allow for testing the significance of place-based levers addressed in either Hochdorf or Helsinki (Supplementary Tables 8-9). Nevertheless, based on agreement between at least two coders, the interactions of levers with both the Three Spheres of Transformation and Place-making (N = 135) and normalizing the number of statements per case, allows to compare contextualized levers for urban transformative change on a common scale (Fig. 3).

This balloon plot shows the themes, levers and their potential to unlock urban transformative change when engaging levers through elements of Place-making in Hochdorf (CH) and Helsinki (FI). We normalize the number of participant statements (N = 135) to create a common scale, account for differing speech-preferences, and aid interpretation based on which we compare the cases. The size of the circles represents the normalized number of statements (linearly transformed to values between zero and one) and the color indicates the effectiveness to unlock urban transformative change based on the Three Spheres of Transformation- and Leverage Point frameworks (Supplementary Table 1).

Being cautious of possible counter-effects between levers having both enabling and hindering potential (Fig. 1), these results suggest that the lever access to participation has most potential to unlock transformative change when engaging it through procedural elements of Place-making in both cases. For Hochdorf specifically, unlocking transformative change appears highly effective when engaging the lever access to participation through procedural elements of Place-making and place-characteristics through elements of person and place. Following, agility and anticipation and bridging visions suggest mid-level effectiveness when engaging procedural elements of Place-making. Ultimately, because participants in Hochdorf predominantly address levers related to place, it seems important to embed the transformative process strongly in elements of place, followed by procedure, and last person. Engaging primarily with elements of place, however, has low effectiveness for transformative change. A notable exceptions is (a lack of) place-identity, which appears to exert strong hindrance for transformative change when engaging elements of place.

In the case of Helsinki, it seems that engaging access to participation through procedural elements of Place-making has largest potential to unlock transformative change, followed by agility and anticipation and public spaces. The levers access to participation and agility and anticipation seem to have mid-level effectiveness to unlock transformative change when engaging procedural elements of Place-making, whereas public spaces appears to do so with low effectiveness engaging elements of place yet high effectiveness when engaging personal elements. Overall, participants address levers that are predominantly related to procedural elements, followed by elements of place, and last person. This suggests that, contrary to Hochdorf, it is more important to embed the transformation in Helsinki strongly in elements of procedure, having mid-level effectiveness to unlock urban transformative change.

Discussion

In this research, we have identified perceived levers, their perceived enabling or hindering potential, as well as their perceived effectiveness to unlock urban transformative change by organizing, conceptualizing, and comparing their interactions with large-scale (Three Spheres of Transformation, Leverage Points) and place-based (Place-making) transformation frameworks. Our paper shows that the use of serious games is an effective approach to collect empirical data on asymmetric participant beliefs concerning complex urban transformation processes. Specifically, providing a platform for discussions between public, private, civil-society, and place-based (academic) experts, can simulate urban neighbourhood transformations in a way that facilitates a process of understanding complexity, interdependencies, and trade-offs to help identify where in the urban system there is potential to intervene and how effective this is perceived to be. We also show that participants mainly address levers interacting with the practical- and political sphere. Interestingly, participants do not often tap into the personal sphere, whereas generating rapid change requires engagement with all Three Spheres of Transformation – predominantly through levers interacting with the political- and personal sphere. This could indicate a lack of reflection about the personal role on the individual scale of urban transformation processes, which is, however, a crucial component to unlock urban transformative change. Thus, understanding how to engage levers that interact with the personal sphere, potentially activated through citizen-led participation processes, appears to be key to successful urban transformation.

Open access to participation is perceived to be a key enabling lever for large-scale urban transformative change through interactions with both the political sphere (Three Spheres of Transformation) and deep leverage points (Leverage Point framework). For place-based transformative change, one could engage this lever through procedural elements of Place-making. Results demonstrate how the concepts of levers and Leverage Points can be utilized in conjunction with large-scale (Three Spheres of Transformation) and place-based (Place-making) transformation frameworks to identify interactions within and across scales of transformation. Strong commonalities between these frameworks further hint at the possibility to explicitly link small-scale with large-scale processes of transformation. These commonalities are evident and promising because the identified levers describe meaningful interactions linking the Three Spheres of Transformation, with elements of Place-making, and Leverage point frameworks.

Participation is indeed related to transformative change within urban landscapes11,27,28,29. Yet, despite our findings indicating access to participation as a lever with enabling potential, it is also seen as both largest driver and barrier for urban transformation when trying to facilitate the integration of different perspectives between stakeholders28. Overall, however, creating opportunities for real engagement of, and collaboration between, a diverse set of stakeholders is seen as a critical driver for urban transformative change11,27,29,35. Interestingly, participants perceive that contemporary participatory processes are “[…] a kind of advertising speech. If you really want to do something, then the citizens should start doing it.” (Resident Association, Helsinki). Yet, the results show that open access to participation is governed by the political sphere – suggesting a lack of reflection on the individual or collective role in such processes31 – although citizen-led transformation processes likely tap into deep leverage points for change38, notably by having ‘the power to add, change, evolve, or self-organize system structure’ (Leverage Point four)42. Frankly, mobilizing access to participation to leverage urban transformative change should refrain from being merely a process of informing, consulting, or placation within the traditional institutional realm55. Instead, participation should also facilitate self-organized transformation processes, such as with the creation of new ‘urban commons’, that can disrupt or challenge contemporary formal planning processes28,81.

In exploring the meaningfulness of commonalities between the different frameworks, it appears relevant that access to participation interacts with the political sphere because it would allow for more direct involvement of diverse urban stakeholders to co-create the conditions for transformative change in the practical sphere41. Similarly, interactions with procedural elements of Place-making could be facilitated through either administrative or collectively organized processes50. Such co-created and collectively organized processes could in turn facilitate the creation of feedback loops by designing social structures and institutions that direct information flows to the actual users of the urban landscape (Leverage Point six)38,42. These information flows help stakeholders confront the consequences of their decisions more directly, and thereby facilitates the activation of deep leverage points for change38,42.

A striking result is that hard infrastructure such as parking, is not explicitly seen as a lever in the literature on urban transformative change. We see, however, that the necessity of car-based infrastructure drives fast-paced transformations in urban landscapes, resulting in rapidly deteriorating public spaces82. Although regulatory measures typically counter these realities, the amount of space required for such infrastructure remains a significant driver of undesired urban transformation83,84. Our findings suggest that spatial elements of parking harbor enabling potential, whereas institutional elements are perceived to hinder transformative change. In particular, the supply of parking from a sufficiency perspective (enabling), interacts predominantly with the practical sphere (low-effectiveness) and elements of place in Hochdorf (CH), whereas its supply from a necessity perspective (hindering), the political sphere (mid-level effectiveness) and procedural elements in Helsinki (CH). These considerations signal the interdependencies between different scales of transformation, but also highlight place-based differences, and the trade-offs between leveraging change through levers with low resistance and low effectiveness on the one hand, and those with higher resistance, yet larger effectiveness on the other hand. As such, it is difficult to pinpoint the silver bullet46,85,86 of unlocking (place-based) transformative change because of non-linear and uncertain chains of leverage between different scales and leverage points30,42,85,87. Removing hard infrastructure through focussing on parking from a supply-perspective could, however, be a highly relevant lever to unlock cascading urban transformative change, for example through strategies that reclaim the use of this space for purposes other than vehicles88,89, i.e. public spaces. Operationalizing this through a Place-making perspective, this could be achieved through interactions with procedural elements such as in the case of car-free city-centre policies90. Alternatively, small-scale interventions interacting with elements of place, could focus on transforming parking places into urban green space88,89 or into so called ‘parklets’, thereby promoting soft mobility91,92.

At the same time, we recognize that our findings are a product of the lens with which we approach our research39. We acknowledge that, although the need to engage with diverse worldviews, beliefs, and values in transformation processes is increasingly recognized10,31,32,34,37,44,93,94,95,96,97,98, there are already many approaches to do so within an urban context14,27,28,51,99,100,101,102, and there is a plethora of frameworks and methods available38,44,45,46,103,104,105,106,107,108,109 to capture and engage with such dynamic processes. Every approach has its drawbacks and so does ours in using serious games to foster discussions on urban transformation processes and harnessing these discussions through a mixed-method analysis linking them to theoretical transformation frameworks.

Serious games have acknowledged drawbacks, specifically their heavy reliance on assumptions to reflect real-life transformative change processes. Other problems are that a limited number of studies have formally validated their efficacy69,110,111,112,113,114,115 and that they seem to immerse participants in a full in-game reality116, which is by definition not identical to reality. Indeed, the in-game reality is a simplified representation of the transformative process, and we have not conducted a formal validation of its representativeness111,117,118. Other approaches, such as interviews or surveys, are not immersive and do not create an alternative reality but have their own drawbacks, including limited scope for gathering information52. The goal of our approach, however, is to abstract reality to then have local experts reflect on the simulated transformation process with respect to real-life transformation processes. Hence, to balance the degree of reality61,117, we have drawn from interviews, reports, surveys, location-visits, design-iterations, informal validations, and expert elicitation to design the serious games. Had we have used solely surveys or interviews; we suspect this not to have been possible.

Benefits of the serious games are clearly highlighted by the local experts participating in this research. For example, participants state that “the game itself was perhaps, or the discussion during the game, the most fruitful part” (Sustainability Expert, Helsinki), and “it was terribly refreshing to see how negotiations of this kind are progressing” (Resident Association, Helsinki). While one “kept falling back into reality” (Landowner, Hochdorf)”, and others pondered on how “to create opportunities of this kind of joint discussions with representatives of different parties in the planning phase at different stages” (Housing Cooperative, Helsinki). These examples suggest that such games could actually help bridge the gap with reality by highlighting realistic elements: “the parking problem has been quite real” (Housing Cooperative, Helsinki) or those that are un-realistic: “there should have been someone like that greedy capitalist as a character in the game because everyone was a bit touchingly unanimous” (Housing Cooperative, Helsinki). Besides, because participants draw from realistic examples to back their argumentation, it helps us understand real-life interactions with the system. It would, however, be interesting to know if other methods – also including elements of co-design, co-production and co-evaluation – would generate similar discussions concerning transformative change14,28,99,100,101,119.

One could argue that such participant statements reflect worldviews, beliefs, and values concerning individual or collective interactions with the neighbourhood system. Because participants have differentiated (epistemic) access to such interactions, they are guided by questions on Place-making to reflect on these interactions during focus-group discussions. A caveat of this approach could be that we anchor participants to think in terms of Place-making, which could introduce some bias of results. Involving two independent qualitative coders in an iterative coding-process using inter-coder reliability tests, however, counters this potential bias, next to the fact that we arrive at meaningful interactions with and close commonalities between Place-making and the Three Spheres of Transformation. Moreover, despite lacking the means to perform statistical analysis – resulting from the nature of the empirical data and drawing from a small-sample size – the results are in general agreement with existing literature (Supplementary Table 10). This is an interesting find in itself, because it seems that worldviews, beliefs, and values unveil the scales to which participants believe to have epistemic access to. This helps to unravel factors, processes, and dynamics underlying place-based transformations, besides evaluating interactions as well as their implications based on collective reflections on the outcome of the simulation13. As a consequence, we acknowledge that this approach is limited to smaller-scale system transformations (i.e. neighbourhoods). A next step could, therefore, look at explicit interactions with larger scale systems (i.e. cities, urban regions) to understand the role of neighbourhoods as agents of change13,31,39.

The degree to which we can capture the full complexity of real-life transformation processes is also limited as a result of the different concepts and frameworks deployed. For example, taking the existing mapping of the Three Spheres of Transformation- onto the Leverage Point framework at face value, one could overlook the potential effectiveness of many, small-scale, and supposedly less-effective interventions (i.e. levers interacting with the individual scale ergo practical sphere), likely also affecting transformative change at higher-order scales of the system31. Moreover, because levers are typically understood as actionable interventions37,44, levers such as place-identity and place-characteristics would not satisfy this condition directly, and the levers’ one-dimensional representation of interactions between scales fails to accurately depict more complex, non-linear, or causal interactions. Further, we tend to blur the distinction between ‘transformation’ (addressed by the outcomes with respect to the Three Spheres of Transformation and Place-making) and ‘transition’ (addressed through the concepts of levers and Leverage Points). To illustrate, transition refers mainly to the ‘how’ of change (the processes and dynamics that produce patterns of change, enabling or hindering non-linear shifts between different states of the system) and transformation refers to the ‘what’ of change (the outcomes of change at a systemic level)34. It is thus difficult to integrate different concepts and frameworks and we forgo the potential benefits of alternative perspectives and frameworks6,27,93,109,120,121. Yet, few alternative frameworks lend themselves for exploring the interactions between different scales whilst explicitly linking to methodological boundary objects such as levers and Leverage Points85,122.These, however, allow us to organize, conceptualize, and compare a variety of simple to very complex interactions taking place in transformation processes.

Aware of these limitations, our results nevertheless suggest that unlocking transformative change is most effective when individuals and groups interact with all scales of transformation41, such as with the levers place-identity and place-characteristics. The preservation of place-characteristics is indeed seen to catalyse urban transformation projects123, because the more value is given to local peculiarities, the more the urban transformation can be embedded in the local fabric124. Importantly, however, rapid urban transformation that is merely based on perpetuating physical and material aspects – disregarding place-based culture – likely facilitates the creation of homogenous places resulting from increasing globalization processes. This, in turn, creates a negative feedback cycle that further diminishes both place-based urban identities and intentions of people to engage with these places, i.e. being actively involved in shaping more meaningful and liveable places48,124,125,126,127. It thus seems crucial that place-identity, to overcome hindrances related to material artefacts of the transformation, should ensure that cultural values are reflected in particular practices and behaviors (practical sphere), norms and institutions (political sphere), and shared beliefs, values, and worldviews that influence the perception of a system and its structure (personal sphere)41,127,128. In particular, when one intends to unlock transformative change from the practical- through to the personal sphere, one has to ensure that radical changes are perceived as attractive and still familiar129, by preserving both social and physical features of a place130.

Although these results are based on difficult to control dynamic interactions117,131 between participants that reflect on simulated urban transformation processes, they show that unlocking urban transformative change involves, ultimately, self-organized transformation processes, focused on reclaiming public spaces from hard infrastructure, and the integration of place-characteristics and place-identity across all scales of transformation. Nonetheless, one should not forwent studying the potential of many, small-scale interventions (through interactions with e.g. the practical sphere) as they potentially unlock cascading effects of transformative change across higher order scales of the urban system. Although further tests are needed, strong commonalities between Place-making and the Three Spheres of Transformation further hint at the possibility to explicitly link place-based and small-scale interventions with large-scale processes of transformation, which is an important area of research highlighted in the (urban) transformation literature. In particular, because they could help to understand more complex, non-linear, or causal links between large-scale urban transformative change and its place-based operationalization. Ultimately, our results suggest that urban transformative change can be unlocked by self-organized and co-created processes that challenge the traditional institutional realm, focused on reclaiming public spaces from hard infrastructure, whilst preserving place-characteristics and place-identity (i.e. social and physical features) engaging people to interact with all scales of transformation.

Methods

Deadlock and rapid neighbourhood transformations in two European cities

Because the development and adaptation of a new serious game is resource-intensive, we select two contrasting examples of urban neighbourhood systems that are locked-in unsustainable urban development pathways. We study levers of urban transformative change by simulating deadlock (neighbourhood re-development in a state of inaction, Hochdorf (Switzerland)) and rapid (development of a new neighbourhood, Helsinki (Finland)) transformation processes (Fig. 4).

The neighbourhood in Hochdorf (CH) is locked into a stuck urban development process, because it faces issues similar to those that were defined over twenty years ago, illustrating the deadlock situation of transforming its neighbourhood. These issues are related to deteriorating retail, increasing pressure of motorized traffic, and a lack of both inviting and comfortable places to meet and linger132,133. Efforts to address this situation include the involvement of citizens through workshops and individual exchanges132, focused surveys on improving the quality of public spaces134, detailed legislative programs to guide its development135, and efforts focused on alleviating pressure of motorized traffic in the centre133.

The rapid urban development process in Helsinki (FI) is perceived to lock-in unsustainable urban pathways, because the transformation process perpetuates unsustainable urban systems, despite reflecting state-of-the-art planning practice. The rapid realisation of the neighbourhood in Helsinki is a typical example of brown-field development – repurposing underused, typically former industrial land in urban areas136 – transforming a former harbor into residential area, being in the final stages of its development (expected completion in 2023). Issues relate to a lack of access to high quality public green space, inadequate nature-based solutions, “staged” design and gentrification, and a clash between imposed SMART-technologies and actual community-needs, as identified in the SMARTer Greener Cities project137, and project-partners from the University of Helsinki, Forum Virium Helsinki, and Finnish Ministry of Environment. The City of Helsinki’s participatory budgeting services, OmaStadi, is an example of public efforts of involving citizens in its urban development strategy138, and in collaboration, the B.GREEN project coordinated by Forum Virium Helsinki, aims at co-creating green-infrastructure solutions through urban living labs, workshops, and on-site exchanges with the population139.

In sum, common characteristics between both cases include a lack of attractiveness, liveliness, and access to green space. Besides displaying differing degrees of urban transformation (deadlock vs. rapid), culture, and locations, both represent similar grades of peri-urban development, densities of urban structure, middle class residents, democratic processes, and homogenization effects of globalization processes.

Serious gaming workshops

The workshops were hosted within (Hochdorf, Brauistübli) or in close-vicinity (Helsinki, Urban Lab Kalasatama) to the selected neighbourhoods. Each of the four workshops subjected participants (urban representatives from the public and private sector, place-based (academic) experts, and civil-society) to an introduction of the EU ERC Globescape project, a serious game simulating the neighbourhood transformation, and a game debriefing in the form of a focus group discussion reflecting on the transformation process (Fig. 5). Each workshop lasted around three hours, with one-hour reserved for game-time and one for the discussion (see supplemental experimental procedures).

Seventeen local stakeholders participated voluntarily (Hochdorf: 9, Helsinki: 8) and gave informed consent for recording and analysis of their discussions, after being recruited through mail, phone calls, location visits, and the help of local public, private, and residential actors (see supplemental experimental procedures for an example invitation). The workshops (game + focus group discussion) were facilitated by the principal researcher in Hochdorf and by a Finnish project-partner in Helsinki, following a workshop protocol (see supplemental experimental procedures). This allowed us to carry out the workshops in the native language of the participants – Swiss-German in Hochdorf and Finnish in Helsinki.

Serious game description

The outcome of the game is open-ended, yet starts with a simplified representation of the current (ownership) situation within the neighbourhood, and invites four players (public, private, place-based expert, civil-society) to co-create the neighbourhood transformation during three to four turns. The game requires negotiations between players concerning costs, benefits, spatial implications, and asymmetric objectives in shaping the transformation. The neighbourhood is depicted on a square grid of cells containing generic urban elements (private and public spaces, green and blue spaces, roads, businesses, parking spaces) that represent the place-based urban structure for both neighbourhoods (Fig. 6).

The transformation is simulated through implementation of collective- (the projects) or private transformation decisions (the actions), while external effects (the events) trigger implications that relate to the chosen transformation interventions (Table 1). In each turn, a phase-indication disc guides players through four distinct phases and two indicators govern the scoring: public approval and neighbourhood appeal. The score for public approval is of main interest to the player representing the public stakeholder. The neighbourhood appeal affects the income generated from ownership of businesses – the higher the score, the more income and vice versa (phase 1: neighbourhood appeal). Ownership of businesses, parking, residential buildings, and private green spaces generate income needed to implement small- to larger scale projects and actions (phase 2: income). Implementation of projects and actions requires negotiations between the players and compliance with spatial and financial conditions within a ten-minute time restriction (phase 3: projects and actions). External events affect the score and motivate players to think about particular topics in response to the state of the transformation (phase 4: events).

Serious game conceptual simulation model

The game simulates place-based transformations within a particular neighbourhood (‘place’), its place-based elements (‘form’ and ‘function’), and the particular perception thereof (‘perception’)49. The game operationalizes Place-making – place-based transformation – by incorporating relevant urban representatives (‘person’), simulating transformation processes (‘procedures’), to arrive at a place-specific outcome (‘place’)50 – a particular instantiation of the transformation (Fig. 7).

Four players operationalize Place-making while seated around the tabletop game in a manner that mimics the power-knowledge interactions by placing the public representative closer to the (information concerning the) projects as opposed to the other players. Each player’s individual perception of this representation – the person element – forms the basis for the negotiations with the other players. Having the potential to implement projects and actions governs the procedural element, and the resulting instantiation of the neighbourhood transformation is a place-based outcome of Place-making.

Mixed-method analysis of focus group discussions

Levers of urban transformation were identified through a qualitative data analysis of participant statements from the focus group discussion reflecting on the simulated transformation process. The analysis progressed through two coding cycles. The first coding cycle103 organizes the statements using deductive coding categories103,104 and the second cycle characterizes these statements with inductive coding categories Fig. 8.

Two native speakers and project-independent coders were involved to iteratively develop a coding protocol104,140 (see SupplementaryMethods), establish a solid understanding of the deductive coding categories through inter coder reliability (ICR) tests103,104,141,142,143, and perform structural coding to organize the empirical data-corpus. The principal coder pre-selected relevant statements from the transcripts as input for the first coding cycle, kept analytical memo’s to help devise inductive coding categories, and performed manual coding and qualitative analysis in the second coding cycle to identify the levers of transformation (Table 2).

Materials availability

The available materials include both physical versions of the serious game and all its game-elements. We are happy to arrange for its use, but have to discuss on a case-by-case basis concerning conditions of use of the game-materials currently stored in Zürich (Switzerland).

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Research Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

The empirical data sets including participant statements and corresponding qualitative codes are publicly available on Zenodo under the following identifier: https://zenodo.org/records/10351899.

Code availability

The Rmarkdown script used for the quantitative analysis and visualizations is publicly available on Zenodo under the following identifier: https://zenodo.org/records/10351899.

References

Binder, C. R., Wyss, R. & Massaro, E. General Introduction. in Sustainability Assessment of Urban Systems (eds. Binder, C. R., Massaro, E. & Wyss, R.) 1–4 (Cambridge University Press, 2020).

Dodman, D., McGranahan, G., Dalal-Clayton, D. B., & International Institute for Environment and Development (IIED)). Integrating the environment in urban planning and management: key principles and approaches for cities in the 21st century. (2013).

United Nations. World Population Prospects 2019: Highlights. https://www.un.org/development/desa/pd/sites/www.un.org.development.desa.pd/files/files/documents/2020/Jan/wpp2019_highlights.pdf (2019).

Urban Planet: Knowledge towards Sustainable Cities. (Cambridge University Press, 2018).

Seto, K. C. et al. Carbon lock-in: types, causes, and policy implications. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 41, 425–452 (2016).

Geels, F. W. The multi-level perspective on sustainability transitions: Responses to seven criticisms. Env. Innov. Societal Transitions 1, 24–40 (2011).

Dorst, H., van der Jagt, A., Runhaar, H. & Raven, R. Structural conditions for the wider uptake of urban nature-based solutions – A conceptual framework. Cities 116, (2021).

Romero-Lankao, P. et al. Urban transformative potential in a changing climate. Nature Clim Change 8, 754–756 (2018).

Westman, L. & Castán Broto, V. Urban transformations to keep all the same: the power of ivy discourses. Antipode 54, 1320–1343 (2022).

McPhearson, T. et al. Radical changes are needed for transformations to a good Anthropocene. npj Urban Sustain 1, 5 (2021).

McCormick, K., Anderberg, S., Coenen, L. & Neij, L. Advancing sustainable urban transformation. J. Cleaner Prod. 50, 1–11 (2013).

Perspectives on Urban Sustainability. In Sustainability Assessment of Urban Systems (eds. Binder, C. R., Massaro, E. & Wyss, R.) 239–350 (Cambridge University Press, 2020).

Hölscher, K. & Frantzeskaki, N. Perspectives on urban transformation research: transformations in, of, and by cities. Urban Transform 3, 2 (2021).

Nevens, F., Frantzeskaki, N., Gorissen, L. & Loorbach, D. Urban Transition Labs: co-creating transformative action for sustainable cities. J. Cleaner Prod. 50, 111–122 (2013).

Elmqvist, T. et al. Sustainability and resilience for transformation in the urban century. Nat. Sustain 2, 267–273 (2019).

Wolfram, M. & Frantzeskaki, N. Cities and systemic change for sustainability: prevailing epistemologies and an emerging research agenda. Sustainability 8, 144 (2016).

UN-Habitat. World Cities Report 2016: Urbanization and Development - Emerging Futures. https://unhabitat.org/world-cities-report-2016 (2016).

UN-Habitat. World Cities Report 2022: Envisaging the Future of Cities. https://unhabitat.org/sites/default/files/2022/06/wcr_2022.pdf (2022).

United Nations. The Sustainable Development Goals Report 2019. https://digitallibrary.un.org/record/3812145 (2019).

IPCC. Fact sheet - Cities and Settlements by the Sea. https://www.ipcc.ch/report/ar6/wg2/downloads/outreach/IPCC_AR6_WGII_FactSheet_CitiesSettlementsBtS.pdf (2022).

IPCC. The 6th IPCC Report and what it means for cities. IUCN https://www.iucn.org/news/water/202203/6th-ipcc-report-and-what-it-means-cities (2022).

Revi, A. Urban Areas. 535–612 https://www.ipcc.ch/site/assets/uploads/2018/02/WGIIAR5-Chap8_FINAL.pdf (2014).

EU. New European Bauhaus. Transformation of places on the ground calls 2023-2024 https://new-european-bauhaus.europa.eu/get-involved/funding-opportunities/transformation-places-ground-calls-2023-2024_en (2022).

EU. URBACT. https://urbact.eu/ (2002).

Wolfram, M., Frantzeskaki, N. & Maschmeyer, S. Cities, systems and sustainability: status and perspectives of research on urban transformations. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 22, 18–25 (2017).

Grêt-Regamey, A. et al. Harnessing sensing systems towards urban sustainability transformation. npj Urban Sustain 1, 1–9 (2021).

Kroh, J. Sustain(able) urban (eco)systems: Stakeholder-related success factors in urban innovation projects. Technol. Forecasting Social Change 168, 120767 (2021).

Radywyl, N. & Biggs, C. Reclaiming the commons for urban transformation. J. Cleaner Prod. 50, 159–170 (2013).

Mendizabal, M., Heidrich, O., Feliu, E., García-Blanco, G. & Mendizabal, A. Stimulating urban transition and transformation to achieve sustainable and resilient cities. Ren. Sustain. Energy Rev. 94, 410–418 (2018).

Palomo, I. et al. Assessing nature-based solutions for transformative change. One Earth 4, (2021).

O’Brien, K. et al. Fractal approaches to scaling transformations to sustainability. Ambio 52, 1448–1461 (2023).

Horcea-Milcu, A.-I. Values as leverage points for sustainability transformation: two pathways for transformation research. Current Opin. Environ. Sustain. 57, 101205 (2022).

O’Brien, K. & Sygna, L. Responding to climate change: The three spheres of transformation. Proceedings of the Conference Transformation in a Changing Climate 16–23 (2013).

Hölscher, K., Wittmayer, J. M. & Loorbach, D. Transition versus transformation: What’s the difference? Environ. Innov. Soc. Trans. 27, 1–3 (2018).

Ernst, L., de Graaf-Van Dinther, R. E., Peek, G. J. & Loorbach, D. A. Sustainable urban transformation and sustainability transitions; conceptual framework and case study. J. Cleaner Prod. 112, 2988–2999 (2016).

Feola, G. Societal transformation in response to global environmental change: A review of emerging concepts. Ambio 44, 376–390 (2015).

Chan, K. M. A. et al. Levers and leverage points for pathways to sustainability. People Nat. 2, 693–717 (2020).

Abson, D. J. et al. Leverage points for sustainability transformation. Ambio 46, 30–39 (2017).

Leventon, J., Abson, D. J. & Lang, D. J. Leverage points for sustainability transformations: nine guiding questions for sustainability science and practice. Sustain. Sci. 16, 721–726 (2021).

O’Brien, K. Global environmental change II: From adaptation to deliberate transformation. Progr. Human Geogr. 36, 667–676 (2012).

O’Brien, K. Is the 1.5 °C target possible? Exploring the three spheres of transformation. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 31, 153–160 (2018).

Meadows, D. Leverage Points: Places to Intervene in a System. 18 (1999).

Riechers, M., Fischer, J., Manlosa, A. O., Ortiz-Przychodzka, S. & Sala, J. E. Operationalising the leverage points perspective for empirical research. Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability 57, (2022).

Koskimäki, T. Places to intervene in a socio‐ecological system: A blueprint for transformational change | Signed in. (2021) https://doi.org/10.3390/su13169474.

Nobles, J. D., Radley, D. & Mytton, O. T. The Action Scales Model: A conceptual tool to identify key points for action within complex adaptive systems. Perspect Public Health (2021).

Birney, A. How do we know where there is potential to intervene and leverage impact in a changing system? The practitioners perspective. Sustain. Sci. 16, 749–765 (2021).

Sharma, M. Personal to Planetary Transformation. (2007).

Grêt-Regamey, A. & Galleguillos-Torres, M. Global urban homogenization and the loss of emotions. Sci. Rep. 12, 22515 (2022).

Switalski, M. & Grêt-Regamey, A. Operationalising place for land system science. Sustain. Sci. 16, 1–11 (2021).

Switalski, M., Torres, M. G. & Grêt-Regamey, A. The 3P’s of place-making: Measuring place-making through the latent components of person, procedures and place. Landsc. Urban Planning 238, 104817 (2023).

Seve, B., Redondo, E. & Sega, R. A Taxonomy of Bottom-Up, Community Planning and Participatory Tools in the Urban Planning Context. ACE: Arch. City Environ. 16, 18 (2021).

Voinov, A. et al. Tools and methods in participatory modeling: Selecting the right tool for the job. Environ. Model. Softw. 109, 232–255 (2018).

Ampatzidou, C. et al. All Work and No Play? Facilitating serious games and gamified applications in participatory urban planning and governance. UP 3, 34–46 (2018).

Prilenska, V. Current Research Vectors in Games for Public Participation in Planning. (2020).

Arnstein, S. R. A Ladder Of Citizen Participation. J. Am. Inst. Planners 35, 216–224 (1969).

Piňos, J. Current trends in using serious games and video games in teh field of urban planning. Cartogr. Lett. 27, 11 (2019).

Ouariachi, T. Facilitating multi-stakeholder dialogue and collaboration in the energy transition of municipalities through serious gaming. Energies 14, 3374 (2021).

Billger, M., Thuvander, L. & Wästberg, B. S. In search of visualization challenges: The development and implementation of visualization tools for supporting dialogue in urban planning processes. Environment and Planning B: Urban Analytics and City. Science 44, 1012–1035 (2017).

Klamert, K. & Münster, S. Child’s Play - A Literature-Based Survey on Gamified Tools and Methods for Fostering Public Participation in Urban Planning. in Electronic Participation (eds. Parycek, P. et al.) vol. 10429 (Spinger, Cham., 2017).

Bruley, E. et al. Actions and leverage points for ecosystem-based adaptation pathways in the Alps. Environ. Sci. Policy 124, 567–579 (2021).

Lorig, F. et al. An Agent-based Approach for Simulating Transformation Processes of Socio-ecological Systems as Serious Game. Interaction Des. Arch. 31, 98–114 (2016).

Gugerell, K. & Zuidema, C. Gaming for the energy transition. Experimenting and learning in co-designing a serious game prototype. J. Cleaner Prod. 169, 105–116 (2017).

Ampatzidou, C. & Gugerell, K. Mapping Game Mechanics for Learning in a Serious Game for the Energy Transition. Int. J. E-Planning Res. 8, 1–23 (2019).

Lanezki, M., Siemer, C. & Wehkamp, S. “Changing the Game—Neighbourhood”: An Energy Transition Board Game, Developed in a Co-Design Process: A Case Study. Sustainability 12, 10509 (2020).

Poplin, A., Andrade, B. & deSena, Í. Geogames for change: Cocreating the future of cities with games. In Games and Play in the Creative, Smart and Ecological City (Routledge, 2020).

Kim, D. Y., Pietsch, M. & Uhrig, N. Local knowledge acquisition using gamification for the public participation process. GIS-Zeitschrift fü Geoinformatik 33, 113–121 (2020).

Sterman, J. Interactive web-based simulations for strategy and sustainability: The MIT Sloan LearningEdge management flight simulators, Part II. Syst. Dyn. Rev. 30, 206–231 (2014).

Sterman, J. D. Learning in and about complex systems. Syst. Dyn. Rev. 10, 291–330 (1994).

Bakhanova, E., Garcia, J. A., Raffe, W. L. & Voinov, A. Targeting social learning and engagement: What serious games and gamification can offer to participatory modeling. Environ. Model. Softw. 134, 104846 (2020).

Olejniczak, K., Newcomer, K. E. & Meijer, S. A. Advancing Evaluation Practice With Serious Games. Am. J. Evaluat. 41, 339–366 (2020).

Salliou, N. et al. Game of Cruxes: co-designing a game for scientists and stakeholders for identifying joint problems. Sustain. Sci. 16, 1563–1578 (2021).

Devisch, O., Poplin, A. & Sofronie, S. The gamification of civic participation: two experiments in improving the skills of citizens to reflect collectively on spatial issues. J. Urban Technol. 23, 81–102 (2016).

Prilenska, V., Liias, R. & Paadam, K. Games in Communicative Planning: A Comparative Study. (2015).

Poplin, A. Playful public participation in urban planning: A case study for online serious games. Comput. Environ.Urban Syst. 36, 195–206 (2012).

Bhardwaj, P., Joseph, C. & Bijili, L. Ikigailand: Gamified Urban Planning Experiences For Improved Participatory Planning.: A gamified experience as a tool for town planning. in IndiaHCI ’20: Proceedings of the 11th Indian Conference on Human-Computer Interaction 104–108 (Association for Computing Machinery, 2020).

Ataman, C. & Tuncer, B. Urban Interventions and Participation Tools in Urban Design Processes: A Systematic Review and Thematic Analysis (1995 – 2021). Sustain. Cities Soc. 76, 103462 (2022).

Woiwode, C. et al. Inner transformation to sustainability as a deep leverage point: fostering new avenues for change through dialogue and reflection. Sustain. Sci. 16, 841–858 (2021).

Lynam, T., de Jong, W., Sheil, D., Kusumanto, T. & Evans, K. A Review of Tools for Incorporating Community Knowledge, Preferences, and Values into Decision Making in Natural Resources Management. Ecol. Soc. 12, (2007).

Casula, M., Rangarajan, N. & Shields, P. The potential of working hypotheses for deductive exploratory research. Qual. Quant. 55, 1703–1725 (2021).

Schalbetter, L., Salliou, N., Sonderegger, R. & Grêt-Regamey, A. From board games to immersive urban imaginaries: Visualization fidelity’s impact on stimulating discussions on urban transformation. Comp. Environ. Urban Syst. 104, 102003 (2023).

Christiansen, L. D. The Timing and Aesthetics of Public Engagement: Insights from an Urban Street Transformation Initiative. J. Planning Educ. Res. 35, 455–470 (2015).

Gogishvili, D. Competing for space in Tbilisi: transforming residential courtyards to parking in an increasingly car-dependent city. Eurasian Geog. Econ. 0, 1–27 (2021).

Childs, M. C. Parking spaces: a design, implementation, and use manual for architects, planners, and engineers. (McGraw-Hill, 1999).

Shoup, D. High Cost of Free Parking. (Routledge, 2011). https://doi.org/10.4324/9781351179539.

Fischer, J. & Riechers, M. A leverage points perspective on sustainability. People Nat. 1, 115–120 (2019).

Ostrom, E. A diagnostic approach for going beyond panaceas. PNAS 104, 15181–15187 (2007).

Angheloiu, C. & Tennant, M. Urban futures: Systemic or system changing interventions? A literature review using Meadows’ leverage points as analytical framework. Cities 104, 102808 (2020).

Cilliers, E. J. & Timmermans, W. Transforming spaces into lively public open places: case studies of practical interventions. J. Urban Design 21, 836–849 (2016).

Croeser, T. et al. Finding space for nature in cities: the considerable potential of redundant car parking. npj Urban Sustain 2, 1–13 (2022).

Nederveen, A. A. J., Sarkar, S., Molenkamp, L. & Van de Heijden, R. E. C. M. Importance of Public Involvement: A Look at Car-Free City Policy in The Netherlands. Transp. Res. Record 1685, 128–134 (1999).

Campisi, T., Caselli, B., Rossetti, S. & Torrisi, V. The evolution of sustainable mobility and urban space planning: exploring the factors contributing to the regeneration of car parking in living spaces. in vol. 60 (Elsevier B.V., 2022).

Shahani, F., Pineda-Pinto, M. & Frantzeskaki, N. Transformative low-carbon urban innovations: Operationalizing transformative capacity for urban planning. Ambio (2021).

Moore, M.-L. et al. Studying the complexity of change: toward an analytical framework for understanding deliberate social-ecological transformations. E&S 19, art54 (2014).

IPBES. Summary for policymakers of the methodological assessment of the diverse values and valuation of nature of the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES). https://zenodo.org/record/7410287 (2022).

Fisher, E., Brondizio, E. & Boyd, E. Critical social science perspectives on transformations to sustainability. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 55, 101160 (2022).

Monstadt, J., Colen Ladeia Torrens, J., Jain, M., Macrorie, R. M. & Smith, S. R. Rethinking the governance of urban infrastructural transformations: a synthesis of emerging approaches. Current Opin. Environ. Sustain. 55, 101157 (2022).

Lam, D. P. M. et al. Scaling the impact of sustainability initiatives: a typology of amplification processes. Urban Transform. 2, 3 (2020).

Linnér, B.-O. & Wibeck, V. Drivers of sustainability transformations: leverage points, contexts and conjunctures. (2021) https://doi.org/10.1007/s11625-021-00957-4.

Huning, S., Räuchle, C. & Fuchs, M. Designing real-world laboratories for sustainable urban transformation: addressing ambiguous roles and expectations in transdisciplinary teams. Sustain Sci 16, 1595–1607 (2021).

Cognetti, F. Beyond a Buzzword: Situated Participation Through Socially Oriented Urban Living Labs. In Urban Living Lab for Local Regeneration: Beyond Participation in Large-scale Social Housing Estates (eds. Aernouts, N., Cognetti, F. & Maranghi, E.) 19–37 (Springer International Publishing, 2023).

Newton, P. & Frantzeskaki, N. Creating a national urban research and development platform for advancing urban experimentation. Sustain. (Switzerland) 13, 1–18 (2021).

Patel, Z. The potential and pitfalls of co-producing urban knowledge: Rethinking spaces of engagement. Methodol. Innov. 15, 374–386 (2022).

Saldaña, J. The Coding Manual for Qualitative Researchers. The Coding Manual for Qualitative Researchers 1–440 (2021).

Mayring, P. Qualitative content analysis: theoretical foundation, basic procedures and software solution. (2014).

Flick, U. An introduction to qualitative research, 4th ed. xxi, 505 (Sage Publications Ltd, 2009).

Corbin, J. & Strauss, A. Basics of Qualitative Research: Techniques and Procedures for Developing Grounded Theory. (SAGE Publications, 2014).

Bowen, G. A. Document Analysis as a Qualitative Research Method. Qual. Res. J. 9, 27–40 (2009).

Estrada, S. Qualitative Analysis Using R: A Free Analytic Tool. TQR 22, 956–968 (2017).

Parris, H., Sorman, A. H., Valor, C., Tuerk, A. & Anger-Kraavi, A. Cultures of transformation: An integrated framework for transformative action. Environ. Sci. Policy 132, 24–34 (2022).

Rodela, R., Ligtenberg, A. & Bosma, R. Conceptualizing Serious Games as a Learning-Based Intervention in the Context of Natural Resources and Environmental Governance. Water 11, 245 (2019).

Verburg, P. H. et al. Methods and approaches to modelling the Anthropocene. Global Environ. Change 39, 328–340 (2016).

Poplin, A., Kerkhove, T., Reasoner, M., Roy, A. & Brown, N. Serious Geogames for Civic Engagement in Urban Planning: Discussion based on four game prototypes. in (2017).

Stanitsas, M., Kirytopoulos, K. & Vareilles, E. Facilitating sustainability transition through serious games: A systematic literature review. J. Cleaner Prod. 208, 924–936 (2019).

Flood, S., Cradock-Henry, N. A., Blackett, P. & Edwards, P. Adaptive and interactive climate futures: systematic review of ‘serious games’ for engagement and decision-making. Environ. Res. Lett. 13, 063005 (2018).

Keijser, X. et al. Stakeholder Engagement in Maritime Spatial Planning: The Efficacy of a Serious Game Approach. Water 10, 724 (2018).

Solinska-Nowak, A. et al. An overview of serious games for disaster risk management – Prospects and limitations for informing actions to arrest increasing risk. Int. J. Disaster Risk Red. 31, 1013–1029 (2018).

Lukosch, H. K., Bekebrede, G., Kurapati, S. & Lukosch, S. G. A Scientific Foundation of Simulation Games for the Analysis and Design of Complex Systems. Simul. Gaming 49, 279–314 (2018).

Edwards, P. et al. Tools for adaptive governance for complex social-ecological systems: a review of role-playing-games as serious games at the community-policy interface. Environ. Res. Lett. 14, 113002 (2019).

Webb, R. et al. Enabling urban systems transformations: co-developing national and local strategies. Urban Transform. 5, 5 (2023).

Geels, F. W. Technological transitions as evolutionary reconfiguration processes: a multi-level perspective and a case-study. Res. Policy 31, 1257–1274 (2002).

Van Mierlo, B. et al. Reflexive Monitoring in Action. A guide for monitoring system innovation projects. (2010).

Riechers, M. et al. Key advantages of the leverage points perspective to shape human-nature relations. Ecosyst. People 17, 205–214 (2021).

de Broekert, C. Adaptive Re-use of Industrial Heritage in Dutch Post-industrial Urban Area Development: The relation of the adaptive reuse and the added value in regards to the economic, social, and environmental sustainability. (2022).

Sepe, M. Urban transformation, socio-economic regeneration and participation: two cases of creative urban regeneration. Int. J. Urban Sustain. Dev. 6, 20–41 (2014).

Al Naim, M. A. Urban Transformation in the City of Riyadh: A Study of Plural Urban Identity. Open House Int. 38, 70–79 (2013).

Beyhan, S. G. & Gürkan, Ü. C. Analyzing the Relationship Between Urban Identity and Urban Transformation Implementations in Historical Process: the Case of Isparta. Int. J. Arch. Res. 9, 158–180 (2015).

Sepe, M. & Pitt, M. The characters of place in urban design. Urban Des Int 19, 215–227 (2014).

Southworth, M. & Ruggeri, D. Beyond placelessness, place identity and the global city. in Companion to Urban Design (Routledge, 2011).

von Wirth, T., Grêt-Regamey, A., Moser, C. & Stauffacher, M. Exploring the influence of perceived urban change on residents’ place attachment. J. Environ. Psychol. 46, 67–82 (2016).

Reese, G., Oettler, L. M. S. & Katz, L. C. Imagining the loss of social and physical place characteristics reduces place attachment. J. Environ. Psychol. 65, 101325 (2019).

Freese, M., Lukosch, H., Wegener, J. & König, A. Serious games as research instruments – Do’s and don’ts from a cross-case-analysis in transportation. Eur. J.Transp. Infrastr. Res. 20, 103–126 (2020).

Gemeinderat Hochdorf. Entwicklungsplan Zentrum. https://www.hochdorf.ch/public/upload/assets/754/Zentrumsentwicklung_Entwicklungsplan_light.pdf?fp=1 (2011).

Kanton Luzern Dienststelle Verkehr und Infrastruktur (vif) & Gemeinde Hochdorf. Umfahrung Hochdorf - Zweckmässigkeitsbeurteilung ZMB - Phase 1. https://vif.lu.ch/-/media/VIF/Dokumente/kantonsstrassen/projekte/planung_studien/luzern_nordost/umfahrung_hochdorf/umfahrung_hochdorf_zmb_phase1.pdf (2021).

Gemeinde Hochdorf. Freiraumkonzept Gemeinde Hochdorf. https://www.hochdorf.ch/public/upload/assets/2145/freiraumkonzept_0920_interaktiv_v2.pdf?fp=1 (2020).

Gemeinde Hochdorf. Legislaturprogramm 2018 - 2024. https://www.hochdorf.ch/public/upload/assets/541/Legislaturprogramm_Hochdorf_2018-20241546858658495.pdf (2018).

Rey, E., Laprise, M. & Lufkin, S. Urban Brownfields: Origin, Definition, and Diversity. In Neighbourhoods in Transition: Brownfield Regeneration in European Metropolitan Areas (eds. Rey, E., Laprise, M. & Lufkin, S.) 7–45 (Springer International Publishing, 2022).

Nyberg, E., Tiitu, M., Nieminen, H. & Vierikko, K. Socio-ecological structure in Kuninkaantammi and Kalasatama study sites. https://smartergreenercities.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/Smarter_Greener_Cities_WP3_power_report2021_Nordforsk_updated_17062022.pdf (2020).

City of Helsinki. OmaStadi. The Helsinki of dreams is created together. OmaStadi. https://omastadi.hel.fi/?locale=en (2020).

Forum Virium Helsinki. B.GREEN. Adapting Neighborhoods to Be Ready for Climate Change https://bgreen-project.eu/ (2020).

Curry. Fundamentals of Qualitative Research Methods: Data Analysis (Module 5). (2015).

O’Connor, C. & Joffe, H. Intercoder Reliability in Qualitative Research: Debates and Practical Guidelines. Int. J. Quall. Meth. 19, 1609406919899220 (2020).

Skjott Linneberg, M. & Korsgaard, S. Coding qualitative data: a synthesis guiding the novice. Qual. Res. J. 19, 259–270 (2019).

Friese, D. S. ATLAS.ti 8 Mac - Inter-Coder Agreement Analysis. (2020).

Helsinki. Helsinki Map Service. Helsinki Map Service https://kartta.hel.fi/?setlanguage=en (2022).

Google. Google Maps. Google Maps https://www.google.com/maps (2022).

ATLAS.ti Scientific Software Development GmbH. (2022).

R Core Team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. (2022).

Acknowledgements