Abstract

Intense terahertz pulses offer unique pathway to resonantly drive the correlated spin systems up to the nonlinear regime. However, detection of such nonlinear spin dynamics often suffers from the small signal amplitude that can be easily hindered by the linear background components. In order to efficiently extract the nonlinear signals, here we demonstrate that magnetooptical effect can be utilized. We excite spin precession in orthoferrite YFeO3 by the magnetic field of intense terahertz pulse and probe its dynamics by transient transmissivity change in the near infrared. The observed waveforms contain quasi-ferromagnetic-mode magnon oscillation and its second harmonics with a comparably strong amplitude. The result can be explained by dielectric function derived from magnetorefractive Hamiltonian. We reveal that the strong second harmonic signal microscopically originates from the dynamics of the quasi-ferromagnetic mode magnon at nonlinear regime, wherein spin canting angle periodically oscillates.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Control of spin dynamics at ultrafast time scales has been one of the central topics in modern magnetism research. Excitation by femtosecond laser pulses drastically changes intrinsic magnetic properties such as net magnetization, exchange and anisotropy1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10. Terahertz (THz) pulses offer unique advantage that their magnetic fields can excite spin dynamics resonantly at femto- to picosecond time scales while avoiding unwanted electronic and lattice heating due to its low photon energy11,12,13,14,15,16,17. Since the advancement of the intense THz light sources in the last decade, coherent THz pulses with peak electric- and magnetic fields in the order of MV/cm and ~1 Tesla has become available18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25. Sufficiently intense THz magnetic fields can induce spin dynamics up to the nonlinear regime, wherein fruitful information on the microscopic magnetic interactions and spin textures in a variety of strongly correlated spin systems and phase transition materials can be attained26,27. For example, recent works report macroscopic control of magnetization13,14,25, magnon softening28 and magnon-induced terahertz second harmonic generation29,30 to name a few.

The capability of the selective and strong excitation of spin systems is a clear advantage of THz pulses compared to the visible- to near-infrared pumping, wherein the incoherent excitation of electronic and lattice systems with much higher energies simultaneously occurs and hinders subtle signals arising from the pure nonlinear spin dynamics. However, even by the state-of-the-art table-top THz sources, the induced spin deviation angles remain in a relatively small range in most cases (typically around ~1 degree14,17,30). This makes the observation of such nonlinear spin dynamics especially challenging when linear spin responses dominate the detected signals. Therefore, the establishment of experimental and theoretical methodologies to precisely extract the nonlinear signals is expected to be of great importance.

To tackle this problem, we focus on the probing scheme. In the intense THz-pump optical probing experiment of spin systems, the magnetization dynamics M(t) is mostly detected by magnetooptical Faraday- and Kerr effects31,32,33 or magnetic dichroism34. These effects are based on the off-diagonal components of the complex dielectric permittivity tensor, which have proportional or odd-order dependences with respect to the induced magnetization change (M2N-1, N = integer) as derived by Onsager35,36,37 from the arguments based on time-reversal symmetry and energy conservation. On the other hand, the diagonal components of the permittivity tensor are of even order (M2N)35,36,37. This term gives rise to the so-called quadratic magnetorefractive effects, wherein the induced magnetization causes optical birefringence or absorption4,38,39. Magnetorefractive effect induced by THz magnonic excitation has been previously reported in NiO by measuring the polarization change of the probe pulse30. In this case, however, the polarization rotation was dominated by the linear magnetooptical Faraday effect and the magnetooptical signal was orders of magnitude smaller. In contrast, by measuring the transmissivity change of a probe pulse, it is expected that the change of a diagonal component of the dielectric permittivity can be selectively detected while avoiding the influence of magnetooptical effects arising from the off-diagonal counterpart. By this way, a precise extraction of the nonlinear spin dynamics with quadratic field-dependence can be made possible due to the intrinsic nonlinear dependence of the magnetorefractive effect. The usage of the magnetorefractive effect from the viewpoint of improving the detection sensitivity of nonlinear spin dynamics in THz magnonics has not been achieved to the best of our knowledge.

In this work, we study the THz-induced nonlinear magnetorefractive effect by probing the transmissivity change. We excite the quasi-ferromagnetic magnon mode in orthoferrite YFeO3 by the intense THz magnetic field and detect its dynamics by the transmissivity change of a near-infrared probe pulse. As a result, the transient transmissivity signal shows a strong second harmonic oscillation of the originally excited magnon mode at comparable amplitude with the fundamental mode. Through both the numerical simulation and analytical calculation, we show that the second harmonics signal can be explained by taking into account the phenomenological Hamiltonian representing magnetorefractive interaction between the sublattice spins and the probe electromagnetic fields. It indicates a new type of nonlinear motion of the quasi-ferromagnetic magnon mode where the canting angle between sublattice spins periodically changes at twice the precession frequency, possibly suggesting its nonlinear mixing with the other magnon mode, the quasi-antiferromagnetic oscillation.

Results

Experimental setup

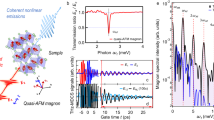

We study a single crystal of the orthoferrite YFeO3. Orthoferrite is a typical weak ferromagnet, in which antiferromagnetically ordered sublattice spins are slightly canted due to Dzyaloshinskii-Moriya interaction and result in a net magnetization M40,41,42,43. Orthoferrites exhibit orthorhombically distorted crystal structure D2h16-Pbnm40. At room temperature, the spin configuration forms the so called Γ4 phase, wherein sublattice spins align parallel to the a-axis and the magnetization M along c-axis [Fig. 1a]. Orthoferrites possess two isolated magnon modes in the sub-THz frequency region11,44,45,46,47,48,49. One is the quasi-ferromagnetic mode (qFM), which corresponds to precessional motion of the total magnetization M. The other one is called the quasi-antiferromagnetic mode (qAFM), which can be viewed as the oscillation of the vector length of M. The qFM and qAFM have different selection rules in terms of polarization. The qFM is excited by magnetic field when BTHz ⊥ M, that is BTHz // a or b at room temperature. The qAFM is excited by BTHz // M, that is BTHz // c. The resonance frequencies of the F- and AF modes in YFeO3 are fqFM = 0.3 THz and fqAFM = 0.53 THz at room temperature10. The sample is c-plane cut and have the thickness of approximately 100 μm.

a Experimental setup. The blue and red arrows indicate the sublattice magnetizations S1,2 and net magnetization M, respectively. RT Room temperature, BPD Balanced photodetector, LIA lock-in amplifier. b Typical waveform of the THz electric field measured with electrooptic sampling in a GaP (110) single crystal with 400 μm thickness. c Fourier spectrum of b.

Our experimental setup is schematically illustrated in Fig. 1a. The intense THz pulses are generated by optical rectification in LiNbO3 crystal using wave front tilting technique using Ti:Sapphire regenerative amplifier14,20. The resulted THz transient has a single-cycle waveform and a spectrum covering 0–1.8 THz, as shown in Fig. 1b, c. The terahertz magnetic field is linearly polarized parallel to BTHz // b, and the amplitude of the THz pulse is varied by two wire grid polarizers. Part of the regenerative amplifier output are mechanically delayed and used as probe pulses. In order to cancel out the intensity fluctuations of the light source and obtain sufficient signal to noise ratio, we employ balanced photodetection by splitting the probe pulse into two paths and measuring the difference (dT) between the pulses transmitted through the sample (T) and the reference which is directly sent into the other photodiode. The probe pulse EP is linearly polarized parallel to the crystal a-axis, unless otherwise stated. All measurements are performed at room temperature (See Methods section for further experimental details).

Experimental result

Figure 2a shows the transient transmissivity waveforms dT/T measured in YFeO3 at incident electric field amplitudes of 110 kV/cm, 165 kV/cm, and 220 kV/cm. The THz pulses are incident at t = 0 ps, which is marked by a sharp peak. This signature increases quadratically with the incident field, and is ascribed to a third-order optical nonlinearity due to the incident THz electric field50. In the region t > 0 ps, an oscillation at a period of 3.3 ps is observed. This period matches that of the qFM magnon at fqFM = 0.3 THz and indicate that this oscillation originates from the precession of the total magnetization M around c-axis. The envelope function shows an increase after pumping and does not exhibit decay with a simple exponential function as contrasted to the spin dynamics conventionally observed by THz transmission spectroscopy11,44,46. This characteristic feature is frequently observed in the spin dynamics of orthoferrites under THz excitation. It is ascribed to the electromagnetic interaction between propagating magnon modes and the incident THz magnetic field. Detailed investigation of this feature is provided in previous works such as refs. 51,52, and is therefore not the main scope of the present work.

a Transient transmissivity change dT/T induced by THz excitation in YFeO3 sample under various THz field strengths. b Fourier spectrum of a normalized to the peak at 0.3 THz. c Spectral amplitudes of 0.3 THz and 0.6 THz peaks as functions of incident THz field strength. Fitting curves with linear (0.3 THz) and quadratic (0.6 THz) dependence are also plotted.

The waveform is strongly dependent on the incident field strength. Under the strong THz excitation amplitudes, the waveform becomes highly asymmetric. In this regime, there appears an additional oscillatory signature that is synchronized with the original qFM but is half the period. As can be seen in the Fourier spectra in Fig. 2b, this oscillation has a frequency at 0.6 THz, which precisely matches the second harmonic (SH) of fqFM = 0.3 THz. It also clearly differs from the other magnon mode qAFM, which sets in at 0.53 THz11, indicating that it originates from the qFM dynamics. The field dependence of the spectral peaks at 0.3 THz and 0.6 THz are plotted in Fig. 1c. The 0.3 THz peak is linearly dependent with the incident THz field, while the 0.6 THz peak scales quadratically. The appearance of the second-harmonic signal is also observed in a different orthoferrite ErFeO3 (Supplementary Note A). Both the fundamental and the second harmonic oscillations are observed only when the probe pulse is polarized along Ep // a (Supplementary Note B).

Theoretical calculation based on Magnetorefractive effect

In order to understand the mechanism of the observed second harmonics signal in detail, we perform numerical calculation of the spin dynamics based on two-sublattice model which is commonly used to describe orthoferrites41,42. Substituting the calculated spin dynamics into the time-dependent dielectric permittivity function derived from magnetorefractive interaction between the spins and the probe electric field, we reproduce the experimentally measured second-harmonics signals.

First, we consider the Hamiltonian of the Fe3+ spins as:

where z = 6 is the number of nearest neighboring Fe3+ sites, JFe = 4.96 meV and DFe = 0.107 meV are isotropic and antisymmetric exchange interaction strengths, respectively, and Ax;z;xz are the magnetic anisotropy energies (Ax = 0.00288 meV, Az = 0.0008 meV, Axz = 0 meV). Each parameter is adjusted from the literature values (14,53,54,55) to reproduce the qFM and qAFM resonance frequencies of YFeO3 at room temperature. The equation of motion of Sj=1,2 for the Hamiltonian including external magnetic flux Bext(t) is expressed as:

where g is the g-factor, μB is the Bohr magneton, and γ = gμB/ħ is the gyromagnetic ratio.

In order to describe the quadratic magnetorefractive effect observed experimentally, we consider the following form of Hamiltonian representing nonlinear interaction between the spin dynamics and the electric field of probe light:4,38

Here, Eξ is the electric field in the ξ = {x, y, z} direction. αξ,ξ’ and βξ,ξ’ are coefficients for the isotropic and antisymmetric exchange interactions that connect the electric field Eξ and the spins \({{{{\boldsymbol{S}}}}}_{{{\mathrm{1,2}}}}\). This Hamiltonian phenomenologically originates from the virtual transition of O2-–Fe3+ charge transfer4 (Supplementary Note C). We can rewrite Eq. (3) in the form of dielectric permittivity tensor as:

From Eqs. (3) and (4), the change of permittivity induced by the spin dynamics can be deduced as

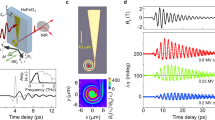

The spin dynamics numerically calculated from Eqs. (1) and (2) are plotted in Fig. 3. The blue and red curves Mx and My correspond to the x- and y-components of the macroscopic magnetization \({{{\boldsymbol{M}}}}={{{{\boldsymbol{S}}}}}_{1}+{{{{\boldsymbol{S}}}}}_{2}\), respectively, excited by a THz magnetic field pulse (black dotted waveform BTHz) with a central frequency of 0.5 THz and a peak amplitude of 0.1 T, mimicking the experimental waveform. Calculated Mx and My show clear sinusoidal oscillations at the fundamental frequency fqFM = 0.30 THz with their phase shifted by 90 degrees from each other, indicating that the dynamics of the individual spins S1,2 is dominated by a linear response of the qFM precession. Substituting the calculated spin dynamics into Eq. (4), as shown by the yellow curve in Fig. 3, we obtain the transient change of dielectric function \(\delta {\varepsilon }_{x,x}\equiv {{{\rm{Im}}}}\left[{\varepsilon }_{x,x}\left(t\right)-{\bar{\varepsilon }}_{x,x}\right]\), where \({\bar{\varepsilon }}_{x,x}\) is the equilibrium permittivity without the THz pulse. Since in our experiment only the a-polarized probe was found sensitive to the spin dynamics [Supplementary Note B], we take \({{{\rm{Im}}}}\left[{\alpha }_{x,x}\right]\) and \({{{\rm{Im}}}}\left[{\beta }_{x,x,z}\right]\) as the most relevant components in the permittivity tensor that are observable. The ratio of \({{{\rm{Im}}}}\left[{\alpha }_{x,x}\right]\) and \({{{\rm{Im}}}}\left[{\beta }_{x,x,z}\right]\) was tuned at \(|{{{\rm{Im}}}}\left[{\alpha }_{x,x}\right]/{{{\rm{Im}}}}\left[{\beta }_{x,x,z}\right]|=2\times {10}^{4}\) to reproduce the experimentally observed amplitude ratio between the fundamental and second harmonic signals at maximum incident THz field strength in Fig. 2c. In contrast to the original spin dynamics Mx and My, the induced permittivity change exhibits a clear asymmetric waveform, reproducing the experimental observation. In this way, the quadratic response is well reproduced by the nonlinear magnetorefractive interaction introduced in Eq. (3).

Discussion

In order to investigate the clearly asymmetric permittivity change in further detail, we break down the yellow curve in Fig. 3 into the separate constituent terms in Eq. (4), i.e., the isotropic term \(\delta \left({{{{\boldsymbol{S}}}}}_{1}\left(t\right)\cdot {{{{\boldsymbol{S}}}}}_{2}\left(t\right)\right)={\bar{{{{\boldsymbol{S}}}}}}_{1}\cdot \delta {{{{\boldsymbol{S}}}}}_{2}\left(t\right)+\delta {{{{\boldsymbol{S}}}}}_{1}\left(t\right)\cdot {\bar{{{{\boldsymbol{S}}}}}}_{2}+\delta {{{{\boldsymbol{S}}}}}_{1}\left(t\right)\cdot \delta {{{{\boldsymbol{S}}}}}_{2}\left(t\right)\) and the antisymmetric one \(\delta \left({{{{\boldsymbol{S}}}}}_{1}\left(t\right)\times {{{{\boldsymbol{S}}}}}_{2}\left(t\right)\right)={\bar{{{{\boldsymbol{S}}}}}}_{1}\times \delta {{{{\boldsymbol{S}}}}}_{2}\left(t\right)+\delta {{{{\boldsymbol{S}}}}}_{1}\left(t\right)\times {\bar{{{{\boldsymbol{S}}}}}}_{2}+\delta {{{{\boldsymbol{S}}}}}_{1}\left(t\right)\times \delta {{{{\boldsymbol{S}}}}}_{2}\left(t\right)\). \({\bar{{{{\boldsymbol{S}}}}}}_{{{\mathrm{1,2}}}}\) and \(\delta {{{{\boldsymbol{S}}}}}_{{{\mathrm{1,2}}}}\left(t\right)\) represent the equilibrium- and dynamical-components of the sublattice spins, respectively. The results are plotted as violet and green curves in Fig. 3. For the antisymmetric term, we plot only the z-component which is the most dominant among all three spatial axes by orders of magnitude. Figure 3 shows that the antisymmetric term \(\delta \left({{{{\boldsymbol{S}}}}}_{1}\left(t\right)\times {{{{\boldsymbol{S}}}}}_{2}\left(t\right)\right)\) contains mostly the linear (\(\omega\)) component. On the other hand, the isotropic term \(\delta \left({{{{\boldsymbol{S}}}}}_{1}\left(t\right)\cdot {{{{\boldsymbol{S}}}}}_{2}\left(t\right)\right)\) is dominated by the second harmonic (\(2\omega\)) component. These results can be understood by the fact that the equilibrium and dynamical components [\({\bar{{{{\boldsymbol{S}}}}}}_{{{\mathrm{1,2}}}}\) and \(\delta {{{{\boldsymbol{S}}}}}_{{{\mathrm{1,2}}}}\left(t\right)\)] are perpendicular to each other during the qFM precession.

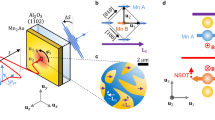

The presence of a finite amplitude of the isotropic term \(\delta \left({{{{\boldsymbol{S}}}}}_{1}\left(t\right)\cdot {{{{\boldsymbol{S}}}}}_{2}\left(t\right)\right)\) gives us an interesting insight into the nonlinear spin dynamics and magnon–magnon interactions. In the limit of linear response, the spins’ canting angle \({\beta }_{0}\) remains fixed during the qFM precession in orthoferrites41, and hence \(\delta \left({{{{\boldsymbol{S}}}}}_{1}\left(t\right)\cdot {{{{\boldsymbol{S}}}}}_{2}\left(t\right)\right)\) = 0. In contrast to such conventional picture of the qFM trajectory, our result clearly shows that the relative angle between the sublattice spins \({{{{\boldsymbol{S}}}}}_{1}\) and \({{{{\boldsymbol{S}}}}}_{2}\) periodically oscillates at twice the precession frequency during the qFM dynamics, when the precession amplitude becomes large. Taking this effect into account, a modified dynamics of qFM derived from the calculated waveforms Mx, My and εxx is schematically illustrated in Fig. 4. When both spins S1 and S2 are in the x-z plane (Fig. 4a, c), the canting angle is π - 2β0, the same as its equilibrium value. As the precession evolves and the total magnetization directs towards either +y or -y axis, the canting angle slightly increases (Fig. 4b, d). Because the spins tilt along the y axis twice during a cycle, the canting angle oscillates with double the precession frequency, leading to the observed second harmonics through magnetorefractive effect.

Each panel corresponds to t = 1.6 ps a, t = 2.5 ps b, t = 3.3 ps c, and t = 4.1 ps d in Fig. 3.

Theoretically, the periodic canting dynamics in qFM revealed above can be also interpreted as the nonlinear mixing of qFM magnon with the other magnon mode, qAFM. By analytically calculating the spin dynamics up to second order perturbation (Supplementary Note D–F), it can be derived that a term that is quadratic to the qFM amplitude can be a driving force for the qAFM dynamics, whereas qFM itself cannot be excited by such a term. These results indicate that within the second order perturbation, qFM and qAFM are coupled with each other and the second harmonic of the qFM amplitude excites the qAFM. Since qAFM is a mode wherein a periodic change of the canting angle occurs even under the limit of linear response, it can result in the appearance of the second harmonics of qFM in magnetorefractive signals through finite \({{{{\boldsymbol{S}}}}}_{1}\left(t\right)\cdot {{{{\boldsymbol{S}}}}}_{2}\left(t\right)\) term.

Conclusions

To conclude, we have excited the qFM magnon in the orthoferrites YFeO3 and ErFeO3 and measured the transient transmissivity change in the near infrared. The qFM magnon dynamics and its second harmonic have been observed with comparable amplitudes. The second harmonic dynamics are reproduced by taking into account the magnetorefractive interaction between the sublattice spins and the probe electromagnetic fields. From quantitative numerical calculation, it has been shown that the sublattice spin angle, which has been commonly assumed fixed during the qFM precession, oscillates at its second harmonic frequency, suggesting possible mixing of qFM and qAFM at large precession amplitude. The scheme of THz pump–magnetorefractive probing demonstrated here paves way for selectively detecting the coherently excited nonlinear spin dynamics and magnetooptical effects in various correlated spin systems in the future.

Methods

Experimental details

The single crystal samples of orthoferrite used in this study are grown by floating-zone method at the Materials Synthesis Section of the Institute for Solid State Physics, The university of Tokyo. The light source used in the experiment for the generation of the intense THz pulses is a Ti:Sapphire regenerative amplifier (Legend Elite from Coherent inc.), which has central wavelength at 800 nm, pulse width of approximately 100 fs, repetition rate at 1 kHz, and pulse energy of 5 mJ. The pump pulse for the THz generation is mechanically chopped at 500 Hz, and the probe signal is demodulated via a lock-in amplifier. By this way, transmissivity change dT/T is measured. The sample magnetization is saturated by a Nd magnet prior to the experiment.

Theoretical calculation

The detailed analytical calculations of the spin dynamics up to the second-order perturbation is shown in complete form in the Supplementary Information. Supplementary Notes c–e summarize the definition of the relevant parameters such as spin- and magnetorefractive Hamiltonian, coordinate axes and other reduced coefficients, along with the first-order perturbation calculation results of resonance modes which precisely agree with the conventional representations of magnon system in orthoferrite. In Supplementary Note F, we extend the spin dynamics calculation up to the second order perturbation regime, where it is shown that there appears a term in the spin equation of motion that can be represented as the excitation of 1 qAFM by 2 qFM magnons, as mentioned in the Discussion part of the main text.

Data availability

The datasets generated in the present study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Koopmans, B. et al. Explaining the paradoxical diversity of ultrafast laser-induced demagnetization. Nat. Mater. 9, 259–265 (2010).

Yamaguchi, K., Kurihara, T., Watanabe, H., Nakajima, M. & Suemoto, T. Dynamics of photoinduced change of magnetoanisotropy parameter in orthoferrites probed with terahertz excited coherent spin precession. Phys. Rev. B 92, 064404 (2015).

Afanasiev, D., Zvezdin, A. K. & Kimel, A. V. Laser-induced shift of the Morin point in antiferromagnetic DyFeO3. Opt. Express 23, 23978–23984 (2015).

Mikhaylovskiy, R. V. et al. Ultrafast optical modification of exchange interactions in iron oxides. Nat. Commun. 6, 8190 (2015).

Mikhaylovskiy, R. V. et al. Resonant pumping of d-d crystal field electronic transitions as a mechanism of ultrafast optical control of the exchange interactions in iron oxides. Phys. Rev. Lett. 125, 157201 (2020).

Fitzky, G., Nakajima, M., Koike, Y., Leitenstorfer, A. & Kurihara, T. Ultrafast control of magnetic anisotropy by resonant excitation of 4f electrons and phonons in Sm0.7Er0.3FeO3. Phys. Rev. Lett. 12710, 107401 (2021).

Tzschaschel, C. et al. Ultrafast optical excitation of coherent magnons in antiferromagnetic NiO. Phys. Rev. B 95, 174407 (2017).

Li, T. et al. Femtosecond switching of magnetism via strongly correlated spin–charge quantum excitations. Nature 496, 69–73 (2013).

Mochizuki, M. & Nagaosa, N. Theoretically predicted picosecond optical switching of spin chirality in multiferroics. Phys. Rev. Lett. 105, 147202 (2010).

Tzschaschel, C., Satoh, T. & Fiebig, M. Tracking the ultrafast motion of an antiferromagnetic order parameter. Nat. Commun. 10, 1–6 (2019).

Yamaguchi, K., Nakajima, M. & Suemoto, T. Coherent control of spin precession motion with impulsive magnetic fields of half-cycle terahertz radiation. Phys. Rev. Lett. 105, 237201 (2010).

Suemoto, T., Nakamura, K., Kurihara, T. & Watanabe, H. Magnetization-free measurements of spin orientations in orthoferrites using terahertz time domain spectroscopy. Appl. Phys. Lett. 107, 042404 (2015).

Schlauderer, S. et al. Temporal and spectral fingerprints of ultrafast all-coherent spin switching. Nature 569, 383–387 (2019).

Kurihara, T. Macroscopic magnetization control by symmetry breaking of photoinduced spin reorientation with intense terahertz magnetic near field. Phys. Rev. Lett. 120, 2018, https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.120.107202

Wienholdt, S., Hinzke, D. & Nowak, U. THz switching of antiferromagnets and ferrimagnets. Phys. Rev. Lett. 108, 247207 (2012).

Kovalev, S. et al. Selective THz control of magnetic order: new opportunities from superradiant undulator sources’. J. Phys. Appl. Phys. 51, 114007 (2018).

Kampfrath, T. et al. Coherent terahertz control of antiferromagnetic spin waves. Nat. Photon 5, 31–34 (2011).

Hebling, J., Yeh, K.-L., Hoffmann, M. C., Bartal, B. & Nelson, K. A. Generation of high-power terahertz pulses by tilted-pulse-front excitation and their application possibilities. J. Opt. Soc. Am. B 25, B6 (2008).

Fülöp, J. A., Pálfalvi, L., Almási, G. & Hebling, J. Design of high-energy terahertz sources based on optical rectification. Opt. Express 18, 12311 (2010).

Hirori, H., Doi, A., Blanchard, F. & Tanaka, K. Single-cycle terahertz pulses with amplitudes exceeding 1 MV/cm generated by optical rectification in LiNbO3. Appl. Phys. Lett. 98, 091106 (2011).

Junginger, F. et al. Nonperturbative interband response of a bulk InSb semiconductor driven off resonantly by terahertz electromagnetic few-cycle pulses. Phys. Rev. Lett. 109, 147403 (2012).

Shalaby, M. & Hauri, C. P. Demonstration of a low-frequency three-dimensional terahertz bullet with extreme brightness. Nat. Commun. 6, 5976 (2015).

Junginger, F. et al. Single-cycle multiterahertz transients with peak fields above 10 MV/cm. Opt. Lett. 35, 2645 (2010).

Sell, A., Leitenstorfer, A. & Huber, R. Phase-locked generation and field-resolved detection of widely tunable terahertz pulses with amplitudes exceeding 100 MV/cm. Opt. Lett. 33, 2767–2769 (2008).

Kurihara, T. et al. Reconfiguration of magnetic domain structures of ErFeO3 by intense terahertz free electron laser pulses. Sci. Rep. 10, 7321 (2020).

Mashkovich, E. A. et al. Terahertz optomagnetism: nonlinear THz excitation of GHz spin waves in antiferromagnetic FeBO3. Phys. Rev. Lett. 123, 157202 (2019).

Baierl, S. et al. Nonlinear spin control by terahertz-driven anisotropy fields. Nat. Photonics 10, 715–718 (2016).

Mukai, Y., Hirori, H., Yamamoto, T., Kageyama, H. & Tanaka, K. Nonlinear magnetization dynamics of antiferromagnetic spin resonance induced by intense terahertz magnetic field. N. J. Phys. 18, 013045 (2016).

Lu, J. et al. Coherent two-dimensional terahertz magnetic resonance spectroscopy of collective spin waves. Phys. Rev. Lett. 118, 207204 (2017).

Baierl, S. et al. Terahertz-driven nonlinear spin response of antiferromagnetic nickel oxide. Phys. Rev. Lett. 117, 197201 (2016).

Bennett, H. S. & Stern, E. A. Faraday effect in solids. Phys. Rev. 137, A448–A461 (1965).

Robinson, C. C. Electromagnetic theory of the Kerr and the Faraday effects for oblique incidence. JOSA 54, 1220–1224 (1964).

Keller, N. et al. Magneto-optical Faraday and Kerr effect of orthoferrite thin films at high temperatures. Eur. Phys. J. B - Condens. Matter Complex Syst. 21, 67–73 (2001).

van der Laan, G. et al. Experimental proof of magnetic x-ray dichroism. Phys. Rev. B 34, 6529–6531 (1986).

Onsager, L. Reciprocal relations in irreversible processes. I. Phys. Rev. 37, 405–426 (1931).

Onsager, L. Reciprocal relations in irreversible processes. II. Phys. Rev. 38, 2265–2279 (1931).

S. Sugano and N. Kojima, Eds., Magneto-Optics. Berlin Heidelberg: Springer-Verlag, 2000. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-662-04143-7

Subkhangulov, R. R. et al. All-optical manipulation and probing of the d–f exchange interaction in EuTe. Sci. Rep. 4, 4368 (2014).

Oh, D. G., Kim, J. H., Shin, H. J., Choi, Y. J., & Lee, N. Anisotropic and nonlinear magnetodielectric effects in orthoferrite ErFeO3 single crystals. Sci. Rep., 10, Art., (2020), https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-68800-x

White, R. L. Review of recent work on the magnetic and spectroscopic properties of the rare‐earth orthoferrites. J. Appl. Phys. 40, 1061–1069 (1969).

Herrmann, G. F. Resonance and high frequency susceptibility in canted antiferromagnetic substances. J. Phys. Chem. Solids 24, 597–606 (1963).

Herrmann, G. F. Magnetic resonances and susceptibility in orthoferrites. Phys. Rev. 133, A1334–A1344 (1964).

Wood, D. L., Remeika, J. P. & Kolb, E. D. Optical spectra of rare‐earth orthoferrites. J. Appl. Phys. 41, 5315–5322 (1970).

Zhou, R. et al. Terahertz magnetic field induced coherent spin precession in YFeO3. Appl. Phys. Lett. 100, 061102 (2012).

Jin, Z. et al. Single-pulse terahertz coherent control of spin resonance in the canted antiferromagnet YFeO3, mediated by dielectric anisotropy. Phys. Rev. B 87, 094422 (2013).

Kim, T. H. et al. Magnetization states of canted antiferromagnetic YFeO3 investigated by terahertz time-domain spectroscopy. J. Appl. Phys. 118, 233101 (2015).

Amelin, K. et al. Terahertz absorption spectroscopy study of spin waves in orthoferrite YFeO3 in a magnetic field. Phys. Rev. B 98, 174417 (2018).

Kim, T. H. et al. Coherently controlled spin precession in canted antiferromagnetic YFeO3 using terahertz magnetic field. Appl. Phys. Express 7, 093007 (2014).

Yamaguchi, K., Kurihara, T., Minami, Y., Nakajima, M. & Suemoto, T. Terahertz time-domain observation of spin reorientation in orthoferrite ErFeO3 through magnetic free induction decay. Phys. Rev. Lett. 110, 137204 (2013).

Sajadi, M., Wolf, M. & Kampfrath, T. Terahertz-field-induced optical birefringence in common window and substrate materials. Opt. Express 23, 28985–28992 (2015).

Watanabe, H., Kurihara, T., Kato, T., Yamaguchi, K. & Suemoto, T. Observation of long-lived coherent spin precession in orthoferrite ErFeO 3 induced by terahertz magnetic fields. Appl. Phys. Lett. 111, 092401 (2017).

Grishunin, K. et al. Terahertz magnon-polaritons in TmFeO3. ACS Photonics 5, 1375–1380 (2018).

Koshizuka, N. & Hayashi, K. Raman scattering from magnon excitations in RFeO3. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn 57, 4418–4428 (1988).

Gorodetsky, G. Exchange constants in orthoferrites YFeO3 and LuFeO3. J. Phys. Chem. Solids 30, 1745–1750 (1960).

Li, X. et al. Observation of Dicke cooperativity in magnetic interactions. Science 361, 794–797 (2018).

Acknowledgements

This work has been funded by the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS) KAKENHI (20K22478, 21K14550 and 20H02206). The single crystals of orthoferrite used in the study have been grown using facilities in Materials Synthesis Section at ISSP, The University of Tokyo. We thank Prof. H. Mino at Chiba Univ. for the insightful discussions.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

T.K. conceived the experimental idea, performed measurement and wrote manuscript. M.B. performed theoretical calculation and wrote the manuscript together with T.K. H.W and M.N. constructed the THz generation setup and have grown the orthoferrite samples used in the study. T.S. supervised the project together with T.K. and M.B.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Physics thanks Guo-Hong Ma and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kurihara, T., Bamba, M., Watanabe, H. et al. Observation of terahertz-induced dynamical spin canting in orthoferrite magnon by magnetorefractive probing. Commun Phys 6, 51 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s42005-023-01167-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s42005-023-01167-3

This article is cited by

-

Terahertz-field-driven magnon upconversion in an antiferromagnet

Nature Physics (2024)

-

Extreme terahertz magnon multiplication induced by resonant magnetic pulse pairs

Nature Communications (2024)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.