Abstract

Recent experiments have shown that the complex spatio-temporal vortex structures emerging in active fluids are susceptible to weak geometrical constraints. This observation poses the fundamental question of how boundary effects stabilize a highly ordered pattern from seemingly turbulent motion. Here we show, by a combination of continuum theory and experiments on a bacterial suspension, how artificial obstacles guide the flow profile and reorganize topological defects, which enables the design of bacterial vortex lattices with tunable properties. To this end, the continuum model is extended by appropriate boundary conditions. Beyond the stabilization of square and hexagonal lattices, we also provide a striking example of a chiral, antiferromagnetic lattice exhibiting a net rotational flow, which is induced by arranging the obstacles in a Kagome-like array.

Similar content being viewed by others

Active systems, both living (bacterial suspensions, cytoskeletal extracts, motility assays, cell tissues1,2,3,4,5) and inanimate (driven granular disks and rods6,7, colloidal swimmers, rollers, and spinners8,9,10,11, etc.) exhibit remarkably complex spatio-temporal collective behavior, see ref. 12 for a recent review. While the effect of confinement and boundary conditions is fairly well understood in equilibrium systems, it is mostly unexplored in active matter, with only a few theoretical and experimental studies appearing in recent years13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20.

In particular, regular bacterial flow spirals and “vortices” are reported in refs. 13,14,21,22. The observed states are characterized by neighboring vortices rotating spontaneously in the same (ferromagnetic) or opposite direction (antiferromagnetic), resembling magnetic spin lattices. The stabilization of such structures and related vortex patterns in an otherwise turbulent bacterial suspension is achieved by imposing strong confinement in an ordered array of coupled flow chambers. It came as a surprise when recent experiments19 involving a periodic array of small pillars, which covered only a few percent of available space, produced a drastic impact on an otherwise turbulent Bacillus subtilis suspension1,23,24,25. Namely, square-like vortex lattices with long-range antiferromagnetic ordering were observed19 when the lattice constant was close to the characteristic vortex size in the unconstrained system. In contrast to refs. 13,14,21, where the vortex patterns are imposed by the confinement itself, here, the emergent structures are stabilized by the weak constraints given by the pillars.

In this work, we combine a continuum description of turbulent bacterial motion25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35 with experimental study of the confinement effects in bacterial suspensions19 to answer the following fundamental questions: What are the minimal ingredients to stabilize a certain flow pattern in an active suspension? What is the impact of pillar size? And what type of lattices can occur? In particular, can the obstacle arrays be used to stabilize exotic vortex lattices with novel flow properties, such as a non-zero average vorticity and edge currents?

As a key concept, we examine, both theoretically and experimentally, the topological charges of the defects located at the pillars as a means to characterize the flow fields that surround the obstacles. By tuning the charge and the lattice constant(s) of the array relative to the intrinsic vortex size in the unconstrained suspension, we demonstrate the emergence of different types of vortex lattices, such as a chiral structure made up of two sizes of bacterial vortices. It yields a pronounced circulation on a length scale much larger than the individual vortex size.

Results

Continuum model

We employ a coarse-grained continuum description25,27,30,31,32,33,34,35, where the dynamics of the bacterial suspension is described by the effective bacterial velocity v. This phenomenological model has first been introduced in refs. 25,26, combining the Toner–Tu equation for polar active fluids36 with the complex Swift–Hohenberg equation for pattern formation37. A derivation starting from a generic Langevin model has been presented in refs. 31,32. The resulting dynamic equation reads in the dimensionless form

where q(x, t) is a Lagrange multiplier (effective pressure) enforcing the incompressibility condition ∇⋅v = 0. The parameters a, b, and λ are related to the microscopic parameters of the swimmers, e.g., swimming speed, volume fraction, and rotational relaxation time31,32. For a suspension of highly motile swimmers of type pusher, e.g., B. subtilis, as used in the experiments19, we have a > 027,31. This leads to a finite-wavelength-instability of the stationary, homogeneous, isotropic solution (v = 0). The instability is characterized by a critical wavenumber kc = 1 (see Supplementary Note 1 and refs. 26,31,32,33 for details). The coefficient of the cubic nonlinear term in Eq. (1) is positive (b > 0), enabling the saturation of the emerging patterns.

In the absence of nonlinear advection, that is, for small values of λ, the unconstrained system forms a square vortex lattice with “antiferromagnetic” order33,35, i.e., neighboring vortices rotate in opposite directions to reduce the hydrodynamic friction. The periodicity of this vortex lattice, i.e., the distance between the centers of two vortices of the same sense of rotation, is given by Λc = 2π/kc. We will refer to the wavelength Λc as intrinsic length scale of the bacterial suspension. In the unconstrained case, there is no direct correspondence between this length scale and experimentally observable quantities. In this work, we set Λc = 105 μm, which corresponds to the periodicity of the vortex patterns in the square pillar arrangement with an optimal lattice constant L ≈ 75 μm observed in ref. 19. This approach is based on the assumption that the highest stability of the emerging structures is reached when the geometry imposed by the pillars fits the intrinsic length scale of the suspension.

For larger values of λ, the system exhibits a dynamical state that has been denoted as mesoscale turbulence25,27,31,32,34,35. Due to the presence of an intrinsic length scale (which is absent in other continuum models such as the Toner–Tu equation38), Eq. (1) represents a convenient model to investigate the emergence of vortex patterns under geometrical constraints such as pillars. In order to realistically implement these constraints, we first examine the flow field around a single pillar to find appropriate boundary conditions for the effective continuum model.

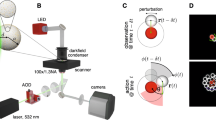

Flow field around a single pillar

We experimentally investigate the flow field around a single pillar in an otherwise unconstrained bacterial suspension. The corresponding setup consists of B. subtilis swimming around the bottom surface of a pendant drop. The drop is pierced by a vertical pillar with a diameter in the micron range, see Fig. 1a for a schematic representation and Supplementary Fig. 1 for microscopic snapshots. The velocity field v(x, t) of bacterial motion is obtained via particle image velocimetry (PIV). Note that this velocity field is not equivalent to the local orientation of the bacteria. Rather, it incorporates both the relative swimming speed of the cells and the advection by the solvent flow. Details on bacteria preparation, pillar manufacturing, and the experimental procedure can be found in the Methods section.

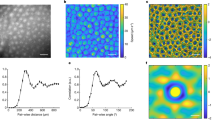

a Schematics of the experimental setup (top view) consisting of B. subtilis in the presence of a single pillar. b Experimental results for the time-averaged absolute velocity and vorticity vs the distance from the center of a (small) circular pillar of diameter l = 20 μm, obtained by calculating the mean value in a time window of 46.5 s and averaging over all orientations. The dashed lines indicate the location of the pillar surface. c Probability of the occurrence of certain topological charges located in the center of a single pillar obtained from a time series of the instantaneous charge. Numerical results are obtained by solving Eq. (7) with parameters a = 0.5, b = 1.6, λ = 9, γv = 40, γω = 4 and Λc = 105 μm. Experimental results were measured for two independent pillars. The error bars represent the standard deviations. Inset: sketch of the flow field around a defect of charge c = −1 and c = +1, respectively. d Experimental snapshots superimposed with the velocity field displaying topological charges c = +1, c = 0, c = −1 and c = −2. The pillar diameter is l = 20 μm except for the snapshot with c = −2 where it is l = 30 μm. Topological charges are calculated by using the cyan contours 15 μm away from the surface of the pillars. Scale bar: 20 μm. e–g Solutions of the linearized Eq. (1) in terms of Bessel functions of order n = 2 (e), n = 3 (f) and n = 4 (g).

We first analyze the average flow field in the vicinity of the pillar. To this end, we take the angle (i.e., spatial) average of the local flow field yielding the absolute values of the mean velocity v and vertical vorticity ω = (∇ × v)z as a function of the distance to the pillar center over a time window of 46.5 s. As a highly non-trivial effect, we observe that not only the velocity vanishes close to the pillar, but also the vorticity. This feature is shown in Fig. 1b, where the absolute velocity and vorticity are plotted as functions of the distance from a pillar. The pillar diameter20 is small compared to the pattern wavelength in the unconstrained suspension Λc = 105 μm (see Supplementary Note 1). As we show below, the pillar size is an important parameter. While the vanishing velocity v on a surface of the pillar is expected (no-slip boundary condition), the vanishing vorticity is surprising. Moreover, individual bacteria or other active swimmers tend to circle around a pillar due to hydrodynamic attraction39,40.

We proceed by considering the topological defects located at the pillars’ positions. These are singularities in the time-resolved bacterial velocity field v, which can be characterized by so-called topological charges c centered in the pillar. This approach allows to characterize the flow field surrounding the pillars on a structural level. The value of c is obtained from the number of clockwise revolutions of the velocity field’s orientation angle when encircling the obstacle in a clockwise direction. Since v has polar symmetry, the topological charges are integers. In particular, a charge c = 1 describes a vortex center, while negative charges (saddle points) correspond to defects located in the gap between adjacent vortices. Thus, c = −1 represents a defect surrounded by four vortices, c = −2 for six surrounding vortices, and c = −3 for eight surrounding vortices, etc. An illustration of the cases c = 1 and c = −1 is given in Fig. 1c (inset).

The experimental velocity field strongly fluctuates, and the instant topological charge is a time-dependent quantity (see Supplementary Fig. 2). We calculate c at each instant of time and then determine the probability distribution P(c). For the calculation of the topological charge, we use a contour around the pillar with a radius that is 15 μm larger than that of the pillar itself, avoiding the unreliability of the PIV measurements close to the walls (see Supplementary Methods for more details on the calculations of the charges). Figure 1d shows experimental snapshots superimposed with the velocity field for instances in time where the charges are c = +1, c = 0, c = −1, and c = −2 (see also Supplementary Movies 1–4 for the dynamics of bacterial motion around pillars of different diameter and Supplementary Movie 5 for an example of the dynamics of the topological charge). Analyzing the statistics of the charge, we find that P(c) strongly depends on the pillar size, see filled circles in Fig. 1c, where the probabilities for different values of c are plotted vs the pillar diameter l. For all diameters considered, the highest probability occurs at c = −1, i.e., the pillar is surrounded by four vortices. This feature explains the robustness of the square antiferromagnetic vortex lattice19. We also observe that increasing the pillar diameter increases the probability for more negative charges, c ≤ −2, while the charges c = 1 and c = 0 become even more unlikely. These experimental observations motivate the choice of boundary conditions we use to implement the pillars in our continuum description.

Boundary conditions on a pillar

Standard boundary conditions applied routinely when solving the Navier–Stokes equation (e.g., no-slip41), are not sufficient here because Eq. (1) contains gradient terms up to fourth order demanding a higher number of constraints. We propose two boundary conditions, which comply with the experimental observations for the averaged flow field around a single pillar, see Fig. 1b, and yield consistent collective behavior. In addition to the standard no-slip conditions, we require vanishing vorticity on the pillar:

We give further motivation for these boundary conditions in the Supplementary Note 2, based on recent experimental observations of complex flows in the boundary layers of bacterial suspensions near walls13,21,42.

Considering the linearized version of Eq. (1) in polar coordinates (r, φ) (with the conditions (2) applied in the origin) already yields quantitative insight into the effect of a single pillar. To this end, we linearize Eq. (1) around the homogeneous state v = 0 and consider only the stationary case. This yields in terms of the vorticity

In polar coordinates, the solution of Eq. (3) can be represented in terms of Bessel functions of the first kind, see Supplementary Note 3 for more details,

The boundary conditions (2) for an infinitesimally small pillar located at the origin correspond to ω|r=0 = 0 and v|r=0 = 0, respectively. Condition ω|r=0 = 0 implies that A0 = 0. Using the relation between vorticity ω and stream function Ψ, ∇2Ψ = −ω, we also derive from v|r=0 that A1 = 0. As a consequence, Eq. (4) must not contain terms with n = 0 or n = 1, and Bessel functions of different kinds are not allowed. The resulting lowest-order solution, n = 2, corresponds to four vortices surrounding a pillar, see Fig. 1e, and negative topological charge c = −1. If the pillar diameter l is not infinitesimally small, Bessel functions (4) with n > 2 may dominate the behavior for r > l. It is intuitively clear that increasing the pillar size will lead to higher cylindrical harmonics (more rigorous arguments are presented in Supplementary Note 3), which corresponds, in turn, to an increasing number of surrounding vortices. In Fig. 1e–g, the analytically obtained solutions are shown for n = 2, n = 3 and n = 4, respectively.

For quantitative predictions of the flow field, we have to resort to the numerical solution of Eq. (1). We apply a pseudo-spectral method and implement the boundary conditions (2) by local damping of the velocity v and vorticity ω (see Methods). The advantage of this approach is that the magnitude of the boundary effect can be controlled, which is crucial to reproduce the experimentally obtained topological charge distribution. In order to compare our theoretical results with the experiment, we numerically solve for the velocity field surrounding a single pillar in an otherwise unconstrained system and, analogously to the experiment, determine the distribution of topological charges, P(c), from the time series. Adjusting the damping strength and the coefficients in Eq. (1) appropriately we find very good agreement, see Fig. 1c. The parameters used here and in the rest of this work are a = 0.5, b = 1.6 and λ = 9. The size dependence of the topological charge of a single pillar opens up the intriguing possibility to design vortex patterns of different symmetries, including exotic ones not present in the unconstrained system.

Stabilization of symmetric vortex lattices

The insights into the structure of the flow field preferred by a single pillar can now be used to design various large-scale patterns by arranging several pillars of appropriate size. We investigate a square lattice of 9 × 9 pillars and a hexagonal lattice consisting of 48 pillars embedded in an otherwise unconstrained suspension, see Fig. 2a, b, respectively. To characterize the emergent order of the vortex patterns, we consider the gaps as regions of interest (ROI), as indicated in Fig. 2a, b, where one of the ROIs is marked by a black rectangle (square lattice) or circle (hexagonal lattice). Analogous to refs. 14,19, we define a spin variable Si as normalized velocity circulation for every ROI (see Supplementary Methods). From Si, we calculate the adjacent spin correlation χ:

a, b Snapshots of the flow field in a the square and b the hexagonal pillar arrays obtained by solution of Eq. (7). The lattices formed by the pillars (black circles) have lattice constants \(L = {\mathrm{\Lambda }}_{\mathrm{c}}/\sqrt 2 \approx 74\) μm and L = Λc ≈ 105 μm, respectively. One of the regions of interest (ROIs) used to analyze the emerging patterns is indicated by a black square and a black circle, respectively. Time-averaged adjacent spin correlation 〈χ〉t as a function of the lattice constant L obtained c by solving Eq. (7) and from experiments19 in the square lattice (error bars show the standard deviation among ROIs and are cut off below −1; the origin of large error bars due to distorted pillars is discussed in ref. 19), and d by solving Eq. (7) in the hexagonal lattice. The remaining parameters are a = 0.5, b = 1.6, λ = 9, γω = 4, γv = 40 and Λc = 105 μm. The pillar size is set to l = 14 μm for the square lattice and l = 53 μm for the hexagonal lattice.

where 〈i, j〉 denote pairs of neighboring ROIs (four neighbors in the square lattice, three in the hexagonal lattice case). The value χ = −1 (+1) corresponds to the perfect antiferromagnetic (ferromagnetic) order. The choice of the pillar diameter is motivated by the results for a single pillar (see Fig. 1c): For the square lattice, we expect every pillar to be surrounded by four vortices. Therefore, we need a quite small pillar diameter, corresponding to a preference for the charge c = −1. We set l = 14 μm to be able to compare to the experimental results presented in ref. 19, where this size is used. However, Fig. 1c suggests that slightly larger pillar diameters are even more suitable. In fact, we find that a diameter of l = 30 μm is more effective in stabilizing a stationary pattern in the square pillar lattice, see Supplementary Fig. 3. In the hexagonal lattice, the number of surrounding vortices is six. Therefore, we use pillars with a larger diameter yielding a higher probability for more negative charges (c ≤ −2). Trying out different pillar sizes, we find the highest stability for a diameter of l = 53 μm.

The stability of the resulting patterns and the corresponding values of χ crucially depend on the interplay between intrinsic length scale of the (unconstrained) bacterial suspension, Λc, and the lattice constant L of the pillar lattice (defined as the smallest distance between pillars, see Fig. 2a, b). Figure 2c, d shows numerical results for the time-averaged adjacent spin correlation over L for square and hexagonal lattices. For comparison, the results from the experiments on square lattices19 are included. Both lattice types lead to strong antiferromagnetic ordering, provided L is in an optimal range, which appears to be L ≈ 60–80 μm for the square and L ≈ 100–110 μm for the hexagonal lattices. In addition to the emergence of strong spatial correlations, we also observe a dramatic increase of temporal correlations, see Supplementary Fig. 4 for details and Supplementary Movies 6 and 7, which show the dynamics of the emerging patterns.

To understand the origin of the stabilization regions, we take a closer look at the geometric structure of the vortex patterns, see Fig. 3a, b, which show a schematic representation of the periodic lattices. The emerging vortex patterns after stabilization can be represented in terms of M Fourier modes characterized by wavevectors kj, i.e.,

Comparison of symmetries present in the stabilized vortex patterns for different pillar configurations: a square, b hexagonal, and c Kagome lattices of pillars (denoted by black circles). The arrows in the gray circles show the directions of the wavevectors when representing the emerging vortex structures in terms of Fourier modes. The unit cell of the spatially periodic vortex structure is marked by the light green color. Axes of reflection are denoted by the dashed gray lines. Centers of rotation within the unit cell are marked by yellow polygons: diamond shapes for a rotational symmetry of order two (180°), triangles for a rotational symmetry of order three (120°), squares for a rotational symmetry of order four (90°), and hexagons for a rotational symmetry of order six (60°). The absence of mirror symmetries in the vortex pattern stabilized by the Kagome-like pillar lattice implies the chirality of the structure.

where c.c. denotes the complex conjugate and \(\tilde \omega _j\) the amplitude of mode j. In particular, the square vortex lattice can be described, to lowest order, by a superposition of two modes with perpendicular wavevectors k1, k2, and the triangular vortex lattice constitutes a superposition of three modes with an angle of 60° between wavevectors (see Supplementary Discussion for explicit mathematical representations). In this sense, the geometry of the pillar arrangement imposes a certain symmetry and length scale (related to the magnitude of kj) onto the emerging patterns. In Fig. 3, the respective configuration of the modes is shown by the arrows in the gray circles. Geometrical arguments give the dependence of the largest wavelength of the vortex pattern on the lattice constant in the respective pillar arrangement. We can connect this wavelength to the linear stability analysis for the unconstrained case (see Supplementary Note 1). One would expect stable patterns to occur once the linear growth rate associated with the wavelength becomes positive. This yields \(L_{{\mathrm{sq}}}^{{\mathrm{crit}}} \approx 56.8\) μm and \(L_{{\mathrm{hex}}}^{{\mathrm{crit}}} \approx 92.8\) μm for the critical lattice constants of the square and the hexagonal pillar arrays (see Supplementary Discussion for the details of the calculation), which agrees very well with the numerical results shown in Fig. 2. The discontinuity of the adjacent spin correlation observed at the critical lattice constant is due to the finite size of the pillars. The pattern formation is strongly damped for smaller lattice constants and, once the lattice constant is large enough, the growth rate of the imposed wavelength is already quite large, which results in very stable ordering. As the pillars in the hexagonal arrangement are much larger, this effect is more pronounced.

In contrast, the right border of the stabilization region cannot be explained by linear stability. Increasing L beyond a threshold value (Lsq ≈ 80 μm and Lhex ≈ 110 μm for the square and the hexagonal lattice, respectively), the nonlinear advection term takes effect which leads to the onset of mesoscale turbulence within the lattice, preventing any kind of stable stationary order. This transition from regular to turbulent patterns by increasing the available space has also been found in the context of active nematics in channel geometries43,44 and circular flow chambers45,46.

Given the patterns in Fig. 2, it is important to recall that Eq. (1) yields a square lattice in an unconstrained system26,33,35, but only for advection strengths λ smaller than the value used for the results in Fig. 2 (below the onset of mesoscale turbulence). In this sense, the square pillar arrangement suppresses the nonlinear instability caused by the advection term and leads to the stabilization of the underlying square pattern. This also explains why the range of optimal lattice constants is significantly smaller for the hexagonal lattice compared to the square one: In the absence of confinement and advection, a square pattern would emerge, rather than a triangular structure.

Finally, it is useful to consider the stabilized vortex patterns in terms of symmetry groups. Both structures can be viewed as bipartite (two-colored) tilings of the plane (with pillars occupying the vertices of the tiling). Indeed, in a stable pattern, neighboring vortices must have an opposite sense of rotation to reduce the hydrodynamic friction. Thus, neighboring regions are not allowed to have the same color. In the case of a square pillar lattice (Fig. 3a), the stabilized pattern is a periodic vortex structure consisting of two square sublattices. It belongs to the wallpaper group p4g47. In the second case (Fig. 3b), the emerging triangular structure belongs to the wallpaper group p3m147. Both of these patterns have one important feature: They possess axes of symmetry, denoted by the dashed gray lines in Fig. 3, which means that they are achiral. Moreover, the total vorticity in each unit cell is zero.

Kagome lattice and non-zero circulation

The antiferromagnetic order condition of neighboring regions restricts the possibilities (similar to the case of antiferromagnetic Ising spin lattices), e.g., both a truncated square tiling and a honeycomb lattice are not suited19. However, by choosing a suitable pillar arrangement we can force the bacterial suspension to form a chiral pattern that does not possess mirror symmetries and displays a non-zero net rotational flow.

An intriguing example of a chiral pattern emerges when we place the pillars on the sites of a Kagome lattice as shown in Figs. 3c and 4a. The stabilized structure consists of a hexagonal lattice of large vortices with one sense of rotation and a honeycomb lattice of small vortices of opposite sense of rotation, corresponding to the wallpaper group p647. This vortex pattern, which does not possess an axis of symmetry, is a consequence of spontaneous mirror symmetry breaking, as both the patterns in the unconstrained system (for values of λ below the onset to turbulence) as well as the Kagome lattice of pillars do possess mirror symmetries. We stress that this structure differs from that of antiferromagnetic (Ising or Heisenberg) spin systems on Kagome lattices, which are typically characterized by some degree of frustration48,49. The difference is that the vortices fill the gaps between pillar sites, rather than being placed on them, thereby avoiding frustration. To ensure that every pillar in this pattern is surrounded by four vortices, we set the pillar diameter to an appropriate value, i.e., l = 21 μm, corresponding to a strong preference for the charge c = −1, see Fig. 1c. The vortex structure possesses a two-fold degeneracy because it is equally stable when the sense of rotation of all vortices is reversed.

a Snapshot of the flow field obtained by solution of Eq. (7) with lattice constant L = 0.65 Λc ≈ 68 μm. Pillars are denoted by black circles. The circulation is calculated along the enclosing loop indicated by the black hexagon, which has a side length that equals four times the lattice constant L. b Absolute value of the time-averaged circulation |〈Γ〉| over lattice constant L. The averaging time window is Δt = 1000 (in simulation time units), which is smaller than the average time it takes the circulation to flip at the transition Lcrit ≈ 52.5 μm, and much larger than the time scale of the fluctuations outside of the range of optimal lattice constants (indicated by the green area). c Time-resolved spatially averaged vorticity of the center hexagonal gap for different values of the lattice constant. For L below the transition value Lcrit ≈ 52.5 μm, the vorticity fluctuates around zero, whereas above the transition we observe a persistent rotation leading to the net circulation of the whole arrangement. For comparison, the values of the lattice constants in (c) are indicated in (b) by colored lines. Numerical results are obtained by solution of Eq. (7) The remaining parameters are a = 0.5, b = 1.6, λ = 9, γω = 4, γv = 40, Λc = 105 μm and pillar size l =0.2 Λc = 21 μm.

The two different lengths characterizing the Kagome pillar lattice together with the finite size of the pillars yield a striking consequence: the emergence of a net rotational flow around the arrangement of pillars. This flow is quantified by the circulation Γ defined as the integral of the vorticity in the area A, enclosed in the loop denoted by the large black hexagon in Fig. 4a, \({\mathrm{\Gamma }} = \mathop {\oint }\nolimits_{\partial A} {\mathbf{v}} \cdot d{\mathbf{s}} = \mathop {\iint}\nolimits_A {\omega dA}\). Here ds denotes the infinitesimal line element on the closed loop ∂A. The absolute value of the time-averaged circulation is plotted in Fig. 4b over the lattice constant (given by the smallest distance between pillars, see Fig. 4a). One observes non-zero values of Γ in the range L ≈ 55–85 μm. To understand the origin of this effect, we take a closer look at the Kagome lattice geometry: As before, the lattice geometry imposes directions and length scale in terms of Fourier modes of the emerging patterns. Similar to the square and the hexagonal lattice, we can connect the emerging patterns to the linear growth rate obtained for the unconstrained system. When the linear growth rate associated with the respective wavelength changes sign, patterns start to grow. This yields \(L_{{\mathrm{Kag}}}^{{\mathrm{crit}}} \approx 46.4\) μm for the critical wavelength (see Supplementary Discussion for details of the calculation), which is comparable to the onset of persistent circulation, compare Fig. 4b, where we find numerically \(L_{{\mathrm{Kag}}}^{{\mathrm{crit}}} \approx 52.5\) μm. To further illustrate the nature of the transition, we plot a typical time series of the spatially averaged vorticity in the central hexagonal gap in Fig. 4c for different lattice constants. For values below \(L_{{\mathrm{Kag}}}^{{\mathrm{crit}}}\) the average vorticity fluctuates around zero, demonstrating the achirality of the system. Increasing the lattice constant beyond \(L_{{\mathrm{Kag}}}^{{\mathrm{crit}}}\), the symmetry is broken resulting in persistent non-zero vorticity (see also Supplementary Fig. 5 and Supplementary Movie 8), where the direction of rotation determines the sign of the overall circulation. For intermediate lattice constants, the system occasionally flips this sign, as can be seen in Fig. 4c. We set the time window for the averaging of the circulation shown in Fig. 4b to Δt = 1000 (in simulation time units), such that the short-scale fluctuations are averaged out, but the persistent motion is captured. Note that the size of the pillars plays an important role, as the smaller vortices (being located in the small triangular gaps) are affected stronger than the larger vortices (being located in the much larger hexagonal areas). As a consequence, they experience stronger damping, whereas the larger vortices can develop fully, determining the direction of the net rotational flow. When increasing the lattice constant beyond the maximum, the pillars are too far apart for the stabilization and mesoscale turbulence sets in, preventing the formation of ordered states. We stress that the effect of inducing such large-scale circulation is, in principle, present for arbitrarily large pillar arrangements.

Discussion

In this study, we show how periodic arrays of small pillars impose minimal geometrical constraints that lead to the stabilization of complex vortex lattices in an originally turbulent bacterial suspension. The emerging vortex patterns are crucially determined by only a few ingredients. First, the size of a pillar controls the number of vortices around that pillar, enabling a different number of “nearest neighbors” in the language of a spin lattice. Second, the ratio of the pillar lattice constant to the intrinsic length scale of the unconstrained suspension determines the stability and degree of antiferromagnetic order. The third major ingredient is the geometry of the unit cell of the pillar array. We demonstrate how a Kagome lattice with two length scales stabilizes a chiral vortex pattern (no mirror symmetries) exhibiting a net rotational flow. Kagome active materials have been suggested in ref. 50. However, in ref. 50, the authors focus on the stabilization of topologically protected sound modes51, in analogy to the “edge modes” in topological insulators. Realizing topological edge modes in the context of active materials is an ongoing research topic52,53, usually approached by investigating systems described by the Toner–Tu equation38. The system considered here is fundamentally different. First, the Toner–Tu equation lacks the characteristic length scale, a hallmark feature of bacterial turbulence24,27,54 which is essential for the stabilization of regular vortex patterns. Without length scale selection, small pillars with rotational symmetry are not sufficient to stabilize a vortex lattice and stronger confinement is needed, e.g., circular walls52, curved surfaces53, or pillars with more complex symmetries50. Second, in contrast to the anomalous properties of sound propagation51,52,53, the observed effect here is not topological in origin. Rather, the induced circulation follows from a combination of mirror symmetry breaking and length scale selection.

Most of our results have been obtained by numerical integration. We have introduced novel boundary conditions [Eq. (2)] which are motivated by two key properties of the pillars: local reduction of velocity and vorticity. Given the consistency with experimental results, our boundary conditions may be used in future works to describe the interaction between active fluids and boundaries on a coarse-grained, order parameter level.

Our results have demonstrated the effectiveness of small geometrical constraints, i.e., pillars, to transform the chaotic motion of bacterial suspensions into ordered vortex arrays. They provide an insight into the key mechanisms and design rules for pillar lattices suitable to stabilize vortex patterns with different symmetries. The experimental approach developed in ref. 19 (microprinting by direct laser lithography) may be used to test our theoretical predictions for other lattice types. The intriguing properties of the bacterial vortex pattern emerging in the Kagome lattice may be useful in future applications, e.g., for the transport of passive particles via advection or the extraction of useful work at the microscale. When using microscopic gears to extract work55, a pre-defined chirality is required for the gear to spin. Similar to ref. 56, this is not a prerequisite in our setup as the mirror symmetry is spontaneously broken by the emerging vortex pattern, opening up new possibilities for the design of active microfluidic systems.

Methods

Sample preparation

The pillars were 3D printed on a glass slide from a photopolymer resist (IP-Dip) by direct laser lithography, Photonic Professional GT system, Nanoscribe GmbH. A variety of pillar sizes and shapes were printed, the most common were 150 μm tall, and the width changed in the range from 14 to 90 μm. Pillars with circular and square cross-sections were studied. Additional details on the printing procedure can be found in ref. 19. The suspensions of swimming bacteria B. subtilis (strain 1085) were prepared according to the protocol described in refs. 19,24. The bacteria were inoculated on an LB agar plate (Sigma-Aldrich) and incubated in liquid growth medium Terrific Broth (TB) at 30°C overnight. After the growth, the bacteria were washed, concentrated by centrifugation, and transferred in fresh TB medium. For typical experimental concentrations of the order of 1010 cm−3, the bacteria exhibit collective swimming with a typical speed ≈50–60 μm s−1 24.

Experimental procedure

A droplet of a concentrated suspension was deposited by a pipette on a glass slide with the printed microscopic pillars. The thickness of the droplet was slightly smaller than the pillar’s height to ensure that the pillars pierce the droplet. To prevent evaporation, the droplet was enclosed by a coverslip separated from the glass slide by a spacer, see ref. 19 for details. The sample was flipped. The experimental images were acquired by an Olympus IX71 inverted microscope and a high-resolution (5120 × 3840) RGB color camera HS20000C at a magnification of ×10 to ×20 and at 43–60 frames per second depending on the experiments.

Image processing

The bacterial velocity field v(x, t) was calculated by custom particle image velocimetry (PIV) MATLAB scripts developed in ref. 19. In the case of estimating the boundary conditions, for example, after extracting only the red pixels, which have the best contrast among all the three colors, the velocity field was estimated by applying particle image velocimetry (PIV) on the red pixel images with the 32 × 32 pixels (10.2 μm × 10.2 μm) PIV subwindows separated by 8 pixels (2.6 μm) with 75% overlap, the spatial resolution being smaller than any characteristic scales of the observed collective motion. To avoid the deceleration of bacterial activities, the first 2000 frames (46.5 s) of the obtained images were used for the analysis. Different parameters were used for the estimation of topological charge distributions, see Supplementary Methods for details.

Numerical methods

Our numerical analysis for bacterial turbulence in the presence of obstacles is based on Eq. (1), a recent Swift–Hohenberg-like model for the effective bacterial velocity vector v25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35. To simplify the analysis, we rewrite Eq. (1) in terms of the vorticity ω = (∇ × v)z,

The two additional terms in Eq. (7) incorporate the local damping of velocity and vorticity with the damping coefficients γv and γω, respectively. The kernel (or “mask”) K(r) contains all the information about the shape, geometry, and configuration of pillars by specifying the damping at position r. Here, we choose the following generalized Gaussian function:

where ri is the location of pillar i. The pillar diameter l is defined by the distance to the center where the damping is reduced to 0.01% of γv and γω, respectively. The concrete form of the Kernel function (8) is somewhat arbitrary, e.g., another possibility would be to construct the potential using the tanh-function. As the damping coefficients are adjustable parameters, chosen to reproduce the experimental results, the detailed form of the Kernel function is not of crucial importance. To check this point, we performed numerical calculations using different Kernel functions and did not observe any qualitative difference in the structure of the surrounding flow field. For all numerical results shown in this work, the damping coefficients are set to γv = 40 and γω = 4, yielding very good agreement with the experiment. Equation (7) is solved with a pseudospectral method. Using operator splitting, the linear part is solved exactly and the nonlinear part is integrated in time applying Euler’s method. The initial velocity field is set to zero with a small perturbation added at every grid point. Before we start the analysis of the emerging patterns, we let the system evolve for 1000 time units, which is at least an order of magnitude larger than the time it takes full vortex structures to form from the quiescent initial state. If not otherwise stated, the time window for temporal averages is, at least, Δt = 2000.

Data availability

The data in support of the reported findings are available from the corresponding author upon a reasonable request.

Code availability

The computer codes used for the numerical calculations are available from the corresponding author upon a reasonable request.

References

Sokolov, A., Aranson, I. S., Kessler, J. O. & Goldstein, R. E. Concentration dependence of the collective dynamics of swimming bacteria. Phys. Rev. Lett. 98, 158102 (2007).

Sanchez, T., Chen, D. T., DeCamp, S. J., Heymann, M. & Dogic, Z. Spontaneous motion in hierarchically assembled active matter. Nature 491, 431 (2012).

Suzuki, R., Weber, C. A., Frey, E. & Bausch, A. R. Polar pattern formation in driven filament systems requires non-binary particle collisions. Nat. Phys. 11, 839 (2015).

Saw, T. B. et al. Topological defects in epithelia govern cell death and extrusion. Nature 544, 212 (2017).

Nishiguchi, D., Nagai, K. H., Chaté, H. & Sano, M. Long-range nematic order and anomalous fluctuations in suspensions of swimming filamentous bacteria. Phys. Rev. E 95, 020601 (2017).

Deseigne, J., Dauchot, O. & Chaté, H. Collective motion of vibrated polar disks. Phys. Rev. Lett. 105, 098001 (2010).

Aranson, I. S., Volfson, D. & Tsimring, L. S. Swirling motion in a system of vibrated elongated particles. Phys. Rev. E 75, 051301 (2007).

Nishiguchi, D. & Sano, M. Mesoscopic turbulence and local order in Janus particles self-propelling under an ac electric field. Phys. Rev. E 92, 052309 (2015).

Nishiguchi, D., Iwasawa, J., Jiang, H.-R. & Sano, M. Flagellar dynamics of chains of active janus particles fueled by an ac electric field. N. J. Phys. 20, 015002 (2018).

Bricard, A., Caussin, J.-B., Desreumaux, N., Dauchot, O. & Bartolo, D. Emergence of macroscopic directed motion in populations of motile colloids. Nature 503, 95 (2013).

Kokot, G. et al. Active turbulence in a gas of self-assembled spinners. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 114, 12870–12875 (2017).

Gompper, G. et al. The 2020 motile active matter roadmap. J. Phys.: Condens. Matter 32, 193001 (2020).

Wioland, H., Woodhouse, F. G., Dunkel, J., Kessler, J. O. & Goldstein, R. E. Confinement stabilizes a bacterial suspension into a spiral vortex. Phys. Rev. Lett. 110, 268102 (2013).

Wioland, H., Woodhouse, F. G., Dunkel, J. & Goldstein, R. E. Ferromagnetic and antiferromagnetic order in bacterial vortex lattices. Nat. Phys. 12, 341 (2016).

Morin, A., Desreumaux, N., Caussin, J.-B. & Bartolo, D. Distortion and destruction of colloidal flocks in disordered environments. Nat. Phys. 13, 63 (2017).

Sokolov, A. & Aranson, I. S. Rapid expulsion of microswimmers by a vortical flow. Nat. Commun. 7, 11114 (2016).

Słomka, J. & Dunkel, J. Geometry-dependent viscosity reduction in sheared active fluids. Phys. Rev. Fluids 2, 043102 (2017).

Sokolov, A., Rubio, L. D., Brady, J. F. & Aranson, I. S. Instability of expanding bacterial droplets. Nat. Commun. 9, 1322 (2018).

Nishiguchi, D., Aranson, I. S., Snezhko, A. & Sokolov, A. Engineering bacterial vortex lattice via direct laser lithography. Nat. Commun. 9, 4486 (2018).

Turiv, T. et al. Polar jets of swimming bacteria condensed by a patterned liquid crystal. Nat. Phys. 16, 481–487 (2020).

Lushi, E., Wioland, H. & Goldstein, R. E. Fluid flows created by swimming bacteria drive self-organization in confined suspensions. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 111, 9733–9738 (2014).

Beppu, K. et al. Geometry-driven collective ordering of bacterial vortices. Soft Matter 13, 5038–5043 (2017).

Dombrowski, C., Cisneros, L., Chatkaew, S., Goldstein, R. E. & Kessler, J. O. Self-concentration and large-scale coherence in bacterial dynamics. Phys. Rev. Lett. 93, 098103 (2004).

Sokolov, A. & Aranson, I. S. Physical properties of collective motion in suspensions of bacteria. Phys. Rev. Lett. 109, 248109 (2012).

Wensink, H. H. et al. Meso-scale turbulence in living fluids. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 109, 14308–14313 (2012).

Dunkel, J., Heidenreich, S., Bär, M. & Goldstein, R. E. Minimal continuum theories of structure formation in dense active fluids. N. J. Phys. 15, 045016 (2013).

Dunkel, J. et al. Fluid dynamics of bacterial turbulence. Phys. Rev. Lett. 110, 228102 (2013).

Słomka, J. & Dunkel, J. Generalized Navier-Stokes equations for active suspensions. Eur. Phys. J. Spec. Top. 224, 1349–1358 (2015).

Oza, A. U., Heidenreich, S. & Dunkel, J. Generalized Swift-Hohenberg models for dense active suspensions. Eur. Phys. J. E 39, 97 (2016).

Bratanov, V., Jenko, F. & Frey, E. New class of turbulence in active fluids. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 112, 15048–15053 (2015).

Heidenreich, S., Dunkel, J., Klapp, S. H. L. & Bär, M. Hydrodynamic length-scale selection in microswimmer suspensions. Phys. Rev. E 94, 020601 (2016).

Reinken, H., Klapp, S. H., Bär, M. & Heidenreich, S. Derivation of a hydrodynamic theory for mesoscale dynamics in microswimmer suspensions. Phys. Rev. E 97, 022613 (2018).

Reinken, H., Heidenreich, S., Baer, M. & Klapp, S. Anisotropic mesoscale turbulence and pattern formation in microswimmer suspensions induced by orienting external fields. N. J. Phys. 21, 013037 (2019).

James, M. & Wilczek, M. Vortex dynamics and lagrangian statistics in a model for active turbulence. Eur. Phys. J. E 41, 21 (2018).

James, M., Bos, W. J. & Wilczek, M. Turbulence and turbulent pattern formation in a minimal model for active fluids. Phys. Rev. Fluids 3, 061101 (2018).

Toner, J., Tu, Y. & Ramaswamy, S. Hydrodynamics and phases of flocks. Ann. Phys. 318, 170–244 (2005).

Aranson, I., Gorshkov, K., Lomov, A. & Rabinovich, M. Stable particle-like solutions of multidimensional nonlinear fields. Physica D 43, 435–453 (1990).

Toner, J. & Tu, Y. Flocks, herds, and schools: a quantitative theory of flocking. Phys. Rev. E 58, 4828 (1998).

Berke, A. P., Turner, L., Berg, H. C. & Lauga, E. Hydrodynamic attraction of swimming microorganisms by surfaces. Phys. Rev. Lett. 101, 038102 (2008).

Takagi, D., Palacci, J., Braunschweig, A. B., Shelley, M. J. & Zhang, J. Hydrodynamic capture of microswimmers into sphere-bound orbits. Soft Matter 10, 1784–1789 (2014).

Pozrikidis, C. Introduction to Theoretical and Computational Fluid Dynamics. (Oxford University Press: New York, 2011.

Wioland, H., Lushi, E. & Goldstein, R. E. Directed collective motion of bacteria under channel confinement. N. J. Phys. 18, 075002 (2016).

Shendruk, T. N., Doostmohammadi, A., Thijssen, K. & Yeomans, J. M. Dancing disclinations in confined active nematics. Soft Matter 13, 3853–3862 (2017).

Chandragiri, S., Doostmohammadi, A., Yeomans, J. M. & Thampi, S. P. Active transport in a channel: stabilisation by flow or thermodynamics. Soft Matter 15, 1597–1604 (2019).

Gao, T., Betterton, M. D., Jhang, A.-S. & Shelley, M. J. Analytical structure, dynamics, and coarse graining of a kinetic model of an active fluid. Phys. Rev. Fluids 2, 093302 (2017).

Norton, M. M. et al. Insensitivity of active nematic liquid crystal dynamics to topological constraints. Phys. Rev. E 97, 012702 (2018).

Schattschneider, D. The plane symmetry groups: their recognition and notation. Am. Math. Mon. 85, 439–450 (1978).

Mekata, M. Kagome: the story of the basketweave lattice. Phys. Today 56, 12 (2003).

Zhou, Y., Kanoda, K. & Ng, T.-K. Quantum spin liquid states. Rev. Mod. Phys. 89, 025003 (2017).

Sone, K. & Ashida, Y. Anomalous topological active matter. Phys. Rev. Lett. 123, 205502 (2019).

Zhang, X., Xiao, M., Cheng, Y., Lu, M.-H. & Christensen, J. Topological sound. Commun. Phys. 1, 97 (2018).

Souslov, A., Van Zuiden, B. C., Bartolo, D. & Vitelli, V. Topological sound in active-liquid metamaterials. Nat. Phys. 13, 1091 (2017).

Shankar, S., Bowick, M. J. & Marchetti, M. C. Topological sound and flocking on curved surfaces. Phys. Rev. X 7, 031039 (2017).

Ilkanaiv, B., Kearns, D. B., Ariel, G. & Beer, A. Effect of cell aspect ratio on swarming bacteria. Phys. Rev. Lett. 118, 158002 (2017).

Sokolov, A., Apodaca, M. M., Grzybowski, B. A. & Aranson, I. S. Swimming bacteria power microscopic gears. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 107, 969–974 (2010).

Thampi, S. P., Doostmohammadi, A., Shendruk, T. N., Golestanian, R. & Yeomans, J. M. Active micromachines: microfluidics powered by mesoscale turbulence. Sci. Adv. 2, e1501854 (2016).

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Gil Ariel, Bernold Fiedler, Fernando Peruani, and Michael Wilczek for fruitful discussions. This work was funded by the Deutsche For-schungs-ge-mein-schaft (DFG, German Research Foundation)—Projektnummer 163436311—SFB 910. The research of I.S.A. was supported by the NSF PHY-1707900. S.H. and M.B. acknowledge financial support by DFG through the Middle-East program via combined grants (BA 1222/7-1 and HE 5995/3-1). D.N. was supported by JSPS KAKENHI Grant Numbers JP19K23422, JP19H05800 and JP20K14426. A.S. was supported by the U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Science, Basic Energy Sciences, Materials Sciences, and Engineering Division.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

I.S.A., S.H.L.K., and M.B. designed the research. H.R. designed and performed computational calculations. D.N. and A.S. performed experiments and analyzed the data. I.S.A. and S.H. contributed to analytical concepts. All authors wrote the paper and discussed the results.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Reinken, H., Nishiguchi, D., Heidenreich, S. et al. Organizing bacterial vortex lattices by periodic obstacle arrays. Commun Phys 3, 76 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s42005-020-0337-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s42005-020-0337-z

This article is cited by

-

Chiral active particles are sensitive reporters to environmental geometry

Nature Communications (2024)

-

Comparison of particle image velocimetry and the underlying agents dynamics in collectively moving self propelled particles

Scientific Reports (2023)

-

Emergence of synchronised rotations in dense active matter with disorder

Communications Physics (2023)

-

Self-mixing in microtubule-kinesin active fluid from nonuniform to uniform distribution of activity

Nature Communications (2022)

-

Collective migration reveals mechanical flexibility of malaria parasites

Nature Physics (2022)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.