Abstract

The Kibble–Zurek mechanism (KZM) describes the dynamics across a phase transition leading to the formation of topological defects, such as vortices in superfluids and domain walls in spin systems. Here, we experimentally probe the distribution of kink pairs in a one-dimensional quantum Ising chain driven across the paramagnet-ferromagnet quantum phase transition, using a single trapped ion as a quantum simulator in momentum space. The number of kink pairs after the transition follows a Poisson binomial distribution, in which all cumulants scale with a universal power law as a function of the quench time in which the transition is crossed. We experimentally verified this scaling for the first cumulants and report deviations due to noise-induced dephasing of the trapped ion. Our results establish that the universal character of the critical dynamics can be extended beyond KZM, which accounts for the mean kink number, to characterize the full probability distribution of topological defects.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The understanding of nonequilibrium quantum matter stands out as a fascinating open problem at the frontiers of physics. Few theoretical tools account for the behavior away from equilibrium in terms of equilibrium properties. One such paradigm is the so-called Kibble–Zurek mechanism (KZM) that accounts for the universal critical dynamics of a system driven across a phase transition. Pioneering insights on the KZM were conceived in a cosmological setting1 and applied to describe thermal continuous phase transitions2,3,4. The resulting KZM was later extended to quantum phase transitions5,6,7,8, see ref. 9 for a review. Its central prediction is that the average total number of topological defects 〈nT〉, formed when a system is driven through a critical point in a time scale τQ, is given by a universal power law \(\langle {n}^{{\rm{T}}}\rangle \sim {\tau }_{{\rm{Q}}}^{-\beta }\). The power-law exponent β = Dν∕(1 + zν) is fixed by the dimensionality of the system D and a combination of the equilibrium correlation length and dynamic critical exponents, denoted by ν and z, respectively. Essentially, the KZM is a statement about the breakdown of the adiabatic dynamics across a critical point. As such, it provides useful heuristics for the preparation of ground-state phases of matter in the laboratory, e.g., in quantum simulation and adiabatic quantum computation10. It has spurred a wide variety of experimental efforts in superfluid helium11,12,13, liquid crystals14,15, convective fluids16,17, superconducting rings18,19,20, trapped ions21,22,23, colloids24, and ultracold atoms25,26,27,28,29, to name some relevant examples. This activity has advanced our understanding of critical dynamics, e.g., by extending the KZM to inhomogeneous systems30,31. In the quantum domain, experimental progress has been more limited and led by the use of quantum simulators in a variety of platforms32,33,34.

Beyond the focus of the KZM, the full counting statistics encoded in the probability distribution can be expected to shed further light. The number distribution of topological defects has become available in recent experiments35. In addition, the distribution of kinks has recently been explored theoretically in the one-dimensional transverse-field quantum Ising model (TFQIM)36, a paradigmatic testbed of quantum phase transitions37. Indeed, it has been argued that the distribution of topological defects is generally determined by the scaling theory of phase transitions and thus exhibits signatures of universality beyond the KZM36.

We aim at validating this prediction experimentally using a single-trapped ion as a quantum simulator and probe the quantum critical dynamics of the TFQIM in momentum space. Specifically, we show that the measured distribution of kink pairs is Poisson binomial and that low-order cumulants scale as a universal power law with the quench time.

Results

Quantum critical dynamics

The TFQIM is described by the Hamiltonian

that we shall consider with periodic boundary conditions \({\hat{\sigma }}_{1}^{z}={\hat{\sigma }}_{N+1}^{z}\) and N even. Additionally, \({\hat{\sigma }}_{m}^{z}\) and \({\hat{\sigma }}_{m}^{x}\) are Pauli matrices at the site m and g plays the role of a (dimensionless) magnetic field that favors the alignment of the spins along the x-axis. This system exhibits a quantum phase transition between a paramagnetic phase (∣g∣ ≫ 1) and a doubly degenerated phase with ferromagnetic order (∣g∣ ≪ 1). There are two critical points at gc = ±1. We shall consider the nonadiabatic crossing of the critical point gc = −1 after initializing the system in the paramagnetic phase and ending in a ferromagnetic phase. Our quantum simulation approach relies on the equivalence of in the TFQIM in one spatial dimension and an ensemble of independent two-level systems. This result forms the basis of much of the progress on the study of quantum phase transitions and can be established via the Jordan–Wigner transformation38, Fourier transform, and Bogoliubov transformation39. We detail these steps in the Supplementary Note 1, where it is shown that the TFQIM Hamiltonian can be alternatively written in terms of independent modes as37,40

where \({\hat{\gamma }}_{k}\) are quasiparticle operators, with k labeling each mode and taking values \(k=\frac{\pi }{N}\left(2m-1\right)\) with \(m=-\frac{N}{2}+1,\ldots ,\frac{N}{2}\). The energy ϵk of the k-th mode is \({\epsilon }_{k}\left(g\right)=2J\sqrt{{\left(g-\cos k\right)}^{2}+{\sin }^{2}k}\). Other physical observables can as well be expressed in both the spin and momentum representations. We are interested in characterizing the number of kinks. As conservation of momentum dictates that kinks are formed in pairs, we focus on the kink-pair number operator \({\hat{\mathcal{N}}}\,\equiv \,\sum _{m = 1}^{N}\left({\hat{1}}-{\hat{\sigma }}_{m}^{z}{\hat{\sigma }}_{m+1}^{z}\right)/4\). The later can be equivalently written as \({\hat{\mathcal{N}}}=\sum_{k > 0}{\hat{\gamma }}_{k}^{\dagger }{\hat{\gamma }}_{k}\), where \({\hat{\gamma }}_{k}^{\dagger }{\hat{\gamma }}_{k}\) is a Fermion number operator, with eigenvalues {0, 1}. As different k-modes are decoupled, this representation paves the way to simulate the dynamics of the phase transition in the TFQIM in "momentum space”: the dynamics of each mode can be simulated with an ion-trap qubit, in which the expectation value of \({\hat{\gamma }}_{k}^{\dagger }{\hat{\gamma }}_{k}\) can be measured. To this end, we consider the quantum critical dynamics induced by a ramp of the magnetic field

in a time scale τQ that we shall refer to as the quench time. We further choose g(0) < −1 in the paramagnetic phase. In momentum space, driving the phase transition is equivalently described by an ensemble of Landau–Zener crossings. This observation proved key in establishing the validity of the KZM in the quantum domain7,32,33: the average number of kink pairs \(\langle \hat{{\mathcal{N}}}\rangle =\langle n\rangle\) after the quench scales as

in agreement with the universal power law \({\langle n\rangle }_{{\rm{KZM}}}\propto {\tau }_{{\rm{Q}}}^{-\frac{\nu }{1+z\nu }}\), with critical exponents ν = z = 1 and one spatial dimension (D = 1).

The full counting statistics of topological defects is encoded in the probability P(n) that a given number of kink pairs n is obtained as a measurement outcome of the observable \(\hat{{\mathcal{N}}}\). To explore the implications of the scaling theory of phase transitions, we focus on the characterization of the probability distribution P(n) of the kink-pair number in the final nonequilibrium state upon completion of the crossing of the critical point induced by Eq. (3). Exploiting the equivalence between the spin and momentum representation, the dynamics in each mode leads to two possible outcomes, corresponding to the mode being found in the excited state (e) or the ground state (g), with probabilities pe = pk and pg = 1 − pk, respectively. Thus, one can associate with each mode k > 0 a discrete random variable, with excitation probability \({p}_{k}=\langle {\hat{\gamma }}_{k}^{\dagger }{\hat{\gamma }}_{k}\rangle\). The excitation probability of each mode is that of Bernoulli type. As the kink-pair number n is associated with the number of modes excited, P(n) is a Poisson binomial distribution, with the characteristic function36

associated with the sum of N/2 independent Bernoulli variables. The mean and variance of P(n) are thus set by the respective sums of the mean and variance of the N/2 Bernoulli distributions characterizing each mode, 〈n〉 = ∑k>0pk and Var(n) = ∑k>0pk(1 − pk). The full distribution P(n) can be obtained via an inverse Fourier transform. The theoretical prediction of the kink distribution P(n) relies on knowledge of the excitation probabilities {pk}, which can be estimated using the Landau–Zener formula \({p}_{k}=\exp \left(-\frac{\pi }{\hslash }J{\tau }_{{\rm{Q}}}{k}^{2}\right)\)7 (details are given in Supplementary Note 2).

Experimental design

Experimentally, the excitation probabilities {pk} can be measured by probing the dynamics in each mode, that is simulated with the ion-trap qubit. The dynamics of a single mode k is described by a Landau–Zener crossing, that is implemented with a 171Yb+ ion confined in a Paul trap consisting of six needles placed on two perpendicular planes, as shown in Fig. 1a. The hyperfine clock transition in the ground state S1∕2 manifold is chosen to realize the qubit, with energy levels denoted by \(\left|0\right\rangle \equiv \left|F=0,\ {m}_{F}=0\right\rangle\) and \(\left|1\right\rangle \equiv \left|F=1,\ {m}_{F}=0\right\rangle\), as shown in Fig. 1b.

a A single 171Yb+ is trapped in a needle trap, which consists of six needles on two perpendicular planes. b The qubit energy levels are denoted by \(\left|0\right\rangle\) and \(\left|1\right\rangle\), which is the hyperfine clock transition of the trapped ion. c The qubit is driven by a microwave field, generated by a mixing wave scheme in the high-pass filter (HPF). Operations on the qubit are implemented by programming the arbitrary wave generator (AWG). The quantum critical dynamics of the one-dimensional transverse-field quantum Ising model is detected by measuring corresponding Landau–Zener crossings governing the dynamics in each mode.

State preparation and manipulation

At zero static magnetic field, the splitting between \(\left|0\right\rangle\) and \(\left|1\right\rangle\) is 12.642812 GHz. We applied a static magnetic field of 4.66 G to define the quantization axis, which changes the \(\left|0\right\rangle\) to \(\left|1\right\rangle\) resonance frequency to 12.642819 GHz, and creates a 6.5 MHz Zeeman splittings for 2S1/2, F = 1. In order to manipulate the hyperfine qubit with high control, coherent driving is implemented by a wave mixing method, see the scheme in Fig. 1c. First, an arbitrary wave generator (AWG) is programmed to generate signals ~200 MHz. Then, the waveform is mixed with a 12.442819 GHz microwave (generated by Agilent, E8257D) by a frequency mixer. After the mixing process, there will be two waves ~12.242 GHz and 12.642 GHz, so a high-pass filter is used to remove the 12.224 GHz wave. Finally, the wave ~12.642 GHz is amplified to 2 W and used to irradiate the trapped ion with a horn antenna.

Measurement

For a typical experimental measurement in a single mode, Doppler cooling is first applied to cool down the ion41. The ion qubit is then initialized in the \(\left|0\right\rangle\) state, by applying a resonant light at 369 nm to excite S1/2, F = 1 to P1/2, F = 1. Subsequently, the programmed microwave is started to drive the ion qubit. Finally, the population of the bright state \(\left|1\right\rangle\) is detected by fluorescence detection with another resonant light at 369 nm, exciting S1/2, F = 1 to P1/2, F = 0. Fluorescence of the ion is collected by an objective with a 0.4 numerical aperture. A 935 nm laser is used to prevent the state of the ion to jump to metastable states41. The initialization process can prepare the \(\left|0\right\rangle\) state with fidelity >99.9%. The total error associated with the state preparation and measurement is measured as 0.5% (ref. 42).

In the Supplementary Note 1, we rewrite the explicit Hamiltonian of the k-th mode as a linear combination of a single two-levels system7. In this way, experimentally, the Hamiltonian of a single k-mode can be explicitly mapped to a qubit Hamiltonian describing a two-level system driven by a chirped microwave pulse,

where ΩR = 4J/ℏ and \({\Delta }_{k}(t)=4J[g(t)+\cos k]/(\hslash \sin k)\) are the Rabi frequency and the detuning of the chirped pulse, respectively. To measure the excitations probability after a finite ramp with normalized quench parameter A = JτQ/ℏ, we can vary g(t) from −5 to 0. For this purpose, a chirped pulse with length of \({T}_{p}=5A{T}_{{\rm{R}}}\sin k\) and g(t) = 5t/Tp − 5 is used in the experiment, with TR = 1/ΩR denoting the Rabi time. A typical operation process driven by the programmed microwave is illustrated on the Bloch sphere, see Methods section for details. First, the qubit is prepared in the ground state of \({\hat{H}}_{k}^{{\rm{TLS}}}\) at g(0) = −5. Then, g(t) is ramped from −5 to 0 with quenching rate 1/τQ. Finally, the ground state of the final \({\hat{H}}_{k}^{{\rm{TLS}}}\) is rotated to qubit \(\left|0\right\rangle\), so that the excited state is mapped to \(\left|1\right\rangle\), which can be detected as a bright state. The measured excitation probability for different quench times is shown in Fig. 2.

The quantum critical dynamics of the one-dimensional transverse-field quantum Ising model is accessible in an ion-trap quantum simulator, which implements the corresponding Landau–Zener crossings governing the dynamics in each mode, labeled by wavevector k. The Rabi frequency ΩR = 4J/\(\hslash\) was set to 2π × 20 kHz in the experiment. For each value of the wavevector k, the excitation probability is estimated from 10,000 measurements. The shaded region describes the excitation probability predicted by the Landau–Zener formula. Deviations from the later become apparent for fast quench times, especially for large values of k. Error bars indicate the standard deviation over 10,000 measurements.

Full probability distribution of topological defects

From the experimental data, the distribution P(n) of the number of kink pairs is obtained using the characteristic function Eq. (5) of a Poisson binomial distribution, in which the probability pk of each Bernoulli trial is set by the experimental value of the excitation probability upon completion of the corresponding Landau–Zener sweep. This result is compared with the theoretical prediction valid in the scaling limit—the regime of validity of the KZM—in which P(n) approaches the normal distribution, away from the adiabatic limit36

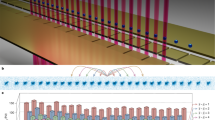

A comparison between P(n) and Eq. (7) is shown in Fig. 3. The matching between theory and experiment is optimal in the scaling limit far away from the onset of the adiabatic dynamics or fast quenches, for which nonuniversal corrections are expected. We further note that the onset of adiabatic dynamics enhances non-normal features of the experimental P(n) that cannot be simply accounted for by a truncated Gaussian distribution, that takes into account the fact that the number of kinks n = 0, 1, 2, 3, …

The experimental kink-pair number distribution for a transverse-field quantum Ising model with N = 100 spins is compared with the Gaussian approximation derived in the scaling limit, Eq. (7), ignoring high-order cumulants. The mean and width of the distribution are reduced as the quench time is increased. The experimental P(n) is always broader and shifted to higher kink-pair numbers than the theoretical prediction. Non-normal features of P(n) are enhanced near the sudden quench limit and at the onset of adiabatic dynamics. Error bars indicate the standard deviation over 10,000 measurements.

To explore universal features in P(n), we shall be concerned with the scaling of its cumulants κq (q = 1, 2, 3… ) as a function of the quench time. We focus on the first three, theoretically derived in the scaling limit in the Supplementary Note 2. The first one is set by the KZM estimate for the mean number of kink pairs κ1(τQ) = 〈n〉KZM. The second one equals the variance and as shown in the Supplementary Note 2 is set by \({\kappa }_{2}({\tau }_{{\rm{Q}}})={\rm{Var}}(n)=(1-1/\sqrt{2}){\langle n\rangle }_{{\rm{KZM}}}\). Finally, the third cumulant is given by the third centered moment \({\kappa }_{3}({\tau }_{{\rm{Q}}})=\langle {(n-\langle n\rangle )}^{3}\rangle =(1-3/\sqrt{2}+2/\sqrt{3}){\langle n\rangle }_{{\rm{KZM}}}\). Indeed, all cumulants are predicted to be nonzero and proportional to 〈n〉KZM (ref. 36), with the scaling of the first cumulant \({\langle n\rangle }_{{\rm{KZM}}}\propto {\tau }_{{\rm{Q}}}^{-\frac{1}{2}}\) being dictated by the KZM. We compared this theoretical prediction with the cumulants of the experimental P(n) in Fig. 4, represented by dashed lines and symbols, respectively. As discussed in the Supplementary Note 2, deviations from the power law occur at very fast quench times, satisfying τQ < ℏ/(π3J). However, this regime is not probed in the experiment, as all data points are taken for larger values of τQ. Within the parameters explored, deviations at fast quenches with JτQ/ℏ ~ 1 are due to the fact that the excitation probability pk in each mode is not accurately described by the Landau–Zener formula, as shown in Fig. 2. For moderate ramps, the power-law scaling of the cumulants is verified for q = 1, 2. The power-law scaling for κq(τQ) with q > 1 establishes the universal character of critical dynamics beyond the KZM. The later is explicitly verified for κ2(τQ), as shown in Fig. 4. Beyond the fast-quench deviations shared by the first cumulant, the power-law scaling of the variance of the number of kink pairs κ2(τQ) extends to all the larger values of the quench time explored, with barely noticeable deviations. By contrast, for the third cumulant κ3(τQ), the experimental data are already dominated by nonuniversal contributions both at short quench times, away from the scaling limit. For slow ramps, the third cumulant exhibits an onset of adiabatic dynamics due to finite-size effects around JτQ/ℏ = 102. Finite-size effects are predicted to lead to a sharp suppression of the third cumulant. However, the experimental data shows that κ3 starts to increase with τQ. This is reminiscent of the anti-KZ behavior that has been reported in the literature for the first cumulant in the presence of heating sources43,44, and we attribute it to noise-induced dephasing of the trapped-ion qubit. The nature of these deviations is significantly more pronounced in high-order cumulants, reducing the regime of applicability of the universal scaling.

The experimental data (symbols) are compared with the scaling prediction (dashed lines) and the numerical data (solid lines) for the first three cumulants with q = 1, 2, 3. The universal scaling of the first cumulant κ1(τQ) = 〈n〉 is predicted by the KZM according to Eq. (4). Higher-order cumulants are also predicted to exhibit a universal scaling with the quench time. All cumulants of the experimental P(n) exhibit deviations from the universal scaling at long quench times consistent with a dephasing-induced anti-KZM behavior. Further deviations from the scaling behavior are observed at fast quench times. The range of quench times characterized by universal behavior is reduced for high-order cumulants as q increases. The error bars are much smaller than the size of the symbols used to depict the measured points.

Discussion

In summary, using a trapped-ion quantum simulator we have measured the full distribution of topological defects in the quantum Ising chain, the paradigmatic model of quantum phase transitions, and characterized in detail its first three cumulants as a function of the quench rate. The statistics of the number of kink pairs have been shown to be described by the Poisson binomial distribution, with cumulants obeying a universal power law with the quench time, in which the phase transition is crossed. Our findings demonstrated that the scaling theory associated with a critical point rules the formation of topological defects beyond the scope of the KZM, which is restricted to the average number. Our work could be extended to probe systems with topological order, in which defect formation has been predicted to be anomalous45. We anticipate that the universal features of the full counting statistics of topological defects may be used in the error analysis of adiabatic quantum annealers, where the KZM already provides useful heuristics10.

Methods

A detailed description of analytical methods employed to obtain the results can be found in the Supplementary Information accompanying this work. In the following subsections, we present the experimental techniques employed.

Experimental mapping at two-level system

Hamiltonian of a single qubit driven by a microwave field is given by Eq. (6). In the experiment, the Rabi frequency of the qubit simulator is set ~20 kHz, which depends on the driven power of our microwave amplifier. The higher microwave power can shorten the Rabi time TR = 1/ΩR, and reduce the total operation time. To simulate the quenching process, one would like to vary g from −∞ to 0, an idealized evolution that needs infinite time, which cannot be realized in the experiment. However, to explore the universality associated with the crossing of the critical point one can initialize the system sufficiently deep in the paramagnetic phase. According to the KZM, it is sufficient to choose an initial value of the magnetic field such that the corresponding equilibrium relaxation time is much smaller than the time left until crossing the critical point. The system is then prepared out of the “frozen region” in the language of the adiabatic-impulse approximation7. For the quench time τQ ≥ 1, the initial value of g = −5 is far out of the frozen time. We can simulate the TFQIM with an initial g = −5 and no excitations, by preparing the initial state of the qubit in the ground state of \({\hat{H}}_{k,i}^{s}={\hat{H}}_{k}^{s}(g=-5)\) before the quenching process. The initial state can be derived by solving the eigenvectors of Eq. (6), which is

where \({\theta }_{k,i}=-\!\arctan \frac{\sin \left(ka\right)}{5\,{+}\, \cos \left(ka\right)}\).

The scheme to detected the quantum critical dynamics of the one-dimensional TFQIM in each mode by using a single qubit is shown in Fig. 5. The whole process can be divided to three steps. Before the process, the qubit has been pumped to \(\left|0\right\rangle\) state by using a 369 nm laser to excite transition S1∕2, F = 1 → P1/2, F = 1. In the first stage, the ion-trap qubit is prepared into the state \({\left|{\psi }_{\!-\!}\right\rangle }_{k,i}\) by a resonant microwave pulse. The second stage is the quench process; the Hamiltonian is time dependent and varies from \({\hat{H}}_{k,i}^{s}\equiv {\hat{H}}_{k}^{s}(g=-5)\) to \({\hat{H}}_{k,f}^{s}\equiv {\hat{H}}_{k}^{s}(g=0)\). This is implemented by applying a chirped microwave pulse to the qubit. The chirped pulse is in the form of \({\Delta }_{k}(t)=4J\frac{g\left(t\right)\,-\,\cos \left(ka\right)}{\hslash \sin \left(ka\right)}\) with g(t) = 5(t/Tp − 1), where \({T}_{p}=5J{\tau }_{{\rm{Q}}}\sin (ka)/\left(\hslash {\Omega }_{R}\right)\) is the pulse length. The third stage is to measure the excitation probability after the quench, which is to measure the occupation probability on the excited eigenstate of \({\hat{H}}_{k,f}^{s}\). The excited eigenstate is \({\left|{\psi }_{\!-\!}\right\rangle }_{k,f}=\sin \frac{{\theta }_{k,f}}{2}\left|0\right\rangle +\cos \frac{{\theta }_{k,f}}{2}\left|1\right\rangle\), where θk,f = −ka. As the fluorescence detection on 171Yb+ can only discriminate \(\left|0\right\rangle\) and \(\left|1\right\rangle\) sates, we need to rotate the state \({\left|{\psi }_{-}\right\rangle }_{k,f}\) to \(\left|1\right\rangle\) and then detect the bright state probability. We thus use a qubit rotation and a fluorescence detection in this stage. The calculated waveform to set the AWG to perform the prerotation, quench and postrotation in the three stages will be discussed in the next section.

Driving waveform with an AWG

We consider the driving microwave from AWG is \(A\cos ({\omega }_{c}t+{\it{\Phi}} (t))\), where A is the amplitude, ωc is the carrier frequency, and Φ(t) is an arbitrary phase function. The carrier frequency can be mixed up with some frequency ω0 from a local oscillator by using a frequency mixer. The waveform at the output of the mixer is

When the wave passes through the high-pass filter, the waveform is filtered as \(A/2\cos (({\omega }_{o}+{\omega }_{c})t+{\it{\Phi}} (t))\). In the experiment, we choose the frequency ωo + ωc resonant with the qubit transition ωQ = ωo + ωc, so the magnetic field of the final driving waveform is \({\bf{B}}(t)={{\bf{B}}}_{{\bf{0}}}\cos ({\omega }_{Q}t+{\it{\Phi}} (t))\). The interaction between the magnetic field and spin is HI = −μ ⋅ B, where μ is the magnetic dipole of the spin qubit. The Hamiltonian can be further simplified after the rotating wave approximation in the interaction frame

where the Rabi frequency \({\Omega }_{R}=-\left\langle 0\right|{{\mu }}\cdot {\bf{B}}\left|1\right\rangle /\hslash\). The phase function Φ(t) corresponds to the azimuthal angle in the Bloch sphere. Equation (6) can be also expressed in interaction frame

so in the quench stage, the phase function is

We rotate the state along a vector in the equatorial plane to prepare a state from \(\left|0\right\rangle\), or measure state to \(\left|1\right\rangle\), which means Φ(t) is constant in these two stages. The pulse length for the preparation and measurement stages is determined by the polar angle of the ground state at the beginning and end of the quench process, t = θ∕ΩR, respectively. The whole expression of Φ(t) in the three stages can be derived as

where t1 = (2π − θk,i)/ΩR, t2 = t1 + Tp, t3 = t2 + (2π + θk,f)/ΩR, and \({\phi }_{f}=-5{\tau }_{{\rm{Q}}}(2.5+\cos ka)\).

Qubit preparation and detection error

There are some limitations to the preparation and measurement of the qubit. We measured the error through a preparation and detection experiment. First, we prepare the qubit in the \(\left|0\right\rangle\) state by optical pumping method and detect the ion fluorescence. Ideally, no photon can be detected as the ion is in the dark state. However, there are dark counts of the photon detector as well as photons scattered from the environment. We repeat the process 105 times, and estimate the detected photon numbers. We also repeat the process 105 times by preparing the qubit in the bright state. Histograms for the photon number in the dark and bright states are shown in Fig. 6. In the experiment, the threshold is selected as 2: the state of the qubit is identified as the bright state when the detected photon number is ≥2. There is a bright error ϵB for the dark state above the threshold, and a dark error ϵD for the bright state below the threshold. The total error can be take as ϵ = (ϵB + ϵD)/2.

Data availability

The data that support the plots and other findings within this paper are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Kibble, T. W. B. Topology of cosmic domains and strings. J. Phys. A: Math. Gen. 9, 1387 (1976).

Kibble, T. W. B. Some implications of a cosmological phase transition. Phys. Rep. 67, 183–199 (1980).

Zurek, W. H. Cosmological experiments in superfluid helium? Nature 317, 505–508 (1985).

Zurek, W. H. Cosmological experiments in condensed matter systems. Phys. Rep. 276, 177–221 (1993).

Polkovnikov, A. Universal adiabatic dynamics in the vicinity of a quantum critical point. Phys. Rev. B 72, 161201 (2005).

Damski, B. The simplest quantum model supporting the kibble-zurek mechanism of topological defect production: Landau-zener transitions from a new perspective. Phys. Rev. Lett. 95, 035701 (2005).

Dziarmaga, J. Dynamics of a quantum phase transition: exact solution of the quantum Ising model. Phys. Rev. Lett. 95, 245701 (2005).

Zurek, W. H., Dorner, U. & Zoller, P. Dynamics of a quantum phase transition. Phys. Rev. Lett. 95, 105701 (2005).

del Campo, A. & Zurek, W. H. Universality of phase transition dynamics: topological defects from symmetry breaking. Int. J. Mod. Phys. A 29, 1430018 (2014).

Suzuki, S. Quench Dynamics of Quantum and Classical Ising Chains: From the Viewpoint of the Kibble–Zurek Mechanism, 115–143 (Springer Berlin Heidelberg, Berlin, Heidelberg, 2010).

Hendry, P. C., Lawson, N. S., Lee, R. A. M., McClintock, P. V. E. & Williams, C. D. H. Generation of defects in superfluid 4he as an analogue of the formation of cosmic strings. Nature 368, 315–317 (1994).

Ruutu, V. M. H. et al. Vortex formation in neutron-irradiated superfluid 3he as an analogue of cosmological defect formation. Nature 382, 334–336 (1996).

Bäuerle, C., Bunkov, Y. M., Fisher, S. N., Godfrin, H. & Pickett, G. R. Laboratory simulation of cosmic string formation in the early universe using superfluid 3he. Nature 382, 332–334 (1996).

Chuang, I., Durrer, R., Turok, N. & Yurke, B. Cosmology in the laboratory: defect dynamics in liquid crystals. Science 251, 1336–1342 (1991).

Bowick, M. J., Chandar, L., Schiff, E. A. & Srivastava, A. M. The cosmological kibble mechanism in the laboratory: string formation in liquid crystals. Science 263, 943–945 (1994).

Casado, S., González-Viñas, W., Mancini, H. & Boccaletti, S. Topological defects after a quench in a bénard-marangoni convection system. Phys. Rev. E 63, 057301 (2001).

Casado, S., González-Viñas, W. & Mancini, H. Testing the kibble-zurek mechanism in rayleigh-bénard convection. Phys. Rev. E 74, 047101 (2006).

Monaco, R., Mygind, J. & Rivers, R. J. Zurek-kibble domain structures: the dynamics of spontaneous vortex formation in annular josephson tunnel junctions. Phys. Rev. Lett. 89, 080603 (2002).

Monaco, R., Mygind, J., Aaroe, M., Rivers, R. J. & Koshelets, V. P. Zurek-kibble mechanism for the spontaneous vortex formation in Nb–Al/alox/Nb josephson tunnel junctions: new theory and experiment. Phys. Rev. Lett. 96, 180604 (2006).

Weir, D. J., Monaco, R., Koshelets, V. P., Mygind, J. & Rivers, R. J. Gaussianity revisited: exploring the kibble–zurek mechanism with superconducting rings. J. Phys.: Condens. Matter 25, 404207 (2013).

Ulm, S. et al. Observation of the Kibble–Zurek scaling law for defect formation in ion crystals. Nat. Commun. 4, 2290 (2013).

Pyka, K. et al. Topological defect formation and spontaneous symmetry breaking in ion coulomb crystals. Nat. Commun. 4, 2291 (2013).

Ejtemaee, S. & Haljan, P. C. Spontaneous nucleation and dynamics of kink defects in zigzag arrays of trapped ions. Phys. Rev. A 87, 051401 (2013).

Deutschländer, S., Dillmann, P., Maret, G. & Keim, P. Kibble-Zurek mechanism in colloidal monolayers. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 112, 6925–6930 (2015).

Weiler, C. N. et al. Spontaneous vortices in the formation of bose-einstein condensates. Nature 455, 948–951 (2008).

Lamporesi, G., Donadello, S., Serafini, S., Dalfovo, F. & Ferrari, G. Spontaneous creation of kibble-zurek solitons in a bose-einstein condensate. Nat. Phys. 9, 656 (2013).

Chomaz, L. et al. Emergence of coherence via transverse condensation in a uniform quasi-two-dimensional bose gas. Nat. Commun. 6, 6162 (2015).

Navon, N., Gaunt, A. L., Smith, R. P. & Hadzibabic, Z. Critical dynamics of spontaneous symmetry breaking in a homogeneous bose gas. Science 347, 167 (2015).

Ko, B., Park, J. W. & Shin, Y. Kibble-zurek universality in a strongly interacting fermi superfluid. Nat. Phys. 15, 1227–1231 (2019).

del Campo, A., Kibble, T. W. B. & Zurek, W. H. Causality and non-equilibrium second-order phase transitions in inhomogeneous systems. J. Phys.: Condens. Matter 25, 404210 (2013).

Gómez-Ruiz, F. J. & del Campo, A. Universal dynamics of inhomogeneous quantum phase transitions: suppressing defect formation. Phys. Rev. Lett. 122, 080604 (2019).

Xu, X.-Y. et al. Quantum simulation of landau-zener model dynamics supporting the kibble-zurek mechanism. Phys. Rev. Lett. 112, 035701 (2014).

Cui, J.-M. et al. Experimental trapped-ion quantum simulation of the kibble-zurek dynamics in momentum space. Sci. Rep. 6, 33381 (2016).

Gong, M. et al. Simulating the kibble-zurek mechanism of the ising model with a superconducting qubit system. Sci. Rep. 6, 22667 (2016).

Bernien, H. et al. Probing many-body dynamics on a 51-atom quantum simulator. Nature 551, 579 (2017).

del Campo, A. Universal statistics of topological defects formed in a quantum phase transition. Phys. Rev. Lett. 121, 200601 (2018).

Sachdev, S. Quantum Phase Transitions 2nd edn (Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2011).

Jordan, P. & Wigner, E. Über das paulische äquivalenzverbot. Zeitschrift für Physik 47, 631–651 (1928).

Barouch, E. & McCoy, B. M. Statistical Mechanics of the XY Model. II. Spin-Correlation Functions. Phys. Rev. A 3, 786–804 (1971).

Chakrabarti, B.K., Dutta, A. & Sen, P. Quantum Ising Phases and Transitions in Transverse Ising Models, Vol. 41 (Springer-Verlag, Berlin, 1996).

Olmschenk, S. et al. Manipulation and detection of a trapped Yb+ hyperfine qubit. Phys. Rev. A 76, 052314 (2007).

Blume-Kohout, R. et al. Demonstration of qubit operations below a rigorous fault tolerance threshold with gate set tomography. Nat. Commun. 8, 14485 (2017).

Griffin, S. M. et al. Scaling behavior and beyond equilibrium in the hexagonal manganites. Phys. Rev. X 2, 041022 (2012).

Dutta, A., Rahmani, A. & del Campo, A. Anti-kibble-zurek behavior in crossing the quantum critical point of a thermally isolated system driven by a noisy control field. Phys. Rev. Lett. 117, 080402 (2016).

Bermudez, A., Patanè, D., Amico, L. & Martin-Delgado, M. A. Topology-induced anomalous defect production by crossing a quantum critical point. Phys. Rev. Lett. 102, 135702 (2009).

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge funding support from the National Key Research and Development Program of China (nos. 2017YFA0304100 and 2016YFA0302700), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (nos. 61327901, 11774335, 11474268, 11734015, and 11821404), Key Research Program of Frontier Sciences, CAS (no. QYZDY-SSW-SLH003), the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (nos. WK2470000026, WK2470000027, and WK2470000028), Anhui Initiative in Quantum Information Technologies (nos. AHY020100 and AHY070000), and John Templeton Foundation.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.d.C. proposed the project and developed the theoretical framework. J.-M.C. and Y.-F.H. took the experimental measurements. F.J.G.-R. developed numerical simulations and prepared the figures. All authors contributed to the analysis of the results and the writing of the manuscript. C.-F.L., G.-C.G., and A.d.C. supervised the project.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Cui, JM., Gómez-Ruiz, F.J., Huang, YF. et al. Experimentally testing quantum critical dynamics beyond the Kibble–Zurek mechanism. Commun Phys 3, 44 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s42005-020-0306-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s42005-020-0306-6

This article is cited by

-

Kibble–Zurek scaling due to environment temperature quench in the transverse field Ising model

Scientific Reports (2023)

-

Coherent quantum annealing in a programmable 2,000 qubit Ising chain

Nature Physics (2022)

-

Universal statistics of vortices in a newborn holographic superconductor: beyond the Kibble-Zurek mechanism

Journal of High Energy Physics (2021)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.