Abstract

A pressing quest for overcoming Boltzmann tyranny in low-power nanoscale electronics ignited an extensive search for the devices possessing the negative circuit constants. The emergent concept of the ferroelectric-based negative capacitance triggered then the explosive activity in the field. However, most of the research addressed transient negative capacitance, leaving the basic question of the existence of the steady-state negative capacitance unresolved. Here, we show that the ferroelectric nanodot capacitor hosts a stable two-domain state realizing the static reversible negative capacitance device thus opening routes for the extensive use of the negative capacitance in domain wall-based nanoelectronics.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Over 40 years ago, Rolf Landauer raised the question whether the capacitance can be negative1, that is if the increase in the charge of the capacitor can decrease its voltage. Having stated that ferroelectrics (FE) can harbor the negative capacitance (NC) during the transient processes of switching, Landauer indicated that the very existence of the static NC as a part of steady state is challenged by instability against spontaneous domain formation. The followed extensive search for low-dissipating electronics revived the thoughts of engineers of early 1930s on the possibility of negative circuit constants2,3,4. The idea of the FE-based NC devices5, 6 triggered explosive activity in the field, see7,8,9 for review. However, most of the research addressed transient NC, leaving the basic question of the existence of the steady-state NC unresolved.

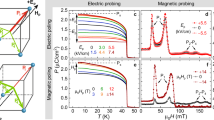

Negative capacitance would naturally arise in the Landau description of the uniformly polarized FE, where the free energy, F as a function of polarization, P, or capacitor charge, Q, assumes a double well form, see Fig. 1a. A standard approach, based on the minimization of F at the given voltage V, yields the dependence Q(V), where the induced charge represents the system's response to the applied voltage. The resulting charge–voltage characteristic has the form of an S-shaped curve, GABCDEF, shown in Fig. 1b. Being driven by the applied voltage, the capacitor switches between the two stable branches GAB and DEF, corresponding to the up- and down-oriented FE polarizations, in a hysteretic fashion. The differential capacitance, C = dQ/dV, is positive when the system falls into either of these two polarized states. Remarkably, C reverses its sign when the system traverses along the intermediate branch BCD, having the negative slope. However, since the BCD path of the Q(V) dependence corresponds to the concave segment in the energy profile (Fig. 1a), this intermediate branch of the S-curve is unstable, hence the static NC regime is unreachable for a voltage-driven capacitor.

The ferroelectric capacitor (FE) with negative capacitance (NC). a The plot of the Landau functional describing the free energy of the FE capacitor, F as function of its charge, Q. b The charge–voltage characteristic, Q–V, corresponding to the Landau free energy shown in a. The blue lines in both a, b correspond to the monodomain state, while the segments corresponding to the two-domain state with static NC are shown in orange. The dashed green curves on b depict the polarization switching process manifesting the transient NC. c Ferrolelectric monodomain sample. Termination of polarization, P (black arrow), at the surface of the sample implies the emergence of the surface depolarization charges, which induce the depolarization field E shown in red, directed opposite to the polarization. d Formation of the periodic domain structure with the up-/down-oriented polarization and alternating surface depolarization charge, reduces the energy of a FE as compared to the energy of the uniformly polarized state. e The FE sample with short-circuited electrodes. Redistribution of the electric charge between electrodes screens the depolarization field, thus zeroing the depolarization energy. As a result, the monodomain structure with uniform polarization is recovered. f In the FE sample confined between two neutral disconnected electrodes, screening of the depolarization charges occurs if the uniform polarization transforms into two equal-size domains with the oppositely oriented polarizations. Free electrons redistribute inside the electrodes to preserve their electroneutrality. g Top view of the two-domain structure with disconnected electrodes. Both FE domains have equal surface areas S1 = S2. h Adding the charge, Q, reconfigures the depolarization charges that tend to maintain the field from the electrodes screened. This is achieved by displacing and bending the domain wall (DW) accompanied by the repartition of the areas of the respective domains. Since the DW shrinks upon approach to the edge of the nanodot, the surface tension pulls the DW out of the system to decrease its surface energy. This additional force drags DW slightly beyond its location that would have ensured the complete screening, leading to the peculiar “overscreening effect”. In such a configuration, the compensating depolarization field exceeds the field from the electrodes, hence the residual field appears to be directed oppositely to the polarization of the nanodot. This is what constitutes the NC effect. i Top view of the FE capacitor with the displaced DW. j Negative differential permittivity εf of the cylindrical FE PbTiO3 nanodot capacitors of different radii as functions of the charge density, Q/S. The jumps in εf from the negative to positive value mark the full polarization of the nanodot to the monodomain state

In an experiment, the switching instability may occur even before the system reaches the turning points B and D as a result of the reverse domain nucleation and the accelerated growth. The corresponding temporal evolution of the charge and voltage drop would then follow the dynamical Q(V) trajectory, depicted by B′F and D′G dashed segments in Fig. 1b, with the negative slope at the beginning of the switching10. This negative slope is commonly viewed as a manifestation of the NC6, 9, 11. Most of the described devices work in this transient regime of switching6, 8, 12,13,14. However, the irreversibility of the switching hysteresis complicates practical implementation of the existing NC devices and impedes their applications to engineering the next generation of ultrafast low-power transistors. Several publications communicate the nearly hysteresis-free sub-60-mV/decade subthreshold swing in transistors with FE gates15,16,17, which indicate the possibility of the NC in the reported devices5. However, no dependencies Q(V) are as yet available there, which hinders a straightforward physical interpretation of these findings. There are remarkably encouraging recent reports by Saedi et al.18, 19, in which the dependence Q(V), measured in FE transistor, suggests the existence of the nonhysteretic NC, likely related with the domain dynamics. These observations call for qualitative and quantitative understanding of the physics of devices capable of supporting the stable and reversible static NC.

What stabilizes the static NC in the intermediate branch of the S-curve is setting the charge, Q, as a driving parameter controlling the state of the capacitor, so that it is V that becomes the system's response1, 5. This would reverse the S-shaped Q(V) dependence of the monodomain FE state into an N-shaped V(Q) function that maintains the negative sign of dQ/dV at low Q but has no bistability anymore. Yet, however attractive, this approach may not to straightforwardly work since the charge-driven system would likely split into the multidomain state1. For instance, the paraelectric uniform state C at Q = 0 will break up into the lower-energy FE states A and E comprising the domains with alternating oppositely oriented polarization. This effect is often thought to be detrimental to steady state NC20, 21.

However, the situation appears not that hopeless once the delicate balance between the domain wall (DW) and electric field energies is cleverly taken into account. To see that, let us consider the mechanism of domain formation in a FE sample more in details. The spontaneous polarization, P0, inside the monodomain FE flat cell with uniaxial anisotropy generates the depolarization surface charges, +P0, at the top and −P0 at the bottom of the cell, which induce the depolarization field Edep = −P0/ε0ε||, directed opposite to the polarization (Fig. 1c). Here, ε|| is the permittivity of the FE material along P, and ε0 is the absolute perimittivity of the vacuum. An additional energy associated with this field disfavors the uniform polarization and splits the system into the alternating sequence of the up-/down-polarized domains (Fig. 1d). Such a domain texture was found in the FE dielectric (FE-DE) heterostructures22,23,24,25,26. It was further demonstrated27,28,29, that the FE layers harboring domains possess a negative permittivity, i.e., the average intrinsic field there is directed opposite to the electrostatic displacement. However this negative permittivity effect as is remains hard to utilize for a NC device, since the metallic electrodes when placed on the surfaces of the FE layer would effectively screen the depolarization fields induced by domains and the domains themselves would disappear right off (Fig. 1e).

Our work takes up on the task and presents a conceptual design of the device enabling the stable and reversible static NC that corresponds to the negative slope of the intermediate branch of the S-curve, Q(V). We demonstrate that the problem of the implementation of the steady reversible NC is achieved by about 10 nm nanodot FE capacitor, endowed with the two-domain ground state. Splitting the monodomain state into the two-domain ground state and the subsequent motion of the DW, results in the modified free energy curve and corresponding modification of the Q(V) dependence shown by orange curves in Fig. 1a, b. These characteristics retains the features of the S-curve of the monodomain system, hence the steady state NC.

Results

The model

We consider, for concreteness, the cylindrical FE nanodot of radius R and thickness df < 2R sandwiched between the metallic electrodes that are not connected neither with each other nor with the external source of the electrons. Let the charge at the electrodes of the FE capacitor be zero, Q = 0, Fig. 1f. Then the energy of the system is indeed minimized by splitting the system into the two equal-size domains with equal surfaces S1 = S2 = S/2, with S = πR2, and down-/up-directed polarizations, −P0, and +P0 (Fig. 1g). These oppositely oriented polarizations generate surface depolarization charges of the corresponding densities ∓P0 at the top surface of the FE cell and the charges of the opposite signs at the bottom surface. This, in turn, induces redistribution of the free charges in the electrodes to compensate electric fields of the surface depolarization charges. Since the domains are of the equal size, the electroneutrality of the electrodes, Q = 0, is preserved and the average polarization and the corresponding depolarization charges are zero. As the price to pay for eliminating the depolarization energy is the DW energy, the least energy cost is provided by splitting the bulk of the FE capacitor into the two equal-size domains with the minimal area of the DW. Since the depolarization energy is proportional to the volume of the system, whereas the DW energy cost is proportional to its area, the splitting into domains provides the gain in energy and drives the system into the stable state.

Adding the charge on electrodes, shifts the DW, which finds the corresponding new equilibrium position (Fig. 1h). To immediately see that the FE capacitor harboring the two-domain state has a negative capacitance we note, that if one short-circuited the plates, allowing for the free electrons to flow between the plates and charge the capacitor to allow to compensate the uniform depolarization field, the DW exits from the system which thus transits into the monodomain state with the lower energy Fig. 1e. This self-charging effect manifests the emergence of the NC. For the evaluation of the NC, let us place the small test charges, +Q on the top electrode and −Q on the bottom electrode of the FE capacitor, Fig. 1h, (the electrodes are disconnected) and follow its response. Charging the capacitor causes the displacement of the DW in such a way that the depolarization field arising due to the misbalance of the domain surfaces, S1 and S2, (Fig. 1i) would screen the electrical field induced by the test charges. Upon deviating from the initial position at the center and assuming the new equilibrium position, the DW acquires a cylindrical-arc shape that minimizes the DW surface tension energy (Fig. 1i). The arc makes the right contact angle with the nanodot surface to eliminate the tangential drag caused by the surface tension, see Supplementary Note 1.

Crucially, the new equilibrium position of the DW lies beyond the location that would correspond to the exact compensation of the electric field. The reason is that in a finite cylindrical system, this extra displacement further decreases the surface of the DW, and therefore provides an extra gain in energy. Because of this “overshooting” effect, the total charge at the upper electrode becomes negative, while the charge at the bottom electrode becomes positive, see Fig. 1h. As a result, the internal electrical field E reverses its direction with respect to the field induced by the injected charges, which is the physical origin of the NC.

Calculations

To carry out a quantitative analysis, we calculate the internal field, E, see Supplementary Note 2, and find the integral capacitance as \(\tilde C_{\mathrm{f}} \equiv Q{\mathrm{/}}V\) where V = −dfE is the potential difference between the top and bottom electrodes; we use the tilde to distinguish \(\tilde C_{\mathrm{f}}\) from the differential capacitance Cf ≡ dQ/dV.

We obtain the integral FE capacitance in a standard form with the negative, integral permittivity \(\tilde \varepsilon _{\mathrm{f}}\), see Supplementary Note 3 for details:

The integral permittivity, \(\tilde \varepsilon _{\mathrm{f}}\), is a fundamental characteristic of the FE nanodot and appears also in the expression for the polarization curve, \(P(E) = \varepsilon _0\left( {\tilde \varepsilon _{\mathrm{f}} - 1} \right)E\). The dimensionless function ψ(Q) reflects the nonlinear charging effects, see Supplementary Note 3. At small Q → 0, one finds \(\tilde \varepsilon _{\mathrm{f}} \approx - \frac{8}{{3\pi \nu }}\frac{R}{{\xi _0}}\varepsilon _{||}\). The dimensionless parameter ν ≃ wDW/wf, with \(w_{\mathrm{f}} \simeq 2\xi _0P_0^2{\mathrm{/}}\varepsilon _0\varepsilon _{||}\), characterizes the energy cost for the formation of the DW normalized to the bulk energy of the FE stored in the volume occupied by the DW. As a specific example, we consider the FE material PbTiO3 with ε|| ≃ 50 and ν ≃ 0.1, which is computed by the phase-field calculations, described in Methods. The DW width is taken of order of the FE coherence length ξ0 ≃ 1 nm.

Equation (1) that demonstrates the negative capacitance and permits to find the Q–V and P–E characteristics of the FE capacitor is the central result of our work. It permits also to find the experimentally measured differential capacitance and the effective differential permittivity, related with the corresponding integral parameters via \(C_{\mathrm{f}} = \tilde C_{\mathrm{f}} + V\left( {{\mathrm{d}}\tilde C_{\mathrm{f}}{\mathrm{/}}{\mathrm{d}}V} \right)\), \(\varepsilon _{\mathrm{f}} = \tilde \varepsilon _{\mathrm{f}} + E\left( {{\mathrm{d}}\tilde \varepsilon _{\mathrm{f}}{\mathrm{/}}{\mathrm{d}}E} \right)\). The behavior of the differential permittivity, as a function of the charge density, is shown in Fig. 1j for cylindrical nanodots of PbTiO3 of radius R = 2, 5, and 10 nm, respectively. The interval of the NC is extended over all range of the domain existence. The jumps in the εf from the negative to the positive values correspond to the complete polarization of the FE capacitor to the monodomain state.

Numerical simulations

We carry out the phase field modeling of the FE capacitor, consisting of the cylindrical FE nanodot of PbTiO3 sandwiched between two thin metallic electrodes and the SrTiO3 substrate. The latter induces the compressive strain of the nanodot ensuring the out-of-plane orientation of the polarization. The approach rests on the relaxation minimization of the strain-renormalized Landau–Devonshire functional, see Methods. The response of the 5 nm thick cylindrical FE capacitor of radius R = 5 nm with the two-domain structure to the variations in charge Q placed on the electrodes, is shown in Fig. 2a. In compliance with the model considerations described above, the DW departs from its bisector position at Q = 0 (state (1)), traversing the sample with simultaneous bending (state (2)). Finally the DW exits the sample (state (3)), leaving behind the uniformly polarized monodomain state. The corresponding P–E characteristics of the FE capacitors of different sizes and shapes are shown in the Fig. 2b. Importantly, the negative slope of the P(E) dependencies, that manifest the NC, maintains well beyond the linear regime at E ~ 0 and holds during the entire process of the motion of the DW. Therefore, the NC extends over the entire electric field interval from zero to the coercive threshold where the DW leaves the sample and the P–E characteristics turn around into the standard behavior of the monodomain sample. At variance, the multidomain-state nucleation switching process9, 11, resulting in the transient differential NC as well as in the charge-controlled single nanodomain formation30, resulting in the static differential NC, occur in the intermediate vicinity of the coercive field and far from the zero-field steady-state, see Fig. 1b. Inset in Fig. 2b demonstrates the jerky character of the dynamics of the DW due to pinning effects, see Supplementary Movie 1.

Polarization P–E characteristics for the FE nanodot capacitor. a The two-domain polarization distribution in the compressive-strained ferroelectric (FE) PbTiO3 nanodot of radius R = 5 nm and thickness df = 5 nm as function of the electric charge, Q, on the electrodes is obtained by the phase-field simulations. The configurations (1)–(3) correspond to points (1)–(3) in the P(E) plot shown in b. The color is used to mark the value of the z-component of the polarization, with red corresponding to the up- and blue corresponding to the down-oriented polarization. The intermediate green color portrays the domain wall (DW) itself. Yellow arrows indicate directions of the polarization. The orange rim depicts the bottom electrode, the top electrode is not shown. (1) At Q = 0 the areas of both domains are equal. (2) Displacement and bending of the DW at finite Q. (3) On the brink of the complete disappearance of the up-oriented domain at some precritical value of Q, the DW is ready to leave the sample and becomes strongly curved. b The P–E characteristics for 5 nm thick nanodots of various lateral sizes and shapes are shown by different colors. The corresponding theoretical curves are shown by solid lines. The zigzag behavior reflects the jerky motion of the DW due to pinning effects. The details of the pinning-induced behavior are displayed by the animation for the rectangular nanodot, see Supplementary Movie 1. The inset shows magnified P(E) plots at small values of E illustrating the development of the serration with the increasing nanodot size. For comparison, we present the results for quenching the nanodot from the paraelectric phase (blue dots)

For cylindrical nanodots, the negative slope of P(E) decreases with the decreasing nanodot's radius. The theoretical dependencies P(E), calculated from Eq. (1), are shown by solid lines. They perfectly describe the results of simulations except for the smallest 2 nm sample where the DW width is of order of the sample size. Similarly, it is the finite size of the DW that results in the slight deviation of the experimental behaviors from the theoretical predictions at the moment of the exit when the with of the DW compares to the size of the already nearly disappearing residual domain.

For the rectangular nanodot, the nearly infinite slope of P(E) reflects that the energy of the parallel-displaced straight DW almost does not depend on its position. The jump to the more shallow negative-slope dependence P(E) in the pre-critical region corresponds to the abrupt re-orientation of the DW from the parallel to the edge- to the corner-enclosing configuration (see Supplementary Movie 1 for the animation).

Discussion

Having found the Q–V characteristics of the FE capacitor we are now equipped to include it into an amplifying NC circuit. A sketch of the proposed device is shown in Fig. 3a. The capacitor consists of DE and FE cylindrical nanodots, consequently grown on the insulating substrate and partitioned by the platelet metallic electrodes. The equivalent circuit (Fig. 3b), which is a customary proposed model implementation of the NC low-dissipation field-effect transistor5, 20, comprises the two in-series capacitors, FE and DE with capacitances \(\tilde C_{\mathrm{f}} \ < \ 0\) and Cd > 0, respectively. An effect of the in-series capacitance circuit is that it enables the required charge-controlled operational mode. Namely, the operating voltage, Vin, applied to the top gate electrode, controls the charge of the system Q = Q(Vin), via the relation \(V_{{\mathrm{in}}} = \left( {\tilde C_{\mathrm{f}}^{ - 1} + C_{\mathrm{d}}^{ - 1}} \right)Q\), which establishes correspondence between Vin and Q. This mode is stable and reversible as long as capacitances \(\tilde C_{\mathrm{f}}\) and Cd are matched, providing the circuit capacitance \(C_{{\mathrm{circ}}} = 1{\mathrm{/}}\left( {\tilde C_{\mathrm{f}}^{ - 1} + C_{\mathrm{d}}^{ - 1}} \right) > 0\), therefore, the total energy of the circuit, \(U = C_{{\mathrm{circ}}}V_{{\mathrm{in}}}^{\mathrm{2}}{\mathrm{/}}2\) is positive, which lifts a seeming paradox of the negative capacitance. In this field-effect transistor, the output voltage drop on the DE layer, Vout, is collected from the middle electrode, while the bottom electrode is grounded. Once \(\tilde C_{\mathrm{f}}\) is negative and Cd is positive, then applying the input voltage, Vin, results in the amplification of Vout given by \(V_{{\mathrm{out}}} = \tilde m^{ - 1}V_{{\mathrm{in}}}\), where \(\tilde m = 1 + C_{\mathrm{d}}{\mathrm{/}}\tilde C_{\mathrm{f}} < 1\) is the so-called body factor5 and \(\tilde C_{\mathrm{f}}(Q)\) is given by Eq. (1) with Q = CdVout.

The negative capacitance (NC)-based amplifying circuit and its characteristics. a The device has a substrate-deposited Big Mac structure comprising the ferroelectric (FE) (carrying up- and down-polarization domains, shown by the red and dark blue, respectively and separated by the green domain wall (DW)), and the dielectric (DE) (light blue) nanoplatelets. The FE and DE layers are confined between the three-parts electrode shown in orange, the top, intermediate, and bottom ones. The substrate is shown by the blue-gray. The top electrode, the strained uniaxial FE layer, and the intermediate electrode constitute the FE capacitor. The negative capacitance stems from the displacement of the DW in the FE capacitor. The DE capacitor comprises the ultrahigh-ε material. The bottom electrode is grounded. The input voltage, Vin, is applied to the cover top electrode. The output voltage, Vout, is collected from the DE capacitor and exceeds the input voltage, Vout > Vin. b The equivalent scheme of the circuit with Cf < 0 corresponding to the FE and Cd > 0 corresponding to the DE capacitors. c The plots Vout(Vin) corresponding to different radii of PbTiO3 nanodots contain three distinct segments: (i) linear parts which correspond to the displacing DW and reflect the amplifying effect (since the curves lie above the bissectrix Vout = Vin), (ii) the reverse parts corresponding to the unstable DW, and (iii) the flattened positive-slope-parts corresponding to the monodomain state response. The inset demonstrates the differential body factors, m = (dVout/dVin)−1, plotted as a function of Vin

Figure 3c shows, how the output voltage Vout depends on the driving voltage Vin for PbTiO3/SrTiO3 cylindrical nanodots of radii R = 2, 5, and 10 nm, in which the DE layer is about half thin compared to the FE one, and Cd = ε0εdS/dd with εd ≃ 300 for SrTiO3. The working range of the device is confined between the negative and positive reverse points in the middle branch of Vout(Vin) curves where the two-domain state is locally stable. The reversal segments correspond to the unstable situation when the DW comes out from the sample. The upper and lower branches of the curves reflect the monodomain states with the positive differential capacity. As the working part of the Vout(Vin) dependence corresponding to the two-domain state lies above the Vout = Vin bisectrix, the device exhibits the amplification effect, which, in the linear approximation, is given by the body factor

For nanodots with R = 5 nm the estimate gives \(\tilde m \simeq 0.69\), which can be improved by further material and geometry optimization, for instance, via selecting the proper FE material with the low-permittivity and high-DW energy (expressed through the factor ν), while the DE layer is to be done as thin as possible and should have the highest permittivity available. At the same time, the nanodot radius should be chosen as small as possible, bearing in mind the intertwined relationships between the parameters (that e.g., 2R > df, ξ0 should hold). Further improvement can be achieved by going into the nonlinear regimes near instability reversal points in the Vout(Vin) dependencies, i.e., to the parts corresponding to the flattering of P(E) curves in Fig. 2b. There, the respective values of the differential body factor, m = (dVout/dVin)−1, become appreciably smaller, as shown in the inset to Fig. 3c.

Note that if the nanodot radius is sufficiently small, the nanodot can host three locally stable states at Uin = 0, the two-domain state and two monodomain states with up- and down-oriented polarizations respectively. In this case, the described circuit implements the multivalued logic unit proposed in31, 32 where the measurement of Uout realizes the nondestructive read-out operation.

Methods

The description of the uniaxially-strained perovskite FE platelet, rests on the minimization of the functional,

where i, j = x, y, z, the uniform electric field is produced by the electrode- and depolarization surface charges, \(E = - \left( {Q{\mathrm{/}}S + \overline P _z} \right){\mathrm{/}}\varepsilon _0\varepsilon _{\mathrm{b}}\), the bar denotes averaging of the polarization at the platelet surface and εb ≃ 10 is the background contribution from core electrons to the DE response of the FE33. The uniform Ginzburg–Landau part of the functional, fGL, is taken in the strain-renormalized form with the appropriate for the PbTiO3 material coefficients34 and the compressive strain um ≃ −0.013 is produced by the SrTiO3 substrate. The gradient part of the functional, fgrad, is taken from35 with the PbTiO3-specific coefficients.

Numerical phase-field calculations were performed using the FERRET package36 for the open-source multiphysics object-oriented finite-element framework MOOSE37 by solving time-dependent relaxation equation −γ∂Pi/∂t = δF/δPi with free boundary conditions for Pi at the sample surface, coupled with electrostatic equations. Random small distribution of Pi was chosen as initial condition.

Data availability

Reprints and permissions information are available online at www.nature.com/reprints. Computational scripts are available online at https://github.com/ferroelectrics/negativec.

References

Landauer, R. Can capacitance be negative? Collect. Phenom. 2, 167–170 (1976).

Verman, L. C. Negative circuit constants. Proc. Inst. Radio Eng. 19, 676–681 (1931).

Behr, L. & Tarpley, R. Design of resistors for precise high-frequency measurements. Proc. Inst. Radio Eng. 20, 1101–1113 (1932).

Terman, F. E. Variable reactance circuit (1934). US Patent 1,950,759.

Salahuddin, S. & Datta, S. Use of negative capacitance to provide voltage amplification for low power nanoscale devices. Nano Lett. 8, 405–410 (2008).

Khan, A. I. et al. Negative capacitance in a ferroelectric capacitor. Nat. Mater. 14, 182–186 (2015).

Catalan, G., Jiménez, D. & Gruverman, A. Ferroelectrics: negative capacitance detected. Nat. Mater. 14, 137–139 (2015).

Ng, K., Hillenius, S. J. & Gruverman, A. Transient nature of negative capacitance in ferroelectric field-effect transistors. Solid State Commun. 265, 12–14 (2017).

Hoffmann, M. et al. Ferroelectric negative capacitance domain dynamics. Journ. Appl. Phys. 123, 184101 (2018).

Ricinschi, D. et al. Analysis of ferroelectric switching in finite media as a Landau-type phase transition. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 10, 477–492 (1998).

Smith, S., Chatterjee, K. & Salahuddin, S. Multidomain phase-field modeling of negative capacitance switching transients. IEEE Trans. Electron Devices 65, 295–298 (2017).

Rusu, A., Salvatore, G. A., Jiménez, D. & Ionescu, A. M. Metal-ferroelectric-meta-oxide-semiconductor field effect transistor with sub-60mv/decade subthreshold swing and internal voltage amplification. In Electron Devices Meeting (IEDM), 2010 IEEE International, 16–3 (IEEE, San Francisco, USA, 2010).

Salvatore, G. A., Rusu, A. & Ionescu, A. M. Experimental confirmation of temperature dependent negative capacitance in ferroelectric field effect transistor. Appl. Phys. Lett. 100, 163504 (2012).

Khan, A. I. et al. Differential voltage amplification from ferroelectric negative capacitance. Appl. Phys. Lett. 111, 253501 (2017).

Jo, J. & Shin, C. Negative capacitance field effect transistor with hysteresis-free sub-60-mv/decade switching. IEEE Electron Device Lett. 37, 245–248 (2016).

Si, M. et al. Steep-slope hysteresis-free negative capacitance MoS2 transistors. Nat. Nanotechnol. 13, 24 (2018).

Kwon, D. et al. Improved subthreshold swing and short channel effect in FDSOI n-channel negative capacitance field effect transistors. IEEE Electron Device Lett. 39, 300–303 (2018).

Saeidi, A. et al. Negative capacitance field effect transistors; capacitance matching and non-hysteretic operation. In Solid-State Device Research Conference (ESSDERC), 2017 47th European, 78–81 (IEEE, Leuven, Belgium, 2017).

Saeidi, A., et al. Negative capacitance as digital and analog performance booster for complementary mos transistors. arXiv preprint arXiv:1804.09622 (2018).

Cano, A. & Jiménez, D. Multidomain ferroelectricity as a limiting factor for voltage amplification in ferroelectric field-effect transistors. Appl. Phys. Lett. 97, 10–12 (2010).

Hoffmann, M., Pešić, M., Slesazeck, S., Schroeder, U. & Mikolajick, T. On the stabilization of ferroelectric negative capacitance in nanoscale devices. Nanoscale 10, 10891–10899 (2018).

Bratkovsky, A. & Levanyuk, A. Abrupt appearance of the domain pattern and fatigue of thin ferroelectric films. Phys. Rev. Lett. 84, 3177–3180 (2000).

Streiffer, S. K. et al. Observation of nanoscale 180° stripe domains in ferroelectric pbtio3 thin films. Phys. Rev. Lett. 89, 067601 (2002).

Kornev, I., Fu, H. & Bellaiche, L. Ultrathin films of ferroelectric solid solutions under a residual depolarizing field. Phys. Rev. Lett. 93, 196104 (2004).

Stephanovich, V., Luk'yanchuk, I. & Karkut, M. Domain-enhanced interlayer coupling in ferroelectric/paraelectric superlattices. Phys. Rev. Lett. 94, 047601 (2005).

Zubko, P., Stucki, N., Lichtensteiger, C. & Triscone, J.-M. X-ray diffraction studies of 180° ferroelectric domains in PbTiO3/SrTiO3 superlattices under an applied electric field. Phys. Rev. Lett. 104, 187601 (2010).

Bratkovsky, A. & Levanyuk, A. Very large dielectric response of thin ferroelectric films with the dead layers. Phys. Rev. B 63, 132103 (2001).

Zubko, P. et al. Negative capacitance in multidomain ferroelectric superlattices. Nature 534, 524–528 (2016).

Luk'yanchuk, I., Sené, A. & Vinokur, V. M. Electrodynamics of ferroelectric films with negative capacitance. Phys. Rev. B 98, 024107 (2018).

Sluka, T., Mokry, P. & Setter, N. Static negative capacitance of a ferroelectric nano-domain nucleus. Appl. Phys. Lett. 111, 152902 (2017).

Martelli, P.-W., Mefire, S. M. & Luk'yanchuk, I. A. Multidomain switching in the ferroelectric nanodots. Europhys. Lett. 111, 50001 (2015).

Baudry, L., Lukyanchuk, I. & Vinokur, V. M. Ferroelectric symmetry-protected multibit memory cell. Sci. Rep. 7, 42196 (2017).

Hlinka, J. & Marton, P. Phenomenological model of a 90°-domain wall in BaTiO3-type ferroelectrics. Phys. Rev. B 74, 104104 (2006).

Pertsev, N., Zembilgotov, A. & Tagantsev, A. Effect of mechanical boundary conditions on phase diagrams of epitaxial ferroelectric thin films. Phys. Rev. Lett. 80, 1988 (1998).

Li, Y., Hu, S., Liu, Z. & Chen, L. Phase-field model of domain structures in ferroelectric thin films. Appl. Phys. Lett. 78, 3878–3880 (2001).

Mangeri, J. et al. Topological phase transformations and intrinsic size effects in ferroelectric nanoparticles. Nanoscale 9, 1616–1624 (2017).

Gaston, D., Newman, C., Hansen, G. & Lebrun-Grandie, D. Moose: a parallel computational framework for coupled systems of nonlinear equations. Nucl. Eng. Des. 239, 1768–1778 (2009).

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by H2020-RISE-ENGIMA action (I.L., A.S., and A.R.), by internal grant No. VnGr-07/2017-23 of Southern Federal University, Russia (A.R. and Y.T.) and by the U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Science, Basic Energy Sciences, Materials Sciences and Engineering Division (V.M.V. and partially I.L.).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

I.L., Y.T., A.S., A.R. and V.M.V. conceived the work and performed calculations. I.L. and V.M.V. wrote the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Luk’yanchuk, I., Tikhonov, Y., Sené, A. et al. Harnessing ferroelectric domains for negative capacitance. Commun Phys 2, 22 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s42005-019-0121-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s42005-019-0121-0

This article is cited by

-

Quasiperiodic circuit quantum electrodynamics

npj Quantum Information (2023)

-

Circuit quantization with time-dependent magnetic fields for realistic geometries

npj Quantum Information (2022)

-

The ferroelectric field-effect transistor with negative capacitance

npj Computational Materials (2022)

-

Observation of negative capacitance in antiferroelectric PbZrO3 Films

Nature Communications (2021)

-

Thermodynamic equilibrium theory revealing increased hysteresis in ferroelectric field-effect transistors with free charge accumulation

Communications Physics (2021)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.