Abstract

Minerals are essential ingredients of the Sustainable Development Goals, but in contrast to other natural resources, they are missing from the goals and targets. This Perspective explores why and examines the narratives that shape the role of minerals in development. We share the findings of global consultations conducted under the mandate of the United Nations Environment Assembly to strengthen international cooperation on mineral governance, and we introduce the concepts of ‘development minerals’, ‘mineral security’ and ‘mineral poverty’ to better integrate minerals into the Sustainable Development Goal agenda.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

For Earth scientists working on issues of development, it is now commonplace to begin our talks and publications by reasserting that minerals are implicit to, or embedded within, each and every one of the 17 goals and 169 targets of the United Nations (UN) Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs)1,2,3,4. And while we agree with this sentiment and have started this Perspective that way, it is also true that the SDGs were formulated without explicit reference to minerals or earth materials.

The publication of Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development5 followed a three-year process of consultation, summits and high-level political forums to define the post-2015 development agenda. The 15,000-word outcome report describes the SDGs and their constituent targets and maps in detail how humanity can achieve the “Future We Want”. Natural resources feature prominently across the report, with a strong recognition that the sustainable management of natural resources is an area of “critical importance for humanity and the planet”5. Despite this, the report does not refer to the words ‘mineral’, ‘mining’ or ‘miner’ (Table 1). Forests, fisheries, wildlife, pasture, energy, water, air and genetic resources are all referenced. Agriculture, water resource management and forest management are all described in detail. Farmers, herders, pastoralists and fishers all have a place in the agenda.

Target 2.3, for example, calls for a doubling of the incomes of small-scale farmers, pastoralists and fishers, while Target 14.b calls for small-scale artisanal fishers to have access to marine resources and markets. There is no equivalent reference to the fate of the world’s 40-million-plus artisanal and small-scale miners who also live in circumstances of poverty6.

Minerals and the “Future We Want”

How could this be? How could minerals, one of the classic elements of nature so key to human existence, not be explicitly referenced in the global goals?

In 2013 and 2014, one of the authors of this Perspective was a member of the UN Sustainable Development Solutions Network Thematic Group on the Good Governance of Extractive and Land Resources. The role of this group was to provide technical advice on the formulation of the SDGs and the post-2015 development agenda. We prepared reports describing the fundamental role of minerals and their governance in sustainable development, and we formulated draft wording for goals and targets that included minerals, mining and miners for consideration by the various committees and panels crafting the agenda7.

One reason why we believe those arguments were ultimately not persuasive is that the stories that we tell as a society about minerals, mining and miners are told in predominantly one dimension: they are stories about irresponsible mining companies running roughshod over the environment and communities, as well as irresponsible artisanal and small-scale miners fuelling conflict, clearing forest and fouling rivers. This is understandable. These stories are based in fact, and we ourselves have cited plenty of examples8,9.

Narratives (and counternarratives) play an important role in shaping sustainability transitions10. When we are identifying which are the villains and heroes of our planet’s twin crises of environmental sustainability and global poverty, minerals are almost exclusively marked villain. The role that the mining of minerals has played in, for example, the colonization of nations and the creation of environmental problems is more visible and defining than the role that minerals have and continue to play in enabling our shelter, sustenance, transport, energy and communication. Minerals, according to this narrative, are an impediment to sustainable development, with their extraction negatively impacting the achievement of the SDGs. While the extraction of minerals does have this potential, the predominance of this narrative generates enormous stigma for the sector11 and the people within it, and makes it difficult for those imagining a sustainable world to create a place in this utopia for minerals, mining and miners.

The act of extraction (mining) has long been the focus of the minerals story, in a way that the role of the resource itself (minerals) has not. Our collective global discussion about agriculture, by comparison, is as much about food as it is about farming, and we can consider the current fundamental unsustainability of global food production alongside the criticality of food security and the urgency to address malnutrition. In the same way, the intersections between mining, minerals and development, in all their complexities, are crucial to advancing sustainable development.

The neglected minerals of development

A second reason, related to the first, is that the public understanding of the minerals sector bears little resemblance to the actual minerals sector. Mostly, when we think about mining, we conjure images of big machinery and global trade. We picture gold, iron ore, copper, coal, gemstones and perhaps more recently commodities central to renewable energy transitions such as lithium and cobalt. We mainly think of big, multinational mining companies, or if we do think about small-scale mining, we think mostly about those panning for gold or fossicking for diamonds.

It is little known that metals in fact make up a minority of mineral production by volume and value12. The majority of mineral commodities are not exported, and large-scale, multinational mining companies are relatively minor players in global mineral production13. The vast majority of the minerals and materials that are mined for human use are barely noticed by society. Whether it be glass, roof tiles, bridges or roads, the public is largely unaware of the minerals that are their main ingredients.

Take the case of eggs, for example. The farming of chicken eggs, whether free-range organic or in a factory, requires the addition of limestone to feed so that chickens can consistently lay their calcite mineral shells. Limestone is also the main ingredient in toothpaste, and in fact the marble quarry in Carrara, Italy, from where Michelangelo cut his famous statue of David, sells much of its product for pharmaceutical use. There are Europeans who are literally brushing their teeth with the marble of David.

Because the public imagines the minerals sector as the large-scale mining of metal ores, which indeed are renewed slowly, it neglects to imagine that many minerals are renewed at time scales more similar to that of timber. Such minerals include halite (salt), calcite and even the apatite that we grow as our teeth.

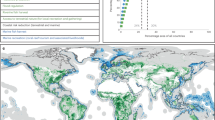

The most important mineral commodity as a function of volume and value is actually sand13,14,15,16. Estimates of global sand, gravel and crushed stone production (collectively known as aggregate) are in the vicinity of 50 billion tonnes per year, which is a staggering 6.25 tonnes per person per year, making it arguably the most utilized natural resource after water15. Most of this aggregate is crushed stone, but natural sand represents a sizable fraction, including sand sourced from rivers and the marine environment. To help visualize the scale of the sector, the total historic production of gold roughly fits into just three Olympic-sized swimming pools17. The yearly production of sand, gravel and crushed stone would not fit into ten million Olympic-sized swimming pools. And it is not just sand: eight of the top ten produced commodities are industrial (non-metallic) minerals or construction materials, which total more than 80% of global mineral production. Metals represent less than 3%13. Yet, almost all the research, policymaking and development programming on minerals and mining are about metals, energy minerals or precious stones.

Metals of course create greater societal value than their production volume would suggest, and their extraction generates large volumes of mineral waste. Nevertheless, the value and the volume of industrial minerals and construction materials are both larger and underappreciated. In the United States, for example, the value of metals production was US$33.8 billion in 2021, whereas that for industrial minerals and construction materials was US$56.6 billion. Crushed stone was the leading commodity by value at US$19.3 billion, which was almost double the value of the leading metal commodities, copper (US$11.8 billion) and gold (US$10.5 billion)12.

The narrow framing of the mining industry as exported minerals has implications not only for the way the SDGs are formulated but also for global development itself. Millions of people are involved in the mining and quarrying of local industrial minerals (such as gypsum and salt) and construction materials (such as sand, gravel, limestone and granite). And billions of people rely on these commodities for the basic ingredients of their lives.

While working at the UN Development Programme, authors of this Perspective along with colleagues13 coined the term ‘development minerals’ to describe minerals and materials that are mined, processed, manufactured and used domestically in industries such as construction, manufacturing, infrastructure and agriculture—and to recognize their positive potential. In comparison with exported mineral commodities, development minerals have closer links to local economies with more direct impacts on poverty reduction. This is not to say that mineral exports are not relevant to development, just that much of the supply chain from extraction to use is not captured locally, and the minerals (and the utility they provide) are mostly destined for consumers in developed countries. The quarrying of development minerals is dominated by informal miners and small- and medium-scale domestic businesses, and it suffers a series of environmental, social, health and safety, and labour rights challenges that are partly due to the sector’s neglect. Industrial minerals and construction materials have previously been described by economic geologists as ‘low value minerals and materials’, and while they may be low value to international commodity markets, they are fundamental from the perspective of local and domestic development.

The introduction of the term ‘development minerals’ has given more visibility to the role minerals play in poverty reduction and opened up new domains of development focus. It has inspired work on the sustainable sourcing of aggregate for infrastructure, the consideration of construction materials in disaster planning and resilience, and support to build the capacity of informal and formal small and medium-sized quarry enterprises. Development projects have included the use of local cobblestones for paving previously unsealed rural roads as a food security strategy to preserve transport routes during the wet season, support for internally displaced people from armed-conflict regions to reconstruct houses and clinics with thermally efficient soil-stabilized bricks instead of imported concrete blocks18, the introduction of low-carbon concretes made from local materials, and the use of local crushed rocks as a soil amendment for agriculture19, among many others. The term has also now been adopted in a range of national, regional and international frameworks and declarations, including those of the African Union, the UN, the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development and the World Bank.

Strengthening cooperation on minerals

There is an appetite among UN member states for greater international cooperation on the topic of mineral governance20, even in the absence of clear guidance from the SDG framework and coordinated global goals and targets related to minerals. Such cooperation builds on the UN’s role in the establishment of a range of key governance initiatives with relevance to the minerals sector and discussions that have featured across UN conferences on sustainable development21.

At the fourth session of the UN Environment Assembly (UNEA) (the principal global decision-making body on the environment), which was held in Nairobi, Kenya, on 11–15 March 2019, UN member states adopted UNEP/EA.4/Res.19 on Mineral Resource Governance22. The resolution requests the UN Environment Programme (UNEP) to collect information on sustainable practices, identify knowledge gaps and options for implementation strategies, and undertake an overview of existing assessments of different governance initiatives and approaches relating to sustainable management of metal and mineral resources.

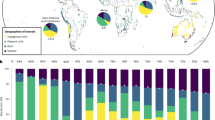

Authors of this Perspective worked with UNEP to undertake global consultations with UN member states and other stakeholders23. Twenty-three consultative meetings were held between July and November 2020, during which 1,280 people from 123 countries shared knowledge, challenges and good practice examples related to mineral resource governance. A further 111 written submissions were received from stakeholders from 61 countries (including government officials from 37 member states).

The consultations revealed a range of priority areas that found broad agreement across regions and provided the basis on which recommendations and suggested actions were presented for consideration by the UNEA (Tables 2 and 3)23,24. Summary reports capturing regional variations were published for each region25,26,27,28,29,30. The priority areas include the material intensity of recovery following the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic; platforms for cooperation and capacity building; tailings management; harmonization and alignment of governance initiatives; artisanal and small-scale mining; mine waste recycling, reuse and circularity; and national-level governance reform.

The concept of development minerals helped widen the conversation beyond the traditional domains of metals, energy minerals and precious stones. Sand sustainability featured prominently, bolstered by UNEP reports on the topic15,31.

On the basis of this work, UN member states in March 2022 adopted resolution 5/12 on ‘Environmental aspects of minerals and metals management’, which asks UNEP to convene consultations that feed into a global intergovernmental meeting, with the aim of developing proposals to enhance international cooperation and the environmental sustainability of minerals in line with the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development32.

Towards the post-2030 SDG agenda

Part of the challenge of integrating minerals into sustainable development and the framework of the SDGs is to offer clear concepts that include the totality of minerals contribution or that articulate the links to poverty reduction and human development. Earlier we introduced the concept of development minerals and how this concept can help make obvious the links between the local minerals and materials and local development, as well as bring those links to the forefront of global conversations about sustainable development.

Another feature of the public discourse on minerals, when compared with other natural resources, is that access to mineral supply is almost never discussed from a human-centred perspective. In Table 1, we identified that a major part of the framing of natural resources in the SDGs relates to their fair and affordable access for development, with explicit or implicit reference in the goals and targets to food security, energy security and water security.

The issue of access to minerals for development has so far predominantly been framed through the lens of criticality. Critical minerals refer to metallic and non-metallic elements that are essential for the economic and national security of states, especially advanced manufacturing and technology, and that are at risk of supply chain disruption or, by some measures, also have substantial environmental impacts associated with extraction33,34,35. The reference point for which criticality is defined is the state, the security being sought is mineral supply for defence and industry, and the most common elements identified as critical are rare-earth elements, platinum group metals and indium34. Businesses too have applied the concept to understand potential disruptions to their own supply chains. Critical minerals as a conceptual frame helps states (and businesses) to plan for their economic development but falls short if our concern is human-centred where access is considered from the reference point of the local availability of minerals for the basics of human development.

In the case of agriculture, academics, practitioners and policymakers have been successful at expressing the clear and unequivocal link between the availability of food and human development, defining food security first as the availability of basic foodstuffs36 and later as existing “when all people, at all times, have physical, social and economic access to sufficient, safe and nutritious food that meets their dietary needs and food preferences for an active and healthy life”37.

To amplify the links between minerals and development, here we introduce the concepts of mineral security and mineral poverty. We define mineral security to exist when all people have sufficient and affordable access to the minerals necessary for human development, including for shelter, mobility, communication, energy and sustenance. Mineral security also implies access to the beneficiation and transformation necessary to turn minerals into usable commodities. Mineral insecurity is most acutely, though not exclusively, experienced in circumstances of poverty. The lack of access to the minerals necessary for development is both a contributing factor and a consequence of poverty. We refer to mineral poverty as a state of mineral insecurity associated with poverty. Mineral poverty may limit access to vital infrastructure and services such as housing, transport and energy, and is interconnected with the other material dimensions of poverty.

Mineral security and mineral poverty are not terms that are currently in wide use. A literature search revealed the phrase ‘mineral security’ in just 10 publications, compared with 46,535 for food security (Web of Science; 25 May 2022), with few prior definitions of the term. In all prior uses, and like the term ‘critical minerals’, mineral security has been used in the context of a state’s quest to secure critical supplies for defence and industry38,39,40. A literature search for the phrase ‘mineral poverty’ revealed no results (Web of Science; 25 May 2022).

Assessments of mineral security, especially in the context of mineral poverty, might be usefully conducted at multiple scales and integrated into the national development planning process or into baseline assessments for development programming. Assessments might cover a wide range of issues (Box 1).

As is clear from Box 1, there are strong interlinkages between food, energy, water and mineral security that are worthy of greater investigation, even more than what has already been mapped by those exploring the relationships between mining and the existing SDG framework1,2,3,16. Aided by the concepts of development minerals, mineral security and mineral poverty, we believe that new understandings about development, new actors and new pathways for sustainability transitions can be identified, and alternative narratives will ultimately emerge to better communicate the essential role of minerals.

Ahead of us now lies the task of utilizing these new concepts in such a way that minerals are a more central feature of the post-2030 development agenda and any revised formulation of the SDGs. We will not pre-empt here the formulation that UN member states should settle on, whether it be the inclusion of a stand-alone goal or one that is integrated with other natural resources. However, we advocate taking advantage of the opportunity to build consensus during the implementation of the UNEA 5/12 resolution to activate these new concepts and build on the innovations in practice that they may usher in. Minerals and mining have enormous capacity to both enable and undermine the achievement of the SDGs. Our task is to make clear why minerals are worthy of inclusion in the “Future We Want”.

References

Mapping Mining to the Sustainable Development Goals: An Atlas (Columbia Center on Sustainable Investment, United Nations Development Programme and World Economic Forum, 2016).

de Haan, J., Dales, K. & McQuilken, J. Mapping Artisanal and Small-Scale Mining to the Sustainable Development Goals (Univ. Delaware and PACT, 2020).

Mancini, L. et al. Mapping the Role of Raw Materials in Sustainable Development Goals: A Preliminary Analysis of Links, Monitoring Indicators, and Related Policy Initiatives (Joint Research Centre, European Commission, 2019); https://doi.org/10.2760/026725

Ayuk, E. T. et al. Mineral Resource Governance in the 21st Century: Gearing Extractive Industries Towards Sustainable Development International Resource Panel (United Nations Environment Programme, 2020).

Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development A/RES/70/1 (United Nations, 2015).

2020 State of the Artisanal and Small-Scale Mining Sector (World Bank, 2020).

Harnessing Natural Resources for Sustainable Development: Challenges and Solutions Technical Report for the Post-2015 Development Agenda (United Nations Sustainable Development Solutions Network, 2013).

Franks, D. M. et al. Conflict translates environmental and social risk into business costs. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 111, 7576–7581 (2014).

Franks, D. M. Mountain Movers: Mining, Sustainability and the Agents of Change (Earthscan, 2015).

Wyborn, C. et al. Imagining transformative biodiversity futures. Nat. Sustain. 3, 670–672 (2020).

Franks, D. M., Ngonze, C., Pakoun, L. & Hailu, D. Voices of artisanal and small-scale mining, visions of the future: report from the International Conference on Artisanal and Small-Scale Mining and Quarrying. Extr. Ind. Soc. 7, 505–511 (2020).

Mineral Commodity Summaries 2022 (US Geological Survey, 2022); https://doi.org/10.3133/mcs2022

Franks, D. M. Reclaiming the neglected minerals of development. Extr. Ind. Soc. 7, 453–460 (2020).

Bendixen, M., Best, J., Hackney, C. & Iversen, L. L. Time is running out for sand. Nature 571, 29–31 (2019).

Sand and Sustainability: 10 Strategic Recommendations to Avert a Crisis (GRID-Geneva, United Nations Environment Programme, 2022).

Bendixen, M. et al. Sand, gravel, and UN Sustainable Development Goals: conflicts, synergies, and pathways forward. One Earth 4, 1095–1111 (2021).

How Much Gold Has Been Mined? (World Gold Council, 2017); https://www.gold.org/about-gold/gold-supply/gold-mining/how-much-gold-has-been-mined

Junior, P., Franks, D. M. & Arbeláez-Ruiz, D. Minerals as a refuge from conflict: evidence from the quarry sector in Africa. J. Rural Stud. 92, 206–213 (2022).

Manning, D. A. C. & Theodoro, S. H. Enabling food security through use of local rocks and minerals. Extr. Ind. Soc. 7, 480–487 (2020).

Ali, S. H. et al. Mineral supply for sustainable development requires resource governance. Nature 543, 367–372 (2017).

United Nations General Assembly Resolution Adopted by the General Assembly on 27 July 2012: The Future We Want A/RES/66/288 (United Nations, 2012).

United Nations Environment Assembly Mineral Resource Governance 4/19 UNEP/EA.4/Res.19 (United Nations Environment Programme, 2019).

Mineral Resource Governance and the Global Goals: An Agenda for International Collaboration—Report of Activities to Implement United Nations Environment Assembly Resolution on Mineral Resource Governance (UNEP/EA.4/Res.19) (United Nations Environment Programme and Univ. Queensland, 2022).

United Nations Environment Assembly Progress in the Implementation of Resolution 4/19 on Mineral Resource Governance: Report of the Executive Director UNEP/EA.5/14 (United Nations Environment Programme, 2020).

Implementing UNEA Resolution 4/19 on Mineral Resource Governance: Regional Summary West Asia (United Nations Environment Programme and Univ. Queensland, 2020).

Implementing UNEA Resolution 4/19 on Mineral Resource Governance: Regional Summary Asia Pacific (United Nations Environment Programme and Univ. Queensland, 2020).

Implementing UNEA Resolution 4/19 on Mineral Resource Governance: Regional Summary Africa (United Nations Environment Programme and Univ. Queensland, 2020).

Implementing UNEA Resolution 4/19 on Mineral Resource Governance: Regional Summary North America (United Nations Environment Programme and Univ. Queensland, 2020).

Implementing UNEA Resolution 4/19 on Mineral Resource Governance: Regional Summary Latin America and the Caribbean (United Nations Environment Programme and Univ. Queensland, 2020).

Implementing UNEA Resolution 4/19 on Mineral Resource Governance: Regional Summary Europe and Caucasus (United Nations Environment Programme and Univ. Queensland, 2020).

Sand and Sustainability: Finding New Solutions for Environmental Governance of Global Sand Resources (United Nations Environment Programme, 2019).

United Nations Environment Assembly Environmental Aspects of Minerals and Metals Management 5/12 UNEP/EA.5/Res.12 (United Nations Environment Programme, 2022).

Nassar, N. T. & Fortier, S. M. Methodology and Technical Input for the 2021 Review and Revision of the U.S. Critical Minerals List Open-File Report 2021–1045 (US Geological Survey, 2021); https://doi.org/10.3133/ofr20211045

Hayes, S. M. & McCullough, E. Critical minerals: a review of elemental trends in comprehensive criticality studies. Resour. Policy 59, 192–199 (2018).

Graedel, T. E., Reck, B. K. & Miatto, A. Alloy information helps prioritize material criticality lists. Nat. Commun. 13, 150 (2022).

Report of the World Food Conference, Rome, 5–16 November 1974 E/Conf/65/20 (United Nations, 1975).

The State of Food Insecurity in the World 2001 (Food and Agriculture Organization, 2002).

Szamałek, K. et al. The role of mineral resources knowledge in the economic planning and development in Poland. Resour. Policy 74, 102354 (2021).

Ray, G. F. Mineral reserves: projected lifetimes and security of supply. Resour. Policy 10, 75–80 (1984).

Zhang, L. et al. Critical mineral security in China: an evaluation based on hybrid MCDM methods. Sustainability 10, 4114 (2018).

Beerling, D. J., Kantzas, E. P. & Lomas, M. R. Potential for large-scale CO2 removal via enhanced rock weathering with croplands. Nature 538, 242–248 (2020).

Acknowledgements

We thank all individuals and organizations that generously contributed their expertise, time and energy towards the consultations on mineral resource governance conducted under the mandate of the UNEA. In particular, we acknowledge E. Tonda, A. Kariuki, C. Ndakorerwa, G. Lloyd, F. Gaetani, R. Wabunoha, T. Alkhoury, P. Mwesigye, F. Ndoye and R. Tsutsumi (UNEP); and L. Platchkov and M. Rohn (Federal Office of the Environment of the Government of Switzerland). N. Plint and D. Kemp (University of Queensland), L. Noronha (UNEP), and L. Gallagher (University of Geneva) reviewed earlier drafts. Funding was provided by the Federal Office of the Environment of the Government of Switzerland to conduct global consultations in support of the implementation of the UNEA Mineral Resource Governance resolution 4/19.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

D.M.F., J.K. and D.H. conceptualized the paper, performed the analysis, wrote the original draft, and reviewed and edited the paper. D.M.F. and J.K. worked with UNEP to convene global consultations on mineral resource governance.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Sustainability thanks Jocelyn Fraser and Tim Werner for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Franks, D.M., Keenan, J. & Hailu, D. Mineral security essential to achieving the Sustainable Development Goals. Nat Sustain 6, 21–27 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41893-022-00967-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41893-022-00967-9